Abstract

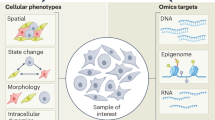

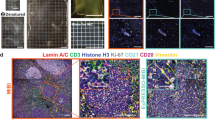

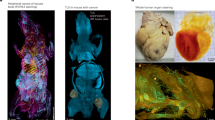

Omics technologies such as genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics and metabolomics methods, have been instrumental in improving our understanding of complex biological systems by providing high-dimensional phenotypes of cell populations and single cells. Despite fast-paced advancements, these methods are limited in their ability to include a temporal dimension. Here, we introduce ESPRESSO (Environmental Sensor Phenotyping RElayed by Subcellular Structures and Organelles), a technique that provides single-cell, high-dimensional phenotyping resolved in space and time. ESPRESSO combines fluorescent labeling, advanced microscopy and image and data analysis methods to extract morphological and functional information from organelles at the single-cell level. We validate ESPRESSO’s methodology and its application across numerous cellular systems for the analysis of cell type, stress response, differentiation and immune cell polarization. We show that ESPRESSO can correlate phenotype changes with gene expression, and demonstrate its applicability to 3D cultures, offering a path to improved spatially and temporally resolved biological exploration of cellular states.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Demonstration data are available from Zenodo: https://zenodo.org/records/12737891 (ref. 79). Due to data size constraints, imaging data can be requested from Lorenzo Scipioni (lorenzo.scipioni@inserm.fr).

Code availability

Demonstration code is available from Zenodo: https://zenodo.org/records/12737891, scRNA-seq analysis can be found at https://github.com/yl-jia/ESPRESSO.

References

Wang, Z., Gerstein, M. & Snyder, M. RNA-Seq: a revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 10, 57–63 (2009).

Cui, M., Cheng, C. & Zhang, L. High-throughput proteomics: a methodological mini-review. Lab. Invest. 102, 1170–1181 (2022).

Johnson, C. H., Ivanisevic, J. & Siuzdak, G. Metabolomics: beyond biomarkers and towards mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 17, 451–459 (2016).

Lewis, S. M. et al. Spatial omics and multiplexed imaging to explore cancer biology. Nat. Methods 18, 997–1012 (2021).

Valm, A. M. et al. Applying systems-level spectral imaging and analysis to reveal the organelle interactome. Nature 546, 162–167 (2017).

Jain, A. & Zoncu, R. Organelle transporters and inter-organelle communication as drivers of metabolic regulation and cellular homeostasis. Mol. Metab. 60, 101481 (2022).

Kim, Y. et al. Characterizing organelles in live stem cells using label-free optical diffraction tomography. Mol. Cells 44, 851–860 (2021).

Ahlqvist, K. J., Suomalainen, A. & Hämäläinen, R. H. Stem cells, mitochondria and aging. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1847, 1380–1386 (2015).

Jarc, E. & Petan, T. Lipid droplets and the management of cellular stress. Yale J. Biol. Med. 92, 435–452 (2019).

Frank, M. et al. Mitophagy is triggered by mild oxidative stress in a mitochondrial fission dependent manner. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1823, 2297–2310 (2012).

Mukhopadhyay, S. et al. Serum starvation induces anti-apoptotic cIAP1 to promote mitophagy through ubiquitination. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 479, 940–946 (2016).

Cruz, A. L. S., Barreto, E. A., Fazolini, N. P. B., Viola, J. P. B. & Bozza, P. T. Lipid droplets: platforms with multiple functions in cancer hallmarks. Cell Death Dis. 11, 105 (2020).

Rambold, A. S., Cohen, S. & Lippincott-Schwartz, J. Fatty acid trafficking in starved cells: regulation by lipid droplet lipolysis, autophagy, and mitochondrial fusion dynamics. Dev. Cell 32, 678–692 (2015).

Loeffler, D. et al. Asymmetric organelle inheritance predicts human blood stem cell fate. Blood 139, 2011–2023 (2022).

Bray, M. A. et al. Cell Painting, a high-content image-based assay for morphological profiling using multiplexed fluorescent dyes. Nat. Protoc. 11, 1757–1774 (2016).

Novikova, S. et al. Nuclear proteomics of induced leukemia cell differentiation. Cells 11, 3221 (2022).

Chikte, S., Panchal, N. & Warnes, G. Use of LysoTracker dyes: a flow cytometric study of autophagy. Cytometry A 85, 169–178 (2014).

Scaduto, R. C. & Grotyohann, L. W. Measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential using fluorescent rhodamine derivatives. Biophys. J. 76, 469–477 (1999).

Cutrale, F. et al. Hyperspectral phasor analysis enables multiplexed 5D in vivo imaging. Nat. Methods 14, 149–152 (2017).

