Abstract

The UNC13A gene encodes a presynaptic protein that is crucial for setting the strength and dynamics of information transfer between neurons. Here we describe a neurodevelopmental syndrome caused by germline coding or splice-site variants in UNC13A. The syndrome presents with variable degrees of developmental delay and intellectual disability, seizures of different types, tremor and dyskinetic movements and, in some cases, death in early childhood. Using assays with expression of UNC13A variants in mouse hippocampal neurons and in Caenorhabditis elegans, we identify three mechanisms of pathogenicity, including reduction in synaptic strength caused by reduced UNC13A protein expression, increased neurotransmission caused by UNC13A gain-of-function and impaired regulation of neurotransmission by second messenger signalling. Based on a strong genotype–phenotype-functional correlation, we classify three UNC13A syndrome subtypes (types A–C). We conclude that the precise regulation of neurotransmitter release by UNC13A is critical for human nervous system function.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

UNC13A, the major UNC13 paralog in mammals, is a highly conserved presynaptic protein that is essential for chemical synaptic transmission. It is required for assembly of the SNARE complex that bridges between neurotransmitter-filled synaptic vesicles (SVs) and the plasma membrane, placing SVs in a fusion-competent, ‘primed’ state1,2,3,4,5. UNC13A expression levels are positively correlated with the size of the readily releasable SV pool (the RRP6) and with the signaling strength of synapses7,8,9. During periods of high-frequency synaptic activity, UNC13A supports the resupply of SVs to counterbalance SV consumption10,11,12,13,14, sustaining neurotransmission. UNC13A activity is enhanced through direct binding of Ca2+, Ca2+-calmodulin, Ca2+-phospholipids and diacylglycerol (DAG) to specific regulatory domains. The acceleration of UNC13A activity results in dynamic changes in neurotransmission strength, a phenomenon known as synaptic plasticity10,11,12,13,15,16.

In rodents, Unc13a is expressed in the vast majority of neuronal subtypes and in some cells of neural lineage17,18. Most neuronal subtypes additionally express the paralogs Unc13b and/or Unc13c17, which have similar functions. Mice that constitutively lack Unc13a die shortly after birth19,20 owing to a 90% loss of the RRP at excitatory synapses19. The combined elimination of Unc13a/Unc13b results in a complete block of neurotransmission at both excitatory and inhibitory synapses owing to complete RRP loss20. Consequently, newborn Unc13a/b double knockout (DKO) mice are paralyzed but have intact nervous system development20,21.

A pivotal role for UNC13A in human neurological disorders is emerging. Two patients harboring homozygous truncating variants in UNC13A showed profound developmental delay and died during early childhood22,23. Another patient harboring a de novo missense variant (P814L) in UNC13A exhibited mild intellectual disability, dyskinesia and intention tremor24. Certain deep intronic single-nucleotide polymorphisms contribute to genetic risk for the neurodegenerative conditions amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and frontotemporal dementia (FTD)25,26,27, and promote ALS/FTD disease progression26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33. Recent studies identified reduced UNC13A expression in neurons with ALS/FTD pathology owing to TDP-43-mediated alterations in splicing34,35, but the mechanisms linking reduced UNC13A expression to disease progression remain unknown33,36.

We identified a neurodevelopmental syndrome caused by variants in the UNC13A gene. Systematic patient and variant characterization enabled classification of three disease subtypes. Patients with a type A condition present with profound global developmental delay (GDD) and early-onset seizures. These patients harbor biallelic loss-of-function missense, truncating or splice-site variants that lead to a >50% reduction of UNC13A expression and to a severe reduction in neurotransmission strength in experimental models. Patients with a type B condition exhibit developmental delay, particularly speech delay, and ataxia, tremor or dyskinetic movements as hallmarks of the condition. These patients harbor de novo missense variants that result in a gain of UNC13A function, leading to enhanced neurotransmission. The type C condition is caused by a familial heterozygous missense variant that results in altered regulation of UNC13A function. The patients are mildly affected, exhibiting learning difficulties to mild–moderate intellectual disability and seizures.

Overall, we demonstrate that UNC13A disease-causing variants operate in a cell-autonomous fashion to change synaptic strength and plasticity. Importantly, we present evidence that reduction of UNC13A protein expression to 20–30% of wild-type (WT) levels strongly impairs synaptic transmission and plasticity and has severe consequences in humans, a finding that may be important to understand the role of UNC13A in ALS and FTD. The mechanisms identified here may inform the development of therapeutic approaches.

Results

A neurodevelopmental syndrome caused by pathogenic UNC13A variants

We identified diverse UNC13A variants in 48 index patients presenting with neurodevelopmental deficiencies (Supplementary Data 1). Based on genotype–phenotype-functional assessment, we classified variants in 20 patients as pathogenic (Fig. 1a) and in eight patients as (likely) benign. Variants in 20 patients remained of uncertain significance (Supplementary Data 1 and Extended Data Fig. 1).

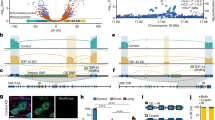

a, Location of validated pathogenic variants identified in 20 patients (Supplementary Data 1) mapped on a schematic representation of the UNC13A gene (NM_001080421.2). Variants with biallelic inheritance are in magenta (p.T117Rfs*18 and p.R202H, and c.767+1 G > T and c.4073+1 G > A are in a compound heterozygous state; others are in a homozygous state), heterozygous de novo variants are in black and a heterozygous, inherited variant is in brown. Variants p.G808D and p.P814L were detected in four and six patients, respectively. Exon colors correspond to the color of protein domains in b. b, Validated pathogenic missense variants overlaid on a schematic representation of the UNC13A protein. The sequence of the hotspot region, termed here as the ‘UNC13 hinge’, is magnified. c, UNC13A tolerance landscape generated based on the observed missense and synonymous variants in gnomAD and corrected for the sequence composition (MetaDome database37). The degree of tolerance for missense variants is color-coded (lowest scores, red, highly intolerant; highest scores, blue, highly tolerant). d, AlphaMissense scores38 plotted for all missense variants (pathogenic, of uncertain significance (VUS) and (likely) benign) reported in this study (Supplementary Data 1; heterozygous de novo missense variants, bold typeface; heterozygous inherited or biallelic variants, non-bold typeface; validated pathogenic variants, red; VUS, gray; validated (likely) benign, blue). Notably, all validated pathogenic variants reported in this study are within the pathogenic AlphaMissense score range, and three out of four validated benign variants fall within the benign score range. We consider VUS variants in the pathogenic AlphaMissense score range as hot VUS (14 variants) and those within the benign/ambiguous score range as cold VUS (12 variants). e, Left: age of patients (with median and interquartile range; error bars, s.d.) at the latest physician visit, stratified by inheritance pattern. Middle: major clinical features of 20 patients with pathogenic variants (Supplementary Data 1), stratified by inheritance pattern. The presence or absence of features is shown by the indicated colors together with the respective percentage for different inheritance patterns. Right: standard deviation scores for growth parameters of patients with pathogenic variants at birth and at the latest visit are illustrated by inheritance pattern (HC, head circumference).

A first group of six patients (18 months to ~15 years old; Fig. 1a,b (magenta), Supplementary Data 1 and Extended Data Figs. 2 and 3) presented with severe-to-profound GDD or intellectual disability, hypotonia and seizures of different types (largely controllable with medication) or death in early childhood caused by respiratory failure after pneumonia in one case. UNC13A variants in these patients were homozygous or compound heterozygous missense, insertion–deletion or splice-site variants with gene-disrupting splicing effects proven by minigene assays (Supplementary Data 1 and Extended Data Figs. 2 and 3). Notably, parents of patients with biallelic variants in this study who were heterozygous carriers of loss-of-function missense or gene-disrupting splice-site variants, and parents of an individual in a previously published case22 with a homozygous gene-disrupting variant were all reportedly healthy, demonstrating possible tolerance to heterozygous loss-of-function UNC13A variants, as has also been shown in mice19.

A second group of 13 patients (21 months to 32 years old; Fig. 1a,b (black) and Supplementary Data 1) harbored pathogenic, heterozygous de novo missense variants with multiple substitutions at amino acids 808, 811 and 814. They presented with variable degrees of GDD, hypotonia, seizures of different types (mainly refractory to treatment) and typically exhibited ataxia, tremor or dyskinetic movements rarely observed in other patients (Supplementary Data 1 and Supplementary Videos 1 and 2). The protein region spanning the seven highly conserved amino acids 808–814 forms a hotspot for an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance and is predicted to be highly intolerant to variation based on the MetaDome database37 and AlphaMissense scores38 (Fig. 1c,d). We term this region the ‘UNC13 hinge’ because it links a regulatory domain cluster with the MUN domain, which mediates SNARE complex assembly39,40 (Fig. 1b).

The third group of patients consisted of a family with at least four affected members across two generations (4 years to 35 years old; Fig. 1a,b (brown) and Supplementary Data 1) harboring a pathogenic heterozygous missense variant (C587F) that caused learning difficulties to mild–moderate intellectual disability as well as controlled seizures. The relatively mild presentation of this variant led to autosomal dominant familial heritability.

