Abstract

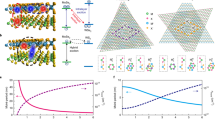

Two-dimensional moiré materials are formed by artificially stacking atomically thin monolayers. Correlated and topological quantum phases can be engineered by precise choice of stacking geometry1,2,3. These designer electronic properties depend crucially on interlayer coupling and atomic registry4,5. An open question is how the atomic registry responds on ultrafast timescales to optical excitation and whether the moiré geometry can be dynamically reconfigured to tune emergent phenomena in real time. Here we show that femtosecond photoexcitation drives a coherent twist–untwist motion of the moiré superlattice in 2° and 57° twisted WSe2/MoSe2 heterobilayers, resolved directly by ultrafast electron diffraction. On above-band-gap photoexcitation, the moiré superlattice diffraction features are enhanced within 1 ps and subsequently suppressed several picoseconds after, deviating markedly from typical photoinduced lattice heating. Kinetic diffraction analysis, supported by simulations of the sample dynamics, indicates a peak-to-trough local twist angle modulation of 0.6°, correlated with a sub-THz frequency moiré phonon. This motion is driven by ultrafast charge transfer that transiently increases interlayer attraction. Our results could lead to ultrafast control of moiré periodic lattice distortions and, by extension, the local moiré potential that shapes excitons, polarons and correlation-driven behaviours.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The experimental data supporting the conclusions of this article can be found in the figures. The data points that constitute the main experimental result, Fig. 2a,b,d,e, are tabulated in .csv files and are available online. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Simulation input files associated with the construction of twisted heterobilayer structures, atomic relaxation, phonon calculations, electronic structures and deformation potentials are available at GitHub (https://github.com/imaitygit/PaperData/tree/main/PhotoinducedTwist).

References

Cao, Y. et al. Correlated insulator behaviour at half-filling in magic-angle graphene superlattices. Nature 556, 80–84 (2018).

Regan, E. C. et al. Mott and generalized Wigner crystal states in WSe2/WS2 moiré superlattices. Nature 579, 359–363 (2020).

Xia, Y. et al. Superconductivity in twisted bilayer WSe2. Nature 637, 833–838 (2025).

Yoo, H. et al. Atomic and electronic reconstruction at the van der Waals interface in twisted bilayer graphene. Nat. Mater. 18, 448–453 (2019).

Xie, H. et al. Twist engineering of the two-dimensional magnetism in double bilayer chromium triiodide homostructures. Nat. Phys. 18, 30–36 (2022).

Wang, L. et al. Correlated electronic phases in twisted bilayer transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Mater. 19, 861–866 (2020).

Shimazaki, Y. et al. Strongly correlated electrons and hybrid excitons in a moiré heterostructure. Nature 580, 472–477 (2020).

Park, H. et al. Observation of fractionally quantized anomalous Hall effect. Nature 622, 74–79 (2023).

Li, H. et al. Imaging two-dimensional generalized Wigner crystals. Nature 597, 650–654 (2021).

Zhou, Y. et al. Bilayer Wigner crystals in a transition metal dichalcogenide heterostructure. Nature 595, 48–52 (2021).

Guo, Y. et al. Superconductivity in 5.0° twisted bilayer WSe2. Nature 637, 839–845 (2025).

Carr, S., Fang, S. & Kaxiras, E. Electronic-structure methods for twisted moiré layers. Nat. Rev. Mater. 5, 748–763 (2020).

Maity, I., Maiti, P. K., Krishnamurthy, H. & Jain, M. Reconstruction of moiré lattices in twisted transition metal dichalcogenide bilayers. Phys. Rev. B 103, L121102 (2021).

Nam, N. N. & Koshino, M. Lattice relaxation and energy band modulation in twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 96, 075311 (2017).

Wang, C. et al. Fractional Chern insulator in twisted bilayer MoTe2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 036501 (2024).

Zhang, X.-W. et al. Polarization-driven band topology evolution in twisted MoTe2 and WSe2. Nat. Commun. 15, 4223 (2024).

Seyler, K. L. et al. Signatures of moiré-trapped valley excitons in MoSe2/WSe2 heterobilayers. Nature 567, 66–70 (2019).