Scipioni, L., Rossetta, A., Tedeschi, G. & Gratton, E. Phasor S-FLIM: a new paradigm for fast and robust spectral fluorescence lifetime imaging. Nat. Methods 18, 542–550 (2021).

Fereidouni, F., Bader, A. N. & Gerritsen, H. C. Spectral phasor analysis allows rapid and reliable unmixing of fluorescence microscopy spectral images. Opt. Express 20, 12729 (2012).

Cutrale, F., Salih, A. & Gratton, E. Spectral phasor approach for fingerprinting of photo-activatable fluorescent proteins Dronpa, Kaede and KikGR. Methods Appl. Fluoresc. 1, 35001 (2013).

von Chamier, L. et al. Democratising deep learning for microscopy with ZeroCostDL4Mic. Nat. Commun. 12, 2276 (2021).

Weigert, M. et al. Content-aware image restoration: pushing the limits of fluorescence microscopy. Nat. Methods 15, 1090–1097 (2018).

Stringer, C., Wang, T., Michaelos, M. & Pachitariu, M. Cellpose: a generalist algorithm for cellular segmentation. Nat. Methods 18, 100–106 (2021).

Kolin, D. L. & Wiseman, P. W. Advances in image correlation spectroscopy: measuring number densities, aggregation states, and dynamics of fluorescently labeled macromolecules in cells. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 49, 141–164 (2007).

Scipioni, L., Gratton, E., Diaspro, A. & Lanzanò, L. Phasor analysis of local ICS detects heterogeneity in size and number of intracellular vesicles. Biophys. J. 111, 619–629 (2016).

Costantino, S., Comeau, J. W. D., Kolin, D. L. & Wiseman, P. W. Accuracy and dynamic range of spatial image correlation and cross-correlation spectroscopy. Biophys. J. 89, 1251–1260 (2005).

Oneto, M. et al. Nanoscale distribution of nuclear sites by super-resolved image cross-correlation spectroscopy. Biophys. J. 117, 2054–2065 (2019).

Petersen, N. O., Höddelius, P. L., Wiseman, P. W., Seger, O. & Magnusson, K. E. Quantitation of membrane receptor distributions by image correlation spectroscopy: concept and application. Biophys. J. 65, 1135–1146 (1993).

Liang, Z., Lou, J., Scipioni, L., Gratton, E. & Hinde, E. Quantifying nuclear wide chromatin compaction by phasor analysis of histone Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) in frequency domain fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) data. Data Brief 30, 105401 (2020).

Lou, J. et al. Phasor histone FLIM-FRET microscopy quantifies spatiotemporal rearrangement of chromatin architecture during the DNA damage response. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 7323–7332 (2019).

Wang, Y., Huang, H., Rudin, C. & Shaposhnik, Y. Understanding how dimension reduction tools work: an empirical approach to deciphering T-SNE, UMAP, TriMap, and PaCMAP for data visualization. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 22, 1–73 (2021).

Fraley, C. & Raftery, A. E. Model-based clustering, discriminant analysis, and density estimation. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 97, 611–631 (2002).

Xiao, J., Lu, J. & Li, X. Davies Bouldin Index based hierarchical initialization K-means. Intell. Data Anal. 21, 1327–1338 (2017).

Dickson, M. A. et al. Human keratinocytes that express hTERT and also bypass a p16(INK4a)-enforced mechanism that limits life span become immortal yet retain normal growth and differentiation characteristics. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 1436–1447 (2000).

Tedeschi, G. et al. Monitoring macrophage polarization with gene expression reporters and bioluminescence phasor analysis. Chem. Biomed. Imaging 2, 765–774 (2024).

Iriondo, O. et al. Distinct breast cancer stem/progenitor cell populations require either HIF1α or loss of PHD3 to expand under hypoxic conditions. Oncotarget 6, 31721–31739 (2015).

Li, Q., Ma, R. & Zhang, M. CoCl2 increases the expression of hypoxic markers HIF-1α, VEGF and CXCR4 in breast cancer MCF-7 cells. Oncol. Lett. 15, 1119–1124 (2018).

Bai, F. et al. Simvastatin induces breast cancer cell death through oxidative stress up-regulating miR-140-5p. Aging 11, 3198–3219 (2019).

Wang, R. et al. Molecular basis of V-ATPase inhibition by bafilomycin A1. Nat. Commun. 12, 1782 (2021).

Dispersyn, G., Nuydens, R., Connors, R., Borgers, M. & Geerts, H. Bcl-2 protects against FCCP-induced apoptosis and mitochondrial membrane potential depolarization in PC12 cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1428, 357–371 (1999).

