Abstract

Most baryons in present-day galaxy clusters exist as hot gas (≳107 K), forming the intracluster medium (ICM)1. Cosmological simulations predict that the mass and temperature of the ICM decline towards earlier times, as intracluster gas in younger clusters is still assembling and being heated2,3,4. To date, hot ICM has been securely detected only in a few systems at or above z ≈ 2, leaving the timing and mechanism of ICM assembly uncertain5,6,7. Here we report the direct observation of hot intracluster gas via its thermal Sunyaev–Zeldovich signature in the protocluster SPT2349–56 with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array. SPT2349–56 hosts a large molecular gas reservoir and three radio-loud active galactic nuclei (AGN) within an approximately 100-kpc region at z = 4.3 (refs. 8,9,10,11). The measurement implies a thermal energy of about 1061 erg in the core, about 10 times more than gravity alone should produce. Contrary to current theoretical expectations3,4,12, the hot ICM in SPT2349–56 demonstrates that substantial heating can occur very early in cluster assembly, depositing enough energy to overheat the nascent ICM well before mature clusters become common at z ≈ 2.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The ALMA (2015.1.01543.T, 2017.1.00273.S, 2022.1.00495.S and 2023.1.00124.S), JWST (JWST-GO-06669), and HST (HST-GO-15701) data used in this work are publicly available on the ALMA science archive (https://almascience.nrao.edu/aq/) and MAST service (https://mast.stsci.edu).

References

Bryan, G. L. & Norman, M. L. Statistical properties of X-ray clusters: analytic and numerical comparisons. Astrophys. J. 495, 80–99 (1998).

Chiang, Y.-K., Makiya, R., Ménard, B. & Komatsu, E. The cosmic thermal history probed by Sunyaev–Zeldovich effect tomography. Astrophys. J. 902, 56 (2020).

Li, Q. et al. THE THREE HUNDRED Project: the evolution of physical baryon profiles. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 523, 1228–1246 (2023).

Rohr, E. et al. The cooler past of the intracluster medium in TNG-cluster. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 536, 1226–1250 (2025).

Mantz, A. B. et al. The XXL Survey. XVII. X-ray and Sunyaev–Zel’dovich properties of the redshift 2.0 galaxy cluster XLSSC 122. Astron. Astrophys. 620, 2 (2018).

Gobat, R. et al. Sunyaev-Zel’dovich detection of the galaxy cluster Cl J1449+0856 at z = 1.99: the pressure profile in uv space. Astron. Astrophys. 629, 104 (2019).

Di Mascolo, L. et al. Forming intracluster gas in a galaxy protocluster at a redshift of 2.16. Nature 615, 809–812 (2023).

Miller, T. B. et al. A massive core for a cluster of galaxies at a redshift of 4.3. Nature 556, 469–472 (2018).

Chapman, S. C. et al. Brightest cluster galaxy formation in the z = 4.3 protocluster SPT 2349-56: discovery of a radio-loud active galactic nucleus. Astrophys. J. 961, 120 (2024).

Zhou, D. et al. A large molecular gas reservoir in the protocluster SPT2349-56 at z = 4.3. Astrophys. J. Lett. 982, 17 (2025).

Chapman, S. C. et al. An overabundance of radio-AGN in the SPT2349-56 protocluster: preheating the intra-cluster medium. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2511.17814 (2025).

Sunyaev, R. A. & Zeldovich, Y. B. Formation of clusters of galaxies; protocluster fragmentation and intergalactic gas heating. Astron. Astrophys. 20, 189 (1972).

Sunyaev, R. A. & Zeldovich, I. B. Microwave background radiation as a probe of the contemporary structure and history of the universe. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 18, 537–560 (1980).

Voit, G. M. Tracing cosmic evolution with clusters of galaxies. Rev. Mod. Phys. 77, 207–258 (2005).

Wang, G. C. P. et al. Overdensities of submillimetre-bright sources around candidate protocluster cores selected from the South Pole Telescope survey. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 508, 3754–3770 (2021).

