Abstract

Premetastatic cancer cells often spread from the primary lesion through the lymphatic vasculature and, clinically, the presence or absence of lymph node metastases impacts treatment decisions. However, little is known about cancer progression via the lymphatic system or of the effect that the lymphatic environment has on cancer progression. This is due, in part, to the technical challenge of studying lymphatic vessels and collecting lymph fluid. Here we provide a step-by-step procedure to collect both lymph and tumor-draining lymph in mouse models of cancer metastasis. This protocol has been adapted from established methods of lymph collection and was developed specifically for the collection of lymph from tumors. The approach involves the use of mice bearing melanoma or breast cancer orthotopic tumors. After euthanasia, the cisterna chyli and the tumor are exposed and viewed using a stereo microscope. Then, a glass cannula connected to a 1 mL syringe is inserted directly into the cisterna chyli or the tumor-draining lymphatics for collection of pure lymph. These lymph samples can be used to analyze the lymph-derived cancer cells using highly sensitive multiomics approaches to investigate the impact of the lymph environment during cancer metastasis. The procedure requires 2 h per mouse to complete and is suitable for users with minimal expertise in small animal handling and use of microsurgical tools under a stereo microscope.

Key points

-

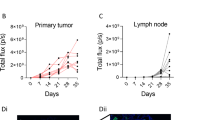

The elevated pressure in the lymphatics around the tumor is leveraged for the collection of lymph from each tumor and the subsequent metabolic and lipidomic characterization using mass spectrometry, as well as lymph-derived cell characterization by flow cytometry.

-

Lymph can be alternatively collected by cannulating the thoracic duct; however, this requires surgery and specialized equipment, and has not been applied to tumor-draining lymphatics.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The authors declare that the main data discussed in this protocol are available in the supporting primary research paper as ‘source data’ (https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2623-z). All photographic images shown in this manuscript are the original, unaltered photographs. The deidentified metabolomics heat map contains no source data, as it is provided as a representative example of the protocol application.

Change history

10 February 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41596-025-01156-6

References

Leong, S. P. et al. Clinical patterns of metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 25, 221–232 (2006).

Sleeman, J., Schmid, A. & Thiele, W. Tumor lymphatics. Semin. Cancer Biol. 19, 285–297 (2009).

Fink, D. M., Steele, M. M. & Hollingsworth, M. A. The lymphatic system and pancreatic cancer. Cancer Lett. 381, 217–236 (2016).

Padera, T. P., Meijer, E. F. & Munn, L. L. The lymphatic system in disease processes and cancer progression. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 18, 125–158 (2016).

Amin, M., Greene, F., Edge, S. & Byrd, D. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual 8th edn (Springer, 2017).

Fares, J., Fares, M. Y., Khachfe, H. H., Salhab, H. A. & Fares, Y. Molecular principles of metastasis: a hallmark of cancer revisited. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 5, 28 (2020).

Oliver, G., Kipnis, J., Randolph, G. J. & Harvey, N. L. The lymphatic vasculature in the 21st century: Novel functional roles in homeostasis and disease. Cell 182, 270–296 (2020).

Rofstad, E. K., Galappathi, K. & Mathiesen, B. S. Tumor interstitial fluid pressure-a link between tumor hypoxia, microvascular density, and lymph node metastasis. Neoplasia 16, 586–594 (2014).

Broggi, M. A. S. et al. Tumor-associated factors are enriched in lymphatic exudate compared to plasma in metastatic melanoma patients. J. Exp. Med. 216, 1091–1107 (2019).

Boucher, Y., Baxter, L. T. & Jain, R. K. Interstitial pressure gradients in tissue-isolated and subcutaneous tumors: implications for therapy. Cancer Res. 50, 4478–4484 (1990).

Rofstad, E. K. et al. Pulmonary and lymph node metastasis is associated with primary tumor interstitial fluid pressure in human melanoma xenografts. Cancer Res. 62, 661–664 (2002).

Dadiani, M. et al. Real-time imaging of lymphogenic metastasis in orthotopic human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 66, 8037–8041 (2006).

Polacheck, W. J., Charest, J. L. & Kamm, R. D. Interstitial flow influences direction of tumor cell migration through competing mechanisms. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 11115–11120 (2011).

Hompland, T., Ellingsen, C., Ovrebo, K. M. & Rofstad, E. K. Interstitial fluid pressure and associated lymph node metastasis revealed in tumors by dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI. Cancer Res. 72, 4899–4908 (2012).

Reticker-Flynn, N. E. & Engleman, E. G. Lymph nodes: at the intersection of cancer treatment and progression. Trends Cell Biol. 33, 1021–1034 (2023).

Pereira, E. R. et al. Lymph node metastases can invade local blood vessels, exit the node, and colonize distant organs in mice. Science 359, 1403–1407 (2018).