Tran, K. et al. Evidence for moiré excitons in van der Waals heterostructures. Nature 567, 71–75 (2019).

Jin, C. et al. Observation of moiré excitons in WSe2/WS2 heterostructure superlattices. Nature 567, 76–80 (2019).

Alexeev, E. M. et al. Resonantly hybridized excitons in moiré superlattices in van der Waals heterostructures. Nature 567, 81–86 (2019).

Campbell, A. J. et al. Exciton-polarons in the presence of strongly correlated electronic states in a MoSe2/WSe2 moiré superlattice. NPJ 2D Mater. Appl. 6, 79 (2022).

Arsenault, E. A. et al. Two-dimensional moiré polaronic electron crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 126501 (2024).

Biswas, S. et al. Exciton polaron formation and hot-carrier relaxation in rigid Dion–Jacobson-type two-dimensional perovskites. Nat. Mater. 23, 937–943 (2024).

Dai, Z., Lian, C., Lafuente-Bartolome, J. & Giustino, F. Excitonic polarons and self-trapped excitons from first-principles exciton-phonon couplings. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 036902 (2024).

Barré, E. et al. Optical absorption of interlayer excitons in transition-metal dichalcogenide heterostructures. Science 376, 406–410 (2022).

Liu, F. et al. Disassembling 2D van der Waals crystals into macroscopic monolayers and reassembling into artificial lattices. Science 367, 903–906 (2020).

Duncan, C. J. R. et al. Multi-scale time-resolved electron diffraction: a case study in moiré materials. Ultramicroscopy 253, 113771 (2023).

Qiu, W., Zhang, B., Sun, Y., He, L. & Ni, Y. Atomic reconstruction enabled coupling between interlayer distance and twist in van der Waals bilayers. Extreme Mech. Lett. 69, 102159 (2024).

Tang, Y. et al. Simulation of Hubbard model physics in WSe2/WS2 moiré superlattices. Nature 579, 353–358 (2020).

Wang, T., Sun, H., Li, X. & Zhang, L. Chiral phonons: prediction, verification, and application. Nano Lett. 24, 4311–4318 (2024).

Li, W. H. et al. A kiloelectron-volt ultrafast electron micro-diffraction apparatus using low emittance semiconductor photocathodes. Struct. Dyn. 9, 024302 (2022).

Carr, S. et al. Relaxation and domain formation in incommensurate two-dimensional heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B 98, 224102 (2018).

Rosenberger, M. R. et al. Twist angle-dependent atomic reconstruction and moiré patterns in transition metal dichalcogenide heterostructures. ACS Nano 14, 4550–4558 (2020).

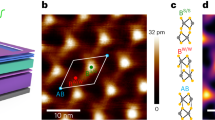

Sung, S. H. et al. Torsional periodic lattice distortions and diffraction of twisted 2D materials. Nat. Commun. 13, 7826 (2022).

Britt, T. L. et al. Direct view of phonon dynamics in atomically thin MoS2. Nano Lett. 22, 4718–4724 (2022).

Sood, A. et al. Bidirectional phonon emission in two-dimensional heterostructures triggered by ultrafast charge transfer. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 29–35 (2023).

Johnson, A. C. et al. Hidden phonon highways promote photoinduced interlayer energy transfer in twisted transition metal dichalcogenide heterostructures. Sci. Adv. 10, 8819 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Optical generation of high carrier densities in 2D semiconductor heterobilayers. Sci. Adv. 5, eaax0145 (2019).

Li, C. et al. Coherent phonons in van der Waals MoSe2/WSe2 heterobilayers. Nano Lett. 23, 8186–8193 (2023).

Mannebach, E. M. et al. Dynamic optical tuning of interlayer interactions in the transition metal dichalcogenides. Nano Lett. 17, 7761–7766 (2017).

Zhu, H. et al. Interfacial charge transfer circumventing momentum mismatch at two-dimensional van der Waals heterojunctions. Nano Lett. 17, 3591–3598 (2017).

