Abstract

The human thermal stress indices and datasets are vital for promoting public health and reducing negative environmental impacts as global climate change and extreme meteorological events increase. The current thermal indices generally use an instantaneous or average value to describe thermal stress which cannot reflect the distribution of thermal comfort conditions over time, and there are no global-scale thermal stress datasets with both 0.1° or higher spatial resolution and hourly temporal resolution available yet. A novel human thermal metric, Thermal Stress Duration (TSD), is proposed to represent the accumulative time of different thermal stress levels within a certain period. A high temporal resolution global gridded dataset of human thermal stress metrics (HiGTS) is presented, which consists of hourly gridded maps of Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI), Universal Thermal Stress (UTS), and daily TSD at 0.1° × 0.1° spatial resolution over the global land surface, spanning from January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2023.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Extreme meteorological events such as heatwaves and cold spells occur frequently and globally, and cause increased mortality risks in recent decades1,2,3. These events usually last for several days or weeks but lead to significant impacts on daily life and health4,5,6. Global gridded datasets of human thermal stress metrics with high temporal resolution (hourly, daily) can continuously monitor the entire process of extreme meteorological events in time and space, playing a crucial role in public health, sports, outdoor work, and tourism7,8,9,10.

The Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI) is a multivariate parameter describing the synergistic heat exchanges between the thermal environment and the human body10,11. It assesses the outdoor thermal environment for biometeorological applications by simulating the dynamic physiological response with a model of human thermoregulation coupled with a temperature-adaptive clothing insulation model12,13,14. Due to its comprehensive and physiologically-based approach, integration of various environmental factors, and dynamic thermal response, the UTCI is capable of assessing thermal comfort across different climatic conditions and has been validated through extensive research, demonstrating its reliability and effectiveness in a variety of climates, temporal and spatial scales15,16,17.

The state-of-the-art datasets that contain the UTCI, such as ERA5-HEAT10, HiTiSEA8, Heat Metrics for US Counties18, and GloUTCI-M19, have their characteristics and advantages. The ERA5-HEAT is a global gridded historical dataset of human thermal comfort indices from ECMWF Reanalysis v5 (ERA5). It consists of hourly Mean Radiant Temperature (MRT) and UTCI from 1979 to present with 0.25° × 0.25° spatial resolution at the global scale (except for Antarctica). The HiTiSEA, derived from the ERA5-Land and ERA5 reanalysis products, is a high-spatial-resolution daily dataset of human thermal stress indices that contains 3 types of UTCI indices, MRT metrics, and eight other empirical thermal indices from 1981 to 2019, with a spatial resolution of 0.1° × 0.1°over South and East Asia. The Heat Metrics for US Counties created by Keith et al. is a database of population-weighted, spatially explicit daily Wet Bulb Globe Temperature (WBGT), UTCI, other and heat metrics for counties in the conterminous United States derived from the ERA5-Land. GloUTCI-M is monthly UTCI dataset produced by leveraging advanced machine learning models and multiple data sources including global meteorological station data and seven covariates. It spans from March 2000 to October 2022 with a high spatial resolution of 1 km over global land coverage making it a valuable resource for climate change and meteorological science, but the temporal resolution of monthly limits its application to meteorological events. These datasets either have a relatively low spatial or temporal resolution, or do not cover global scales, and there are no global-scale thermal stress datasets with both 0.1° or higher spatial resolution and hourly temporal resolution available yet. Considering ERA5-Land is a state-of-the-art reanalysis dataset that covers the land surface of the entire globe at 0.1° × 0.1° spatial resolution and 1 h temporal resolution, it is achievable to produce hourly UTCI dataset with a high spatial resolution of 0.1° × 0.1°over the global land surface.

The current thermal indices generally use an instantaneous or average value such as temperature to describe thermal comfort and grade thermal stress. The instantaneous value cannot reflect the thermal comfort situation over time, and the average value may introduce some bias, especially in the case of frequent and drastic changes in thermal stress, where the thermal comfort is lower, but the average value would indicate a more comfortable situation. Furthermore, compared to instantaneous thermal stress, frequent or long-lasting extreme thermal conditions such as heatwaves and cold spells are more likely to cause the failure of human thermoregulatory mechanisms, and have severe impacts on human health, society, and economic productivity5,20,21. Stable and comfortable conditions with no thermal stress, on the contrary, are essential for liveability, health, well-being, and social cohesion22,23. Therefore, the duration of thermal stress can be an important indicator to describe human thermal stress and measure whether a place is comfortable or liveable.

