Abstract

Lunar mare basalts illuminate the nature of the Moon’s mantle, the lunar compositional asymmetry and the early lunar magma ocean (LMO)1,2,3. However, the characteristics of the mantle beneath the vast South Pole–Aitken (SPA) basin on the lunar farside remain a mystery. Here we present the petrology and geochemistry of basalt fragments from Chang’e-6 (CE6), the first returned lunar farside samples from the SPA basin4,5,6,7. These 2.8-billion-year-old CE6 basalts8 share similar major element compositions with the most evolved Apollo 12 ilmenite basalts. They exhibit extreme Sr–Nd depletion, with initial 87Sr/86Sr ratios of 0.699237 to 0.699329 and εNd(t) values (a measure of the neodymium isotopic composition) of 15.80 to 16.13. These characteristics indicate an ultra-depleted mantle, resulting from LMO crystallization and/or later depletion by melt extraction. The former scenario implies that the nearside and farside may possess an isotopically analogous depleted mantle endmember. The latter is probably related to the SPA impact, indicating that post-accretion massive impacts could have potentially triggered large-scale melt extraction of the underlying mantle. Either way, originating during the LMO or later melt extraction, the ultra-depleted mantle beneath the SPA basin offers a deep observational window into early lunar crust–mantle differentiation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Orbital observations have identified notable differences in crustal thickness, magmatic activity and geochemical compositions between the nearside and farside of the Moon9,10,11,12. However, the origin of this collective evidence of a lunar asymmetry remains debated. A number of hypotheses have been proposed, including asymmetrical crystallization of the lunar magma ocean (LMO)13,14, asymmetrical mantle convection15,16 or large impacts on the nearside17 or on the farside18,19. One of the key objectives in testing this wide range of hypotheses is to ascertain whether the lunar asymmetry formed during LMO solidification or resulted from subsequent processes. Comparative studies of the deep lunar mantle20 on the nearside and farside have the potential to provide constraints on this issue. However, all sample-return missions to date, from Apollo 11 to Chang’e-5 (CE5), collected samples exclusively from the lunar nearside. Thus, the characteristics of the lunar farside mantle remain unknown because of the lack of farside samples collected.

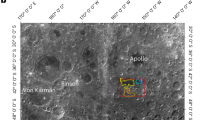

On 25 June 2024, China’s Chang’e-6 (CE6) mission successfully returned the first lunar farside samples from the South Pole–Aitken (SPA) basin (Fig. 1). The landing site of the CE6 probe was situated on a mare basalt unit (153.9856° W, 41.6383° S)4,5,6,7,21. The samples provide an opportunity to investigate the composition and nature of the farside lunar mantle. In this study, we present a petrological and geochemical study of 16 CE6 basalt fragments picked from two scooped soil subsamples. The findings offer a crucial foundation for revealing the nature of the LMO and the origin of the lunar asymmetry.

a, TiO2 map for mare basalt in the SPA basin. The Apollo basin, Von Kármán and Leibnitz craters and basaltic plains of Mare Ingenii are also shown. The red box delineates the area depicted in b. b, Regional TiO2 map for the mare basalt of the CE6 landing site (red triangle). The base map is the Chang’e-1 lunar global image mosaic37. The distribution of mare basalts and TiO2 abundances are from refs. 9,38.

The 16 basalt fragments studied here (around 0.5–6 mm in size) exhibit a range of textures, including porphyritic, subophitic and poikilitic (Extended Data Fig. 1). Four of the fragments are of sufficient mass (more than 30 mg) to permit high-precision whole-rock major and trace element and Sr–Nd isotope analyses, as well as petrological observation (Extended Data Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 1). The CE6 basalt fragments are composed of clinopyroxene, plagioclase and ilmenite, as well as minor amounts of silica, olivine (mostly fayalite), ulvöspinel, troilite, Ca-phosphates and Zr-bearing minerals. The mineral modes were estimated to be 46–70 vol.% clinopyroxene and 22–50 vol.% plagioclase, with ilmenite comprising less than 7 vol.% (Supplementary Table 2). Ilmenite crosscuts both the clinopyroxene and plagioclase, and occurs as a late-stage crystallization phase, indicating a low-Ti basalt crystallization sequence22 (Extended Data Fig. 1). Forsterite is rare in the studied CE6 basalt fragments, with the exception of one grain found in fragment YJFM002-013 (Extended Data Fig. 1b). Various mineral phases in 15 of the 16 fragments were dated through in situ Pb–Pb geochronology, yielding a consistent crystallization age of 2.807 ± 0.003 billion years ago (Ga)8.

The mineral chemistries of the CE6 basalt fragments indicate a cooling crystallization of the lava, similar to the approximately 2.0-billion-year-old CE5 basalt23, as evidenced by the pronounced Fe enrichment (Supplementary Table 3). The clinopyroxene compositions indicate crystallization temperatures ranging from 1,200 down to 800 °C (Extended Data Fig. 3a). On a Ti# (atomic Ti/(Ti + Cr)) versus Mg# (atomic Mg/(Mg + Fe)) plot, the data for the pyroxene follow a crystallization trend typically observed in the low-Ti mare basalts (Extended Data Fig. 3b). The plagioclase grains show considerable variations in anorthite (An) content, ranging from An81 to An94 (Extended Data Fig. 3c). The cores of the olivine grains have a Mg# of 66–58, which is more ferroan than the earliest-crystallizing olivine in the Apollo mare basalts (Extended Data Fig. 3d).

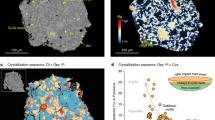

The bulk compositions of the CE6 basalt fragments exhibit contents of TiO2 (3.5–5 wt%), Al2O3 (10–11 wt%) and K2O (0.08–0.11 wt%) consistent with those of low-Ti/low-Al/low-K-type mare basalts (Extended Data Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 4). In comparison to the Apollo 12 and 15 low-Ti basalts, they show elevated FeO (21–23 wt%) and a low Mg# (30–36). The bulk trace element concentrations, except for Rb, K and P, of the CE6 basalts vary from 30–50 times those of carbonaceous chondrites, thus being much lower than those of the CE5 basalt (Extended Data Fig. 5a). The rare earth elements (REEs) exhibit middle-REE-enriched patterns with a slight negative Eu anomaly ([Eu/Eu*]cn = 0.7–0.8) and a steep heavy-REE trend (Sm/Yb ratios = 1.7–1.9). This REE pattern is similar to those of the Apollo 15 basalts (such as sample 15545), despite the CE6 basalt fragments having overall higher REE concentrations (Extended Data Fig. 5b). The Sr–Nd isotope analyses yielded low initial 87Sr/86Sr ratios of 0.699237 to 0.699329 and extremely high εNd(t) values of 15.80 to 16.13 (Supplementary Table 5). εNd(t) = ((143Nd/144Nd)sample(t)/(143Nd/144Nd)CHUR − 1) × 10,000, where (143Nd/144Nd)sample(t) and (143Nd/144Nd)CHUR are the Nd isotopic compositions of the sample and the chondritic uniform reservoir (CHUR) at t = 2.807 Ga, respectively. The calculated 87Rb/86Sr and 147Sm/144Nd for the mantle source are 0.008–0.011 and 0.262–0.272, respectively, making the CE6 basalt among the most depleted of all reported mare basalts (Fig. 2).

