Abstract

Ultimate limits for the sensing of fields and forces are set by the quantum noise of a sensor1,2,3. Entanglement allows for suppression of such noise and for achieving sensitivity beyond standard quantum limits4,5,6,7. Applicability of quantum optical sensing is often restricted by fixed wavelengths of available photonic quantum sources. Another ubiquitous limitation is associated with challenges of achieving quantum-noise-limited sensitivity in the acoustic noise frequency range relevant for several applications. Here we demonstrate a tool for broadband quantum sensing by performing quantum state processing that can be applied to a wide range of the optical spectrum and by suppressing quantum noise over an octave in the acoustic frequency range. An atomic spin ensemble is strongly coupled to one of the frequency-tunable beams of an Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen (EPR) source of light. The other EPR beam of light, entangled with the first one, is tuned to a disparate wavelength. Engineering the spin ensemble to act as a negative-mass or positive-mass oscillator, we demonstrate frequency-dependent quantum noise reduction for measurements at the disparate wavelength. The tunability of the spin ensemble enables targeting quantum noise in a variety of systems with dynamics ranging from kHz to MHz. As an example of broadband quantum noise reduction in the acoustic frequency range, we analyse the applicability of our approach to gravitational-wave detectors (GWDs). Other possible applications include continuous-variable quantum repeaters and distributed quantum sensing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Measurements on mechanical objects, spanning masses from pg to kg, and collective atomic systems, from ultracold atoms to room-temperature ensembles, have reached regimes dominated by quantum dynamics1,2,3,4,5,6,7. These systems are probed by light at optical or microwave wavelengths, in the regime where the quantum coherent interaction surpasses the thermal decoherence. The measurement imprecision owing to the quantum fluctuations of light and the measurement-driven disturbances known as the quantum backaction (QBA) collectively define the minimum total measurement noise called the standard quantum limit (SQL). This constraint sets the limit on sensitivity of quantum sensors of motion8,9,10,11 and restricts applications ranging from biomedical sciences12 to the exploration of physics beyond the standard model13.

Unlike a standard optomechanical oscillator14, an atomic spin oscillator can straightforwardly be engineered to exhibit an effective negative mass or, equivalently, frequency15. Theoretical proposals for measurements surpassing the SQL using an effective negative mass to counterbalance the QBA of a standard oscillator have been put forward16,17,18. QBA evasion by coupling a spin oscillator to a macroscopic mechanical oscillator19,20 and multitone readout of two micromechanical oscillators21, enabling entanglement of the two systems, have been experimentally demonstrated. However, in those experiments, both systems had to interact with light at a specific wavelength. If a spin oscillator is used for QBA evasion, this wavelength is defined by the atomic transition used to couple the spin to light. Another limitation of those initial demonstrations was the requirement for the frequencies of the oscillators to be in the MHz range, whereas the quantum noise reduction was achieved within a bandwidth much smaller than that frequency. Other methods of narrowband sub-SQL measurements include variational readout4,11,22,23.

Here we report a hybrid quantum network for the broadband suppression of quantum noise beyond the SQL in the acoustic frequency range with a bandwidth of noise reduction that is comparable with the oscillation frequency. Our protocol relies on two key elements: a two-colour EPR light source and a negative-mass spin ensemble. The EPR source establishes a quantum-entanglement link between the sensor and the negative-mass spin oscillator. The broad tunability of the spin allows us to tailor the frequency dependence of the entanglement correlations and to obtain the desired broadband quantum noise reduction. The system can, in principle, achieve complete quantum noise cancellation24,25, whereas the sensing wavelength can be chosen across a broad range of the optical spectrum. These features make the present approach useful in several applications in which flexibility of the probe light wavelength and the eigenfrequency of the sensor is required.

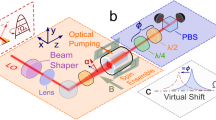

The main elements of the proposed quantum network are presented in Fig. 1a. We consider a sensor measuring a force f and probed by light at a wavelength λs, whereas an atomic oscillator with tunable dynamics interacts with light at a wavelength λi. The light phase quadrature after passing through the sensor is \({P}_{{\rm{s}}}={p}_{{\rm{s}}}+{{\mathcal{K}}}_{{\rm{s}}}{x}_{{\rm{s}}}+f\), in which (ps, xs) and (Ps, Xs) are input/output light canonical variables obeying the commutation relations [xs(Ω), ps(Ω′)] = [Xs(Ω), Ps(Ω′)] = iδ(Ω + Ω′). As well as the imprecision noise ∝ ps, the interaction induces the QBA ∝ xs, which scales with the frequency-dependent coupling strength \({{\mathcal{K}}}_{{\rm{s}}}(\varOmega )\). Similarly, after interaction with the atomic spin ensemble, the light phase quadrature reads \({P}_{{\rm{i}}}={p}_{{\rm{i}}}+{{\mathcal{K}}}_{{\rm{a}}}(\varOmega ){x}_{{\rm{i}}}\). We demonstrate that we can engineer the spin oscillator to provide a counter-response of the sensor \({{\mathcal{K}}}_{{\rm{a}}}(\varOmega )=-\,{{\mathcal{K}}}_{{\rm{s}}}(\varOmega )\) corresponding to a negative-mass oscillator. The ideal EPR state of light between signal and idler wavelengths λs and λi introduces correlations with the uncertainties Δ(pi + ps) → 0 and Δ(xi − xs) → 0. Thus, combining the negative-mass response with EPR light, it is possible to suppress both the quantum imprecision and the backaction noise, \(\Delta ({P}_{{\rm{s}}}+{P}_{{\rm{i}}})=\Delta ({p}_{{\rm{s}}}+{p}_{{\rm{i}}})+{{\mathcal{K}}}_{{\rm{s}}}\Delta ({x}_{{\rm{s}}}-{x}_{{\rm{i}}})+f\to f\), leading to a broadband sensitivity gain.

a, General parallel scheme for the sensitivity enhancement of a quantum-noise-limited sensor. b, Layout of the experimental set-up. The spin ensemble is probed by light at 852 nm (idler), which is entangled with a 1,064 nm (signal) optical field. A suitably engineered atomic spin ensemble provides the required quadrature-rotation dynamics, described by Φ(Ω). The two fields are analysed by the corresponding homodyne detectors, with θs defining the quadrature phase of the signal field and the phases ϕi and δθi defining the detection phase θi for the idler field. Conditioning the signal photocurrent on the idler that has interacted with the spin ensemble results in the noise-reduction spectrum required for a particular application. c, The noise in the phase space for the idler field as a function of the frequency Ω. Far away from Ωa, the idler noise (blue-shaded area) corresponds to the EPR state. Closer to Ωa, the idler experiences a single-axis-twisting transformation as a result of interaction with the atomic spin ensemble. d, Conditioning the signal on the idler by the post-processing of the photocurrents, as shown in panel b, results in conditional squeezing in the signal observable Qs|i(θs), for which the squeezing phase θs = Φ(Ω) changes with Ω, as illustrated by the rotated red-shaded ellipses. This process counteracts the quantum noise induced by optical probing of the force sensor by reducing the amplitude noise at Ωa and reducing the phase noise far away from Ωa, thus enabling broadband quantum-enhanced sensing. Dashed circles indicate vacuum noise.

Hybrid quantum network

The experimental implementation, depicted in Fig. 1b, involves generating an EPR state of two optical fields: an idler at 852 nm and a signal at 1,064 nm. The idler passes through the spin oscillator prepared in an effective-negative-mass configuration. After the spin–idler interaction, we measure the quantum states of light in both the idler and the signal arms. We demonstrate that, applying the results of the homodyne measurement in the idler arm to the photocurrent in the signal arm, we obtain frequency-dependent conditional squeezing in the latter. The optimal conditional squeezing is obtained at the readout phase angle Φ(Ω) determined by the quantum dynamics of the spin oscillator, characterized by \({{\mathcal{K}}}_{{\rm{a}}}(\varOmega )\). This conditioning is equivalent to the preparation of the squeezed state that compensates for the rotation of the signal output state induced by the target sensor’s QBA \({{\mathcal{K}}}_{{\rm{s}}}(\varOmega )\), thus maintaining noise reduction across all frequencies.