Altogether, pathogenic variants in UNC13A cause a spectrum of neurodevelopmental deficiencies (Fig. 1e; mainly GDD or intellectual disability, hypotonia, seizures and abnormal movement features) with both autosomal dominant (de novo or inherited) and recessive inheritance, depending on the type and location of the variants. Additionally, we identified de novo heterozygous or biallelic variants of uncertain significance scattered throughout the UNC13A protein sequence (Extended Data Fig. 1 and Supplementary Data 1). Although many of these variants are high-level (hot) candidates for impacting protein function based on in silico predictions (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Data 1), reliable readouts proving their pathogenicity are currently unavailable.

Characterization of UNC13A variant pathogenicity

UNC13A is a multidomain protein (Fig. 1b) impacting diverse synaptic transmission properties7,10,11,12,13,14,15,19,24. We selected a subset of variants with substitutions at key UNC13A domains (Fig. 2a) and comprehensively characterized their impact on synapse function. We show that variants E52K, R202H, C587F, G808D/C and P814L are pathogenic, while our assays did not detect phenotypic changes for R799Q and N1013S, which we therefore classify as (likely) benign (Supplementary Data 1–3 and Extended Data Fig. 4). A comparative summary of all genetic, clinical and experimental data is presented in Extended Data Fig. 5.

a, Location of studied variants within the UNC13A protein domains (not drawn to scale). b, Schematic representation of the autaptic cell culture system used in this study. c, Left: example images of cultured autaptic hippocampal neurons from Unc13a/b DKO mice that were transfected on DIV 2–3 with UNC13A–GFP cDNA encoding WT or disease-related variants and stained with antibodies against the presynaptic marker VGLUT1, the postsynaptic marker Shank2, the dendritic marker MAP2 and with an antibody against GFP (n = 24–37). Right: magnification of the regions indicated by the white boxes in the merged image. d, Quantification of VGLUT1–Shank2 juxtapositioned puncta per neuron. NT, not transfected. e, Fraction of VGLUT1–Shank2 juxtapositioned puncta where UNC13A–GFP co-staining was detected. Bars and circles in d and e represent means and values for individual neurons, respectively; error bars, s.e.m. The P values in e refer to pairwise comparisons of mean fractions with WT using Dunn’s multiple comparison test. f, Cumulative probability distributions of UNC13A–GFP intensities at VGLUT1–Shank2 juxtapositioned puncta, reporting relative UNC13A expression levels at individual synapses. For each cell analyzed, the mean Munc13 intensity over all synapses was obtained and, subsequently, the pooled mean was calculated for each genotype (Supplementary Data 2). a.u., arbitrary units. The P values in f refer to pairwise comparisons of mean intensities with WT using Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. See Supplementary Data 2 for further details.

UNC13A amino-terminal disease variants reduce UNC13A protein levels

Neurodevelopmental disorders have been linked to deficiencies in synapse development41. To examine whether UNC13A variants affect synaptogenesis or presynaptic UNC13A abundance, we cultured hippocampal neurons from Unc13a/b DKO mice in a microisland culture system42,43 (Fig. 2b), where single neurons grow on astrocytic islands, making synapses onto themselves (‘autapses’). We re-introduced WT rat Unc13a cDNA (UNC13AWT; ~94% identity with human UNC13A) or UNC13A cDNA encoding disease-related variants using lentiviral transduction44 at day in vitro (DIV) 2–3. Following immunocytochemical labeling, synapses were defined as VGLUT1-positive puncta (a presynaptic marker) colocalizing with Shank2-positive puncta (a postsynaptic marker). We found no significant change in the number of formed synapses between the different conditions (Fig. 2c,d and Supplementary Data 2). We then quantified the fraction of VGLUT1–Shank2 puncta exhibiting UNC13A immunoreactivity (Fig. 2c,e and Supplementary Data 2). UNC13AWT was detected in 93.4 ± 1.75% of the VGLUT1–Shank2-positive puncta, and similar colocalization levels were detected for UNC13A with variants in the Ca2+-phospholipid binding C2B domain (UNC13AR799Q), UNC13A hinge (UNC13AG808D) and MUN domain (UNC13AN1013S). Neurons expressing a UNC13A variant in the DAG-binding C1 domain (UNC13AC587F) exhibited a mild but statistically significant reduction in the degree of colocalization. Remarkably, neurons expressing either of the two amino-terminal variants, UNC13AE52K and UNC13AR202H, displayed a strong reduction in the fraction of synapses co-labeled for UNC13A (35 ± 3.9% and 32.5 ± 4% of WT levels, respectively). Moreover, substantially weaker UNC13A labeling intensities were evident (UNC13AE52K, 23 ± 11% of WT levels; UNC13AR202H, 20 ± 13% of WT levels; Fig. 2f and Supplementary Data 2). Taken together, UNC13A disease variants do not affect synapse number in vitro, but the E52K and R202H substitutions cause a strong reduction of synaptic UNC13A levels.

UNC13A amino-terminal disease variants cause reduced neurotransmission

E52 is located at the interaction interface between the UNC13A C2A domain and RIMS1/RIMS2 (refs. 45,46,47,48) (Fig. 3a,b), while R202 is part of an intrinsically disordered region (IDR; amino acids 151 to ~450; Fig. 1a). The E52K and R202H disease variants are inherited in an autosomal recessive manner and cause a severe disorder (Fig. 3c,d). Expression of UNC13AE52K or UNC13AR202H in HEK293 cells, which lack UNC13A but express the misfolded protein detection machinery, showed no evidence that these variants cause inherent protein instability (Extended Data Fig. 6).

a, Amino acid sequence alignment of the C2A domain and adjacent region for UNC13A homologs in different species (disease variants are highlighted by a bar; E52K, orange; R202H, green; HS, Homo sapiens; RN, Rattus norvegicus; CE, C. elegans). b, Structure of the UNC13A C2A domain (orange) in complex with the RIM zinc-finger domain (blue) (PDB 2CJS)72. E52 is shown in a space-filled presentation. c, Pictures of three patients with pathogenic homozygous amino-terminal variants, showing narrow forehead, highly arched eyebrows, impression of hypertelorism, depressed nasal bridge, small nasal tip and underdeveloped, anteverted ala nasi, long philtrum, impression of retrognathia and large, mildly forward-facing earlobes. d, Representative pedigrees of patients with pathogenic biallelic amino-terminal variants, illustrating an autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance with apparently healthy carrier parents. e, Schematic illustration of electrophysiological recordings in autaptic neurons. f, Constructs used in electrophysiological experiments in g–m (NLS; nuclear localization signal). g–m, Characterization of synaptic transmission in autaptic hippocampal neurons expressing UNC13AWT (black), UNC13AE52K (orange) or GFP-NLS (gray). Example traces (g) and summary data showing mean frequencies (h) of mEPSCs. Example traces (i) and summary data showing mean charges (j) of eEPSCs. Example traces (k) and summary data showing mean charges (l) of sucrose-evoked EPSCs as a measure of RRP size. No eEPSCs were elicited in UNC13AE52K-expressing neurons during high-frequency AP trains (40 Hz) (m). n, The constructs used in electrophysiological experiments in o–v. Example traces (o), mean amplitudes (p) and mean frequencies (q) of spontaneously occurring mEPSCs in neurons expressing UNC13AWT (black) and UNC13AR202H (green). r,s, Example eEPSC traces (r) and mean eEPSC charge (s). Smaller sucrose-evoked EPSCs (t) indicate a reduced RRP size in UNC13AE52K-expressing neurons (u), while the mean vesicular release probability was unchanged (v). Data were obtained from at least three independent cultures per condition. Statistical analysis: Kruskal–Wallis test (g–m) and two-tailed Mann–Whitney test (o–v). In h, j, l, p, q, s, u and v, bars and circles represent means and values for individual neurons, respectively; error bars, s.e.m. See Supplementary Data 3 for further details.

To assess how variants affect synaptic transmission, we conducted whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings in autaptic Unc13a/b DKO glutamatergic hippocampal neurons (Fig. 3e)20,42 transfected with UNC13AWT or UNC13A carrying disease variants. In UNC13AE52K-expressing neurons (Fig. 3f), we could not detect spontaneous miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) or action potential (AP)-evoked excitatory postsynaptic currents (eEPSCs; Fig. 3g–j and Supplementary Data 3). Application of hypertonic sucrose solution to assess the size of the RRP6 revealed the absence of a measurable RRP in UNC13AE52K neurons, indicative of a severe SV priming deficit (Fig. 3k,l). Given that high-frequency AP firing can enhance UNC13A activity, we delivered trains of 40 APs at 40 Hz frequency but did not detect synaptic currents throughout the trains (Fig. 3m). Together, we conclude that UNC13AE52K does not rescue synaptic transmission to measurable levels.

By contrast, UNC13AR202H expression (Fig. 3n) rescued synaptic transmission, albeit with lower efficacy than UNC13AWT. Mean frequency and amplitude of mEPSCs were similar to those measured in neurons expressing UNC13AWT (Fig. 3o–q), but the average eEPSC size (Fig. 3r,s) and RRP charge (Fig. 3t,u) were both reduced by ~40%. The mean vesicular release probability (\({\bar{p}}_{\mathrm{vr}}\)), calculated as the charge transfer during a single AP-induced eEPSC divided by the charge transfer in response to sucrose-evoked RRP release, was unaltered (Fig. 3v).

