Abstract

The mariculture industry has seen a rapid expansion in recent years due to the increasing global demand for seafood. However, the industry faces challenges from climate change and increased pathogen pressure. Additionally, the chemicals used to enhance mariculture productivity are changing ocean ecosystems. This study analyzed 36 surface-water metagenomes from South Korean mussel, oyster, scallop, and shrimp farms to expand our understanding of aquaculture microbial genetic resources and the potential impacts of these anthropogenic inputs. We recovered 240 non-redundant species-level metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs), comprising 224 bacteria, 13 archaea, and three eukaryotes. Most MAGs were assigned to Proteobacteria, Bacteroidota, and Actinobacteriota, with 40.7% remaining unclassified at the species level. Among the three eukaryotic MAGs, one was identified as a novel lineage of green algae, highlighting the uncharacterized genetic diversity in mariculture environments. Additionally, 22 prokaryotic MAGs harbored 26 antibiotic and metal resistance genes, with MAGs carrying beta-lactamases being particularly prevalent in most farms. The obtained microbiome data from mariculture environments can be utilized in future studies to foster healthy, sustainable mariculture practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Mariculture plays a crucial role in the world’s food supply1. However, the industry faces significant challenges from climate change and increased pathogen pressure, which lead to production losses, health risks, and severe economic crises2. Although antibiotics and other chemical products have been used to enhance mariculture yields3,4,5, they tend to accumulate in living organisms and the environment, raising global concerns6,7,8. These anthropogenic inputs also impact the environmental microbiome surrounding mariculture, which in turn can affect farmed organisms from a holobiont perspective9,10,11. Additionally, changes in microbial community structure and functional genes due to these inputs have been linked to alterations in global biogeochemical cycles and biological phenomena such as algal blooms, which greatly affect ecosystems12,13. Therefore, a better understanding of the microbial ecology of mariculture is crucial.

Recent advancements in mariculture have increased the consumption of raw fish and shellfish, posing potential health risks14 due to bacterial infections from Vibrio and Salmonella15, toxin-producing dinoflagellate16, and norovirus17. Moreover, anthropogenic impacts, including the use of antibiotics in mariculture, can lead to the emergence and spread of antibiotic-resistance genes (ARGs), posing a threat to human health from a one-health perspective18,19,20. While most metagenomic studies on mariculture environments have focused on the emergence and spread of opportunistic pathogens and ARGs, few efforts have been made to recover genomes for impact assessment. Advances in sequencing technologies and metagenomic binning approaches have improved our understanding of unknown taxa, enabling the study of their function, diversity, and ecology using genome-centric strategies21. However, although these breakthroughs have enhanced our knowledge of ocean ecosystem biodiversity22,23, our understanding of the microbial ecology of mariculture, especially the influence of co-existing farmed organisms, remains limited. Therefore, this study sought to characterize the microbial genetic resources in mussel, oyster, scallop, and shrimp farms in South Korea.

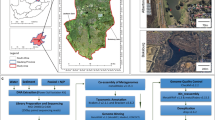

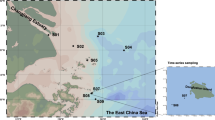

The dataset used in this study consisted of 36 samples from five farms: 28 newly collected surface-water metagenomes from oyster, scallop, and mussel mariculture, and eight samples from a previous shrimp farm study24 (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 1). A total of 437.3 gigabases (Gb) of metagenomic data were sequenced at an average depth of 12.1 Gb per sample, yielding 434.6 Gb and 2.9 billion high-quality reads after quality control (Supplementary Table 2). From these data, we recovered more than 612 medium-quality metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs)25 from an initial 3,397 bins using MetaBAT2. Subsequently, 240 of these MAGs were classified at the non-redundant species level (average nucleotide identity (ANI) 95%). Species-level MAGs had an average completeness of 82.7% (±12.7) and a contamination rate of 1.5% (±1.5). Among these MAGs, 224 were classified as bacteria, 13 as archaea, and three as eukaryotes (Supplementary Table 3).

Overall research scheme. (A) Map of sampling sites, with each color representing a different aquaculture organism. The sampling year and the number of sampling sites are indicated in the figure. Detailed locations for the sites marked with the circled A and B are provided in Supplementary Table 1. (B) Schematic of the data processing workflow from sampling to genome-centric metagenomics. More details are provided in the Methods.

