Abstract

The medial temporal lobe, and particularly the hippocampus, has been proposed to encode items in context1,2. Although hippocampal memory representations are largely context-dependent in rodents3,4, concept cells in humans appear to be context-invariant5. However, it remains unknown how item and context information are combined to form or retrieve integrated item-in-context memories at the single-neuron level in humans. Here we show that coordinated activity of distinct neuronal populations supports item-in-context memory. In a context-dependent picture-comparison task, we recorded 3,109 neurons from 16 neurosurgical patients, identifying 597 stimulus-modulated (pre-screened) and 200 context-modulated neurons (2.95% in the amygdala, 7.68% in the parahippocampal cortex, 5.68% in the entorhinal cortex and 9.42% in the hippocampus). Their co-firing combined different comparison questions (contexts) with two subsequent pictures (stimuli) through neuronal reinstatement of question contexts. Both populations were largely separate, generalized across the preferred dimension of each other, and covaried with behavioural performance. Following experimental pairing of stimuli and context, firing of entorhinal stimulus neurons predicted that of hippocampal context neurons after tens of milliseconds. Overall, synaptic modifications and co-firing of stimulus and context neurons could contribute to item-in-context memory, specify which stimulus memories need to be retrieved, and even generalize memories through mutual reinstatement of largely separate, orthogonal representations. By contrast, only 50 stimulus–context neurons represented specific picture–question combinations, consistent with limited pattern separation in the human medial temporal lobe, favouring flexible generalization over rigid conjunctive coding.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The medial temporal lobe (MTL), and particularly the hippocampus, is essential for declarative memories of items in context1,2. In humans, the hippocampus has also been implicated in generalization6,7. With ease, we recall multiple memories involving a particular memory item, for example, different dinners with our friend. A uniquely human single-neuron correlate of memory items is represented by concept neurons in the MTL, which selectively and invariantly respond to stimuli containing a preferred semantic concept8 (for example, our friend). Concept neurons are apparently not modulated by the context of an item, and thus seem suited for generalization5 (but see ref. 9). As humans can also recall items based on context, concept neurons may be complemented by neurons representing context. However, remembering contexts such as time, task or location together with memory items requires the combination of item and context information10. For example, we remember when we had dinner with our friend, whether it was work related or where it took place. Furthermore, we can recall a specific restaurant visit based on item and context information. Initial evidence has suggested that separate neurons in the MTL represent contexts11,12,13. However, it remains unclear how neural correlates of item and context memory are combined to form or retrieve integrated item-in-context memories at the single-neuron level in humans. Recording from 16 patients undergoing surgery to treat epilepsy, we investigated how human MTL neurons combine item and context representations. We devised a task in which pairs of pictures were presented sequentially following different contexts, namely, questions (for example, ‘Bigger?’) that specified how to compare the two pictures. This required participants to remember items (that is, two pictures) in a specific context. Here ‘context’ refers to interactive or task context rather than independent or background context14. Only a small fraction of neurons encoded individual item–context combinations as reported in rodents. Instead, separate populations of neurons represented either items or contexts in an orthogonal encoding scheme, reflecting the ability of humans to generalize memories along each dimension separately. Finally, we show how item and context information is combined via co-activation, synaptic modification or reinstatement, contributing to item-in-context memory and the retrieval of contextually relevant item memories.

Distinct neurons for content and context

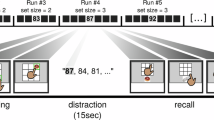

During 49 experimental sessions, we recorded from 3,109 neurons in the amygdala, parahippocampal cortex, entorhinal cortex and hippocampus of 16 neurosurgical patients implanted with depth electrodes for invasive seizure monitoring. Pairs of pictures were presented on a laptop screen in different contexts, namely, five questions (‘Bigger?’, ‘Last seen in real life?’, ‘Older?’ or ‘More expensive?’, ‘Like better?’ and ‘Brighter?’) that specified how the pictures should be compared (Fig. 1a). For each session, four pictures eliciting selective neuronal responses in a previous screening were selected. Each trial began with a context-providing question (such as Bigger?), followed by a sequence of two of the four pictures (stimuli) that needed to be remembered in context and compared accordingly. Patients then chose the picture that best answered the question (for example, which depicted something bigger) and indicated whether it was shown first or second via the keyboard. Most answers were highly consistent and transitive, with performance greatly exceeding chance in all but one excluded session and not differing across questions (P = 0.083; Kruskal–Wallis test; Extended Data Fig. 1). Furthermore, answers strongly correlated with ground truths for Bigger? and More expensive? or Older? (mean ρ = 0.760, P = 6.47 × 10−10; Extended Data Fig. 2). To quantify the representation of stimulus and context during picture presentations, repeated-measures two-way 4 × 5 analysis of variance (ANOVA) with factors picture, question and their interaction were computed for each neuron (α = 0.001; effect sizes in Fig. 2e).

Although most stimulus neurons only encode picture identity, context is either represented alone, in conjunction with stimulus identity or as modulation of stimulus-specific firing rates. a, Paradigm with exemplary trial of the stimulus-comparison task (here for the context question Bigger?). During 300 trials, participants had to compare pictures according to a context question. Each trial contained one of five questions (Bigger?, Last seen (in real life)?, More expensive? or Older?, Like better? and Brighter?), a sequence of two pictures (out of four) and an answer prompt displaying ‘1 or 2?’. Participants indicated the sequential position of the picture that best answered the question by pressing keys 1 or 2. Question and answer screens were self-triggered. Event durations are printed underneath. b–e, Example neurons with spike density plots in the upper left whose firing rate (Hz) during picture presentations (0–1,000 ms) is visualized by raster plots and histograms as a function of question and stimulus identity. b, A stimulus neuron that selectively increased firing whenever a biscuit was shown, irrespective of which question context was presented. The neuron did not respond to any other picture. c, This context neuron increased firing during picture presentations whenever the trial started with the question Older? (top left) as opposed to any other question (bottom left) regardless of stimulus identity (top row). d, Example of a stimulus–context interaction neuron whose firing increased when the question was Brighter image? and the stimulus depicted a train (top left) in contrast to other combinations of question and stimulus. e, This contextual stimulus neuron only responded to its preferred picture (hamburger, top left), but more strongly in the context of the question Last seen (in real life)?.

a, Venn diagram of a significant number of neuron types defined by repeated-measures two-way ANOVA with factors stimulus (stimulus neurons in red, ochre, grey or pink), question (context neurons in green, ochre, grey or light blue) or their interaction (stimulus–context interaction neurons in grey, pink, blue or light blue) during picture presentations (α = 0.001) from 3,109 neurons. Intersections denote multiple effects. Most stimulus neurons were not modulated by context but overlapped with context neurons (contextual stimulus neurons) or stimulus–context interaction neurons. b, Probabilities of context or stimulus–context interaction neurons across brain regions (absolute numbers above the bars). The significance asterisks denote binomial tests versus chance (dotted line). Neurons in all MTL regions were strongly modulated by context and stimulus–context. A, amygdala; EC, entorhinal cortex; H, hippocampus; PHC, parahippocampal cortex. c, Analogous to panel b with probabilities of context conditioned on stimulus modulation (stimulus | no stimulus). The significance asterisks denote Fisher’s exact test results from regional contingency tables. Stimulus neurons were more likely to be modulated by context (contextual stimulus neurons) than non-stimulus neurons in all MTL regions (significant in amygdala and hippocampus), especially the hippocampus. d, Analogous to panel c, with probabilities of significant interactions (stimulus–context). Stimulus–context interaction neurons with conjunctive representations were most frequent in the hippocampus. NS, not significant. e, Boxplots of patient-averaged effect sizes from all 3,109 neurons \(({\eta }_{{\rm{partial}}}^{2})\) for factors stimulus, context and interaction (stimulus–context). Data (purple) are compared with stratified-shuffled controls (grey; Wilcoxon signed-rank test). Effect sizes markedly exceeded chance for stimulus (\({\eta }_{p}^{2}\)(real) = 0.114, \({\eta }_{p}^{2}\)(control) = 0.034, Ppatient = 1.313 × 10−3, Psession = 3.330 × 10−9); and context (\({\eta }_{{\rm{p}}}^{2}\)(real) = 0.059, \({\eta }_{{\rm{p}}}^{2}\)(control) = 0.034, Ppatient = 1.313 × 10−3 and Psession = 4.827 × 10−9). The difference for stimulus–context was smaller but significant (\({\eta }_{{\rm{p}}}^{2}\)(real) = 0.036, \({\eta }_{{\rm{p}}}^{2}\)(control) = 0.034, Ppatient = 1.840 × 10−2 and Psession = 3.140 × 10−3). The insets depict scatter plots of \({\eta }_{{\rm{p}}}^{2}\) of context (left) or stimulus–context (right) versus stimulus. The dashed lines indicate the smallest significant effect size (α = 0.001). ****P < 0.0001, **P < 0.01 and *P < 0.05 (Bonferroni corrected).