Taken together, these results demonstrate that two variants cause lower synaptic UNC13A abundance and reduced synaptic strength in mouse neurons. Affected patients presented with profound GDD and no motor development (Figs. 1e and 3c), consistent with decreased synaptic efficacy observed in vitro. Interestingly, although both substitutions reduce UNC13A levels to similar extents (Fig. 2e,f), UNC13R202H expression partially rescues synaptic transmission, while UNC13E52K expression does not. This probably reflects the combined effect of lower UNC13A protein levels and functional consequences of the E52K exchange on the C2A domain function47. The substantial neurotransmission in UNC13R202H-expressing neurons indicates that very low UNC13A levels are sufficient for synapse function.

UNC13A hinge variants cause a gain-of-function in neurotransmission

We identified 13 patients with de novo variants in the UNC13A hinge (Fig. 4a–d). We previously reported one patient with an UNC13A P814L variant24, causing a gain-of-function in synaptic transmission. To consolidate variant pathogenicity and establish functional causality between the expression of hinge variants and synaptic transmission properties, we studied the frequently affected residue G808 (Fig. 4a,d).

a, A sequence alignment of UNC13A homologs illustrating that the UNC13 hinge domain is conserved (residues found mutated in patients in bold). b, Facial portraits of patients with pathogenic de novo hinge variants, displaying high anterior hairline with an appearance of tall forehead, impression of hypertelorism, deeply set eyes, attached earlobes, smooth, rather short philtrum, thin upper lip vermilion, everted lower lip vermilion, bulbous nasal tip and retrognathia. c, Representative pedigrees of patients with pathogenic de novo variants, illustrating an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance. d, Crystal structure of the UNC13A (PDB 5UE8) identifies the UNC13A hinge as non-structured (purple), connecting two structured domains. e–l, Characterization of synaptic transmission in autaptic hippocampal neurons expressing UNC13AWT (gray) or UNC13AG808D (blue). Example traces (e) and summary data showing mean amplitudes (f) and mean frequencies (g) of mEPSCs. Example traces (h) of sucrose-evoked EPSCs and summary plots of the measured RRP size (i). Example traces (j) of eEPSCs and summary plots of eEPSC charge (k) and vesicular release probability (l). m, Schematic illustration of the aldicarb assay in C. elegans. Aldicarb-induced accumulation of ACh in the extrasynaptic space leads to receptor desensitization and to worm paralysis. Synaptic phenotypes associated with ACh hypersecretion lead to faster ACh accumulation and to faster paralysis. Reduced secretion results in slower paralysis. n, CRISPR-generated heterozygous (green) and homozygous (blue) knock-in UNC-13P814L (UNC-13P956L) worms exhibit faster aldicarb-induced paralysis than WT worms. o, Similar results obtained in heterozygous (green) or homozygous (blue) UNC-13G808C (UNC-13G950C) knock-in worms. Statistical analysis was performed by using a two-tailed Mann–Whitney test (f, g, i, k, l) or Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s test (n, o). Bars and circles in f, g, i, k and l represent means and values for individual neurons, respectively; error bars, s.e.m. Data were obtained from at least three independent cultures per condition. Circles in n and o represent averaged data from >10 worms. See Supplementary Data 3 for further details.

In autaptic hippocampal Unc13a/b DKO neurons expressing UNC13AG808D–GFP, we observed a greater than twofold increase in the frequency of mEPSCs compared to neurons expressing the WT variant, whereas mEPSC amplitudes were unaltered (Fig. 4e–g). Given that larger RRP size could underlie an increased mEPSC frequency, we estimated the RRP sizes and found similar values in UNC13AG808D-expressing and UNC13AWT-expressing neurons (Fig. 4h,i). Together, these findings are consistent with the notion that RRP SVs in resting UNC13AG808D-expressing neurons are more likely to fuse spontaneously, possibly indicating higher SV fusogenicity49 or a larger fraction of ‘tightly-docked’ SVs50. UNC13AG808D-expressing neurons also showed significantly larger eEPSC charges (Fig. 4j,k). Given that the average mEPSC charge and RRP size were unaltered (Fig. 4f,i), the increased eEPSC charge is indicative of a larger fraction of the RRP released by single APs (higher \({\bar{p}}_{\mathrm{vr}}\); Fig. 4l). We conclude that UNC13AG808D leads to a gain-of-function in spontaneous and evoked neurotransmission.

Given that all UNC13A hinge variants were heterozygous, we tested whether a gain-of-function phenotype prevails in the presence of a WT allele. We generated homozygous and heterozygous C. elegans strains harboring the G808C and P814L substitutions using CRISPR–Cas9 targeting of the unc-13 gene. The C. elegans and human UNC13A protein products are highly homologous (~50% identity, ~70% sequence similarity) and serve similar functions51,52,53,54. As a behavioral readout of synaptic function, we assayed loss of movement in response to exposure to the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor aldicarb (Fig. 4m), with faster paralysis indicating acetylcholine hypersecretion. Compared with WT worms, paralysis occurred significantly faster and to a similar extent in homozygous and heterozygous G808C and P814L mutant worms (Fig. 4n,o (green and blue)). These data are consistent with a gain-of-function in acetylcholine secretion, also in the presence of a WT allele.

Based on these results, we conclude that UNC13A hinge variations increase the degree of spontaneous and evoked neurotransmission. Given the substantial number of patients, and because the functional phenotypes of neurons expressing UNC13AP814L and UNC13AG808D in mouse neurons and G808C and P814L in C. elegans are nearly identical (Extended Data Fig. 5), we conclude that UNC13A hinge variations are pathogenic and act through a similar mechanism.

A familial variant in the UNC13A C1 domain

We identified four patients harboring a heterozygous missense variant (c.1760_1761delinsTT; C587F) in the UNC13A DAG-binding C1 domain (Fig. 5a–d)15,55. In cultured WT synapses, the membrane-permeable DAG analog Phorbol 12,13-dibutyrate (PDBu) causes a greater than twofold increase in synaptic strength within seconds after application15,56. To test whether C587F hampers DAG sensing, we used a protein-translocation assay. In HEK293 cells, overexpressed UNC13AWT–GFP undergoes translocation to the plasma membrane upon PDBu application (Fig. 5e,f). A C1 domain point mutation, H554K, blocks this translocation14 (Fig. 5e,f). We found that the disease variant C587F blocks UNC13A translocation, while other variants in this study exhibit WT-like behavior (Fig. 5e).

a, Sequence alignment for UNC13 paralogs highlighting H554 (blue) and C587 (bold). Lines below indicate Zn2+-coordinating residues. b, Facial portraits of index patient 6, his father and aunt, carrying the pathogenic variant, displaying a high, broad forehead, impression of hypertelorism, deeply set eyes, fullness of the upper lateral eyelid, depressed nasal bridge, underdeveloped ala nasi and small nasal tip, smooth, broad philtrum and everted vermilion of the upper lip. c, A four-generation pedigree, with four individuals confirmed as harboring c.1760 G > T, p.(C587F). d, The C1 domain structure (top) and a zoomed-in view of one Zn2+-binding pocket. The corresponding amino acid numbers in the rat UNC13A are given in brackets. e, HEK293FT cells transiently transfected with UNC13A–GFP constructs encoding WT or patient variants, treated with 1 µM PDBu for 1 h (scale bar, 5 µm; n = 10–15 per condition; white arrowheads highlight UNC13A location (green)). f, Quantification of the cytosolic GFP signal in the presence or absence of PDBu. g–n, Characterization of synaptic transmission in autaptic hippocampal neurons expressing UNC13AWT (gray) or UNC13AC587F (red). Example traces (g) and summary plots showing mean amplitude (h) and mean mEPSC frequency (i). Example traces (j) and summary plots showing mean eEPSC charge (k). Example traces (l) and summary plots showing mean sucrose-evoked EPSC charge (m). n, Quantification of vesicular release probability. o, Time to paralysis in CRISPR-targeted C. elegans worms carrying a homozygous C587F (C729F) variation and exposed to aldicarb. p,q, Example eEPSCs before and after application of PDBu in neurons expressing UNC13AWT (p) or UNC13AC587F (q). r, The average time courses of eEPSC amplitude change. s,t, Similar data for UNC13AG808D (s, blue) or UNC13AR202H (t, green). In o and r–t, circles represent an average from >10 worms or an average of the indicated number of neurons. Bars and circles in f, h, i, k, m and n represent means and values for individual neurons, respectively. Data were obtained from at least three independent cultures per condition; error bars, s.e.m. Statistical analysis was performed by using a two-tailed Mann–Whitney test (f, h, i, k, m, n) or Wilcoxon test (o). See Supplementary Data 3 for further details.

We then characterized synaptic transmission and DAG responsiveness in autaptic neurons expressing UNC13AC587F (Fig. 5g–n and Supplementary Data 3). Basal spontaneous and AP-evoked synaptic transmission were largely similar in Unc13a/b DKO neurons expressing UNC13AC587F or UNC13AWT. This is consistent with a similar time course of aldicarb-induced paralysis in homozygous C587F worms and WT worms (Fig. 5o). However, PDBu failed to potentiate eEPSC amplitudes in autaptic neurons (Fig. 5p–r), in agreement with the absence of PDBu-induced translocation (Fig. 5f). We conclude that the UNC13AC587F variation acutely changes the responsiveness of UNC13A to DAG signaling, while not strongly interfering with basal synaptic transmission (see Extended Data Fig. 7 for molecular dynamics simulation data).