For the prokaryotic MAGs, 38.3% MAGs (91 species) were high quality (HQ; completion > 90% and contamination < 5%), and 61.6% (146 species) were of medium quality (completion > 50% and contamination ≤ 10%). According to the MIMAG standard, there were only six HQ MAGs with full-length 23 S, 16 S, and 5 S rRNA genes and > 18 tRNAs, and an additional four HQ MAGs with partial 16 S, 23 S, and 5 S rRNAs. Most MAGs were assigned to Proteobacteria (n = 110 [Alphaproteobacteria, n = 39; and Gammaproteobacteria, n = 71]), Bacteroidota (n = 62), and Actinobacteriota (n = 23) (Fig. 2). Although 93.7% of MAGs could be classified to the genus level, 40.7% remained unclassified at the species level, indicating that this dataset mainly comprises novel species.

Phylogenetic tree and sample distribution of prokaryotic MAGs. (A) A total of 237 prokaryotic MAGs were obtained in this study. Each row of the heatmap outside the tree represents a different aquaculture organism. The color of the filled circles on the tree indicates the phylum of each MAG. (B) Scatter plot of prokaryotic MAG quality, with high-quality MAGs highlighted in the red box. (C) UpSet plot showing the distribution of MAGs across four aquacultures and phyla.

Following de-duplication at an ANI threshold of 95%, the fourteen eukaryotic MAGs were reduced to three distinct, non-redundant MAGs. The eukaryotic MAGs demonstrated satisfactory quality metrics, with an average size of 14.1 megabases, an N50 value of 25 kilobase pairs, 94.9% (±2.9) completeness, and 1.59% (±3.0) contamination. These MAGs were classified into the Ostreococcus (n = 2) and Micromonas (n = 1) genera, both of which represent green algae belonging to the order Mamiellales, as determined by phylogenetic analyses utilizing the RNA polymerase database from the Tara Oceans project (Fig. 3). As of April 1, 2024, there were 25 and 35 genomes of Ostreococcus and Micromonas, respectively, in the genome archive of the NCBI database. ANI comparisons revealed that the two MAGs in our study belonged to the species O. lucimarinus and M. commoda. Notably, one MAG, exhibiting 90.79% completeness and 1.27% contamination and derived from a shrimp farm sample, was identified as Ostreococcus. However, it represents a novel lineage, as evidenced by its comparison with the RNA polymerase phylogeny and NCBI genome databases, the highest ANI value was 77.4%, indicating no known representatives. This discovery of a MAG from an unidentified Ostreococcus lineage has important implications, as it holds the potential to significantly broaden our understanding of green algae diversity.

Phylogenetic tree of three non-redundant eukaryotic MAGs with METdb. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using IQ-TREE. The color of the circles indicates different genera. The two MAGs assigned to Ostreococcus are highlighted in yellow, whereas the single MAG assigned to Micromonas is highlighted in blue.

The distribution of the majority of MAGs was dependent on the type of mariculture organism (shrimp, n = 117; oyster, n = 59; scallop, n = 30; mussel, n = 12) (Fig. 2). In contrast, only 19 MAGs were recovered across two or more mariculture environments (Fig. 2). Most of these MAGs belong to the Proteobacteria (Alphaproteobacteria (n = 6) and Gammaproteobacteria (n = 5)) and Bacteroidetes (n = 4) phyla. In terms of the number of shared species MAGs, half of the MAGs recovered from mussel farm samples were shared with other farms, followed by oyster (23.38%), scallop (18.92%), and shrimp (7.14%). Notably, only one MAG, belonging to Planktomarina temperata, was present in all environments. This MAG was recovered in February, March, April, July, and November, suggesting that its presence is largely independent of seasonal variations. This MAG is a member of the Roseobacter clade-affiliated group and is well-known to be associated with phytoplankton blooms26,27,28 and has also been linked to total nitrogen and inorganic nitrogen levels, suggesting an association with mariculture-like anthropogenic influences.