Sun, Y., Jiang, X., Chen, S. & Price, B. D. Inhibition of histone acetyltransferase activity by anacardic acid sensitizes tumor cells to ionizing radiation. FEBS Lett. 580, 4353–4356 (2006).

Tóth, K. F. et al. Trichostatin A-induced histone acetylation causes decondensation of interphase chromatin. J. Cell Sci. 117, 4277–4287 (2004).

Mylonis, I. et al. Hypoxia causes triglyceride accumulation by HIF-1-mediated stimulation of lipin 1 expression. J. Cell Sci. 125, 3485–3493 (2012).

Munir, R., Lisec, J., Swinnen, J. V. & Zaidi, N. Lipid metabolism in cancer cells under metabolic stress. Br. J. Cancer 120, 1090–1098 (2019).

Jones, S. P., Teshima, Y., Akao, M. & Marbán, E. Simvastatin attenuates oxidant-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in cardiac myocytes. Circ. Res. 93, 697–699 (2003).

Zhang, Y. et al. Simvastatin improves lysosome function via enhancing lysosome biogenesis in endothelial cells. Front. Biosci. Landmark Ed. 25, 283–298 (2020).

Liu, B., Zhu, F., Xia, X., Park, E. & Hu, Y. A tale of terminal differentiation: IKKα, the master keratinocyte regulator. Cell Cycle 8, 527–531 (2009).

Monteleon, C. L. et al. Lysosomes support the degradation, signaling, and mitochondrial metabolism necessary for human epidermal differentiation. J. Invest. Dermatol. 138, 1945–1954 (2018).

Gdula, M. R. et al. Remodeling of three-dimensional organization of the nucleus during terminal keratinocyte differentiation in the epidermis. J. Invest. Dermatol. 133, 2191–2201 (2013).

Charest, J. L., Jennings, J. M., King, W. P., Kowalczyk, A. P. & García, A. J. Cadherin-mediated cell–cell contact regulates keratinocyte differentiation. J. Invest. Dermatol. 129, 564–572 (2009).

Wynn, T. A., Chawla, A. & Pollard, J. W. Macrophage biology in development, homeostasis and disease. Nature 496, 445–455 (2013).

Chen, S. et al. Macrophages in immunoregulation and therapeutics. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 8, 207 (2023).

Xaus, J. et al. LPS induces apoptosis in macrophages mostly through the autocrine production of TNF-α. Blood 95, 3823–3831 (2000).

Nayak, P., Bentivoglio, V., Varani, M. & Signore, A. Three-dimensional in vitro tumor spheroid models for evaluation of anticancer therapy: recent updates. Cancers 15, 4846 (2023).

Ziperstein, M. J., Guzman, A. & Kaufman, L. J. Breast cancer cell line aggregate morphology does not predict invasive capacity. PLoS One 10, e0139523 (2015).

Lee, S.-Y., Koo, I.-S., Hwang, H. J. & Lee, D. W. In vitro three-dimensional (3D) cell culture tools for spheroid and organoid models. SLAS Discov. 28, 119–137 (2023).

Huang, Z., Yu, P. & Tang, J. Characterization of triple-negative breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cell spheroid model. Onco Targets Ther. 13, 5395–5405 (2020).

Hofmann, S., Cohen-Harazi, R., Maizels, Y. & Koman, I. Patient-derived tumor spheroid cultures as a promising tool to assist personalized therapeutic decisions in breast cancer. Transl. Cancer Res. 11, 134–147 (2022).

Gilazieva, Z., Ponomarev, A., Rutland, C., Rizvanov, A. & Solovyeva, V. Promising applications of tumor spheroids and organoids for personalized medicine. Cancers 12, 2727 (2020).

Yao, Z. et al. Multiplexed bioluminescence microscopy via phasor analysis. Nat. Methods 19, 893–898 (2022).

Tedeschi, G., Palomba, F., Scipioni, L. & Digman, M. A. Multimodal phasor approach to study breast cancer cell invasion in a 3D spheroid model. Chem. Biomed. Imaging 3, 433–442 (2025).

Reynolds, D. S. et al. Breast cancer spheroids reveal a differential cancer stem cell response to chemotherapeutic treatment. Sci. Rep. 7, 10382 (2017).

A. Naveena, H. & Bhatia, D. Hypoxia modulates cellular endocytic pathways and organelles with enhanced cell migration and 3D cell invasion. Chembiochem 24, e202300506 (2023).

Bytautaite, M. & Petrikaite, V. Comparative study of lipophilic statin activity in 2D and 3D in vitro models of human breast cancer cell lines MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7. Onco Targets Ther. 13, 13201–13209 (2020).