a, The 87Rb/86Sr ratios of the CE6 basalt source regions were calculated assuming a single-stage model in which the Moon differentiated at 4.56 Ga, with an initial 87Sr/86Sr ratio of 0.69903 (refs. 39,40). The bulk Moon 87Rb/86Sr value is from refs. 39,41. b, The 147Sm/144Nd ratios of the CE6 basalt source regions were calculated assuming a two-stage growth model following refs. 42,43. In this model, the Moon followed a chondritic path until differentiation occurred at 4.42 ± 0.07 Ga, represented by the model age of urKREEP formation44,45. The Sr and Nd isotopic data from the CE6 basalts were acquired from whole-rock Rb–Sr and Sm–Nd analyses (Supplementary Table 5 and Methods). The initial 87Sr/86Sr and εNd(t) values were calculated using a rock formation age of 2.807 Ga (ref. 8). The horizontal solid lines in a and b refer to the primordial reservoir. The Apollo mare basalt and meteorite data (including samples 12051 and northwest Africa (NWA) 773) are from ref. 43 and references therein. The CE5 basalt data are from ref. 23. The depleted Nd isotopic compositions of the CE6 basalt source could have been produced by either: (1) inheritance from a depleted primordial mantle; and/or (2) later depletion by melt extraction. BABI, basaltic achondrite best initial.

Origin of the CE6 basalt

The 16 studied CE6 basalt fragments exhibit an identical age8, comparable mineral chemistries and homogeneous Sr–Nd isotopic compositions, collectively suggesting that they share a similar petrogenesis. However, because of the small sizes of these basalt fragments, their whole-rock major and trace element compositions may have been affected by non-model sampling. Among the four fragments characterized for their bulk geochemical signatures, the fragment YJYX251 exhibits a higher Mg# (36) and lower REE concentrations (Extended Data Fig. 5b). The highest Mg# of clinopyroxene in this fragment is 62 (Supplementary Table 3), which should have precipitated from an equilibrium melt with a low Mg# of 26 when the Mg–Fe partition coefficient is 0.22 (ref. 24). This discrepancy indicates the non-model sampling of Mg-rich clinopyroxene in this fragment. Conversely, the most Mg-rich clinopyroxenes (Mg# = 64–66) in the other three fragments are thought to have precipitated from equilibrium melts with a Mg# of 28–30, consistent with their whole-rock Mg# of 29–31. Therefore, these three fragments are considered to represent the composition of the basalt at the CE6 landing site. They show major element signatures similar to those of the most evolved Apollo 12 ilmenite basalt (12051) (Extended Data Fig. 4). In addition, the CE6 basalt and 12051 fall on a similar Sm–Nd evolutionary trend (Fig. 2b), suggesting that their mantle sources had nearly the same Sm/Nd ratio. It can therefore be posited that the CE6 basalt and the Apollo 12 ilmenite basalt may have originated from mantle sources with similar compositional characteristics.

However, compared to the Apollo 12 ilmenite basalt, the CE6 basalt has a middle-REE enrichment pattern with a steep heavy-REE trend (Extended Data Fig. 5b), indicating slight compositional differences between the mantle sources of these two basalt groups. To elucidate the mechanism responsible for this difference, a trace element modelling approach previously employed for the Apollo basalts25 was employed for the CE6 basalt. Four LMO models26,27,28,29 with initial magma ocean depths from 600 km to fully molten were selected. The slight negative Eu anomaly in the CE6 basalt indicates that its mantle source underwent only a minor degree of plagioclase separation during LMO crystallization. Accordingly, the earliest LMO cumulates that underwent plagioclase separation in each model were taken as the source of the CE6 basalt. Small amounts (0.3–1.0%) of trapped instantaneous residual liquid (TIRL) were added to reproduce the measured source 147Sm/144Nd ratio of 0.262–0.272. The results indicate that the partial melting of these mantle sources is unable to reproduce the REE composition of the CE6 basalt, particularly its steep heavy-REE trend (Extended Data Fig. 6).

Two potential explanations are proposed for the steep heavy-REE pattern observed in the CE6 basalt. One is that garnet was retained in the mantle residue. This mechanism has previously been considered as an explanation for the elevated Sm/Yb ratios of the Apollo 17 green volcanic glasses30 and Apollo 15 basalts25. If 0.8% garnet is retained in the mantle source, then the steep heavy-REE patterns observed in Apollo 15 basalt 15545 and the CE6 basalt can be successfully reproduced (Fig. 3a and Extended Data Fig. 7a). In this scenario, a small degree (1–1.5%) of partial melting with moderate (32–45%) fractional crystallization is required to produce Apollo 15 basalt 15445, with more extensive (66–75%) fractional crystallization needed to generate the CE6 basalt. This result is consistent with the higher Mg# value and lower Al2O3, TiO2 and CaO contents of 15545 than those of the CE6 basalt (Extended Data Fig. 4), indicating that the CE6 basalt may have been formed by the fractional crystallization of a melt with a REE composition similar to the Apollo 15 basalt. Although a possible explanation30 to be considered further, in light of the CE6 REE pattern, lunar garnet has fallen out of favour because it cannot directly crystallize from various LMO models26,27,28 and the experimental study did not support its presence in the mare basalt sources31.

a, REE modelling of deviation from a garnet-bearing mantle source. The mantle source was assumed to be 78 PCS cumulate + 0.6% TIRL from the LMO model from ref. 29, with 0.8% garnet in the residue. A small degree (1–1.5%) of partial melting with moderate (32–45%) fractional crystallization is required to produce the Apollo 15 basalt 15445, with more extensive (66–75%) fractional crystallization needed to generate the CE6 basalt. b, REE modelling of the deviation from a high-Sm/Yb mantle source. The mantle source was assumed to be 78 PCS cumulate from the LMO model of ref. 27 with a contribution of 0.8% high-Ti component, which is represented by an Apollo 11 high-Ti basalt (10050) from ref. 25. A small degree (0.7–1.0%) of partial melting with moderate (0–40%) fractional crystallization can reproduce the REE pattern of the CE6 basalt. The normalization values are from ref. 46. Because the CE6 basalts may have a similar source to the Apollo 12 basalts, we adopted the modal mineralogy calculated for the Apollo 12 basalts (52% olivine, 23% orthopyroxene, 23% pigeonite, 2% augite)25. The model parameters are listed in Supplementary Tables 6 and 7, and details of the batch melting and fractional crystallization model are provided in the Methods. The REE abundances of the CE6 basalt are the average composition of the three fragments CE6C0000YJYX48501, CE6C0000YJYX48901 and CE6C0000YJYX56201. The error bars are 1 s.d. CI chondrite, Ivuna-type carbonaceous chondrite.