To gain a more detailed understanding of microbial community structure, we employed a read-mapping strategy in addition to comparing recovered MAG compositions. An NMDS ordination analysis of microbial cosmopolitanism was conducted using the relative abundance of mapped reads. This analysis revealed a precise distribution of microbial communities across various mariculture organisms, which was consistent with the recovered MAG composition (Fig. 4A). Notably, nearshore mariculture samples from shrimp farms were distinct from offshore mariculture environments. Furthermore, oyster farm samples exhibited seasonal differences between spring, summer, and winter, and even more pronounced differences compared to other farming environments. This suggests that there are significant variations between the microbial communities of different farming environments, regardless of seasonal changes.

Read mapping-based analysis of MAGs and resistome distribution in mariculture environments. (A) NMDS plot illustrating the distribution of MAG abundance by type of mariculture organism. (B) Prevalence and abundance of MAGs harboring antimicrobial and metal resistance genes, as detailed in Table 1. (C) Heatmap depicting the resistome presence, determined by the coverage breadth exceeding 30% of each gene’s length, across sampling sites.

Of the 237 species-level prokaryotic MAGs, 22 contained 26 antibiotic and metal-resistance genes (resistomes), with 16 being beta-lactam-resistance genes found on most farms (Table 1). To obtain a detailed distribution of the 22 MAGs with resistomes, we calculated their prevalence in each mariculture environment using a relative abundance cutoff of >0.1%, as shown in Fig. 4B. Additionally, we assessed the exact presence of resistomes by calculating the read-mapped coverage breadth of each gene at each sampling site (Fig. 4C). Interestingly, while MAGs harboring beta-lactam resistance genes were widely distributed among farms (Fig. 4B), only a UBA9145 MAG (Pseudohongiellaceae family, MAG ID: Oyster_1.53.Bac) harboring subclass B3 metallo-beta-lactamase was consistently identified across various farms (Fig. 4C). In contrast, MAGs harboring multiple resistance genes—including those for beta-lactams, tetracyclines, macrolides, and fosfomycin, along with metal resistance genes for arsenic and mercury—were more diverse and abundant in shrimp farms compared to other environments (Fig. 4B,C). This diversity and abundance were observed regardless of the landfill farming environment or the surrounding ocean conditions at the shrimp farms. Additionally, a MAG (Shrimp_5.195.Bac) recovered from a shrimp farm belonging to the opportunistic pathogen Vibrio spp. was found to carry the tet(34) resistance gene. This MAG and its ARG were detected through a read-mapping strategy not only in shrimp farm samples but also in oyster farm samples, especially in summer, highlighting its potential as an important genetic resource for detecting fish and human health risks in the future.

Overall, this study provides valuable insights into the microbial communities across diverse mariculture settings in South Korea. This work also underscores the existence of diverse microbial taxa, including previously unidentified species, and explores the distribution of resistomes between different farms. While our metagenomic approach offers extensive coverage, it also reveals certain limitations in detecting risks from RNA viruses such as noroviruses and dinotoxins produced by dinoflagellates. Future research should thus focus on these areas to enhance our capabilities in monitoring and mitigating health risks in mariculture environments. Importantly, despite these limitations, the genomic resources elucidated in this study provide crucial insights into the impact of anthropogenic activities on marine ecosystems and offer valuable guidance for developing sustainable mariculture practices that protect ocean ecosystems and human health.

Methods

Sample collection and metagenome sequencing

Samples were obtained from surface waters in and around shrimp, oyster, mussel, and scallop farms from spring 2019 through winter 2021. The sampling dates and locations are provided in Supplementary Table S1. Water samples were collected using 25 L Round Nalgene LDPE bottles and promptly taken to the lab for processing. A peristaltic pump (Masterflex L/S peristaltic pump; Cole-Parmer, Vernon Hills, IL, USA) was used to pass water samples through a prefilter (mixed cellulose esters, 3.0-μm pore size; Merck-Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA) to remove floating particles. The samples were then filtered through a 0.22-μm pore size microbial collection filter (mixed cellulose esters; Merck-Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA). Following filtration, the filters were ground up, and DNA was extracted using the DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Metagenomic DNA libraries were constructed for each sample using the TruSeq DNA Nano Kit, and sequencing (paired-end 2 × 150 bp runs) was performed by Macrogen Inc. (Seoul, Korea) on the Illumina HiSeq X Ten platform.