A new thermal metric named Thermal Stress Duration (TSD) is proposed and defined as the accumulative time (hours, for example) of different thermal stress levels within a certain period (daily, monthly, yearly, etc.). It is widely applicable for any thermal stress indices which can be categorized into multiple thermal stress levels such as UTCI and WBGT. In this dataset, the TSD is calculated from UTCI levels and contains ten variables that comply with the UTCI categories in terms of thermal stress24 (Check the Methods section for details). The units of TSD are hours (h).

Derived using climate variables from ERA5-Land and ERA5, this paper presents a high temporal resolution global gridded dataset of human thermal stress metrics (HiGTS), which consists of hourly gridded maps of UTCI, Universal Thermal Stress (UTS), and daily TSD at 0.1° × 0.1° spatial resolution over the global land surface, spanning from January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2023. This high spatiotemporal resolution dataset will be a great help for promoting public health, safeguarding human activities, reducing negative environmental impacts per capita, and evaluating livability.

Methods

Data source

The meteorological variables used to compute the HiGTS dataset include solar radiation fluxes, thermal radiation fluxes, air temperature, dewpoint temperature, and wind speed, which are all retrieved from the ERA5-Land and ERA5 datasets, as shown in Table 1. ERA5 is the fifth generation ECMWF reanalysis product with a horizontal resolution of 0.25° × 0.25° and temporal resolution of 1 h from 1940 to present25,26. By replaying the land component of the ECMWF ERA5 climate reanalysis, ERA5-Land provides a consistent view of the evolution of land variables at an enhanced horizontal resolution of 0.1° × 0.1° and a temporal resolution of 1 h from 1950 to present27. Compared with other reanalysis products such as the Modern-Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications version 2 (MERRA-2)28, the NCEP Climate Forecast System Reanalysis (CFSR)29, the Japanese 55-year Reanalysis (JRA-55)30 and the Global Land Data Assimilation System (GLDAS)31, the ERA5 and ERA5-Land datasets have finest horizontal and temporal resolution, and contain all the requisite variables to compute the UTCI, especially solar and thermal radiation fluxes.

The calculation of UTCI requires four input parameters: air temperature (Ta), mean radiant temperature (MRT), wind speed, and humidity24. The solar and thermal radiation fluxes (ssrd, ssr, fdir, strd and str) are the variables necessary for the calculation of the MRT32 which is used to assess the impact of radiation fluxes on the energy balance of human beings. Since the fdir in ERA5 has a coarser horizontal resolution than other variables in ERA5-Land, it is regraded to 0.1° × 0.1° using nearest-neighbour interpolation method following the approach of Yan et al.8. The wind speed can be calculated from the two components of the 10 m wind (Vu and Vv). The humidity is expressed as water vapor pressure or relative humidity. The ERA5-Land provides 2 m dewpoint temperature (Td) instead of relative humidity as a measure of the humidity of the air, and the dewpoint temperature will be converted to water vapor pressure for calculating UTCI.

Calculation of metrics

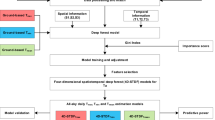

This HiGTS dataset provides three metrics: hourly UTCI, hourly UTS, and daily TSD. The data processing procedure is shown in Fig. 1. These metrics were calculated by GPU-accelerated computing with a python package HiGTS_src which can be used to replicate the entire calculations for this dataset.

UTCI

As calculating the UTCI by running the original thermoregulation model could be too time-consuming for a high spatial and temporal resolution global gridded dataset, this paper calculated UTCI following the approach of Di Napoli et al.10, which uses the operational procedure to compute the offset between the UTCI and Ta via a six-order polynomial regression approximation24. The simple form of the procedure to calculate UTCI in degrees Celsius (°C) is written as follows:

Where Ta is the 2 m air temperature (°C), MRT is the mean radiant temperature (°C), Va is the 10 m wind speed (m/s), the root of the sum of squares of Vu and Vv, and Pa is the water vapor pressure (hPa). The MRT and Pa were calculated from the meteorological variables following the functions used in the HiTiSEA dataset8,33:

where σ is the Stefan Boltzmann constant (5.67 × 10−8 W m−2 K−4), αir is the absorption coefficient of the body surface area irradiated by solar radiation (standard value 0.7), εp is the emissivity of the clothed human body (standard value 0.97), fp is the projected area factor which is a function of the solar zenith angle (θ), and fa is the solid angle of the land surface and the sky (set to 0.5). Sdir, Sdiff, Sup, Ldn, Lup are the anisotropic direct shortwave radiation flux, diffuse shortwave radiation flux, upwelling (surface reflected) shortwave radiation flux, downwelling longwave radiation flux, and upwelling longwave radiation flux, respectively, and all expressed in watts per square meter (W m−2). The units of the solar radiation fluxes (ssrd, ssr, fdir) and thermal radiation fluxes (strd, str) from ERA5-Land and ERA5 are joules per square meter (J m−2), thus these variables should be divided by the accumulation period (1 hour) expressed in seconds to convert to W m−2. Tdc is the dewpoint temperature in degrees Celsius (°C) which should be converted from dewpoint temperature (Td) in Kelvin by subtracting 273.15.

UTS

According to the UTCI equivalent temperatures categorized in terms of thermal stress24, a thermal metric named Universal Thermal Stress (UTS) was calculated from UTCI. As shown in Table 2, the UTCI is divided into 10 categories to indicate different thermal stress, and each category is assigned an abbreviation and a UTS value (from −5 to 4) which will be used to calculate the Thermal Stress Duration.

TSD

The TSD is the accumulative hours of different thermal stress values within a certain period and contains ten variables. For each thermal stress category c and its value vc

the corresponding TSDc is calculated as follows:

where n is the given period (hours) and \({{UTS}}_{k}{|k}=(\mathrm{1,2},\ldots n)\) is the hourly UTS during the period. For daily TSD, the period n = 24. The TSDc is the total number where the UTS is equal to the value of current category c, and the sum of the ten TSDc is equal to the given total hours.

Data Records

The HiGTS dataset consists of hourly UTCI, UTS, and daily TSD at 0.1° × 0.1° spatial resolution over the global land surface. It currently spans from January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2023. Individual thermal stress indices were aggregated into a single NetCDF file on a daily basis, which is named as follows:

where Metric is the thermal stress metric name, YYYYMMDD is the date of the daily file. All the indices and variables in the HiGTS dataset are listed in Table 3. It should be noted that the fill value of UTCI is equal to 9.969209968386869e + 36, the default fill value of the datatype ‘f4’ (32-bit floating point) in the netCDF4 package34.

The HiGTS dataset contains 26298 NetCDF files with a total volume of 1.24TB, and it is available and free to download via the figshare repository35. Due to the repository capacity limitations, the files are put in one package every three months named after:

where YYYY is the year, X (X = 1,2,3,4) is the package index of the year (s1 for months: 1–3, s2 for months: 4–6, s3 for months: 7–9, and s4 for months: 10–12). For example, the package named \({HiGTS\_}2023s4.\,{tar}.\,{gz}\) contains the data from October 1, 2023 to December 31, 2023.

Technical Validation

Data precision control

This dataset implements data precision control throughout the entire process: source data acquisition, variable calculation, and data storage. The source data are retrieved from the ECMWF ERA5-Land and ERA5 reanalysis datasets which combine model data with observations from across the world into a globally complete and consistent dataset using the laws of physics26,36. The variables were downloaded from the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS)25,27 in the official GRIB file format to ensure the accuracy of input data rather than the experimental NetCDF file format. The GRIB files store data in float type while the NetCDF files generated by the data repository store data in short type and use a scale factor to compress the data which will result in cumulative losses. The variables in the HiGTS dataset were calculated using floating-point operations, and the UTCI and intermediate variables are stored in float type to prevent the loss of data accuracy.

Comparison with existing UTCI datasets

This HiGTS dataset was technically compared with two other high temporal resolution datasets of human thermal stress: the HiTiSEA dataset with daily UTCI at 0.1° × 0.1° spatial resolution, and the ERA5-HEAT dataset with hourly UTCI at 0.25° × 0.25° spatial resolution. A summary table that details the existing state-of-the-art datasets and the HiGTS dataset is shown in Table S1.