An alternative possibility is that the CE6 mantle source itself had a high Sm/Yb ratio. Given that the mantle source also exhibits depletion in light REEs with a high Sm/Nd ratio constrained by the Nd isotopes, it would necessitate the incorporation of a middle-REE enriched material into the mantle. One potential source for this material could be the high-Ti component associated with ilmenite-bearing later-stage LMO cumulates. A contribution of this high-Ti component would result in the formation of a high-Sm/Yb-ratio mantle source (Extended Data Fig. 7b). A small degree (0.7–1.0%) of partial melting of this high-Sm/Yb-ratio source with moderate (0–40%) fractional crystallization could reproduce the REE composition of the CE6 basalt (Fig. 3b). This result is also consistent with the relatively higher TiO2 contents of CE6 in comparison to the Apollo low-Ti basalts (Extended Data Fig. 4). If this is the case, it could indicate that mantle overturn15,16 might have occurred in the SPA basin, with ilmenite-bearing later-stage LMO cumulates sinking deep. It should be noted, however, that other mechanisms to form a high-Sm/Yb-ratio mantle source are also conceivable.

Ultra-depleted mantle of the farside SPA basin

The extremely depleted Sr–Nd isotopic compositions indicate that the CE6 basalt originated from an ultra-depleted mantle. The formation of this ultra-depleted mantle beneath the SPA basin could have been controlled by two potential processes: (1) inheritance from a depleted mantle that crystallized from the LMO; and/or (2) later depletion by melt extraction (Fig. 2b).

If the CE6 basalt originated from a deep lunar mantle source that was unaffected by melt extraction, then the depleted characteristics would have presumably formed during LMO crystallization. The isotope systematics of lunar nearside samples have indicated the presence of three major reservoirs in the Moon, including a deep mantle source, a shallow mantle source and the concept of primeval KREEP (the proposed last dreg of LMO which is enriched in K, REEs and P), with the vast majority of lunar samples able to be modelled by the mixing of these three reservoirs32. The deep mantle source with extremely positive εNd values32 is represented by the Apollo 12 ilmenite basalts and their derivation from 350–400 km depth33. The mantle source of the CE6 basalt falls along the same Sm–Nd evolutionary trend as that of the most depleted Apollo 12 ilmenite basalt (12051) (Fig. 2b), and both basalts have similar major elemental compositions (Extended Data Fig. 4), indicating that the most depleted mantle endmembers of the nearside and farside share some petrological and geochemical similarities. This potential hemispheric consistency implies that the nearside and farside could be symmetrical, at least during the LMO crystallization of these mantle sources. The observed asymmetry, including crustal thickness, magmatic activity and geochemical compositions, would then probably be the result of later processes.

Otherwise, the CE6 basalt may have originated from a relatively shallow mantle source that was affected by melt extraction (Fig. 2b). Such melt extraction could have been caused by either the SPA impact or later volcanism. The occurrence of such an event would be expected to be early because it would require time for the mantle to evolve to the highly depleted isotopic compositions at around 2.8 Ga. Compared to the earliest volcanism in the Apollo basin at around 3.4 Ga (ref. 5), melt extraction induced by the SPA impact (around 4.33 Ga from ref. 34) is a more reasonable scenario. The SPA impact that formed an approximately 2,000-km crater could have potentially triggered extensive melt extraction from the underlying mantle (Fig. 4). Simulations of the SPA impact suggest that melting at depths of less than 250 km in the upper mantle may have occurred27,28. This process would not only result in the depletion of incompatible trace elements, as observed in the CE6 mantle source, but also a loss of volatile elements and the fractionation of volatile isotopes, which can be verified by further study of the CE6 basalt. Such impact-related melt extraction would imply that similar post-accretion massive impacts with diameters of more than 1,000 km found throughout the Solar System35 may have played an underappreciated and poorly constrained role in contributing to the early crust–mantle differentiation of terrestrial bodies by impact-induced melting of the upper mantle36. Whether vestigial from LMO crystallization or later depletion by melt extraction, the ultra-depleted mantle beneath the SPA basin informs early lunar crust–mantle evolution.

a, Formation of the SPA basin at around 4.33 Ga (ref. 34). Hydrocode models suggest that the upper approximately 250 km of the lunar interior was melted47 and that melts gathered at the bottom of the SPA basin to form an approximately 50-km-thick melt sheet after impact47,48. However, the heating effect of the SPA impact on the underlying mantle remains poorly understood. The dashed lines represent the isotherms of the lunar mantle based on constraints from ref. 48. b, Eruption of the CE6 basalt at around 2.8 Ga (ref. 8). The rheological barrier refers to the base of the lithosphere. Removal of the thermally insulating megaregolith/crust in the SPA basin could have resulted in a faster cooling rate and a deeper rheological barrier49. The mantle source of the CE6 basalt may have undergone melt extraction or it may have remained unaffected.

Methods

Sample preparation

The studied CE6 samples (CE6C0100YJFM001, about 5,000 mg, and CE6C0100YJFM002, about 2,000 mg) were allocated by the China National Space Administration. Both samples were scooped from the lunar surface. A total of 16 basalt fragments were picked out from the soil samples for detailed petrological and geochemical analysis (Supplementary Table 1). Four large fragments (CE6C0000YJYX25101, CE6C0000YJYX48501, CE6C0000YJYX48901 and CE6C0000YJYX56201) had sufficient mass (more than 30 mg) for whole-rock major, trace and Sr–Nd isotope analyses to be performed. Thus, each of the four fragments was cut into two parts, one for scanning electron microscope (SEM) analysis and electron probe microanalysis (EPMA), and the other for whole-rock major, trace and Sr–Nd isotope analysis. The remaining 12 smaller fragments were only examined by SEM and EPMA. Before the SEM analysis and EPMA, the samples were embedded in 1-in. epoxy mounts and polished.

