Abstract

An extensive dataset consisting of adsorption energies of pernicious impurities present in biomass upgrading processes on common catalysts and support materials has been generated. This work aims to inform catalyst and process development for the conversion of biomass-derived feedstocks to fuels and chemicals. A high-throughput workflow was developed to execute density functional theory calculations for a diverse set of atomic (Al, B, Ca, Cl, Fe, K, Mg, Mn, N, Na, P, S, Si, Zn) and molecular (COS, H2S, HCl, HCN, K2O, KCl, NH3) species on 35 unique surfaces for transition-metal (Ag, Au, Co, Cu, Fe, Ir, Ni, Pd, Pt, Re, Rh, Ru) and metal-oxide (Al2O3, MgO, anatase-TiO2, rutile-TiO2, ZnO, ZrO2) catalysts and supports. Approximately 3,000 unique adsorption geometries and corresponding adsorption energies were obtained.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Biomass upgrading processes to produce bio-derived fuels and chemicals can help drive the decarbonization of historically petroleum-based industries. For example, biomass upgrading to produce drop-in biofuels can decarbonize hard-to-electrify forms of transportation, such as heavy-duty, rail, marine, and aviation vehicles1. Despite significant advances in developing commercially viable biomass conversion processes, these pathways still face several key challenges, including poor catalyst durability in the presence of real biomass feedstocks1,2,3,4. Both inorganic and organic impurities in biomass feedstocks can have deleterious effects on catalyst lifetime. Current research into mitigating the effects of these impurities is hindered by the wide range of impurities, catalysts, and supports that are utilized in biomass-upgrading chemistry and a poor understanding of the specific deactivating mechanisms2,3,4. High-throughput analyses based on density functional theory (DFT) can help address this research and development challenge, by providing information about the binding mode and strength of common biomass-derived impurities to catalysts and supports frequently used in biomass upgrading conversion processes.

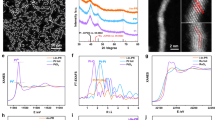

This work provides an extensive DFT dataset of the adsorption of the most common and/or pernicious catalyst impurities present in biomass upgrading processes, including many that are relevant to sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) production1,2. Specifically, adsorption modes and energies were evaluated for fourteen atomic (Al, B, Ca, Cl, Fe, K, Mg, Mn, N, Na, P, S, Si, Zn) and seven molecular (COS, H2S, HCl, HCN, K2O, KCl, NH3) species on unique high-symmetry sites for a range of transition-metal and metal-oxide surfaces representing commonly used catalysts or supports (Fig. 1). Based on their known stability, close-packed transition-metal surfaces were considered including (111) facets for face centered cubic (fcc) metals (Ag, Au, Cu, Ir, Ni, Pd, Pt, Rh); (0001) facets for hexagonal close packed (hcp) metals (Co, Re, Ru); and the (110) facet for the body centered cubic (bcc) metal Fe5,6,7. In addition, the role of undercoordinated sites on impurity adsorption was assessed for the fcc metals by considering open (100) and stepped (211) surfaces (Fig. 2). For metal-oxide materials, the most-stable facets were modelled based on prior assessments of surface stability, and include α-Al2O3(0001)8, MgO(100)9, anatase-TiO2(101)10, rutile-TiO2(110)11, ZnO(\(10\bar{1}0\))12,13, ZnO(\(11\bar{2}0\))12,13, and ZrO2(\(\bar{1}11\))14 (Fig. 3). By evaluating the adsorption of biomass-derived impurities on a wide range of transition-metal and metal-oxide catalyst surfaces, we aim to grow the breadth of data available to the catalyst and process development research community to accelerate the pace of research through enhanced understanding of the propensity of these impurities to poison common catalysts used in biomass upgrading processes.

The periodic table (Groups 1–6, lanthanides omitted) highlighting the metals, metal oxides, and adsorbates explored in this study, including 12 transition-metals and five metal-oxides, with 14 atomic and seven molecular impurities. Molecular species are indicated based on constituent elements other than C, H, O.

Top views of the α-Al2O3(0001), MgO(100), anatase-TiO2(101), rutile-TiO2(110), ZnO(\(10\bar{1}0\)), ZnO(\(11\bar{2}0\)), and ZrO2(\(\bar{1}11\)) surfaces with the unique high-symmetry sites labelled. Red spheres indicate O atoms and all other sphere colors indicate the respective metal atoms. Black lines denote the surface unit cell.