Although we expected to find many neurons with a significant main effect of stimulus due to our pre-selection of response-eliciting pictures, it was unclear how context would be encoded. Distinct neuronal populations were identified. Most neurons only exhibited a significant main effect of either stimulus (Fig. 1b) or context (Fig. 1c) and were termed (mere) stimulus and context neurons, respectively. Figure 1b shows an example of a (mere) stimulus neuron, selectively increasing firing to ‘biscuit’, irrespective of context (that is, comparison prompted by the question). Figure 1c shows a (mere) context neuron, whose firing distinguished only context during the late phase of picture presentations. Whenever the trial started with Older?, but not in any other context, this neuron responded to all pictures regardless of stimulus identity. Furthermore, we identified neurons with a significant interaction that encoded stimulus and context conjunctively (Fig. 1d). These neurons only responded when a specific picture (for example, train) was shown in a specific context (for example, Brighter image?), but not for any other picture–context combination. Finally, although mere stimulus (MS) neurons (only significant main effect of stimulus) were much more common (Fig. 1b), we also identified contextual stimulus neurons defined by significant main effects of both stimulus and context (irrespective of interaction), for example, selectively responding to the picture of a hamburger, yet particularly strongly when the context was Last seen in real life? (Fig. 1e).

Distribution of content and context

Context was represented during picture presentations in substantially more neurons than expected by chance. Out of 3,109 recorded units, 200 exhibited a main effect of question P < 0.001 in a repeated-measures two-way ANOVA with factors stimulus and question (including interaction; Fig. 2a), largely exceeding the expected number of roughly 3 units (two-sided binomial test, P < 2.225 × 10−308). This amounted to 2.95% of neurons in the amygdala (31 of 1,051), 7.68% in the parahippocampal cortex (37 of 482), 5.68% in the entorhinal cortex (25 of 440) and 9.42% in the hippocampus (107 of 1,136), all far exceeding chance (Fig. 2b; two-sided binomial tests, all P < 2.225 × 10−308). Although most neurons that encoded stimulus did not encode context (524 of 597), the fraction that did or that exhibited an interaction was still highly significant in two-sided binomial tests: out of the 597 neurons with a main effect of stimulus, 73 also showed a main effect of question with P < 0.001 (12.23%; P < 2.225 × 10−308) and 31 an interaction with P < 0.001 (5.19%; P < 2.225 × 10−308). Although the populations were largely distinct, a significant main effect of context was more prevalent among neurons with than without an additional main effect of stimulus, particularly in the amygdala (7.83% versus 1.67%), the entorhinal cortex (10.29% versus 4.84%) and the hippocampus (21.26% versus 7.28%; Fig. 2c). Mere context (MC) neurons (only significant main effect of context) were most frequent in the parahippocampal cortex (6.96%, 25 of 359) and rarest in the amygdala (1.67%, 14 of 836). Moreover, significant interactions (P < 0.001) capturing conjunctive representations strongly exceeded chance in two-sided binomial tests (1.61%, 50 of 3,109; P < 2.225 × 10−308), particularly in the amygdala (1.05%, 11 of 1,051; P = 1.588 × 10−8), the parahippocampal cortex (2.28%, 11 of 482; P = 4.733 × 10−12) and the hippocampus (2.29%, 26 of 1,136; P < 2.225 × 10−308; Fig. 2b), especially among hippocampal stimulus neurons (10.34%, 18 of 174; Fig. 2d). To account for potential statistical dependencies between factors or neurons, ANOVA effect sizes of all neurons were compared with stratified label-shuffling controls, irrespective of significance (Fig. 2e; see Methods). Confirming previous results, patient-averaged effect sizes of stimulus (\({\eta }_{{\rm{p}}}^{2}\)(real) = 0.114, \({\eta }_{{\rm{p}}}^{2}\)(control) = 0.034, Ppatient = 1.313 × 10−3 and Psession = 3.330 × 10−9), context (\({\eta }_{{\rm{p}}}^{2}\)(real) = 0.059, \({\eta }_{{\rm{p}}}^{2}\)(control) = 0.034, Ppatient = 1.313 × 10−3 and Psession = 4.827 × 10−9) and their interaction (\({\eta }_{{\rm{p}}}^{2}\)(real) = 0.036, \({\eta }_{{\rm{p}}}^{2}\)(control) = 0.034, Ppatient = 1.840 × 10−2 and Psession = 3.140 × 10−3) all significantly differed from controls (two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, Bonferroni corrected). Linear mixed-effects models with a fixed intercept (capturing grand population effect size differences) and random intercepts for patients, fitted across all recorded neurons, confirmed that real effect sizes significantly exceeded permutation-based baselines for all three ANOVA factors: stimulus (β = 0.080, 95% CI 0.065–0.095, P = 2.177 × 10−24), context (β = 0.025, 95% CI 0.019–0.032, P = 4.186 × 10−14) and stimulus–context interaction (β = 0.002, 95% CI 0.001–0.003, P = 2.269 × 10−6). Finally, we examined whether stimulus–context neurons were more prevalent in areas with higher proportions of stimulus or context neurons (Extended Data Fig. 3). Across all session–site combinations (n = 168), stimulus–context neuron proportions correlated significantly with both stimulus (Spearman’s ρ = 0.177, P = 0.022) and context neuron proportions (ρ = 0.487, P < 0.001), particularly in the hippocampus and amygdala, where stimulus–context proportions correlated with both stimulus (ρ = 0.274, P = 0.032 for the hippocampus; and ρ = 0.329, P = 0.012 for the amygdala) and context neuron proportions (ρ = 0.471, P < 0.001 for the hippocampus; and ρ = 0.487, P = 0.003 for the amygdala). By contrast, the parahippocampal and entorhinal cortices showed significant correlations exclusively with context (ρ = 0.569, P < 0.001 for the parahippocampal cortex; and ρ = 0.377, P = 0.023 for the entorhinal cortex) but not with stimulus neuron proportions.

Abstract representations reflect task

Our next analyses sought to address whether all contexts can be decoded, how well context representations generalized across different pictures or across time, and how they were related to stimulus representations. For each session, we computed the support vector machine (linear SVM) decoding accuracy of context during picture presentations (100–1,000 ms). Decoders were trained with either all neurons or all context neurons of each session (Fig. 3a). Confirming previous ANOVA results, decoding accuracies significantly exceeded chance levels of 0.2 (one out of five questions, two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test, uncorrected) for all contexts when all neurons were included (Psession = 1.981 × 10−3 and Ppatient = 4.094 × 10−3 for Bigger?; Psession = 9.142 × 10−7 and Ppatient = 6.430 × 10−4 for Last seen?; Psession = 5.187 × 10−3 and Ppatient = 3.861 × 10−2 for Older? or More expensive?; Psession = 1.456 × 10−3 and Ppatient = 6.624 × 10−3 for Like better?; Psession = 8.016 × 10−8 and Ppatient = 4.378 × 10−4 for Brighter?; and Psession = 4.378 × 10−4 and Ppatient = 4.378 × 10−4 for all contexts). Similar results were obtained when restricting these analyses to context neurons (Psession = 1.713 × 10−2 and Ppatient = 4.938 × 10−2 for Bigger?; Psession = 5.888 × 10−5 and Ppatient = 4.378 × 10−4 for Last seen?; Psession = 3.875 × 10−2 and Ppatient = 4.08 × 10−1 for Older? or More expensive?; Psession = 8.126 × 10−3 and Ppatient = 4.373 × 10−2 for Like better?; Psession = 9.826 × 10−7 and Ppatient = 4.368 × 10−4 for Brighter?; and Psession = 4.368 × 10−4 and Ppatient = 4.368 × 10−4 for all contexts). Although session-wise decoding accuracies were highest for Last seen? (0.292) and Brighter image? (0.303), they significantly exceeded chance for all contexts (0.229 for Bigger?, 0.234 for Older? or More expensive? and 0.257 for Like better?).