Although the approach we present is broadly applicable, we highlight its potential by examining quantum enhancement in GWDs24. Present GWDs are now operating near the SQL3,4 and rely on frequency-dependent squeezing to broaden their observational range26,27 and to demonstrate squeezing of the quantum noise in the interferometer28. This technique29, which uses a 300-m filter cavity to rotate the squeezed vacuum state, with up to 10-km-long cavities planned in the future, is effective but challenging to scale, particularly for the anticipated detuned dual-recycling Fabry–Pérot Michelson interferometer design of the next GWD generation30. In this configuration, the detector susceptibility will require an additional filter cavity11. Different approaches are at present under investigation31,32,33, but they are strongly limited by interdependencies on the interferometer design34. The new method for generating frequency-dependent squeezing proposed here achieves a performance comparable with that of the filter-cavity approach using a more compact and flexible set-up.

Atom–light two-colour quantum channel

Our EPR source design, based on a nondegenerate optical parametric oscillator (NOPO) below threshold, enables the frequency-tunable entangled modes to couple to a specific target system (see Methods). Here we choose the signal at λs = 1,064 nm compatible with contemporary GWDs and the idler at λi = 852 nm tuned to the 133Cs D2 line. Owing to the parametric amplification, the signal and idler individually show a noise level higher than that of vacuum fluctuations (shot noise). EPR correlations allow measurement on one mode to be used to infer the measurement outcome of another mode with precision below the vacuum fluctuations, resulting in conditional squeezing35. For a given optical field k, the quadratures xk (amplitude) and pk (phase) define a general detection quadrature qk(θk) = xksinθk + pkcosθk, selected by the homodyne angle θk. We consider the case of measurements on the idler field used to estimate the outcome of measurements on the signal field. In this case, the signal field is conditionally squeezed if the inferred variance obeys Var(qs(θs) + gqi(θi)) < 1/2, where 1/2 is the vacuum noise variance. The gain factor g is selected to minimize the variance. In the output of the NOPO, the correlations are maximized by choosing quadratures that satisfy the condition for the detection angles θi = −θs (ref. 35), in which the phases are referenced to the pump beam phase (see Methods). For the signal and idler on resonance and the noise sideband frequency well within the NOPO cavity bandwidth, the conditional squeezing is frequency-independent. The bottom blue trace in Fig. 2a shows 3 dB of signal squeezing conditioned on the idler. For comparison with other experiments, we point out that we also measured 6 dB of two-mode entanglement according to the Duan–Simon criterion as shown in Extended Data Fig. 2a.

The spin ensemble is set to the positive-mass configuration with Ωa/2π = 54 kHz (marked by the thick dashed vertical lines) and the idler field is detected at phase quadrature θi = 0°. a, Conditional noise relative to the signal shot noise for different readout angles θs. The blue and grey traces represent frequency-independent conditional squeezing and signal-field shot noise, respectively, measured by setting the Larmor frequency to 1 MHz. For each measurement phase, the dark dashed curves represent the expected theoretical noise spectra. The red data points with error bars are extracted from 60 samples around the minimal noise for each phase. The red solid curve is the conditional squeezing predicted by the model. b, Contour spectrogram of the recorded conditional squeezing, illustrating its dependence on frequency Φ(Ω), indicated by the white dashed-dotted curve. The bandwidth δΩSQL/2π ≈ 4.1 kHz over which the squeezing phase rotates from 90° to 45° is indicated in both panels by the dashed vertical lines (see comments in the text).

Using optical pumping collinear with the magnetic field, we prepare the atomic ensemble in a highly polarized state, with the orientation of the collective atomic spin aligned along the bias field. The entangled idler beam is overlapped with an orthogonally polarized strong probe laser beam, whose polarization is adjusted to minimize the effect of higher-order light–atoms interactions36. The strong beam also serves as the local oscillator (LOi); see Fig. 1b and details in Extended Data Fig. 1. Both beams are detuned by 1.6 GHz from the transition 62S1/2, F = 4 ↔ 62P3/2, F′ = 5. The detuning provides sufficient quantum dispersive coupling to the atomic ensemble while substantially reducing the deleterious absorption.

After interacting with the atomic ensemble, the quantum state of the idler field is measured with a polarimetric homodyne detector. The detection set-up comprises a quarter-wave plate that introduces a phase offset δθi in the idler field (Fig. 1b). This phase shift contributes to the detection phase θi and enables the observation of the ponderomotive squeezing induced by the atomic spin ensemble36. The signal beam propagates to the second homodyne detector, with the detected quadrature controlled by the LOs phase θs. The photocurrent corresponding to each homodyne detector is recorded for post-processing. A detailed description of the experimental set-up is given in Methods.

Tunable frequency-dependent conditional squeezing

The atomic spin ensemble affects the phase quadrature of the idler beam in a frequency-dependent way

while leaving the amplitude quadrature unchanged Xi(Ω) = xi(Ω) (ref. 19). Pi(Ω) contains contributions from both the input phase quadrature pi and the QBA, which is proportional to xi. In the context of spin, this transformation is called one-axis twisting37,38, whereas in the context of light variables, it is known as ponderomotive squeezing11, which can be seen as an effective Kerr nonlinearity39. To achieve a broadband quantum noise reduction, the one-axis twisting should be made frequency-dependent. Such frequency dependence is delivered by the atoms as shown in Fig. 1c. Its frequency dependence is expressed by

in which the readout rate Γa quantifies the interaction strength between the spin oscillator and light36, γa is the spin decay rate and Ωa is the Larmor frequency; Na(Ω) represents the atomic noise associated with the finite decay γa > 0, contaminating the output state of light (equation (1)). The sign of Ωa is determined by that of the effective oscillator mass and can be switched from positive to negative by adjusting the bias-field direction relative to the collective spin orientation, whereas varying the bias-field strength tunes |Ωa| (refs. 15,19).

Efficient broadband quantum noise reduction in our scheme requires strong light–spin coupling, which is characterized by high quantum cooperativity Cq = Γa/(γa(1 + 2nth)) (ref. 20), in which nth is the thermal occupation. We characterize the cooperativity by observing ponderomotive squeezing generated by the spin oscillator ranging from 1 MHz down to 3 kHz (ref. 36) (see Methods and Extended Data Fig. 2b).

The effect of the spin oscillator on the quantum state of the idler light (equation (1)) is, in our experiments, effectively a frequency-dependent rotation of the input quadratures determined only by \({{\mathcal{K}}}_{{\rm{a}}}(\varOmega )\) (equation (2)).

We illustrate this for our experimental regime of slow spin decay \({\gamma }_{{\rm{a}}}^{2}\ll {\varOmega }_{{\rm{a}}}^{2},{\varGamma }_{{\rm{a}}}^{2}\), in which it is permissible to let γa → 0 in equation (2); this yields a real \({{\mathcal{K}}}_{{\rm{a}}}\) factor, equivalent to a purely in-phase atomic response (see Methods for details). Focusing on the quantum noise contribution of light in equation (1), we rewrite it as Pi(Ω) = z(Ω)(pi(Ω)cosΦ(Ω) − xi(Ω)sinΦ(Ω)), thereby separating the atomic processing of light into a quadrature rotation

and an overall amplification factor \(z(\varOmega )=\sqrt{1+{{\mathcal{K}}}_{{\rm{a}}}^{2}(\varOmega )}\). We obtain the signal-arm measurement photocurrent conditioned on the measurements of the idler quadrature Pi as

Using a suitably optimized gain g(Ω), we achieve conditional squeezing of the idler beam with frequency-dependent squeezing angle Φ(Ω) as shown in Fig. 2b, corresponding to the rotation induced on the idler by the spin ensemble (Fig. 1c). That is, for each frequency component Ω there exists an optimal signal detection phase θs = Φ(Ω) required to witness the optimal noise reduction.

Φ(Ω) ranges from 0° to 180° as the Fourier frequency is scanned from Ω ≫ |Ωa| + Γa to Ω ≪ |Ωa| − Γa, crossing θs = 90° at the Larmor frequency Ω = |Ωa|. Thus, the squeezing ellipse undergoes complete rotation over the frequency range with the bandwidth 2Γa. Hence, the dependence of the rotation on the frequency can be changed by adjusting the Larmor frequency Ωa and the spin readout rate Γa. The atomic noise Na(Ω) in equation (1) does not influence the squeezing angle Φ(Ω) but degrades the degree of conditional squeezing (see Methods).

In Fig. 2, we show the noise reduction obtained with the spin oscillator in the effective positive-mass configuration; the observed behaviour is consistent with the squeezing-angle dependence Φ(Ω) required for quantum noise reduction in a negative-mass sensor.

