Abstract

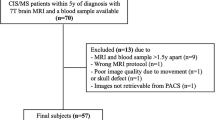

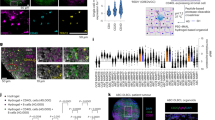

In multiple sclerosis (MS), B cell-rich tertiary lymphoid tissues (TLTs) in the brain leptomeninges associate with cortical gray matter injury. Using a model of Th17 cell-driven experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in mice, we found that inhibitors of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTKi) prevented TLT formation and cortical pathology in a B cell activating factor (BAFF)-dependent manner. BTKi reduced expression of lymphotoxin ligands, and cotreatment with a lymphotoxin-β receptor agonist abrogated the benefits of BTKi. TLT and cortical pathology tracked with a high CXCL13:BAFF ratio in the leptomeninges, which was reduced by BTKi. Moreover, we observed high CXCL13:BAFF ratios in post mortem cerebral spinal fluid from patients with MS and pathologically confirmed leptomeningeal inflammation, as well as in living patients with MS and radiologically confirmed paramagnetic rim lesions. In summary, using experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, we revealed a molecular circuit that leads to TLT formation and cortical injury with translational relevance for detection of this pathology in patients with MS.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Extended Data Information. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Aloisi, F. & Pujol-Borrell, R. Lymphoid neogenesis in chronic inflammatory diseases. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 6, 205–217 (2006).

Pikor, N. B. et al. Integration of Th17- and lymphotoxin-derived signals initiates meningeal-resident stromal cell remodeling to propagate neuroinflammation. Immunity 43, 1160–1173 (2015).

Serafini, B., Rosicarelli, B., Magliozzi, R., Stigliano, E. & Aloisi, F. Detection of ectopic B-cell follicles with germinal centers in the meninges of patients with secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Brain Pathol. 14, 164–174 (2004).

Bevan, R. J. et al. Meningeal inflammation and cortical demyelination in acute multiple sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 84, 829–842 (2018).

Howell, O. W. et al. Meningeal inflammation is widespread and linked to cortical pathology in multiple sclerosis. Brain 134, 2755–2771 (2011).

Magliozzi, R. et al. A gradient of neuronal loss and meningeal inflammation in multiple sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 68, 477–493 (2010).

Magliozzi, R. et al. B-cell enrichment and Epstein–Barr virus infection in inflammatory cortical lesions in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 72, 29–41 (2013).

Magliozzi, R. et al. Meningeal B-cell follicles in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis associate with early onset of disease and severe cortical pathology. Brain 130, 1089–1104 (2007).

Lucchinetti, C. F. et al. Inflammatory cortical demyelination in early multiple sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 365, 2188–2197 (2011).

Makshakov, G. et al. Leptomeningeal contrast enhancement is associated with disability progression and grey matter atrophy in multiple sclerosis. Neurol. Res. Int. 2017, 8652463 (2017).

Titelbaum, D. S. et al. Leptomeningeal enhancement on 3D-FLAIR MRI in multiple sclerosis: systematic observations in clinical practice. J. Neuroimaging 30, 917–929 (2020).

Absinta, M. et al. Gadolinium-based MRI characterization of leptomeningeal inflammation in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 85, 18–28 (2015).

Kappos, L. et al. Ocrelizumab in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a phase 2, randomised, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet 378, 1779–1787 (2011).

Steinman, L. Immunology of relapse and remission in multiple sclerosis. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 32, 257–281 (2014).

Bo, L., Geurts, J. J., Mork, S. J. & van der Valk, P. Grey matter pathology in multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol. Scand. Suppl. 183, 48–50 (2006).

Peters, A. et al. Th17 cells induce ectopic lymphoid follicles in central nervous system tissue inflammation. Immunity 35, 986–996 (2011).

Zuo, M. et al. Age-dependent gray matter demyelination is associated with leptomeningeal neutrophil accumulation. JCI Insight 7 (2022).

Ward, L. A. et al. Siponimod therapy implicates Th17 cells in a preclinical model of subpial cortical injury. JCI Insight 5 (2020).

Angst, D. et al. Discovery of LOU064 (remibrutinib), a potent and highly selective covalent inhibitor of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase. J. Med. Chem. 63, 5102–5118 (2020).