Metagenomic assembly and genome binning

The raw sequence data were quality-filtered using the default options in FaQCs (v.2.09)29. To eliminate duplicate reads generated by Illumina patterned flow cells, identically paired reads were eliminated using FastUniq (v1.1)30. After quality filtering, high-quality reads for each sample were obtained and independent assembly was conducted using MEGAHIT (v.1.1.3)31, applying the ‘-presets meta-sensitive’ flag and filtering for contigs longer than 1 kbp.

Contig abundance was calculated by mapping high-quality reads from each sample to the assembled contigs using BWA-MEM (v.0.7.17)32. Unmapped reads were then removed and data was sorted with Samtools (v.1.3.1)33 using following commands: ‘samtools view -F 4 | samtools sort’. Contig coverage information were obtained using the jgi_summarize_bam_contig_depths module34. Subsequently, initial genome bins for each sample were reconstructed employing MetaBAT2 (v.2.12.1; default option)34. An additional refining step was performed via k-means clustering based on contig abundance (https://github.com/hoonjeseong/acr)35. The highest quality non-redundant species-level MAGs were selected with dRep (v.3.2.0)36 using average nucleotide identity (95%) clustering. The samples containing MAGs belonging to each represented species cluster were then identified to determine the farm from which they originated. Lastly, each MAG was taxonomically classified using the Genome Taxonomy Database Toolkit (GTDB-Tk, v.2.0.0)37.

Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic analyses for prokaryotic MAGs were conducted using PhyloPhlAn3 (v3.0.64)38, utilizing a set of 400 universal marker genes. Core genes were identified using DIAMOND (v.0.9.23)39 and aligned with MAFFT (v.7.407)40 and TrimAl (v.1.4)41. Phylogenies were then calculated with FastTree (v2.1.10)42 and RAxML-HPC (v.8.2.12)43. The outputs of the aforementioned steps were analyzed in PhyloPhlAn3 using the “–high diversity–fast–min_num_markers 100” flags. For the phylogenetic analysis of eukaryotic MAGs, RNA polymerase genes were searched using the HMM profile built by Delmont et al.44. Since all eukaryotic MAGs were classified within the Mamiellales clade according to the EukCC (v.0.2; database version: 2019-10-23.1)45 results, only the RNA polymerase genes from Delmont et al.44 that belonged to Mamiellales were used for an accurate phylogenetic analysis. These RNA polymerase genes were aligned using MAFFT40 with the FFT-NS-I algorithm, and phylogenies were constructed using IQ-TREE (v.1.6.12)46 with the following flags: “-m LG + F + R10 -alrt 1000 -bb 1000.” Subsequent visualization was performed using iTOL (v.6)47.

Gene prediction and antibiotic-resistance gene annotation

Gene prediction in each MAG was performed using Prodigal (v.2.6.3)48 and annotated with Prokka (v.1.12)49. AMRFinderPlus (v.3.10.36; database version: 2022-05-26.1)50 was then utilized with the nucleotide, protein sequence, and GFF files generated by Prokka48 to identify the precise ARGs.

Microbial composition analysis and mapped breadth coverage calculation of ARGs

To calculate the relative abundance of each MAG in the sample, all metagenomic reads were mapped back to representative mariculture MAGs using BWA-MEM (v.0.7.17)32. Briefly, all mapped reads for each MAG were quantified in normalized units of reads per kilobase per million mapped reads (RPKM) to adjust for genome size, followed by total sum scaling. The relative abundance table was generated using Bedtools (v.2.25.0)51 supplemented by an in-house script, followed by NMDS analysis conducted using the Vegan (v.2.6.4) package52 in the R environment53. Additionally, to determine the presence of ARGs in each sample, we calculated the mapped breadth coverage of each gene using Bedtools51, encoded in an in-house script. All aforementioned in-house scripts are described in the Code Availability section.