Finally, we tested whether other disease variants impair the PDBu-induced synaptic potentiation. Expression of UNC13AG808D, with a presumably intact C1 domain (Fig. 5e), resulted in little PDBu-induced potentiation (~20% of WT; Fig. 5s). Conversely, neurons expressing R202H exhibited a tendency towards stronger PDBu-induced potentiation than UNC13AWT-expressing neurons (Fig. 5t). This is probably a consequence of already altered basal synaptic transmission properties: synaptic strength is enhanced in neurons expressing UNC13AG808D, which may partially occlude PDBu potentiation. By contrast, neurons expressing UNC13AR202H exhibit lower basal synaptic strength, which may allow stronger potentiation. These data suggest an unbalanced DAG signaling in UNC13AG808D-expressing and UNC13AR202H-expressing neurons.

UNC13A variants alter short-term synaptic plasticity

During repetitive activation, synapses exhibit short-term plasticity (STP)57, a use-dependent alteration of synaptic strength on a time scale of milliseconds to minutes. STP occurs when fusion-competent SVs are progressively consumed. UNC13A-mediated SV priming and its modulation by second messengers counteracts SV depletion10,11,12,13, thus shaping STP. We next studied how disease variants in UNC13A affect this process.

We recorded eEPSCs during high-frequency trains, embedded in low-frequency stimulation (Fig. 6a,e), and observed strong changes during and after stimulus trains (Fig. 6b–d,f–h): in neurons expressing UNC13AC587F or UNC13AG808D, prominent short-term synaptic depression of eEPSC amplitudes was observed (Fig. 6c,d,g,h (gray arrow)), whereas UNC13AR202H-expressing neurons typically exhibited short-term synaptic enhancement (Fig. 6b and Extended Data Fig. 8). To explore underlying mechanisms, we quantified the replenishment rate constants of the RRP during 40 Hz AP trains, based on a single-pool model of SV priming12,58. RRP replenishment rate constants were reduced for neurons expressing UNC13AC587F or UNC13AG808D but tended to be accelerated in UNC13AR202H-expressing neurons (Fig. 6i).

a–d, Stimulation protocol (a) and average time courses of normalized eEPSC amplitudes recorded in autaptic hippocampal neurons expressing UNC13AWT (gray) or UNC13AR202H (b, green), UNC13AC587F (c, red) or UNC13AG808D (d, blue), before, during and after a 10 Hz train consisting of 30 APs. e–h, Average time courses of normalized eEPSC amplitudes recorded before, during and after a 40 Hz train consisting of 40 APs (e) in neurons expressing UNC13AWT (gray) or UNC13AR202H (f, green), UNC13AC587F (g, red), or UNC13AG808D (h, blue). Gray arrowheads mark the time point during which steady-state depression was quantified, and black arrowheads mark the first eEPSC following the train, used to estimate the magnitude of augmentation. i, Replenishment rate constants calculated based on a single-pool model of SV priming for neurons of the indicated genotypes. j,k, Magnitude of eEPSC augmentation after conditioning 10 Hz (j) or 40 Hz (k) stimulation. Data were obtained from at least three independent cultures per condition. Statistical analysis was performed by using a two-tailed Mann–Whitney test (i–k). Bars and circles in i–k represent means and values for individual neurons, respectively; error bars, s.e.m.

Following AP trains, synaptic strength can transiently increase (Fig. 6b–d,f–h (black arrowheads)). We quantified such augmentation by measuring eEPSCs 2 s after the cessation of AP trains. Compared to UNC13AWT-expressing neurons, augmentation was significantly stronger when UNC13AR202H was expressed, whereas it was virtually absent in neurons expressing UNC13AC587F or UNC13AG808D (Fig. 6j,k and Extended Data Figs. 5 and 8).

Collectively, these data demonstrate that UNC13A disease variants have a complex impact on STP. Reduced UNC13A expression favors facilitation of synaptic responses during and strong augmentation after an AP train, while gain of UNC13A function or diminished UNC13A PDBu/DAG regulation leads to increased depression during and reduced augmentation after AP trains.

Discussion

We report the identification of a neurodevelopmental syndrome caused by pathogenic UNC13A variants that cause cell-autonomous changes to synaptic transmission and plasticity. The UNC13A syndrome joins the group of SNAREopathies that arise from pathogenic variants in the core proteins mediating neurotransmitter release (Extended Data Fig. 5a,b). The most common SNAREopathy is the STXBP1 encephalopathy, which is diagnosed in 3.3–3.8 out of every 10,000 births59,60. STXBP1 encodes the MUNC18-1 protein, a functional interactor of UNC13A in SNARE complex assembly61,62,63.

Based on the genetic, clinical and functional evidence presented here (Extended Data Fig. 5c), we propose a categorization of the UNC13A syndrome. Type A comprises variants that cause full or partial UNC13A protein loss. This type is caused by biallelic missense (Fig. 3), splice-site (Extended Data Figs. 2 and 3) and nonsense variants based on our cohort and a few previously published cases22,23. These variants lead to profound GDD in all cases, and in some, cause death in early childhood owing to respiratory failure after pneumonia (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Data 1). All patients develop early-onset seizures that mostly respond to treatment. Based on a previously reported case23 in which an individual was diagnosed with fatal myasthenia according to electromyography findings, and based on patients 3 and 7 in our study (Supplementary Data 1 and Extended Data Figs. 2 and 3), we suggest considering myasthenic presentation in type A patients. Type A variants are associated with eliminated or strongly reduced UNC13A expression, weaker synaptic transmission under basal and low-frequency activity (Fig. 3) and a tendency towards enhanced synaptic responses during and after AP trains, or by DAG signaling (Figs. 5 and 6). We speculate that these variants impair UNC13A transport and/or active zone recruitment.

The type B UNC13A condition comprises variants that cause an UNC13A gain-of-function. This type is caused by de novo heterozygous missense variants in the UNC13A hinge (G808D, G808C, G808V, K811E, P814L) (Figs. 1 and 4) and is characterized by developmental delay, primarily in speech acquisition and, to a lesser extent, in motor skills. The overall severity of the developmental delay is less than that observed in type A, and no death in early childhood is reported. Epileptic seizures are severe and become refractory to treatment in most cases. A hallmark of this condition is ataxia and tremor or dyskinetic movements24 (Fig. 1e, Supplementary Videos 1 and 2). As UNC13A is also expressed in motoneurons, it remains to be determined whether the imbalanced synaptic transmission at the neuromuscular junction contributes to this presentation. Functionally, type B variants cause a gain-of-function of synaptic transmission during spontaneous and low-frequency AP activity (Fig. 4), strong short-term synaptic depression and diminished augmentation during and after high-frequency activity (Fig. 6), as well as diminished potentiation by DAG signaling (Fig. 5).

Finally, the type C condition comprises a variant that results in UNC13A dysregulation. This type is caused by a familial heterozygous missense variant in the UNC13A C1 domain (C587F; Figs. 1 and 5), presenting with mild delay in speech development, learning difficulties to mild–moderate intellectual disability and controlled seizures (Supplementary Data 1). Neurons expressing this variant show near-normal synaptic transmission in response to low-frequency AP activity, but absent potentiation by DAG signaling (Fig. 5) and aberrant STP patterns during and after high-frequency activity (Fig. 6).

We anticipate additional pathogenic variants and disease subtypes to emerge. In particular, loss of function without loss of protein is expected for variants that interfere with UNC13A function in SNARE complex assembly (for example, in the MUN or C2C domain), which may lead to a type A-like condition. Based on AlphaMissense scores and the rareness of variants in the hinge region (frequency in gnomADv4.1 database), almost all possible hinge amino acid exchanges (42 out of 45; 93%) show pathogenic predictions, and we anticipate additional variants to arise. UNC13A hyperfunction has been described in structure–function studies46,53,64, and variants in these regions may also lead to a type B condition. Missense or in-frame variants affecting Ca2+ or Ca2+/calmodulin binding may cause a type C condition.

Our functional assays were designed to investigate deficits caused by UNC13A variants and were therefore performed in the absence of a WT UNC13A allele (which is relevant for heterozygous variants) and in the absence of UNC13B/C. Co-expression of UNC13A/B/C is expected to modify the functional phenotypes we describe in a synapse-specific fashion, but to what extent is hard to predict and requires further experimentation. UNC13B and UNC13C are expressed alongside UNC13A in distinct neuronal subtypes of the cerebellum (UNC13C) and of the cortex and hippocampus (UNC13B)17. Interestingly, UNC13B expression can fully compensate for UNC13A loss in hippocampal inhibitory neurons, but UNC13B/C can only marginally compensate for UNC13A loss (<10%) in excitatory hippocampal synapses20,65. Reasons for the limited redundancy remain unclear and may involve active zone recruitment mechanisms66,67. Nonetheless, following full or partial loss of UNC13A (type A), co-expression of UNC13B may support synaptic transmission in inhibitory neurons to a larger extent than in excitatory neurons, shaping the inhibition-to-excitation ratio within neuronal networks. It is tempting to speculate that this might underlie the favorable response of epileptic seizures to medication in type A patients. In the type B condition, we demonstrated that UNC13AP814L exerts a similar effect in excitatory hippocampal and inhibitory striatal neurons24 and that the magnitude of the functional gain is similar in the presence or absence of UNC13AWT (Fig. 4n,o).

