Abstract

Radioactive safety in nuclear facilities is of utmost importance. Prior to workers entering these areas, a 3D radiation field is needed for accurately estimating their exposure. Due to the complex relationship between radiation measurements and radiation fields, implementing neural networks is a promising approach for reconstruction. However, research on direct 3D radiation field reconstruction using neural networks is limited, and there is no standardized open-source dataset for training and evaluation. To address these issues, we created a simplified model of a nuclear facility and utilized the Monte Carlo program MCShield to simulate 3D radiation parameters. MCShield, which is mainly used for shielding calculations, has been verified for accuracy through benchmark tests. In addition, this paper proves the correctness of the MCShield program and the effectiveness of the AIS variance reduction method through calculations on the WinFrith Iron benchmark experiment and the NUREG/CR-6115 benchmark. The results show that the MCShield program as well as the AIS method can be used for dataset calculations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Modern society has a growing and urgent need for nuclear energy and technology. Various nuclear facilities, such as nuclear power plants, reactors, fuel production stations, storage areas, and waste disposal sites, serve this purpose. The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA)1 defines nuclear facilities as those handling radioactive materials on a significant scale. Nuclear facilities are characterized by radioactivity, and ensuring the safety of workers, the public, and the environment throughout the life cycle of nuclear facilities is vital. Ensuring nuclear and radiation safety is both a technical necessity and a social responsibility. To maintain public and environmental safety, radiation exposure to facility staff should be minimized (ALARA principle) during all stages, including construction, operation, maintenance, and decommissioning. This necessitates regular assessments of radiation levels within the facility for various activities, such as reactor refueling2, emergency response training2,3,4, evacuation planning5, and safety support6.

Before personnel enter a nuclear facility’s radiation area, it is critical to accurately calculate their potential radiation exposure by assessing the 3D radiation field. This precautionary measure is fundamental to minimize the exposure of operators to radiation. The establishment of a precise 3D radiation field is the focal point of such assessments, which can be approached through two main methods: direct calculation and direct reconstruction. To perform direct calculations, numerical methods such as the Monte Carlo method, which can be used to simulate the transport of radiation within the geometric space of the facility, should be employed. This method is particularly challenged by ‘deep penetration problems,’ a term that refers to the complexities involved in simulating radiation as it deeply penetrates dense materials within nuclear facilities. Such problems are characterized by significant attenuation of the radiation intensity, requiring advanced computational techniques to accurately trace the radiation paths and interactions. These interactions often involve a combination of scattering, absorption, and energy loss processes that can lead to large computational costs and require substantial computational resources to resolve7,8,9. Despite its precision, the Monte Carlo method can be impractical in certain scenarios, especially when the source term — the initial quantity and distribution of radiation — is not sufficiently defined. Without accurate source term information, the direct calculation may yield results with considerable uncertainty, thus compromising the safety evaluations for personnel exposure.

Direct reconstruction methods, including interpolation algorithms and artificial intelligence, analyze and reconstruct radiation fields from limited sampling points. While interpolation methods have been extensively studied10,11,12,13,14, they require many uniform sampling points that may not be available in real scenarios. In real radiation fields, detector parameters are influenced by source and scattering terms, often with nonlinear characteristics. This makes it challenging to establish a definitive mathematical model to relate scattered detector measurements to radiation parameters. Artificial intelligence methods, with neural networks as a prominent example, leverage techniques such as nonlinear activation functions, multilayer structures, high-dimensional representations, and data regularization to efficiently address complex nonlinear problems. This enables them to excel in domains such as image recognition and natural language processing while also holding the potential to be effective tools for radiation field reconstruction.

In the past decade, artificial intelligence (AI) has rapidly evolved, offering solutions to complex problems and showing potential in nuclear science and technology. AI can address pressing challenges in the nuclear field. In 2022, DeepMind and the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology achieved precise plasma control using AI15. AI continues to contribute to peaceful nuclear applications across seven areas, as outlined in the IAEA’s publication “Artificial Intelligence for Accelerated Development of Nuclear Applications, Science and Technology”16. These areas include human health, food and agriculture, water and the environment, nuclear science and fusion research, nuclear power, nuclear security, and assurance.

However, there are relatively few studies on direct reconstruction methods for 3D radiation fields based on artificial intelligence. There have been some preliminary related studies, as shown below. Li Mengkun et al.17 adopted a radial basis function (RBF) neural network model combined with a difference method to reconstruct a 2D radiation field, which was validated based on a simple dataset arithmetic example set by the authors themselves. Zhou Wen et al.18 adopted an adaptive back propagation (BP) neural network based on learning rate decay and validated it with several authors’ self-imposed dataset arithmetic cases. Hao Yisheng et al.19 verified the feasibility of 3D gamma radiation field reconstruction using a fully connected neural network.