Abstract context representations invariant to picture identity or position combine with content representations across temporal gaps during picture presentations via context reactivation until context-dependent decisions. a, Population SVM-decoding accuracies of context (16 patients) during picture presentations comparing different questions (colours) using all versus only context neurons. b, Pooled context (green) or stimulus (red) decoding accuracies from context (left) and stimulus (right) neurons, for cross-validation or generalization across pictures (red), contexts (green) and serial picture positions (blue). c, A heat map of context decoding across time. The green diagonal line denotes identical training or testing times (see panel d). The dashed lines show event onsets (white) and offsets (yellow). The boxes indicate times analysed in panel e. d, Patient-wise context (top; green) or stimulus decoding (bottom; picture 1 or picture 2 in grey or lavender, respectively) and label-shuffled controls (red). Data are mean ± s.e.m. (solid lines and shaded areas, respectively), with dashed lines indicating chance. Significant differences (cluster permutation test, P < 0.01) from controls (top) or chance (below) are shown as solid lines below. Context decoding exceeded chance throughout, peaking after stimulus representations and remaining elevated. e, Patient-wise context-decoding accuracies trained with context neuron activity during questions (400 neurons per region) or baseline, and decoded during late first (red) or second (blue) picture presentations (boxes in panel c). The dashed line indicates chance. Question activity was reactivated during pictures, especially in the hippocampus. f, As in panel d, but before context-dependent decisions. Both context and content representations exceeded chance (dashed lines) until decisions (red line). CN, context neuron; SN, stimulus neuron. For the boxplots (a,b,e), quantile 1, median, quantile 3 and whiskers (points within ±1.5× the interquartile range) are shown, with the asterisks denoting differences from zero (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, uncorrected) or each other (Mann–Whitney U-test, uncorrected). ****P < 0.0001, ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01 and *P < 0.05.

Next, we assessed decoding performances from neurons pooled across sessions. To estimate their variance, random subsamples were drawn (see Methods). Pooled analyses yielded highly significant context (0.866, P = 1.708 × 10−6; green) and stimulus (0.995, P = 1.627 × 10−6; red) decoding accuracies (two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test against 0.2 or 0.25, uncorrected; Fig. 3b). In addition, we quantified generalization across stimuli, contexts or serial picture positions. When training and decoding contexts across different stimuli (0.764, P = 1.727 × 10−6) or picture positions (0.791, P = 1.716 × 10−6), accuracies remained highly significant. The same was true when stimuli were decoded across different contexts (0.995, P = 1.538 × 10−6) or picture positions (0.994, P = 1.638 × 10−6).

Subsequently, we computed context-decoding accuracies from binned population activity across different training and decoding periods during the trial (Fig. 3c; see Methods). Starting approximately 400 ms after question onset, context-decoding accuracies markedly exceeded chance (more than 20%; light blue or warmer colours) for most of the trial, peaking during question and late picture presentations. Consistent with previous analyses (Fig. 3b), training during first-picture presentations resulted in high decoding accuracies during second-picture presentations and vice versa, confirming generalized context representations. Figure 3d depicts patient-wise context-decoding accuracies of context neurons (top; green) for identical training and decoding times (green diagonal line in Fig. 3c) together with stimulus-decoding accuracies of pictures 1 and 2 by stimulus neurons (bottom; grey and lavender). Context-decoding accuracies (Fig. 3d, top) exceeded chance for the entire duration of the trial (solid green line; two-sided cluster permutation test, P < 0.01), even compared with label-shuffled controls (red line; two-sided cluster permutation test, P < 0.01). In parallel, stimulus neurons significantly encoded currently depicted pictures with high accuracies (Fig. 3d, bottom), as well as previous or even upcoming pictures (solid lines in grey and lavender). The latter was possible as second pictures could be inferred stochastically by design (probability of one-third instead of one-quarter due to no repetition). Of note, neural representations of first pictures were reactivated during second-picture presentations in all contexts (Extended Data Fig. 4), confirming that stimulus neurons encoded contents rather than question-related features. Furthermore, visual stimuli and contexts could be decoded simultaneously during picture presentations (first stimuli, then contexts) and with high accuracy even within single sessions (Extended Data Fig. 5). Context decoding across brain regions is shown in Extended Data Fig. 6. During question presentations, context decoding significantly exceeded chance (two-sided cluster permutation test, P < 0.01) in the parahippocampal cortex (turquoise), the entorhinal cortex (violet), the hippocampus (light blue) and even in the amygdala (mustard; P < 0.05). Context decoding was most accurate in the hippocampus (blue), particularly during picture presentations, exceeding chance in all four MTL regions.

Next, we determined whether activity patterns during question presentations were recapitulated during picture presentations (Fig. 3e). Session-wise SVM decoders were trained with regional context neuron activity either during question presentations (600–1,000 ms) or preceding baseline intervals (−500 to 100 ms), whereas contexts were decoded in the late phases of first (red; 600–1,000 ms) or second (blue; 600–1,000 ms) picture presentations. Training and decoding intervals correspond to the coloured boxes in Fig. 3c. To account for regional differences in the number of recorded neurons (1,051 in the amygdala, 482 in the parahippocampal cortex, 440 in the entorhinal cortex and 1,136 in the hippocampus), 400 neurons were randomly sampled per region. Decoders trained during questions, but not during preceding baselines (Fig. 3e, far left), significantly distinguished contexts during both subsequent picture presentations (Fig. 3e, right side; Wilcoxon signed-rank test, uncorrected) in the amygdala (Apicture 1: P = 1.953 × 10−2 and Apicture 2: P = 4.883 × 10−2), the entorhinal cortex (ECpicture 1: P = 3.906 × 10−3 and ECpicture 2: P = 5.469 × 10−2) and the hippocampus (Hpicture 1: P = 1.953 × 10−3 and Hpicture 2: P = 6.601 × 10−4), but not in the baseline control condition or in the parahippocampal cortex (BLpicture 1: P = 7.057 × 10−1 and BLpicture 2: P = 1; and PHCpicture 1: P = 4.316 × 10−1 and PHCpicture 2: P = 4.922 × 10−1).

Finally, we tested whether content and context representations of stimulus and context neurons persisted until the end of the trial when patients made context-dependent picture choices (Fig. 3f). Both context and picture contents could be decoded above chance until a decision was indicated (two-sided cluster permutation test, P < 0.01), with significantly enhanced decoding when choices matched ground truth (P = 0.0128 for context and P = 0.0351 for stimulus, one-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test; Extended Data Fig. 7).

Sequential activation arises during task

To assess whether pairing stimuli and contexts induced neuronal interactions or synaptic modifications reflecting stimulus–context associations, we computed shift-corrected, trial-by-trial cross-correlograms (see Methods) from pairs of mere (single main factor P < 0.001 in repeated-measures two-way ANOVA) stimulus and MC neurons during picture presentations from different MTL regions (Extended Data Figs. 8 and 9).

Only for pairs of neurons from the entorhinal cortex and the hippocampus of the same hemisphere (Fig. 4a and Extended Data Fig. 8) did firing of MS neurons (entorhinal MSs) predict firing of MC neurons (hippocampal MCs) after approximately 40 ms, as evidenced by asymmetric shift-corrected cross-correlograms (blue, peak on the left), but not that of other neurons (hippocampal ON; black, no prominent peaks). Cross-correlograms differed significantly between groups (that is, MS–MC versus MS–ON) on short timescales (−131 to −17 ms; two-sided cluster permutation test, P < 0.01 for neural pairs and P < 0.05 for sessions; Fig. 4a and Extended Data Fig. 8), but not for pairs from different regions (Extended Data Fig. 8) or across hemispheres (Extended Data Fig. 9). This is consistent with unidirectional synaptic changes reflecting stimulus–context associations. Of six sessions from four participants with simultaneous recordings of entorhinal stimulus and hippocampal context neurons, three (50%) from two participants (50%) exhibited significant cross-correlation peaks around −40 ms (cluster permutation test, P < 0.05).

a, Mean cross-correlograms (six sessions) during picture presentations between entorhinal MS and either hippocampal MC neurons (each with only one significant main effect, blue) or a matched number of other hippocampal neurons (non-significant, black; left). Data are mean ± s.e.m. (solid lines and shaded areas, respectively). The peak lag time is shown in the top left. The red horizontal lines indicate significant differences (P < 0.05, cluster permutation test). Stimulus–neuron firing in the entorhinal cortex predicted hippocampal context–neuron, but not other neuron firing after approximately 40 ms. The right panel is the same as the left panel, but with the region order reversed. The hippocampal stimulus neuron firing did not predict entorhinal context–neuron firing. b, Cross-correlations of all 40 entorhinal cortex stimulus and hippocampus context neuron pairs (MS–MC) before (pre, grey) and after (post, red) the experiment. Asymmetric correlations around −40 ms were absent before but emerged during the experiment and persisted afterwards (P < 0.01, cluster permutation test). c, Boxplots (quantile 1, median, quantile 3 and whiskers (points within ±1.5× the interquartile range) are shown) of mean cross-correlations (−10 to 100 ms; see dashed lines in b) between the same neuron pairs as in panel b (left). Correlations did not differ from zero before the experiment (exp.; P = 0.29, pre in grey; Wilcoxon signed-rank test), but exceeded zero during its first (exp., violet) and second (exp., blue) halves and after its termination (post, red; all P < 0.001). Correlations of all later periods exceeded pre-experiment levels (P(pre, exp1) = 3.258 × 10−2; P(pre, exp2) = 6.625 × 10−3; and P(pre, post) = 3.106 × 10−3). Firing rates did not differ significantly before and after the experiment but were significantly lower (P < 0.01) than during each experimental half (right). ****P < 0.0001, ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01 and *P < 0.05. All tests are two-sided and uncorrected.