Reversing the sign of the effective mass changes the sign of Ωa in \({{\mathcal{K}}}_{{\rm{a}}}\) (equation (2)) and, consequently, the direction of the frequency-dependent rotation Φ(Ω) of the squeezing (equation (3)). Specifically, the effective negative mass of the spin oscillator provides the opportunity to counterbalance the QBA from radiation pressure in quantum optomechanics. In the limit |Ωa|, γa ≪ Ω, the phase Φ(Ω) = −arctan(ΓaΩa/Ω2) mimics the optomechanical interaction with a free-mass object11. The conditional squeezed state thus becomes compatible with GWDs in a simple Michelson configuration and potentially allows for broadband quantum noise reduction in such an interferometer.

Quantum noise suppression in the acoustic band

The optimal gain g(Ω) is applied for each θs to maximize the noise suppression based on the entire idler measurement record (see Methods). The noise reduction below the shot noise of the signal beam in a broad frequency range confirms that the atomic ensemble imposes the phase shift on the conditional squeezing angle ranging from θs = 0° to θs ≈ 180°. As shown in Fig. 2, the theoretical noise spectra calculated on the basis of independent calibrations as described in Methods coincide well with the experimental data. The quantum noise suppression does not reach the level set by the initial entangled state of light owing to the broadband spin noise (see Methods) at higher Fourier frequencies and because of the atomic thermal noise near Ωa.

Following the approach used in Fig. 2a, 18 conditional squeezing measurements are combined to construct a contour spectrogram, in which the conditional noise is presented as a function of both signal homodyne phase θs and Fourier frequency Ω. The result in Fig. 2b shows the map of the frequency-dependent rotation Φ(Ω). The observed trajectory matches well with the theoretical model (white dashed-dotted curve) based on the calibrated experimental values of Γa, γa and Ωa (see Methods). The model predicts that, in the limit of |Ωa| ≫ Γa, γa, the bandwidth δΩSQL > 0 over which the squeezing phase rotates from the amplitude quadrature (Φ(Ωa) = 90°) to halfway between amplitude and phase quadratures (Φ(Ωa + δΩSQL) = 90° ∓ sign(Ωa)45°) is δΩSQL/2π ≈ Γa/4π = 4.1 kHz. As shown in Fig. 2a, this value aligns well with the experimentally observed frequency difference between the Larmor frequency and the Fourier frequency, at which the squeezing ellipse is rotated by 45°.

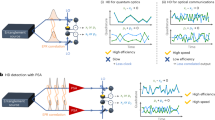

After validating the model, we test the system tunability by lowering the oscillator frequency into the audio band, |Ωa|/2π ≈ 10 kHz. We optimized the system, increasing the stability of the EPR source and its coupling to the atomic spin oscillator. The results are shown in Fig. 3. For the positive-mass spin configuration (Fig. 3a,b), we confirm the broadband conditional squeezing capabilities of our system by measuring the bandwidth of the phase shift δΩSQL/2π ≈ 4.1 kHz comparable with the central frequency |Ωa| and in agreement with the theoretical model (see Methods). We then optically pump the spin oscillator into the negative-mass configuration (Fig. 3c,d). Here we demonstrate the ability to invert the direction of the phase shift of conditional squeezing while keeping all of the other reference parameters unchanged. The results shown in Fig. 3d correspond to the desirable configuration for quantum noise reduction in optomechanical sensors including GWDs, as the produced rotation of the squeezing phase Φ−(Ω) counteracts the QBA effect for a positive-mass quantum system, such as the mirrors of an interferometer.

The inferred quantum noise for the signal field in three spin-ensemble configurations in units of the signal-field shot noise. a,c,e, Inferred noise as a function of Fourier frequency, recorded at different readout angles θs for specific ensemble configurations. In each plot, the data points represent the measured minimal conditional noise for each readout angle and the associated thick solid curve shows the prediction from our model. The blue traces at −3 dB in a,c,e show frequency-independent conditional squeezing, measured by detuning the Larmor frequency |Ωa|/2π up to 1 MHz. By combining the data from the joint measurements over the continuous phase range (0° to 180°), we construct the bottom contour spectrograms. a,b, Positive mass: the frequency dependence of squeezing angle Φ+(Ω) with Ωa/2π = 10.7 kHz and the phase offset δθi = 0° adjusted by quarter-wave plate in the idler optical mode. c,d, Negative mass: with Ωa/2π = −10.5 kHz and δθi = 0°, the frequency dependence Φ−(Ω) is opposite to the case of the positive mass. e,f, Negative mass with virtual frequency shift: for the same ensemble parameters as in c,d, the phase offset is set to δθi ≈ 45°. The dark grey dashed vertical line, representing the frequency corresponding to the minimum quantum noise for the signal phase of θs = 90° in e, indicates an effective frequency downshift of about 2.7 kHz (as shown by the red arrow) relative to the Larmor frequency, marked by the light grey dashed line. In f, this frequency downshift also sharpens the frequency-dependent phase rotation (as indicated by the dashed-dotted curve ΦVR(Ω) relative to the dashed curve Φ−(Ω)). Meanwhile, we observe enhanced squeezing levels above the Larmor frequency |Ωa| compared with c,d. The total detection phase θi = 0° was chosen for all three configurations. (The common legend for a,c,e indicates coarse values for the detection phase θs, relative to which the actual values used in the theoretical curves are offset by −2.1°, −1.5° and +5°, respectively, for the three datasets). See Extended Data Figs. 4 and 5 for the analysis of the error bars.

The phase offset δθi in the entangled idler field owing to the quarter-wave plate, shown in the upper panel of Fig. 3e, affects the functional dependence of Φ(Ω). The implications of rotating the quadrature basis after probing the spin ensemble are shown in the right column of Fig. 3. We highlight the decrease of the effective spin oscillator frequency by about 2.7 kHz and the change of the bandwidth δΩSQL of the squeezing rotation down to about 2.5 kHz, comparing the spectrogram in Fig. 3f for δθi ≈ 45° to Fig. 3d, in which δθi = 0° was set. The observed phenomenon is attributed to the virtual rigidity effect40, which effectively modifies the oscillator response to the quantum noise of the probe light as if its resonance frequency and the readout rate were changed36, leading to Φ(Ω) → ΦVR(Ω). This effect, rooted in the atomic ponderomotive squeezing and variational measurement, also alters the degree of conditional quantum noise reduction (blue data points) for different parts of the spectrum, as shown in Fig. 3e (for details, see Supplementary Information Section I). Overall, the control of the phase shift δθi in the entangled idler field provides extra flexibility for tuning the features of frequency-dependent squeezing and for the corresponding optimization of the quantum noise reduction25.

The approximation \({{\mathcal{K}}}_{{\rm{a}}}\approx {\varGamma }_{{\rm{a}}}/{\varOmega }_{{\rm{a}}}\) for the atomic coupling factor applies at Ω ≪ |Ωa|. Hence, as the Larmor frequency approaches the readout rate, the full phase rotation range for the conditional squeezing cannot be achieved for the upper (lower) range with the positive-mass (negative-mass) spin oscillator. This limitation on the phase rotation [0°, 140°] ([40°, 180°]) is seen in Fig. 3b,d, despite the increased technical noise near DC frequencies. The readout rate and the decay can be adjusted by carefully engineering the light–spin interaction36.

Outlook

We have demonstrated that a tunable entangled light source coupled to a spin oscillator with an adjustable oscillation frequency allows, in principle, for the reduction of both the shot noise and the QBA noise of a measurement. This reduction can be achieved at widely tunable optical wavelengths and within a broad noise frequency range. These features make our hybrid quantum system a promising candidate for sensitivity improvement in the next generation of GWDs.

Although our results exhibit less conditional squeezing compared with the original frequency-independent squeezing level, our model suggests that reducing the broadband spin noise by a factor of six and the spin thermal occupation by a factor of three would be sufficient to achieve the frequency-dependent squeezing level across the full bandwidth limited only by the degree of EPR correlations of light as illustrated by Extended Data Fig. 3. The reduction in thermal occupation is a combination of optical pumping improvement and mitigation of the classical noise of the laser36 (see details in Supplementary Information Section IIB). The degree of observed EPR correlations can be further increased by reducing the overall optical losses and by mitigation of the optical phase fluctuations, allowing higher parametric gain in the NOPO41.