In summary, artificial intelligence methods can play an important role in radiation protection calculations that cannot be ignored. A 3D radiation field reconstruction strategy based on artificial intelligence has yet to be developed. Unfortunately, there is no unified and complete dataset available for AI model training for 3D radiation field reconstruction. The existing studies are based on the training and validation of datasets generated by self-defined algorithms. Therefore, it is not possible to compare different neural network methods, which is not conducive to the development of this research. In addition, model training for an artificial intelligence strategy at a nuclear facility requires many radiation field parameters of all positions in space under the conditions of the same geometric scene and different source terms. Therefore, it is neither possible nor feasible to generate the dataset needed for training through actual measurements.

To solve the above problems, this paper constructs a simplification and model of typical nuclear facility space scenarios. Based on the distribution of different source terms, the Monte Carlo method is used to simulate the radiation parameter values at a nuclear facility space and finally generates an open-source dataset that can be used for artificial intelligence model training and verification. In the remaining part of this paper, the Monte Carlo simulation method, the Monte Carlo simulation program MCShield and its validation, the structure of the dataset algorithms, and the generation method are introduced in detail.

Methods

This chapter provides a detailed description of the Monte Carlo simulation methodology used in this paper, as well as the Monte Carlo simulation program MCSheild, and simplified arithmetic examples are provided for two typical nuclear facility scenarios in the dataset.

Introduction to the monte carlo method and program

Monte Carlo methods operate by calculating the statistical mean of an estimate as the solution to a problem. Monte Carlo methods were first applied in the testing and verification of nuclear weapons and played a crucial role in the U.S. Manhattan Project. In particle transport calculations, Monte Carlo methods can accurately describe 3D complex geometrical and physical reactions. Moreover, the convergence speed is independent of problem dimensionality, and computational errors can be easily discerned. In recent years, in the field of radiation protection, with the increasing demand for refined radiation shielding calculations, Monte Carlo methods and procedures have played an irreplaceable role in the simulation of full core refinement, shielding calculations, and shielding design optimization.

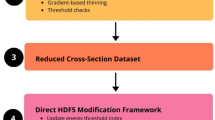

Tsinghua University Radiation Protection and Environmental Protection Laboratory developed MCShield20, which is a Monte Carlo software that is used for radiation shielding calculations. It simulates neutron, photon, and electron transport with parallel computations and effectively solves deep penetration and complex shielding problems in Monte Carlo variance reduction techniques. The software features robust pre- and postprocessing modules, including CAD geometry conversion, parametric modeling, parameter settings, particle trajectory display, and 3D dose visualization. It has been validated against international standards. Regarding deep penetration problems, the project team researched and developed specialized methods, such as FPAIS, SDAIS, CNPAIS, and grid-AIS platforms (as shown in Fig. 1). These methods greatly improve the computational efficiency.

Examples of spent fuel storage scenarios

As many nuclear power plants have begun to use the dry method for spent fuel storage, it is necessary to construct spent fuel storage system facilities for the away-from-reactor storage of spent fuel. Taking a dry process spent fuel transfer container as an example, this paper constructs a simplified arithmetic example under the spent fuel storage scenario to further create the above simulation dataset.

In this example, the calculation area is a cubic room with a side length of 10000 mm. Moreover, the thickness of the surrounding walls is 200 mm, and the material is concrete. The whole room is divided into two sides by a 200 mm wall. A spent fuel transfer container is placed vertically inside the room. The outer diameter of the container is 2340 mm, the inner diameter is 2200 mm, the height is 5000 mm, the bottom thickness is 200 mm, the container lid is 2400 mm, the height is 200 mm, and the container is made of stainless steel. At the same time, a cylindrical room beam with a diameter of 1000 mm and a height of 5800 mm is placed above the inner room to increase the geometric complexity. In this calculation example, the positions and coordinates of the main geometry are given in Table 1, and the geometric diagram is shown in Fig. 2.

Examples of small modular reactors

Characterized by high safety, small size and multipurpose features, nuclear power plants have become faster and cheaper to build and safer to operate, and small modular reactors are becoming a future development trend for nuclear power. Based on a common small reactor design, this paper constructs a simulation dataset by using complex geometric examples of small reactors.