Hill, R. et al. Megaparsec-scale structure around the protocluster core SPT2349-56 at z = 4.3. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 495, 3124–3159 (2020).

McCarthy, I. G., Babul, A., Bower, R. G. & Balogh, M. L. Towards a holistic view of the heating and cooling of the intracluster medium. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 386, 1309–1331 (2008).

Henden, N. A., Puchwein, E. & Sijacki, D. The redshift evolution of X-ray and Sunyaev-Zel’dovich scaling relations in the FABLE simulations. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 489, 2439–2470 (2019).

Bennett, J. S., Sijacki, D., Costa, T., Laporte, N. & Witten, C. The growth of the gargantuan black holes powering high-redshift quasars and their impact on the formation of early galaxies and protoclusters. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 527, 1033–1054 (2024).

Carlstrom, J. E., Holder, G. P. & Reese, E. D. Cosmology with the Sunyaev-Zel’dovich effect. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 40, 643–680 (2002).

Mroczkowski, T. et al. Astrophysics with the spatially and spectrally resolved Sunyaev-Zeldovich effects. A millimetre/submillimetre probe of the warm and hot universe. Space Sci. Rev. 215, 17 (2019).

Spacek, A., Scannapieco, E., Cohen, S., Joshi, B. & Mauskopf, P. Constraining AGN feedback in massive ellipticals with South Pole telescope measurements of the thermal Sunyaev-Zel’dovich effect. Astrophys. J. 819, 128 (2016).

Arnaud, M. et al. The universal galaxy cluster pressure profile from a representative sample of nearby systems (REXCESS) and the YSZ–M500 relation. Astron. Astrophys. 517, 92 (2010).

Maughan, B. J., Giles, P. A., Randall, S. W., Jones, C. & Forman, W. R. Self-similar scaling and evolution in the galaxy cluster X-ray luminosity-temperature relation. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 421, 1583–1602 (2012).

Planck Collaboration. Planck 2013 results. XX. Cosmology from Sunyaev-Zeldovich cluster counts. Astron. Astrophys. 571, 20 (2014).

McDonald, M. et al. The remarkable similarity of massive galaxy clusters from z ~ 0 to z ~ 1.9. Astrophys. J. 843, 28 (2017).

Mostoghiu, R. et al. The Three Hundred Project: the evolution of galaxy cluster density profiles. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 483, 3390–3403 (2019).

Marrone, D. P. et al. LoCuSS: the Sunyaev-Zel’dovich effect and weak-lensing mass scaling relation. Astrophys. J. 754, 119 (2012).

Bocquet, S. et al. Cluster cosmology constraints from the 2500 deg2 SPT-SZ survey: inclusion of weak gravitational lensing data from Magellan and the Hubble Space Telescope. Astrophys. J. 878, 55 (2019).

Bigwood, L., Bourne, M. A., Iršič, V., Amon, A. & Sijacki, D. The case for large-scale AGN feedback in galaxy formation simulations: insights from XFABLE. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 542, 3206–3230 (2025).

Lucie-Smith, L. et al. Cosmological feedback from a halo assembly perspective. Phys. Rev. D. 112, 063541 (2025).

Nagarajan, A. et al. Weak-lensing mass calibration of the Sunyaev-Zel’dovich effect using APEX-SZ galaxy clusters. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 488, 1728–1759 (2019).

Andreon, S. et al. Witnessing the intracluster medium assembly at the cosmic noon in JKCS 041. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 522, 4301–4309 (2023).

van Marrewijk, J. et al. XLSSC 122 caught in the act of growing up: spatially resolved SZ observations of a z = 1.98 galaxy cluster. Astron. Astrophys. 689, 41 (2024).

Remus, R.-S., Dolag, K. & Dannerbauer, H. The young and the wild: what happens to protoclusters forming at redshift z ≈ 4? Astrophys. J. 950, 191 (2023).

Aljamal, E. et al. Mass proxy quality of massive halo properties in the IllustrisTNG and FLAMINGO simulations: I. Hot gas. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 544, 67–94 (2025).