Nuesslein-Hildesheim, B. et al. Remibrutinib (LOU064) inhibits neuroinflammation driven by B cells and myeloid cells in preclinical models of multiple sclerosis. J. Neuroinflammation 20, 194 (2023).

Hao, Y. et al. Dictionary learning for integrative, multimodal and scalable single-cell analysis. Nat. Biotechnol. 42, 293–304 (2024).

Bhargava, P. et al. Imaging meningeal inflammation in CNS autoimmunity identifies a therapeutic role for BTK inhibition. Brain 144, 1396–1408 (2021).

Evonuk, K. S. et al. Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibition reduces disease severity in a model of secondary progressive autoimmune demyelination. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 11, 115 (2023).

Kramer, J., Bar-Or, A., Turner, T. J. & Wiendl, H. Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors for multiple sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 19, 289–304 (2023).

Siffrin, V. et al. In vivo imaging of partially reversible Th17 cell-induced neuronal dysfunction in the course of encephalomyelitis. Immunity 33, 424–436 (2010).

Langrish, C. L. et al. IL-23 drives a pathogenic T cell population that induces autoimmune inflammation. J. Exp. Med. 201, 233–240 (2005).

Wang, A. A. et al. B cell depletion with anti-CD20 promotes neuroprotection in a BAFF-dependent manner in mice and humans. Sci. Transl. Med. 16, eadi0295 (2024).

Absinta, M., Lassmann, H. & Trapp, B. D. Mechanisms underlying progression in multiple sclerosis. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 33, 277–285 (2020).

Calabrese, M. et al. The changing clinical course of multiple sclerosis: a matter of gray matter. Ann. Neurol. 74, 76–83 (2013).

Florescu, A. et al. Dynamic alterations of dural and bone marrow B cells in an animal model of progressive multiple sclerosis. J. Exp. Med. 222 (2025).

Gommerman, J. L. & Browning, J. L. Lymphotoxin/light, lymphoid microenvironments and autoimmune disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3, 642–655 (2003).

Kuprash, D. V. et al. Cyclosporin A blocks the expression of lymphotoxin alpha, but not lymphotoxin beta, in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Blood 100, 1721–1727 (2002).

Rennert, P. D., James, D., Mackay, F., Browning, J. L. & Hochman, P. S. Lymph node genesis is induced by signaling through the lymphotoxin beta receptor. Immunity 9, 71–79 (1998).

Ahmed, S. M. et al. Accumulation of meningeal lymphocytes correlates with white matter lesion activity in progressive multiple sclerosis. JCI Insight 7 (2022).

Benkert, P. et al. Serum neurofilament light chain for individual prognostication of disease activity in people with multiple sclerosis: a retrospective modelling and validation study. Lancet Neurol. 21, 246–257 (2022).

Abdelhak, A., Huss, A., Kassubek, J., Tumani, H. & Otto, M. Author correction: serum GFAP as a biomarker for disease severity in multiple sclerosis. Sci. Rep. 9, 8433 (2019).

Absinta, M. et al. A lymphocyte–microglia–astrocyte axis in chronic active multiple sclerosis. Nature 597, 709–714 (2021).

Maggi, P. et al. Paramagnetic rim lesions are specific to multiple sclerosis: an international multicenter 3T MRI study. Ann. Neurol. 88, 1034–1042 (2020).

Motamedgorji, N. et al. Characterizing iron rim lesions in multiple sclerosis: a biomarker for disease activity and progression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroradiology (2025).

Dal-Bianco, A., Oh, J., Sati, P. & Absinta, M. Chronic active lesions in multiple sclerosis: classification, terminology, and clinical significance. Ther. Adv. Neurol. Disord. 17, 17562864241306684 (2024).

Drayton, D. L., Ying, X., Lee, J., Lesslauer, W. & Ruddle, N. H. Ectopic LT alpha beta directs lymphoid organ neogenesis with concomitant expression of peripheral node addressin and a HEV-restricted sulfotransferase. J. Exp. Med. 197, 1153–1163 (2003).

Lu, T. T. & Browning, J. L. Role of the lymphotoxin/LIGHT system in the development and maintenance of reticular networks and vasculature in lymphoid tissues. Front. Immunol. 5, 47 (2014).