Next, we analysed whether asymmetric cross-correlations between entorhinal MS and hippocampal MC neurons arise from pairings of stimuli with contexts and persist post-experiment. We computed cross-correlations during time windows before (Fig. 4b, grey) and after the experiment (Fig. 4b, red; see Methods). Strong asymmetric cross-correlation peaks were absent before the experiment, but present after its termination, differing significantly at −87 to −19 ms (P < 0.01, firing of MS predicts that of MC). Sequential firing therefore appeared to be associated with the experiment and to persist after its termination. We then quantified mean cross-correlation peaks from −100 to −10 ms throughout recordings (Fig. 4c, left). Mean cross-correlations did not differ significantly from zero (two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test) before (P = 2.889 × 10−1, pre in grey), but did both during the first (P = 2.036 × 10−5, exp. in violet) and second (P = 1.106 × 10−5, exp. in blue) half of the experiment and after its termination (P = 1.834 × 10−5, post in red). Cross-correlations in all subsequent time periods significantly exceeded pre-experiment levels (P(pre, exp1) = 3.258 × 10−2, P(pre, exp2) = 6.625 × 10−3 and P(pre, post) = 3.106 × 10−3, two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test). By contrast, mean firing rates (Fig. 4c, right) did not differ before and after the experiment (P(pre, post) = 4.103 × 10−1), but were significantly higher in its first and second half than before (P(pre, exp1) = 1.424 × 10−4 and P(pre, exp2) = 7.183 × 10−3) and after (P(post, exp1) = 3.244 × 10−3 and P(post, exp2) = 7.782 × 10−3).

Pre-activation predicts reactivation

We tested whether pre-activation of context neurons by preferred contexts (that is, questions) modulates their activity during subsequent picture presentations and their response likelihood following stimulus neuron activation.

First, we assessed whether normalized activity (baseline normalization; see Methods) of MC neurons during question presentations predicts activity during subsequent picture presentations (Fig. 5b and baseline control in Fig. 5c). Participant means of question (r = 0.46, P = 2.07 × 10−5), but not baseline activity (r = 0.03, P = 7.79 × 10−1) significantly (P < 0.01, Pearson correlation) predicted subsequent responses of MC neurons to picture presentations (Fig. 5b,c). The same results were obtained for all MC neurons (Extended Data Fig. 10a,b). Similarly, question activity of MC neurons predicted subsequent picture activity significantly more strongly than baseline activity trial by trial (Extended Data Fig. 10c). Specifically, participant means of Pearson correlation effect sizes were significantly higher for correlations between question and picture activity (r̄ = 0.12, left in green) than between baseline and picture activity (r̄ = 0.03, right in grey; P = 6.13 × 10−3, two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test). Next, we determined whether cross-correlations between stimulus and context neurons were affected by whether a preferred context (question with the strongest context neuron response) or a preferred stimulus (picture with the strongest stimulus neuron response) was presented (permutation test; see Methods). Cross-correlations between entorhinal MS and hippocampal MC neurons were significantly stronger on short (−66 to 28 ms) timescales when a preferred versus non-preferred context of context neurons was displayed (Fig. 5d; P < 0.01, two-sided cluster permutations test), but not when a preferred versus non-preferred stimulus of stimulus neurons (Extended Data Fig. 10d,f) was depicted. A schematic model relating these findings to stimulus–context association storage and retrieval is depicted in Fig. 5a.

a, Schematic model of stimulus–context storage. Activation of entorhinal cortical (EC) MS (red) and hippocampal (H) MC neurons (green) during trial events. Specific context neurons in the hippocampus respond to particular questions (coloured circles) and are reactivated during picture presentations (top left). Picture presentations elicit responses in selected stimulus neurons (numbers), whose activity predicts context neuron firing after approximately 40 ms (Fig. 4), strengthening connections encoding stimulus–context associations. Question response strengths predict context neuron activity and excitability (yellow triangles) during subsequent picture presentations (panels b,d; Extended Data Fig. 10a–c; lower left). Pre-activation by preferred contexts guides stimulus-driven pattern completion in hippocampal context neurons (right; dashed yellow line; panels d–f). b, Scatter plot of mean z-values for the five contextual questions during question versus picture presentations, computed per MC neuron and patient (5 questions × 16 patients, green stars in panel b and grey stars in panel c). Pearson correlations are visualized by regression lines. Question-evoked responses predict picture responses (r = 0.46, P = 2.07 × 10−5). c, As in panel b, but baseline versus picture presentations showing no correlation (r = 0.03, P = 0.78). d, Shift-corrected cross-correlations of EC-MS and H-MC during picture presentations after a preferred (maximum response, green) versus a non-preferred context (grey). The red horizontal lines indicate significant differences (P < 0.01, two-sided cluster permutation test). Data are mean ± s.e.m. (solid lines and shaded areas, respectively) with the dashed line indicating zero. MS firing predicts MC firing more strongly in preferred contexts. n = 40 neurons. e, Context SVM-decoding accuracy of H-MC trained with question and decoded with picture activity time locked (0–100 ms) to EC-MS firing (6 sessions: P = 0.031; 40 neuron pairs: P = 5.794 × 10−4; two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test). f, Context SVM decoding of H-MC distinguishing whether preferred (red) versus non-preferred (blue) pictures of the corresponding EC-MS were presented (6 sessions: P = 0.0156; 40 neuron pairs: P = 0.0338; one-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test). For the boxplots (e,f), quantile 1, median, quantile 3 and whiskers (points within ±1.5× the interquartile range) are shown; dashed lines indicate chance. *P < 0.05.

For further validation, we performed SVM-decoding analyses regarding the role of entorhinal stimulus and hippocampal context neuron interactions in stimulus-driven reinstatement of context. First, we computed session-wise context SVM-decoding accuracies of hippocampal MC neurons trained with question activity and decoded with subsequent picture activity (100–1,500 ms) time locked to entorhinal stimulus neurons firing (100-ms windows). Decoding accuracies slightly, but significantly, exceeded chance (0.21; Fig. 5e; 6 sessions: P = 0.03; 40 neuron pairs: P = 5.79 × 10−4; two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test). Second, we computed session-wise context SVM-decoding accuracies of hippocampal MC neurons for trials with preferred versus non-preferred pictures of the corresponding entorhinal stimulus neuron. Hippocampal MC neurons represented context more strongly when preferred (0.241) versus non-preferred (0.226) pictures of entorhinal stimulus neurons were presented (Fig. 5f; 6 sessions: P = 0.016; 40 neuron pairs: P = 0.034; one-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test).

Discussion

Contexts constrain which memories are relevant for future decisions15. Single neurons in the MTL represent both semantic content and context, that is, aspects of an episode1, such as tasks11, episodes13 or rules12. It remains unclear, however, how content and context are combined to form or retrieve integrated item-in-context memories in humans. In a context-dependent stimulus-comparison task, pairs of pictures were presented following a question that specified how the pictures were to be compared (Fig. 1a). Sixteen of seventeen participants remembered picture contents in their respective question context, showing consistent and transitive choices (Extended Data Fig. 1) closely matching objective ground truths (Extended Data Fig. 2). Analysing 3,109 neurons recorded from 16 neurosurgical patients, we found that co-activation of mostly separate populations of 597 stimulus-modulated neurons and 200 context-modulated neurons combined question and picture representations across temporal gaps. During picture presentations, when both representations became task-relevant, context neurons encoded question context, and stimulus neurons encoded picture contents (Fig. 3).

