Abstract

The directed evolution of biomolecules is an iterative process. Although advancements in language models have expedited protein evolution, effectively evolving RNA remains a challenge. RNA aptamers, selected for their binding properties, provide an ideal system to address this challenge, yet traditional aptamer discovery still relies on labor-intensive, multi-round screening. Here we introduce GRAPE-LM (generator of RNA aptamers powered by activity-guided evolution and language model), a generative artificial intelligence framework designed for the one-round evolution of RNA aptamers. GRAPE-LM integrates a transformer-based conditional autoencoder with nucleic acid language models and is guided by CRISPR−Cas-based aptamer screening data derived from intracellular environments. We validate GRAPE-LM on three disparate targets: the human T cell receptor CD3ε, the receptor-binding domain of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and the human oncogenic transcription factor c-Myc (an intracellular disordered protein). GRAPE-LM, informed with only a single round of CRISPR−Cas-based screening, successfully obtains RNA aptamers that outperform those driven from multiple rounds of human selection and optimization.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The CRISmers sequencing data from both primary screen and pooled examination are available from Zenodo: https://zenodo.org/records/18050896 (ref. 11) and https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.18005327 (ref. 79). The minimum datasets used and model checkpoints for GRAPE-LM are available from GitHub: https://github.com/tansaox2008123/GRAPE-LM. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The source code of GRAPE-LM is available at https://github.com/tansaox2008123/GRAPE-LM. Through the GRAPE-LM online platform (https://grape-lm.bioailab.net/), researchers can easily retrieve aptamer sequences designed for three specific molecular targets featured in this publication.

References

Zhou, J. & Rossi, J. Aptamers as targeted therapeutics: current potential and challenges. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 16, 181–202 (2017).

Zhang, J., Lang, M., Zhou, Y. & Zhang, Y. Predicting RNA structures and functions by artificial intelligence. Trends Genet. 40, 94–107 (2024).

Hayes, T. et al. Simulating 500 million years of evolution with a language model. Science 387, 850–858 (2025).

Zhang, H. et al. Algorithm for optimized mRNA design improves stability and immunogenicity. Nature 621, 396–403 (2023).

Jiang, K. et al. Rapid in silico directed evolution by a protein language model with EVOLVEpro. Science 387, eadr6006 (2025).

Bunka, D. H. J. & Stockley, P. G. Aptamers come of age – at last. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4, 588–596 (2006).

Zhang, Y., Juhas, M. & Kwok, C. K. Aptamers targeting SARS-COV-2: a promising tool to fight against COVID-19. Trends Biotechnol. 41, 528–544 (2023).

Zhang, Y., Lai, B. S. & Juhas, M. Recent advances in aptamer discovery and applications. Molecules 24, 941 (2019).

Vargas-Montes, M. et al. Enzyme-linked aptamer assay (ELAA) for detection of toxoplasma ROP18 protein in human serum. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 9, 386 (2019).

Tuerk, C. & Gold, L. Systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment: RNA ligands to bacteriophage T4 DNA polymerase. Science 249, 505–510 (1990).

Zhang, J. et al. Repurposing CRISPR/Cas to discover SARS-CoV-2 detecting and neutralizing aptamers. Adv. Sci. 10, 2300656 (2023).

Su-Tobon, Q. et al. CRISPR-Hybrid: a CRISPR-mediated intracellular directed evolution platform for RNA aptamers. Nat. Commun. 16, 595 (2025).

Iwano, N., Adachi, T., Aoki, K., Nakamura, Y. & Hamada, M. Generative aptamer discovery using RaptGen. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2, 378–386 (2022).

Wang, Z. et al. AptaDiff: de novo design and optimization of aptamers based on diffusion models. Brief. Bioinform. 25, bbae517 (2024).

Wong, F. et al. Deep generative design of RNA aptamers using structural predictions. Nat. Comput. Sci. 4, 829–839 (2024).

Zhou, X. et al. ProRefiner: an entropy-based refining strategy for inverse protein folding with global graph attention. Nat. Commun. 14, 7434 (2023).

Dauparas, J. et al. Robust deep learning–based protein sequence design using ProteinMPNN. Science 378, 49–56 (2022).

Ren, M., Yu, C., Bu, D. & Zhang, H. Accurate and robust protein sequence design with CarbonDesign. Nat. Mach. Intell. 6, 536–547 (2024).