The HiTiSEA dataset covers the area of South and East Asia (65°–155°E, 3°–58°N), and spans from January 3, 1981, to December 31, 2019. Thus, the HiGTS was clipped to the South and East Asia region, as shown in Fig. 2, so that these two datasets could be compared on the same spatial and temporal scales, covering the area of South and East Asia and spanning from January 1 to December 31, 2019 (365 days). The daily mean values of UTCI in HiGTS were calculated to compare with the UTCI_mean variable in HiTiSEA at the grid (pixel) scale. The results show that the HiGTS and HiTiSEA have almost identical values for the South and East Asian regions with RMSE below 0.2 °C and bias below 0.09 °C.

The ERA5-HEAT dataset covers the global area except for Antarctica (90N-60S, 180W-180E) from 1979 to the present. Due to differences in spatial resolution, the UTCI files in ERA5-HEAT were scaled to 0.1° × 0.1° using the nearest-neighbor interpolation method so that all overlapping grids in HiGTS can be considered. Sample UTCI data for T00 UTC on December 31, 2019, is shown in Fig. 3. The hourly UTCI variables in the two datasets were compared at grid scale from January 1 to December 31, 2019 (8760 hours). The RMSE and bias of UTCI variable were recorded, and the percentage histograms of RMSE and bias were plotted in Fig. 4 where the x-axis represents the value of RMSE or bias and the unit is °C, the y-axis represents the number of grids with the same value of RMSE or bias as a percentage of the total number of grids on the land (overlapping area in the spatial extent of the two datasets). The results show that the average RMSE and bias of HiGTS and ERA5-HEAT are 1.79 °C and 0.77 °C, respectively. The percentage of grids with an RMSE below 5 °C is more than 98.84%, and that with a bias below 5 °C is more than 99.50%.

Comparison against observations

The HiGTS was compared against observations from the global hourly meteorological stations of the Integrated Surface Database (ISD) provided by the National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI)37. To be chronologically consistent with the above comparisons with existing datasets, and ensure validity and representativeness, the data files in 2019 were selected and processed on the following conditions:

-

stations with spatial overlap with UTCI data (over global land coverage)

-

records with valid wind speed, air temperature, and dew point temperature values, and the range of values meets the requirements for calculating UTCI

-

records were averaged if there were multiple records in an hour

-

stations with records exceeding 300 days and 7200 hours

Eventually, more than 76 million valid records from 5299 stations were used for comparison with the HiGTS dataset. The hourly UTCI values for ISD stations were calculated by the thermofeel38, a Python thermal comfort indices library that has been implemented into the operational weather forecasting systems at ECMWF and used to produce UTCI in the Heat Metrics for US Counties database. The spatial distribution, percentage histograms of hourly UTCI RMSE and bias for HiGTS and ISD stations in 2019 are shown in Figs. 5, 6. The results show that the average RMSE and bias of HiGTS and ISD stations are 3.93 °C and −0.65 °C, respectively. The percentage of stations with an RMSE below 6 °C is 91.19%, and that with a bias below 5 °C is 95.57%. Cold regions with high latitude or altitude usually have greater differences in UTCI than other regions. The difference in wind speed has the greatest impact on the variation of UTCI, with a Pearson coefficient of 0.86, followed by air temperature and dew point temperature.

The RMSE of hourly UTS for HiGTS and ISD stations in 2019 was calculated and mapped in Fig. 7(a). Compared with UTCI, the differences in UTS between HiGTS and ISD stations are much smaller with 62.79% of the stations having the same thermal stress value and 99.43% of them having a difference within 1. It proves that metrics classified by numerical values have better robustness across datasets.

The maximum value of TSD (Statistical TSD mode) represents the longest-lasting thermal stress state at a given location. The greater the difference between it and the heat stress of average temperature or UTCI, the less the average values can reflect the comfort conditions at that location. By comparing the TSD mode of HiGTS with the thermal stress values of the annual average UTCI of ISD stations in 2019, as mapped in Fig. 7(b), stations with a large difference between TSD mode and UTCI mean are usually located in high latitudes and cold regions. Five stations in the 1st Köppen-Geiger climate class39,40 were selected to calculate and plot the percentage of TSD variables (Blue line) and the thermal stress of the UTCI mean (red dashed line) in 2019, as shown in Fig. 8. The results suggest that as an indicator composed of multiple variables and a cumulative quantity over time, TSD provides a more comprehensive picture of the distribution in different heat stress levels than instantaneous or average values, especially in regions with large differences in hot and cold sensations.