Context and content representations persisted until the trial ended, when participants selected one picture according to context (Fig. 3f), and were enhanced during behaviourally correct trials (Extended Data Fig. 7). During and after, but not before the experiment, firing of entorhinal stimulus neurons predicted hippocampal context neuron activity (Fig. 4a–c), consistent with storage of stimulus–context associations via spike-timing-dependent plasticity. Increased excitability of context neurons after pre-activation by their preferred context suggested a gating mechanism of stimulus-driven pattern completion in the hippocampus (Fig. 5a,d) that enhanced context representations (Fig. 5f). This implies that stimulus and context neurons contribute to context-dependent stimulus processing via reinstatement of context (Figs. 3e and 5e,f). Their co-activation could support memory of stimuli within their context and refine content processing according to context. The generality of the representations of both populations (Fig. 3b) appears well suited to support flexible decision-making by broadening or constraining memories through reinstatement or co-activation. Conjunctive representations of stimulus–context, conversely, reflected limited pattern separation in humans and may specify item-in-context or their attributes.

Operationalization of context

Contexts include independent elements (encoded alongside contents without altering processing) and interactive elements that influence content processing14. For example, evaluating the price of a melon in a supermarket versus its taste at home illustrates interactive context effects. Our task operationalizes interactive contexts, as questions define comparison rules that shape stimulus processing16. Behaviourally, we successfully captured these effects as pictures were ranked differently across questions (median Kendall’s W = 0.232) yet consistently and transitively within questions, tracking objective ground truths (mean ρ = 0.760; Extended Data Fig. 2), which is not expected for fixed stimulus-value judgements. Neural data reflected both interactive contexts and the contents that they acted on. First, stimulus neurons represented picture contents rather than isolated features, as evidenced by consistent encoding across contexts (Fig. 3b) and reactivation of first-picture representations during second-picture presentations for all questions (Extended Data Fig. 4), not only for feature-relevant questions. Second, context neurons encoded interactive context rather than transient attention, distinguishing questions before stimulus onset (Figs. 3d and 5b and Extended Data Fig. 10a,c), reinstating representations during picture viewing (Figs. 3e and 5e), and maintaining them until the decision (Fig. 3f). Supporting their functional relevance, both context and stimulus decoding were higher on correct trials (Extended Data Fig. 7). Although the task captures how interactive context shapes memory processing, future studies should examine these mechanisms under independent context manipulations and in naturalistic settings.

Content and context across the MTL

The MTL is thought to contain parallel streams of content and context converging in the hippocampus, enabling mutual cuing of contents and context17,18. In this view, neocortical context representations are processed via the parahippocampal cortex or medial entorhinal cortex, and content representations via the lateral entorhinal cortex or perirhinal cortex before convergence in the hippocampus17. Approximately 6% of MTL neurons strongly encoded context during picture presentations. Consistent with the literature, context representations were more frequent in the parahippocampal cortex, entorhinal cortex and hippocampus than in the amygdala, and were highest among hippocampal stimulus neurons (21.26%). Although the large majority of stimulus neurons (88%) were invariant to context, and most context neurons (63.5%) were invariant to stimulus, a small but significant fraction of stimulus neurons represented either both or specific conjunctions of context and stimulus, particularly in the hippocampus (Fig. 2b–d). Conjunctive representations were most abundant in the hippocampus (2.29%), particularly among stimulus neurons (10.34%). Consistent with this, stimulus–context neurons were more prevalent in sessions with higher proportions of both stimulus and context neurons in the hippocampus and amygdala, but only with higher context neuron proportions in the parahippocampal and entorhinal cortices (Extended Data Fig. 3). These regional patterns support the convergence of parallel content and context streams in the hippocampus, where they may create conjunctive representations. Nevertheless, distinct representations remained most prevalent. The context invariance of most stimulus neurons (Fig. 2a,e) is notable given potential attentional fluctuations across questions. Although stimulus neurons were overrepresented due to pre-selection of response-eliciting pictures, this did not bias (but rather supported) context invariance, as stimulus representations persisted from pre-screenings to main experiments (Extended Data Fig. 11).

In our paradigm, questions provided contextual constraints for relevant information (for example, value information from the amygdala19 for Like better?) about stimuli that were to be related to each other and to serial picture positions. The MTL, and particularly the hippocampus, has been associated with such relational processing. Lesions cause relational memory deficits, in both long-term20 and working21,22 memory, impair the ability to imagine details in hypothetical contexts23,24,25 and disrupt episodic memory26. Through pattern completion, inputs from the entorhinal cortex (representing content) are thought to be complemented in the hippocampal formation (thereby retrieving associated context)27. Supporting this view, during and after, but not before experimental pairing of stimuli and context, firing of entorhinal stimulus neurons predicted hippocampal context neuron activity after tens of milliseconds. Picture presentations served as cues for the recall of both content (from the current or the preceding picture) and context (the relevant question). Correspondingly, representations of current visual stimuli were followed by reinstatement of previous stimuli or contexts. Synaptic modifications of direct or indirect connections offer one potential explanation and could be tested by pairing only subsets of contents and contexts, which should produce cross-correlation changes only in corresponding neuron pairs. Furthermore, electrostimulation of hippocampal context neurons during context reactivation peaks following stimulus representations (Fig. 3d) should disrupt cross-correlations, reinstatement patterns and behaviour. In addition, increased excitability of context neurons suggests a gating mechanism of stimulus-driven pattern completion. After repeated pairings of contents and contexts strengthen connections between entorhinal stimulus neurons and multiple hippocampal context neurons, stimulus neuron firing could preferentially activate context neurons pre-activated by their preferred question. This could be tested by modulating context neuron excitability during question presentations via electrostimulation or attention. However, as the exact placement of microwires within a target region cannot be determined reliably with the noninvasive imaging methods available in humans, it remains uncertain whether hippocampal microwires were recorded from the CA1/CA3 region, the dentate gyrus or the subiculum.

Overall, experiment-induced neural interactions between distinct neuronal populations may support memory of stimuli in context. Their resulting co-activations could guide contextual memory processing of stimuli, for example, via indexing of brain areas that contain context-specific stimulus information.

Contextual memory search

Neural representations of content28,29,30 and context31,32,33,34 are reinstated during memory search and potentially serve as memory indices. In humans, stimulus neurons in the MTL encode semantic content29,35,36 and are reactivated during recall of their preferred stimulus, that is, concept28,29,30. Other neurons encode contextual features such as rules12, or episodic boundaries13 or task instructions11. Moreover, ensemble activity during recognition memory reinstates contextual neural states13. However, it remains unclear whether distinct neuronal populations simultaneously reinstate content and context during context-dependent relational memory processing. Context neurons encoded question context throughout trials, with decoding peaking at question onset and during late picture phases when content needed to be processed according to context. Context neuron representations also generalized across stimulus identities and serial picture positions, with decoding accuracies exceeding chance even when SVM decoders were trained on activity during specific pictures or picture positions and tested on the remaining ones. In addition, response patterns to question context were reinstantiated during the late phase of picture presentations, particularly in the entorhinal cortex and hippocampus. Overall, the simultaneous (re-)instatement of both context and content at retrieval-related latencies37, together with the generalization of their representations, suggests that they contribute to memory search.

Pattern separation and human cognition

The balance between memory specificity and generalization is fundamental to adaptive cognition. Besides declarative memories, the MTL is essential for decision-making15,38 and abstract human cognition such as generalization7, deliberation38 or inference39. In rodents, hippocampal neural representations often indicate conjunctions of stimuli and are context dependent3,4. This ‘pattern separation’, that is, the creation of distinct neural codes for similar inputs, renders memory representations distinguishable. By contrast, in humans, selective concept neurons reliably encode stimulus content across contexts11,40 and may constitute building blocks of memory41. Their context invariance and lack of pattern separation5 (but see ref. 9) may enable knowledge generalization across contexts (at the expense of ‘semantic deviations’ leading to false memories)36.

Abstract content representations36 appear well suited for a broad generalization across contexts. However, contexts also constrain which memories are relevant42,43. Recalling items from studied word lists enhances the recall of items in temporal or semantic proximity43, an effect that correlates with memory performance and general cognitive ability44. Moreover, items are more readily recalled when sharing encoding contexts, such as task instructions or video clips13.

Our MTL neurons showed a low but detectable degree of pattern separation (stimulus–context interaction neurons in the hippocampus), supporting both generalization and differentiation of content and context. Consistent with previous reports11,40, stimulus neuron activity reliably distinguished picture identity irrespective of context, and reflected picture-specific memories, as evidenced by consistent first-picture reactivations during second-picture presentations across all contexts (Extended Data Fig. 4). In addition, we identified neurons that represented context independent of picture identity or position. The invariance of both populations allows us to generalize memories, whereas their co-activation could differentiate otherwise overlapping memories. Although co-activation may narrow memory searches, reinstatement of associated contexts via pattern completion could render additional memories associated with this context more accessible and thereby promote generalization1. A combinatorial indexing scheme of this kind would support flexible decision-making and potentially reduces the need for explicit pattern-separated, conjunctive representations.