In this example, the calculation area is a rectangular room, with a length, width and height of 15400 mm, 12400 mm and 12400 mm, respectively. The coordinates of the lower left corner are (−4200, −4200, −1200). Moreover, the thickness of the surrounding walls is 200 mm, and the material is concrete. Shielding wall 1 is at (100, 10000, 12200). Shielding wall 2 is at (2100, 100, 12200). For Beam 1, the diameter is 200 mm, and the height is 8000 mm. For Beam 2, the diameter is 200 mm, and the height is 8000 mm.

The reactor was placed in a rectangular room. The reactor has an outer diameter of 2000 mm, a thickness of 100 mm, a height of 3000 mm, a hemispherical lower part, and four 300 mm diameter pillars made of stainless steel. A pressure vessel cover with a diameter of 3500 mm and a height of 500 mm is placed on the upper part of the reactor pressure vessel, which is made of stainless steel, and two main pumps with a height of 1600 mm and ten steam generators with a height of 850 mm are placed on the upper part, which are finally connected to two pressurizers with a diameter of 1500 mm and a length of 3500 mm to increase the complexity of the geometry. In this calculation example, the position and coordinates of the main geometry are given in Table 2, and the geometric diagram is shown in Fig. 3.

Monte carlo simulation parameter setting

In the calculation example presented in the article, the source term is defined as a custom neutron source with a Watt fission spectrum. During the simulation process, since nuclear facility containers are typically cylindrical in shape, the outer surface of the container can be treated as a curved source term. The surface intensity of the container exterior is utilized as the source strength, which allows the two-dimensional source term to be abstracted into a two-dimensional array. This array is characterized by two dimensions: the discretized circumferential angles and the axial discretized grids of the source term. As a result, the curved source term within the example is discretized into a series of subcurved sources for the purpose of the simulation. During the Monte Carlo simulation, the source term particles are uniformly ejected outward in the region with a certain intensity, assuming that the energy spectrum does not change. In the example described in this paper, the entire cylindrical container has a total of 360 degrees, which is divided into 30 angles for sampling. Each angle is divided into 20 regions for sampling, as shown in Fig. 4. For each example, 10,000 sets of examples are calculated as datasets. The number of simulated particles is 10000000, and the average statistical error is approximately 0.07. The MESH method is used to count the neutron flux in the whole calculation area, the side length of the MESH grid is 160 mm, and 64 MESH grids are set along the X, Y, and Z directions.

In this article, the 2D array above represents the strength of the discrete mesh for each source term. In the example, the intensity distribution of the source term is in the form of a 2D trigonometric function. When a set of source term distributions is generated, the parameters in the function are randomly sampled, including the series, amplitude, frequency and phase of the trigonometric function, and then the circumferential and axial coordinates of the source term are substituted into the 2D distribution function obtained by sampling to generate a set of source term parameters. To make the intensity distribution of the generated source term change continuously in both the circumferential and axial directions, a binary function is used to represent the source term intensity of each mesh, and a plurality of trigonometric functions with random parameters are used to represent the change trend of the source term intensity. The formulas are shown below:

In this context, F(x, y) represents the source intensity at the circumferential grid x and the axial grid y. The parameters order, amp, freq, and φ are sampled randomly within a specified range according to a certain rule for each dataset generation. The sampling rules and ranges for these parameters can be customized each time the dataset is generated. For instance, the sampling conditions for the parameters in the dataset shown below are set as follows: order ∈ [1, 5], amp ∈ [1, 5], freq ∈ [0.001,0.5], and φ ∈ [−5,5]. Figure 5 below illustrates examples of two-dimensional distributions for different source terms in the dataset.

Data Records

Dataset storage structure

The dataset is available on Figshare21. Figure 6 shows the storage structure of the dataset described in this paper. The dataset contains two abstract simple geometric scenarios: spent fuel storage and small modular reactors. The geometry, material, source term and statistical information of each geometric scene have been introduced above.

For each simple geometric scene, 10,000 different calculation examples are calculated as a dataset, and the data contained are divided into three parts: neutron radiation field flux, neutron radiation field statistical error and source term distribution. Among them, the neutron radiation field flux refers to the neutron flux counted by each MESH grid in the entire space; the neutron radiation field statistical error refers to the statistical error of the neutron flux counted by each MESH grid in the entire space; and the source term distribution refers to the 2D source term distribution of the example.

