Abstract

Vertebrate vision is mainly accommodated by a pair of lateral image-forming camera-type eyes and is supplemented in non-mammalian vertebrates by a dorsal pineal complex (pineal and parapineal organs) functioning as photoreceptive and/or endocrine organs1. The pineal complex shares a common genetic and embryological basis with the lateral eyes, both derived from evaginations during the development of diencephalon2. Despite being widely heralded as the ‘third eye’ in crown vertebrates3, the nature of the pineal complex and its presumed visual capability in early vertebrates2 remain unknown. Here we describe two pigmented features situated between the lateral eyes in two species of myllokunmingids, the earliest known fossil vertebrates (approximately 518 million years ago), and interpret these as pineal/parapineal organs. In both myllokunmingid species, the pineal complex contains abundant melanin-containing melanosomes identical to those in the retinal pigment epithelium in the lateral eyes, together with a distinctive, regularly ovoid structure interpreted as a lens. Our results indicate that the lateral eyes and pineal complex in myllokunmingids probably functioned as camera-type eyes capable of image formation. Thus, we propose that the four camera-type eyes represent an ancestral vertebrate character, corroborating hypotheses about the deep homology between the eyes and pineal complex.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All supporting data of this study are available at Figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29589761).

References

Eakin, R. M. The Third Eye (Univ. of California Press,1973).

Lamb, T. D. Evolution of phototransduction, vertebrate photoreceptors and retina. Prog. Retinal Eye Res. 36, 52–119 (2013).

Janvier, P. Early Vertebrates (Clarendon,1996).

Darwin, C. On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life 1st edn (Murray, 1859).

Benoit, J., Abdala, F., Manger, P. R. & Rubidge, B. S. The sixth sense in mammalian forerunners: variability of the parietal foramen and the evolution of the pineal eye in South African Permo-Triassic Eutheriodont Therapsids. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 61, 777–789 (2016).

Lamb, T. D., Collin, S. P. & Pugh, E. N. Evolution of the vertebrate eye: opsins, photoreceptors, retina and eye cup. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8, 960–976 (2007).

Clements, T. et al. The eyes of Tullimonstrum reveal a vertebrate affinity. Nature 532, 500–503 (2016).

Gabbott, S. E. et al. Pigmented anatomy in Carboniferous cyclostomes and the evolution of the vertebrate eye. Proc. Biol. Sci. 283, 20161151 (2016).

Conway Morris, S. & Caron, J.-B. A primitive fish from the Cambrian of North America. Nature 512, 419–422 (2014).

Gabbott, S. E., Sansom, R. S. & Purnell, M. A. Systematic analysis of exceptionally preserved fossils: correlated patterns of decay and preservation. Palaeontology 64, 789–803 (2021).

Braun, K. & Stach, T. Structure and ultrastructure of eyes and brains of Thalia democratica (Thaliacea, Tunicata, Chordata). J. Morphol. 278, 1421–1437 (2017).

Shu, D.-G. et al. Lower Cambrian vertebrates from south China. Nature 402, 42–46 (1999).

Shu, D.-G. et al. Head and backbone of the Early Cambrian vertebrate Haikouichthys. Nature 421, 526–529 (2003).

Hou, X.-G., Aldridge, R. J., Siveter, D. J., Siveter, D. J. & Feng, X.-H. New evidence on the anatomy and phylogeny of the earliest vertebrates. Proc. Biol. Sci. 269, 1865–1869 (2002).

Zhao, J., Li, G.-B. & Selden, P. A. A poorly preserved fish-like animal from the Chengjiang Lagerstätte (Cambrian series 2, stage 3). Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 520, 163–172 (2019).

Zhang, X.-G. & Hou, X.-G. Evidence for a single median fin-fold and tail in the Lower Cambrian vertebrate Haikouichthys ercaicunensis. J. Evol. Biol. 17, 1162–1166 (2004).

Liu, Y. et al. Comparisons of the structural and chemical properties of melanosomes isolated from retinal pigment epithelium, iris and choroid of newborn and mature bovine eyes. Photochem. Photobiol. 81, 510–516 (2005).

Shawkey, M. D., D’Alba, L., Xiao, M., Schutte, M. & Buchholz, R. Ontogeny of an iridescent nanostructure composed of hollow melanosomes. J. Morphol. 276, 378–384 (2015).

D’Alba, L. & Shawkey, M. D. Melanosomes: biogenesis, properties, and evolution of an ancient organelle. Physiol. Rev. 99, 1–19 (2019).

Roy, A., Pittman, M., Kaye, T. G. & Saitta, E. T. Sediment-encased pressure–temperature maturation experiments elucidate the impact of diagenesis on melanin-based fossil color and its paleobiological implications. Paleobiology 49, 712–732 (2023).

Agrup, G., Hansson, C., Rorsman, H. & Rosengren, E. The effect of cysteine on oxidation of tyrosine, dopa, and cysteinyldopas. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 272, 103–115 (1982).

