Abstract

Electron spin resonance coupled with uranium-series dating (ESR/U-series) of carbonate hydroxyapatite in tooth enamel is the main technique used to obtain age determinations from Pleistocene fossils beyond the range of radiocarbon dating. This chronological information allows to better understand diachronic change in the palaeontological record, especially with regard to the evolution of the genus Homo. Given the relative paucity of human teeth at palaeontological and archaeological localities, ESR/U-series is widely applied to the teeth of ungulate species. However, the accuracy of ESR/U-series ages is greatly affected by the incorporation of uranium in the enamel during burial in sediments. It has been shown that uranium content is positively correlated with an increased degree of atomic order in carbonate hydroxyapatite crystals, the latter determined using infrared spectroscopy. Here we present a reference infrared spectral library of tooth enamel from African ungulates, based on the grinding curve method, which serves as baseline to track the diagenetic history of carbonate hydroxyapatite in different species and thus select the best-preserved specimens for dating.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

A large portion of the evolutionary history of the genus Homo and our species Homo sapiens is based on the Pleistocene (2.588-0.012 Ma) palaeontological record of Africa1,2. Our ability to understand diachronic change during this geological epoch relies on the application of dating methods that can provide absolute age determinations for human fossils. For periods older than ~50,000 years ago, which is the limit of radiocarbon dating, electron spin resonance coupled with uranium-series dating (ESR/U-series) of carbonate hydroxyapatite in tooth enamel is the only method that can provide accurate ages directly from fossils3,4.

ESR is a trapped-charge dating method based on the capacity of some minerals (e.g., carbonate hydroxyapatite and quartz) to store the energy coming from radiations emitted in the environment around the sample (i.e., produced from the radioactive decay in sediments and from cosmic rays) and in some cases in the sample itself (e.g., dental tissues that incorporate uranium during burial). The amount of energy absorbed by the sample, or “dose”, is a function of the radioactivity and the burial time. This allows using this phenomenon for dating: an age can be determined by dividing the dose absorbed by the sample (called the equivalent dose and measured in Gray, Gy) by the amount of energy emitted per year (the dose rate, measured in Gray per year, Gy·a−1). For fossil teeth, the enamel is targeted for ESR dating because it is the most mineralised dental tissue (~96% of hydroxyapatite in enamel versus ~70% in dentine) and the most crystalline. However, the uptake of trace elements such as uranium (U) in the dental tissues during burial in sediments, as a consequence of diagenesis, contributes to the dose rate and needs to be accounted for, hence the combination of ESR with uranium-series dating. U-series (230Th/U) is based on the radioactive decay of 234U to 230Th within the 238U decay chain5,6. A U-series age is obtained using the decay constants of the isotopes of interest as well as the 234U/238U and 230Th/238U ratios. The method is commonly used on speleothems, which incorporate U during the nucleation of the crystals (under the form of calcite or aragonite). In teeth, the application of U-series provides a minimum estimate in the best case, i.e., if no loss of U (“leaching”) occurred during burial, since the time between the burial of the tooth and the uptake of U is unknown. To overcome the difficulties related to the use of these two dating methods, it was proposed to combine ESR with U-series to reconstruct the U uptake mode in the dental tissues and derive the dose rate7. Nevertheless, U leaching remains a serious issue since part of the information needed to reconstruct the kinetics of U in the dental tissues is missing, hindering a precise reconstruction of the dose rate and hence the calculation of accurate ages. Ideally, one would date teeth with little U (i.e., a few hundred ppb) since such levels of U in the dental tissues do not impact significantly the dose rate8.

Depending on parameters such as the sedimentological context, the state of preservation, and the age of the sample, the U-content varies greatly from one site to the other, and even within the same site or sediment layer9. During burial in sediments and at pH values < 8, carbonate hydroxyapatite crystals in tooth enamel tend to become larger and more ordered at the atomic level according to Ostwald ripening, as a consequence of diagenetic processes involving the dissolution and reprecipitation of crystals. The latter entails the incorporation of uranium from sediment, as well as its leaching, and translates into an increased degree of atomic order, broadly defined here as crystallinity, in the carbonate hydroxyapatite crystals10. Therefore, characterising the integrity of enamel samples prior to dating is a fundamental step in order to select the best-preserved teeth, namely those with low U-content. Several studies have shown the effectiveness of Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) in determining the degree of atomic order of carbonate hydroxyapatite crystals in enamel, dentine, cementum, and bone using the grinding curve method in transmission mode11,12,13. This method allows decoupling the opposite effects of particle size and degree of atomic order on the shape of infrared spectra by plotting the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the ν3 band of phosphates (1034 cm−1) and the infrared splitting factor (IRSF) of the ν4 band of phosphates (peaks at 604 and 565 cm−1) upon repeated grinding of the same potassium bromide (KBr) pellet. Using the grinding curves, it has recently been shown that an increase of atomic order is positively correlated with higher U-content (several ppm of U)9,14. The FTIR grinding curves thus represent a rapid pre-screening method to select the best-preserved samples, which are less likely to be affected by uranium leaching.