SEM analysis and energy dispersive spectrometer mapping

The petrography was carried out on a Zeiss Supra 55 field-emission SEM at the Key Laboratory of Lunar and Deep Space Exploration, National Astronomical Observatories, Chinese Academy of Sciences and a Zeiss Gemini 450 field-emission SEM at the Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IGGCAS) in Beijing, China. The accelerating voltage was 15.0 kV and the probe current was 2.0 nA. In addition, a Thermo Scientific Apreo SEM equipped with an energy dispersive spectrometer was used at IGGCAS to obtain the modal abundance of each mineral and calculate the bulk major element compositions based on the elemental mapping. The results are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Electron microprobe analysis of minerals

The major element concentrations of pyroxene, plagioclase, olivine, ilmenite, spinel, quartz, sulfide and phosphates in each sample were analysed using a JEOL JXA8230 electron probe at the National Astronomical Observatories, Chinese Academy of Sciences, and a JEOL JXA8100 electron probe at the IGGCAS. The conditions of the EPMA were as follows: accelerating voltage of 15 kV, probe current of 20 nA, focused beam and peak counting time of 10 s. Calibration of the elemental data was done using a series of natural minerals and synthetic materials. The analytical crystals and calibration standards were as follows: Na (thallium acid phthalate, natural albite), Mg (thallium acid phthalate, natural diopside), Al (thallium acid phthalate, synthetic Al2O3), Si (thallium acid phthalate, natural diopside), Cr (lithium fluoride, synthetic Cr2O3), Mn (lithium fluoride, natural bustamite), Fe (lithium fluoride, haematite), Ni (lithium fluoride, synthetic NiO), K (pentaerythritol, natural K-feldspar), Ca (pentaerythritol, natural diopside) and Ti (pentaerythritol, synthetic rutile). Based on an analysis of the internal laboratory standards, the precision for the major (more than 1.0 wt%) and minor (0.1–1.0 wt%) elements were better than 1.5 and 5.0%, respectively. The analytical data from the samples and standards are listed in Supplementary Table 3.

Whole-rock major and trace elements

Aliquots of 30 mg of each of the four samples analysed for bulk chemistry were mixed thoroughly with ultrapure lithium borate (3.0 g) in a Pt–Au crucible at a ratio of 1:100. The sample was then melted at 1,050 °C using an M4 propane gas automatic fluxer before being cast into a 27-mm-disk-shaped glass sample. The prepared disc-shaped glass sample was measured using panalytical wavelength-dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectrometry. The X-ray fluorescence spectra were calibrated after measuring the intensities of 44 international reference materials. The criteria for selecting these samples were based on the required concentration intervals. The instrument conditions were consistent with those reported in ref. 50.

The trace elements were subsequently analysed using laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry on lithium borate glass discs, employing an Agilent 8900 ICP-MS instrument coupled with a high-repetition-rate Genesis GEO Femtolaser Ablation System51. Ablation was performed using spots with a diameter of 100 µm and a length of 1,000 µm, at a frequency of 1 Hz for 45 s, following a 25-s measurement of the gas blank. A 25-s washout between analyses was used. The gas flows were optimized by spot ablation of the National Institute of Standards and Technology Standard Reference Material (NIST SRM) 612 glass standard reference material to obtain maximum signal intensities while maintaining the ThO/Th ratio below 0.3% and the U/Th ratio at 0.95–1.05. During the test, Al was used as the internal standard, while NIST SRM 612 served as the external standard for sample measurement.

For the major elements, the deviations between the analytical results and the reference values range from 0.5 to 1.5%, depending on the mass fractions of the elements, while the relative standard deviation was maintained within 2%. For trace elements, the measurement bias between the analytical results and the reference values was within 10%, and the relative standard deviation was maintained within 10%. The analytical data of the samples and standards are listed in Supplementary Table 4.

Whole-rock Rb–Sr and Sm–Nd isotopes

All chemical procedures, including sample dissolution and the chromatographic separations, were conducted on and in International Organization for Standardization (ISO) class 5 clean benches or hoods in an ISO class 6 ultra-clean laboratory. Approximately 3–5 mg of CE6 basalt fragments, along with appropriate amounts of 87Rb–84Sr and 149Sm–150Nd spikes, were weighed into 2-ml Savillex perfluoro alkoxy polymer beakers. The samples were dissolved in tightly capped perfluoro alkoxy polymer vials using 0.5 ml of HF and 0.1 ml of HNO3 at 150 °C on a hotplate for 1 day, with intermittent sonication for 1 h to enhance the dissolution. The solutions were then evaporated to dryness and redissolved in 0.2 ml of 1.5 M HCl and 0.1 M HF to obtain a clear solution with no visible residue.

The sample solutions were first loaded into pre-cleaned homemade columns packed with approximately 0.25 ml of AG 50W-X12 200–400-mesh resin to separate the matrix elements Rb, Sr and the REEs. The columns were pre-cleaned using three washes of 3 ml of 6 M HCl, followed by 1 ml of Milli-Q water, and then were equilibrated with 1 ml of 1.5 M HCl and 0.1 M HF. After loading the sample, the major matrix elements and the trace elements, such as U, Pb and Hf, were eluted with four washes of 0.25 ml of 1.5 M HCl and 0.1 M HF. Additional major matrix elements (Fe, Mg and K) were washed out with 1 ml of 1.5 M HCl. After that, Rb was stripped using 1.5 ml of 1.5 M HCl. Subsequently, Sr, Ca, Ba and the REEs were recovered using 5 ml of 6 M HCl.

In the second step, Bio-Rad Bio-Spin columns packed with 0.5 ml of Sr spec resin were used to separate the Sr and REEs. The resin columns were pre-washed using three 2-ml washes of Milli-Q water and conditioned with 2 ml of 3 M HNO3. The Sr–REE solutions from the first column were evaporated to dryness, redissolved in 0.2 ml of 3 M HNO3 and then loaded into the columns. The REEs were collected with the sample load and further recovered by washing with 0.5 ml of 3 M HNO3 three times. After three rounds of washing with 2 ml of 7 M HNO3, the Sr was recovered using 2 ml of Milli-Q water.

Next, Eichrom polypropylene columns packed with 1.7 ml of homemade 2-ethylhexyl phosphonic acid mono-2-ethylhexyl ester (HEHEHP) extraction resin (similar to Eichrom LN2 resin) were used for the Sm–Nd separation. The resin columns were pre-cleaned using 4 ml of 6 M HCl twice, followed by 4 ml of Milli-Q water, and then conditioned using 4 ml of 0.1 M HCl. The REE fractions from the Sr–resin column were dried down, redissolved in 0.15 ml of 0.1 M HCl, and loaded into the HEHEHP columns. The columns were then washed using 0.25 ml of 0.1 M HCl four times. The Ce and Pr were further removed using 4.8 ml of 0.1 M HCl. Subsequently, Nd was recovered using 2 ml of 0.2 M HCl. Finally, Sm was stripped using 2.5 ml of 0.4 M HCl.