Methods

Patients and recording

All studies were approved by the Medical Institutional Review Board at the University of Bonn (accession number 095/10 for single-unit recordings in humans in general and 248/11 for the current study in particular). Each patient gave informed written consent both for the implantation of microwires and for participating in the experiment. We recorded from 17 patients with pharmacologically intractable epilepsy (9 male patients; 22–65 years of age), implanted with intracranial electrodes to localize the seizure onset zone for surgical resection45. Each depth electrode contained a microwire bundle consisting of nine microwires, consisting of a reference electrode with low impedance and eight high-impedance recording electrodes (AdTech), which protruded from the tip of the electrode by approximately 4 mm. All bundles were localized using a post-implantation CT scan co-registered with a pre-implantation MRI scan normalized to Montreal Neurological Institute space. The differential signal from the microwires was amplified using a Neuralynx ATLAS system, filtered between 0.1 Hz and 9,000 Hz, and sampled at 32 kHz. These recordings were stored digitally for further analysis. Our original dataset consisted of 50 experimental sessions from 17 patients with recordings from the amygdala, parahippocampal cortex, entorhinal cortex and hippocampus. One session from one patient was excluded due to low behavioural performance, resulting in a final sample of 49 sessions from 16 patients. The excluded session stemmed from the only patient for which no context neurons could be detected (others exhibited an average of 12.5). For most patients, ten microwire bundles (median of 80 channels) were placed with an average of 69.34 recorded channels (range of 32–80) and a neuron yield of 0.92 per channel. Each experimental session was recorded after a screening for visually selective responses in the morning of the same day. The mean (±s.d.) time interval between screenings and subsequent experiments was 4.71 ± 2.02 h (range of 1.40–9.15 h). In 13 of the 16 patients, more than one session was recorded. The mean (±s.d.) time interval between multiple sessions was 46.94 ± 24.19 h (range of 16.57–118.06 h). Neural dependence across 33 consecutive pairs of these sessions was assessed using intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs(2,1))46,47. ICCs were computed across channels (that is, microwires), separately for context and stimulus neurons. ICCs quantify cross-session stability, with lower values indicating weaker dependence. Observed ICCs were compared with null distributions obtained by permuting channels. ICCs did not strongly exceed these null distributions (Hedges’ g: stimulus = 0.3415; context = 0.1568) and only reached significance (α = 0.01) in 7 of 33 consecutive stimulus neuron session pairs, 3 of 31 consecutive context neuron session pairs, and in no session pair for both, all with low overall effect sizes (Extended Data Fig. 12). We used the spike-sorting software Combinato48 with default parameters for the exclusion of noisy recording channels, artefact removal, spike detection and spike sorting. Afterwards, we manually removed remaining artefacts, merged potentially over-clustered units from the same channel and distinguished single from multi-units using the graphical user interface in Combinato. Highly similar spike shapes, inter-spike interval distributions, neural responses to visual stimuli, asymmetric cross-correlations and the absence of neural activity during refractory periods guided this procedure, which predated all further analyses.

Experimental design

The paradigm was performed on a laptop computer with the psychtoolbox3 (www.psychtoolbox.org) and octave (www.octave.org/) running on a Debian 8 operating system (www.debian.org) for stimulus delivery. Before the experiment, approximately 100 pictures of people, animals, scenes and objects were presented on a laptop screen in pseudo-random order (presentation for 1 s; 6 or 10 trials). Then, after automatic spike extraction and sorting with Combinato, neural responses to these pictures were evaluated based on raster plots and histograms. The aim of this procedure was to identify a subset of four pictures for the following experiment while maximizing the number of neurons that were expected to respond selectively to only one of the pictures. These four pictures were then presented in the experiment. Each self-triggered trial contained one out of five questions, a sequence of two of four pictures with jittered onsets, and an answer prompt displaying 1 or 2?. Patients indicated the sequential position of the picture that best answered the question by pressing key 1 or 2. We resolved ambiguous meanings of each depicted picture before the experiment and elaborated on the meaning of each question in a short test run of the paradigm. The questions were Bigger? (volume), Last seen in real life?, More expensive? or Older? (if the pictures set included a person), Like better? and Brighter?. Patients were instructed to try to stick to one answer for a given picture pair, but to keep mentally computing the answer to each question in the course of the experiment. In total, the experiment consisted of 300 trials in which each of the 5 questions and all 12 possible ordered picture pairs out of 4 pictures were presented equally often and in an unpredictable pseudo-random order. This resulted in 60 trials per question, 25 trials per picture pair and 5 trials per specific combination of question and picture pair.

Definition of neural populations

For each unit, repeated two-way repeated-measures ANOVAs with factors stimulus (picture), context (question) and interactions were computed from the activity during picture presentations (100–1,000 ms) at an α-level of 0.001. Units with (at least) a significant main effect of stimulus or context are referred to as stimulus or context neurons, respectively. If a unit only (at most) showed a significant main effect of either stimulus or context, it is termed a MS or a MC neuron, and if both main effects were significant, it is called a contextual stimulus neuron. Conversely, stimulus–context interaction neurons were defined by the presence of a significant interaction. We determined whether the observed number of neurons pertaining to each of these populations or all effect sizes exceeded chance in the following manner. First, the probability of obtaining observed numbers of significant neurons was assessed for each population separately by binomial tests with an expected false-positive probability of 0.001 corresponding to the α-level above. Second, to account for potential statistical dependencies between factors or neurons, repeated-measures ANOVA effect sizes of all neurons were compared with stratified label-shuffling controls, irrespective of statistical significance (Fig. 2e, see insets). Specifically, null distributions of partial η2 were obtained either by permuting picture labels for each question separately (factor stimulus) or question labels for each picture separately (factor context or stimulus–context interaction). Afterwards, effect sizes of data and controls were averaged for each patient (see Fig. 2e in lavender and grey) and their distributions compared (two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test, Bonferroni corrected). To additionally account for patient-level variability, we fit separate linear mixed-effects models for each ANOVA factor across all recorded neurons. Each model included a fixed intercept (capturing grand population effect size differences) and patient-specific random intercepts. Neural populations remained largely consistent, regardless of whether they were identified via label-shuffled ANOVA effect sizes or analytical ANOVA P values.

To assess the stability of stimulus representations across pre-screenings and main experiments, SVM decoders were trained on main experiment activity and tested either on pre-screening (across) or main experiment activity (within, leave-out cross-validation with matched trial counts). For 45 recording sessions, all four pictures of the main experiment were part of the pre-screening before the experiment. Picture-decoding accuracies highly exceeded chance, particularly for microwire channels that did versus did not contain stimulus neurons (Extended Data Fig. 11). There were no significant differences in decoding accuracy when testing on pre-screening data (across) or on main experiment activity (within), both for stimulus neuron channels and for non-stimulus neuron channels (two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test). Finally, Spearman correlations were computed between stimulus–context neuron proportions and stimulus or context neuron proportions across all session-site combinations (n = 168; Extended Data Fig. 3). Site-specific correlations were assessed using permutation tests (1,000 permutations of stimulus–context proportions, one-sided test for positive associations).

SVM population decoding

Linear SVM-decoding accuracies of context were computed from session-wise population activity of context neurons (Fig. 3a,c,d,f; see Fig. 3a for decoding from all neurons) and averaged for each patient, except in Fig. 3b in which a pooled decoding scheme was used (30 random subsamples of 151 stimulus or context neurons, corresponding to 75% of context neurons, were drawn to estimate variance). Figure 3a depicts these accuracies for each context separately. In general, decoders were implemented with functions from the LIBSVM library (v3.24) using standard parameters (unless stated otherwise) in custom scripts written in MATLAB R2021a or Python (scikit-learn 0.24.1), and a fivefold cross-validation scheme without overlap between training and testing data was used with five repetitions. Generalization of context decoding across picture identities (Fig. 3b, left in red), of stimulus decoding across contexts (Fig. 3b, right in green) or of either decoding across serial picture positions (in blue) was assessed. This was achieved by training with activity in response to each picture, each picture–context or each picture–position and decoding during the respective remaining ones. Training was performed either during picture presentations (Fig. 3a,b; 100–1,000 ms), question presentations (Fig. 3e) or during the course of the experiment (Fig. 3c,d,f; see below). Thus, obtained decoding accuracies were statistically compared with chance (one-fifth for context and one-quarter for visual stimuli; two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test in Fig. 3a,e; two-sided cluster permutation tests P < 0.01 in Fig. 3d,f) or to each other (Mann–Whitney U-test in Fig. 3a; and two-sided cluster permutation tests in Fig. 3d).