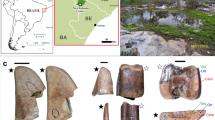

While teeth are partially destructed when applying standard protocols similar to the one used in this study, technical developments and methodological improvements allowed limiting the damages on human teeth to be dated using ESR/U-series15,16,17. However, considering the relative scarcity of human teeth in the palaeontological record and their value for palaeoanthropology, other mammals associated with human activities or with human presence in the landscape and at archaeological sites are usually targeted for ESR/U-series dating8,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25. These include mainly ungulates, which occur in large populations across Africa and constitute the bulk of classification systems aimed at describing the evolutionary history of mammals (e.g., land mammal ages)26,27, and whose teeth exhibit thicker enamel. As shown in an earlier study12, the degree of crystallinity of carbonate hydroxyapatite in fresh tooth enamel changes based on the species, thus yielding different FTIR grinding curves. Therefore, in order to apply the grinding curve method to fossil ungulate teeth potentially suitable for ESR/U-series dating, a baseline should be created that accounts for the varying degrees of crystallinity in different ungulate species. Here we present a database of FTIR spectra of ungulate species from southern Africa that were used to create reference grinding curves to assess the crystallinity of fossil specimens of unknown state of preservation (Fig. 1). This information can be used to select the best-preserved specimens for ESR/U-series dating, thus minimising the risk of incurring in samples affected by uranium leaching. This database includes mainly bovids ranging from small to large body size, as well as species from other important families found in Pleistocene assemblages. The grinding curve plot shows clear differences in enamel carbonate hydroxyapatite crystallinity between species and across families. Our aim is to provide an open-access spectral library and grinding curve reference plot that can be used to improve the accuracy of ESR/U-series dates on ungulate teeth. The same dataset may find application also in the analysis of carbon and oxygen stable isotopes for palaeoenvironmental reconstructions, which may be affected by diagenetic processes.

Methods

Teeth were obtained from the collection of modern vertebrates of the National Museum Bloemfontein (South Africa), stored at the Florisbad Quaternary Research Station. All specimens are permanent and fully erupted and derive from adult individuals that lived in South African populations. No selection was made based on tooth type or position in the oral cavity, since it was demonstrated that tooth enamel crystallinity is not affected by these parameters12. Similarly, it was demonstrated that there is no intra-species variability12. However, we focused on premolars and molars. Sample collection targeted the ungulate species that are more often found in the archaeological and palaeontological record and/or are the nearest extant parallel to extinct species within the same genus: for instance, Antidorcas bondi (extinct Bond’s springbok) and Antidorcas marsupialis (extant springbok); Damaliscus niro (extinct species of blesbok) and Damaliscus pygargus (extant blesbok); Hippopotamus gorgops (extinct giant hippopotamus) and Hippopotamus amphibius (extant hippopotamus)9,14,28,29,30,31. These are among the species that are more likely to be selected for ESR/U-series dating.

A total of 15 species were sampled, which are listed in Table 1. One tooth was selected for each species and one enamel fragment was removed from each tooth, which provided the powder necessary for FTIR analyses. Enamel was separated from dentine using a diamond saw and cleaned using a rotary drill bit coated with diamond grit. Enamel fragments were crushed in an agate mortar and pestle and the resulting powder was sieved through a 200 µm mesh to obtain a homogeneous particle size.