With the atomic spin oscillator maintaining quantum-noise-limited performance down to the gravitational-wave backaction-dominant regime, our system is analogous to the filter cavity implementations26. We infer that the squeezing phase rotation provided by the 8-cm-long cell in the present work is equivalent to the rotation imposed by a 5-m-long Fabry–Pérot filter cavity with finesse approximately 6,000 (ref. 42), as follows from the results shown in Fig. 3d (see Supplementary Information Section III). The length of the equivalent optical cavity is effectively extended to 10 m when the virtual rigidity downshift in Fig. 3f is applied.

The steps required for application of our method in the bandwidth of the existing GWDs mainly involve reduction of the acoustic noise. It can be achieved, for example, by placing the experimental set-up in vacuum, similar to the filter cavities of LIGO and Virgo. Under such conditions, the lower spectral bound of the QBA-dominated performance of our system can be extended to 1–2 kHz. Using the 1–2-kHz shift of the response function to lower frequencies by virtual rigidity demonstrated in the present paper, the effective quantum noise reduction down to the low-frequency end of LIGO and Virgo can be achieved25. Another condition for improved low-frequency performance of our system—the long coherence time of the spin oscillator—has already been achieved at our lab using an atomic cell with a cross-section of 5 × 5 mm2 for which 6 Hz intrinsic decoherence rate has been observed36.

The spin system is flexible in both its resonance frequency and bandwidth and is scalable owing to its relative compactness and simplicity. The protocol can be extended using several ensembles and, in this way, more intricate spectral profiles Φ(Ω) for quantum noise reduction within a required spectral range can be engineered. In the context of the quantum noise reduction in GWDs, a cascade of spin ensembles resembles the implementation of a cascade of filter cavities11,43.

The EPR source design can be adapted to link our spin oscillator with systems ranging from optomechanics to atomic physics. The required signal wavelength ranging from 700 to 2,000 nm can be achieved by using a suitable signal laser and a corresponding nonlinear medium for parametric downconversion. By making use of this opportunity, we foresee potential for other applications in the field of quantum-enhanced metrology, such as detection of quantum motion of nanoparticles and cantilevers44,45, in which broadband, frequency-dependent engineering of the quantum noise of light is required.

To the best of our knowledge, the demonstrated system is the first combination of multicolour continuous-variable entangled light modes with a quantum memory46,47, which is the backbone of proposals for a continuous-variable quantum repeater48. The versatility of our hybrid network enables quantum protocols coupling efficient atom–light interfaces49 to systems ranging from the nanoscale to the macroscale50,51.

Methods

A detailed layout of the experimental set-up is shown in Extended Data Fig. 1. Below, we discuss the main components of the system and their characterization.

EPR source

As shown in Extended Data Fig. 1, two lasers at 852 nm (SolsTiS, M Squared) and 1,064 nm (Mephisto, Innolight) drive the sum frequency generation producing the pump beam at 473 nm for a NOPO, which generates the EPR state of light. The NOPO cavity design and the operation principle are reported in ref. 41. The cavity has a bow-tie configuration with a periodically poled potassium titanyl phosphate nonlinear crystal. The resonance of the NOPO for the 852-nm and 1,064-nm downconverted modes is maintained by locking the cavity to the 1,064-nm laser and locking the 852-nm laser to the cavity, using beams counterpropagating to the EPR modes. To achieve quantum-noise-limited performance in the audio frequency band, we suppress the classical noise of the probe laser using an active noise eater and implement the robust control of the EPR state phases, as described in depth in V. Novikov et al., manuscript in preparation.

The EPR output modes of the NOPO cavity are separated by a dichroic mirror. The signal beam at 1,064 nm is mixed with the corresponding LOs on a 50:50 beam splitter and the canonical operators (xs, ps) are measured using a balanced homodyne detector (Extended Data Fig. 1). The 852-nm idler beam is combined with an orthogonally polarized probe beam LOi on a polarizing beam splitter and polarization homodyning is performed.

We observe 9 dB of two-mode squeezing, corresponding to 6 dB of conditional squeezing of the signal field when the two EPR beams are analysed directly (the idler bypasses the atoms) (A. Grimaldi et al., manuscript in preparation). The electronic noise floor is more than 17 dB below the shot noise level.

Before entering the atomic ensemble, the combined idler beam and LOi are shaped into a square top-hat profile, enabling the optimal readout of atomic spins (see the ‘Atomic spin oscillator’ section below). To characterize the overall propagation losses, including those from the cell windows, beam shaper and other optical elements, a measurement with the Larmor frequency tuned to 1 MHz, beyond the detection frequency band, has been performed.

We observe roughly 3.3 dB conditional squeezing from 3 to 60 kHz relative to the signal vacuum noise, as shown in Extended Data Fig. 2a. Noise peaks at 26 and 36 kHz are experimental artefacts caused by the intensity noise eater. The theory of the conditional squeezing, detailed in Supplementary Information Section I, allows us to extract a squeezing factor r = 1.42 and an unbalanced detection efficiency of ηs ≈ 0.92 for the signal arm and ηi = ηi,outηi,in ≈ 0.8 for the idler arm by fitting the measured power spectrum densities. See Extended Data Table 1 for parameter values.

Atomic spin oscillator

The atomic spin oscillator is implemented in a 133Cs gas of NCs ≈ 1010 atoms in a 2 × 2 × 80-mm3 glass channel inside a vacuum-tight glass cell. The cell windows are anti-reflection coated and the inner walls are coated with an anti-relaxation paraffin material to minimize the decoherence from spin–wall collisions. The atomic vapour density in the cell is defined by the temperature of the caesium droplet in the stem of the cell, which was set to about 40 °C in the experiment. A multilayer magnetic shield around the cell provides isolation from the Earth’s magnetic field and other high-frequency magnetic noise, whereas a set of coils running low-noise DC currents generates a highly homogeneous bias magnetic field within the cell. By adjusting the DC current, we can control the Larmor frequency |Ωa| from 1 MHz down to 3 kHz, maintaining quantum-dominated performance throughout this frequency spectrum36.

As depicted in Extended Data Fig. 1, the vapour cell is illuminated by two optical fields. A circularly polarized optical repumping field, propagating transversely, prepares the spin ensemble in the hyperfine |F = 4, mF = 4⟩ or |F = 4, mF = −4⟩ ground state manifold with 82% efficiency, enabling it to function as a macroscopic spin oscillator with an adjustable sign of the effective mass.

The probe beam is blue-detuned by 1.6 GHz from the D2 line F = 4 → F′ = 5 transition to eliminate the absorption. The polarization of the probe entering the atomic ensemble is chosen to optimize the light–spin interaction, as discussed in the main text20,36. The light–atoms interaction strength is characterized by the readout rate \({\varGamma }_{{\rm{a}}}\propto {g}_{{\rm{cs}}}^{2}{{\mathcal{S}}}_{1}\,{J}_{x}\,\propto d\), in which gcs is the single photon–atom coupling rate that depends on the probe detuning and \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{1}\) is a Stokes parameter proportional to the power of the probe light. The optical depth of the spin ensemble d ∝ Jx ∝ NCs, in which Jx is the macroscopic component of the collective spin and NCs is the number of atoms36.

The spin oscillator experiences depolarization, primarily because of the spontaneous emission that occurs in the presence of the probe field. This leads to the spin thermal noise imprinted onto the output probe beam. In the regime of strong light–atom coupling Γa ≫ γa, the QBA induced by the probe dominates over the atomic thermal noise. Atoms that maintain interaction with the probe by several passages across the probe beam during the coherent evolution time contribute to the narrow-band atomic response limited by the spin decoherence rate γa. The remaining atoms contribute to faster-decaying atomic modes, leading to further, broadband atomic noise with the bandwidth of γbb ≫ γa (refs. 20,52,53). To minimize the broadband noise, the input field, comprising two orthogonally polarized fields (idler and LOi), is shaped into a collimated square top-hat beam with a seventh-order super-Gaussian waist of 1.7 mm by the top-hat shaper, as shown in Extended Data Fig. 1. It propagates through the cell with the filling factor of approximately 80% without introducing extra losses. The effect of the remaining broadband noise is illustrated in Extended Data Fig. 2.