Cupedo, T. & Mebius, R. E. Role of chemokines in the development of secondary and tertiary lymphoid tissues. Semin. Immunol. 15, 243–248 (2003).

Magliozzi, R. et al. Inflammatory intrathecal profiles and cortical damage in multiple sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 83, 739–755 (2018).

Ansel, K. M. et al. A chemokine-driven positive feedback loop organizes lymphoid follicles. Nature 406, 309–314 (2000).

Kappos, L. et al. Atacicept in multiple sclerosis (ATAMS): a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 2 trial. Lancet Neurol. 13, 353–363 (2014).

Haselmayer, P. et al. Efficacy and pharmacodynamic modeling of the BTK inhibitor evobrutinib in autoimmune disease models. J. Immunol. 202, 2888–2906 (2019).

Kannel, K. et al. Changes in blood B cell-activating factor (BAFF) levels in multiple sclerosis: a sign of treatment outcome. PLoS ONE 10, e0143393 (2015).

Rojas, O. L. et al. Recirculating intestinal IgA-producing cells regulate neuroinflammation via IL-10. Cell 176, 610–624 e618 (2019).

Harrison, D. M. et al. Leptomeningeal enhancement at 7T in multiple sclerosis: frequency, morphology, and relationship to cortical volume. J. Neuroimaging 27, 461–468 (2017).

Zurawski, J. et al. 7T MRI cerebral leptomeningeal enhancement is common in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis and is associated with cortical and thalamic lesions. Mult. Scler. 26, 177–187 (2020).

Ramaglia, V., Florescu, A., Zuo, M., Sheikh-Mohamed, S. & Gommerman, J. L. Stromal cell-mediated coordination of immune cell recruitment, retention, and function in brain-adjacent regions. J. Immunol. 206, 282–291 (2021).

Ramaglia, V., Rojas, O., Naouar, I. & Gommerman, J. L. The ins and outs of central nervous system inflammation-lessons learned from multiple sclerosis. Annu Rev. Immunol. 39, 199–226 (2021).

Ighani, M. et al. No association between cortical lesions and leptomeningeal enhancement on 7-tesla MRI in multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. 26, 165–176 (2020).

Stern, J. N. et al. B cells populating the multiple sclerosis brain mature in the draining cervical lymph nodes. Sci. Transl. Med. 6, 248ra107 (2014).

Roosendaal, S. D. et al. Grey matter volume in a large cohort of MS patients: relation to MRI parameters and disability. Mult. Scler. 17, 1098–1106 (2011).

Furby, J. et al. Different white matter lesion characteristics correlate with distinct grey matter abnormalities on magnetic resonance imaging in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. 15, 687–694 (2009).

Sanfilipo, M. P., Benedict, R. H., Sharma, J., Weinstock-Guttman, B. & Bakshi, R. The relationship between whole brain volume and disability in multiple sclerosis: a comparison of normalized gray vs. white matter with misclassification correction. NeuroImage 26, 1068–1077 (2005).

De Stefano, N. et al. Evidence of early cortical atrophy in MS: relevance to white matter changes and disability. Neurology 60, 1157–1162 (2003).

Gruber, R. C. et al. BTK regulates microglial function and neuroinflammation in human stem cell models and mouse models of multiple sclerosis. Nat. Commun. 15, 10116 (2024).

Langlois, J. et al. Fenebrutinib, a Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor, blocks distinct human microglial signaling pathways. J. Neuroinflammation 21, 276 (2024).

Kim, J. S. et al. Clonal hematopoiesis-associated motoric deficits caused by monocyte-derived microglia accumulating in aging mice. Cell Rep. 44, 115609 (2025).

Vu, F., Dianzani, U., Ware, C. F., Mak, T. & Gommerman, J. L. ICOS, CD40, and lymphotoxin beta receptors signal sequentially and interdependently to initiate a germinal center reaction. J. Immunol. 180, 2284–2293 (2008).

Kil, L. P. et al. Btk levels set the threshold for B-cell activation and negative selection of autoreactive B cells in mice. Blood 119, 3744–3756 (2012).

Brunner, C., Avots, A., Kreth, H. W., Serfling, E. & Schuster, V. Bruton’s tyrosine kinase is activated upon CD40 stimulation in human B lymphocytes. Immunobiology 206, 432–440 (2002).