FTIR spectra were acquired using the grinding curve method. About 5 mg of sample powder and 20 mg of FTIR-grade KBr (Sigma-Aldrich) were placed in an agate mortar and pestle and lightly ground. The mixture was transferred to a pellet die and pressed by applying 2 tons using a benchtop mini-press (Specac). The pellet was then analysed in transmission mode using a Thermo Scientific Nicolet iS5 infrared spectrometer equipped with an iD1 transmission module and a deuterated triglycine sulphate (DTGS) detector. Spectra were collected in the 4000-400 cm−1 spectral region at 4 cm−1 resolution and in 32 scans, and processed using OMNIC v. 9.13. The FWHM of the phosphate ν3 band (1034 cm−1) and the IRSF of the phosphate ν4 band (604 and 565 cm−1) in carbonate hydroxyapatite were calculated using Macros Basic v. 10 and according to standard literature12,32. The baseline for the calculation of the ν3 intensity was drawn between 2000 and 400 cm−1, whereas the baseline for the calculation of the intensity of the two peaks in the ν4 band was drawn between 820 and 400 cm−1. After processing the spectrum, the pellet was removed from the instrument and half of it was ground more vigorously in order to reduce particle size. The other half was discarded prior to grinding to avoid overloading of the infrared spectrum caused by increased absorption promoted by the larger overall surface area of the particles. After adding 10 mg of KBr, a second pellet was prepared and analysed following the procedure described above. The same operation was repeated a third time by grinding half of the second pellet with even more strength. The FWHM and IRSF values of carbonate hydroxyapatite for each grinding were plotted to obtain a trendline, or grinding curve. Four additional replicates were produced using enamel powder from the same tooth, for a total of five grinding curves for each ungulate species. Considering the subjective nature of the grinding process, the same operator should perform all of the grindings of a given curve.

Data Records

The infrared spectra used for establishing grinding curves are located in an online repository (“Enamel_African_ungulates.zip”)33 in a folder of raw spectra (“FTIR spectra”) together with a separate file including the FWHM and IRSF values for each spectrum and a plot showing the grinding curves of each ungulate species (“Enamel_grinding_curves.xslx”) (Fig. 2), and the macro file used to calculate the FWHM and IRSF values (“IRSF_FWHM.mac”). The library includes 225 infrared spectra in “.spa” and “.csv” formats (total: 450 files), which can be read by spectroscopy programmes. Spectra are named with progressive numbers in order to distinguish replicates and number of grindings; for instance, “Giraffe2_03” indicates the third grinding of the second grinding curve of giraffe enamel. The same naming system is followed in the grinding curve file.

Technical Validation

At the spectroscopic level, the grinding curve method allows detecting differences in atomic order in different samples independently from particle size, since FWHM and IRSF are calculated over a range of particle sizes. This makes it unnecessary to standardise the initial amount of sample and KBr, the degree of grinding, and the amount of pressure applied to the mixture to obtain a pellet. While we used a press equipped with a gauge that provides a measure of the applied pressure, equivalent results can be achieved with a hand press; in both cases the same operator should perform all of the grindings of a given curve to ensure that each successive grinding is performed more vigorously than the previous one.

An earlier study12 on human, horse, cow, and dog enamel used the least squares method to fit the grinding curve data, showing that the correlation coefficient (R2) of FWHM and IRSF is always above 0.9. R2 values above 0.9 can be observed in the library presented herein (Table 2), thus validating the technical quality of the grinding curves. Similar results have been obtained by applying the grinding curve method to calcite34 and aragonite35.

Recent studies have used the grinding curve of present-day A. marsupialis enamel as reference for fossil teeth of small-sized Antilopinae, most likely the extinct species A. bondi, recovered at the Late Pleistocene archaeological site of Lovedale (South Africa), dated to 77–56 ka9,14,36. The enamel in the fossil specimens showed varying degrees of crystallinity, based on the offset of the grinding curves with the reference curve of A. marsupialis, which positively correlated with the amount of uranium incorporated as a result of diagenetic alteration during burial in sediments. The most crystalline samples, i.e. the samples exhibiting the largest offset compared to the reference curve, were also the richest in uranium, whereas samples with intermediate uranium contents exhibited grinding curves located between modern reference and extensively recrystallised specimens (Fig. 3). Therefore, the grinding curve method of tooth enamel can be used as a screening tool to select the least crystalline (i.e., best-preserved) specimens for ESR/U-series dating, and thus avoid materials with high U-content or that suffered from uranium leaching.