Data Records

The metagenomic raw data are available in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under BioProject identifier PRJNA111338654, with accession number SRP50883355. Information for the 240 representative MAGs has been deposited under the same BioProject identifier, with accession numbers SAMN4145434856 to SAMN4145458757. Additional detailed information is available in Supplementary Table S3. Fasta files of both representative and non-representative mariculture MAGs are accessible on Figshare, where detailed metadata is available25. Further data, including Prokka annotations and AMRFinder results for MAGs, along with the corresponding phylogenetic tree, can also be found on Figshare25.

Technical Validation

Genome completeness and contamination were assessed using CheckM (v.1.0.11)58 and EukCC45, utilizing a set of ubiquitous and single-copy genes within the phylogenetic lineage of prokaryotic and eukaryotic MAGs. For prokaryotic MAGs, marker genes were analyzed for phylogenetic relatedness using GUNC (v.1.0.1; database version: v.2.0.4)59 to ensure that the MAG catalog comprised only non-chimeric MAGs. The final catalog included genomes that satisfied the MIMAG60 criteria of at least 50% completeness and less than 10% contamination.

Code availability

All in-house Python codes used in the ‘Microbial composition analysis and mapped breadth coverage calculation of ARGs’ section are available through a GitHub repository at https://github.com/hoonjeseong/maricultureMAGs61.

References

Naylor, R. L. et al. Effect of aquaculture on world fish supplies. Nature. 405, 1017–1024, https://doi.org/10.1038/35016500 (2000).

Rosa, R., Marques, A. & Nunes, M. L. Impact of climate change in Mediterranean aquaculture. Rev. Aquacult. 4, 163–177, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-5131.2012.01071.x (2012).

Lulijwa, R., Rupia, E. J. & Alfaro, A. C. Antibiotic use in aquaculture, policies and regulation, health and environmental risks: A review of the top 15 major producers. Rev. Aquacult. 12, 640–663, https://doi.org/10.1111/raq.12344 (2020).

Rico, A. et al. Use of veterinary medicines, feed additives and probiotics in four major internationally traded aquaculture species farmed in Asia. Aquaculture. 412–413, 231–243, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2013.07.028] Subasinghe RP, Barg U, Tacon A. Chemicals in Asian aquaculture: need, usage, is sues and challenges. 1996. p. 1–6 (2013).

Subasinghe, et al. Chemicals in Asian aquaculture: Need, usage, issues and challenges. In: Use of Chemicals in Aquaculture in Asia: Proceedings of the Meeting on the Use of Chemicals in Aquaculture in Asia 20-22 May 1996 SEAFDEC Aquaculture Department, Tigbauan, Iloilo, Philippines, pp. 1–5 (2000).

Li, Z., Junaid, M., Chen, G. L. & Wang, J. Interactions and associated resistance development mechanisms between microplastics, antibiotics and heavy metals in the aquaculture environment. Rev. Aquacult. 14, 1028–1045, https://doi.org/10.1111/raq.12639 (2022).

Heuer, O. E. et al. Human health consequences of use of antimicrobial agents in aquaculture. Clin. Infect. Dis. 49, 1248–1253, https://doi.org/10.1086/605667 (2009).

Sapkota, A. et al. Aquaculture practices and potential human health risks: Current knowledge and future priorities. Environ. Int. 34, 1215–1226, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2008.04.009 (2008).

Limborg, M. T. et al. Applied hologenomics: Feasibility and potential in aquaculture. Trends Biotechnol. 36, 252–264, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibtech.2017.12.006 (2018).

Gutierrez-Perez, E. D. et al. How a holobiome perspective could promote intensification, biosecurity and eco-efficiency in the shrimp aquaculture industry. Front. Mar. Sci. 9, 975042, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2022.975042 (2022).

Desai, A. R. et al. Effects of plant-based diets on the distal gut microbiome of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Aquaculture. 350, 134–142, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2012.04.005 (2012).

Buttigieg, P. L. et al. Marine microbes in 4D-using time series observation to assess the dynamics of the ocean microbiome and its links to ocean health. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 43, 169–185, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mib.2018.01.015 (2018).

Vincent, F. et al. Viral infection switches the balance between bacterial and eukaryotic recyclers of organic matter during coccolithophore blooms. Nat. Commun. 14, 510, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-36049-3 (2023).

