Abstract

Site-specific crop management in heterogeneous fields has emerged as a promising avenue towards increasing agricultural productivity whilst safeguarding the environment. However, successful implementation is hampered by insufficient availability of accurate spatial information on crop growth, vigor, and health status at large scales. Challenges persist particularly in interpreting remote sensing signals within commercial crop production due to the variability in canopy appearance resulting from diverse factors. Recently, high-resolution imagery captured from unmanned aerial vehicles has shown significant potential for calibrating and validating methods for remote sensing signal interpretation. We present a comprehensive multi-scale image dataset encompassing 35,000 high-resolution aerial RGB images, ground-based imagery, and Sentinel-2 satellite data from nine on-farm wheat fields in Switzerland. We provide geo-referenced orthomosaics, digital elevation models, and shapefiles, enabling detailed analysis of field characteristics across the growing season. In combination with rich meta data such as detailed records of crop husbandry, crop phenology, and yield maps, this data set enables key challenges in remote sensing-based trait estimation and precision agriculture to be addressed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Site specific crop management in heterogeneous fields is widely recognized as a promising avenue towards increasing the efficiency and sustainability of agricultural production1,2,3. Timely availability of accurate, spatially explicit information on crop growth and vigor, phenological development, and health status is key for the implementation of such practises4. Over the past 10 to 15 years, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) equipped with various lightweight sensors have become instrumental in collecting such data, with ongoing efforts to enhance data interpretation and link remotely sensed proxies to vegetation characteristics5,6,7,8,9,10,11. A key advantage of UAV-based vegetation monitoring is its temporal and spatial flexibility, along with the high spatial resolution (i.e., ground sampling distance [GSD]) of data products4. However, the monitoring area is limited compared to high-altitude platforms such as satellites. Therefore, the transferability of methods to infer plant or vegetation characteristics from remotely sensed signals across scales is of significant interest (see e.g.,12,13,14). High-resolution imagery offers significant potential for calibrating and validating crop trait estimation methods based on remote sensing data15,16,17,18.

A major challenge in interpreting remote sensing signals in the context of commercial crop production is the large variability in the appearance of crop canopies within and across sites and over - sometimes very short - periods of time. While some of the within-field variability is relevant for designing tailored management interventions1, it can also result from soil-related factors, cultivar properties, or management practices per se. For example, a single pass with a harrow can significantly alter the appearance of crop canopies instantly, without affecting physiological status or biophysical characteristics. Therefore, robust methods applicable across a broad range of scenarios typically encountered in practise are essential to accelerate the adoption of precision agriculture principles in commercial production.

In the context of this challenge, here we describe a large multi-scale data set comprising (i) nearly 35,000 high-resolution (~2.7 mm to ~8 mm GSD), geo-referenced, aerial RGB images captured from altitudes of 10 m, 30 m, and 50 m; Along with the raw imagery, we provide geo-referenced orthomosaics and digital elevation models as well as shapefiles describing the position of all relevant subareas (field borders, reference areas, treatments); (ii) co-registered ground-based images with a very high spatial resolution (~0.4 mm GSD); (iii) Sentinel-2 satellite imagery with a GSD of 10 m, for nine commercial wheat fields with contrasting management located across the central plains of Switzerland from before tillering to after harvest; finally (iv) we provide rich meta data characterizing each flight and each field.

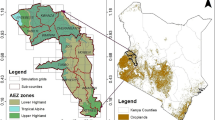

The original main purpose of this data set was to assess the feasibility of UAV-based weed monitoring at critical growth stages under a range of environmental and management conditions7. Chemical, mechanical, and no weed control measures were applied to subareas of each field. Imaging procedures covered all treatments. An overview of the experimental sites and the measurement campaign is given in Table 1 and Fig. 1. Basic phenology and yield maps are available for some and detailed documentation of crop management is available for all fields. Binary vegetation-soil segmentation masks are provided for ground-based and UAV-based aerial images as a benchmark for the estimation of vegetation cover, along with estimates of their accuracy.