Luchetti, S. et al. Progressive multiple sclerosis patients show substantial lesion activity that correlates with clinical disease severity and sex: a retrospective autopsy cohort analysis. Acta Neuropathol. 135, 511–528 (2018).

Frischer, J. M. et al. The relation between inflammation and neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis brains. Brain 132, 1175–1189 (2009).

Michailidou, I. et al. Complement C1q–C3-associated synaptic changes in multiple sclerosis hippocampus. Ann. Neurol. 77, 1007–1026 (2015).

Bagnato, F. et al. Imaging chronic active lesions in multiple sclerosis: a consensus statement. Brain 147, 2913–2933 (2024).

Gauthier, A. et al. Comparison of Simoa and Ella to assess serum neurofilament-light chain in multiple sclerosis. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 8, 1141–1150 (2021).

Giuliani, F., Fu, S. A., Metz, L. M. & Yong, V. W. Effective combination of minocycline and interferon-beta in a model of multiple sclerosis. J. Neuroimmunol. 165, 83–91 (2005).

Galicia, G. et al. Isotype-switched autoantibodies are necessary to facilitate central nervous system autoimmune disease in Aicda−/− and Ung−/− mice. J. Immunol. 201, 1119–1130 (2018).

Arbabi, A. et al. Multiple-mouse magnetic resonance imaging with cryogenic radiofrequency probes for evaluation of brain development. NeuroImage 252, 119008 (2022).

Spencer Noakes, T. L., Henkelman, R. M. & Nieman, B. J. Partitioning k-space for cylindrical three-dimensional rapid acquisition with relaxation enhancement imaging in the mouse brain. NMR Biomed. https://doi.org/10.1002/nbm.3802 (2017).

Collins, D. L., Neelin, P., Peters, T. M. & Evans, A. C. Automatic 3D intersubject registration of MR volumetric data in standardized Talairach space. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 18, 192–205 (1994).

Avants, B. B. et al. A reproducible evaluation of ANTs similarity metric performance in brain image registration. NeuroImage 54, 2033–2044 (2011).

Chakravarty, M. M. et al. Performing label-fusion-based segmentation using multiple automatically generated templates. Hum. Brain Mapp. 34, 2635–2654 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Multiple Sclerosis Society grant no. RFA-2203-39259 to J.L.G. and V.R., by the MS Canada grant no. 1423841 to J.L.G., by the CIHR (Aging Research Program) grant no. 525895, by Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs through the (Multiple Sclerosis Research Program) under award no. HT9425-23-1-0933 to J.L.G. and V.R., and by the Canada Research Chair in Tissue Specific Immunity to J.L.G. Opinions, interpretations, conclusions and recommendations presented in this paper are those of the authors and are not necessarily endorsed by the Department of Defense. This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke of the National Institutes of Health (ZIA NS003119, D.S.R.). The contributions of the NIH authors are considered Works of the US Government. The findings and conclusions presented in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NIH or the US Department of Health and Human Services. We thank R. Jupp from Mestag Therapeutics for providing the αLTβR agonist.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.N., V.R., M.Z., K.C.-J., A.W., A. Pangan, A. Pu and L.W. contributed to the induction and monitoring of the EAE experiments. I.N., V.R., A. Pangan, J.P. and F.N.S. performed the immunostaining and analyses of the mouse brain tissues. J.S.Y.A. performed the dissection and the qPCR analysis of the leptomeninges in the animal studies. B.C. and B.N.-H. advised on the experiments and performed the BTKi occupancy assays. A.-K.P. and E.P. performed the quantification and analyses of serum NfL in the animal studies. S.S. and J.G.S. performed the mouse MRI measurements. V.R. and J.Z. performed the quantification and analysis of the CSF NfL, GFAP, BAFF and CXCL13 in the post mortem MS cohort. S.A.R. and D.S.R. performed the quantification and analysis of the CSF NfL, GFAP, BAFF and CXCL13 in the living MS cohort. J.L.B. advised of LT biology. J.L.G. and V.R. designed the study and wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