Held, M. et al. CellCognition: time-resolved phenotype annotation in high-throughput live cell imaging. Nat. Methods 7, 747–754 (2010).

Viana, M. P. et al. Integrated intracellular organization and its variations in human iPS cells. Nature 613, 345–354 (2023).

Kobayashi-Kirschvink, K. J. et al. Prediction of single-cell RNA expression profiles in live cells by Raman microscopy with Raman2RNA. Nat. Biotechnol. 42, 1726–1734 (2024).

Wiggins, L. et al. The CellPhe toolkit for cell phenotyping using time-lapse imaging and pattern recognition. Nat. Commun. 14, 1854 (2023).

Suzuki, K. et al. Five colour variants of bright luminescent protein for real-time multicolour bioimaging. Nat. Commun. 7, 13718 (2016).

Palla, G. et al. Squidpy: a scalable framework for spatial omics analysis. Nat. Methods 19, 171–178 (2022).

Lun, A. T. L. et al. EmptyDrops: distinguishing cells from empty droplets in droplet-based single-cell RNA sequencing data. Genome Biol. 20, 63 (2019).

McGinnis, C. S., Murrow, L. M. & Gartner, Z. J. DoubletFinder: doublet detection in single-cell RNA sequencing data using artificial nearest neighbors. Cell Syst. 8, 329–337 (2019).

Germain, P.-L., Lun, A., Meixide, C. G., Macnair, W. & Robinson, M. D. Doublet identification in single-cell sequencing data using scDblFinder. F1000Res 10, 979 (2022).

Gulati, G. S. et al. Single-cell transcriptional diversity is a hallmark of developmental potential. Science 367, 405–411 (2020).

Enzo, E. et al. Single-keratinocyte transcriptomic analyses identify different clonal types and proliferative potential mediated by FOXM1 in human epidermal stem cells. Nat. Commun. 12, 2505 (2021).

Borcherding, N. et al. Mapping the immune environment in clear cell renal carcinoma by single-cell genomics. Commun. Biol. 4, 122 (2021).

Scipioni, L. Demo code for ‘ESPRESSO: spatiotemporal omics based on organelle phenotyping’: https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.06.13.598932. Zenodo (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funds from the Fondation Toulouse Cancer Santé (Chaire Oncobreast to L.S.), the National Science Foundation grants CBET2134916 to S.X.A. and Y.Y.J. and 1847005 to M.A.D., and the Allen Distinguished Investigator Award, a Paul G. Allen Frontiers Group advised grant of the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation (to J.A.P. and M.A.D.). The authors acknowledge the support of the Laboratory for Fluorescence Dynamics (P41GM103540), the American Italian Cancer Foundation (to M.D.B.), the Chao Family Comprehensive Cancer Center Genomics High-Throughput Facility Shared Resource, supported by the NCI of the NIH under award no. P30CA062203, and the UCI Skin Biology Resource Center supported by NIAMS under award no. P30AR075047.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.S. conceived the idea, performed experiments and wrote code. G.T. conceived the idea and performed experiments. M.X.N. generated the RAW246.7-NOS2 cell line. Y.Y.J. performed and analyzed the scRNA-seq experiments. Y.Y.J. and S.X.A. advised on the keratinocytes experiments and interpretation. S.Z. performed the cell cycle experiment. L.P.H. performed the viability assays. M.D.B. provided reagents and helped with interpretation. S.X.A., J.A.P., E.G. and M.A.D. provided support and supervised the project. L.S. took the lead in writing the manuscript. All authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the research, analysis and manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Methods thanks Sang-Hee Shim and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Madhura Mukhopadhyay, in collaboration with the Nature Methods team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–13, Table 1.

Supplementary Video 1

ESPRESSO Phenotype evolution in keratinocytes – Control Conditions. PacMAP for each individual time point (left) for the keratinocyte differentiation experiment (Control condition) shown in Fig. 3. Each point represents a cell detected in the corresponding frame (right). Points in the scatter plot (left) and cell masks in the image (right) are color-coded according to the cluster they belong to, following the same color-code as in Fig. 3.

Supplementary Video 2

ESPRESSO Phenotype evolution in keratinocytes – Calcium-induced differentiation. PacMAP for each individual time point (left) for the keratinocyte differentiation experiment (Calcium-induced differentiation condition) shown in Fig. 3. Each point represents a cell detected in the corresponding frame (right). Points in the scatter plot (left) and cell masks in the image (right) are color-coded according to the cluster they belong to, following the same color-code as in Fig. 3.

Supplementary Code

Code details.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Scipioni, L., Tedeschi, G., Navarro, M.X. et al. ESPRESSO: spatiotemporal omics based on organelle phenotyping. Nat Methods 22, 2349–2361 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-025-02863-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-025-02863-4