The Rb–Sr and Sm–Nd isotopic analyses were conducted using a Thermo Scientific TRITON Plus thermal ionization mass spectrometer. The Sr isotope ratios were measured using W filaments with TaF5 as the ion emitter52, and the Nd isotope ratios were measured as NdO+ also using W filaments with TaF5 as the ion emitter53. During the analytical sessions, the results were 0.710245 ± 0.000020 (2σ, n = 5) for National Bureau of Standards (NBS) 987 Sr and 0.512102 ± 0.000010 (2σ, n = 5) for JNdi-1 Nd, which are consistent with previously reported values (0.710248 ± 0.000011 (2σ) for NBS 987 Sr and 0.512115 ± 0.000007 (2σ) for JNdi-1 Nd)51,54. The procedural blanks were less than 3 pg for Rb, less than 100 pg for Sr, less than 10 pg for Sm and less than 20 pg for Nd, which were negligible compared to the amounts of Sr and Nd in the analysed samples.

The US Geological Survey BCR-2 reference material, in amounts of approximately 3 mg, was analysed alongside the CE6 samples, yielding average values (±2σ, n = 2) of 0.401 ± 0.012 for 87Rb/86Sr, 0.705017 ± 0.000025 for 87Sr/86Sr, 0.1384 ± 0.0002 for 147Sm/144Nd and 0.512625 ± 0.000020 for 143Nd/144Nd, all of which are consistent with their reference values (0.3990 ± 0.0005 for 87Rb/86Sr, 0.705013 ± 0.000010 for 87Sr/86Sr, 0.1380 ± 0.0004 for 147Sm/144Nd and 0.512637 ± 0.000012 for 143Nd/144Nd)55,56. The data are shown in Supplementary Table 5.

Petrography and mineral chemistry

The basalt fragments could be texturally subdivided into three types: porphyritic, subophitic and poikilitic (Extended Data Fig. 1). The porphyritic clasts commonly exhibit coarse-grained (50 × 300 μm) clinopyroxene phenocrysts in a fine-grained (less than 10 μm) matrix (Extended Data Fig. 1a). The matrix is composed of acicular plagioclase (An76.3–85.2), interstitial clinopyroxene and tiny (less than 5 μm) ilmenite (Extended Data Fig. 1a). Compared with the clinopyroxene phenocrysts, those in the matrix have higher FeO (32.1–38.8 wt%) but lower MgO (4.03–19.0 wt%) and Cr2O3 (0.10–1.19 wt%) contents. The ilmenite needles commonly show three directions cutting the matrix plagioclase and pyroxene, representing a late-stage crystallization phase.

The subophitic clasts show various grain sizes (20–300 μm) and consist mainly of plagioclase, clinopyroxene and ilmenite, with minor Fe–Ti-spinel (ulvöspinel), troilite, olivine and cristobalite (Extended Data Fig. 1b,c). Both the clinopyroxene and olivine have compositional zoning, with Mg-rich cores and Fe-rich rims. The plagioclase shows euhedral to subhedral shape with anorthite-rich composition (An83.6–91.9) (Supplementary Table 3). The single olivine grain with a forsterite core (Extended Data Fig. 1b) shows a large compositional range (Fo2.7–58.5) (Supplementary Table 3).

The poikilitic clasts are mainly composed of clinopyroxene, plagioclase and ilmenite, with accessory Fe–Ti-spinel (ulvöspinel) and troilite, and a mesostasis including K-feldspar, fayalite, cristobalite, baddeleyite, tranquillityite, zirconolite and phosphates (Extended Data Fig. 1d). Clinopyroxenes of various sizes are included in the coarse-grained (larger than 100 μm) plagioclases. The plagioclase is anorthite-rich (An81.9–94.3). The clinopyroxene shows a large compositional range (Wo8.5–38.9En0.2–54.9Fs20.8–89.8) and is systematically characterized by Mg-rich cores (Mg# = 27.6–66.1) and Fe-rich rims (Mg# = 0.2–39.1). The euhedral spinel has 1.9–6.5 wt% Cr2O3, 61.5–64.0 wt% FeO and 30.2–32.4 wt% TiO2. Small amounts of Fe-rich olivine (Fo1.6), associated with cristobalite, baddeleyite, tranquillityite, zirconolite and phosphates, occur as mesostasis phases representing late-stage crystallization products.

Batch melting and fractional crystallization modelling

We used trace elements to model the batch melting and fractionation crystallization processes to reproduce the REE compositions of the CE6 basalt following the same method used in refs. 23,25. The batch melting was modelled using the following equation: CL/C0 = 1/(D0 + F(1 −D0)), where CL represents the weight concentration of a trace element in the melt; C0 is the weight concentration of the trace element in the original cumulate source; F is the melt fraction; and D0 is the bulk distribution coefficient of the solid phase.

The bulk distribution coefficient is determined by multiplying each mineral partition coefficient by its modal abundance in the source. Because the CE6 basalts have a source similar to that of the Apollo 12 basalts, we adopt the modal mineralogy calculated for the Apollo 12 samples25. The REE partition coefficients for olivine57, orthopyroxene58, augite58, pigeonite59, plagioclase60 and garnet61 are listed in Supplementary Table 6.

Four mantle sources were used for the modelling: (1) 76 PCS cumulate + 0.7% TIRL of the LMO model from ref. 26; (2) 78 PCS cumulate + 1% TIRL of the LMO model from ref. 27; (3) 88 PCS cumulate + 0.3% TIRL of the LMO model from ref. 28; and (4) 78 PCS cumulate + 0.3% TIRL of the LMO model from ref. 29. The earliest LMO cumulates that underwent plagioclase separation in each model were taken as the source of the CE6 basalt. Small amounts (0.3–1.0%) of TIRL were added to reproduce the 147Sm/144Nd ratio (0.262–0.272) of the CE6 basalt source. The REE concentrations of the PCS and TIRL are listed in Supplementary Table 7. Using these bulk distribution coefficients (D0) and the solid cumulate (C0), the REE concentrations in the melt (CL) were calculated for increasing melt fractions (F). The results are shown in Extended Data Fig. 6.

