Abstract

Mobile genetic elements (MEs) are heritable mutagens that recursively generate structural variants (SVs). ME variants (MEVs) are difficult to genotype and integrate in statistical genetics, obscuring their impact on genome diversification and traits. We developed a tool that accurately genotypes MEVs using short-read whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and applied it to global human populations. We find unexpected population-specific MEV differences, including an Alu insertion distribution distinguishing Japanese from other populations. Integrating MEVs with expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) maps shows that MEV classes regulate tissue-specific gene expression by shared mechanisms, including creating or attenuating enhancers and recruiting post-transcriptional regulators, supporting class-wide interpretability. MEVs more often associate with gene expression changes than SNVs, thus plausibly impacting traits. Performing genome-wide association study (GWAS) with MEVs pinpoints potential causes of disease risk, including a LINE-1 insertion associated with keloid and fasciitis. This work implicates MEVs as drivers of human divergence and disease risk.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

MEVs identified from 1000GP and summary statistics of eQTL analysis were uploaded in Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7703708). The positions of and allele frequencies of MEVs identified from Japanese recruited by BBJ are available from National Bioscience Database Center (https://humandbs.biosciencedbc.jp/en/, accession ID: hum0014.v28) without any access restrictions. Summary statistics of GWAS are publicly available from our website (JENGER, http://jenger.riken.jp/en). Human reference genomes, human_g1k_v37, hs37d5, and GRCh38DH, are available from 1000GP repository (http://ftp.1000genomes.ebi.ac.uk/vol1/ftp/technical/reference/human_g1k_v37.fasta.gz, ftp://ftp.1000genomes.ebi.ac.uk/vol1/ftp/technical/reference/phase2_reference_assembly_sequence/hs37d5.fa.gz, and http://ftp.1000genomes.ebi.ac.uk/vol1/ftp/technical/reference/GRCh38_reference_genome/GRCh38_full_analysis_set_plus_decoy_hla.fa, respectively). The 30× WGS data from 3,202 individuals recruited by 1000GP were downloaded from the 1000GP website (http://ftp.1000genomes.ebi.ac.uk/vol1/ftp/data_collections/1000G_2504_high_coverage/). SV callset generated by the phased assembly variant caller (PAV) in part of 1000GP is available from 1000GP repository (http://ftp.1000genomes.ebi.ac.uk/vol1/ftp/data_collections/HGSVC2/release/v2.0/integrated_callset/variants_freeze4_sv_insdel.tsv.gz). SV callset generated by Panenie in part of 1000GP is available from 1000GP repository (http://ftp.1000genomes.ebi.ac.uk/vol1/ftp/data_collections/HGSVC2/release/v1.0/PanGenie_results). GATK-SV callset generated by Panenie in part of 1000GP is available from 1000GP repository (http://ftp.1000genomes.ebi.ac.uk/vol1/ftp/data_collections/1000G_2504_high_coverage/working/20210124.SV_Illumina_Integration/1KGP_3202.Illumina_ensemble_callset.freeze_V1.vcf.gz). Human repeat library is available from RepBase (https://www.girinst.org/repbase). Gene models, GenCode GTF v26 and v26lift37, are available from GenCode (https://www.gencodegenes.org/human). SNVs found from participants in 1000GP are available from 1000GP repository (http://ftp.1000genomes.ebi.ac.uk/vol1/ftp/release/20130502). ENCODE cCRE dataset is available from ENCODE repository (https://screen.encodeproject.org). Accession numbers of histone ChIP-seq data from ENCODE are summarized in Supplementary Table 7. Other datasets of ESCs we used are available from ENCODE repository (https://screen.encodeproject.org) and deposited under accession numbers ENCFF601NBW (CpG methylation), ENCFF524BMX (CpG methylation), ENCFF379ZXG (CHG methylation), ENCFF086MMC (CHG methylation), ENCFF417VRB (CHH methylation), ENCFF918PML (CHH methylation), ENCFF000KUF (Repli-Chip), ENCFF000KUG (Repli-Chip), ENCFF000KUK (Repli-Chip), ENCFF905XDS (DNase-seq), ENCFF574LKL (DNase-seq), ENCFF338KTY (DNase-seq), ENCFF821AQO (CTCF ChIP-seq), ENCFF418QVJ (phospho-Pol-II A ChIP-seq), ENCFF422HDN (Pol-ll ChIP-seq), and ENCFF834UVX (EP300 ChIP-seq). Annotations of DHS were obtained from data deposited under accession number ENCFF503GCK. Methylation data of iPSCs and ECSs taken by genome tiling array deposited under number accession GSE60821 was used. Hi-C data of H1-hESCs deposited under accession numbers GSM5057489 and GSM5057481 was used. Gene expression profiles during spermatogenesis and early embryo deposited under accession numbers GSE120508 and GSE36552 were used. Read count tables of RNA-sequencing done by GTEx are available from GTEx repository (https://storage.googleapis.com/gtex_analysis_v8/rna_seq_data/GTEx_Analysis_2017-06-05_v8_RNASeQCv1.1.9_exon_reads.parquet and GTEx_Analysis_2017-06-05_v8_RNASeQCv1.1.9_gene_reads.gct.gz). Covariates for eQTL analysis and phased SNVs and indels in GTEx (that is PEER factors, genetic PCs, library preparation methods, sequencing platforms, and sex) are available from NCBI under dbGaP accession number phs000424. The script used to collapse GenCode GTF file is available from the URL below: https://github.com/broadinstitute/gtex-pipeline/blob/master/gene_model/collapse_annotation.py. The script used to apply TMM normalization is available from the URL below: https://github.com/broadinstitute/gtex-pipeline/blob/master/qtl/src/eqtl_prepare_expression.py. MEVs identified in Cao et al. are available from the following URLs: https://genomebiology.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13059-020-02101-4. Gene sets used for gene-set enrichment analysis is available from msigdb (https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb/). 7221 summary statistics of GWAS done by Pan-UKB were downloaded from the URLs listed in a file: https://pan-ukb-us-east-1.s3.amazonaws.com/sumstats_release/phenotype_manifest.tsv.bgz. The ‘tophit’ variants in BBJ were downloaded from http://jenger.riken.jp:8080/top_hits and https://pheweb.jp.