Usage Notes

Instructions to access the HiGTS dataset

The HiGTS dataset is available and free to download via the figshare repository (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.c.6948135)35. Please note that the files are put in one package every three months (four packages for one year), and there are a total of 96 data packages and one code package. If researchers need the data before 2000 or after 2023, please download the source codes and produce them by following the usage notes.

The NetCDF files can be read by a variety of software (Panoply, MATLAB, QGIS, ArcGIS, etc.) and programs (Python, R, etc.). If researchers read the files through programming, please pay attention to the fill values of the variables, as shown in Table 3. We recommend the netCDF4-Python package to read the NetCDF files.

Thermal stress anomaly in the Northern Hemisphere in July 2023: a showcase

Reports and research have proved that the summer of 2023 was the hottest on record, and heat waves and hot extremes occurred simultaneously in the Northern Hemisphere in July 202341,42. Here we present an example to demonstrate how the HiGTS dataset can be used to assess the thermal stress anomaly in the Northern Hemisphere in July 2023 relative to 2000–2022.

The steps for data acquisition and processing are as follows:

-

download July data from the repository for 2000 – 2023, i.e., the packages named \({HiGTS\_}20{MMs}3.\,{tar}.\,{gz}\) \(({MM}=00,\,01,\,\ldots ,\,23)\)

-

for each July, calculate the monthly UTCI_mean from hourly UTCI, and the monthly TSD (sum of 31 days, ten variables)

-

calculate the average monthly UTCI_mean and TSD for July from 2000 to 2022

-

calculate the UTCI_mean and TSD anomaly in July 2023 relative to 2000 – 2022

-

sum the four heat stress variables (mhs, shs, vshs, ehs) in the TSD anomaly

-

clip the results to the Northern Hemisphere and draw maps

The hot extremes in July 2023 resulted in high heat stress anomalies across most of the Northern Hemisphere, including North America, Africa, Central and North Asia, and the Mediterranean Rim, as shown in Fig. 9. Anomalies in heat stress duration are more pronounced and more widely distributed, especially at low latitudes, such as Central America, West Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Central Indian Mountain area.

As a multivariate metric, TSD can help to detect changes and assess the impacts of thermal stress at a finer scale. The duration anomalies of four heat stress variables (mhs, shs, vshs, ehs) are shown in Fig. 10, and they vary spatially. The hot extremes are generally associated with an increase in the duration of moderate heat stress. Increases in the duration of very strong heat stress occur mainly in the southern United States, northern Mexico, Mediterranean Rim, and central Africa. Increases in the duration of extreme heat stress occur mainly in the Sahara Desert in Africa and the Sonora Desert in North America.

Applicable conditions and limitations

Although the UTCI can be applied in different climates and spatiotemporal scales, the applicable conditions and limitations of these metrics in the HiGTS dataset should be noted:

-

the operational procedure for UTCI is valid within specific input ranges (MRT, air temperature, humidity, and wind speed)24, the accuracy may decrease in areas with complex or variable meteorological conditions, such as strong winds, high altitude, heterogeneous landscapes, etc.

-

Although the hourly metrics can provide a more detailed assessment of the thermal stress, short periods of thermal stress levels may not reflect the real thermal satiations, for example, the lowering of summer night temperatures may bring about a brief state of no thermal stress, but that doesn’t mean it reduces the risk to human body from prolonged heat stress at hot nights43. This is why we propose the concept of TSD to evaluate thermal stress and its effects on humans from a longer time scale

-

The accuracy of the dataset can also be affected by the uncertainty of the input reanalysis variables, for example, the accuracy difference associated with the altitude, underlying surface, distance to the coastline, etc36,44. The dataset should be used in combination with the uncertainty of the ERA5 and ERA5-Land datasets

Code availability

A Python package named HiGTS_src was developed to calculate the high-resolution global gridded dataset of human thermal stress indices. This Python package uses GPU-accelerated computation based on CUTCI45 to produce our HiGTS dataset and some required variables. The source codes, requirements, and usage notes are included in the package which is available via figshare35.

References

Calvin, K. et al. IPCC, 2023: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, H. Lee and J. Romero (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland. https://doi.org/10.59327/IPCC/AR6-9789291691647 (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), 2023).

Perkins-Kirkpatrick, S. E. & Lewis, S. C. Increasing trends in regional heatwaves. Nat Commun 11, 3357, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16970-7 (2020).