Bassini, L. et al. The DIANOGA simulations of galaxy clusters: characterising star formation in protoclusters. Astron. Astrophys. 642, 37 (2020).

Lim, S. et al. Is there enough star formation in simulated protoclusters? Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 501, 1803–1822 (2021).

Hlavacek-Larrondo, J. et al. X-ray cavities in a sample of 83 SPT-selected clusters of galaxies: tracing the evolution of AGN feedback in clusters of galaxies out to z = 1.2. Astrophys. J. 805, 35 (2015).

Valentino, F. et al. A giant Lyα nebula in the core of an X-ray cluster at z = 1.99: implications for early energy injection. Astrophys. J. 829, 53 (2016).

Cielo, S., Babul, A., Antonuccio-Delogu, V., Silk, J. & Volonteri, M. Feedback from reorienting AGN jets. I. Jet-ICM coupling, cavity properties and global energetics. Astron. Astrophys. 617, 58 (2018).

Heckman, T. M. & Best, P. N. A global inventory of feedback. Galaxies 11, 21 (2023).

Heckman, T. M., Roy, N., Best, P. N. & Kondapally, R. Mergers, radio jets, and quenching star formation in massive galaxies: quantifying their synchronized cosmic evolution and assessing the energetics. Astrophys. J. 977, 125 (2024).

Rennehan, D., Babul, A., Moa, B. & Davé, R. The OBSIDIAN model: three regimes of black hole feedback. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 532, 4793–4809 (2024).

Huško, F. et al. A hybrid active galactic nucleus feedback model with spinning black holes, winds and jets. Preprint at arxiv.org/abs/2509.05179 (2025)

Begelman, M. C. & Cioffi, D. F. Overpressured cocoons in extragalactic radio sources. Astrophys. J. Lett. 345, 21 (1989).

Nesvadba, N. P. H., Lehnert, M. D., De Breuck, C., Gilbert, A. M. & van Breugel, W. Evidence for powerful AGN winds at high redshift: dynamics of galactic outflows in radio galaxies during the “Quasar Era”. Astron. Astrophys. 491, 407–424 (2008).

Fabian, A. C. Observational evidence of active galactic nuclei feedback. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 50, 455–489 (2012).

Chadayammuri, U., Tremmel, M., Nagai, D., Babul, A. & Quinn, T. Fountains and storms: the effects of AGN feedback and mergers on the evolution of the intracluster medium in the ROMULUSC simulation. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 504, 3922–3937 (2021).

Grayson, S., Scannapieco, E. & Davé, R. Distinguishing active galactic nuclei feedback models with the thermal Sunyaev–Zel’dovich effect. Astrophys. J. 957, 17 (2023).

Altamura, E. et al. EAGLE-like simulation models do not solve the entropy core problem in groups and clusters of galaxies. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 520, 3164–3186 (2023).

Gardner, A., Baxter, E., Raghunathan, S., Cui, W. & Ceverino, D. Prospects for studying the mass and gas in protoclusters with future CMB observations. Open J. Astrophys. 7, 2 (2024).

Vogelsberger, M. et al. The uniformity and time-invariance of the intra-cluster metal distribution in galaxy clusters from the IllustrisTNG simulations. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 474, 2073–2093 (2018).

Huško, F., Lacey, C. G., Schaye, J., Nobels, F. S. J. & Schaller, M. Winds versus jets: a comparison between black hole feedback modes in simulations of idealized galaxy groups and clusters. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 527, 5988–6020 (2024).

Mantz, A. B. et al. The XXL Survey. V. Detection of the Sunyaev-Zel’dovich effect of the redshift 1.9 galaxy cluster XLSSU J021744.1-034536 with CARMA. Astrophys. J. 794, 157 (2014).

Planck Collaboration. Planck 2015 results. XIII. Cosmological parameters. Astron. Astrophys. 594, 13 (2016).

Bushouse, H. et al. JWST calibration pipeline. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6984365 (2025).