Ji, Z. et al. Robust stacking-independent ultrafast charge transfer in MoS2/WS2 bilayers. ACS Nano 11, 12020–12026 (2017).

Gillen, R. & Maultzsch, J. Interlayer excitons in MoSe2/WSe2 heterostructures from first principles. Phys. Rev. B 97, 165306 (2018).

Thomsen, C., Grahn, H. T., Maris, H. J. & Tauc, J. Surface generation and detection of phonons by picosecond light pulses. Phys. Rev. B 34, 4129–4138 (1986).

Schmitt, D. et al. Formation of moiré interlayer excitons in space and time. Nature 608, 499–503 (2022).

Karni, O. et al. Structure of the moiré exciton captured by imaging its electron and hole. Nature 603, 247–252 (2022).

Wu, F., Lovorn, T., Tutuc, E. & MacDonald, A. H. Hubbard model physics in transition metal dichalcogenide moiré bands. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 026402 (2018).

Geng, W. T. et al. Displacement vorticity as the origin of moiré potentials in twisted WSe2/MoSe2 bilayers. Matter 6, 493–505 (2023).

Kim, S., Mendez-Valderrama, J. F., Wang, X. & Chowdhury, D. Theory of correlated insulators and superconductor at ν = 1 in twisted WSe2. Nat. Commun. 16, 1701 (2025).

Qian, C. et al. Lasing of moiré trapped MoSe2/WSe2 interlayer excitons coupled to a nanocavity. Sci. Adv. 10, eadk6359 (2024).

Schneider, G. F., Calado, V. E., Zandbergen, H., Vandersypen, L. M. & Dekker, C. Wedging transfer of nanostructures. Nano Lett. 10, 1912–1916 (2010).

Jiang, J.-W. & Zhou, Y.-P. (eds) Handbook of Stillinger-Weber Potential Parameters for Two-Dimensional Atomic Crystals (InTech, 2017).

Naik, M. H., Maity, I., Maiti, P. K. & Jain, M. Kolmogorov–Crespi potential for multilayer transition-metal dichalcogenides: capturing structural transformations in moiré superlattices. J. Phys. Chem. C 123, 9770–9778 (2019).

Thompson, A. P. et al. LAMMPS - a flexible simulation tool for particle-based materials modeling at the atomic, meso, and continuum scales. Comput. Phys. Commun. 271, 108171 (2022).

Naik, S., Naik, M. H., Maity, I. & Jain, M. Twister: construction and structural relaxation of commensurate moiré superlattices. Comput. Phys. Commun. 271, 108184 (2022).

Togo, A. & Tanaka, I. First principles phonon calculations in materials science. Scr. Mater. 108, 1–5 (2015).

Hu, J., Xiang, Y., Ferrari, B. M., Scalise, E. & Vanacore, G. M. Indirect exciton–phonon dynamics in MoS2 revealed by ultrafast electron diffraction. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2206395 (2023).

González-Manteiga, W. & Crujeiras, R. M. An updated review of goodness-of-fit tests for regression models. Test 22, 361–411 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The UED measurements and instrumentation were supported by the US Department of Energy (award nos. DE-SC0020144 and DE-SC0017631) and the US National Science Foundation (grant no. PHY-1549132), the Center for Bright Beams. Preparation of monolayers and twisted heterobilayers at Stanford University is supported by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency under agreement no. HR00112390108. F.L. acknowledges support from the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, CPIMS Program, under award no. DE-SC0026181. A.M.L. acknowledges support from the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, Materials Sciences and Engineering Division, under contract no. DE-AC02-76SF00515. The EMPAD detector deployment in this experiment was funded in part by the Kavli Institute at Cornell University. We are grateful to X.-Y. Zhu for his support and guidance in facilitating the TR-ARPES measurements conducted using the setup in his lab at Columbia University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.J.R.D., A.M.L., J.M.M. and F.L. conceived the high-Q-magnification UED experiment. A.M.L., J.M.M. and F.L. supervised the project. C.J.R.D., M.G., A.C.B. and M.K. performed the UED measurements. C.J.R.D. and A.C.B. analysed the UED data to generate the plots shown in Fig. 2. C.J.R.D., A.C.B., M.K., W.H.L., M.B.A., C.A.P., I.V.B. and J.M.M. built the UED setup. M.W.T., D.A.M., J.T.-L. and S.M.G. built and supported the EMPAD direct electron detector. A.C.J. prepared the samples and performed low-frequency Raman measurements with the support of F.L.; I.M. simulated the WSe2/MoSe2 phonon spectrum with the support of A.R. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the writing of the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Titus Neupert and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Pump-probe diffraction snapshots of WSe2/MoSe2.