Methods

To generate the dataset, in total ca. 9,000 structure optimizations were performed to determine ca. 3,000 local- and global-minimum adsorption structures using the workflow depicted in Scheme 1. The procedure included (1) bulk material lattice optimization, (2) cleavage of the bulk structure to generate the desired surface facet, (3) generation of the slab supercell model, (4) determination of unique adsorption sites and geometries, (5) geometry optimization via DFT calculation, (6) identification of local minima states through comparison of energies corresponding to the optimized structures.

Workflow for generating optimized adsorption geometries and corresponding adsorption energies, beginning with the construction of the model surface. Approximately 9,000 initial adsorbate geometries were generated on transition-metal and metal-oxide surfaces to identify ca. 3,000 local- and global-minimum adsorption structures.

The DFT calculations were implemented using the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP 5.4.4)15,16. The exchange-correlation functional was approximated using the generalized-gradient approximation (GGA) through the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) exchange-correlation functional17. The D3 method developed by Grimme and co-workers was added to account for dispersion interactions18. Projector augmented-wave (PAW) potentials were used to describe electron-ion interactions19,20, and valence-electron wavefunctions were expanded through a plane-wave basis set with an energy cut-off of 400 eV. Spin-polarized adjustments to the GGA were implemented for all calculations. Ionic convergence occurred when the forces acting upon each atom were less than 0.02 eV/Å.

Impurity adsorption was evaluated on 12 transition metals (Ag, Au, Co, Cu, Ir, Ni, Pd, Pt, Re, Rh, and Ru) and five metal oxides (Al2O3, MgO, TiO2, ZnO, and ZrO2), selected based on their potential application as catalysts and/or supports in biomass-upgrading reactions. Unix- and Python-based scripts were developed to automate generation of input files for simulating the adsorption of impurities to each of the unique high-symmetry sites for each surface model. For the transition metals, the thermodynamically favoured close-packed surfaces were modelled with slab models composed of 4 atomic layers: (111) for fcc metals (Ag, Au, Cu, Ir, Ni, Pd, Pt, and Rh), (0001) for hcp metals (Co, Re, and Ru), and (110) for bcc metals (Fe). In addition, adsorption on the open (100) and stepped (211) surfaces was evaluated for the fcc metals. The fcc(111), fcc(100), hcp(0001), and bcc(110) surfaces were modelled through a (3 × 3) periodic surface unit cell, whereas the fcc(211) surfaces were simulated using a (1 × 3) periodic surface unit cell.

For the metal-oxide surfaces, the most-stable surface facets were employed for each material: α-Al2O3(0001) ((3 × 3 × 9) surface unit cell; Al-O3-R termination), MgO(100) ((3 × 3 × 4) surface unit cell), anatase-TiO2(101) ((3 × 3 × 12) surface unit cell; O-R termination), rutile-TiO2(110) ((3 × 3 × 8) surface unit cell; O-R termination), mixed-terminated ZnO(\(10\bar{1}0\)) and ZnO(\(11\bar{2}0\)) surfaces ((3 × 3 × 8) surface unit cells); and ZrO2(\(\bar{1}11\)) ((3 × 3 × 24) surface unit cell; O-R termination). Stoichiometric termination sequences are specified for metal-oxide facets that can exhibit different surface terminations. For example, the α-Al2O3(0001) surface was terminated with an Al-O3-R sequence, where R indicates the bulk ordering of the crystal structure in the z direction. For anatase-TiO2(101) ((Ueff,Ti = 2.5 eV)), rutile-TiO2(110) (Ueff,Ti = 2 eV), and ZrO2(\(\bar{1}11\)) (Ueff,Zr = 8 eV and Ueff,O = 4.35 eV), +U corrections were implemented utilizing the method by Dudarev et al. to account for on-site Coulombic repulsions21.