Overview of the measurement campaign that produced the published data set. Nine commercial wheat fields (indicated by the name of the municipality in the grey boxes) were imaged throughout the main growing season of 2020 using hand-held cameras at a distance to the soil of approximately 1.5 m, and unmanned aerial vehicles at different flight altitudes (10 m, 30 m, and 50 m). Measurements during the early growing season can be roughly grouped into measurement events that span 1–3 days (indicated by green vertical bars). Most measurements were performed during early growth stages (GS 20–33), with a last measurement performed shortly before or during heading (GS 44–54; indicated by green vertical bars). An additional 1–2 flights were carried out during maturation (GS 85–87; yellow vertical bars), and a final flight was performed after harvest (red vertical bars) on most sites. Numbers represent the estimated growth stage at the time point of imaging.

This systematically structured data set (multiple sites, frequent measurements, measurements across scales) and rich meta data allow to address several current challenges related to remote-sensing-based trait estimation and precision agriculture. For example, relationships between remotely-sensed vegetation properties throughout the growing season estimated at different scales, and yield patterns could be explored, which may help improving remote-sensing-based yield predictions (e.g.,19,20,21). Methods for the estimation, interpretation, and improved temporal interpolation of various traits estimated from satellite data could be calibrated and validated using accurate estimates from high-resolution imagery (e.g.,22). This is a promising approach especially as such trait retrieval accuracy strongly depends on the phenological stage of the targeted canopy23. Similarly, the comparably low accuracy of our benchmark method for vegetation cover estimation in images captured at 50 m altitude highlights the need for approaches that perform better at lower spatial resolution (see e.g.,24,25,26). Furthermore, temporal and spatial stability as well as potential drivers of field heterogeneity could be examined across scales27. This may include analyses of the effect of management operations and meteorological conditions on field heterogeneity, as well as spatial correlations with yield. The data set offers the opportunity to calibrate and validate methods across a representative sample of contrasting application scenarios7.

Methods

The nine wheat fields, belonging to eight different farms, are distributed across the central plains of Switzerland. Large differences in soil type and composition as well as weather conditions during the growing season were observed between the experimental sites (Table 1). All experimental fields were imaged using DJI Phantom 4 pro (SZ DJI Technology Co. ltd., Shenzhen, China) with their integrated CMOS RGB sensor (5472 × 3648 pixels), and the areas of the plots used for reference data collection (1 m2 reference plots) were additionally photographed at ground level at a distance of about 1.5 m from the ground using a Canon EOS 600D and a Canon EOS 700D (5184 × 3456 pixels). Experimental fields were revisited 6–8 times during the early vegetation period (growth stages [GS] 20–3328). Flights were performed, whenever possible, under stable light conditions around noon, though some deviations were unavoidable given the extent of the measurement campaign. At 10 m altitude, the UAV was set to fly at 1 m/s with a front overlap ratio of 90 % and a side overlap ratio of 80 % (~2.7 mm/pixel GSD), covering over 100 m2 per flight. Flights at 30 m altitude covered more than 1 ha using the same overlap ratio but at a higher flight speed (2.2 m/s), resulting in a GSD of ~8 mm/pixel. The camera was set to a fixed aperture (F/2.8) for all flights, the ISO was varied according to the conditions but kept to a maximum of 400 and the shutter speed was set to a maximum of 1/1250s.

For further processing and comparison over time, each field was equipped with approximately 30 ground control points (GCP), with a higher density in the area of the 10 m flights and a lower density in the higher altitude flights (30 m and 50 m). The GPS position of the GCPs was measured using a GNSS Differential Global Positioning System (R10, Trimble ltd., Sunnyvale, U.S.A.) with a swipos-GIS/GEO real time kinematic (RTK) correction signal (Federal Office of Topography Swisstopo, Wabern, Switzerland). The acquired images were further processed into digital elevation models (DEM) and geo-referenced orthomosaics using the structure-from-motion-based software Agisoft Metashape Professional 1.5.2 (Agisoft LLC, St. Petersburg, Russia). A detailed list of the processing steps was published previously7.