Brown, M. et al. Lymph node blood vessels provide exit routes for metastatic tumor cell dissemination in mice. Science 359, 1408–1411 (2018).

Che Bakri, N. A. et al. Impact of axillary lymph node dissection and sentinel lymph node biopsy on upper limb morbidity in breast cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Surg. 277, 572–580 (2023).

Xu, Z. Y. et al. Seizing the fate of lymph nodes in immunotherapy: to preserve or not? Cancer Lett. 588, 216740 (2024).

Reticker-Flynn, N. E. et al. Lymph node colonization induces tumor-immune tolerance to promote distant metastasis. Cell 185, 1924–1942 e23 (2022).

Zhou, H. et al. Cancer immunotherapy responses persist after lymph node resection. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.09.19.558262 (2023).

Karakousi, T., Mudianto, T. & Lund, A. W. Lymphatic vessels in the age of cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 24, 363–381 (2024).

Delclaux, I., Ventre, K. S., Jones, D. & Lund, A. W. The tumor-draining lymph node as a reservoir for systemic immune surveillance. Trends Cancer 10, 28–37 (2023).

Forde, P. M. et al. Neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade in resectable lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 378, 1976–1986 (2018).

Deng, H. et al. Impact of lymphadenectomy extent on immunotherapy efficacy in postresectional recurred non-small cell lung cancer: a multi-institutional retrospective cohort study. Int. J. Surg. 110, 238–252 (2024).

Spitzer, M. H. et al. Systemic immunity is required for effective cancer immunotherapy. Cell 168, 487–502 e415 (2017).

Fransen, M. F. et al. Tumor-draining lymph nodes are pivotal in PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint therapy. JCI Insight 3, e124507 (2018).

Prokhnevska, N. et al. CD8+ T cell activation in cancer comprises an initial activation phase in lymph nodes followed by effector differentiation within the tumor. Immunity 56, 107–124 e105 (2023).

Baluk, P. et al. Functionally specialized junctions between endothelial cells of lymphatic vessels. J. Exp. Med. 204, 2349–2362 (2007).

Thorup, L., Hjortdal, A., Boedtkjer, D. B., Thomsen, M. B. & Hjortdal, V. The transport function of the human lymphatic system—a systematic review. Physiol. Rep. 11, e15697 (2023).

Blatter, C. et al. In vivo label-free measurement of lymph flow velocity and volumetric flow rates using Doppler optical coherence tomography. Sci. Rep. 6, 29035 (2016).

Bouta, E. M. et al. In vivo quantification of lymph viscosity and pressure in lymphatic vessels and draining lymph nodes of arthritic joints in mice. J. Physiol. 592, 1213–1223 (2014).

Kwon, S. & Sevick-Muraca, E. M. Noninvasive quantitative imaging of lymph function in mice. Lymphat. Res. Biol. 5, 219–231 (2007).

Santambrogio, L. Immunology of The Lymphatic System 1st edn, Vol. 5 (Springer, 2013).

Hall, J. & Hall, M. E. in Guyton and Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology 14th edn (Elsevier, 2021).

Kawashima, Y., Sugimura, M., Hwang, Y. & Kudo, N. The lymph system in mice. Jpn J. Vet. Res. 12, 69–78 (1964).

Van den Broeck, W., Derore, A. & Simoens, P. Anatomy and nomenclature of murine lymph nodes: descriptive study and nomenclatory standardization in BALB/cAnNCrl mice. J. Immunol. Methods 312, 12–19 (2006).

Ubellacker, J. M. et al. Lymph protects metastasizing melanoma cells from ferroptosis. Nature 585, 113–118 (2020).

Devilbiss, A. W. et al. Metabolomic profiling of rare cell populations isolated by flow cytometry from tissues. eLife 10, e61980 (2021).

Shrewsbury, M. M. Thoracic duct lymph in unanesthetized mouse: method of collection, rate of flow and cell content. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 101, 492–494 (1959).

Gesner, B. M. & Gowans, J. L. The output of lymphocytes from the thoracic duct of unanaesthetized mice. Br. J. Exp. Pathol. 43, 424–430 (1962).

Nagahashi, M. et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate in the lymphatic fluid determined by novel methods. Heliyon 2, e00219 (2016).

Zawieja, D. C. et al. Lymphatic cannulation for lymph sampling and molecular delivery. J. Immunol. 203, 2339–2350 (2019).

Percie du Sert, N. et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: updated guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 18, e3000410 (2020).

Smith, A. J., Clutton, R. E., Lilley, E., Hansen, K. E. A. & Brattelid, T. PREPARE: guidelines for planning animal research and testing. Lab Anim. 52, 135–141 (2018).

De Vleeschauwer, S. I. et al. OBSERVE: guidelines for the refinement of rodent cancer models. Nat. Protoc. 19, 2571–2596 (2024).