Session-wise context-decoding accuracies computed from binned population activity (400 ms, stride = 100 ms) at differing training and decoding times throughout the trial of all context neurons were visualized as a heat map (Fig. 3c). Context-decoding accuracies from identical decoding and training times (diagonals) were then plotted with standard errors for all 16 patients with context neurons (Fig. 3d, top in green) and compared with a label-shuffling control condition (Fig. 3d, top red). The latter was obtained by randomly permuting question context labels for each session before training and decoding. Time periods of significant differences of decoding accuracies from real data and controls were evaluated with a cluster permutation test (Fig. 3d, solid line below). Specifically, paired-samples Student’s t-tests (two-sided) were computed for each time bin (α = 0.01) to determine clusters of contiguous decoding accuracy time bin differences. Sums of t-values within each cluster were assessed relative to the null distribution of t-value sums obtained from 1,000 permutations of data and control labels (or chance levels, see below). If t-value sums fell into the top percentile of the permutation distribution, differences during the time period of the respective cluster were considered significant. Decoding accuracies of either first (Fig. 3d, bottom in grey) or second pictures (Fig. 3d, bottom in lavender) obtained by patient-wise training and decoding with the activity of stimulus neurons in the course of the experiment were plotted and compared with chance (one-quarter) in an analogous manner (Fig. 3d, bottom). In addition, we examined whether neural activity patterns of stimulus neurons reflected content rather than feature representations (Extended Data Fig. 4). Session-wise linear SVMs were trained on stimulus neuron activity (400–800 ms after first-picture onset) to decode first picture identities from neural activity throughout second picture presentations (400-ms bins, stride = 100 ms) for each of the five question contexts. Statistical significance across sessions was assessed using cluster-based, two-sided permutation tests against chance (α = 0.05, chance = one-quarter).

Afterwards, decoding performances of context were further analysed for each brain region separately (Extended Data Fig. 6). Furthermore, we determined whether activity patterns associated with the presentation of question instructions were recapitulated during picture presentations (Fig. 3e). For this purpose, patient-wise SVM decoders were trained with regional context neuron activity either during question presentations (600–1,000 ms) or preceding baseline intervals (−500 to 100 ms), whereas contexts were decoded in the late phases of first (red; 600–1,000 ms) or second (blue; 600–1,000 ms) picture presentations. Specifically, a random subset of neurons (n = 400) was repeatedly drawn (n = 30) from each brain region. Afterwards, decoding accuracies were averaged for each patient if context neurons were part of the drawn subsets before averaging across repetitions. The deviation of the resulting patient-wise distributions of decoding accuracies from chance (one-fifth) was assessed by means of two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank tests (uncorrected).

Finally, we assessed decoding accuracies of stimulus and context neurons preceding the end of the trial when one picture was chosen over the other according to context. Again, patient-wise SVM-decoding accuracies of contents and context were computed from the activity of stimulus and context neurons, respectively, and compared with chance (Fig. 3f; two-sided cluster permutation tests P < 0.01).

Interaction analyses between populations

Session-wise cross-correlations were computed for pairs of MS–MC pairs (each with only one main effect P < 0.001 in repeated-measures two-way ANOVA) for different brain regions on a trial-by-trial basis during picture presentations (Fig. 4a and Extended Data Figs. 8 and 9 with neuron pairs; 0–1,500 ms after picture onsets) or during different contiguous time windows (Fig. 4b,c with neuron pairs; before, after or in the first and second half of the experiment). Each cross-correlogram was normalized according to its window length and the mean firing rate of its neural pair, and then convolved with a Gaussian kernel (sigma = 10 ms). To capture stimulus-independent interactions, normalized cross-correlations from non-simultaneous activity of the same pairs (shift predictors) were subtracted from the former. Shift predictors were obtained either by randomly permuting activity patterns of one of the neurons across relevant trials (Figs. 4a and 5d,e and Extended Data Figs. 8 and 9) or by randomly shifting spike trains in time (up to 10,000 ms). For the evaluation of effect sizes, analogous shift-corrected cross-correlations (noise correlations) were computed for a matched number of MS and other neurons (MS–ON pairs) defined by their lack of stimulus and/or context modulation (Pstimulus > 0.01, Pcontext > 0.01 and Pstimulus–context > 0.01 in repeated-measures two-way ANOVA). For three sessions, in which matching failed due to a sparsity of other neurons, randomly chosen other neurons from the same brain region were used instead. Cross-correlograms between MS and MC neurons or their session averages were then compared with these controls by means of two-sided cluster permutations tests (P < 0.01; Fig. 4a,b and Extended Data Figs. 8 and 9). For analyses in Fig. 4b,c, the largest possible symmetric time windows immediately before and after the experiment were used. The duration of these time windows (range of 16.57–106.05 s, mean of 48.79 s) either amounted to the time between the first recorded spike and the beginning of the experiment, or between the end of the experiment and the last recorded spike for each neuron pair (entorhinal MS–hippocampal MC pairs) depending on which was smallest. Afterwards, mean cross-correlations at small negative lags (MS followed by MC firing; averaged between −10 to −100 ms) as well as all mean firing rates of each neuron pair were compared against zero or against each other in different phases of the experiment (two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank tests; Fig. 4c). In addition, cross-correlations during picture presentations (0–1,500 ms) were re-computed depending on whether preferred contexts of hippocampal MC neurons or preferred stimuli of entorhinal MS neurons were presented (P < 0.01, two-sided cluster permutations tests; Fig. 5d and Extended Data Fig. 10d–f). Preferred versus non-preferred contexts or stimuli were defined as the question or stimulus that elicited the strongest neural response in each context or stimulus neuron during picture presentations (0–1,000 ms) versus a randomly drawn different question or stimulus. As a further validation of this model, two additional SVM interaction-decoding analyses were performed. First, decoders were trained with hippocampal MC neuron activity per session during question presentations and decoded with their activity during subsequent picture presentations (100–1,500 ms) time locked to entorhinal MS neurons firing (in 100-ms windows after each entorhinal MS action potential). Second, decoders were trained with hippocampal MC neuron activity per session for trials during which the preferred versus non-preferred pictures of the corresponding entorhinal stimulus neuron were presented.

Next, Pearson correlations between (patient means of) the mean question-wise activity of MC neurons during question presentations (500–1,300 ms; Fig. 5b and Extended Data Fig. 10a) or its baseline (−700 to 100 ms; Fig. 5c and Extended Data Fig. 10b) versus subsequent picture presentations (500–1,300 ms) were computed (P < 0.01), normalized to baseline and visualized as scatter plots with regression lines (Fig. 5b,c and Extended Data Fig. 10a,b). Finally, Pearson correlation effect sizes were computed for each MC neuron from activity between question and subsequent picture presentations or between baseline and subsequent picture presentations across all trial conditions (60 combinations of 5 questions and 12 picture pairs) and averaged per patient. Afterwards, effect sizes of both conditions were compared and visualized as boxplots (two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test; Extended Data Fig. 10c).

Behavioural performance

Memory of contents (that is, pictures) in context (that is, after a particular question) was evaluated by determining the consistency and transitivity of the answers that were provided at the end of each trial. Consistency (γ) captures the degree to which preference for one picture over another was maintained when the presentation order was reversed. A picture was considered to be preferred if it was chosen in at least three out of the five trials that it was paired with a specific other picture in a given temporal order and context. If this picture was preferred both when it was shown first or second (chosen at least 3 out of 5 times in each order), all 10 trials were assigned a consistency value of 1 instead of 0. The overall consistency of a session was computed by averaging the consistency values of zeros and ones across all 300 trials. For random choices, a consistency of 0.5 is expected (Extended Data Fig. 1a).