Aerial images were segmented pixel-wise into a vegetation and a background soil fraction based on color properties of pixels, using a random forest classifier7. The classifier was trained by sampling training pixels from one randomly selected image per flight, resulting in 3626 instances belonging to 65 images. The sampled training data is included in the data set.

Sentinel-2 satellite images corrected for atmospheric effects (processing level 2A) were obtained from Microsoft Planetary Computer using the open-source Earth Observation data analysis library (EOdal)29 for all nine field plots. Only the spectral bands with a GSD of 10 m were downloaded, namely the blue (B02), green (B03), red (B04) and near-infrared (B08) bands. Only Sentinel-2 scenes with a scene-wide cloud cover of less than 10% were acquired to ensure minimal cloud and cloud shadow contamination. In addition, the scene-classification layer (SCL) provided as part of each scene was used to filter out all pixels not classified as “vegetated” (SCL class 4) or “bare ground” (SCL class 5). UAV and Sentinel-2 imagery are provided in Swiss national coordinate reference system (CH1903+ / LV95) and UTM32N, respectively.

Data Records

The dataset is publicly available from the ETH Zurich publications and research data repository30. It is structured first according to data type (‘raw’ - single RGB images, ‘processed’ - orthomosaics and digital elevation models resulting from photogrammetric processing, ‘sat_data’ - Sentinel-2 satellite imagery, and ‘Meta’ - meta information). Within each folder there is one sub-directory per field (see Table 1). These are further structured according to the type of image acquisition (‘10m’, ‘30m’, ‘50m’ or ‘handheld’) and then according to the date of acquisition (YYYYMMDD). The raw data folders also contain the vegetation masks (‘vegmask’; Fig. 2) and the detected sowing rows (for handheld and 10 m flights) for each date.

Variability in the appearance of wheat canopies across sites as documented in ground-based high-resolution images at early growth stages. Images are from different measurement dates that correspond to growth stages 20–33 (cf. Fig. 1). The left tile of each image shows the original image, the middle tile is the vegetation - soil mask overlaid on the original image, the right tile shows the final pixel classification into soil background, and green, chlorotic, and necrotic vegetation. (a) Nennigkofen1, (b) Treytorrens-Payerne, (c) Oleyres, (d) Volken, (e) Opfertshofen, (f) Villars-le-Grand, (g) Steinmaur, (h) Nennigkofen2, (i) Grafenried.

On the same level, the folder ‘validation’ contains all data that was used for the technical validation of the data set, and all outputs generated during validation. The sub-directories ‘frame_coord_*’ contain the image coordinates of the reference areas; sub-directories ‘handheld’, ‘10m’ and ‘50m’ contain the sampled images and masks for the technical validation and all generated outputs; ‘models’ contains the trained segmentation models.

Several types of meta information can be found in the Meta folder. For each UAV flight, the estimated real-world coordinates of the image corners (‘corners’) are provided, as well as masks for the validation (‘frames’) and the applied weed management treatments (‘treatments’) as .geojson files. Furthermore, for each field, management data can be found. These include sowing dates, variety information, and fertilization or crop protection measures. In addition, yield maps are provided for several fields. Note that these are raw data and may have to be pre-processed according to the needs associated with specific research questions. For each field a .geojson file is provided indicating the covered area for the 10 m and 50 m flight altitude (‘field_mask’). Details on camera parameters can also be found in the meta folder (‘UAV_meta’). A .csv file provides the UAV number used for each flight (three equal models were used) along with an estimate of cloud cover, wind speed, and crop development ratings at the time of the flight. The UAV number refers to available .xml file storing the estimated camera parameters. Finally, ‘UAV_meta’ contains all GCP coordinates. Though all steps involved in photogrammetric processing of the raw imagery have been thoroughly optimised, the available information on the camera parameters and the GCP positions on each field enable this process to be repeated and modified as needed by any qualified person.