In this dataset, the data are stored in feather format. Feather is a lightweight, fast and interoperable data format widely used for data science and data analysis tasks. Its design goal is to enable efficient data exchange between different programming languages and data processing tools. The advantages of the feather format are as follows: the read and write speed of the feather file format is very fast; it is especially suitable for processing large datasets; the feather format usually generates smaller files and requires less disk space than other file formats (such as CSV or JSON); and the files can be easily read and written in many programming languages, such as Python, R, and Julia. Feather files can retain the data type information. When the data are read, the type of data can be accurately restored, avoiding the loss caused by data type conversion.

Technical Validation

The MCShield Monte Carlo particle transport calculation program20 used to generate the dataset described in this paper has been validated against dozens of international benchmarks and further verified the correctness and efficiency of the MCShield program for solving complex deep penetration problems. This paper takes the WinFrith Iron benchmark experiment22 and the NUREG/CR-6115 PWR pressure vessel fluence rate calculation benchmark23 as examples to verify the correctness of the MCShield Monte Carlo particle transport calculation program and the efficiency of the variance reduction method.

Program correctness verification

The WinFrith Iron benchmark experiments were conducted on the Winfrith UK Atomic Energy Establishment’s ASPIS Universal Shield. The experiment needs to measure the neutron energy spectrum and reaction rate of a 1 m thick large iron shield at different depths. The experimental setup is installed on a light water cooled, graphite and light water moderated NESTOR reactor with a reactor power of 30 kW. The natural uranium conversion target is driven by the NESTOR neutron source to provide a fission neutron source with a cross-section similar to a disk. The spatial distribution of the fission rate on the side of the conversion target near the core is measured by a calibrated 0.05 mm thick natural uranium foil. The measurement results are averaged around the azimuth angle. This experiment requires measuring the neutron energy spectrum and reaction rate of a 1 m thick large iron shield at different depths. Since the shielding layer in this benchmark question model is very thick, the penetration distance of the particles is relatively long. Therefore, as the penetration Counting particles and flux density numbers decay exponentially with increasing distance.

To verify the correctness of the MCShield program, this example calculates the neutron fluence rate spectrum of four detectors (22.86 cm, 57.15 cm, 85.73 cm, and 114.3 cm from the iron shield boundary) and uses the reference experimental measurement values. Source particles are generated by the NESTOR reactor and the source conversion target. The neutron source intensity on the source conversion target is directly given in the benchmark question report. The number of particles calculated by the MCShield program is 1 × 108. The neutron fluence rate spectrum results of the four detectors are shown in Figs. 7–10. Regarding the neutron fluence rate energy spectrum calculation results, the deviations between MCShield and the Monte Carlo reference results are within the statistical error range and are in good agreement with the experimental measurement values, meeting the program correctness verification standards.

Variance reduction methods efficiency verification

The NUREG/CR-6115 PWR pressure vessel injection rate calculation benchmark was developed by the BNL (Brookhaven National Laboratory) laboratory. The benchmark provides a very detailed source term and model data, and reference solutions (neutron only) for a variety of PWR shielding calculation problems are computed using the deterministic SN program DORT. This paper selects the standard fabric scheme in the benchmark as the calculation object. The total thermal power of the reactor in the NUREG/CR-6115 PWR benchmark is 2527.73 MW, and the core contains 204 fuel assemblies with different burnup depths, which give a 15 × 15 power distribution inside the fuel assemblies. The entire pressurized water reactor structure mainly consists of the core, basket, thermal shield, pressure vessel and concrete biological shield. The pressurized water reactor is described by a 1/8 model, with the 0° and 45° side boundaries of the model set as reflection boundaries and the exterior of the concrete biological shield, as well as the top and bottom of the model set as vacuum boundaries. Specific data of the source terms, geometry, materials, etc., have been introduced in detail in the benchmark report. The thickness of the concrete biological shield given in the benchmark is 216.36 cm, but the thickness used in the benchmark calculation is only 45.085 cm, and there is no calculation of any data for the interior and exterior of the concrete biological shield. In this paper, the thickness of the concrete biological shield is set to 216.36 cm.

In this paper, two examples of NUREG/CR-6115 benchmarks are calculated. The radial and axial flux distributions of the neutron/photon concrete biological shield are used to verify the solution of the complex deep penetration problem of coupling transport with very low penetration. All examples were calculated using the MCShield program, and the calculation results were compared with the Monte Carlo calculation results provided in the benchmark report. Among them, the Monte Carlo calculation results in the benchmark report were obtained using geometric splitting and the roulette variance reduction technique (IMP-MC), and the MCShield program used the CNP-AIS variance reduction technique for calculation. The regional importance distribution of the geometric splitting and roulette trick for neutron transport is consistent with the benchmark, while the regional importance distribution of photon transport is consistent with neutron transport.

