Abstract

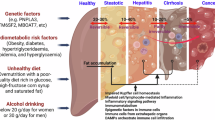

Immune cells play a central yet poorly understood role in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASLD/MASH), a global cause of liver disease with limited treatment. Limited access to human livers and lack of studies across MASLD/MASH stages thwart identification of stage-specific immunological targets. Here we provide a unique single-cell RNA sequencing atlas of paired peripheral blood and liver fine-needle aspirates from a full-spectrum MASLD/MASH human cohort. Our findings included heightened immunoregulatory programs with MASH progression, such as enriched hepatic regulatory T cells, monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells, TREM2+S100A9+ macrophages and S100hiHLAlo type 2 conventional dendritic cells. Hepatic cytotoxic T cell functions increased with inflammation, but decreased with fibrosis, while acquiring an exhausted signature, whereas natural killer cell-driven toxicity intensified. Our dataset proposes immunological mechanisms for increased fibrogenesis and vulnerability to liver cancer and infections in MASH and provides a basis for a deeper understanding of human immunological dysfunction in chronic liver disease and a roadmap to new targeted therapies.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The human RNA-seq data are deposited in the NIH dbGaP portal (accession no. phs004044) and can be used only for studying health, medical or biomedical conditions. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Younossi, Z. M. et al. The global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH): a systematic review. Hepatology 77, 1335–1347 (2023).

Taylor, R. S. et al. Association between fibrosis stage and outcomes of patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 158, 1611–1625.e12 (2020).

Lazarus, J. V. et al. Opportunities and challenges following approval of resmetirom for MASH liver disease. Nat. Med. 30, 3402–3405 (2024).

Huby, T. & Gautier, E. L. Immune cell-mediated features of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 22, 429–443 (2022).

Guilliams, M. et al. Spatial proteogenomics reveals distinct and evolutionarily conserved hepatic macrophage niches. Cell 185, 379–396.e38 (2022).

Mueller, J. L. et al. Circulating soluble CD163 is associated with steatohepatitis and advanced fibrosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 6, e114 (2015).

Lidofsky, A. et al. Macrophage activation marker soluble CD163 is a dynamic marker of liver fibrogenesis in human immunodeficiency virus/hepatitis C virus coinfection. J. Infect. Dis. 218, 1394–1403 (2018).

Cui, A. et al. Single-cell atlas of the liver myeloid compartment before and after cure of chronic viral hepatitis. J. Hepatol. 80, 251–267 (2024).

Racanelli, V. & Rehermann, B. The liver as an immunological organ. Hepatology 43, S54–S62 (2006).

Canton, M. et al. Reactive oxygen species in macrophages: sources and targets. Front. Immunol. 12, 734229 (2021).

Katze, M. G., He, Y. & Gale, M. Viruses and interferon: a fight for supremacy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2, 675–687 (2002).

Mohlenberg, M. et al. The role of IFN in the development of NAFLD and NASH. Cytokine 124, 154519 (2019).

Lou, Y. et al. Essential roles of S100A10 in Toll-like receptor signaling and immunity to infection. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 17, 1053–1062 (2020).

Ray, A., Chakraborty, K. & Ray, P. Immunosuppressive MDSCs induced by TLR signaling during infection and role in resolution of inflammation. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 3, 52 (2013).

Mastio, J. et al. Identification of monocyte-like precursors of granulocytes in cancer as a mechanism for accumulation of PMN-MDSCs. J. Exp. Med. 216, 2150–2169 (2019).

Bekaert, M., Verhelst, X., Geerts, A., Lapauw, B. & Calders, P. Association of recently described adipokines with liver histology in biopsy-proven non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review. Obes. Rev. 17, 68–80 (2016).

Krautbauer, S. et al. Chemerin is highly expressed in hepatocytes and is induced in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis liver. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 95, 199–205 (2013).

Street, K. et al. Slingshot: cell lineage and pseudotime inference for single-cell transcriptomics. BMC Genom. 19, 477 (2018).

Kwak, T. et al. Distinct populations of immune-suppressive macrophages differentiate from monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer. Cell Rep. 33, 108571 (2020).

La Manno, G. et al. RNA velocity of single cells. Nature 560, 494–498 (2018).

Seidman, J. S. et al. Niche-specific reprogramming of epigenetic landscapes drives myeloid cell diversity in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Immunity 52, 1057–1074.e7 (2020).

Barbosa, C. M. V., Bincoletto, C., Barros, C. C., Ferreira, A. T. & Paredes-Gamero, E. J. PLCγ2 and PKC are important to myeloid lineage commitment triggered by M-SCF and G-CSF. J. Cell. Biochem. 115, 42–51 (2014).