A key finding in this study is the identification of variants that reduced UNC13A expression levels below 50% of WT levels (E52K, R202H and, probably, some splice-site variants). Reduction of UNC13A expression levels has been recently highlighted as a pathogenic mechanism in ALS and FTD. In healthy neurons, TDP-43 acts as a splicing regulator for UNC13A mRNA34,35,68, in which it represses the inclusion of a cryptic exon. In neurons with ALS or FTD pathology, TDP-43 is depleted from the nucleus69, resulting in the inclusion of the cryptic exon in up to 100% of the UNC13A mRNA, and thus in lower UNC13A protein levels34,35. Deep intronic UNC13A variants that possibly change the cryptic exon’s splicing propensity pose a strong genetic risk for ALS/FTD disease and disease progression25,27,34,35. How reduced UNC13A levels enhance ALS/FTD pathology remains to be established, and the minimal UNC13A levels required for proper synaptic function have not yet been determined. Several observations made here shed light on these issues.

We report that the R202H substitution severely interferes with human motor function (Fig. 1e), leads to reduced UNC13A expression levels (20–30% of WT levels; Fig. 2) and impairs synaptic function (Figs. 3, 5 and 6, and see ref. 70). Although we cannot exclude that R202H has additional effects on UNC13A function in addition to reducing its expression levels, these data suggest that altered neurotransmission may accompany ALS/FTD cellular pathology as UNC13A levels decline and potentially exacerbate disease symptoms. However, we also note that 20–30% of UNC13A expression levels are already sufficient to support ~60% of neurotransmitter release in cultured neurons and that patients with low UNC13A expression levels have improved survival chances compared with patients with no functional UNC13A, who die in early childhood22,23. Together, we propose that therapeutic strategies that stabilize 20–30% as minimal UNC13A expression may already be beneficial. Given that UNC13A haploinsufficiency appears to be tolerated in humans (refs. 22,23 and this study) and in mice19, restoration of UNC13A to levels approaching 50% appears to be sufficient as an upper target. Antisense oligonucleotide therapies71, for example, are approved for clinical use and could be well-used in ALS/FTD and in patients with type B and C neurodevelopmental disorders. In the latter, antisense oligonucleotides that exclusively suppress the expression of pathogenic transcripts and increase the relative abundance of the WT protein variant may improve disease symptoms. Our study underscores the importance of an experimentally validated mechanistic understanding of pathogenicity for diverse variants in the same gene, as different therapeutic strategies should be used to combat them.

Methods

Study approval

This study was performed as part of a research study approved by the ethics commission of the Canton of Zurich (ID PB_2016-02520 (SIV 11/09)). In addition, for each patient, ethical approvals and informed consent forms from parents or guardians were obtained by the respective research teams and institutions for data use and publication, including photographs or videos where applicable. Participants did not receive compensation. The use of Unc13a/b knockout mice was approved by the responsible local government organization (Niedersächsisches Landesamt für Verbraucherschutz und Lebensmittelsicherheit; 33.19-42502-04-15/1817 and 33.19-42502-04-20/3589, and Landesamt für Gesundheit und Soziales; G106/20). Mice (Mus musculus, backcrossed to a C57BL/6N background) of embryonic day 18 or postnatal day 0–1 and of both sexes were used in electrophysiological experiments. Each culture was obtained from one or more mice, and two to four independent cultures were used per condition. Adult mice were kept under IVC/SPF conditions, on a 12 h light, 12 h dark cycle, at room temperature (22 ± 2 °C) and humidity levels of 55 ± 10%.

Patient identification and characterization

Individuals included in this study underwent exome or genome sequencing on diverse sequencing platforms on a clinical or research basis in academic institutes or diagnostic labs worldwide. Using GeneMatcher73 and personal communication with colleagues enabled us to assemble clinical and genetic details on a total of 48 index patients with de novo or inherited heterozygous or biallelic variants in UNC13A (NM_001080421.3), including two previously published cases harboring c.154 G > A, p.(E52K) (case 74 described in ref. 74) and c.4379 C > T, p.(A1460V) (case UPN-0740 described in ref. 75) variants with further follow-up information. Standard deviation of growth parameters was calculated as previously described76. Variant nomenclature was verified using VariantValidator77. De-identified clinical data from collaborating institutions were obtained with local institutional review board approval and informed consent from parents or guardians of affected individuals, including consent for publication of facial photographs for individuals in Figs. 3–5, Extended Data Figs. 1 and 2 and Supplementary Videos 1 and 2.

Minigene splicing assay

For splicing assays, the pSplicePOLR2G3 vector was digested and purified as described previously78. Inserts of UNC13A exons and their flanking intronic regions were amplified using the Q5 HotStar High-Fidelity Taq Polymerase kit (New England Biolabs), and cloning reactions were performed with the In-Fusion HD Cloning kit (Clontech) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. Transient transfection of HEK293T cells was performed with WT and mutated plasmid constructs (1 μg per well) complexed with the jetPEITM transfection reagent (Polyplus Transfection). Total RNA was extracted 48 h post transfection with the NucleoSpin RNA Plus kit (Macherey-Nagel). Reverse transcription was performed with the ProtoScript II First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (New England Biolabs), and fluorescent PCR was performed as described previously79. PCR products were size-separated on a 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Output data were analyzed with Peak Scanner software (Applied Biosystems).

DNA construct and virus preparation

Unless otherwise indicated, cDNA encoding rat UNC13A tagged with EGFP at the carboxy terminus80 was used. Mutated amino acids are indicated throughout the paper according to the human nomenclature, and Supplementary Table 1 lists the respective amino acids mutated in the rat cDNA. Lentiviral preparation was carried out by the Viral Core Facility of the Charité–Universitätsmedizin Berlin (vcf.charite.de). The FUGW vector81, in which the ubiquitin promoter was exchanged with the human synapsin 1 promoter, was used according to a previously published81, modified protocol82, using helper plasmids (Addgene, 8454 and 8455; ref. 44). In a subset of experiments, constructs encoding NLS-GFP-P2A-UNC13A-Flag under the synapsin promoter were used82. In Fig. 5e, pEGFP–N1–UNC13AWT and corresponding mutants were used. Viral transfection of neurons was carried out on DIV 2–3. Plasmid and primer sequence information are summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

Antibodies

Antibodies used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Microisland cultures of mouse hippocampal neurons and electrophysiological recordings

Neurons were prepared from the brains of E18 Unc13a/b DKO mice and plated on WT astrocyte microisland cultures according to published protocols83. Cultures were kept at 37 °C and 5% CO2 until recordings were made at DIV 13–16. Whole-cell voltage-clamp data were acquired using an Axon Multiclamp 700B amplifier, Digidata 1440A data acquisition system and pCLAMP 10 software (Molecular Devices). All recordings were performed using a standard external solution containing 140 mM NaCl, 2.4 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES, 10 mM glucose, 4 mM CaCl2 and 4 mM MgCl2 (320 mOsm l−1). The standard internal solution contained 136 mM KCl, 17.8 mM HEPES, 1 mM EGTA, 4.6 mM MgCl2, 4 mM NaATP, 0.3 mM Na2GTP, 15 mM creatine phosphate and 5 U ml−1 phosphocreatine kinase (315–320 mOsm l−1), pH 7.4. eEPSCs were evoked by depolarizing the cell from −70 mV to 0 mV for a 1 ms duration. Basal eEPSCs were recorded at a frequency of 0.1 Hz. Rapid external solution exchange around individual neurons was achieved by using a custom-made fast-flow system controlled by a stepper motor. Recordings were made at room temperature (~22 °C). The size of the RRP was estimated from the integrated charge of EPSCs evoked by application of 500 mM sucrose (7 s or 5 s in Fig. 3k–l) after subtraction of the steady-state current to correct for ongoing SV pool replenishment. mEPSCs were recorded for 100 s in the presence of 300 nM tetrodotoxin. In Fig. 3g,h, additional recordings in the presence of NBQX (3 μM, Tocris Bioscience) were used to subtract false-positive events from traces recorded in extracellular solution. mEPSC traces were filtered at 1 kHz, and miniature events were identified using a sliding template function in Axograph or in Igor Pro (5–200 pA; rise time, 0.15–1.5 ms; half-width, 0.5–5 ms). PDBu (1 μM) was applied for 1 min. Analyses were performed using Axograph (v.1.4.3) (Molecular Devices) or Igor Pro (Wavemetrics). Data were obtained from at least two cultures, and for the majority of data, from four cultures.

Immunocytochemistry

Quantifications of synapse number, signal intensity and colocalization were made by immunostaining of microisland hippocampal cultures. Lentiviral-transfected samples were briefly washed with PBS and fixed at DIV 13 with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS for 18 min with gentle agitation. After three PBS washes, the remaining PFA was quenched with 50 mM glycine for 10 min, and samples were washed again with PBS. Before permeabilization, samples were treated with four drops of Image-iT FX signal enhancer in 1.5–2 ml PBS per well (in a six-well plate) and maintained shaking for 20 min. Samples were permeabilized for 30 min with 0.1% Triton X-100 and 2.5% normal goat serum (NGS) diluted in PBS while gently shaking. Blocking was performed with 2.5% NGS in PBS, twice for a total of 15 min. The primary antibodies were diluted in blocking solution, and coverslips were mounted upside down on 150 μl antibody solution placed on parafilm and kept for 2.5 h at room temperature or overnight at 4 °C, both in a wet chamber. Coverslips were washed three times with 0.1% Triton X-100 and 2.5% NGS in PBS and subsequently mounted upside down in 150 μl secondary antibody solution in a dark, wet chamber for 45 min at room temperature. Finally, the coverslips were washed five times with 0.1% Triton X-100 and 2.5% NGS in PBS for 2–5 min. The coverslips were briefly washed in double-distilled water, excess water was removed and the coverslips were mounted on a glass slide using Aqua-Poly/Mount.