Radial flux distribution of neutrons/photons in a concrete biological shield

Six cylindrical planes with radii of 370, 400, 430, 460, 490, and 520 cm are added radially inside the concrete biological shield, and the total neutron/photon fluxes of these six planes as well as the outer plane of the concrete biological shield (549.275 cm) are counted. Among them, the number of simulated particles of the IMP-MC method is 4 × 107, and the calculation time is 2990.00 min. The CNP-AIS method introduces 11 cylindrical neutron and photon virtual planes with radii of 188, 215, 230, 340, 360, 390, 420, 450, 480, 510, and 530 cm, with an NPS of 1 × 105 and a computation time of 28.33 min.

The statistics for neutrons are shown in Table 3, and the resulting fitted curves and the FOM curves are shown in Fig. 11. The statistical results for photons are shown in Table 4, and the resultant fit curves and the FOM curves are shown in Fig. 12. For cylindrical planes 1, 2, 3, and 4, the statistics of the IMP-MC method and the CNP-AIS method are in good agreement, and the relative Monte Carlo errors of both the IMP-MC method and the CNP-AIS method are below 10%. Regarding Cylindrical Planes 5, 6, and 7, the IMP-MC method does not provide plausible results, and the Monte Carlo relative errors of the CNP-AIS method are still all below 10%. The FOM of the IMP-MC method shows an exponential decreasing trend with increasing penetration thickness, while the FOM curve of CNP-AIS remains basically stable. The FOM of the first statistical plane of the IMP-MC method and the CNP-AIS method remains at the same order of magnitude, and the FOM of the penultimate plane of the CNP-AIS method is four orders of magnitude higher than that of the IMP-MC method. For the photon calculation results, a similar performance is seen in Table 4 and Fig. 12. In this example, the CNP-AIS method consumes only a short computation time (28.33 min) but shows very good computational performance.

Axial flux distribution of neutrons/photons in concrete biological shields

We set up a cylindrical plane with a radius of 490 cm as a neutron statistic plane and a cylindrical plane with a radius of 520 cm as a photon statistic plane. From Z = 0 cm to Z = 382.115 cm, these two statistical planes are divided into 13 segments in the axial direction, and the segmentation point positions Z = 30, 60, 90, 120, 150, 180, 210, 240, 270, 300, 330, and 360 cm are used to count the fluxes on these 13 segments. Among them, the simulated particle number of the IMP-MC method is 4 × 107, and the calculation time is 2890.00 min. The virtual plane introduced by the CNP-AIS method is the same as before, the number of simulated particles is 1 × 106, and the calculation time is 271.67 min.

The statistics of the neutrons are shown in Table 5. The resulting fitted curves and the FOM curves are shown in Fig. 13. The statistical results of the photons are shown in Table 6. The resultant fitting curves and the FOM curves are shown in Fig. 14. Analyzing the data in the graphs shows that the average Monte Carlo relative error of the IMP-MC method is 65.59% for neutrons and 61.16% for photons, which still does not give credible results within the unacceptable computation time. The average Monte Carlo relative error of the CNP-AIS method is 4.50% for neutrons and 2.78% for photons, giving very accurate results in a shorter time. The neutron and photon FOM curves of the CNP-AIS method are both approximately 3~4 orders of magnitude higher than those of the IMP-MC method, and the computational performance of the CNP-AIS method is much better than that of the IMP-MC in this example.

Code availability

The dataset described in this paper was generated using the MCShield program20 and the dataset is available on Figshare21. The MCShield program is a neutron/photon/electron coupled transport Monte Carlo program independently developed by the Radiation Protection and Environmental Protection Laboratory of Tsinghua University for radiation shielding calculations. Usually, Monte Carlo programs used for particle transport calculations do not have open-source program codes (for example, MCNP programs), which is also an important reason for the lack of related unified datasets. In addition, all input files and other information used to generate the database mentioned in this article, as well as related code, have been uploaded to Figshare21. The data processing steps of this article were performed using scripts written in the Python programming language.

References

IAEA. IAEA safety glossary: terminology used in nuclear safety and radiation protection. 15-25 (IAEA, Vienna, 2016).