Lee, G., Jang, G. H., Kang, H. Y. & Song, G. Predicting aptamer sequences that interact with target proteins using an aptamer-protein interaction classifier and a Monte Carlo tree search approach. PLoS ONE 16, e0253760 (2021).

Shin, I. et al. AptaTrans: a deep neural network for predicting aptamer-protein interaction using pretrained encoders. BMC Bioinformatics 24, 447 (2023).

Patel, S. et al. AptaBLE: an enhanced deep learning platform for aptamer protein interaction prediction and design. In Machine Learning for Structural Biology Workshop, NeurIPS 2024 https://www.mlsb.io/papers_2024/AptaBLE:_An_Enhanced_Deep_Learning_Platform_for_Aptamer_Protein_Interaction_Prediction_and_Design.pdf (2024).

Alipanahi, B., Delong, A., Weirauch, M. T. & Frey, B. J. Predicting the sequence specificities of DNA- and RNA-binding proteins by deep learning. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 831–838 (2015).

Nithin, C., Kmiecik, S., Błaszczyk, R., Nowicka, J. & Tuszyńska, I. Comparative analysis of RNA 3D structure prediction methods: towards enhanced modeling of RNA–ligand interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, 7465–7486 (2024).

Chen, L. T. et al. Target sequence-conditioned design of peptide binders using masked language modeling. Nat. Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-025-02761-2 (2025).

Torres, M. D. T., Chen, L. T., Wan, F., Chatterjee, P. & de la Fuente-Nunez, C. Generative latent diffusion language modeling yields anti-infective synthetic peptides. Cell Biomat. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celbio.2025.100183 (2025).

Shen, T. et al. Accurate RNA 3D structure prediction using a language model-based deep learning approach. Nat. Methods 21, 2287–2298 (2024).

Akiyama, M. & Sakakibara, Y. Informative RNA base embedding for RNA structural alignment and clustering by deep representation learning. NAR Genom. Bioinform. 4, lqac012 (2022).

Wang, N. et al. Multi-purpose RNA language modelling with motif-aware pretraining and type-guided fine-tuning. Nat. Mach. Intell. 6, 548–557 (2024).

Patel, S., Peng, F. Z., Fraser, K., Chatterjee, P. & Yao, S. EvoFlow-RNA: generating and representing non-coding RNA with a language model. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.02.25.639942 (2025).

Penić, R. J., Vlašić, T., Huber, R. G., Wan, Y. & Šikić, M. RiNALMo: general-purpose RNA language models can generalize well on structure prediction tasks. Nat. Commun. 16, 5671 (2025).

Nguyen, E. et al. Sequence modeling and design from molecular to genome scale with Evo. Science 386, eado9336 (2024).

Ishida, R. et al. RaptRanker: in silico RNA aptamer selection from HT-SELEX experiment based on local sequence and structure information. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, e82 (2020).

Li, W. & Godzik, A. Cd-hit: a fast program for clustering and comparing large sets of protein or nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 22, 1658–1659 (2006).

Freage, L., Jamal, D., Williams, N. B. & Mallikaratchy, P. R. A homodimeric aptamer variant generated from ligand-guided selection activates the T cell receptor cluster of differentiation 3 complex. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 22, 167–178 (2020).

Zumrut, H. et al. Ligand-guided selection with artificially expanded genetic information systems against TCR-CD3ε. Biochemistry 59, 552–562 (2020).

Zumrut, H. E. et al. Integrating ligand-receptor interactions and in vitro evolution for streamlined discovery of artificial nucleic acid ligands. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 17, 150–163 (2019).

Raddatz, M.-S. L. et al. Enrichment of cell-targeting and population-specific aptamers by fluorescence-activated cell sorting. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 47, 5190–5193 (2008).

Nakhjavani, M. et al. A flow cytometry-based cell surface protein binding assay for assessing selectivity and specificity of an anticancer aptamer. J. Vis. Exp. 187, e64304 (2022).

Abramson, J. et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 630, 493–500 (2024).

Li, J., Zhang, S., Zhang, D. & Chen, S.-J. Vfold-Pipeline: a web server for RNA 3D structure prediction from sequences. Bioinformatics 38, 4042–4043 (2022).

Kretsch, R. C. et al. Functional relevance of CASP16 nucleic acid predictions as evaluated by structure providers. Proteins 94, 51–78 (2026).