At least 10 Å of vacuum separated successive slabs in the z direction for all surface models. During geometry optimization, atoms in the top half of each surface model, including the middle layer for surfaces with an odd number of atomic layers, were allowed to fully relax while the atoms in the bottom half were fixed in their bulk-truncated positions. For the Ag and Au transition-metal surfaces, a 6 × 6 × 1 Monkhorst-Pack k-point mesh22 was used to sample the surface Brillouin zone, whereas a 4 × 4 × 1 Monkhorst-Pack k-point mesh was utilized for all other transition-metal surfaces as determined from convergence testing calculations. The Monkhorst-Pack k-point mesh used for the metal-oxide surfaces were: Al2O3(0001) – 4 × 4 × 1; MgO(100), anatase-TiO2(101), and rutile-TiO2(110) – 2 × 2 × 1; ZnO(\(10\bar{1}0\)) and ZrO2(\(\bar{1}11\)) – 2 × 1 × 1; and ZnO(\(11\bar{2}0\)) – 1 × 2 × 1.

Due to their larger size, KCl and K2O adsorption were modelled on (4 × 4) unit cells for the fcc(111), fcc(100), hcp(0001), bcc(110), and MgO(100) surface models, and (2 × 4) unit cells for the fcc(211) surface models. A 4 × 4 × 1 Monkhorst-Pack k-point mesh was used for the larger (4 × 4) Ag and Au surface unit cells. For all other surfaces, a 2 × 2 × 1 Monkhorst-Pack k-point mesh was used for K2O and KCl adsorption.

Adsorption on each surface model was limited to only one exposed side of the slab, with the required dipole correction applied to the electrostatic potential23. The adsorption strength of each impurity was quantified by its binding energy (EB), defined as:

where Etot, Eclean, and Egas are the total energy of the adsorbate + surface complex, clean surface, and adsorbate in the gas-phase, respectively. By this definition, a more negative binding energy corresponds to stronger adsorption and thus the possibility of a higher propensity for catalyst poisoning.

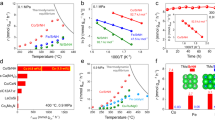

Only non-dissociative (molecular) adsorption configurations of molecular species were reported. The DDEC6 (density derived electrostatic and chemical)24 bond orders were calculated to distinguish elongated vs. dissociated intramolecular bonds of adsorbates; dissociatively adsorbed species were defined as having >75% reduction of intramolecular bond order from gas-phase values. Adsorption geometries of COS, K2O, and HCN were generated roughly parallel to the metal and metal-oxide surfaces. For HCl and KCl adsorption, both perpendicular and parallel adsorption geometries were identified. For H2S and NH3, geometries were generated for adsorption through S and N atoms, respectively. Structures were visualized with Atomic Simulation Environment (ASE) 3.22.125. Representative examples of converged geometries generated with Visualization for Electronic and Structure Analysis (VESTA)26 are depicted in Fig. 4. The range of adsorption energies computed for each impurity across the metal or metal-oxide surfaces evaluated are reported in Fig. 5.

Data Records

The converged adsorption structure (CONTCAR) and output files (OUTCAR) for each unique adsorption geometry and a JSON file of the complete, parsed dataset in the ChemCatBio Catalyst Property Database (CPD)27 data structure are provided in the Materials Cloud archive28. All unique local-minimum adsorption geometries for each adsorbate on each surface are included, and the global-minimum adsorption geometry on each surface is indicated in JSON via ‘is_most_stable_site.’ The Materials Cloud archive file structure for the structure and output files is organized hierarchically, beginning with surface (titled as surface_facet; e.g., Ag_100), followed by subdirectories for each atomic or molecular adsorbate (e.g., Al, HCl, N, etc.). For molecular species COS, HCl, HCN, K2O, and KCl, an additional subdirectory specifies the orientation of the bound molecule (diagonal (diag), left-right (lr), up-down (ud), side (side), or vertical (vert)). For all other adsorbates, subdirectories only specify the adsorption site of the adsorbate (e.g., top (t), bridge (b)) according to the site assignments defined in Figs. 1 and 2. A file detailing the directory structure is provided within the Materials Cloud Archive (README.txt). The output files can be viewed and adapted using any text editor and visualized using any common atomistic visualization software, such as ASE25 or VESTA26. The complete dataset, including all metadata, can also be searched and filtered and the results downloaded as a JSON within the ChemCatBio CPD.

Technical Validation

All bulk structures were validated prior to simulating adsorption of the impurity species via comparison of the optimized, computed bulk lattice constants with experimental literature values. The corresponding lattice constant values for metals (Table 1) and metal oxides (Table 2) show good agreement for all materials.