Technical Validation

Visual inspection of the products of photogrammetric processing (orthomosaics) indicated a high spatial accuracy with minor deviations in the GCP and reference area positions across flights and across flight heights for all experimental fields, with absolute x and y errors well below 10 cm. In a few cases, localized inhomogeneities in the orthomosaics related either to changes in light conditions during the flight (see e.g., Fig. 3e) or to abrupt changes of the viewing angles of contributing single images can be observed. Neither of these issues would appear to be problematic as long as single geo-referenced images are used for analyses, which is facilitated here by the availability of real-world corner coordinates for each individual image based on back propagation31.

Orthomosaics for all nine experimental sites at early growth stages, based on images captured from an altitude of 10 m. The regularly spaced white dots are the ground control points (GCPs). Note that UAV flights performed at altitudes of 30 m and 50 m cover significantly larger areas, but cover the zones included in the 10 m flights as well. (a) Nennigkofen1, (b) Treytorrens-Payerne, (c) Oleyres, (d) Volken, (e) Opfertshofen, (f) Villars-le-Grand, (g) Steinmaur, (h) Nennigkofen2, (i) Grafenried. This Figure was originally published in7.

To quantify the suitability of the aerial images for estimation of key parameters such as vegetation cover, ground-based high-resolution images were segmented using a deep convolutional neural network (restnet34 - unet++32,33) that was trained using the VegAnn dataset18 following a previously described procedure34. The resulting vegetation fraction in the ground-based high-resolution images was further segmented into a green, chlorotic, and necrotic fraction using a previously trained random forest classifier34. This provided an accurate reference value of vegetation cover for the designated reference areas in each field at each time point. Given the high quality of the segmentation (see examples in Fig. 2), they could be used to quantify the accuracy of the UAV-based vegetation cover estimates. For this, we co-registered the high-resolution images and the corresponding segmentation masks to the UAV-based aerial images and their segmentation masks. This was accomplished by first identifying the aerial image providing the most nadir-view for each reference area using their estimated real-world corner coordinates, and then estimating the homography matrix between the high-resolution image and the aerial image based on the four corners of each reference area (Figs. 4, 6). The 3 × 3 homography matrix mapping corresponding points from the source plane to the destination plane was computed by setting up and solving a system of linear equations derived from the four pairs of matching points. Pixel-level metrics for the agreement between the segmentation masks were moderate on average, with F1 values ranging from 0.23 to 0.93 with a mean of 0.55, and from 0.03 to 0.93 with a mean of 0.48, for images taken from 10 m and 50 m flight altitude, respectively (Figs. 4, 5). In contrast, the agreement in overall canopy cover estimates was high for images captured from 10 m flight height (0.82 ≤ R2 ≤ 0.94; Figs. 5, 6), except for one field (R2 = 0.34). They were, however, only moderate for images captured from an altitude of 50 m (0.18 ≤ R2 ≤ 0.89; not shown). For some sites, UAV-based vegetation cover estimates slightly over- or underestimate the actual value as derived from the high-resolution images. The apparent limitations of the benchmark method for estimation of vegetation cover thus highlight the need for improved methods.

Validation of the vegetation cover estimates based on UAV-based aerial images using very high resolution, ground-based images. (a) UAV-based aerial image of a reference area captured from an altitude of 10 m; (b) Corresponding binary vegetation-soil segmentation mask, with the area covered by the ground-based high-resolution image indicated by the red frame; (c) The registered segmentation mask of the ground-based, high-resolution image; (d) Composite image with the registered high-resolution image pasted into the corresponding aerial image. Metrics for the agreement between the two binary masks were done for the entire area covered by the high-resolution image, i.e., the area represented by the red rectangle in (b).

Overall agreement between estimates of vegetation cover obtained from ground-based high-resolution images and UAV-based aerial images captured from an altitude of 10 m. Data from all flights spanning the growth stages 20–54 were pooled at the field level. The dashed line represents the 1:1 line, the blue line represents the least squares line.