Festing, M. F. & Altman, D. G. Guidelines for the design and statistical analysis of experiments using laboratory animals. ILAR J. 43, 244–258 (2002).

Dell, R. B., Holleran, S. & Ramakrishnan, R. Sample size determination. ILAR J. 43, 207–213 (2002).

Zolla, V. et al. Aging-related anatomical and biochemical changes in lymphatic collectors impair lymph transport, fluid homeostasis, and pathogen clearance. Aging Cell 14, 582–594 (2015).

Fraser, R., Cliff, W. J. & Courtice, F. C. The effect of dietary fat load on the size and composition of chylomicrons in thoracic duct lymph. Q. J. Exp. Physiol. Cogn. Med. Sci. 53, 390–398 (1968).

Ikeda, I., Tomari, Y. & Sugano, M. Interrelated effects of dietary fiber and fat on lymphatic cholesterol and triglyceride absorption in rats. J. Nutr. 119, 1383–1387 (1989).

Feldman, E. B. et al. Dietary saturated fatty acid content affects lymph lipoproteins: studies in the rat. J. Lipid Res. 24, 967–976 (1983).

Cifarelli, V. & Eichmann, A. The intestinal lymphatic system: functions and metabolic implications. Cell Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 7, 503–513 (2019).

Hablitz, L. M. et al. Circadian control of brain glymphatic and lymphatic fluid flow. Nat. Commun. 11, 4411 (2020).

Dakup, P. P., Porter, K. I., Little, A. A., Zhang, H. & Gaddameedhi, S. Sex differences in the association between tumor growth and T cell response in a melanoma mouse model. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 69, 2157–2162 (2020).

Miller, L. R. et al. Considering sex as a biological variable in preclinical research. FASEB J. 31, 29–34 (2017).

Zuurbier, C. J., Koeman, A., Houten, S. M., Hollmann, M. W. & Florijn, W. J. Optimizing anesthetic regimen for surgery in mice through minimization of hemodynamic, metabolic, and inflammatory perturbations. Exp. Biol. Med. 239, 737–746 (2014).

Bachmann, S. B., Proulx, S. T., He, Y., Ries, M. & Detmar, M. Differential effects of anaesthesia on the contractility of lymphatic vessels in vivo. J. Physiol. 597, 2841–2852 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank T. P. Padera for insightful review and suggestions, which greatly improved the manuscript text. This work was supported by funding from the Breast Cancer Alliance Young Investigator Award, NIH/NCI 1R01CA282202, DF/HCC Incubator Award sponsored by the Ludwig Center at Harvard and the Melanoma Research Foundation Career Development Award.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.S. and J.M.U. conceived the protocol. M.S. developed the lymph collection from cisterna chyli procedure. M.S. and J.M.U. developed the isolation of cancer cells from lymph procedure. A.S. and S.T. provided expertise and technical support for lymph collection. P.L., H.Z., M.O., L.M., and S.M. provided conceptual support and input on the manuscript content. J.M.U. provided anticipated results. M.S. and J.M.U. wrote the manuscript. All authors read and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics

All experiments were conducted in compliance with the approved Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health IACUC protocol IS00003460, and proper permission was granted for the publication of the included videos and images.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Protocols thanks Nathan Reticker-Flynn and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Key reference

Ubellacker, J. M. et al. Lymph protects metastasizing melanoma cells from ferroptosis. Nature 585, 113–118 (2020): https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2623-z

Supplementary information

Supplementary Video 1

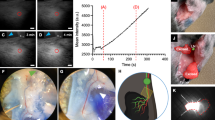

Lymph collection from the cisterna chyli. The cisterna chyli is dried using a gauze pad and a cotton swab. Then, a glass cannula (attached to the 1 mL syringe/Luer/tubing apparatus, Fig. 2b) is slowly inserted into cisterna chyli. Lymph fluid is collected within the glass cannula by capillary action and gentle aspiration. The collected lymph is transferred into a cold 0.2 mL microcentrifuge tube. The cannula is inserted twice again to recover the entire lymph fluid coming out from the cisterna chyli and the lymph is transferred into the same cold 0.2 mL microcentrifuge tube.

Supplementary Video 2

Visualization of the tumor-draining lymphatics. The focus is made on the cranial section of the subcutaneous B16 melanoma tumor from a C57BL/6J female mouse. The tumor-draining blood vessel that goes from the tumor to the axillary region is identified. The tumor-training lymph vessel is commonly located close to the tumor-draining blood vessel and can be differentiated by is white/translucent color. A snapshot highlighting in yellow both the tumor-draining blood and lymph vessels appears at t = 18 s and is represented in Fig. 5d.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Sabatier, M., Solanki, A., Thangaswamy, S. et al. Lymphatic collection and cell isolation from mouse models for multiomic profiling. Nat Protoc 20, 884–901 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41596-024-01081-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41596-024-01081-0