Adsorbed structures, including a retained molecular state for all molecular species, were confirmed via visualization of the corresponding structures and calculations of their respective bond orders as described in the Methods section. When available, the calculated adsorption energies are compared with previously reported values in the literature computed with identical or very similar (i.e., identical exchange-correlation functional and potentials) methods (Table 3). Comparable literature data for validation was identified for the more commonly studied atomic and molecular impurities, including S, H2S, N, NH3, and K. In most cases, the adsorption energies calculated in this work are within ±0.20 eV of the previously reported values. In cases where the values differ by more than 0.20 eV, including the largest discrepancy identified across the dataset (−0.45 eV) for H2S adsorption on Cu(111), the difference can likely be attributed to the inclusion of dispersion interactions in the calculations reported here resulting in a stronger predicted binding energy compared to the prior report. Additional differences between this work and data in the literature may be attributed to (i) inclusion of zero-point energy (ZPE) corrections in some other works, as ZPE corrections were not included in the dataset reported here and/or (ii) variations in surface coverage. Toward the latter, the comparison data obtained from the literature was limited to simulations at the clean-surface limit (i.e., sufficiently low coverage that lateral interactions should be insignificant), however we note that in some cases the specific coverage simulated was not clearly defined in the cited reference.

Code availability

No custom code is used.

References

Van Dyk, S., Su, J., Mcmillan, J. D. & Saddler, J. Potential synergies of drop‐in biofuel production with further co‐processing at oil refineries. Biofuels, Bioprod. Bioref. 13, 760–775 (2019). (John).

Lin, F. et al. Catalyst Deactivation and Its Mitigation during Catalytic Conversions of Biomass. ACS Catal. 12, 13555–13599 (2022).

Faizan, M. & Song, H. Critical review on catalytic biomass gasification: State-of-Art progress, technical challenges, and perspectives in future development. Journal of Cleaner Production 408, 137224 (2023).

Zhao, C. et al. Upgrading technologies and catalytic mechanisms for heteroatomic compounds from bio-oil – A review. Fuel 333, 126388 (2023).

Zhang, J.-M., Wang, D.-D. & Xu, K.-W. Calculation of the surface energy of hcp metals by using the modified embedded atom method. Applied Surface Science 253, 2018–2024 (2006).

Patra, A., Jana, S., Constantin, L. A., Chiodo, L. & Samal, P. Improved transition metal surface energies from a generalized gradient approximation developed for quasi two-dimensional systems. J. Chem. Phys. 152, 151101 (2020).

Tang, M. T., Ulissi, Z. W. & Chan, K. Theoretical Investigations of Transition Metal Surface Energies under Lattice Strain and CO Environment. J. Phys. Chem. C 122, 14481–14487 (2018).

Kurita, T., Uchida, K. & Oshiyama, A. Atomic and electronic structures of α-Al2O3 surfaces. Phys. Rev. B 82, 155319 (2010).

Mudiyanselage, K., Nadeem, M. A., Raboui, H. A. & Idriss, H. Growth, characterization, and stability testing of epitaxial MgO(100) on GaAs(100). Surface Science 699, 121625 (2020).

Zhang, B. et al. Formation and Evolution of the High-Surface-Energy Facets of Anatase TiO2. J. Phys. Chem. C 119, 6094–6100 (2015).

Diebold, U. The surface science of titanium dioxide. Surface Science Reports 48, 53–229 (2003).

Cooke, D. J., Marmier, A. & Parker, S. C. Surface Structure of (101̄0) and (112̄0) Surfaces of ZnO with Density Functional Theory and Atomistic Simulation. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 7985–7991 (2006).

Meyer, B. & Marx, D. Density-functional study of the structure and stability of ZnO surfaces. Phys. Rev. B 67, 035403 (2003).

Christensen, A. & Carter, E. A. First-principles study of the surfaces of zirconia. Phys. Rev. B 58, 8050–8064 (1998).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Computational Materials Science 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. The Journal of Chemical Physics 132, 154104 (2010).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Dudarev, S. L., Botton, G. A., Savrasov, S. Y., Humphreys, C. J. & Sutton, A. P. Electron-energy-loss spectra and the structural stability of nickel oxide: An LSDA+U study. Phys. Rev. B 57, 1505–1509 (1998).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188–5192 (1976).

Bengtsson, L. Dipole correction for surface supercell calculations. Phys. Rev. B 59, 12301–12304 (1999).

Manz, T. A. Introducing DDEC6 atomic population analysis: part 3. Comprehensive method to compute bond orders. RSC Adv. 7, 45552–45581 (2017).