Code availability

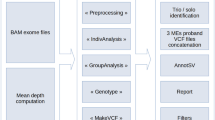

MEGAnE is deposited in Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7703696) and available from GitHub and Dockerhub (https://github.com/shohei-kojima/MEGAnE, https://hub.docker.com/repository/docker/shoheikojima/megane). A complete environment including MEGAnE and other required software is available from Dockerhub.

References

Wells, J. N. & Feschotte, C. A field guide to eukaryotic transposable elements. Annu. Rev. Genet. 54, 539–561 (2020).

Serrato-Capuchina, A. & Matute, D. R. The role of transposable elements in speciation. Genes (Basel) 9, 254 (2018).

Payer, L. M. & Burns, K. H. Transposable elements in human genetic disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 20, 760–772 (2019).

Kobayashi, K. et al. An ancient retrotransposal insertion causes Fukuyama-type congenital muscular dystrophy. Nature 394, 388–392 (1998).

Hancks, D. C. & Kazazian, H. H. J. Roles for retrotransposon insertions in human disease. Mob. DNA 7, 9 (2016).

Kagawa, T. et al. Recessive inheritance of population-specific intronic LINE-1 insertion causes a rotor syndrome phenotype. Hum. Mutat. 36, 327–332 (2015).

Goubert, C., Zevallos, N. A. & Feschotte, C. Contribution of unfixed transposable element insertions to human regulatory variation. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 375, 20190331 (2020).

Chiang, C. et al. The impact of structural variation on human gene expression. Nat. Genet. 49, 692–699 (2017).

Payer, L. M. et al. Alu insertion variants alter gene transcript levels. Genome Res. 31, 2236–2248 (2021).

Cao, X. et al. Polymorphic mobile element insertions contribute to gene expression and alternative splicing in human tissues. Genome Biol. 21, 185 (2020).

Sekar, A. et al. Schizophrenia risk from complex variation of complement component 4. Nature 530, 177–183 (2016).

Payer, L. M. et al. Structural variants caused by Alu insertions are associated with risks for many human diseases. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, E3984–E3992 (2017).

Jacques, P.-É., Jeyakani, J. & Bourque, G. The majority of primate-specific regulatory sequences are derived from transposable elements. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003504 (2013).

Meuleman, W. et al. Index and biological spectrum of human DNase I hypersensitive sites. Nature 584, 244–251 (2020).

Trizzino, M. et al. Transposable elements are the primary source of novelty in primate gene regulation. Genome Res. 27, 1623–1633 (2017).

Sudmant, P. H. et al. An integrated map of structural variation in 2,504 human genomes. Nature 526, 75–81 (2015).

Peter, E. et al. Haplotype-resolved diverse human genomes and integrated analysis of structural variation. Science 372, eabf7117 (2021).

Scott, A. J., Chiang, C. & Hall, I. M. Structural variants are a major source of gene expression differences in humans and often affect multiple nearby genes. Genome Res. 31, 2249–2257 (2021).

Ito, J. et al. A hominoid-specific endogenous retrovirus may have rewired the gene regulatory network shared between primordial germ cells and naïve pluripotent cells. PLoS Genet. 18, e1009846 (2022).