Bush, W. D. et al. The surface oxidation potential of human neuromelanin reveals a spherical architecture with a pheomelanin core and a eumelanin surface. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 14785–14789 (2006).

Simon, J. D. & Peles, D. N. The red and the black. Acc. Chem. Res. 43, 1452–1460 (2010).

Colleary, C. et al. Chemical, experimental, and morphological evidence for diagenetically altered melanin in exceptionally preserved fossils. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 12592–12597 (2015).

Briggs, D. E. G. & Williams, S. H. The restoration of flattened fossils. Lethaia 14, 157–164 (1981).

Dearden, R. P. et al. The three-dimensionally articulated oral apparatus of a Devonian heterostracan sheds light on feeding in Palaeozoic jawless fishes. Proc. Biol. Sci. 291, 20232258 (2024).

Gagnier, P. Sacabambaspis janvieri, vertebre Ordovicien de Bolivie. I. Analyse morphologique. Ann. Paléontol. 79, 19–69 (1993).

Fritzsch, B. & Martin, P. R. Vision and retina evolution: how to develop a retina. IBRO Neurosci. Rep. 12, 240–248 (2022).

Ekström, P. & Meissl, H. Evolution of photosensory pineal organs in new light: the fate of neuroendocrine photoreceptors. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. 358, 1679–1700 (2003).

Janvier, P. & Arsenault, M. The anatomy of Euphanerops longaevus Woodward, 1900, an anaspid-like jawless vertebrate from the Upper Devonian of Miguasha, Quebec, Canada. Geodiversitas 29, 143–216 (2007).

Gai, Z.-K., Donoghue, P. C. J., Zhu, M., Janvier, P. & Stampanoni, M. Fossil jawless fish from China foreshadows early jawed vertebrate anatomy. Nature 476, 324–327 (2011).

Erwin, D. H. et al. The Cambrian conundrum: early divergence and later ecological success in the early history of animals. Science 334, 1091–1097 (2011).

Meert, J. G., Levashova, N. M., Bazhenov, M. L. & Landing, E. Rapid changes of magnetic field polarity in the late Ediacaran: linking the Cambrian evolutionary radiation and increased UV-B radiation. Gondwana Res. 34, 149–157 (2016).

Nilsson, D.-E. Eye evolution and its functional basis. Vis. Neurosci. 30, 5–20 (2013).

Vinther, J., Porras, L., Young, F. J., Budd, G. E. & Edgecombe, G. D. The mouth apparatus of the Cambrian gilled lobopodian Pambdelurion whittingtoni. Palaeontology 59, 841–849 (2016).

Park, T.-Y. S. et al. A giant stem-group chaetognath. Sci. Adv. 10, eadi6678 (2024).

Vinther, J. et al. A fossilised ventral ganglion reveals a chaetognath affinity for Cambrian nectocaridids. Sci. Adv. 11, eadu6990 (2025).

Paterson, J. R. et al. Acute vision in the giant Cambrian predator Anomalocaris and the origin of compound eyes. Nature 480, 237–240 (2011).

Kasumyan, A. O. & Pavlov, D. S. Evolution of schooling behavior in fish. J. Ichthyol. 58, 670–678 (2018).

Bok, M. J. & Buschbeck, E. K. in Distributed Vision: From Simple Sensors to Sophisticated Combination Eyes (eds Buschbeck, E. K. & Bok, M. J.) 1–19 (Springer, 2023).

Liu, C.-X. The Dark Forest (Chongqing Press, 2008).

Rincón Camacho, L. et al. The pineal complex: a morphological and immunohistochemical comparison between a tropical (Paracheirodon axelrodi) and a subtropical (Aphyocharax anisitsi) characid species. J. Morphol. 277, 1355–1367 (2016).

Dearden, R. P. et al. The oldest three-dimensionally preserved vertebrate neurocranium. Nature 621, 782–787 (2023).

Lindgren, J. et al. Skin pigmentation provides evidence of convergent melanism in extinct marine reptiles. Nature 506, 484–488 (2014).

Lindgren, J. et al. Molecular preservation of the pigment melanin in fossil melanosomes. Nat. Commun. 3, 824 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We thank the students from the research group on problematic fossils and the early animal radiation event at Yunnan University for their assistance with fieldwork. We are grateful to M. Brazaeu for discussions on the presence of pineal eyes in early vertebrates; T. Zhao for comments on an early version of the paper; J.-B. Caron for providing images of M. walcotti; and T. Clements for providing images of Elonichthys peltigerus, Platysomus circularis and Bandringa rayi. We also thank J. Xie, D. Gao and J. Yang (Electron Microscopy Center of Yunnan University) for assistance with FIB and TEM analyses, as well as L. Sun (Electron Microscopy Center at Shanghai Jiaotong University) for ToF-SIMS analysis. This study was funded by the Yunnan Science & Technology Champion Project (202305AB350006) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42072019). P.C. acknowledges support from the Yunling Scholarship of the Yunnan Revitalization Talent Support Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.C., S.G. and J.V. conceived the project. P.C., X.L., S.Z. and F.W. collected the specimens. X.L. and S.Z. collected and analysed the data and, together with the other authors, wrote the first draft of the paper. X.L. and S.Z. made the figures. P.C. and X.X. secured funding. P.C., J.V., S.G. and X.X. supervised the project and edited the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Per Ahlberg and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