Image acquisition and analysis

Microislands containing one hippocampal neuron were efficiently localized by first acquiring a low-magnification overview image of the entire coverslip using a Zeiss LSM 880 confocal laser scanning microscope. Specifically, upon 405 nm excitation, a ×10 air objective (0.45 NA) was used to image Alexa Fluor 405-stained MAP2 (410–470 nm). The overview image served as a map based on which the motorized stage of the Zeiss LSM 880 was moved to selected autaptic neurons, from which high-resolution (x, y, z: 208, 208, 309 nm) z-stacks of VGLUT1 (637–758 nm), Shank2 (570–624 nm), UNC13A–eGFP (490–552 nm) and MAP2 (410–470 nm) were acquired with a ×40 oil immersion objective (1.40 NA). Overlapping fields of view for subsequent image stitching were acquired with the above settings, in case the autaptic neuron did not fit in one field of view.

All image processing was conducted with the same automated Imaris (v.9.10.0) batch process. Initially, the respective MAP2 three-dimensional surface was generated, followed by surfaces based on the respective VGLUT1, Shank2 or UNC13A–eGFP signal located within the 0.5 μm MAP2 periphery. Overlapping Shank2 and VGLUT1 surfaces were used to estimate the total number of synapses contacting individual autaptic neurons. Subsequently, the synapses overlapping with the UNC13A–eGFP signal were identified, and in a reciprocal manner, UNC13A–eGFP surfaces that overlap with synapses were identified. The data generated by the Imaris batch process were organized with the KNIME Analytics Platform (v.4.7.1) and further quantified with GraphPad Prism (v.9.0.0). For illustration, representative images were processed with the FIJI software package84 (v.2.14.0/1.54f) and assembled in Adobe Illustrator.

Translocation assay

HEK293T cells were seeded on poly-L-lysine-coated glass coverslips and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 1% MEM, 1% GlutaMAX, 1% penicillin–streptomycin and 10% FBS at 37 °C under 5% CO2. Cells were transfected with UNC13A–GFP cDNA in pEGFP–N1 vector80 carrying the respective disease-related variations under the CMV promoter using Lipofectamine 2000 and 1 μg DNA per well in a six-well plate, according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. After 3.5 h of incubation, the medium was replaced with culture medium, and the cells were incubated overnight. Translocation was induced by applying 1 µM PDBu for 1 h. Cells were washed with PBS, fixed with 4% PFA in PBS at room temperature for 10 min, washed with PBS and treated with 50 mM glycine in PBS for 10 min to quench remaining PFA. Cells were washed in PBS and incubated with 1 µg ml−1 DAPI in PBS at room temperature for 15 min. Cells were then washed again with PBS and mounted using Aqua-Poly/Mount. Fluorescence imaging was performed on a confocal laser scanning microscope (Zeiss LSM710-CONFOCOR3). Excitation wavelengths were 405 nm for DAPI and 488 nm for EGFP.

C. elegans strains and behavioral assays

Strains were maintained and genetically manipulated as previously described85. Animals were raised at 20 °C on nematode growth media seeded with OP50. Control strains used included N2 and unc-13(nu641). unc-13(nu641) harbors a C-terminal mScarlet in the unc-13 locus as described previously86. UNC-13 residue numbering is based on the UNC-13L isoform accession number NP_001021874. CRISPR–Cas9-mediated genome editing was performed to generate the desired genetic modifications in C. elegans. The CRISPR–Cas9 system was implemented using a co-injection strategy with Cas9 protein, CRISPR RNA (crRNAs) and repair templates.

For crRNA design, crRNAs targeting the desired genomic loci were initially designed using the Benchling online tool and custom crRNA design software from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT). crRNAs were selected based on proximity of the cut site to the desired mutation, high on-target efficiency and minimal predicted off-target mutations. crRNAs were ordered from IDT, resuspended in 4 μg μl−1 in nuclease-free water and diluted to a working concentration of 0.4 μg μl−1 before adding to the injection mix.

For Cas9 preparation, recombinant Cas9 protein purchased from IDT (Alt-R S.p. Cas9 Nuclease V3) was stored at −20 °C and used at 0.25 mg ml−1. Trans-activating CRISPR RNA (tracrRNA) was purchased from IDT, diluted to 4 μg μl−1 in IDT nuclease-free duplex buffer and aliquots were stored at −20 °C.

Repair template design

For precise edits, single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides were used as repair templates. These templates included the desired modification flanked by 20–50 bp homology arms and an engineered restriction site. Single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides were ordered from IDT (Ultramer DNA Oligonucleotides).

Injection mix preparation

The injection mix was prepared as follows: 0.5 µl Cas9 protein (10 mg ml−1 stock), 5 µl tracrRNA (0.4 µg µl−1 stock), 2.8 µl mutant crRNA (0.4 µg µl−1 stock) and 2.8 µl mutant co-CRISPR crRNA (0.4 µg µl−1 stock). The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 15 min to allow ribonucleoprotein complex formation. If a PCR repair template was used, it was melted during this step. Following ribonucleoprotein formation, 2 µl of mutant repair oligonucleotide (100 µM stock) and 2 µl of co-CRISPR repair oligonucleotide were added. Nuclease-free water was added to bring the final volume to 20 µl.

Microinjection and recovery

Young adult worms (either N2 or unc-13(nu641)) were immobilized on 2% agarose pads in halocarbon oil. The CRISPR–Cas9 injection mix was manually injected into the gonads of P0 worms using a Picospritzer III microinjector (Parker). The worm gonad was visualized using an Olympus IX51 inverted microscope with a ×40 air objective. Injected worms were recovered on seeded nematode growth medium plates at 20 °C for 3–4 days.

Screening for edited worms

F1 progeny expressing the co-injection marker (unc-58) were selected for screening and grown to the young adult stage. Genomic DNA was extracted from worm lysates, and the targeted locus was amplified by PCR. PCR products were digested with the engineered restriction site to identify potential edits. Worms containing the restriction site and lacking the unc-58 gain-of-function phenotype were singled out, and homozygous progeny were isolated. Genomic DNA was then re-extracted and sequenced using nanopore sequencing (Plasmidsaurus) to confirm the presence of the desired edits. Animals were then outcrossed at least four times with the parent strain. Sequence information for C. elegans strains can be found in Supplementary Note 1.

Aldicarb assay

To measure aldicarb sensitivity in C. elegans, 20–25 animals were placed on OP50-seeded agar plates containing 1 mM aldicarb (CarboSynth) as described previously87,88. Animals were scored for paralysis every 10 min for 2 h for each genotype. During an assay, the experimenter was blind to all genotypes, and each genotype was assayed at least ten times. Paralysis curves for each genotype were generated by averaging individual time courses.

Molecular model building and molecular dynamics simulations

A model of UNC13A consisting of the C1, C2B and MUN domains (residues 505–985) was predicted with AlphaFold (v.2.0; 01-JUL-21)89 using the UniProt sequence Q9UPW8 as input. The resulting model showed, as expected, a high similarity (root mean squared deviation, 1.08 Å) to the known 3D structure of rat MUNC-13 (PDB 5UE8)90. In addition to the protein, the two Zn2+ ions in the C1 domain were included. The Zn2+-coordinating cysteines and histidines were modeled as unprotonated and protonated on their Nε, respectively. All other amino acids were protonated at pH 7.0. Single mutations in the loop region (G808C, G808D, K811E, P814L), adjacent to the loop R799Q, and at the C1 domain (C587F, H554K) were incorporated with PyMol. Subsequently, WT UNC13A and all single mutants were solvated in cubic boxes of SPC/E water91 with the dimension of approximately 12.8 nm3. The net charges of the models were neutralized with K+Cl−, and an ionic strength of 150 mM K+Cl− was added. Additionally, five Ca2+ ions were inserted, replacing water molecules. To prevent ion aggregation, a previously published parameter set92 was applied. The protein was described by the Amber99SB*-ILDN force field93.

The subsequent molecular dynamics simulations were performed with the Gromacs 2021.2 package. After energy minimization and thermal equilibration with gradually decreasing position restraints, all periodic models were allowed to move freely during the following 1 µs-long production runs. To ensure reasonable statistics, all simulations were repeated five times. The temperature was maintained at 300 K and the pressure at 1 atm with the V-rescale scheme94 and the Parrinello-Rahman barostat95, respectively.

Constraining all bonds containing hydrogen atoms with the Lincs algorithm96 allowed a time step of 2 fs. Short-range electrostatics and van der Waals interactions were truncated at 1.2 nm, while long-range electrostatics were calculated with the Particle Ewald summation97.

Analysis

Images of 3D structures were generated with VMD98, graphs were drawn with the Matplotlib library included in Python99, and dipole moments were calculated with the MDAnalysis tool100.