Bradley, L. et al. Astropy/photutils: 2.0.2. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13989456 (2024).

Fujimoto, S. et al. ALMA census of faint 1.2 mm sources down to ~0.02 mJy: extragalactic background light and dust-poor, high-z galaxies. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 222, 1 (2016).

Fujimoto, S. et al. ALMA Lensing Cluster Survey: deep 1.2 mm number counts and infrared luminosity functions at z = 1–8. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 275, 36 (2024).

Tazzari, M. Mtazzari/uvplot (v0.1.1). Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1003113 (2017).

Wang, T. et al. Discovery of a galaxy cluster with a violently starbursting core at z = 2.506. Astrophys. J. 828, 56 (2016).

Grishin, K. A. et al. Spectroscopic confirmation of the galaxy clusters CARLA J0950+2743 at z = 2.363 and CARLA-Ser J0950+2743 at z = 2.243. Astron. Astrophys. 693, 1 (2025).

Travascio, A. et al. X-ray view of a massive node of the cosmic web at z = 3 II. Discovery of extended X-ray emission around a hyperluminous QSO. Preprint at arxiv.org/abs/2508.20074 (2025).

Diemer, B. COLOSSUS: a Python toolkit for cosmology, large-scale structure, and dark matter halos. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 239, 35 (2018).

Diemer, B. & Joyce, M. An accurate physical model for halo concentrations. Astrophys. J. 871, 168 (2019).

Hill, R. et al. Rapid build-up of the stellar content in the protocluster core SPT2349-56 at z = 4.3. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 512, 4352–4377 (2022).

Vito, F. et al. Fast supermassive black hole growth in the SPT2349–56 protocluster at z = 4.3. Astron. Astrophys. 689, A130 (2024).

Heckman, T. M. & Best, P. N. The coevolution of galaxies and supermassive black holes: insights from surveys of the contemporary Universe. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 52, 589–660 (2014).

Nusser, A., Silk, J. & Babul, A. Suppressing cluster cooling flows by self-regulated heating from a spatially distributed population of active galactic nuclei. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 373, 739–746 (2006).

Jennings, F. J., Babul, A., Davé, R., Cui, W. & Rennehan, D. HYENAS: X-ray bubbles and cavities in the intragroup medium. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 536, 145–165 (2025).

Kondapally, R. et al. Cosmic evolution of radio-AGN feedback: confronting models with data. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 523, 5292–5305 (2023).

Venkateshwaran, A. et al. Kinematic analysis of z = 4.3 galaxies in the SPT2349–56 protocluster core. Astrophys. J. 977, 161 (2024).

Spilker, J. S. et al. Ubiquitous molecular outflows in z > 4 massive, dusty galaxies. II. Momentum-driven winds powered by star formation in the early Universe. Astrophys. J. 905, 86 (2020).

Duan, X. & Guo, F. On the energy coupling efficiency of AGN outbursts in galaxy clusters. Astrophys. J. 896, 114 (2020).

O’Dea, C. P. The compact steep-spectrum and gigahertz peaked-spectrum radio sources. Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac. 110, 493–532 (1998).

Yamada, M., Sugiyama, N. & Silk, J. The Sunyaev-Zeldovich effect by cocoons of radio galaxies. Astrophys. J. 522, 66–73 (1999).

Bromberg, O., Nakar, E., Piran, T. & Sari, R. The propagation of relativistic jets in external media. Astrophys. J. 740, 100 (2011).

Cen, R. Global preventive feedback of powerful radio jets on galaxy formation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 121, 2402435121 (2024).

Boselli, A., Fossati, M. & Sun, M. Ram pressure stripping in high-density environments. Astron. Astrophys. Rev. 30, 3 (2022).

Astropy Collaboration. The Astropy Project: sustaining and growing a community-oriented open-source project and the latest major release (v5.0) of the core package. Astrophys. J. 935, 167 (2022).

Ginsburg, A. et al. astroquery: an astronomical web-querying package in Python. Astron. J. 157, 98 (2019).