Hollmén, M. et al. G-CSF regulates macrophage phenotype and associates with poor overall survival in human triple-negative breast cancer. Oncoimmunology 5, e1115177 (2016).

Ganguly, S. et al. Lipid-associated macrophages’ promotion of fibrosis resolution during MASH regression requires TREM2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2405746121 (2024).

Xu, R. et al. Lipid-associated macrophages between aggravation and alleviation of metabolic diseases. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 35, 981–995 (2024).

Wei, G. et al. Comparison of murine steatohepatitis models identifies a dietary intervention with robust fibrosis, ductular reaction, and rapid progression to cirrhosis and cancer. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 318, G174–G188 (2020).

Jahrsdörfer, B. et al. Granzyme B produced by human plasmacytoid dendritic cells suppresses T-cell expansion. Blood 115, 1156–1165 (2010).

Heger, L. et al. XCR1 expression distinguishes human conventional dendritic cell type 1 with full effector functions from their immediate precursors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2300343120 (2023).

Averill, M. M. et al. S100A9 differentially modifies phenotypic states of neutrophils, macrophages, and dendritic cells. Circulation 123, 1216–1226 (2011).

Plebanek, M. P. et al. A lactate-SREBP2 signaling axis drives tolerogenic dendritic cell maturation and promotes cancer progression. Sci. Immunol. 9, eadi4191 (2024).

Haas, J. T. et al. Transcriptional network analysis implicates altered hepatic immune function in NASH development and resolution. Nat. Metab. 1, 604–614 (2019).

Rau, M. et al. Progression from nonalcoholic fatty liver to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is marked by a higher frequency of Th17 cells in the liver and an increased Th17/resting regulatory T cell ratio in peripheral blood and in the liver. J. Immunol. 196, 97–105 (2016).

Woestemeier, A. et al. Multicytokine-producing CD4+ T cells characterize the livers of patients with NASH. JCI Insight 8, e15381 (2023).

Dudek, M. et al. Auto-aggressive CXCR6+ CD8 T cells cause liver immune pathology in NASH. Nature 592, 444–449 (2021).

Pfister, D. et al. NASH limits anti-tumour surveillance in immunotherapy-treated HCC. Nature 592, 450–456 (2021).

Yasumizu, Y. et al. Single-cell transcriptome landscape of circulating CD4+ T cell populations in autoimmune diseases. Cell Genom. 4, 100473 (2024).

Stewart, A. et al. Single-cell transcriptomic analyses define distinct peripheral B cell subsets and discrete development pathways. Front. Immunol. 12, 602539 (2021).

Hikida, M., Johmura, S., Hashimoto, A., Takezaki, M. & Kurosaki, T. Coupling between B cell receptor and phospholipase C-gamma2 is essential for mature B cell development. J. Exp. Med. 198, 581–589 (2003).

Svensson, A., Patzi Churqui, M., Schlüter, K., Lind, L. & Eriksson, K. Maturation-dependent expression of AIM2 in human B-cells. PLoS ONE 12, e0183268 (2017).

Li, H., Borrego, F., Nagata, S. & Tolnay, M. Fc receptor-like 5 expression distinguishes two distinct subsets of human circulating tissue-like memory B cells. J. Immunol. 196, 4064–4074 (2016).

Andreani, V., Ramamoorthy, S., Fässler, R. & Grosschedl, R. Integrin β1 regulates marginal zone B cell differentiation and PI3K signaling. J. Exp. Med. 220, e20220342 (2023).

Maleki, I. et al. Serum immunoglobulin A concentration is a reliable biomarker for liver fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 20, 12566–12573 (2014).

De Roza, M. A. et al. Immunoglobulin G in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis predicts clinical outcome: A prospective multi-centre cohort study. World J. Gastroenterol. 27, 7563–7571 (2021).

Chen, Y. et al. The potential role of CMC1 as an immunometabolic checkpoint in T cell immunity. Oncoimmunology 13, 2344905 (2024).

Castriconi, R. et al. Molecular mechanisms directing migration and retention of natural killer cells in human tissues. Front. Immunol. 9, 2324 (2018).

Jin, S., Plikus, M. V. & Nie, Q. CellChat for systematic analysis of cell-cell communication from single-cell transcriptomics. Nat. Protoc. 20, 180–219 (2025).

Jiang, Y. & Lu, L. New insight into the agonism of protease-activated receptors as an immunotherapeutic strategy. J. Biol. Chem. 300, 105614 (2024).

Radaeva, S. et al. Natural killer cells ameliorate liver fibrosis by killing activated stellate cells in NKG2D-dependent and tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-dependent manners. Gastroenterology 130, 435–452 (2006).

Seitz, T. et al. Fibroblast growth factor 9 is expressed by activated hepatic stellate cells and promotes progression of hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 10, 4546 (2020).