Lehel, J., Yaucat-Guendi, R., Darnay, L., Palotas, P. & Laczay, P. Possible food safety hazards of ready-to-eat raw fish containing product (sushi, sashimi). Crit. Rev. Food Sci. 61, 867–888, https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2020.1749024 (2021).

Wittman, R. J. & Flick, G. J. Microbial contamination of shellfish: prevalence, risk to human health, and control strategies. Annu. Rev. Public Health 16(1), 123–140 (1995).

Griffith, A. W. & Gobler, C. J. Harmful algal blooms: A climate change co-stressor in marine and freshwater ecosystems. Harmful Algae 91, 101590, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hal.2019.03.008 (2020).

Alfano-Sobsey, E. et al. Norovirus outbreak associated with undercooked oysters and secondary household transmission. Epidemiol. Infect. 140(2), 276–282, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268811000665 (2012).

Santos, L. & Ramos, F. Antimicrobial resistance in aquaculture: Current knowledge and alternatives to tackle the problem. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 52, 135–143, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2018.03.010 (2018).

Hammad, A. M., Shimamoto, T. & Shimamoto, T. Genetic characterization of antibiotic resistance and virulence factors in Enterococcus spp. from Japanese retail ready-to-eat raw fish. Food Microbiol. 38, 62–66, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fm.2013.08.010 (2014).

Xu, N. et al. A global atlas of marine antibiotic resistance genes and their expression. Water Res. 244, 120488, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2023.120488 (2023).

Tas, N. et al. Metagenomic tools in microbial ecology research. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 67, 184–191, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copbio.2021.01.019 (2021).

Delmont, T. O. et al. Nitrogen-fixing populations of Planctomycetes and Proteobacteria are abundant in surface ocean metagenomes. Nat. Microbiol. 3(7), 804–813, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-018-0176-9 (2018).

Nishimura, Y. & Yoshizawa, S. The OceanDNA MAG catalog contains over 50,000 prokaryotic genomes originated from various marine environments. Sci. Data. 9, 305, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01392-5 (2022).

Seong, H. J. et al. A case study on the distribution of the environmental resistome in Korean shrimp farms. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf 227, 112858, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.112858 (2021).

Seong, H. J. et al. Recovery of 240 metagenome-assembled genomes from coastal mariculture environments in South Korea. Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25866619 (2024).

Teeling, H. et al. Recurring patterns in bacterioplankton dynamics during coastal spring algae blooms. Elife. 5, e11888, https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.11888 (2016).

Wemheuer, B. et al. The green impact: Bacterioplankton response toward a phytoplankton spring bloom in the southern North Sea assessed by comparative metagenomic and metatranscriptomic approaches. Front. Microbiol. 6, 805, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2015.00805 (2015).

Buchan, A., González, J. M. & Moran, M. A. Overview of the marine Roseobacter lineage. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 5665–5677 (2005).

Lo, C. C. & Chain, P. S. Rapid evaluation and qualified ity control of next generation sequencing data with FaQCs. BMC Bioinform. 15, 366, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12859-014-0366-2 (2014).

Xu, H. et al. FastUniq: A fast de novo duplicates removal tool for paired short reads. PLoS One. 7, e52249, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0052249 (2012).

Li, D. et al. MEGAHIT v1.0: A fast and scalable metagenome assembler driven by advanced methodologies and community practices. Methods. 102, 3–11, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymeth.2016.02.020 (2016).

Li, H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. Preprint at arXiv https://arxiv.org/abs/1303.3997 (2013).

Li, H. et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 25, 2078–2079, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352 (2009).

Kang, D. D. et al. MetaBAT 2: An adaptive binning algorithm for robust and efficient genome reconstruction from metagenome assemblies. PeerJ. 7, e7359, https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.7359 (2019).

Seong, H. J., Kim, J. J. & Sul, W. J. ACR: metagenome-assembled prokaryotic and eukaryotic genome refinement tool. Brief. Bioinform. 24, bbad381 (2023).

Olm, M. R., Brown, C. T., Brooks, B. & Banfield, J. F. dRep: A tool for fast and accurate genomic comparisons that enables improved genome recovery from metagenomes through de-replication. ISME J. 11, 2864–2868 (2017).