Grinding curves of fossil teeth from Lovedale (South Africa) compared to a reference curve of springbok (dashed line). The three most recrystallised specimens, which exhibit greater curve offset compared to the springbok curve, are also the richest in uranium (ranging from 9.7 to 29.6 ppm). All other specimens are characterised by amounts of uranium ranging from 1.7 to 5.8 ppm (data from Richard et al.9,14).

Usage Notes

This reference library of infrared spectra and related grinding curve plot can be used to determine the degree of crystallinity of enamel carbonate hydroxyapatite in teeth of unknown state of preservation from the same species analysed in this study. The plot will be most useful with regard to the African continent, but may provide support also with closely related species from Asia and Europe (e.g., other taxa within the Bovinae subfamily, Bovini tribe). The chart can be used to display only specific taxa, which are relevant to the research question. To determine the crystallinity of a tooth of unknown preservation, users should develop a grinding curve by plotting the FWHM and IRSF values of each FTIR spectrum obtained from the enamel. The offset between this curve and the reference curve will provide an assessment of the degree of crystallinity of the tooth. If the curves overlap, the fossil tooth is well preserved. If an offset exists, then the fossil tooth underwent diagenetic alteration and should not have priority for ESR/U-series dating.

This method will yield best results if applied systematically to all the teeth from a given assemblage (e.g., same fossil/archaeological site) in order to track diagenetic processes in three dimensions throughout the depositional contexts, especially when paired with the characterisation of the sedimentary matrix by FTIR spectroscopy37,38,39,40. FTIR micro-spectroscopy41,42, Raman hyperspectral imaging43, and laser-induced fluorescence9 may provide additional information about the state of preservation of the specimens and help select specific regions of interest in the enamel. Obviously, adding more species to the library will help expand the references and make comparisons with unknown samples more accurate. In addition, the library may be used to assess the crystallinity of enamel in relation to the analysis of carbon and oxygen stable isotopes, which are important parameters in palaeoecological studies44. While there are no studies linking diagenetic alteration as determined with FTIR grinding curves with significant deviations in δ13C and δ18O values, the fact that the uranium content of enamel undergoes important changes with diagenesis may imply that deviations are large also for carbon and oxygen, which are among the main components of carbonate hydroxyapatite. Scanning electron microscopy combined with FTIR micro-spectroscopy and electron microprobe analysis of fossil teeth characterised by extensive recrystallisation seem to point in this direction42.

Code availability

The macro used to calculate the FWHM of the ν3 band and the IRSF of the ν4 band of phosphates runs in Macros Basic coupled with OMNIC (including versions of the software older than the one used in this study) and it is available in the online repository33 with the raw spectra (“IRSF_FWHM.mac”). Given the simple nature of the calculations, similar macros can be easily developed using different spectroscopy programmes.

References

Grün, R. & Stringer, C. Direct dating of human fossils and the ever-changing story of human evolution. Quaternary Science Reviews 322, 108379, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2023.108379 (2023).

Grine, F. E. in Africa from MIS 6-2 (eds Jones, S. C. & Stewart, B. A.) 323–382 (Springer, 2016).

Richard, M. in Handbook of Archaeological Sciences 69–87 (2023).

Ikeya, M. New applications of electron spin resonance: dating, dosimetry and microscopy. (World Scientific, 1993).

Pons-Branchu, E. in Handbook of Archaeological Sciences 89–97 (2023).

Ivanovich, M. & Harmon, R. S. Uranium-series disequilibrium: applications to earth, marine, and environmental sciences. 2nd edn, (Clarendon Press, 1992).

Grün, R., Schwarcz, H. P. & Chadam, J. ESR dating of tooth enamel: Coupled correction for U-uptake and U-series disequilibrium. International Journal of Radiation Applications and Instrumentation. Part D. Nuclear Tracks and Radiation Measurements 14, 237–241, https://doi.org/10.1016/1359-0189(88)90071-4 (1988).

Richard, M. et al. New electron spin resonance (ESR) ages from Geißenklösterle Cave: A chronological study of the Middle and early Upper Paleolithic layers. Journal of Human Evolution 133, 133–145, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2019.05.014 (2019).

Richard, M. et al. Investigating the effect of diagenesis on ESR dating of Middle Stone Age tooth samples from the open-air site of Lovedale, Free State, South Africa. Quaternary Geochronology 69, 101269, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quageo.2022.101269 (2022).