Usage Notes

Additional information, such as weather data to investigate plant growth35 or stress indicators36 can be obtained either from the Swiss Federal Office of Meteorology via idaweb or from agrometeo for numerous stations throughout Switzerland (see Table 2 for additional sources of potentially useful meta data). The data set is very rich in terms of different soil types, environmental conditions, wheat varieties and management practices, as well as lighting conditions at the time of measurement. Depending on the use case, this variability in the data set can be seen as both an advantage and a disadvantage. On the one hand, the data set can be considered as a representative sample of scenarios that would be encountered in practice7, enabling detailed analyses of method robustness. On-farm fields typically have a more complex history and management is more diverse than for fields located on research stations (e.g., types of machinery used). On the other hand, this may lead to cultivar-specific differences across fields that are confounded with differences in environmental (pedo-climatic) conditions across fields, and it may be challenging to disentangle these effects. Also, the data set covers winter wheat fields only, and extrapolation or generalization to other crops may be difficult. Depending on the flight height, the physical resolution may be insufficient for some applications. Especially at early growth stages, individual wheat leaves and young weed plants may be similar in size to a pixel. Mixed soil-plant pixels may therefore cause problems for analyses that focus on object shapes (see Fig. 4 in7 for an illustration). Yet, resolution is still much higher than in any satellite-derived product, while the area covered is still large enough to allow for comparisons with data from high-altitude platforms such as satellites. The original purpose of the data set was to create a broad basis for the development and validation of image-based methods for weed mapping in wheat fields. Accordingly, flights targeted the periods preceding complete canopy closure as well as late senescence, when we expected tall-growing weeds with a contrasting phenology to be discernible in dense canopies based on their color. Missing measurements around emergence in autumn and around heading and flowering may represent a limitation for certain use cases such as yield prediction.

Code availability

A detailed list of photogrammetric image processing steps within Agisoft Metashape Professional 1.5.2 (Agisoft LLC, St. Petersburg, Russia) was published previously7 and is freely available from the article website. Python code allowing to reproduce the results of the technical validation is open-sourced at https://github.com/and-jonas/wheat-field. Specifically, we share our methods for (i) image segmentation using pixel-wise color-based classification and deep-learning based segmentation for UAV and handheld images, respectively; (ii) retrieval of UAV images for specific sub-areas of interest on a field, such as the reference areas for which high-resolution images are available; (iii) downloading and filtering of the satellite data, and (iv) co-registration of high-resolution handheld images and UAV images to compare image processing outputs across scales. Thus, the code also illustrates how provided meta data can be used to subset images, for example.

References

Finger, R., Swinton, S. M., El Benni, N. & Walter, A. Precision farming at the nexus of agricultural production and the environment. Annual Review of Resource Economics 11, 313–335, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-resource-100518-093929 (2019).

Walter, A., Finger, R., Huber, R. & Buchmann, N. Smart farming is key to developing sustainable agriculture. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114, 6148–6150, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1707462114 (2017).

Basso, B. & Antle, J. Digital agriculture to design sustainable agricultural systems. Nature Sustainability 3, 254–256, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-020-0510-0 (2020).

Maes, W. H. & Steppe, K. Perspectives for remote sensing with unmanned aerial vehicles in precision agriculture. Trends in Plant Science 24, 152–164, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2018.11.007 (2019).

Torres-Sánchez, J., Peña, J. M., de Castro, A. I. & López-Granados, F. Multi-temporal mapping of the vegetation fraction in early-season wheat fields using images from UAV. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 103, 104–113, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2014.02.009 (2019).

Argento, F. et al. Site-specific nitrogen management in winter wheat supported by low-altitude remote sensing and soil data. Precision Agriculture ISSN: 1573-1618 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11119-020-09733-3 (2020).

Anderegg, J. et al. On-farm evaluation of UAV-based aerial imagery for season-long weed monitoring under contrasting management and pedoclimatic conditions in wheat. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 204, 107558, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.COMPAG.2022.107558 (2023).