Chaumeil, P.-A., Mussig, A. J., Hugenholtz, P. & Parks, D. H. GTDB-Tk: A toolkit to classify genomes with the Genome Taxonomy Database. Bioinformatics. 36, 1925–1927 (2020).

Asnicar, F. et al. Precise phylogenetic analysis of microbial isolates and genomes from metagenomes using PhyloPhlAn 3.0. Nat. Commun. 11, 2500 (2020).

Buchfink, B., Xie, C. & Huson, D. H. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods. 12, 59–60 (2015).

Katoh, K. & Toh, H. Recent developments in the MAFFT multiple sequence alignment program. Brief. Bioinform. 9, 286–298 (2008).

Capella-Gutiérrez, S., Silla-Martínez, J. M. & Gabaldón, T. trimAl: A tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics. 25, 1972–1973 (2009).

Price, M. N., Dehal, P. S. & Arkin, A. P. FastTree 2–approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PloS One. 5, e9490 (2010).

Stamatakis, A. RAxML version 8: A tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 30, 1312–1313 (2014).

Delmont, T. O. et al. Functional repertoire convergence of distantly related eukaryotic plankton lineages abundant in the sunlit ocean. Cell Genomics. 2, 100123 (2022).

Saary, P., Mitchell, A. L. & Finn, R. D. Estimating the quality of eukaryotic genomes recovered from metagenomic analysis with EukCC. Genome Biol. 21, 1–21 (2020).

Minh, B. Q. et al. IQ-TREE 2: New models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 37, 1530–1534 (2020).

Letunic, I. & Bork, P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v5: An online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, W293–W296 (2021).

Hyatt, D. et al. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC bioinform. 11, 1–11 (2010).

Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 30, 2068–2069 (2014).

Feldgarden, M. et al. AMRFinderPlus and the Reference Gene Catalog facilitate examination of the genomic links among antimicrobial resistance, stress response, and virulence. Sci. Rep. 11, 1–9 (2021).

Quinlan, A. R. BEDTools: the Swiss‐army tool for genome feature analysis. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics 47(1), 11–12 (2014).

Oksanen, J. et al. vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.6-4. 2022. Github https://github.com/vegandevs/vegan (2023).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing (2019).

Seong, H. J. et al. Recovery of 240 metagenome-assembled genomes from coastal mariculture environments in South Korea. BioProject https://identifiers.org/ncbi/bioproject:PRJNA1113386 (2024).

Seong, H. J. et al. Recovery of 240 metagenome-assembled genomes from coastal mariculture environments in South Korea. Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP508833 (2024).

Seong, H. J. et al. Recovery of 240 metagenome-assembled genomes from coastal mariculture environments in South Korea. BioSample https://identifiers.org/ncbi/biosample:SAMN41454348 (2024).

Seong, H. J. et al. Recovery of 240 metagenome-assembled genomes from coastal mariculture environments in South Korea. BioSample https://identifiers.org/ncbi/biosample:SAMN41454587 (2024).

Parks, D. H., Imelfort, M., Skennerton, C. T., Hugenholtz, P. & Tyson, G. W. CheckM: Assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res. 25, 1043–1055 (2015).

Orakov, A. et al. GUNC: Detection of chimerism and contamination in prokaryotic genomes. Genome Biol. 22, 1–19 (2021).

Bowers, R. M. et al. Minimum information about a single amplified genome (MISAG) and a metagenome-assembled genome (MIMAG) of bacteria and archaea. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 725–731 (2017).

Seong, H. J. et al. Recovery of 240 metagenome-assembled genomes from coastal mariculture environments in South Korea. Github https://github.com/hoonjeseong/maricultureMAGs (2024).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the “Korea National Institute of Health” (KNIH) research project (project No: 2023ER210300 and 2024ER211600).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.H.J. and K.J.J. wrote the manuscript, analyzed the data, and generated the figures. S.H.J. uploaded and archived the genomic data. A.S. and K.T. collected the samples and extracted the DNA for sequencing. R.M. reviewed the manuscript. S.W.J. and L.K.J. supervised the study. All authors approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Seong, H.J., Kim, J.J., Kim, T. et al. Recovery of 240 metagenome-assembled genomes from coastal mariculture environments in South Korea. Sci Data 11, 902 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03769-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03769-0