Chuong, E. B., Elde, N. C. & Feschotte, C. Regulatory evolution of innate immunity through co-option of endogenous retroviruses. Science 351, 1083–1087 (2016).

Chaisson, M. J. P. et al. Multi-platform discovery of haplotype-resolved structural variation in human genomes. Nat. Commun. 10, 1784 (2019).

Collins, R. L. et al. A structural variation reference for medical and population genetics. Nature 581, 444–451 (2020).

Abel, H. J. et al. Mapping and characterization of structural variation in 17,795 human genomes. Nature 583, 83–89 (2020).

Jabbari, K. & Bernardi, G. CpG doublets, CpG islands and Alu repeats in long human DNA sequences from different isochore families. Gene 224, 123–128 (1998).

Soumillon, M. et al. Cellular source and mechanisms of high transcriptome complexity in the mammalian testis. Cell Rep. 3, 2179–2190 (2013).

van Bree, E. J. et al. A hidden layer of structural variation in transposable elements reveals potential genetic modifiers in human disease-risk loci. Genome Res. 32, 656–670 (2022).

Vialle, R. A., de Paiva Lopes, K., Bennett, D. A., Crary, J. F. & Raj, T. Integrating whole-genome sequencing with multi-omic data reveals the impact of structural variants on gene regulation in the human brain. Nat. Neurosci. 25, 504–514 (2022).

Lubelsky, Y. & Ulitsky, I. Sequences enriched in Alu repeats drive nuclear localization of long RNAs in human cells. Nature 555, 107–111 (2018).

Fueyo, R., Judd, J., Feschotte, C. & Wysocka, J. Roles of transposable elements in the regulation of mammalian transcription. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 23, 481–497 (2022).

Spracklen, C. N. et al. Identification of type 2 diabetes loci in 433,540 East Asian individuals. Nature 582, 240–245 (2020).

Hautanen, A. Synthesis and regulation of sex hormone-binding globulin in obesity. Int. J. Obes. 24, S64–S70 (2000).

Ogawa, R. et al. Associations between keloid severity and single-nucleotide polymorphisms: importance of rs8032158 as a biomarker of keloid severity. J. Invest. Dermatol. 134, 2041–2043 (2014).

Fujita, M. et al. NEDD4 is involved in inflammation development during keloid formation. J. Invest. Dermatol. 139, 333–341 (2019).

Gardner, E. J. et al. The Mobile Element Locator Tool (MELT): population-scale mobile element discovery and biology. Genome Res. 27, 1916–1929 (2017).

Costantini, M., Auletta, F. & Bernardi, G. The distributions of ‘new’ and ‘old’ Alu sequences in the human genome: the solution of a ‘mystery’. Mol. Biol. Evol. 29, 421–427 (2012).

Baggen, J. et al. Genome-wide CRISPR screening identifies TMEM106B as a proviral host factor for SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Genet. 53, 435–444 (2021).

Van Deerlin, V. M. et al. Common variants at 7p21 are associated with frontotemporal lobar degeneration with TDP-43 inclusions. Nat. Genet. 42, 234–239 (2010).

Marttala, J., Andrews, J. P., Rosenbloom, J. & Uitto, J. Keloids: Animal models and pathologic equivalents to study tissue fibrosis. Matrix Biol. 51, 47–54 (2016).

Linker, S. B., Marchetto, M. C., Narvaiza, I., Denli, A. M. & Gage, F. H. Examining non-LTR retrotransposons in the context of the evolving primate brain. BMC Biol. 15, 68 (2017).

Yampolsky, L. Y. & Stoltzfus, A. Bias in the introduction of variation as an orienting factor in evolution. Evol. Dev. 3, 73–83 (2001).

Hirata, M. et al. Cross-sectional analysis of BioBank Japan clinical data: a large cohort of 200,000 patients with 47 common diseases. J. Epidemiol. 27, S9–S21 (2017).

Nagai, A. et al. Overview of the BioBank Japan Project: study design and profile. J. Epidemiol. 27, S2–S8 (2017).

Ongen, H., Buil, A., Brown, A. A., Dermitzakis, E. T. & Delaneau, O. Fast and efficient QTL mapper for thousands of molecular phenotypes. Bioinformatics 32, 1479–1485 (2016).

Urbut, S. M., Wang, G., Carbonetto, P. & Stephens, M. Flexible statistical methods for estimating and testing effects in genomic studies with multiple conditions. Nat. Genet. 51, 187–195 (2019).

Ishigaki, K. et al. Large-scale genome-wide association study in a Japanese population identifies novel susceptibility loci across different diseases. Nat. Genet. 52, 669–679 (2020).

Zhou, W. et al. Efficiently controlling for case-control imbalance and sample relatedness in large-scale genetic association studies. Nat. Genet. 50, 1335–1341 (2018).