(a) 2° WSe2/MoSe2 at a 1 ps pump-probe delay, showing the change in diffraction intensity. Direct image is shown inset. (b) 57° WSe2/MoSe2 at a 1 ps pump-probe delay, showing the change in diffraction intensity. Direct image is shown inset.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Second harmonic generation polarization scan.

Second harmonic generation (SHG) polarization scan on the 2° (a) and 57° (b) WSe2/MoSe2 heterobilayers used in UED measurements. The alignment of crystal axes in the two layers are determined by constructive and destructive interference. The SHG signals are excited using a 1030 nm femtosecond laser with < 200 fs pulse duration at room temperature, and captured by an EM CCD detector.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Power spectral density of UED time series.

Spectra are computed as the square modulus of the discrete Fourier transform (DFT) and normalized so that the maximum value is unity. No detrending is applied. (a) The DFT of the monolayer WSe2 Bragg peak data (main-text Fig. 2(g)): the trend is monotonic decay with higher frequency, as predicted by a purely Debye-Waller (DW) thermal response. (b) The DFT of the 2° WSe2/MoSe2 satellite peak data (main-text Fig. 2(a)): the trend contains two peaks, the DW contribution appearing at zero frequency and a second contribution that we attribute to the twisting-motion appearing in the bin 540 ± 90 GHz, overlapping with the central frequency of the best-fit dynamical model 510 ± 90 GHz. (c) The DFT of the 57° WSe2/MoSe2 satellite peak data (main-text Fig. 2(d)): the DW contribution is peaked at 160 ± 80 GHz, which is a windowing artifact indicating that the average change in diffraction intensity over all points in the time-scan is zero, i.e., the positive change mostly cancels the negative change. A second peak is present in the bin 830 ± 80 GHz, whereas the dynamical model of the experiment best fits 510 ± 90 GHz (the model spectrum is shown in main-text Fig. 2(f)): further discussion can be found in the Supplementary Information.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Voigt profile fits to 2° WSe2/ MoSe2 UED data.

Profiles are taken from lineouts labelled in Extended Data Fig. 1(a), and indicate an alternative way to estimate the diffraction intensity compared to the method employed in the main text (summing counts within a region of interest). The choice of estimation technique does not change the main findings we report. (a) Example Voigt profile fit to satellite diffraction features. (b) Time series of Voigt-profile peaks fit to satellite diffraction features. Lines connecting data points are only a guide for the eye. (c) Example Voigt profile fit to atomic-scale Bragg diffraction features. (d) Time series of Voigt-profile peaks fit to atomic-scale Bragg diffraction features. Lines connecting data points are only a guide for the eye. (e)-(f) Time series of Voigt profile full-widths-at-half-maximum.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Voigt profile fits to 57° WSe2/ MoSe2 UED data.

Profiles are taken from lineouts labelled in Extended Data Fig. 1(b), and indicate an alternative way to estimate the diffraction intensity compared to the method employed in the main text (summing counts within a region of interest). The choice of estimation technique does not change the main findings we report. (a) Example Voigt profile fit to satellite diffraction features. (b) Time series of Voigt-profile peaks fit to satellite diffraction features. Lines connecting data points are only a guide for the eye. (c) Example Voigt profile fit to atomic-scale Bragg diffraction features. (d) Time series of Voigt-profile peaks fit to atomic-scale Bragg diffraction features. Lines connecting data points are only a guide for the eye. (e)-(f) Time series of Voigt profile full-widths-at-half-maximum.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Diffraction sensitivity to lattice normal modes.