Ródenas, J., Zarza, I., Burgos, M. C., Felipe, A. & Sánchez-Mayoral, M. L. Developing a virtual reality application for training nuclear power plant operators: setting up a database containing dose rates in the refueling plant. Radiat. Prot. Dosimetry 111, 173–180 (2004).

Sanders, R. L. & Lake, J. E. Training first responder to nuclear facilities using 3D visualization technology. In Proceedings of the 2005 Winter Simulation Conference, Orlando, FL, USA, 914–918 (2005).

Xi, C. et al. 3D Virtual reality for education, training and improved human performance in nuclear applications. In ANS NPIC HMIT 2009 Topical Meeting, Knoxville, Tennessee, USA, Paper 61801 (2009).

Mól, A. C. A., Jorge, C. A. F. & Couto, P. M. Using a game engine for VR simulations to support evacuation planning. IEEE Comput. Graph. Appl. 28, 6–12 (2008).

Silva, M. H. et al. Using virtual reality to support the physical security of nuclear facilities. Prog. Nucl. Energy 78, 19–24 (2015).

Pan, Q. et al. Pointing Probability Driven Semi-Analytic Monte Carlo Method (PDMC) – Part I: Global Variance Reduction for Large-scale Radiation Transport Analysis. Comput. Phys. Commun. 291, 108850 (2023).

Pan, Q. et al. Density-extrapolation Global Variance Reduction (DeGVR) Method for Large-scale Radiation Field Calculation. Comput. Math. Appl. 143, 10–22 (2023).

Pan, Q. & Wang, K. An adaptive variance reduction algorithm based on RMC code for solving deep penetration problems. Ann. Nucl. Energy 128, 171–180 (2019).

Wang, Z. & Cai, J. Inversion of radiation field on nuclear facilities: A method based on net function interpolation. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 153, 27–34 (2018).

Wang, Z. & Cai, J. Reconstruction of the neutron radiation field on nuclear facilities near the shield using Bayesian inference. Prog. Nucl. Energy 118 (2020).

Khuwaileh, B. A. & Metwally, W. A. Gaussian process approach for dose mapping in radiation fields. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 52, 1807–1816 (2020).

Zhu, S. et al. 3D gamma dose rate reconstruction for a radioactive waste processing facility using sparse and arbitrarily-positioned measurements. Prog. Nucl. Energy 144 (2022).

Zhu, S. et al. 3D gamma radiation field reconstruction method using limited measurements for multiple radioactive sources. Ann. Nucl. Energy 175, 109247 (2022).

Degrave, J. et al. Magnetic control of tokamak plasmas through deep reinforcement learning. Nature 602, 414–419 (2022).

Brown, D. Artificial Intelligence for Accelerating Nuclear Applications, Science, and Technology. Report No. Brookhaven National Lab. (BNL), Upton, NY (United States), (2022).

Li, M.-K. et al. A fast simulation method for radiation maps using interpolation in a virtual environment. J. Radiol. Prot. 38, 892–907 (2018).

Zhou, W. et al. BP neural network based reconstruction method for radiation field applications. Nucl. Eng. Des. 380 (2021).

Hao, Y. et al. Validation of the Neural Network for 3D Photon Radiation Field Reconstruction Under Various Source Distributions. Front. Energy Res. 11, 248 (2023).

Gao, S. et al. Development of a radiation shielding Monte Carlo code: RShieldMC. (2017).

Hao, YS. et al. A Monte Carlo Simulation Dataset of Radiation Field Parameters for a Simple Nuclear Facility Scenario, Figshare, https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.c.6819930.v1 (2024).

Butler, J. et al. Results and Calculational Model of the Winfrith Iron Benchmark Experiment. NEACRP-A-629, (1984).

Carew, J. F. PWR and BWR pressure vessel fluence calculation benchmark problems and solutions. Division of Engineering Technology, Office of Nuclear Regulatory Research, US Nuclear Regulatory Commission (2001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yisheng Hao: methodology, implementation, data curation, writing- original draft preparation. Zhen Wu: data processing, technical validation, writing – review & editing. Yanheng Pu: conceptualization, resources, supervision, writing – review & editing. Yang Zhou: software, supervision, writing – review & editing. Rui Qiu: supervision, writing – review & editing. Hui Zhang: supervision. Junli Li: methodology, resources, writing – review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Author WU Zhen was employed by Nuctech Company Limited. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hao, Y., Wu, Z., Pu, Y. et al. A Monte Carlo Simulation Dataset of Radiation Field Parameters for a Simple Nuclear Facility Scenario. Sci Data 11, 1008 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03799-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03799-8