Transitivity (τ) captures the logical consistency of preferences across three pictures (x, y, z) when considered in pairs. For each of the four unordered picture triples, we computed preference probabilities P(x > y), P(y > z) and P(x > z) for all three unordered picture pairs based on how many times out of the 10 trials one picture was chosen over the other in a given context. A triple was considered transitive if preference probabilities satisfied the condition of weak stochastic transitivity: P(x > y) ≥ 0.5 and P(y > z) ≥ 0.5, then P(x > z) ≥ 0.5. This condition was tested for all permutations of x, y and z and a transitivity value of 1 instead of 0 was assigned to the triple if the condition was satisfied for any permutation. For random choices, a transitivity of 0.75 is expected (Extended Data Fig. 1a). Finally, context dependence of performance was assessed by deriving an overall behavioural performance measure from mean of consistency (γ) and transitivity (τ) values per question of each session and comparing them across contexts (Kruskal–Wallis test, α = 0.05; Extended Data Fig. 1b). Moreover, for questions with objective ground truths (Bigger?, and More expensive? or Older?), we validated behavioural performance by computing Spearman correlations between behaviourally determined picture ranks and objectively determined picture ranks, averaged across available questions per session. Session-wise correlations were tested against zero using a Wilcoxon signed-rank test, and the observed mean across sessions was compared with a null distribution generated from 1,000 permutations of picture ranks within each session–question pair (Extended Data Fig. 2). In addition, decoding accuracies were related to behavioural performance by comparing correct trials (in which behavioural choices matched ground-truth picture rankings) versus incorrect trials (in which choices deviated from ground truth). Session-wise linear SVMs (fivefold cross-validation, five repeats) were trained on context, stimulus or stimulus–context neuron activity during picture presentations (100–1,000 ms) to decode questions, pictures and picture–question combinations, respectively. Decoding accuracies for correct versus incorrect trials were compared using one-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank tests (correct > incorrect; α = 0.05). Chance levels were one-quarter for stimulus, one-fifth for context and one-twentieth for stimulus–context decoding (Extended Data Fig. 7).

Statistics and reproducibility

Forty-nine sessions from 16 participants were analysed (one session of one participant was excluded based on a low behavioural performance). A total of 200 context neurons were detected in 38 sessions from the 16 participants. Twenty-five sessions contained at least 3 stimulus and context neurons each, 12 sessions more than 5.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available on GitHub (https://github.com/mabausch/ContentContextNeurons.git).

Code availability

All code related to the analyses of the article is available on GitHub (https://github.com/mabausch/ContentContextNeurons.git).

References

Yonelinas, A. P., Ranganath, C., Ekstrom, A. D. & Wiltgen, B. J. A contextual binding theory of episodic memory: systems consolidation reconsidered. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 20, 364–375 (2019).

Eichenbaum, H., Yonelinas, A. P. & Ranganath, C. The medial temporal lobe and recognition memory. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 30, 123–152 (2007).

O’Keefe, J. & Krupic, J. Do hippocampal pyramidal cells respond to nonspatial stimuli?. Physiol. Rev. 101, 1427–1456 (2021).

Kubie, J. L., Levy, E. R. J. & Fenton, A. A. Is hippocampal remapping the physiological basis for context? Hippocampus https://doi.org/10.1002/hipo.23160 (2019).

Quiroga, R. Q. No pattern separation in the human hippocampus. Trends Cogn. Sci. 24, 994–1007 (2020).

Zeithamova, D. & Bowman, C. R. Generalization and the hippocampus: more than one story? Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 175, 107317 (2020).

Kumaran, D., Summerfield, J. J., Hassabis, D. & Maguire, E. A. Tracking the emergence of conceptual knowledge during human decision making. Neuron 63, 889–901 (2009).

Quiroga, R. Q. Concept cells: the building blocks of declarative memory functions. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 13, 587–597 (2012).

Suthana, N., Ekstrom, A. D., Yassa, M. A. & Stark, C. Pattern separation in the human hippocampus: response to Quiroga. Trends Cogn. Sci. 25, 423–424 (2021).

Polyn, S. M. & Kahana, M. J. Memory search and the neural representation of context. Trends Cogn. Sci. 12, 24–30 (2008).

Minxha, J., Adolphs, R., Fusi, S., Mamelak, A. N. & Rutishauser, U. Flexible recruitment of memory-based choice representations by the human medial frontal cortex. Science 368, eaba3313 (2020).

Kutter, E. F., Boström, J., Elger, C. E., Nieder, A. & Mormann, F. Neuronal codes for arithmetic rule processing in the human brain. Curr. Biol. 32, 1275–1284.e4 (2022).

Zheng, J. et al. Neurons detect cognitive boundaries to structure episodic memories in humans. Nat. Neurosci. 25, 358–368 (2022).

Baddeley, A. D. Domains of recollection. Psychol. Rev. 89, 708–729 (1982).

Bornstein, A. M. & Norman, K. A. Reinstated episodic context guides sampling-based decisions for reward. Nat. Neurosci. 20, 997–1003 (2017).

Polyn, S. M., Norman, K. A. & Kahana, M. J. Task context and organization in free recall. Neuropsychologia 47, 2158–2163 (2009).

Eichenbaum, H., Sauvage, M., Fortin, N., Komorowski, R. & Lipton, P. Towards a functional organization of episodic memory in the medial temporal lobe. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 36, 1597–1608 (2012).

Davachi, L. Item, context and relational episodic encoding in humans. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 16, 693–700 (2006).

Mormann, F., Bausch, M., Knieling, S. & Fried, I. Neurons in the human left amygdala automatically encode subjective value irrespective of task. Cereb. Cortex 29, 265–272 (2019).

Squire, L. R. Memory for relations in the short term and the long term after medial temporal lobe damage. Hippocampus 27, 608–612 (2017).

Konkel, A. & Cohen, N. J. Relational memory and the hippocampus: representations and methods. Front. Neurosci. 3, 166–174 (2009).

Hannula, D. E., Tranel, D. & Cohen, N. J. The long and the short of it: relational memory impairments in amnesia, even at short lags. J. Neurosci. 26, 8352–8359 (2006).

Hassabis, D., Kumaran, D., Vann, S. D. & Maguire, E. A. Patients with hippocampal amnesia cannot imagine new experiences. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 1726–1731 (2007).

Rosenbaum, R. S., Gilboa, A., Levine, B., Winocur, G. & Moscovitch, M. Amnesia as an impairment of detail generation and binding: evidence from personal, fictional, and semantic narratives in K.C. Neuropsychologia 47, 2181–2187 (2009).

Maguire, E. A. & Hassabis, D. Role of the hippocampus in imagination and future thinking. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, E39–E39 (2011).

Dickerson, B. C. & Eichenbaum, H. The episodic memory system: neurocircuitry and disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology 35, 86–104 (2010).

Teyler, T. J. & Rudy, J. W. The hippocampal indexing theory and episodic memory: updating the index. Hippocampus 17, 1158–1169 (2007).

Gelbard-Sagiv, H., Mukamel, R., Harel, M., Malach, R. & Fried, I. Internally generated reactivation of single neurons in human hippocampus during free recall. Science 322, 96–101 (2008).

Bausch, M. et al. Concept neurons in the human medial temporal lobe flexibly represent abstract relations between concepts. Nat. Commun. 12, 6164 (2021).

Ison, M. J., Quiroga, R. Q. & Fried, I. Rapid encoding of new memories by individual neurons in the human brain. Neuron 87, 220–230 (2015).

Kragel, J. E. et al. Distinct cortical systems reinstate the content and context of episodic memories. Nat. Commun. 12, 4444 (2021).

Manning, J. R., Polyn, S. M., Baltuch, G. H., Litt, B. & Kahana, M. J. Oscillatory patterns in temporal lobe reveal context reinstatement during memory search. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 12893–12897 (2011).

Staresina, B. P. et al. Recollection in the human hippocampal–entorhinal cell circuitry. Nat. Commun. 10, 1503 (2019).

Folkerts, S., Rutishauser, U. & Howard, M. W. Human episodic memory retrieval is accompanied by a neural contiguity effect. J. Neurosci. 38, 4200–4211 (2018).

Quiroga, R. Q., Reddy, L., Kreiman, G., Koch, C. & Fried, I. Invariant visual representation by single neurons in the human brain. Nature 435, 1102–1107 (2005).

Reber, T. P. et al. Representation of abstract semantic knowledge in populations of human single neurons in the medial temporal lobe. PLoS Biol. 17, e3000290 (2019).

Staresina, B. P. & Wimber, M. A neural chronometry of memory recall. Trends Cogn. Sci. 23, 1071–1085 (2019).

Shadlen, M. N. & Shohamy, D. Decision making and sequential sampling from memory. Neuron 90, 927–939 (2016).

Shohamy, D. & Daw, N. D. Integrating memories to guide decisions. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 5, 85–90 (2015).

Rey, H. G. et al. Lack of context modulation in human single neuron responses in the medial temporal lobe. Cell Rep. 44, 115218 (2025).

Mackay, S. et al. Concept and location neurons in the human brain provide the ‘what’ and ‘where’ in memory formation. Nat. Commun. 15, 7926 (2024).

Healey, M. K. & Uitvlugt, M. G. The role of control processes in temporal and semantic contiguity. Mem. Cognit. 47, 719–737 (2019).