To characterize the spin oscillator, we block the idler EPR beam and drive the atoms with a coherent state of light. The Larmor frequency is set to Ωa/2π ≈ 10.5 kHz and the quadrature of the output probe light is adjusted by a quarter-wave plate and a half-wave plate. In Extended Data Fig. 2b, the recorded quantum noise, dominated by the spin QBA noise is shown as the red area. Choosing an optimal polarization of detected light, we observe 5 dB of ponderomotive squeezing, as shown in the left inset. By fitting the shown spin noise spectra, we can extract both the narrowband and the broadband spin readout and decay rates, along with the losses after the spin ensemble and the effective thermal occupancies (see Extended Data Table 1). The total extracted occupancy number of approximately 3.5 is the result of two factors: the imperfect spin polarization (measured using the magneto-optical resonances) contributes about 1 and the technical noise sources contribute about 2.5 (for details, see Supplementary Information Section IIB). The effective thermal occupancies for the narrowband and broadband spin responses are the same. The reconstructed atomic thermal noise (the light-blue area) and broadband noise (the purple area) are also presented in Extended Data Fig. 2b. The impact of these distinct spectral features on the conditional frequency-dependent squeezing level is discussed below. The red area, representing the QBA noise, highlights the key quantum contribution that enables the frequency-dependent rotation of the squeezing phase. The same calibration procedure was applied to experimental data at 54 kHz Larmor frequency, demonstrated in Extended Data Fig. 2. The reduced classical noise at this frequency band allowed for better fitting.

After characterizing the spin oscillator, we unblock the idler output of the NOPO and record the dynamics of the spin oscillator driven by the idler component of the EPR field. The virtual rigidity phase δθi is extracted by fitting the noise spectrum shown in the right inset of Extended Data Fig. 2b (green trace). By combining the overall losses obtained from the EPR source calibration with the optical and detection losses after atoms evaluated from ponderomotive squeezing, we estimate the propagation efficiency between the NOPO and atoms to be ηi,in ≈ 89%. The optical losses from the atoms to the detection in the idler arm have been measured and result in the efficiency ηi,out ≈ 90%. Propagation efficiency from the NOPO and the detection efficiency in the signal arm result in ηs ≈ 92%. On the basis of those numbers, the predicted degree of two-mode squeezing fits the observed degree of squeezing as shown in Extended Data Fig. 2.

Using the parameters extracted from these independent calibrations and the model presented in the next sections, equation (10), we calculate the predicted frequency-dependent conditional squeezing as a function of the signal homodyne angle θs shown in Figs. 2 and 3. The figures show good agreement between the predicted spectra of quantum noise and the experimental data.

Phase control of the signal and idler fields

A feature of the EPR source critical for the present work is phase control of the two-colour EPR state. Here we describe its underlying principles and a complete report is in preparation. The phases of the signal and idler beams of the NOPO are related to the pump phase by θp = ϕi + ϕs (refs. 35,54). To precisely track the phase of the signal and the idler, we inject a coherent beam αc co-propagating with the pump and frequency-shifted by δωc from the 1,064-nm laser by two acousto-optic modulators.

In this experiment, we choose δωc/2π = 3 MHz, well inside the NOPO cavity bandwidth but also far from the resonance of the atomic spin oscillator. An electronic reference phase for the control beam ϕc is provided by driving the acousto-optic modulators by two outputs of an ultralow-phase-noise direct digital synthesizer.

The control beam experiences the parametric interaction and is amplified while maintaining its phase, resulting in the output field \({\alpha }_{{\rm{c}}}^{{\rm{s}}}\). The interaction of control and pump provides the simultaneous generation of another coherent field, \({\alpha }_{{\rm{c}}}^{{\rm{i}}}\), centred at frequency ωi − δωc. In this case, the field phase is the combination of the pump and signal control beam phases, \({\phi }_{{\rm{c}}}^{{\rm{i}}}={\theta }_{{\rm{p}}}-{\phi }_{{\rm{c}}}\). The classical beams generated by this process propagate together with their respective entangled fields to the homodyne detections. We demodulate the photocurrents using the electronic reference. This provides an error signal proportional to the phase difference between the entangled fields and the local oscillators, measured by the two homodyne detectors. The photocurrent from the homodyne detectors Is(t) contains the information from the signal-arm quadrature qs(θs) and the beat note of the local oscillator with the control field shifted from the relevant signal band by δωc

with the second term allowing us to select and set the homodyne LO phase θs. In turn, the outcome of the measurement of the idler field by means of the homodyne detection can be presented as

in which the first term is the idler quantum field contribution and the second term is the beat note between the second control field that has passed through the NOPO channel and the respective local oscillator. The demodulated signal at δωc/2π provides a tool to control the homodyne phase θi = ϕi + δθi, whereas the phase offset δθi can be tuned separately using the quarter-wave plate (see the set-up in Extended Data Fig. 1 and Fig. 1). An exact definition of Qi(θi) is given in the next section.

The frequency offset of δωc/2π ≃ 3 MHz guarantees that locking of those phases is not affected by the atomic spin oscillator. The procedure described above provides a set of well-defined phases that we use as references for the scan of θs involved in the demonstration of frequency-dependent conditional squeezing.

Idler field and light–atoms interaction

The 1.6-GHz detuning of the 852-nm NOPO idler field from atomic resonance is achieved by changing the frequency of the 1,064-nm laser, which alters the NOPO cavity length and its resonance condition. The 852-nm laser lock follows the change, enabling fine-tuning of the idler field with precision close to the NOPO cavity bandwidth.

To enable interaction between the idler field and the atomic spin ensemble, we overlap the idler output of the NOPO with an orthogonally polarized probe beam. This is realized by combining the linearly polarized idler and probe beams on a polarizing beam splitter, which transforms the quadrature fluctuations of the idler field into Stokes operator fluctuations55,56. For a linearly polarized, strong coherent probe beam with a relative phase ϕi between the idler and the probe, the quadratures map onto the Stokes operators as \({q}_{{\rm{i}}}({\phi }_{{\rm{i}}})=\sqrt{2}{{\mathcal{S}}}_{2}^{{\rm{in}}}/| {\alpha }_{{\rm{pr}}}| \) and \({q}_{{\rm{i}}}({\phi }_{{\rm{i}}}+\pi /2)=\sqrt{2}{{\mathcal{S}}}_{3}^{{\rm{in}}}/| {\alpha }_{{\rm{pr}}}| \), in which αpr is the amplitude of the probe field, \(\{{{\mathcal{S}}}_{0},{{\mathcal{S}}}_{1},{{\mathcal{S}}}_{2},{{\mathcal{S}}}_{3}\}\) are quantum Stokes operators obeying \([{{\mathcal{S}}}_{2},{{\mathcal{S}}}_{3}]=i{{\mathcal{S}}}_{1}\) (and cyclical permutations thereof) and \({q}_{{\rm{i}}}({\phi }_{{\rm{i}}})=\cos ({\phi }_{{\rm{i}}}){p}_{{\rm{i}}}+\sin ({\phi }_{{\rm{i}}}){x}_{{\rm{i}}}\) is the quadrature of the optical field entering the atomic ensemble.

The idler field encoded into the polarization state is processed by the atomic ensemble. The output Stokes parameters are then given by \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{2}^{{\rm{out}}}={{\mathcal{S}}}_{2}^{{\rm{in}}}+{{\mathcal{K}}}_{a}{{\mathcal{S}}}_{3}^{{\rm{in}}}+{{\mathcal{N}}}_{{\rm{a}}}\) and \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{3}^{{\rm{out}}}={{\mathcal{S}}}_{3}^{{\rm{in}}}\), in which \({{\mathcal{N}}}_{{\rm{a}}}={N}_{{\rm{a}}}| {\alpha }_{{\rm{pr}}}| /\sqrt{2}\); \({{\mathcal{K}}}_{{\rm{a}}}\) and Na are defined in the main text.

The light emerging from the spin ensemble is measured by the polarization homodyne detection. The diagonal linear and circular polarization operators \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{2}\) and \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{3}\) are measured by passing light through a half-wave plate and an extra quarter-wave plate, respectively, followed by the polarizing beam splitter, as shown in Extended Data Fig. 1. The resulting measured Stokes quadrature operator is \({{\mathcal{R}}}_{{\rm{i}}}(\delta {\theta }_{{\rm{i}}})={{\mathcal{S}}}_{2}^{{\rm{out}}}\cos (\delta {\theta }_{{\rm{i}}})+{{\mathcal{S}}}_{3}^{{\rm{out}}}\sin (\delta {\theta }_{{\rm{i}}})={Q}_{{\rm{i}}}(\delta {\theta }_{{\rm{i}}})| {\alpha }_{{\rm{pr}}}| /\sqrt{2}\), in which the phase δθi is set by the orientation of the quarter-wave plate.