Bendig, J. et al. Estimating biomass of barley using crop surface models (CSMs) derived from UAV-based RGB imaging. Remote Sensing 6, 10395–10412, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs61110395 (2014).

Rasmussen, J. et al. Pre-harvest weed mapping of cirsium arvense in wheat and barley with off-the-shelf UAVs. Precision Agriculture 20, 983–999, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11119-018-09625-7 (2019).

Roth, L. & Streit, B. Predicting cover crop biomass by lightweight UAS-based RGB and NIR photography: an applied photogrammetric approach. Precision Agriculture 19, 93–114, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11119-017-9501-1 (2018).

Aasen, H., Honkavaara, E., Lucieer, A. & Zarco-Tejada, P. J. Quantitative remote sensing at ultra-high resolution with UAV spectroscopy: A review of sensor technology, measurement procedures, and data correction workflows. Remote Sensing 10, 1091, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs10071091 (2018).

Yuan, L., Pu, R., Zhang, J., Wang, J. & Yang, H. Using high spatial resolution satellite imagery for mapping powdery mildew at a regional scale. Precision Agriculture 17, 332–348, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11119-015-9421-x (2016).

Perich, G. et al. Crop nitrogen retrieval methods for simulated sentinel-2 data using in-field spectrometer data. Remote Sensing 13, 2404, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs13122404 (2021).

Prey, L. & Schmidhalter, U. Simulation of satellite reflectance data using high-frequency ground based hyperspectral canopy measurements for in-season estimation of grain yield and grain nitrogen status in winter wheat. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 149, 176–187, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2019.01.023 (2019).

Stehman, S. V. & Foody, G. M. Key issues in rigorous accuracy assessment of land cover products. Remote Sensing of Environment 231, 111199, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2019.05.018 (2019).

Di Gennaro, S. F., Dainelli, R., Palliotti, A., Toscano, P. & Matese, A. Sentinel-2 validation for spatial variability assessment in overhead trellis system viticulture versus UAV and agronomic data. Remote Sensing 11, 2573, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11212573 (2019).

Alvarez-Vanhard, E., Corpetti, T. & Houet, T. UAV & satellite synergies for optical remote sensing applications: A literature review. Science of Remote Sensing 3, 100019, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.srs.2021.100019 (2021).

Madec, S. et al. VegAnn, vegetation annotation of multi-crop RGB images acquired under diverse conditions for segmentation. Scientific Data 10, 302, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-023-02098-y (2023).

Perich, G. et al. Pixel-based yield mapping and prediction from sentinel-2 using spectral indices and neural networks. Field Crops Research 292, 108824, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2023.108824 (2023).

Deines, J. M., Patel, R., Liang, S.-Z., Dado, W. & Lobell, D. B. A million kernels of truth: Insights into scalable satellite maize yield mapping and yield gap analysis from an extensive ground dataset in the US corn belt. Remote Sensing of Environment 253, 112174, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2020.112174 (2021).

Cai, Z., Jönsson, P., Jin, H. & Eklundh, L. Performance of smoothing methods for reconstructing NDVI time-series and estimating vegetation phenology from MODIS data. Remote Sensing 9, 1271, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs9121271 (2017).

Graf, L. V., Tschurr, F., Walter, A. & Aasen, H. Probabilistic assimilation of optical satellite data with physiologically based growth functions improves crop trait time series reconstruction. EarthArXiv https://doi.org/10.31223/X5596B (2023).

Schiefer, F., Schmidtlein, S. & Kattenborn, T. The retrieval of plant functional traits from canopy spectra through RTM-inversions and statistical models are both critically affected by plant phenology. Ecological Indicators 121, 107062, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ECOLIND.2020.107062 (2021).

Pinto, F., Zaman-Allah, M., Reynolds, M. & Schulthess, U. Satellite imagery for high-throughput phenotyping in breeding plots. Frontiers in Plant Science 14, 1114670, https://doi.org/10.3389/FPLS.2023.1114670/BIBTEX (2023).