Zhou, L. et al. Integrated analysis highlights the immunosuppressive role of TREM2+ macrophages in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front. Immunol. 13, 848367 (2022).

Ahmad, J. N. et al. Bordetella adenylate cyclase toxin inhibits monocyte-to-macrophage transition and dedifferentiates human alveolar macrophages into monocyte-like cells. mBio 10, e01743-19 (2019).

Wahlang, B., McClain, C., Barve, S. & Gobejishvili, L. Role of cAMP and phosphodiesterase signaling in liver health and disease. Cell. Signal. 49, 105–115 (2018).

Deczkowska, A. et al. XCR1+ type 1 conventional dendritic cells drive liver pathology in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Nat. Med. 27, 1043–1054 (2021).

Wimmers, F. et al. Single-cell analysis reveals that stochasticity and paracrine signaling control interferon-alpha production by plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Nat. Commun. 9, 3317 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Akoya scientist, A. Gad, for his valuable input with the Opal 3-plex tissue immunostaining used for validation. We thank Z. Li for helping organize the raw sequencing data for database deposition. This work was financially supported by Bristol Myers Squibb and grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) (grant nos. R01DK098079 to R.T.C. and R56DK134251 to N.A. and R.T.C.). The content of this work, however, is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the sponsors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: R.T.C. and N.A. Methodology: C.O., M.S.W., H.B.P., O.P.M., L.P.W., P.H., U.K., Y.V.P., R.I.S. and N.A. Software and formal analysis: O.P.M., M.S.W. and C.O. Investigation: O.P.M., M.S.W., C.O., H.B.P., R.I.S., R.T.C. and N.A. Resources: M.D.B., J.E., C.C., S. Salloum, Z.R., A.O., S. Shroff, K.E.C. and E.D.C. Writing—original draft: M.S.W., O.P.M., C.O. and N.A. Writing—review and editing: O.P.M., M.S.W., E.D.C., R.T.C., R.I.S. and N.A. Funding acquisition: R.T.C. and N.A. Supervision: N.A.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

E.D.C. was formerly employed by Bristol Myers Squibb. R.T.C. received research grants to the institution from Abbvie, Gilead Sciences, Merck, Boehringer, Janssen and BMS. N.A. received a research grant to the institution from Boehringer for unrelated work. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Immunology thanks Haydn Kissick and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available. Primary Handling Editor: Ioana Staicu, in collaboration with the Nature Immunology team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Serum levels of monocyte and macrophage activation marker, soluble (s)CD163.

Levels of sCD163 significantly correlated with (a) non-invasive markers of fibrosis, liver stiffness (kPa) and APRI score; and (b) liver injury enzymes, ALT and AST, two-sided Spearman correlation. (c) Levels of sCD163 were significantly higher in patients with histologically defined MASH, compared to healthy controls (n = 10), and in advanced MASH (n = 9), compared to NS-SS (n = 6); and (d) in patients with high NAS score (>4, n = 11) compared to low NAS score (<5, n = 14) (the box plots represent the median and interquartile ranges, and the whiskers depict the minimum and maximum of the data set), two-sided Mann–Whitney unpaired U test. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001. Abbreviations: kPa, kilopascal; APRI, aspartate aminotransferase–to-platelet ratio index; ALT, Alanine aminotransferase; AST, Aspartate aminotransferase; NAS; MASLD (former NAFLD) activity score. NS, no steatosis/inflammation/fibrosis.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Additional information on the quality of scRNA-seq dataset.

(a) Ridge plot of the housekeeping gene B2M expression per sample, per compartment. (b) Stacked bar chart of sample proportion in each cell type, per compartment. (c) Separate clustering UMAPs for liver FNAs (n = 55,234) and PBMCs (n = 123,753), color-coded by cell type (clustering settings: 20 PCs, Louvain Resolution=0.05).

Extended Data Fig. 3 Broad characterization of cell type enrichment per compartment and per liver disease stage.

(a) Box plots showing per-sample (n = 25) frequencies of CD16− NK cells, MAIT cells, CD8+ T cells and B cells, and the ratio of CD4+/CD8+ T cells, per compartment: data are presented as median values (horizontal line), 25th/75th quartile values (bounds of boxes), and non-outlier minimum/maximum (whiskers); two-sided Wilcoxon. (b) Box plot of the proportion of each cell type as a percentage of each sample in FNA (left) and PBMC (right): data are presented as median values (horizontal line), 25th/75th quartile values (bounds of boxes), and non-outlier minimum/maximum (whiskers); NS-SS (n = 6), early MASH (n = 10), advanced MASH (n = 9); two-sided permutation test; significance (*) determined by false-discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05 and log2 false discovery (log2FD)>0.58. (c) Scatter plot of average pathway enrichment score per patient (n = 25) of (left) ROS/RNS production in macrophages by controlled attenuation parameter (CAP reflects steatosis), (middle) collagen formation in hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) by MASLD/NAFLD activity score (NAS), and (right) insulin-growth factor binding protein (IGF) and IGF-binding protein (IGFBP) in hepatocytes by liver enzyme ALT: error bands represent 95% confidence interval; two-sided Pearson.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Interferon-induced protein validation and liver sources of interferons.