The phase ϕi is set by a coherent control loop that monitors the phase offset between the probe beam and the control field at the idler homodyne detector. The control field follows the same propagation path as the idler beam but is unaffected by the atomic oscillator owing to a frequency offset, δωc. The phase offset ϕi measured by the coherent control loop combines the encoding phase and δθi.

Throughout those measurements, we set θi = 0, so that the quadrature of the idler detected outside the bandwidth of the spin dynamics bandwidth (Ω ≫ |Ωa|) is pi. In the setting not engaging virtual rigidity, that is, in the absence of a quarter-wave plate (δθi = 0), the coherent control loop sets the encoding phase ϕi = 0, corresponding to \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{2}^{{\rm{in}}}={p}_{{\rm{i}}}| {\alpha }_{{\rm{pr}}}| /\sqrt{2}\) and \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{3}^{{\rm{in}}}={x}_{{\rm{i}}}| {\alpha }_{{\rm{pr}}}| /\sqrt{2}\). With such settings, the final idler photocurrent within the relevant range of frequencies Ω is proportional to \({P}_{{\rm{i}}}={p}_{{\rm{i}}}+{{\mathcal{K}}}_{{\rm{a}}}(\varOmega ){x}_{{\rm{i}}}+{N}_{{\rm{a}}}(\varOmega )\). For general δθi, we have Qi(δθi) = Xisin(δθi) + Picos(δθi).

Optimal quantum noise reduction by Wiener filtering in the idler channel

The squeezing we demonstrate for the signal arm is conditioned on the idler-arm measurement

To achieve the maximal frequency-dependent squeezing of the signal field based on the idler measurement record, a Wiener filter g(Ω, θs, δθi) is designed for each detection phase θs, which provides an optimal estimate of the correlated quantum noise in the idler channel. By subtracting the filtered idler quantum noise from the signal noise, the optimal reduction of the signal quantum noise limited by the remaining uncorrelated noise is achieved11,31,57.

Our protocol is compatible with both causal and non-causal filtering g(Ω, θs, δθi) of the idler measurement record. Causal filtering, which uses only past idler measurements to reduce the signal-arm noise at a given time, is required for using the sensor for, for example, real-time signal tracking or adaptive sensing. On the other hand, the non-causal filtering uses the full idler measurement record and is relevant for sensing scenarios in which the signal is extracted by post-processing of the full measurement record.

In this work, we focus on non-causal conditioning, thereby emphasizing the maximally achievable squeezing. In this case, the optimal gain is given by the idler spectral density \({S}_{{Q}_{{\rm{i}}}}\) and the cross-spectral density \({S}_{{q}_{{\rm{s}}},{Q}_{{\rm{i}}}}\) of the two entangled channels as

which leads to the power spectral density of the optimized signal

The optimal filter (equation (8)) automatically takes into account the signal homodyne detection phase θs, deleterious noise introduced in the idler path and phase shifts as a result of the atomic dissipation through decoherence, as represented by the complexity of the response function \({{\mathcal{K}}}_{{\rm{a}}}(\varOmega )\) (see equation (2)). Furthermore, the Wiener filter can potentially compensate for imperfect matching between the idler and the quantum sensor response introduced in the signal arm in a particular sensing application. The analysis of the experimental data using this approach is detailed in Supplementary Information Section II.

Theory of frequency-dependent conditional squeezing

Figures 2 and 3 present comparisons of the measured squeezing with the theoretical model, which we describe here. The model consists of equations of motion of the spin oscillator and input–output relations describing its interaction with light. It accounts for contributions of thermal and broadband noise to the response of the spin system, as well as for the effects of imperfect readout efficiency (ηi,out < 1), imperfect coupling of the idler beam to the oscillator (ηi,in < 1) and the readout efficiency in the signal arm, ηs < 1. From this model, we obtain an expression for the power spectral density of the conditioned signal photocurrent Qs|i, which, in turn, is minimized using Wiener filter theory as outlined in the preceding subsection. Detailed calculations are provided in Supplementary Information Section IC.

Here we present a general formula for an arbitrary phase offset δθi imposed by the quarter-wave plate and giving rise to virtual rigidity. The case of no virtual rigidity can be obtained by setting δθi = 0. The spectrum of the optimally conditioned signal, normalized to the signal shot noise SSN level, in the signal-arm detection quadrature θs is given by

in which dependencies on Ω are omitted for brevity. The numerator of the second term in the brackets represents the correlation between the signal and idler, shaped by the backaction of the atomic spin oscillator. The denominator captures the spectrum of the idler signal, incorporating, as well as the backaction, the following four terms, responsible for the various deleterious effects mentioned above:

In order of appearance, they represent the effects of suboptimal coupling of the idler field to the spin ensemble, ηi,in, imperfect readout efficiency of the idler detector, ηi,out, thermal occupation of the collective spin state, nth, governed by \({{\mathcal{K}}}_{{\rm{th}}}(\varOmega )=\sqrt{2{\gamma }_{{\rm{a}}}{\varGamma }_{{\rm{a}}}}{\varOmega }_{{\rm{a}}}/({\varOmega }_{{\rm{a}}}^{2}-{\varOmega }^{2}-i{\gamma }_{{\rm{a}}}\varOmega \,+\)\({\gamma }_{{\rm{a}}}^{2}/4)\) and the broadband noise occupation number, nbb, governed by \({{\mathcal{K}}}_{{\rm{bb}}}(\varOmega )=\sqrt{2{\gamma }_{{\rm{bb}}}{\varGamma }_{{\rm{bb}}}}{\varOmega }_{{\rm{a}}}/({\varOmega }_{{\rm{a}}}^{2}-{\varOmega }^{2}-i{\gamma }_{{\rm{bb}}}\varOmega +{\gamma }_{{\rm{bb}}}^{2}/4)\). The effect of the virtual rigidity is captured by the gain

The effective backaction \({{\mathcal{K}}}_{{\rm{a}}}^{{\rm{eff}}}(\varOmega )\equiv {{\mathcal{K}}}_{{\rm{a}}}(\varOmega ,{\varOmega }_{{\rm{a}}}^{{\rm{eff}}},{\varGamma }_{{\rm{a}}}^{{\rm{eff}}})\) is defined as the backaction coefficient used in equation (2) but evaluated with the effective readout rate and the effective Larmor frequency

these expressions are valid insofar as the quantity appearing under the square roots is positive, as is the case for our system parameters.

By minimizing equation (10) as a function of θs for each Fourier component Ω separately, we find the optimal angle θs = ΦVR(Ω) to be the solution to the set of equations

In the limit \({\gamma }_{{\rm{a}}}^{2}\ll {({\varOmega }_{{\rm{a}}}^{{\rm{eff}}})}^{2},{({\varGamma }_{{\rm{a}}}^{{\rm{eff}}})}^{2}\), we have \({| {({{\mathcal{K}}}_{{\rm{a}}}^{{\rm{eff}}}(\varOmega ))}^{-1}| }^{2}\approx {{\rm{Re}}}^{2}[{({{\mathcal{K}}}_{{\rm{a}}}^{{\rm{eff}}}(\varOmega ))}^{-1}]\) \(\approx \,{[{({{\mathcal{K}}}_{{\rm{a}}}^{{\rm{eff}}}(\varOmega ))}^{-1}]}_{{\gamma }_{{\rm{a}}}\to 0}^{2}\), in which equations 18a and 18b reduce to

as presented in the main text. This expression, valid for general δθi, is used to generate the dashed curves presented as Φj(Ω) in Figs. 2b and 3b,d,f for the various special cases labelled j ∈ {±, VR}. Evaluating equation (10) at θs = ΦVR(Ω) yields the achieved degree of (frequency-dependent) squeezing; this amounts to replacing the factor

in which the approximation is valid in the limit \({\gamma }_{{\rm{a}}}^{2}\ll {({\varOmega }_{{\rm{a}}}^{{\rm{eff}}})}^{2},{({\varGamma }_{{\rm{a}}}^{{\rm{eff}}})}^{2}\).