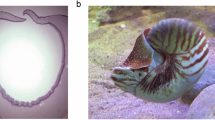

Extended Data Fig. 1 Preservation of eyes and lens in selected fossil vertebrates.

a-b, Haikouichthys ercaicunensis (YNGIP-90285) showing lateral eyes (grey) and pineal eyes (green) with lens (blue). c, carbon element map of H. ercaicunensis (YNGIP-90285) head. d, H. ercaicunensis (YNGIP-90284), white arrows showing lens. e, H. ercaicunensis (YNGIP-90296). f, carbon element map of H. ercaicunensis (YNGIP-90296), yellow arrows indicating left pineal eye. g, (YNGIP-90283), eyes of H. ercaicunensis showing lens (white arrows). h, eyes of H. ercaicunensis showing lens (white arrows) (YNGIP-90289). i, carbon element map of the same region in h, note the absence of carbon in the lens (white arrows). j, m, lens in Elonichthys peltigerus (ROM56794). k, n, lens in Platysomus circularis (PF7333). l, o, lens in Bandringa rayi (ROM56789). (j–o) image courtesy of Thomas Clements. Scale bars, 200 μm (a–f); 50 μm (g–i); 5 mm (j–o). Panels j–o reproduced with permission from ref. 7, Springer Nature Limited.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Raman spectroscopic data across specimens supporting remains in the Chengjiang myllokunmingids eyes are organic material.

Note the consistency of Raman spectroscopic data across specimens, which are distinct from the negative control of the Chengjiang sediment. D and G, feature bands of organic materials.

Extended Data Fig. 3

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis of carbonaceous remains in the eyes of the Chengjiang myllokunmingids (YNGIP 90291).

Extended Data Fig. 4 The frequency distribution and Gaussian fitting of the length-to-width ratio of the melanosomes in the eyes of the Chengjiang vertebrates.

a, Haikouichthys ercaicunensis (n = 549). b, myllokunmingid sp. (n = 500). n refers to the measured number of melanosome microbodies. xc: peak centre value; R2: regression coefficient.

Extended Data Fig. 5 The frequency distribution and Gaussian fitting of the length-to-width ratio of the melanosomes in the lateral and pineal eyes of Haikouichthys ercaicunensis.

a, pineal eyes (n = 250). b, lateral eyes (n = 549). n refers to the measured number of melanosome microbodies. xc: peak centre value; R2: regression coefficient.

Extended Data Fig. 6 SEM, FIB and TEM images of the melanosome in the eyes of Haikouichthys ercaicunensis.

a-b, Backscattered electron image (SEM) of H. ercaicunensis head. c-d, Secondary electron image (SEM) of the melanosome in the eyes (arrowed in a) of H. ercaicunensis. e, f, FIB slicing of the eye (arrowed in a) of H. ercaicunensis. g, i, TEM images of single melanosomes microbody, with enlarged details in i (boxed in g). h, Carbon (C, red), silicon (Si, blue), and iron (Fe, green) elemental map of a single melanosome as shown in g. Scale bars, 500 μm (a); 20 μm (b); 2 μm (c-f); 100 nm (g, h); 20 nm (i).

Extended Data Fig. 7 Detailed PCA result of negative ToF–SIMS spectra.

a, the PCA result of 54 negative secondary ion peaks obtained from the following samples: fresh melanin, artificially matured melanin (aged for 24 h at 200 °C/250 bar and 250 °C/250 bar), fossil melanin, various melanin-negative controls, and specimens of Chengjiang myllokunmingids. b, Comparison of ToF-SIMS full spectra between Haikouichthys eyes (top) with a negative control of the host sediment (bottom) from the Chengjiang biota. c, loadings for principal component analysis (panel a and Fig. 2a), showing the contribution of specific ion fragments to the positioning of specimens along the x-axis (PC1) and y-axis (PC2), respectively. d, the list of details of the numbered samples in a.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Swarming behaviour of myllokunmingid sp.

a, YNGIP-90293, b, YNGIP-90292, with individuals occurring in dense aggregations. Scale bar, 2 cm (a), 1 cm (b).

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Lei, X., Zhang, S., Cong, P. et al. Four camera-type eyes in the earliest vertebrates from the Cambrian Period. Nature 650, 150–155 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09966-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09966-0