Shannon, C. E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 27, 379–423 (1948).

Yan, Y., Tao, H., He, J. & Huang, S.-Y. The HDOCK server for integrated protein–protein docking. Nat. Protocols 15, 1829–1852 (2020).

Valero, J. et al. A serum-stable RNA aptamer specific for SARS-CoV-2 neutralizes viral entry. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2112942118 (2021).

Sun, M. et al. Aptamer blocking strategy inhibits SARS-CoV-2 virus infection. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 60, 10266–10272 (2021).

Bartoschik, T. et al. Near-native, site-specific and purification-free protein labeling for quantitative protein interaction analysis by MicroScale Thermophoresis. Sci. Rep. 8, 4977 (2018).

Song, Y. et al. Discovery of aptamers targeting the receptor-binding domain of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Anal. Chem. 92, 9895–9900 (2020).

Li, J. et al. Diverse high-affinity DNA aptamers for wild-type and B.1.1.7 SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins from a pre-structured DNA library. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, 7267–7279 (2021).

Liu, X. et al. Neutralizing aptamers block S/RBD−ACE2 interactions and prevent host cell infection. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 60, 10273–10278 (2021).

Yang, G. et al. Identification of SARS-CoV-2-against aptamer with high neutralization activity by blocking the RBD domain of spike protein 1. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 6, 227 (2021).

Alves Ferreira-Bravo, I. & DeStefano, J. J. Xeno-nucleic acid (XNA) 2′-fluoro-arabino nucleic acid (FANA) aptamers to the receptor-binding domain of SARS-CoV-2 S protein block ACE2 binding. Viruses 13, 1983 (2021).

Saify Nabiabad, H., Amini, M. & Demirdas, S. Specific delivering of RNAi using spike’s aptamer-functionalized lipid nanoparticles for targeting SARS-CoV-2: a strong anti-Covid drug in a clinical case study. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 99, 233–246 (2022).

Lorenz, R. et al. ViennaRNA Package 2.0. Algorithms Mol. Biol. 6, 26 (2011).

Guo, C. et al. Transversions have larger regulatory effects than transitions. BMC Genomics 18, 394 (2017).

Sun, M. et al. Spherical neutralizing aptamer inhibits SARS-CoV-2 infection and suppresses mutational escape. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 21541–21548 (2021).

Dang, C. V., Reddy, E. P., Shokat, K. M. & Soucek, L. Drugging the ‘undruggable’ cancer targets. Nat. Rev. Cancer 17, 502–508 (2017).

Wang, Y. et al. Antitumor effect of anti-c-Myc aptamer-based PROTAC for degradation of the c-Myc protein. Adv. Sci. 11, 2309639 (2024).

He, J., Spokoyny, D., Neubig, G. & Berg-Kirkpatrick, T. Lagging inference networks and posterior collapse in variational autoencoders. In The Seventh International Conference on Learning Representations https://openreview.net/pdf/47f79f4015dbabc7f2eab6e432cddf975cf1c486.pdf (ICLR, 2019).

Dieng, A. B., Kim, Y., Rush, A. M. & Blei, D. M. Avoiding latent variable collapse with generative skip models. In Proc. Twenty-Second International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics (eds Kamalika, C. & Masashi, S.) 2397–2405 (PMLR, 2019).

Hawkins-Hooker, A. et al. Generating functional protein variants with variational autoencoders. PLoS Comput. Biol. 17, e1008736 (2021).

Zhang, C., Shine, M., Pyle, A. M. & Zhang, Y. US-align: universal structure alignments of proteins, nucleic acids, and macromolecular complexes. Nat. Methods 19, 1109–1115 (2022).

Madeira, F. et al. The EMBL-EBI Job Dispatcher sequence analysis tools framework in 2024. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, W521–W525 (2024).

Crooks, G. E., Hon, G., Chandonia, J. M. & Brenner, S. E. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 14, 1188–1190 (2004).

Ferruz, N., Schmidt, S. & Höcker, B. ProtGPT2 is a deep unsupervised language model for protein design. Nat. Commun. 13, 4348 (2022).

Ni, B., Kaplan, D. L. & Buehler, M. J. ForceGen: end-to-end de novo protein generation based on nonlinear mechanical unfolding responses using a language diffusion model. Sci. Adv. 10, eadl4000 (2024).