Box plot by cell type per patient of average (a) ISG score per disease stage (NS-SS (n = 6), early MASH (n = 10), advanced MASH (n = 9)) in liver FNA (left) and PBMCs (right), (b) IFNG expression in liver FNAs (n = 25), and (c) upstream gene expression for interferon-alpha (left) and interferon-beta (right) in liver FNAs (n = 25): data are presented as median values (horizontal line), 25th/75th quartile values (bounds of boxes), and non-outlier minimum/maximum (whiskers); two-sided Wilcoxon; upstream genes are shown in Extended Data Table 2. (d) Magnification of Extended Data Fig. 3a: box plot of the percentage of pDCs out of each sample in FNA (left) and PBMC (right): data presented as in 5a; two-sided permutation test; significance (*) determined by false-discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05 and log2 false discovery (log2FD)>0.58. (e) Comparative ISG expression in liver monocytes (left) and macrophages (right) between patients without steatosis or with steatosis (NS-SS), those with MASH and those with untreated HCV: data are presented as median values (horizontal line); two-sided Wilcoxon; ***P < .001. (f) Immuno-fluorescent (IF) validation of MX1 and IFIT3 in macrophages in human liver tissue biopsies. Representative image merged and per channel (left) and expression fractions of MX1 + , IFIT3 + , and MX1 + IFIT3+ out of macrophages (CD68 + ) for three disease stages (right): simple steatosis (SS, n = 1), early MASH (F1, n = 1), and advanced MASH (F2, n = 1).

Extended Data Fig. 5 Additional data on monocyte association with MASLD/MASH progression.

(a) Monocyte chemotaxis receptors: box plots of average CCRL2 (left) and CMKLR1 (right) expression in FNA by patient: data are presented as median values (horizontal line), 25th/75th quartile values (bounds of boxes), and non-outlier minimum/maximum (whiskers); NS-SS (n = 6), early MASH (n = 10), advanced MASH (n = 9); two-sided Wilcoxon (b) Monocyte chemotaxis ligands: scatter plot of average RARRES2 expression in hepatocytes per patient (n = 25) by CAP score: error bands represent 95% confidence interval; two-sided Pearson.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Investigation of the monocyte and monocyte-derived cell paths without specifying a starting point of cell progression.

(a) Velocity analysis of monocyte and monocyte-derived cells (macrophages and cDCs) shown by UMAP in early MASH (left) and advanced MASH (right) and (b) unbiased pseudotime via slingshot analysis, color-coded per cell type.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Investigation of T-cell activation marker ICOS, its ligand, and B-cell light chain kappa versus lambda expression.

(a) Immunofluorescent staining of ICOS in human liver biopsies for three disease stages: simple steatosis (SS, steatosis grade 1, n = 1), early MASH (F1, steatosis grade 1, n = 1), and advanced MASH (F2, steatosis grade 2, n = 1). Box plots of (b) average ICOS expression by T-cell subpopulation per patient FNA (n = 25), (c) average Treg ICOS expression by histological steatosis grade per patient FNA (0-1: n = 10; 2: n = 11, 3 n = 3), two-sided Wilcoxon, and (d) average ICOSLG expression by cell type per patient FNA (n = 25): data are presented as median values (horizontal line), 25th/75th quartile values (bounds of boxes), and non-outlier minimum/maximum (whiskers). (e) Bar chart showing the fraction of B cells that express kappa (IGKC) or lambda (IGLC2-7) light chain genes for liver FNA (left) and PBMC (right).

Extended Data Fig. 8 Additional data on immune cell crosstalk.

Changes in predicted individual ligand-receptor interactions between (a) SS versus early MASH and (b) early versus advanced MASH, from HSCs to immune cells (left) and from immune cells to HSCs (right). (c) Radar plot of the total number of cell-cell interactions (both incoming and outgoing) between macrophages and other cell types (left) and between pDCs and other cell types (right).

Supplementary information

Source data

Source Data Fig. 3

Composite IF images for SS, MASH F1 and MASH F2 in Fig. 3h.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Martin, O.P., Wallace, M.S., Oetheimer, C. et al. Single-cell atlas of human liver and blood immune cells across fatty liver disease stages reveals distinct signatures linked to liver dysfunction and fibrogenesis. Nat Immunol 26, 1596–1611 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41590-025-02255-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41590-025-02255-y