J.L.G. has a shared patent on ‘Methods of treating an autoimmune disease’: WO2020102895A1, US20210401939A1, EP3883593A4 and CA3120454A1. The patent provides methods of treating an autoimmune disease (for example, multiple sclerosis) or reducing inflammation by administering at least a B cell activating Factor (BAFF) polypeptide to a subject in need thereof. The effect of BAFF on plasmablast/plasma cells and their role in autoimmune diseases is also disclosed. D.S.R. has received research funding from Abata and Sanofi, related to but separate from his contribution to the current work. The other authors declare no competing interests. B.C. and B.N.-H. are employees of Novartis.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Immunology thanks David Hafler and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available. Primary Handling Editor: L.A. Dempsey, in collaboration with the Nature Immunology team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Prophylactic BTK inhibition does not affect clinical outcome or serum neurofilament light (NfL) levels in SJL/J adoptive transfer EAE mice.

(a) Female 6- to 10-week-old SJL/J mice received an adoptive transfer of 10 million encephalitogenic TH17 cells to induce EAE. Mice were treated via oral gavage with 30 mg/kg Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor (BTKi, Remibrutinib, (LOU064) or vehicle control twice a day prophylactically from day 3 to day 11 after adoptive transfer and were harvested at peak EAE (day 12 after adoptive transfer). (b, c) BTK occupancy in the spleen and brain of vehicle-treated (n = 5 for each) or BTKi-treated (n = 7 for each) SJL/J adoptive transfer EAE mice at peak disease. (d–g) Clinical scores and area under the curves (AUC) of the clinical scores in 2 experiments where SJL/J adoptive transfer EAE mice were treated with the BTK inhibitor (n = 10 and n = 7) or vehicle control (n = 10 and n = 6) prophylactically. (h) Serum neurofilament light chain (NfL) in naïve (n = 4), vehicle-treated (n = 4) and BTKi-treated (n = 7) mice at peak disease. (i) Correlation between the AUC and the amount of serum NfL in vehicle–treated or BTKi–treated (n = 8) SJL/J adoptive transfer EAE mice at peak disease. Data are shown as means ± SD. Statistical analysis in b, c, e, g was conducted using a two-sided Mann–Whitney test. Statistical analysis in H was conducted using a two-sided Kruskal–Wallis test with post hoc Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. Statistical analysis in d, f was conducted using a One-Way ANOVA test with post hoc Bonferroni multiple comparisons test. Correlation analysis in i was conducted using two-sided Pearson correlation coefficient. *P ≤ 0.05 and **P ≤ 0.01. (b):p = 0.002, (c):p = 0.0051, (h): naïve vs vehicle-treated p = 0.0216 and naïve vs BTKi-treated p = 0.0403.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Prophylactic BTK inhibition does not affect spinal cord pathology in SJL/J adoptive transfer EAE mice.

Histology and immunohistochemical staining of spinal cord tissue from naïve (a), prophylactically vehicle–treated (b) and BTK inhibitor (BTKi)–treated (c) SJL/J adoptive transfer EAE mice at peak disease (day 12 after adoptive transfer) for H&E visualizing inflammation, luxol fast blue (LFB) visualizing myelin, ionized calcium binding adapter molecule 1 (IBA1) visualizing microglia and macrophages and neurofilament light chain (NfL) visualizing axons. Black arrowheads indicate the inflamed and damaged spinal cord white matter area. (d) Quantification of a-c. Data are shown as means ± SD. Statistical analysis was conducted using Kruskal–Wallis tests with post hoc Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. P > 0.05. (naïve: n = 5, 5, 7 and 7 respectively), (vehicle-treated: n = 10 for each graph), (BTKi–treated: n = 10 for each graph).

Extended Data Fig. 3 Therapeutic BTK inhibition spares the glial limitans, reduces cortical gray matter demyelination, myeloid cell accumulation and axonal loss in SJL/J adoptive transfer EAE.