In the aforementioned limit, we may use equations (2) and (19) to derive an expression for the bandwidth δΩSQL > 0 over which the rotation angle Φ(Ω) (∈[0, π] for specificity) changes by 45° relative to its value at the effective spin oscillator resonance \(\varPhi ({\varOmega }_{{\rm{a}}}^{{\rm{eff}}})=\pi /2\), that is, it obeys \(| \varPhi ({\varOmega }_{{\rm{a}}}^{{\rm{eff}}}+\delta {\varOmega }_{{\rm{SQL}}})-\varPhi ({\varOmega }_{{\rm{a}}}^{{\rm{eff}}})| =\pi /4\). The result is \(\delta {\varOmega }_{{\rm{SQL}}}=| {\varOmega }_{{\rm{a}}}^{{\rm{eff}}}| \)\((\sqrt{1+{\varGamma }_{{\rm{a}}}^{{\rm{eff}}}/| {\varOmega }_{{\rm{a}}}^{{\rm{eff}}}| }-1)\approx {\varGamma }_{{\rm{a}}}^{{\rm{eff}}}/2\), in which the approximation holds under the extra assumption \({\varGamma }_{{\rm{a}}}^{{\rm{eff}}}\ll | {\varOmega }_{{\rm{a}}}^{{\rm{eff}}}| \).

As well as comparing our model with the squeezing achieved in the present experiment, we also used the model to predict the degree of broadband noise reduction obtained by reducing the two main imperfections of our system: broadband spin noise and thermal spin noise. The results are reported in Extended Data Fig. 3 and further details can be found in Supplementary Information Section IIB.

Data availability

The data and code supporting the findings of this study are deposited in the University of Copenhagen depository at https://erda.ku.dk/archives/d33b4254d5a426c28056ee54da7a776c/published-archive.html.

References

Tebbenjohanns, F. et al. Quantum control of a nanoparticle optically levitated in cryogenic free space. Nature 595, 378–382 (2021).

Purdy, T. P., Peterson, R. W. & Regal, C. A. Observation of radiation pressure shot noise on a macroscopic object. Science 339, 801–804 (2013).

Acernese, F. et al. Quantum backaction on kg-scale mirrors: observation of radiation pressure noise in the advanced Virgo detector. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 131101 (2020).

Yu, H. et al. Quantum correlations between light and the kilogram-mass mirrors of LIGO. Nature 583, 43–47 (2020).

Youssefi, A. et al. A squeezed mechanical oscillator with millisecond quantum decoherence. Nat. Phys. 19, 1697–1702 (2023).

Murch, K. W. et al. Observation of quantum-measurement backaction with an ultracold atomic gas. Nat. Phys. 4, 561–564 (2008).

Bohnet, J. G. et al. Reduced spin measurement back-action for a phase sensitivity ten times beyond the standard quantum limit. Nat. Photon. 8, 731–736 (2014).

Caves, C. M. et al. On the measurement of a weak classical force coupled to a quantum-mechanical oscillator. I. Issues of principle. Rev. Mod. Phys. 52, 341–392 (1980).

Braginsky, V. B. & Khalili, F. Y. Quantum nondemolition measurements: the route from toys to tools. Rev. Mod. Phys. 68, 1 (1996).

Chen, Y. Macroscopic quantum mechanics: theory and experimental concepts of optomechanics. J. Phys. B. At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 46, 104001 (2013).

Danilishin, S. L., Khalili, F. Y. & Miao, H. Advanced quantum techniques for future gravitational-wave detectors. Living Rev. Relativ. 22, 2 (2019).

Aslam, N. et al. Quantum sensors for biomedical applications. Nat. Rev. Phys. 5, 157–169 (2023).

Bass, S. D. & Doser, M. Quantum sensing for particle physics. Nat. Rev. Phys. 6, 329–339 (2024).

Aspelmeyer, M., Kippenberg, T. J. & Marquardt, F. Cavity optomechanics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 86, 1391–1452 (2014).

Julsgaard, B., Kozhekin, A. & Polzik, E. S. Experimental long-lived entanglement of two macroscopic objects. Nature 413, 400–403 (2001).

Hammerer, K. et al. Establishing Einstein-Poldosky-Rosen channels between nanomechanics and Atomic ensembles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 020501 (2009).

Tsang, M. & Caves, C. M. Coherent quantum-noise cancellation for optomechanical sensors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 123601 (2010).

Tsang, M. & Caves, C. M. Evading quantum mechanics: engineering a classical subsystem within a quantum environment. Phys. Rev. X 2, 031016 (2012).

Møller, C. B. et al. Quantum back-action-evading measurement of motion in a negative mass reference frame. Nature 547, 191–195 (2017).

Thomas, R. A. et al. Entanglement between distant macroscopic mechanical and spin systems. Nat. Phys. 17, 228–233 (2021).

Mercier de Lépinay, L. et al. Quantum mechanics-free subsystem with mechanical oscillators. Science 372, 625–629 (2021).

Kampel, N. S. et al. Improving broadband displacement detection with quantum correlations. Phys. Rev. X 7, 021008 (2017).

Mason, D. et al. Continuous force and displacement measurement below the standard quantum limit. Nat. Phys. 15, 745–749 (2019).

Khalili, F. Y. & Polzik, E. S. Overcoming the standard quantum limit in gravitational wave detectors using spin systems with a negative effective mass. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 031101 (2018).

Zeuthen, E., Polzik, E. S. & Khalili, F. Y. Gravitational wave detection beyond the standard quantum limit using a negative-mass spin system and virtual rigidity. Phys. Rev. D 100, 062004 (2019).

Ganapathy, D. et al. Broadband quantum enhancement of the LIGO detectors with frequency-dependent squeezing. Phys. Rev. X 13, 041021 (2023).

Acernese, F. et al. Frequency-dependent squeezed vacuum source for the Advanced Virgo gravitational-wave detector. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 041403 (2023).

Jia, W. et al. Squeezing the quantum noise of a gravitational-wave detector below the standard quantum limit. Science 385, 1318–1321 (2024).

Kimble, H. J. et al. Conversion of conventional gravitational-wave interferometers into quantum nondemolition interferometers by modifying their input and/or output optics. Phys. Rev. D 65, 022002 (2001).

Jones, P. et al. Implications of the quantum noise target for the Einstein Telescope infrastructure design. Phys. Rev. D 101, 082002 (2020).

Ma, Y. et al. Proposal for gravitational-wave detection beyond the standard quantum limit through EPR entanglement. Nat. Phys. 13, 776–780 (2017).

Nishino, Y. et al. Frequency-dependent squeezing for gravitational-wave detection through quantum teleportation. Phys. Rev. A 110, 022601 (2024).

Brown, D. D. et al. Broadband sensitivity enhancement of detuned dual-recycled Michelson interferometers with EPR entanglement. Phys. Rev. D 96, 062003 (2017).

Peng, X. et al. Approaches of frequency-dependent squeezing for the low frequency detector of the Einstein Telescope. Phys. Rev. D 110, 082006 (2024).

Reid, M. D. Demonstration of the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen paradox using nondegenerate parametric amplification. Phys. Rev. A 40, 913–923 (1989).

Jia, J. et al. Acoustic frequency atomic spin oscillator in the quantum regime. Nat. Commun. 14, 6396 (2023).

Borregaard, J., Davis, E., Bentsen, G. S., Schleier-Smith, M. H. & Sørensen, A. S. One-and two-axis squeezing of atomic ensembles in optical cavities. New J. Phys. 19, 093021 (2017).

Kitagawa, M. & Ueda, M. Squeezed spin states. Phys. Rev. A 47, 5138 (1993).

Bergman, K. & Haus, H. A. Squeezing in fibers with optical pulses. Opt. Lett. 16, 663–665 (1991).

Danilishin, S. L. & Khalili, F. Y. Quantum measurement theory in gravitational-wave detectors. Living Rev. Relativ. 15, 5 (2012).

Brasil, T. B. et al. Two-colour high-purity Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen photonic state. Nat. Commun. 13, 4815 (2022).

McCuller, L. et al. Frequency-dependent squeezing for advanced LIGO. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 171102 (2020).

Buonanno, A. & Chen, Y. Quantum noise in second generation, signal-recycled laser interferometric gravitational-wave detectors. Phys. Rev. D 64, 042006 (2001).

Gonzalez-Ballestero, C. et al. Suppressing recoil heating in levitated optomechanics using squeezed light. PRX Quantum 4, 030331 (2023).

Yap, M. J. et al. Broadband reduction of quantum radiation pressure noise via squeezed light injection. Nat. Photon. 14, 19–23 (2020).