(a)–(e) Sensitivity of satellite peaks to lattice normal modes for 2° WSe2 /MoSe2. In this context, we define the scattering enhancement F to be the derivative of the peak intensity I with respect to the r.m.s. atomic displacement x of the mode, normalized by the intensity I0 at zero displacement: F ≔ (dI/dx)/I0. The top-five most efficient modes are ranked from most efficient (a) to least efficient (e). (f)–(j) Sensitivity of satellite peaks to lattice normal modes for 57° WSe2/MoSe2. The top-five most efficient modes are ranked from most efficient (f) to least efficient (j).

Extended Data Fig. 7 Time- and angle-resolved photoemission spectra (trARPES).

Measurements performed on a 3° MoSe2/WSe2 heterostructure. (a) Static ARPES band structure. The dotted lines are theoretical prediction reproduced from43. The box highlights the region around the K point at which the electrons and holes are monitored. (b) Electron energy distribution curve (EDC) near valence band (VB) and the conduction band (CB) edges at K point, before and after the pump excitation. (c)(d) Time-dependent CB and VB ARPES signals showing the evolution of electron and hole populations at the K point. Solid blue lines correspond to fit to exponential decay convoluted with the time resolution of ~ 120 fs. The CB electron dynamics is best fit to a single exponential decay with time constant of 630 fs. The population of the VB holes is best fit to a double exponential decay with time constants of 2 ps and 97 ps. The TR-ARPES is performed with a 2.34 eV pump with a power density of ~ 1.2 mJ/cm2, and 21.7 eV EUV probe beam, under room temperature.

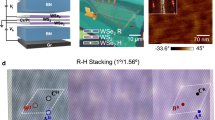

Extended Data Fig. 8 Twisting of the 57° WSe2/MoSe2 lattice versus time.

Plots are extracted from our dynamical model, fit to UED experimental data. (a) At equilibrium, atoms are displaced from from sites of the unphysical, rigidly rotated lattice by vdW forces. (b) Snapshot of the transverse displacement of atoms from equilibrium at 809 fs after photoexcitation. (c) Snapshot at 12 ps following photoexcitation, i.e., after the decay of the oscillatory transient. (d) Fitted atomic displacement as a function of radial distance from the vortex center, expressed as a twist angle.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Local twist angle estimation procedure.

Procedure for extracting the local change in twist angle from dynamic simulations of atomic motion. (a) Definition of radial distance r and tangential displacement u: local twist is defined to be du/dr in the limit r → 0. (b) Snapshot of the change in tangential displacement versus radial distance 0.9 ps after pumping the 2° WSe2/MoSe2 sample, coinciding in time with the first peak of the oscillation. Dots show atomic positions, the solid line the best fifth order polynomial fit used to compute the derivate at r = 0. Note that the tangential component of the displacement field is not single valued as a function of distance from the vortex center because the displacement field has only three-fold discrete rotational symmetry, rather than continuous rotational symmetry. The variance increases the greater the radial distance and there is consequently no improvement to the goodness of fit at polynomial orders higher than fifth. (c) A second snapshot 1.8 ps following pump arrival, coinciding with the first trough in the oscillation.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Simulated electron bands in WSe2/MoSe2.

Density-functional-theory calculations are performed according to the method summarized in the Supplementary Information. (a) 0° twist angle, color map indicates whether the electron wavefunction is mostly localized to the WSe2 layer (red) or MoSe2 layer (blue). (b) 2. 1° twist angle showing electron bands over the moiré mini-Brillouin zone, blue bands are mostly localized to the MoSe2 layer, red bands the WSe2 layer. (c) 57° twist angle, colors have the same meaning as in (b). (d) Change in bandgap ΔEg as a function of change in interlayer spacing ΔL for momentum direct (K → K) and momentum indirect (K → Γ, Q → K) transitions. The slope of the blue linear fit to Q → K is 1.1 eV/nm, the value used to estimate the deformation-potential pressure in the main text.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