Protein stability assay

HEK293T cells were transfected with a plasmid encoding WT GFP–P2A–FLAG–MUNC13-1 without or with disease-related variants. As a negative control, non-transfected cells were used. Cells were transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (according to the manufacturer’s manual) and 1 µg of the plasmid. Then, 24 h after transfection, cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1% IGEPAL CA 630, 1% sodium-deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS and 30 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.4, supplemented with aprotinin, leupeptin and phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). Lysates were sonicated and centrifuged at 4 °C for 15 min at 21,000g. Supernatants were transferred into a fresh tube, and protein concentration was determined. Samples were diluted in Laemmli buffer and incubated for 5 min at 95 °C. Next, 10 μg of the samples were separated on 8% Bis–Tris gel in cold MOPS buffer at 150 V, blotted on a nitrocellulose membrane (Protran 0.2 NC, Amersham) and stained with the Pierce reversible protein stain and destain kit (according to the manufacturer’s manual; Thermo Fisher Scientific, 46430) for a sample loading control. The membranes were cut and incubated with an anti-Flag antibody, anti-GFP antibody (see Supplementary Table 2) and corresponding secondary antibodies, and the chemiluminescence signal was detected on an ECL ChemoStar imager (Intas). Signal intensity quantification was done in Fiji101. Protein levels were first normalized to the total protein staining of the corresponding lane, and ratios between the GFP and Flag signals were calculated.

Statistics

Electrophysiological data are presented as means ± s.e.m., and statistical significance was determined using the non-parametric two-tailed Mann–Whitney test. For the C. elegans paralysis assay, data were analyzed using a non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s test for all pairwise comparisons. Western blots and imaging data are presented as means ± s.e.m., and statistical significance was evaluated using a non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test. All analyses used two-sided tests and were performed using R statistical software (v.4.4.2)102 and the R packages ‘coin’ and ‘dunn.test’.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper, Supplementary Data 1–3, the Source Data file and in the Supplemental Information file. Molecular dynamics simulation data are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14554776 (ref. 103). All other primary data will be made available on request from the corresponding authors. Publicly available databases used in this study include GeneMatcher (https://genematcher.org), MetaDome web server (https://stuart.radboundumc.nl/metadome/), ClinVAR (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar), Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD; http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org), OMIM (http://www.omim.org), UCSC Genome Browser (https://genome.ucsc.edu), Ensembl (https://www.ensembl.org) and UniProt (https://www.uniprot.org). Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

No code was developed for this study.

References

Ma, C., Su, L., Seven, A. B., Xu, Y. & Rizo, J. Reconstitution of the vital functions of Munc18 and Munc13 in neurotransmitter release. Science 339, 421–425 (2013).

Lai, Y. et al. Molecular mechanisms of synaptic vesicle priming by Munc13 and Munc18. Neuron 95, 591–607.e10 (2017).

Brunger, A. T., Choi, U. B., Lai, Y., Leitz, J. & Zhou, Q. Molecular mechanisms of fast neurotransmitter release. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 47, 469–497 (2018).

Imig, C. et al. The morphological and molecular nature of synaptic vesicle priming at presynaptic active zones. Neuron 84, 416–431 (2014).

Siksou, L. et al. A common molecular basis for membrane docking and functional priming of synaptic vesicles. Eur. J. Neurosci. 30, 49–56 (2009).

Rosenmund, C. & Stevens, C. F. Definition of the readily releasable pool of vesicles at hippocampal synapses. Neuron 16, 1197–1207 (1996).

Sakamoto, H. et al. Synaptic weight set by Munc13-1 supramolecular assemblies. Nat. Neurosci. 21, 41–49 (2018).

Bohme, M. A. et al. Rapid active zone remodeling consolidates presynaptic potentiation. Nat. Commun. 10, 1085 (2019).

Fukaya, R. et al. Increased vesicle fusion competence underlies long-term potentiation at hippocampal mossy fiber synapses. Sci. Adv. 9, eadd3616 (2023).

Junge, H. J. et al. Calmodulin and Munc13 form a Ca2+ sensor/effector complex that controls short-term synaptic plasticity. Cell 118, 389–401 (2004).

Shin, O. H. et al. Munc13 C2B domain is an activity-dependent Ca2+ regulator of synaptic exocytosis. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17, 280–288 (2010).

Lipstein, N. et al. Munc13-1 is a Ca2+-phospholipid-dependent vesicle priming hub that shapes synaptic short-term plasticity and enables sustained neurotransmission. Neuron 109, 3980–4000.e7 (2021).

Lipstein, N. et al. Dynamic control of synaptic vesicle replenishment and short-term plasticity by Ca2+-calmodulin-Munc13-1 signaling. Neuron 79, 82–96 (2013).

Betz, A. et al. Munc13-1 is a presynaptic phorbol ester receptor that enhances neurotransmitter release. Neuron 21, 123–136 (1998).

Rhee, J. S. et al. Beta phorbol ester- and diacylglycerol-induced augmentation of transmitter release is mediated by Munc13s and not by PKCs. Cell 108, 121–133 (2002).

Rosenmund, C. et al. Differential control of vesicle priming and short-term plasticity by Munc13 isoforms. Neuron 33, 411–424 (2002).

Augustin, I., Betz, A., Herrmann, C., Jo, T. & Brose, N. Differential expression of two novel Munc13 proteins in rat brain. Biochem. J. 337, 363–371 (1999).

Koch, H., Hofmann, K. & Brose, N. Definition of Munc13-homology-domains and characterization of a novel ubiquitously expressed Munc13 isoform. Biochem. J. 349, 247–253 (2000).

Augustin, I., Rosenmund, C., Sudhof, T. C. & Brose, N. Munc13-1 is essential for fusion competence of glutamatergic synaptic vesicles. Nature 400, 457–461 (1999).

Varoqueaux, F. et al. Total arrest of spontaneous and evoked synaptic transmission but normal synaptogenesis in the absence of Munc13-mediated vesicle priming. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 9037–9042 (2002).

Sigler, A. et al. Formation and maintenance of functional spines in the absence of presynaptic glutamate release. Neuron 94, 304–311.e4 (2017).

Mullins, J. R., McFadden, K., Snow, N. & Oviedo, A. Homozygous UNC13A variant in an infant with congenital encephalopathy and severe neuromuscular phenotype: a case report with detailed central nervous system neuropathologic findings. Cureus 14, e30774 (2022).

Engel, A. G., Selcen, D., Shen, X. M., Milone, M. & Harper, C. M. Loss of MUNC13-1 function causes microcephaly, cortical hyperexcitability, and fatal myasthenia. Neurol. Genet. 2, e105 (2016).

Lipstein, N. et al. Synaptic UNC13A protein variant causes increased neurotransmission and dyskinetic movement disorder. J. Clin. Invest. 127, 1005–1018 (2017).

Diekstra, F. P. et al. C9orf72 and UNC13A are shared risk loci for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia: a genome-wide meta-analysis. Ann. Neurol. 76, 120–133 (2014).

Diekstra, F. P. et al. UNC13A is a modifier of survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiol. Aging 33, 630.e3–630.e8 (2012).

van Es, M. A. et al. Genome-wide association study identifies 19p13.3 (UNC13A) and 9p21.2 as susceptibility loci for sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat. Genet. 41, 1083–1087 (2009).

Daoud, H. et al. Analysis of the UNC13A gene as a risk factor for sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch. Neurol. 67, 516–517 (2010).

Chio, A. et al. UNC13A influences survival in Italian amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients: a population-based study. Neurobiol. Aging 34, 357.e1–357.e5 (2013).

Vidal-Taboada, J. M. et al. UNC13A confers risk for sporadic ALS and influences survival in a Spanish cohort. J. Neurol. 262, 2285–2292 (2015).

Gaastra, B. et al. Rare genetic variation in UNC13A may modify survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Frontotemporal Degener. 17, 593–599 (2016).

Placek, K. et al. UNC13A polymorphism contributes to frontotemporal disease in sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiol. Aging 73, 190–199 (2019).

Willemse, S. W. et al. UNC13A in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: from genetic association to therapeutic target. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 94, 649–656 (2023).

Brown, A. L. et al. TDP-43 loss and ALS-risk SNPs drive mis-splicing and depletion of UNC13A. Nature 603, 131–137 (2022).

Ma, X. R. et al. TDP-43 represses cryptic exon inclusion in the FTD-ALS gene UNC13A. Nature 603, 124–130 (2022).

Akiyama, T., Koike, Y., Petrucelli, L. & Gitler, A. D. Cracking the cryptic code in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia: towards therapeutic targets and biomarkers. Clin. Transl. Med. 12, e818 (2022).

Wiel, L. et al. MetaDome: pathogenicity analysis of genetic variants through aggregation of homologous human protein domains. Hum. Mutat. 40, 1030–1038 (2019).

Cheng, J. et al. Accurate proteome-wide missense variant effect prediction with AlphaMissense. Science 381, eadg7492 (2023).

Betz, A., Okamoto, M., Benseler, F. & Brose, N. Direct interaction of the rat unc-13 homologue Munc13-1 with the N terminus of syntaxin. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 2520–2526 (1997).

Basu, J. et al. A minimal domain responsible for Munc13 activity. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 1017–1018 (2005).

Marin, O. Developmental timing and critical windows for the treatment of psychiatric disorders. Nat. Med. 22, 1229–1238 (2016).

Bekkers, J. M. & Stevens, C. F. Excitatory and inhibitory autaptic currents in isolated hippocampal neurons maintained in cell culture. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 88, 7834–7838 (1991).

Furshpan, E. J., MacLeish, P. R., O’Lague, P. H. & Potter, D. D. Chemical transmission between rat sympathetic neurons and cardiac myocytes developing in microcultures: evidence for cholinergic, adrenergic, and dual-function neurons. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 73, 4225–4229 (1976).