CASA Team. CASA, the common astronomy software applications for radio astronomy. Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac. 134, 114501 (2022).

Hunter, J. D. Matplotlib: a 2D graphics environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 9, 90–95 (2007).

Harris, C. R. et al. Array programming with NumPy. Nature 585, 357–362 (2020).

The pandas development team. pandas-dev/pandas: Pandas. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3509134 (2025).

Ginsburg, A. et al. radio-astro-tools/spectral-cube: v.0.4.4. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.2573901 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank L. Sage for his guidance and feedback, which greatly improved the clarity and presentation of the paper. We thank S. Andreon, A. Babul, L. Bleem, G. Holder, A. Mantz, D. Marrone, D. Nagai, A. Richards, D. Rennehan, J. Sayers, D. Wang, B. Yue and N. Zhang for their discussions on this work. We thank the anonymous referees for their comments and suggestions, which improved the clarity of this work. This paper makes use of the following ALMA data: ADS/JAO.ALMA#2015.1.01543.T, ADS/JAO.ALMA#2017.1.00273.S, ADS/JAO.ALMA#2022.1.00495.S and ADS/JAO.ALMA#2023.1.00124.S. ALMA is a partnership of ESO (representing its member states), NSF (USA) and NINS (Japan), together with NRC (Canada), NSTC and ASIAA (Taiwan) and KASI (Republic of Korea), in cooperation with the Republic of Chile. The Joint ALMA Observatory is operated by ESO, AUI/NRAO and NAOJ. The National Radio Astronomy Observatory is a facility of the National Science Foundation operated under cooperative agreement by Associated Universities. This research used the Canadian Advanced Network for Astronomy Research (CANFAR) operated in partnership by the Canadian Astronomy Data Centre and The Digital Research Alliance of Canada, with support from the National Research Council of Canada, the Canadian Space Agency, CANARIE and the Canadian Foundation for Innovation. This research is based on observations made with the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope obtained from the Space Telescope Science Institute, which is operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, under NASA contract no. NAS 5-26555. These observations are associated with program #15701. This work is based (in part) on observations made with the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope. The data were obtained from the Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes at the Space Telescope Science Institute, which is operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, under NASA contract no. NAS 5-03127 for JWST. These observations are associated with program #06669. This research was supported in part by grant NSF PHY-2309135 to the Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics (KITP). The SPT is supported by the NSF through grant no. OPP-1852617. This work was partially supported by the Center for AstroPhysical Surveys (CAPS) at the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA), University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. D.Z., S.C.C., R.H. and G.C.P.W. acknowledge support from NSERC-6740. M. Aravena is supported by FONDECYT grant no. 1252054 and acknowledges support from the ANID Basal Project FB210003 and ANID MILENIO NCN2024_112. M.S. was financially supported by Becas-ANID scholarship #21221511 and also acknowledges support from ANID BASAL project FB210003.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.Z. reduced and analysed the data, interpreted the results, produced the figures and drafted the paper. S.C.C. conceived, designed and supervised the projects. R.G. produced the tSZ model of SPT2349–56 for the ALMA proposal. R.D. and R.G. validated the fidelity of the tSZ decrement. P.A.-A. calculated the redshift-evolution of the Compton-Y parameter and hot-gas fraction from TNG-Cluster simulations. S.K. reduced the JWST NIRCam data. D.Z., S.C.C., M. Aravena, P.A.-A., M. Archipley, J.C., R.D., L.D.M., R.G., T.R.G., R.H., S.K., K.A.P., V.R.P., A.C.P., C.R., M.S., J.S.S., N.S., V.J.D., J.D.V., D.V., G.C.P.W. and A.W. contributed substantially to discussing the results and preparing the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 RGB image of the protocluster core.

The zoomed-in version of Fig. 1. The positions of submillimeter-luminous protocluster galaxies are indicated by their alphabetical names based on their rank-ordered 850 μm flux densities in Ref. 8. Three radio-loud AGN (A, C, and E) are highlighted with their names in red. Due to the crowdedness of the protocluster core, labels of faint members with a negligible 3 mm flux density are hidden in this figure for clarity.