This file contains six sections, Supplementary Figs. 1–5, Tables 1 and 2, and references. The Supplementary Information contains five figures: Supplementary Fig. 1 Schematic of twisted WSe2/MoSe2 in reciprocal space. a, For general twist angle, all possible first-order moiré satellites are shown. Contributions from WSe2 are shown in red, and those from MoSe2 are shown in blue. Arrows indicate the atomic-scale basis vectors q0 and q1. The region of interest at (2, −1) is highlighted, in which the UED data presented in the main text are collected. b, Definitions of the moiré scale reciprocal lattice vectors. c, Schematic of twisted WSe2/MoSe2, showing only those satellites with significant intensity when the system is in equilibrium due to strain waves caused by atomic relaxation. d,e, Torsional PLDs have a significant effect on the highlighted peaks, related to the (2, −1) region of interest by rotation. f,g, Radial PLDs have a significant effect on the highlighted peaks, related to the (2, −1) experimental region of interest by rotation. h, The highlighted peaks in the (2, −1) experimental region of interest are sensitive to torsional PLDs. i, The highlighted peaks in the (2, −1) experimental region of interest are sensitive to radial PLDs. j, The highlighted peaks in the (2, −1) region are summed in computing the satellite peak intensities shown in Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5. Supplementary Fig. 2 Illustration of phase interference. Interference due to prefactors in Supplementary equations (29)–(34). a, Chalcogenide (yellow) and metal (red) imperfectly destructively interfere at diffraction order (0, 1). b, Chalcogenide and metal atoms perfectly constructively interfere at (2, −1). c, Chalcogenide and metal atoms imperfectly constructively interfere at (0, 2). Supplementary Fig. 3 Graphical derivation of moiré superlattice vectors. See supplementary equations (41)–(43). In the small-angle approximation, a rotation is a motion orthogonal to the vector joining the displaced atom to the axis of rotation. The moiré supercell can be defined by the repetition of metal-on-metal stacking (\({{\rm{R}}}_{M}^{M}\)). A metal-on-metal stacking repeats at a distance such that the rotation has displaced an atom by one atomic lattice vector (the shortest path between adjacent atoms). Hence, the vector joining adjacent \({{\rm{R}}}_{M}^{M}\) sites is orthogonal to an atomic lattice vector, and the moiré superlattice is rotated 90° relative to the atomic lattice. Supplementary Fig. 4 Fields spanning all possible threefold symmetric moiré PLD in 2° twisted WSe2/MoSe2. a,d,g,j, In-plane visualization of the displacement fields. b,e,h,k, Changes in diffraction intensity with PLD amplitude, added to the static PLD. The WSe2 Bragg peak in the region of interest (ROI) is highlighted in red in Supplementary Fig. 1a. The MoSe2 Bragg peak is highlighted in blue, and the sum of satellite features is highlighted in black in Supplementary Fig. 1j. The WSe2 layer moves antiparallel to MoSe2. c,f,i,l, Repeating the same calculations except the WSe2 layer moves parallel to MoSe2. Supplementary Fig. 5 Fields spanning all possible threefold symmetric moiré PLD in 57° twisted WSe2/MoSe2. a,d,g,j, In-plane visualization of the displacement fields. b,e,h,k, Changes in diffraction intensity with PLD amplitude, added to the static PLD. The WSe2 Bragg peak in the region of interest (ROI) is highlighted in red in Supplementary Fig. 1a. The MoSe2 Bragg peak is highlighted in blue, and the sum of satellite features is highlighted in black in Supplementary Fig. 1j. The WSe2 layer moves antiparallel to MoSe2. c,f,i,l, Repeating the same calculations except the WSe2 layer moves parallel to MoSe2. The Supplementary Information contains two tables. Supplementary Table 1 Ab initio numerically calculated electron–phonon coupling for 0° WSe2/ MoSe2. The first column labels the phonon mode, the second column shows coupling to the conduction band at the K point, and the final column shows coupling to the valence band at the K point. Optical intralayer modes \({{A}^{^{\prime} }}_{1},{E}^{^{\prime} }\) carry subscripts indicating the layer affected. Supplementary Table 2 Reproduction of main-text Table 1.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Duncan, C.J.R., Johnson, A.C., Maity, I. et al. Photoinduced twist and untwist of moiré superlattices. Nature 647, 619–624 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09707-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09707-3