The trace element concentrations in the remaining melt, following fractional crystallization, were calculated using the Rayleigh fractionation equation: CL/C0 = (1 − F)D−1, where D is the bulk distribution coefficient (the same as in the batch melting model), F is the mass fraction of crystallized solids, and C0 and CL are the element concentrations in the initial and final melt, respectively. Two scenarios are proposed to reproduce the high Sm/Yb ratio of the CE6 basalt: (1) a garnet-bearing mantle source, where the initial melts are assumed to have resulted from 1–1.5% batch melting of the 78 PCS cumulate + 0.6% TIRL of the LMO model from ref. 29, with 0.8% garnet in the residue; and (2) a high Sm/Yb ratio mantle source, where the initial melts are assumed to have resulted from a 0.7–1% batch melting of the 78 PCS cumulate of the LMO model from ref. 27, mixed with 0.8% of a high-Ti component. These results are presented in Fig. 3 and Extended Data Fig. 7.

Data availability

All data generated in this study are included in Supplementary Tables 1–7 and are available at Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15029797)62. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

No code was used in this study.

References

Neal, C. R. & Taylor, L. A. Petrogenesis of mare basalts: a record of lunar volcanism. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 56, 2177–2211 (1992).

Warren, P. H. & Taylor, G. J. in Treatise on Geochemistry (ed. Turekian, K. K.) 213–250 (Elsevier, 2014).

Wieczorek, M. A. et al. in New Views of the Moon. Reviews in Mineralogy & Geochemistry Vol. 60 (eds Jolliff, B. L. et al.) 221–364 (Mineralogical Society of America and Geochemical Society, 2006).

Yue, Z. et al. Geological context of Chang’e-6 landing area and implications for sample analysis. Innovation 5, 100663 (2024).

Qian, Y. et al. Long-lasting farside volcanism in the Apollo basin: Chang’e-6 landing site. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 637, 118737 (2024).

Guo, D. et al. Geological investigation of the lunar Apollo basin: from surface composition to interior structure. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 646, 118986 (2024).

Zeng, X. et al. Landing site of the Chang’e-6 lunar farside sample return mission from the Apollo basin. Nature Astron. 7, 1188–1197 (2023).

Zhang, Q. W. L. et al. Lunar farside volcanism 2.8 billion years ago from Chang’e-6 basalts. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08382-0 (2024).

Nelson, D. M. et al. Mapping lunar maria extents and lobate scarps using LROC image products. In 45th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, 2861 (Lunar and Planetary Institute, 2014).

Zuber, M. T., Smith, D. E., Lemoine, F. G. & Neumann, G. A. The shape and internal structure of the Moon from the Clementine mission. Science 266, 1839–1843 (1994).

Jolliff, B. L., Gillis, J. J., Haskin, L. A., Korotev, R. L. & Wieczorek, M. A. Major lunar crustal terranes: surface expressions and crust–mantle origins. J. Geophys. Res.: Planets 105, 4197–4216 (2000).

Wieczorek, M. A. et al. The crust of the Moon as seen by GRAIL. Science 339, 671–675 (2013).

Loper, D. E. & Werner, C. L. On lunar asymmetries 1. Tilted convection and crustal asymmetry. J. Geophys. Res.: Planets 107, 13-11–13-17 (2002).

Wasson, J. T. & Warren, P. H. Contribution of the mantle to the lunar asymmetry. Icarus 44, 752–771 (1980).

Zhong, S. J., Parmentier, E. M. & Zuber, M. T. A dynamic origin for the global asymmetry of lunar mare basalts. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 177, 131–140 (2000).

Parmentier, E. M., Zhong, S. & Zuber, M. T. Gravitational differentiation due to initial chemical stratification: origin of lunar asymmetry by the creep of dense KREEP? Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 201, 473–480 (2002).

Zhu, M. H., Wunnemann, K., Potter, R. W. K., Kleine, T. & Morbidelli, A. Are the Moon’s nearside–farside asymmetries the result of a giant impact? J. Geophys. Res.: Planets 124, 2117–2140 (2019).

Jones, M. J. et al. A South Pole–Aitken impact origin of the lunar compositional asymmetry. Sci. Adv. 8, eabm8475 (2022).

Zhang, N. et al. Lunar compositional asymmetry explained by mantle overturn following the South Pole–Aitken impact. Nat. Geosci. 15, 37–41 (2022).

Treiman, A. H. & Semprich, J. A dunite fragment in meteorite Northwest Africa (NWA) 11421: a piece of the Moon’s mantle. Am. Mineral. 108, 2182–2192 (2023).

Yang, W., He, Y., Qian, Y. & Yue, Z. Scientists eager for Chang’e-6 lunar farside samples to bring new discoveries. Innovation 5, 100660 (2024).

Papike, J. J., Hodges, F. N., Bence, A. E., Cameron, M. & Rhodes, J. M. Mare basalts: crystal chemistry, mineralogy, and petrology. Rev. Geophys. 14, 475–540 (1976).

Tian, H. C. et al. Non-KREEP origin for Chang’e-5 basalts in the Procellarum KREEP Terrane. Nature 600, 59–63 (2021).

Bédard, J. H. Parameterization of the Fe=Mg exchange coefficient (Kd) between clinopyroxene and silicate melts. Chem. Geol. 274, 169–176 (2010).

Hallis, L. J., Anand, M. & Strekopytov, S. Trace-element modelling of mare basalt parental melts: implications for a heterogeneous lunar mantle. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 134, 289–316 (2014).

Lin, Y., Tronche, E. J., Steenstra, E. S. & van Westrenen, W. Experimental constraints on the solidification of a nominally dry lunar magma ocean. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 471, 104–116 (2017).

Charlier, B., Grove, T. L., Namur, O. & Holtz, F. Crystallization of the lunar magma ocean and the primordial mantle–crust differentiation of the Moon. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 234, 50–69 (2018).

Rapp, J. F. & Draper, D. S. Fractional crystallization of the lunar magma ocean: updating the dominant paradigm. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 53, 1432–1455 (2018).

Jing, J.-J., Lin, Y., Knibbe, J. S. & van Westrenen, W. Garnet stability in the deep lunar mantle: constraints on the physics and chemistry of the interior of the Moon. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 584, 117491 (2022).

Neal, C. R. Interior of the Moon: the presence of garnet in the primitive deep lunar mantle. J. Geophys. Res.: Planets 106, 27865–27885 (2001).

Kesson, S. Mare basalts: melting experiments and petrogenetic interpretations. In Proc. 6th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (ed. Merriill, R. B.) 921–944 (Pergamon, 1975).

Snyder, G. A., Borg, L. E., Nyquist, L. E. & Taylor, L. A. in Origin of the Earth and Moon (eds Canup, R. M. et al.) 361–395 (Univ. Arizona Press, 2000).

Longhi, J. Experimental petrology and petrogenesis of mare volcanics. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 56, 2235–2251 (1992).

Joy, K. H. et al. Evidence of a 4.33 billion year age for the Moon’s South Pole–Aitken basin. Nat. Astron. 9, 55–65 (2024).