Hjorth Larsen, A. et al. The atomic simulation environment—a Python library for working with atoms. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 29, 273002 (2017).

Momma, K. & Izumi, F. VESTA 3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data. J Appl Crystallogr 44, 1272–1276 (2011).

ChemCatBio Catalyst Property Database https://cpd.chemcatbio.org/ (2024).

Nolen, M. A., Tacey, S. A., Arellano-Treviño, M. A., Van Allsburg, K. M. & Farberow, C. A. High-throughput dataset of impurity adsorption on common catalysts in biomass upgrading applications. Materials Cloud https://doi.org/10.24435/MATERIALSCLOUD:KR-M2 (2024).

Soria, L. A., Zampieri, G. & Martiarena, M. L. Sulfur-Induced Reconstruction of Ag(111) Surfaces Studied by DFT. J. Phys. Chem. C 115, 9587–9592 (2011).

Wang, C. et al. Generalized-stacking-fault energy and twin-boundary energy of hexagonal close-packed Au: A first-principles calculation. Sci Rep 5, 10213 (2015).

Ono, F. & Maeta, H. Determination of Lattice Parameters in hcp Cobalt by Using X-ray Bond’s Method. J. Phys. Colloques 49, C8-63–C8-64 (1988).

Huš, M., Kopač, D. & Likozar, B. Catalytic Hydrogenation of Carbon Dioxide to Methanol: Synergistic Effect of Bifunctional Cu/Perovskite Catalysts. ACS Catal. 9, 105–116 (2019).

Milman, V. et al. Electronic structure, properties, and phase stability of inorganic crystals: A pseudopotential plane-wave study. Int. J. Quant. Chem. 77, 895–910 (2000).

Arblaster, J. W. Crystallographic Properties of Iridium. platin met rev 54, 93–102 (2010).

Nandi, P. K., Valsakumar, M. C., Chandra, S., Sahu, H. K. & Sundar, C. S. Efficacy of surface error corrections to density functional theory calculations of vacancy formation energy in transition metals. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 22, 345501 (2010).

Arblaster, J. W. Crystallographic Properties of Palladium. platin met rev 56, 181–189 (2012).

Ungerer, M. J., Santos-Carballal, D., Cadi-Essadek, A., Van Sittert, C. G. C. E. & De Leeuw, N. H. Interaction of H2O with the Platinum Pt (001), (011), and (111) Surfaces: A Density Functional Theory Study with Long-Range Dispersion Corrections. J. Phys. Chem. C 123, 27465–27476 (2019).

Palumbo, M. & Dal Corso, A. Lattice dynamics and thermophysical properties of h.c.p. Re and Tc from the quasi-harmonic approximation: Lattice dynamics and thermophysical properties of Re and Tc. Phys. Status Solidi B 254 (2017).

CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. (New York, 1996).

Arblaster, J. W. Crystallographic Properties of Ruthenium. Platin Met Rev 57, 127–136 (2013).

Lazarov, V. K. et al. Structure of the hydrogen-stabilized MgO (111) − (1 × 1) polar surface: Integrated experimental and theoretical studies. Phys. Rev. B 71, 115434 (2005).

Decremps, F. et al. Local structure of condensed zinc oxide. Phys. Rev. B 68, 104101 (2003).

Wang, D., Guo, Y., Liang, K. & Tao, K. Crystal structure of zirconia by Rietveld refinement. Sci. China Ser. A-Math. 42, 80–86 (1999).

Benamara, O., Snoeck, E., Respaud, M. & Blon, T. Growth of platinum ultrathin films on Al2O3(0001). Surface Science 605, 1906–1912 (2011).

Burdett, J. K., Hughbanks, T., Miller, G. J., Richardson, J. W. & Smith, J. V. Structural-electronic relationships in inorganic solids: powder neutron diffraction studies of the rutile and anatase polymorphs of titanium dioxide at 15 and 295 K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 109, 3639–3646 (1987).

Lee, J., Windus, T. L., Thiel, P. A., Evans, J. W. & Liu, D.-J. Coinage Metal–Sulfur Complexes: Stability on Metal(111) Surfaces and in the Gas Phase. J. Phys. Chem. C 123, 12954–12965 (2019).

Alfonso, D. R. First-principles studies of H2S adsorption and dissociation on metal surfaces. Surface Science 602, 2758–2768 (2008).