Julsgaard, B., Sherson, J., Cirac, J. I., Fiurášek, J. & Polzik, E. S. Experimental demonstration of quantum memory for light. Nature 432, 482–486 (2004).

Jensen, K. et al. Quantum memory for entangled continuous-variable states. Nat. Phys. 7, 13–16 (2010).

Dias, J. et al. Quantum repeater for continuous-variable entanglement distribution. Phys. Rev. A 102, 052425 (2020).

Hammerer, K., Sørensen, A. S. & Polzik, E. S. Quantum interface between light and atomic ensembles. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 1041–1093 (2010).

Kimble, H. J. The quantum internet. Nature 453, 1023–1030 (2008).

Wehner, S., Elkouss, D. & Hanson, R. Quantum internet: a vision for the road ahead. Science 362, eaam9288 (2018).

Borregaard, J. et al. Scalable photonic network architecture based on motional averaging in room temperature gas. Nat. Commun. 7, 11356 (2016).

Shaham, R., Katz, O. & Firstenberg, O. Quantum dynamics of collective spin states in a thermal gas. Phys. Rev. A 102, 012822 (2020).

Schori, C., Sørensen, J. L. & Polzik, E. S. Narrow-band frequency tunable light source of continuous quadrature entanglement. Phys. Rev. A 66, 033802 (2002).

Luis, A. & Korolkova, N. Polarization squeezing and nonclassical properties of light. Phys. Rev. A 74, 043817 (2006).

Bowen, W. P. et al. Polarization squeezing of continuous variable Stokes parameters. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 093601 (2002).

Gould, D. W. et al. Optimal quantum noise cancellation with an entangled witness channel. Phys. Rev. Res. 3, 043079 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work has been supported by Villum Fonden under a Villum Investigator Grant, no. 25880, by the Novo Nordisk Foundation through Copenhagen Center for Biomedical Quantum Sensing, grant number NNF24SA0088433 and through ‘Quantum for Life’ Center, grant no. NNF20OC0059939, by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement nos. 101149150 ‘EPROXY’ and 101060955 QNOIWA and the European Research Council Advanced grant QUANTUM-N. We acknowledge A. Zoumis and R. Yde for their experimental contributions, F. Khalili for insightful discussions and careful reading of the manuscript and valuable discussions with J. Appel, M. Lassen, R. Thomas and M. Parniak at the early stages of this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.J. and M. Bocoum developed the atomic spin oscillator set-up. T.B.B. designed the two-colour EPR source and built it together with V.N. and A.G. V.N., J.J., T.B.B., A.G. and M. Bocoum performed the data acquisition. E.Z., V.N., J.J. and A.G. developed the analytical model. J.J. and V.N. performed the data analysis. M. Balabas fabricated the caesium cell. J.H.M. contributed valuable discussions. T.B.B. led the experimental work. E.S.P. conceived and led the project. All authors contributed to writing the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Nils Engelsen and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Experimental set-up main components.

The experimental set-up includes two lasers: a 1,064-nm continuous-wave laser and a tunable continuous-wave Ti:sapphire laser at 852 nm. The two-colour EPR state set-up involves two nonlinear optical interactions: sum-frequency generation (SFG) and a NOPO. The 1,064-nm and 852-nm lasers produce the SFG light in a nonlinear crystal, which serves as the pump for the NOPO with pump phase θp. The NOPO generates the EPR state at 1,064 nm (signal) and 852 nm (idler), represented by dashed lines. The signal and idler beams are separated by a dichroic mirror. The signal is directed to balanced homodyne detection (HDs) with local oscillator phase θs, whereas the idler is mixed with the probe beam at a polarizing beam splitter (PBS) with relative phase ϕi and propagates in free space (approximately 10 m) to the atomic oscillator set-up. The probe–idler spatial profile is modified to a square top-hat beam by a top-hat shaper (THS) before being sent to the caesium (Cs) vapour cell. The cell is placed inside a magnetic shield with a set of coils controlling the bias magnetic field. The optical pump system prepares the spin ensemble in a highly polarized state. After interaction, the idler quantum state is sent to polarization homodyne detection (HDi), for which a quarter-wave plate (QWP) and a half-wave plate (HWP) determine the phase shift δθi. A part of the 1,064-nm laser is frequency-shifted by 3 MHz to produce the coherent-lock field (CLF) beam injected to the NOPO with phase ϕc, which provides the phase reference for the detection system and feedback control of the detected quadratures. The fields for the local oscillators LOs and LOi are produced by the 1,064-nm and 852-nm lasers, respectively. Each LO is filtered by a mode-cleaner cavity (not shown). Both photocurrents from the homodyne detectors are sent to a data acquisition (DAQ) system for recording and post-processing. The quadrature correlations at specific sideband frequencies for different set phases (ϕi + δθi, θs) are used to demonstrate the frequency-dependent conditional squeezing. The phases ϕi and θs are actively stabilized to fix the quadrature detection in relation to the pump phase θp.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Calibration of the hybrid quantum system.

a, Quantum noise of light fields in the absence of the atomic spin oscillator. Teal trace, total shot noise of the signal and idler. Grey trace, shot noise of the signal. Blue trace shows 3.2 dB of conditional, frequency-independent EPR squeezing. It corresponds to ≃6 dB of entanglement of the EPR state when normalized to the total shot noise of the signal and idler fields (teal trace). Orange trace, signal-arm EPR fluctuations. b, Idler-arm noise spectra in the presence of the atomic spin oscillator. Main panel, atoms driven by vacuum fluctuations; the reconstructed quantum-backaction noise (QBAN, red area), the decoherence-associated spin thermal (TH, light-blue area) and broadband noise (BB, purple area) are shown. Left inset, ponderomotive squeezing of light by atoms observed for two different idler detection angles δθi. Right inset, atoms driven by EPR fluctuations, with (teal) and without (red) the virtual rigidity (VR) effect. Dashed curves are theoretical fits (see Methods for details). All traces are normalized to the idler shot noise.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Demonstration of overall quantum noise reduction with potential improvements to the spin oscillator.

a,b, Red (positive mass; a) and blue (negative mass; b) points show the measured minimal conditional squeezing at each signal phase, along with the overall modelled quantum noise reduction based on the calibrated parameters of the present spin system. The discrepancy between theoretical predictions and experimental data at frequencies below 5 kHz is attributed to residual laser amplitude noise. Estimated conditional squeezing level are also presented for two scenarios: when the atomic thermal (TH) occupation is reduced by a factor of 3 (purple curve) and when the atomic broadband (BB) readout rate is reduced by a factor of 6 (teal curve) relative to present conditions. With both noise sources reduced, the optimal spin system generates the conditional frequency-dependent squeezing (FDS) (red/blue dashed lines), limited only by the frequency-independent level of squeezing of light (light-blue trace).

Extended Data Fig. 4 Uncertainty analysis for frequency-dependent conditional squeezing by means of an effective positive-mass oscillator Ωa/2π = 10.7 kHz at different signal homodyne detection phases (10 out of 18).

a, The solid lines represent the inferred quantum noise on the signal detector conditioned on the idler measurement, with the shaded regions indicating the 1σ uncertainty (68% confidence interval). The dashed lines show the quantum noise model fitted to the measured data using a χ2 method. b, The residuals between the measured data and the fitted model, normalized to 1σ uncertainty, are plotted. Noise spikes near 20 kHz (attributed to the etalon dither lock of the 852-nm laser) and classical noise (from both laser intensity noise and magnetic noise sources) at low acoustic frequency (below 10 kHz) are clearly visible in the residual plots.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Uncertainty analysis for frequency-dependent conditional squeezing by means of an effective negative-mass oscillator Ωa/2π = −10.5 kHz at different signal homodyne detection phases (10 out of 18).

a, The solid lines represent the inferred quantum noise on the signal detector conditioned on the idler measurement, with the shaded regions indicating the 1σ uncertainty (68% confidence interval). The dashed lines show the quantum noise model fitted to the measured data using a χ2 method. b, The residuals between the measured data and model fit, normalized to 1σ uncertainty.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Sections 1–3, including Supplementary Figs. 1–3 – see Contents for details.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Novikov, V., Jia, J., Brasil, T.B. et al. Hybrid quantum network for sensing in the acoustic frequency range. Nature 643, 955–960 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09224-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09224-3

This article is cited by

-

Sub-shot-noise Rydberg EIT spectrum

PhotoniX (2025)