Frey, H. Ages of very large impact basins on Mars: implications for the late heavy bombardment in the inner Solar System. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35, L13203 (2008).

Johnson, T. E. et al. Giant impacts and the origin and evolution of continents. Nature 608, 330–335 (2022).

Li, C. L. et al. The global image of the Moon by the Chang’E-1: data processing and lunar cartography. Sci. China Earth Sci. 53, 1091–1102 (2010).

Sato, H. et al. Lunar mare TiO2 abundances estimated from UV/Vis reflectance. Icarus 296, 216–238 (2017).

Nyquist, L. Lunar Rb-Sr chronology. Phys. Chem. Earth. 10, 103–142 (1977).

Nyquist, L. et al. Rb–Sr systematics for chemically defined Apollo 15 and 16 materials. In Proc. of the 4th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (ed. Gose, W. A.) 1823–1846 (Pergamon, 1973).

Neal, C. & Taylor, L. Modeling of lunar basalt petrogenesis–Sr isotope evidence from Apollo 14 high-alumina basalts. In Proc. of the 20th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference 101–108 (1990).

Borg, L. E. et al. Mechanisms for incompatible-element enrichment on the Moon deduced from the lunar basaltic meteorite Northwest Africa 032. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 73, 3963–3980 (2009).

Elardo, S. M. et al. The origin of young mare basalts inferred from lunar meteorites Northwest Africa 4734, 032, and LaPaz Icefield 02205. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 49, 261–291 (2014).

Nyquist, L. E. et al. 146Sm–142Nd formation interval for the lunar mantle. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 59, 2817–2837 (1995).

Nyquist, L. E. & Shih, C. Y. The isotopic record of lunar volcanism. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 56, 2213–2234 (1992).

Sun, S.-s. & McDonough, W. F. Chemical and isotopic systematics of oceanic basalts: implications for mantle composition and processes. Geol. Soc. Spec. Publ. 42, 313–345 (1989).

Hurwitz, D. M. & Kring, D. A. Differentiation of the South Pole–Aitken basin impact melt sheet: implications for lunar exploration. J. Geophys. Res.: Planets 119, 1110–1133 (2014).

Potter, R. W. K., Collins, G. S., Kiefer, W. S., McGovern, P. J. & Kring, D. A. Constraining the size of the South Pole–Aitken basin impact. Icarus 220, 730–743 (2012).

Head, J. W., Wang, X., Lark, L. H., Wilson, L. & Qian, Y. Lunar nearside–farside Mare basalt asymmetry: the combined role of global crustal thickness variations and South Pole–Aitken (SPA) basin‐induced lithospheric thickening. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2024GL110510 (2024).

Xue, D.-S. et al. Quantitative verification of 1:100 diluted fused glass beads for X-ray fluorescence analysis of geological specimens. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 35, 2826–2833 (2020).

Thirlwall, M. Long-term reproducibility of multicollector Sr and Nd isotope ratio analysis. Chem. Geol.: Isot. Geosci. Sect. 94, 85–104 (1991).

Li, Q.-L., Chen, F., Yang, J.-H. & Fan, H.-R. Single grain pyrite Rb–Sr dating of the Linglong gold deposit, eastern China. Ore Geol. Rev. 34, 263–270 (2008).

Chu, Z., Chen, F., Yang, Y. & Guo, J. Precise determination of Sm, Nd concentrations and Nd isotopic compositions at the nanogram level in geological samples by thermal ionization mass spectrometry. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 24, 1534–1544 (2009).

Tanaka, T. et al. JNdi-1: a neodymium isotopic reference in consistency with LaJolla neodymium. Chem. Geol. 168, 279–281 (2000).

Weis, D. et al. High-precision isotopic characterization of USGS reference materials by TIMS and MC-ICP-MS. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 7, Q08006 (2006).

Raczek, I., Stoll, B., Hofmann, A. W. & Peter Jochum, K. High-precision trace element data for the USGS reference materials BCR-1, BCR-2, BHVO-1, BHVO-2, AGV-1, AGV-2, DTS-1, DTS-2, GSP-1 and GSP-2 by ID-TIMS and MIC-SSMS. Geostandards Newslett. 25, 77–86 (2001).

McKay, G. A. Crystal/liquid partitioning of REE in basaltic systems: extreme fractionation of REE in olivine. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 50, 69–79 (1986).

Yao, L., Sun, C. & Liang, Y. A parameterized model for REE distribution between low-Ca pyroxene and basaltic melts with applications to REE partitioning in low-Ca pyroxene along a mantle adiabat and during pyroxenite-derived melt and peridotite interaction. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 164, 261–280 (2012).

McKay, G., Le, L. & Wagstaff, J. Constraints on the origin of the mare basalt europium anomaly: REE partition coefficients for pigeonite. In Lunar Planet. Sci. Conf. 22, 883–884 (1991).

Phinney, W. C. & Morrison, D. A. Partition coefficients for calcic plagioclase: implications for Archean anorthosites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 54, 1639–1654 (1990).

Green, T. H., Blundy, J. D., Adam, J. & Yaxley, G. M. SIMS determination of trace element partition coefficients between garnet, clinopyroxene and hydrous basaltic liquids at 2–7.5 GPa and 1080–1200 °C. Lithos 53, 165–187 (2000).

Zhou, Q. et al. Repository: ultra-depleted mantle source of basalts from the South Pole–Aitken Basin. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15029797 (2025).

Lindsley, D. H. & Andersen, D. J. A two-pyroxene thermometer. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 88, A887–A906 (1983).

Grove, T. L. & Krawczynski, M. J. Lunar mare volcanism: where did the magmas come from? Elements 5, 29–34 (2009).

Arai, T., Warren, P. H. & Takeda, H. Four lunar mare meteorites: crystallization trends of pyroxenes and spinels. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 31, 877–892 (1996).

Robinson, K. L., Treiman, A. H. & Joy, K. H. Basaltic fragments in lunar feldspathic meteorites: connecting sample analyses to orbital remote sensing. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 47, 387–399 (2012).

Anand, M., Taylor, L. A., Misra, K. C., Demidova, S. I. & Nazarov, M. A. KREEPy lunar meteorite Dhofar 287 A: a new lunar mare basalt. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 38, 485–499 (2003).

Chen, Y. et al. Chang’e-5 lunar samples shed new light on the Moon. Innov. Geosci. 1, 100014 (2023).

Shearer, C., Papike, J., Galbreath, K. & Shimizu, N. Exploring the lunar mantle with secondary ion mass spectrometry: a comparison of lunar picritic glass beads from the Apollo 14 and Apollo 17 sites. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 102, 134–147 (1991).