Weiner, S. Microarchaeology. Beyond the Visible Archaeological Record. (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Dal Sasso, G., Asscher, Y., Angelini, I., Nodari, L. & Artioli, G. A universal curve of apatite crystallinity for the assessment of bone integrity and preservation. Scientific Reports 8, 12025, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-30642-z (2018).

Asscher, Y., Weiner, S. & Boaretto, E. Variations in Atomic Disorder in Biogenic Carbonate Hydroxyapatite Using the Infrared Spectrum Grinding Curve Method. Advanced Functional Materials 21, 3308–3313, https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201100266 (2011).

Asscher, Y., Regev, L., Weiner, S. & Boaretto, E. Atomic Disorder in Fossil Tooth and Bone Mineral: An FTIR Study Using the Grinding Curve Method. ArcheoSciences 35, 135–141, https://doi.org/10.4000/archeosciences.3062 (2011).

Richard, M. et al. New ESR dates from Lovedale, Free State, South Africa: implications for the study of tooth diagenesis. South African Archaeological Bulletin 78, 95–103, https://cnrs.hal.science/hal-04378183/file/RICHARD%20et%20al._2023_SAAB.pdf (2023).

Duval, M. et al. The first direct ESR dating of a hominin tooth from Atapuerca Gran Dolina TD-6 (Spain) supports the antiquity of Homo antecessor. Quaternary Geochronology 47, 120–137, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quageo.2018.05.001 (2018).

Joannes-Boyau, R. Detailed protocol for an accurate non-destructive direct dating of tooth enamel fragment using Electron Spin Resonance. Geochronometria 40, 322–333, https://doi.org/10.2478/s13386-013-0132-7 (2013).

Grün, R. Semi non-destructive, single aliquot ESR dating. Ancient TL 13, 7 (1995).

Grün, R. et al. Direct dating of Florisbad hominid. Nature 382, 500–501, https://doi.org/10.1038/382500a0 (1996).

Grün, R. & Beaumont, P. Border Cave revisited: a revised ESR chronology. Journal of Human Evolution 40, 467–482, https://doi.org/10.1006/jhev.2001.0471 (2001).

Val, A. et al. The place beyond the trees: renewed excavations of the Middle Stone Age deposits at Olieboomspoort in the Waterberg Mountains of the South African Savanna Biome. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 13, 116, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-021-01302-7 (2021).

Richard, M. et al. Contribution of ESR/U-series dating to the chronology of late Middle Palaeolithic sites in the middle Rhône valley, southeastern France. Quaternary Geochronology 30, 529–534, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quageo.2015.06.002 (2015).

Richard, M. et al. ESR/U-series chronology of early Neanderthal occupations at Cova Negra (Valencia, Spain). Quaternary Geochronology 49, 283–290, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quageo.2018.05.004 (2019).

Falguères, C. et al. ESR/U-series dates on Equus teeth from the Middle Pleistocene Acheulean site of Cueva del Angel, Spain. Quaternary Geochronology 49, 297–302, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quageo.2018.02.003 (2019).

Bahain, J.-J. et al. ESR/U-series dating of faunal remains from the paleoanthropological site of Biache-Saint-Vaast (Pas-de-Calais, France). Quaternary Geochronology 30, 541–546, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quageo.2015.02.020 (2015).

Duval, M. et al. On the limits of using combined U-series/ESR method to date fossil teeth from two Early Pleistocene archaeological sites of the Orce area (Guadix-Baza basin, Spain). Quaternary Research 77, 482–491, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yqres.2012.01.003 (2017).

Van Couvering, J. A. & Delson, E. African Land Mammal Ages. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 40, e1803340, https://doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2020.1803340 (2020).

Brink, J. S. in Quaternary Environmental Change in Southern Africa: Physical and Human Dimensions (eds Knight, J. & Grab, S. W.) 284–305 (Cambridge University Press, 2016).

Codron, D., Brink, J. S., Rossouw, L. & Clauss, M. The evolution of ecological specialization in southern African ungulates: competition- or physical environmental turnover? Oikos 117, 344–353, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2007.0030-1299.16387.x (2008).

Brink, J. S. & Lee-Thorp, J. A. The feeding niche of an extinct springbok, Antidorcas bondi (Antelopini, Bovidae), and its palaeoenvironmental meaning. South African Journal of Science 88, 227–229, https://hdl.handle.net/10520/AJA00382353_9466 (1992).