Blasch, G. et al. The potential of UAV and very high-resolution satellite imagery for yellow and stem rust detection and phenotyping in Ethiopia. Scientific Reports 13, 1–19, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-43770-y (2023).

Jiang, J. et al. Combining UAV and sentinel-2 satellite multi-spectral images to diagnose crop growth and n status in winter wheat at the county scale. Field Crops Research 294, 108860, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2023.108860 (2023).

Leroux, C. & Tisseyre, B. How to measure and report within-field variability: a review of common indicators and their sensitivity. Precision Agriculture 20, 562–590, https://doi.org/10.1007/S11119-018-9598-X/FIGURES/3 (2019).

Lancashire, P. D. et al. A uniform decimal code for growth stages of crops and weeds. Annals of Applied Biology 119, 561–601, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-7348.1991.tb04895.x (1991).

Graf, L. V., Perich, G. & Aasen, H. EOdal: An open-source Python package for large-scale agroecological research using Earth Observation and gridded environmental data. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 203, 107487, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.COMPAG.2022.107487 (2022).

Anderegg, J. et al. UAV dataset of nine wheat fields in switzerland with raw, processed and meta data. https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000662770 (2024).

Roth, L. et al. Repeated multiview imaging for estimating seedling tiller counts of wheat genotypes using drones, https://doi.org/10.34133/2020/3729715 (2020).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 770–778, https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2016.90 (IEEE, 2023).

Zhou, Z., Siddiquee, M. M. R., Tajbakhsh, N. & Liang, J. UNet++: A nested u-net architecture for medical image segmentation, arXiv, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1807.10165 (2023).

Anderegg, J., Zenkl, R., Walter, A., Hund, A. & McDonald, B. A. Combining High-Resolution Imaging, Deep Learning, and Dynamic Modeling to Separate Disease and Senescence in Wheat Canopies. Plant Phenomics 5, 0053, https://doi.org/10.34133/PLANTPHENOMICS.0053 (2023).

Roth, L. et al. From Neglecting to Including Cultivar-Specific Per Se Temperature Responses: Extending the Concept of Thermal Time in Field Crops. Plant Phenomics 6, https://doi.org/10.34133/plantphenomics.0185 (2024).

Tschurr, F. et al. Frost Damage Index: The antipode of Growing Degree Days. Plant Phenomics 5, 0104, https://doi.org/10.34133/PLANTPHENOMICS.0104 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We thank Lukas Roth, Helge Aasen and Quirina Merz (all ETH Crop Science) for assistance in planning UAV flights and ground truth measurement campaigns, as well as Nicola Storni for technical assistance during data preparation. We would like to thank all farmers involved for providing us access to their wheat fields, for recording and sharing field management data, and for their cooperation in planning the measurement campaign. Funding was provided by ETH Zurich Foundation (project nr. 2020-FS-330) in the framework of a collaboration with Migros and IP Suisse. FT acknowledges funding of the Swiss National Science Foundation for the project “PHENOFLOW” (grant number 200756).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.W., B.S., J.A., and N.K. conceptualized the study and planned and coordinated the measurement campaigns. F.T., S.T., J.A., M.S., C.M., N.C., and B.S. carried out the measurements. S.T. established the protocol for photogrammetric image processing. S.T., J.A., and M.S. performed photogrammetric image processing. J.A., F.T., and N.K. implemented image analysis. L.V.G. assembled the satellite data. J.A. and F.T. performed technical validation, curated the data with assistance from NK, created the visualizations, and wrote the original draft of the manuscript. N.C., N.K., S.T., and L.V.G. reviewed and edited the original draft. A.W. and B.S. acquired project funding. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Anderegg, J., Tschurr, F., Kirchgessner, N. et al. Pixel to practice: multi-scale image data for calibrating remote-sensing-based winter wheat monitoring methods. Sci Data 11, 1033 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03842-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03842-8