Immunohistochemical staining of somatosensory cortex tissue from naïve, therapeutically vehicle–treated and BTK inhibitor (BTKi)–treated SJL/J adoptive transfer EAE mice at peak disease (day 12 after adoptive transfer) for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) visualizing the glial limitans (a), proteolipid protein (PLP) visualizing myelin (b), ionized calcium binding adapter molecule 1 (IBA1) visualizing microglia and macrophages (c) and neurofilament light chain (NfL) visualizing axons (d). White arrowheads in a indicate the glial limitans; in c indicate microglia/macrophages.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Therapeutic BTK inhibition does not affect clinical outcome in old SJL/J adoptive transfer EAE mice.

a) Female 8 to 12 moths-old SJL/J mice received an adoptive transfer of 10 million encephalitogenic TH17 cells to induce EAE. Mice were treated via oral gavage with 30 mg/kg Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor (BTKi, Remibrutinib, LOU064) or vehicle control twice a day therapeutically from day 9 to day 21 post-adoptive transfer (b, c) when the tissue was harvested for pathology assessment or day 39 post-adoptive transfer (d, e) when the tissue was harvested for MRI assessment. Timeline and area under the curves (AUC) of the clinical scores from the pathology (b, c; n = 5 for BTKi treated and n = 5 for vehicle treated mice) and the MRI (d, e; n = 7 for BTKi treated and n = 7 for vehicle treated mice) experiments. Data are shown as means ± SD. Statistical analysis in B and D was conducted using a two-sided One-Way ANOVA test with post hoc Bonferroni multiple comparisons test. Statistical analysis in C and E was conducted using a two-sided Mann–Whitney test.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Effects of prophylactic or therapeutic BTK inhibition on leptomeningeal TLTs in SJL/J adoptive transfer EAE mice.

Representative hematoxylin & Eosin (H&E)–stained sections of the leptomeninges overlaying the hippocampi (a, b), hypothalami (c, d), cerebelli (e, f) and brainstems (g, h) of vehicle–treated or BTK inhibitor (BTKi)–treated SJL/J adoptive transfer EAE mice at peak disease (day 12 after adoptive transfer). Quantification of the number and size of leptomeningeal TLTs shown in A-H for the prophylactic (i) or therapeutic (j) treatment modality. Data are shown as means ± SD. Statistical analysis was conducted using two-sided multiple Mann–Whitney tests. ns, not significant; *P ≤ 0.05. (vehicle-treated: n = 7 for each treatment modality), (BTKi–treated: n = 7 for each treatment modality).

Extended Data Fig. 6 Effects of prophylactic or therapeutic BTK inhibition on leptomeningeal B and T cells in SJL/J adoptive transfer EAE mice.

Histological score of B220+ B cells and CD3+ T cells in the leptomeninges of prophylactically (a) or therapeutically (b) vehicle–treated or BTK inhibitor (BTKi)–treated SJL/J adoptive transfer EAE mice at peak disease (day 12 after adoptive transfer). Data are shown as means ± SD Statistical analysis was conducted using multiple Mann–Whitney tests. ns, not significant; *P ≤ 0.05. (a) B220, p = 0.011994; CD3, p = 0.003767. (b) B220, hippocampus p = 0.020979; hypothalamus p = 0.028571; cerebellum p = 0.011072. CD3, cerebellum p = 0.049534. n = 7 (vehicle-treated), 7 (BTKi–treated).

Extended Data Fig. 7 Gating strategy for B cells treated with BTKi.

a) Gating strategy for B cells. (b) Representative plots of LTβ+CD19+B220+ B cells from naive SJL/J splenocytes either unstimulated or stimulated with mouse anti-CD40 (5ug/ml) + LPS (1ug/ml) ex vivo after pre-treatment with BTKi (10 nM) or equivalent Vol of culture medium for 1 h.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Prophylactic BTK inhibition does not impact the pro-inflammatory profile of T cells in the leptomeninges of SJL/J adoptive transfer EAE mice.

Flow cytometry quantification of interferon (IFN)-γ (a), interleukin (IL)-17A (b) and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (c) production by CD3+CD4+ T cells from single cell suspensions isolated from the leptomeninges and stimulated for 4 h in 1X Cell Stimulation Cocktail with 1X Brefeldin A. (d) Gating strategy of a-c. Data are shown as means ± SD.Statistical analysis was conducted using a two-sided Mann–Whitney test. ns, not significant. n = 5 (vehicle-treated), 7 (BTKi–treated).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Tables 1 and 2, and Methods.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 7

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 8

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 8

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Naouar, I., Pangan, A., Zuo, M. et al. Lymphotoxin-dependent elevated meningeal CXCL13:BAFF ratios drive gray matter injury. Nat Immunol 27, 48–60 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41590-025-02359-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41590-025-02359-5