Madani, A. et al. Large language models generate functional protein sequences across diverse families. Nat. Biotechnol. 41, 1099–1106 (2023).

Zhang, Q. et al. Integrating protein language models and automatic biofoundry for enhanced protein evolution. Nat. Commun. 16, 1553 (2025).

Singh, A. Protein language models guide directed antibody evolution. Nat. Methods 20, 785 (2023).

Dalla-Torre, H. et al. Nucleotide Transformer: building and evaluating robust foundation models for human genomics. Nat. Methods 22, 287–297 (2025).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. In Proc. 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 6000–6010 (Curran Associates, 2017).

Castro, E. et al. Transformer-based protein generation with regularized latent space optimization. Nat. Mach. Intell. 4, 840–851 (2022).

Ferruz, N. & Höcker, B. Controllable protein design with language models. Nat. Mach. Intell. 4, 521–532 (2022).

Nguyen Quang, N., Bouvier, C., Henriques, A., Lelandais, B. & Ducongé, F. Time-lapse imaging of molecular evolution by high-throughput sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 7480–7494 (2018).

Chan, C. Y. et al. A structural interpretation of the effect of GC-content on efficiency of RNA interference. BMC Bioinformatics 10, S33 (2009).

Mathews, D. H., Sabina, J., Zuker, M. & Turner, D. H. Expanded sequence dependence of thermodynamic parameters improves prediction of RNA secondary structure. J. Mol. Biol. 288, 911–940 (1999).

Molejon, N. A. et al. Selection of G-rich ssDNA aptamers for the detection of enterotoxins of the cholera toxin family. Anal. Biochem. 669, 115118 (2023).

Melikishvili, M. et al. SELEX identifies high-affinity RNA targets for chromatin-binding proteins PARP1 and MeCP2. iScience 28, 113299 (2025).

Thiel, W. H. et al. Nucleotide bias observed with a short SELEX RNA aptamer library. Nucleic Acid Ther. 21, 253–263 (2011).

Zhang, J. et al. CRISmers NGS data used and generated by GRAPE-LM (1.0). Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.18005327 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank all colleagues in our laboratories for experimental assistance and helpful discussions. This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (no. 2023YFA0915000 to Y.W.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 91957121 and no. 82273967 to Y.W., no. 82273890 to Y.Z. and no. 62302311 to Jun Zhang), the Department of Science and Technology of Guangdong Province (no. 2021QN020576 to Y.W.), the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (no. 2024A1515011681 to Jun Zhang), the Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (no. ZDSYS20220303153551001 to Y.W.), the Shenzhen Stable Support Grant (no. GXWD 20231130103401001 to Y.Z.), the Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (no. JCYJ20240813104817024 to Y.Z.), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (no. 2023M742397 and no. 2024T170585 to Ju Zhang), the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (no. GZC20231724 to Ju Zhang) and the Internal Fund of the National Engineering Laboratory for Big Data System Computing Technology (no. SZU-BDSC-IF2024-01 to Jun Zhang).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.W., Y.Z. and Jun Zhang conceived and designed the study. Jun Zhang, S.T., H.Z. and X.M. performed modeling and computational analyses. Ju Zhang, C.L., Y.C. and B.L. performed wet lab experiments. All authors analyzed the data and interpreted the results. Y.W., Y.Z., Jun Zhang and Ju Zhang wrote the manuscript, with contributions from all coauthors. Jun Zhang and Ju Zhang contributed equally to this work. Y.W. and Y.Z. supervised the project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Biotechnology thanks Pranam Chatterjee and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

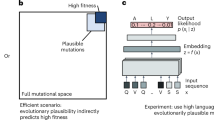

Extended Data Fig. 1 Comparison of two latent spaces and data processing.

(a) Comparison of activity-guided versus sequence similarity-based semantic spaces. The activity-guided latent space (constrained by pseudo-activity scores) enables focused sampling of functional aptamers, while traditional sequence similarity-based spaces permit only random exploration. (b) Data processing pipeline. Training and test datasets were derived from the first-round output of CRISmers (an intracellular CRISPR/Cas-based aptamer screening system). Unique sequences were assigned pseudo-activity scores (0-1 scale) based on enrichment frequencies. \(\lambda\) is a hyperparameter that needs to be optimized for different targets, and it is recommended to initially use 0.05. The sequences were clustered using CD-HIT with a threshold of 0.8. Sequences only with a high confidence were used (clusters with more than 10 reads or individual unique sequences with more than 5 reads). For targets (such as RBD) with fewer initial sequences, the threshold of individual unique sequences was set to 1. The final selected sequences were then randomly divided into training and test groups in an 8:2 ratio to construct the training and test sets. Icons in figures were created with BioRender (https://www.biorender.com/).