Acknowledgements

The CE6 lunar samples were provided by the China National Space Administration. We thank R. Mitchell, Y. Chen, Q.-L. Li, J. Zhang, Y. Lin and X.-H. Li for their constructive comments, and S. Zhao for logistical support. This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42441813, 42425303, 42241103 and 62227901), the Bureau of Frontier Sciences and Basic Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences (QYJ-2025-0102 and QYJ-2025-0104) and the Key Research Program of the Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IGGCAS-202101 and IGGCAS-202401).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.-Y.W., C.L. and W.Y. designed the research. Q.Z., G.Z., Hongbo Zhang and H.-C.T. prepared the samples. Q.Z., S.Y., L.-H.J., Huijuan Zhang, H.-C.T. and L.G. performed the EMPA and SEM and energy dispersive spectrometer analyses. Q.Z., D.-S.X. and D.-P.Z. performed the major and trace element analyses. Z.C., H. Zhu, W.Y. and P.P. performed the Sr–Nd isotope analysis. H. Zhu, W.Y. and Y.L. performed the trace element modelling. Q.Z., W.Y. and X.Z. prepared the figures. Q.Z., W.Y., C.L. and F.-Y.W. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Stephen Elardo, Claire McLeod and Romain Tartese for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Backscatter electron images of typical CE6 basalt fragments with various textures.

a, Porphyritic fragment. b, c, Subophitic fragment. d, Poikilitic fragment. Detailed sample description is provided in the Methods. Cpx, clinopyroxene; Pl, plagioclase; Ol, olivine; Ilm, ilmenite.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Stereomicrographs of the four large CE6 basalt fragments selected for whole-rock analyses.

a, CE6C0000YJYX25101. b, CE6C0000YJYX48501. c, CE6C0000YJYX48901. d, CE6C0000YJYX56201.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Mineral chemistry of the CE6 basalt fragments.

a, Quadrilateral diagram of pyroxene in the CE6 basalt fragments. Temperature contours63 calculated at 0.5 GPa are shown, where 0.5 GPa was chosen according to the possible pressure range for the low-Ti basalts64. The CE5 samples are plotted (grey region) for comparison. Di, diopside; En, enstatite; Fs, ferrosilite; Hd, hedenbergite. b, Ti# versus Mg# diagram of the pyroxene from CE6 basalt fragments. Fields represent variation in Mg# and Ti# in Apollo very low-Ti, low-Ti, and high-Ti mare basalts65,66. c, Ternary diagram of plagioclase in the CE6 basalt. An, anorthite; Ab, albite; Or, orthoclase. d, Comparison of olivine compositions in CE6 basalts with those within the CE5, Apollo 12 and Apollo 15 basalts23,67. Data are provided in Supplementary Table 3.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Whole-rock major element compositions for the CE6 basalt fragments compared to various types of lunar mare basalts.

a, SiO2 versus Mg#. b, TiO2 versus Mg#. c, Al2O3 versus Mg#. d, Cr2O3 versus Mg#. e, FeO versus Mg#. f, CaO versus Mg#. g, Na2O versus Mg#. h, K2O versus Mg#. i, P2O5 versus Mg#. The Apollo and Luna data are from the mare basalt database of Clive Neal (https://www3.nd.edu/~cneal/Lunar-L/). The CE5 data are from ref. 68. Abbreviation: 251, CE6C0000YJYX25101.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Trace element spider diagram and REE patterns for the CE6 basalts compared to low-Ti lunar mare basalts.

a, Chondrite-normalized trace element spider diagram. b, Chondrite-normalized REE patterns. The Apollo and Luna data are from the mare basalt database of Clive Neal (https://www3.nd.edu/~cneal/Lunar-L/). The CE5 data are from ref. 68. Normalization values are from ref. 46.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Chondrite-normalized REE patterns and REE modelling for various degrees of partial melting of the mantle sources.

a, REE modelling using the LMO model from ref. 26. b, REE modelling using the LMO model from ref. 27. c, REE modelling using the LMO model from ref. 28. d, REE modelling using the LMO model from ref. 29. The earliest LMO cumulates that underwent plagioclase separation in each model are taken as the source of the CE6 basalt. Small amounts (0.3–1.0%) of trapped instantaneous residual liquid (TIRL) were added to reproduce the measured source 147Sm/144Nd ratio of 0.262–0.272. As the CE6 basalts have a similar source as Apollo 12 basalts, we adopt the modal mineralogy calculated for Apollo 12 (52% olivine, 23% orthopyroxene, 23% pigeonite, 2% augite; ref. 25). The melts are produced after 0.1–5% partial melting of the mantle sources. Model parameters are listed in Supplementary Tables 6, 7. Detailed description of batch melting and fractional crystallization modeling is provided in the Methods. Normalization values are from ref. 46. Data of the Apollo basalts (A12051 and A15545) are from the mare basalt database of Clive Neal (https://www3.nd.edu/~cneal/Lunar-L/). The modelling results indicate that partial melting of these mantle sources is unable to reproduce the REE composition of the CE6 basalt, particularly the steep heavy-REE pattern. The REE abundances of the CE6 basalt are the average composition of the three fragments (CE6C0000YJYX48501, CE6C0000YJYX48901, and CE6C0000YJYX56201). The error bars are one standard deviation.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Sm/Yb versus La plot for mare basalts and Apollo 17 volcanic glass.

a, Modelling of the deviation from a garnet-bearing mantle source. The dashed lines denote the melts produced by partial melting of the mantle source (78 PCS + 0.6% TIRL; PCS, percent crystallized solid; TIRL, trapped instantaneous residual liquid) with various proportions of garnet retained in the residue. The CE6 basalt exhibits high Sm/Yb ratios, which require 0.8% garnet retained in the mantle residue. b, Modelling of the deviation from a high Sm/Yb ratio mantle source. The purple lines denote the melts produced by partial melting of the high Sm/Yb ratio mantle source (78 PCS + 0.8% high-Ti component). The high Sm/Yb ratio of the CE6 basalt can also be reproduced by partial melting of a high Sm/Yb ratio mantle source. The Apollo mare basalt data are from the mare basalt database of Clive Neal (https://www3.nd.edu/~cneal/Lunar-L/). The Apollo 17 volcanic glass data are from ref. 69.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Tables

Supplementary Tables 1–7.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, Q., Yang, W., Chu, Z. et al. Ultra-depleted mantle source of basalts from the South Pole–Aitken basin. Nature 643, 371–375 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09131-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09131-7

This article is cited by

-

An impact-related origin for lunar magmatic rocks?

Nature Astronomy (2025)

-

A more reduced mantle beneath the lunar South Pole–Aitken basin

Nature Communications (2025)

-

First returned rock samples shine a light on the Moon’s ‘dark side’

Nature (2025)