Brink, J. S. The archaeozoology of Florisbad, Orange Free State. Memoirs van die Nasionale Museum, Bloemfontein 24, 1–151 (1987).

Brink, J. S. et al. First hominine remains from a ~1.0 million year old bone bed at Cornelia-Uitzoek, Free State Province, South Africa. Journal of Human Evolution 63, 527–535, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2012.06.004 (2012).

Weiner, S. & Bar-Yosef, O. States of Preservation of Bones from Prehistoric Sites in the Near East: A Survey. Journal of Archaeological Science 17, 187–196, https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-4403(90)90058-D (1990).

Toffolo, M. Enamel African ungulates. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10980093 (2024).

Regev, L., Poduska, K. M., Addadi, L., Weiner, S. & Boaretto, E. Distinguishing between calcites formed by different mechanisms using infrared spectrometry: archaeological applications. Journal of Archaeological Science 37, 3022–3029, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2010.06.027 (2010).

Toffolo, M. B., Regev, L., Dubernet, S., Lefrais, Y. & Boaretto, E. FTIR-Based Crystallinity Assessment of Aragonite–Calcite Mixtures in Archaeological Lime Binders Altered by Diagenesis. Minerals 9, 121, https://doi.org/10.3390/min9020121 (2019).

Wroth, K. et al. Human occupation of the semi-arid grasslands of South Africa during MIS 4: New archaeological and paleoecological evidence from Lovedale, Free State. Quaternary Science Reviews 283, 107455, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2022.107455 (2022).

Rink, W. J. et al. Age of the Mousterian industry at Hayonim Cave, Northern Israel, using electron spin resonance and 230Th/234U methods. Journal of Archaeological Science 31, 953–964, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2003.12.009 (2004).

Weiner, S., Goldberg, P. & Bar-Yosef, O. Three-dimensional Distribution of Minerals in the Sediments of Hayonim Cave, Israel: Diagenetic Processes and Archaeological Implications. Journal of Archaeological Science 29, 1289–1308, https://doi.org/10.1006/jasc.2001.0790 (2002).

Mercier, N. et al. Thermoluminescence Dating and the Problem of Geochemical Evolution of Sediments – A Case Study: The Mousterian Levels at Hayonim. Israel Journal of Chemistry 35, 137–141, https://doi.org/10.1002/ijch.199500021 (1995).

Karkanas, P., Bar-Yosef, O., Goldberg, P. & Weiner, S. Diagenesis in Prehistoric Caves: the Use of Minerals that Form In Situ to Assess the Completeness of the Archaeological Record. Journal of Archaeological Science 27, 915–929, https://doi.org/10.1006/jasc.1999.0506 (2000).

Lebon, M., Zazzo, A. & Reiche, I. Screening in situ bone and teeth preservation by ATR-FTIR mapping. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 416, 110–119, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2014.08.001 (2014).

Dauphin, Y. et al. Diagenetic alterations of Meriones incisors (Rodentia) of El Harhoura 2 cave, Morocco (late Pleistocene–middle Holocene). PalZ 92, 163–177, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12542-017-0382-4 (2018).

Dal Sasso, G., Angelini, I., Maritan, L. & Artioli, G. Raman hyperspectral imaging as an effective and highly informative tool to study the diagenetic alteration of fossil bones. Talanta 179, 167–176, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.talanta.2017.10.059 (2018).

Sponheimer, M. & Lee-Thorp, J. A. Alteration of Enamel Carbonate Environments during Fossilization. Journal of Archaeological Science 26, 143–150, https://doi.org/10.1006/jasc.1998.0293 (1999).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the European Union (ERC, PEOLE, project n. 101039711 to Michael Toffolo). Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them. Michael Toffolo is supported also by the grant RYC2021-030917-I funded by the MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by the “European Union NextGenerationEU/PRTR”. The authors wish to thank Lloyd Rossouw and the National Museum Bloemfontein for kindly providing access to the specimens, and Sharon Holt for help sorting through the collections.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.B.T. and M.R. designed the study, collected the specimens, analysed the data, compiled the dataset, and wrote the manuscript. M.R. prepared the specimens. M.B.T. performed infrared spectroscopy.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Toffolo, M.B., Richard, M. Infrared spectral library of tooth enamel from African ungulates for accurate electron spin resonance dating. Sci Data 11, 890 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03725-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03725-y