Extended Data Fig. 2 Exploring the role of activity guidance strategy.

To evaluate the regulatory role of the activity-guidance module on latent space organization, we analyzed how varying the activity-guidance loss weight influenced the separation between high-ranking and low-ranking activity samples. Using t-SNE, we mapped the latent features generated by GRAPE-LM’s encoder of 2,000 samples per group from high-dimensional to 2D space, facilitating cluster analysis of generated aptamers based on functional similarity.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Comparative results of GRAPE-LM and RaptGen in terms of the recovery rate.

The overall recovery rates are calculated using the corresponding model on the test sets of four targets from CRISmers (a) and SELEX (b). Data plot mean with standard deviation (SD), n = 3 experimental replicates. The statistical analyses were conducted using a two-sided Student’s t-test (**** P < 0.0001).

Extended Data Fig. 4 Dose-dependent flow cytometry analyses of the Cy5-labeled CD3ε aptamers.

(a) Representative flow cytometry histograms showing fluorescence intensity shifts in CD3ε-Ko #2 cell after treatment with serially diluted Cy5-aptamers. (b) Dose-response binding curves of the Cy5-labeled CD3ε aptamers on Jurkat cells. CD3ε knock-out cells (Jurkat CD3ε-Ko #1 and #2) serve as negative control to assess binding specificity. Apparent equilibrium dissociation constants (Kd) were derived from nonlinear regression analysis (one-site specific binding model) using GraphPad Prism. Data represent mean ± SD (n = 3 biological replicates).

Extended Data Fig. 5 Characterization of aptamer binding affinity for CD3ε.

(a) Luciferase reporter assay results of the top 50 candidate sequences from one round of CRISmers screening, ranked by sequencing read abundance. Data represent mean with SD, n = 3 biological replicates. (b) Comparative GFP reporter assay of libraries from one-round screening using CRISmers versus GRAPE-LM. “Mock” denotes transfection with unrelated control plasmids; “CRISmers” represents transfection with the sub-library constructed after one round of CRISmers screening; “GRAPE-LM” corresponds to transfection with the library generated by GRAPE-LM in a single round.

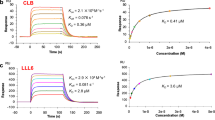

Extended Data Fig. 6 The Microscale Thermophoresis examination and the additional results for RBD.

(a) The schematic diagram of the Microscale Thermophoresis (MST). Icons in figures were created with BioRender (https://www.biorender.com/). (b) MST binding curves of previously reported SELEX-derived aptamers targeting the RBD of SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein. Data showed mean with SD, with n = 3 biological replicates. (c) Results of Kd value determination based on MST for the Lead of 2nd round and the Lead of 5th round from iterative CRISmers. Data showed mean with SD, with n = 3 biological replicates. The receptor-binding domain (RBD) resides in the S1 subunit of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike glycoprotein. To validate binding specificity during MST assays, the S2 subunit—a non-target structural region—was used as a negative control, ensuring the aptamer selectively recognizes the RBD rather than unrelated epitopes.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Case study of the internal loop motif in two representative aptamers.

Prediction of secondary structures and functional analysis of predicted binding sites for representative CD3ε (a) and RBD (b) aptamers. The dashed box highlights the computationally predicted binding site within the internal loop. Data represent the mean with SD (n = 3 biological replicates).

Extended Data Fig. 8 A powerful new paradigm of accelerated RNA aptamer evolution.

This new paradigm is enabled by one shot GRAPE-LM introduced in this work, informed by one round CRISmers. Icons in figures were created with BioRender (https://www.biorender.com/).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1−12, Supplementary Tables 1−4 and Supplementary Notes 1−3.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 7

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, J., Zhang, J., Tang, S. et al. Single-round evolution of RNA aptamers with GRAPE-LM. Nat Biotechnol (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-026-03007-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-026-03007-5