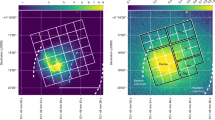

Extended Data Fig. 2 ALMA high-resolution continuum map with the tSZ contours.

The solid contours are tSZ signal from −2σ to −8σ with steps of −1σ. The dashed contours indicate regions with values above 2σ. The number labels on sources are IDs from the continuum source catalog in Extended Data Table 1. The primary beam responses are indicated as dotted lines. The synthesized beams of the continuum image (‘ALMA high-res’) and the SZ decrement (‘SZ’) are indicated in the upper-left and the bottom-left corners, respectively.

Extended Data Fig. 3 ALMA low-resolution tSZ map.

The solid contours are tSZ signal from −2σ to −8σ with steps of −1σ. The dashed contours indicate regions with pixel values above 2σ. The primary beam responses are indicated as dotted lines. The synthesized beam of the SZ decrement is indicated in the bottom-left corner.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Curve-of-growth analysis for the tSZ decrement.

The flux density of the tSZ decrement and the flux-scaled synthesized beam of the ‘SZ’ map are indicated as the red solid and the blue dashed line, respectively. The overdensity radii are also shown as black dotted lines. The turnover in the decrement at radii ≳ 25″ may indicate dirty-beam sidelobes from an imperfect CLEANing process.

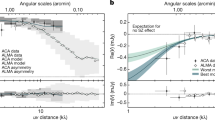

Extended Data Fig. 5 uv profile of the original and continuum subtracted data.

The real part of the averaged amplitude measured from the continuum-subtracted measurement sets as a function of uv-distance with uv bins of 3kλ. The errorbars are derived from visibility weightings. The negative signal becomes stronger at a shorter uv distance, suggesting that the tSZ decrement can be limited by the uv-coverage of the ACA and ALMA observations.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Compton-y map with dust continuum contours.

The solid contours are 3 mm continuum emission drawn at [2.5σ, 5σ, 10σ, 20σ, 40σ, 80σ] from the ‘ALMA high-res’ map. The primary beam responses are indicated at dotted lines. The synthesized beams of 3 mm continuum and Compton-y map are indicated in the upper-left and the bottom-left corners.

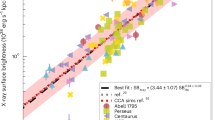

Extended Data Fig. 8 Halo mass as a function of ICM temperature.

The coloured curves show combinations of halo mass M200 and mass-weighted ICM temperature ⟨T200⟩ that reproduce the observed tSZ decrement for different assumed ICM fractions (from 0.02 to 0.10, as labelled). The corresponding ICM mass MICM is indicated in the top axis. The sub-virialized (blue) and super-virialized (red) regions are separated by the virialized temperature for different M200. The dotted line indicates the dynamical mass of SPT2349−5616. The light hatched band denotes the possible MICM range allowed by the universal baryonic fraction fb = 0.155. Without assuming an extreme ICM fraction fICM, either a more massive virialized halo or a super-virialized ICM gas is necessary to match the observed tSZ decrement.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Cosmic evolution of the hot gas (>107 K) fraction in galaxy clusters.

The fraction of hot ICM (Mhot ICM,500/M500) within r500 as a function of redshift obtained from the TNG-Cluster simulation. Based on the total mass M200 at z = 0, the clusters are placed in three mass bins, high mass (M200 > 1015 M⊙, black solid line), intermediate mass (5 × 1014 M⊙ < M200 < 1015 M⊙, red dashed line), and low mass (M200 < 5 × 1014 M⊙, orange dash-dotted line). The corresponding shaded regions represent the values between the 16th and 84th percentiles in individual mass bins.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

This file contains Supplementary Methods, Figs. 1–5, Tables 1–3, and references.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, D., Chapman, S.C., Aravena, M. et al. Sunyaev–Zeldovich detection of hot intracluster gas at redshift 4.3. Nature 649, 1130–1133 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09901-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09901-3