Liu, T.-W., Gorky, F., Carreon, M. L. & Gómez-Gualdrón, D. A. Energetics of Reaction Pathways Enabled by N and H Radicals during Catalytic, Plasma-Assisted NH3 Synthesis. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 10, 2034–2051 (2022).

Wang, Y.-X., Zhang, H.-L., Wu, H.-S. & Jia, J.-F. A density functional theory study of a water gas shift reaction on Ag(111): potassium effect. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 25, 768–777 (2023).

Wang, Y.-X. & Wang, G.-C. Water–Gas Shift Reaction over Au(111): The Effect of Potassium from a First-Principles-Based Microkinetic Model Analysis. J. Phys. Chem. C 126, 17579–17588 (2022).

Ko, J., Kwon, H., Kang, H., Kim, B.-K. & Han, J. W. Universality in surface mixing rule of adsorption strength for small adsorbates on binary transition metal alloys. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17, 3123–3130 (2015).

Rodriguez, J. A. et al. Water–Gas Shift Reaction on K/Cu(111) and Cu/K/TiO2 (110) Surfaces: Alkali Promotion of Water Dissociation and Production of H2. ACS Catal. 9, 10751–10760 (2019).

Li, H., Yang, W., Wu, C. & Xu, J. Origin of the hydrophobicity of sulfur-containing iron surfaces. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 23, 13971–13976 (2021).

Alfonso, D. R. Computational Studies of Experimentally Observed Structures of Sulfur on Metal Surfaces. J. Phys. Chem. C 115, 17077–17091 (2011).

Zhao, X. et al. Density functional study on H2S adsorption on Pd(111) and Pd/γ-Al2O3(110) surfaces. Applied Surface Science 423, 592–601 (2017).

Xie, T. et al. Synergistic Effects of Crystal Phase and Strain for N2 Dissociation on Ru(0001) Surfaces with Multilayered Hexagonal Close-Packed Structures. ACS Omega 7, 4492–4500 (2022).

Hinnemann, B. & Carter, E. A. Adsorption of Al, O, Hf, Y, Pt, and S Atoms on α-Al2O 3(0001). J. Phys. Chem. C 111, 7105–7126 (2007).

Zheng, H. et al. Theoretical design of transition metal-doped TiO2 for the selective catalytic reduction of NO with NH3 by DFT calculations. Catal. Sci. Technol. 12, 1429–1440 (2022).

Towns, J. et al. XSEDE: Accelerating Scientific Discovery. Comput. Sci. Eng. 16, 62–74 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was authored by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, operated by Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC, for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) under Contract No. DE-AC36-08GO28308. Funding provided by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, Bioenergy Technologies Office in collaboration with the Chemical Catalysis for Bioenergy (ChemCatBio) Consortium, a member of the Energy Materials Network (EMN). The views expressed in the article do not necessarily represent the views of the DOE or the U.S. Government. The U.S. Government retains and the publisher, by accepting the article for publication, acknowledges that the U.S. Government retains a nonexclusive, paid-up, irrevocable, worldwide license to publish or reproduce the published form of this work, or allow others to do so, for U.S. Government purposes. A portion of the research was performed using computational resources sponsored by the Department of Energy’s Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy and located at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory. This work also used in part the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE), which is supported by National Science Foundation grant number ACI-154856259, utilizing Expanse at the San Diego Supercomputer Center (SDSC), as well as Bridges-2 at the Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center (PSC), through allocation TG-CTS200042. M.A. Nolen thanks the Mines VPRTT Materials Science Graduate Fellowship Program funded by the National Science Foundation award (OAC 2118201).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The computational dataset was generated and parsed by S. A. Tacey with a subset generated by M.A. Nolen and C.A. Farberow. M.A. Arellano-Trevino and M.A. Nolen compiled literature data for technical validation. The manuscript was written by M.A. Nolen, S.A. Tacey, and C.A. Farberow with review by all other authors. K.M. Van Allsburg, S.A. Tacey, and C.A. Farberow were responsible for conceptualization of the scope of work. K.M. Van Allsburg and C.A. Farberow acquired the supporting funding.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nolen, M.A., Tacey, S.A., Arellano-Treviño, M.A. et al. High-throughput dataset of impurity adsorption on common catalysts in biomass upgrading applications. Sci Data 11, 1049 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03872-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03872-2