Lee, C. H., Moioli, E. K. & Mao, J. J. Fibroblastic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells using connective tissue growth factor. Conf. Proc. IEEE Eng. Med Biol. Soc. 2006, 775–778 (2006).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all of the participants in BBJ, as well as the staff of BBJ for their assistance. BBJ is supported by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) (grant JP19km0605001). The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) Project was supported by the Common Fund of the Office of the Director of the National Institutes of Health and by NCI, NHGRI, NHLBI, NIDA, NIMH and NINDS. The GTEx data used for the analyses described in this study were obtained from dbGaP accession number phs000424.v8.p2 We are grateful to all of the families at the participating Simons Simplex Collection (SSC) sites, as well as the principal investigators (A. Beaudet, R. Bernier, J. Constantino, E. Cook, E. Fombonne, D. Geschwind, R. Goin-Kochel, E. Hanson, D. Grice, A. Klin, D. Ledbetter, C. Lord, C. Martin, D. Martin, R. Maxim, J. Miles, O. Ousley, K. Pelphrey, B. Peterson, J. Piggot, C. Saulnier, M. State, W. Stone, J. Sutcliffe, C. Walsh, Z. Warren and E. Wijsman). We appreciate obtaining access to genetic and pedigree data on SFARI Base. We acknowledge the resources of the 1000 Genomes Project and HGDP-CEPH Human Genome Diversity Cell Line Panel. We are grateful to the UK Biobank participants contributing to the results made public via the Pan-UK Biobank Resource and acknowledge the Pan-UKBB team (https://pan.ukbb.broadinstitute.org/team). Super-computing resources were provided by Human Genome Center, the Institute of Medical Science, the University of Tokyo (SHIROKANE), and the Office for Information Systems and Cybersecurity, RIKEN (HOKUSAI General Use project G20021 and Q21537). We acknowledge H. Yoshida and T. Suzuki of RIKEN Center for Integrative Medical Sciences for providing plasmids, X. Chen and G. Bourque of Kyoto University and N. Sasa and Y. Okada of Osaka University for testing prerelease versions of MEGAnE, K. Sato and J. Ito of University of Tokyo for helpful discussion, and M. Yoshioka for outstanding administrative support. S. Kojima, M.N. and A.J.K. acknowledge funding from the Incentive Research Projects of RIKEN, supported in part by Resona Bank. S. Kojima acknowledges a funding from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Early-Career Scientists 22K15385. S. Kojima and S.M.H. acknowledge the RIKEN Special Postdoctoral Researcher Program. K. Ito acknowledges fundings from JSPS KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research(B) 21H02919, AMED (JP22ek0210164, JP21tm0724601, JP20km0405209 and JP20ek0109487) and Research Funding for Longevity Sciences from the NCGG. N.F.P. acknowledges funding from JSPS KAKENHI Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research(S) 20H05682, JSPS KAKENHI Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research(B) 21H02972, RIKEN-McGill International Collaborative grant, Gout and Uric Acid Foundation of Japan, Cluster for Pioneering Research under the Hakubi fellowship program and from the discretionary budget of the Director of the RIKEN Center for Integrative Medical Sciences, K. Yamamoto.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

S. Kojima and N.F.P. designed this study. S. Kojima, A.T., M.H., and N.F.P. developed MEGAnE. S. Kojima, S. Koyama, and N.F.P. analyzed data. N.F.P., K.H., K. Ishigaki, K. Ito, C.T., and Y.K. organized data in BBJ. S. Kojima, Y.S., M.E., M.M., S.T., Y.M., Y. Momozawa, and N.F.P. performed targeted deep sequencing. S.M.H., A.J.K., Y.M., Y. Murakawa, C.T., M.N., and Y.N. managed cell culture. S. Kojima, E.H.P., M.K., A.F.G., and R.K. performed wet experiments. S. Kojima and N.F.P. wrote and all authors checked the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Genetics thanks Clement Goubert and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Note and Supplementary Figures 1–47

Supplementary Table 1

Supplementary Tables 1–18

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Kojima, S., Koyama, S., Ka, M. et al. Mobile element variation contributes to population-specific genome diversification, gene regulation and disease risk. Nat Genet 55, 939–951 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-023-01390-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-023-01390-2

This article is cited by

-

Endogenous retroviruses in aging and cancer: from genomic defense to oncogenic activation

Mobile DNA (2025)

-

Molecular effects of transposable element sequences in mammalian cells

Genome Biology (2025)

-

Impact of a horizontally transferred Helitron family on genome evolution in Xenopus laevis

Mobile DNA (2025)

-

Reactivation of retrotransposable elements is associated with environmental stress and ageing

Nature Reviews Genetics (2025)

-

Transposable elements as instructors of the immune system

Nature Reviews Immunology (2025)