Stewart, S. A. et al. Lentivirus-delivered stable gene silencing by RNAi in primary cells. RNA 9, 493–501 (2003).

Dulubova, I. et al. A Munc13/RIM/Rab3 tripartite complex: From priming to plasticity? EMBO J. 24, 2839–2850 (2005).

Camacho, M. et al. Heterodimerization of Munc13 C2A domain with RIM regulates synaptic vesicle docking and priming. Nat. Commun. 8, 15293 (2017).

Deng, L., Kaeser, P. S., Xu, W. & Sudhof, T. C. RIM proteins activate vesicle priming by reversing autoinhibitory homodimerization of Munc13. Neuron 69, 317–331 (2011).

Betz, A. et al. Functional interaction of the active zone proteins Munc13-1 and RIM1 in synaptic vesicle priming. Neuron 30, 183–196 (2001).

Basu, J., Betz, A., Brose, N. & Rosenmund, C. Munc13-1 C1 domain activation lowers the energy barrier for synaptic vesicle fusion. J. Neurosci. 27, 1200–1210 (2007).

Lin, K. H., Taschenberger, H. & Neher, E. A sequential two-step priming scheme reproduces diversity in synaptic strength and short-term plasticity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2207987119 (2022).

Richmond, J. E., Davis, W. S. & Jorgensen, E. M. UNC-13 is required for synaptic vesicle fusion in C. elegans. Nat. Neurosci. 2, 959–964 (1999).

Richmond, J. E., Weimer, R. M. & Jorgensen, E. M. An open form of syntaxin bypasses the requirement for UNC-13 in vesicle priming. Nature 412, 338–341 (2001).

Michelassi, F., Liu, H., Hu, Z. & Dittman, J. S. A C1–C2 module in Munc13 inhibits calcium-dependent neurotransmitter release. Neuron 95, 577–590.e5 (2017).

Liu, H. et al. Heterodimerization of UNC-13/RIM regulates synaptic vesicle release probability but not priming in C. elegans. eLife 8, e40585 (2019).

Quest, A. F., Bardes, E. S. & Bell, R. M. A phorbol ester binding domain of protein kinase C gamma. High affinity binding to a glutathione-S-transferase/Cys2 fusion protein. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 2953–2960 (1994).

Malenka, R. C., Ayoub, G. S. & Nicoll, R. A. Phorbol esters enhance transmitter release in rat hippocampal slices. Brain Res. 403, 198–203 (1987).

Zucker, R. S. & Regehr, W. G. Short-term synaptic plasticity. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 64, 355–405 (2002).

Wesseling, J. F. & Lo, D. C. Limit on the role of activity in controlling the release-ready supply of synaptic vesicles. J. Neurosci. 22, 9708–9720 (2002).

Xian, J. et al. Assessing the landscape of STXBP1-related disorders in 534 individuals. Brain 145, 1668–1683 (2022).

Lopez-Rivera, J. A. et al. A catalogue of new incidence estimates of monogenic neurodevelopmental disorders caused by de novo variants. Brain 143, 1099–1105 (2020).

Ma, C., Li, W., Xu, Y. & Rizo, J. Munc13 mediates the transition from the closed syntaxin–Munc18 complex to the SNARE complex. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 18, 542–549 (2011).

He, E. et al. Munc13-1 and Munc18-1 together prevent NSF-dependent de-priming of synaptic vesicles. Nat. Commun. 8, 15915 (2017).

Meijer, M. et al. Munc18-1 mutations that strongly impair SNARE-complex binding support normal synaptic transmission. EMBO J. 31, 2156–2168 (2012).

Li, L. et al. A hyperactive form of unc-13 enhances Ca2+ sensitivity and synaptic vesicle release probability in C. elegans. Cell Rep. 28, 2979–2995.e4 (2019).

Lipstein, N. et al. Nonconserved Ca2+/calmodulin binding sites in Munc13s differentially control synaptic short-term plasticity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 32, 4628–4641 (2012).

Kawabe, H. et al. ELKS1 localizes the synaptic vesicle priming protein bMunc13-2 to a specific subset of active zones. J. Cell Biol. 216, 1143–1161 (2017).

Bohme, M. A. et al. Active zone scaffolds differentially accumulate Unc13 isoforms to tune Ca2+ channel-vesicle coupling. Nat. Neurosci. 19, 1311–1320 (2016).

Ling, J. P., Pletnikova, O., Troncoso, J. C. & Wong, P. C. TDP-43 repression of nonconserved cryptic exons is compromised in ALS-FTD. Science 349, 650–655 (2015).

Neumann, M. et al. Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science 314, 130–133 (2006).

Zarebidaki, F. et al. Disentangling the roles of RIM and Munc13 in synaptic vesicle localization and neurotransmission. J. Neurosci. 40, 9372–9385 (2020).

Bennett, C. F., Krainer, A. R. & Cleveland, D. W. Antisense oligonucleotide therapies for neurodegenerative diseases. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 42, 385–406 (2019).

Lu, J. et al. Structural basis for a Munc13-1 homodimer to Munc13-1/RIM heterodimer switch. PLoS Biol. 4, e192 (2006).

Sobreira, N., Schiettecatte, F., Valle, D. & Hamosh, A. GeneMatcher: a matching tool for connecting investigators with an interest in the same gene. Hum. Mutat. 36, 928–930 (2015).

Lionel, A. C. et al. Improved diagnostic yield compared with targeted gene sequencing panels suggests a role for whole-genome sequencing as a first-tier genetic test. Genet. Med. 20, 435–443 (2018).

Monies, D. et al. Lessons learned from large-scale, first-tier clinical exome sequencing in a highly consanguineous population. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 104, 1182–1201 (2019).

Boonsawat, P. et al. Elucidation of the phenotypic spectrum and genetic landscape in primary and secondary microcephaly. Genet. Med. 21, 2043–2058 (2019).

Freeman, P. J. et al. Standardizing variant naming in literature with VariantValidator to increase diagnostic rates. Nat. Genet. 56, 2284–2286 (2024).

Callebaut, I. et al. Comprehensive functional annotation of 18 missense mutations found in suspected hemochromatosis type 4 patients. Hum. Mol. Genet. 23, 4479–4490 (2014).

Raud, L. et al. Functional analysis of novel RHD variants: splicing disruption is likely to be a common mechanism of variant D phenotype. Transfusion 59, 1367–1375 (2019).

Brose, N., Hofmann, K., Hata, Y. & Sudhof, T. C. Mammalian homologues of Caenorhabditis elegans unc-13 gene define novel family of C2-domain proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 25273–25280 (1995).

Lois, C., Hong, E. J., Pease, S., Brown, E. J. & Baltimore, D. Germline transmission and tissue-specific expression of transgenes delivered by lentiviral vectors. Science 295, 868–872 (2002).

Camacho, M. et al. Control of neurotransmitter release by two distinct membrane-binding faces of the Munc13-1 C1C2B region. eLife 10, e72030 (2021).

Burgalossi, A. et al. Analysis of neurotransmitter release mechanisms by photolysis of caged Ca2+ in an autaptic neuron culture system. Nat. Protoc. 7, 1351–1365 (2012).

Rueden, C. T. et al. ImageJ2: ImageJ for the next generation of scientific image data. BMC Bioinformatics 18, 529 (2017).

Brenner, S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77, 71–94 (1974).

Padmanarayana, M. et al. A unique C2 domain at the C terminus of Munc13 promotes synaptic vesicle priming. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2016276118 (2021).

Dittman, J. S. & Kaplan, J. M. Behavioral impact of neurotransmitter-activated G-protein-coupled receptors: muscarinic and GABAB receptors regulate Caenorhabditis elegans locomotion. J. Neurosci. 28, 7104–7112 (2008).

Nurrish, S., Segalat, L. & Kaplan, J. M. Serotonin inhibition of synaptic transmission: Gαo decreases the abundance of UNC-13 at release sites. Neuron 24, 231–242 (1999).

Jumper, J. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589 (2021).

Xu, J. et al. Mechanistic insights into neurotransmitter release and presynaptic plasticity from the crystal structure of Munc13-1 C1C2BMUN. eLife 6, e22567 (2017).

Berendsen, H. J. C., Grigera, J. R. & Straatsma, T. P. The missing term in effective pair potentials. J. Phys. Chem. 91, 6269–6271 (1987).

Joung, I. S. & Cheatham, T. E. III. Determination of alkali and halide monovalent ion parameters for use in explicitly solvated biomolecular simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 112, 9020–9041 (2008).

Lindorff-Larsen, K. et al. Improved side-chain torsion potentials for the Amber ff99SB protein force field. Proteins 78, 1950–1958 (2010).

Bussi, G., Donadio, D. & Parrinello, M. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J. Chem. Phys. 126, 014101 (2007).

Parrinello, M. & Rahman, A. Polymorphic transitions in single crystals: a new molecular dynamics method. J. Appl. Phys. 52, 7182–7190 (1981).

Hess, B., Bekker, H., Berendsen, H. J. C. & Fraaije, J. G. E. M. LINCS: a linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 18, 1463–1472 (1997).

Darden, T., York, D. & Pedersen, L. Particle mesh Ewald: an N⋅log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 10089–10092 (1993).

Humphrey, W., Dalke, A. & Schulten, K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph 14, 33–38 (1996).

Hunter, J. D. Matplotlib: a 2D graphics environment. Comput. Sci. Eng 9, 90–95 (2007).