Gao, Y. et al. Global, regional, and national burden of mortality associated with cold spells during 2000–19: a three-stage modelling study. The Lancet Planetary Health 8, e108–e116, https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(23)00277-2 (2024).

Hassan, W. U., Nayak, M. A. & Azam, M. F. Intensifying spatially compound heatwaves: Global implications to crop production and human population. Sci Total Environ 932, 172914, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.172914 (2024).

Wang, L. et al. The impact of cold spells on mortality and effect modification by cold spell characteristics. Sci Rep-Uk 6, 38380, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep38380 (2016).

Xu, Z., FitzGerald, G., Guo, Y., Jalaludin, B. & Tong, S. Impact of heatwave on mortality under different heatwave definitions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Int 89-90, 193–203, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2016.02.007 (2016).

Zhang, H. et al. HiTIC-Monthly: a monthly high spatial resolution (1 km) human thermal index collection over China during 2003–2020. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 15, 359–381, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-15-359-2023 (2023).

Yan, Y., Xu, Y. & Yue, S. A high-spatial-resolution dataset of human thermal stress indices over South and East Asia. Scientific Data 8, 229, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-021-01010-w (2021).

Mistry, M. N. A High Spatiotemporal Resolution Global Gridded Dataset of Historical Human Discomfort Indices. Atmosphere 11, 835, https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos11080835 (2020).

Di Napoli, C., Barnard, C., Prudhomme, C., Cloke, H. L. & Pappenberger, F. ERA5-HEAT: A global gridded historical dataset of human thermal comfort indices from climate reanalysis. Geoscience Data Journal 8, 2–10, https://doi.org/10.1002/gdj3.102 (2021).

Blazejczyk, K. et al. An introduction to the Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI). Geographia Polonica 86, 5–10, https://doi.org/10.7163/GPol.2013.1 (2013).

Jendritzky, G., de Dear, R. & Havenith, G. UTCI—Why another thermal index? International Journal of Biometeorology 56, 421–428, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-011-0513-7 (2012).

Havenith, G. et al. The UTCI-clothing model. International Journal of Biometeorology 56, 461–470, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-011-0451-4 (2012).

Fiala, D., Havenith, G., Bröde, P., Kampmann, B. & Jendritzky, G. UTCI-Fiala multi-node model of human heat transfer and temperature regulation. International Journal of Biometeorology 56, 429–441, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-011-0424-7 (2012).

Zare, S. et al. Comparing Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI) with selected thermal indices/environmental parameters during 12 months of the year. Weather and Climate Extremes 19, 49–57, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wace.2018.01.004 (2018).

Wu, J. K. et al. The Variation of UTCI with the Background of Climate Change and Its Implications for Tourism in a Complicated Climate Region in Western China. Sustainability-Basel 14 https://doi.org/10.3390/su142215047 (2022).

Blazejczyk, K., Epstein, Y., Jendritzky, G., Staiger, H. & Tinz, B. Comparison of UTCI to selected thermal indices. International Journal of Biometeorology 56, 515–535, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-011-0453-2 (2012).

Spangler, K. R., Liang, S. & Wellenius, G. A. Wet-Bulb Globe Temperature, Universal Thermal Climate Index, and Other Heat Metrics for US Counties, 2000–2020. Scientific Data 9, 326, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01405-3 (2022).

Yang, Z. et al. GloUTCI-M: a global monthly 1 km Universal Thermal Climate Index dataset from 2000 to 2022. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 16, 2407–2424, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-16-2407-2024 (2024).

Matthews, T. K. R., Wilby, R. L. & Murphy, C. Communicating the deadly consequences of global warming for human heat stress. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114, 3861–3866, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1617526114 (2017).

Vecellio, D. J., Kong, Q., Kenney, W. L. & Huber, M. Greatly enhanced risk to humans as a consequence of empirically determined lower moist heat stress tolerance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 120, e2305427120, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2305427120 (2023).

S, M. & Rajasekar, E. Evaluating outdoor thermal comfort in urban open spaces in a humid subtropical climate: Chandigarh, India. Build Environ 209, 108659, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2021.108659 (2022).

Yan, T., Jin, H. & Jin, Y. The mediating role of emotion in the effects of landscape elements on thermal comfort: A laboratory study. Build Environ 233, 110130, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2023.110130 (2023).

Bröde, P. et al. Deriving the operational procedure for the Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI). International Journal of Biometeorology 56, 481–494, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-011-0454-1 (2012).

Hersbach, H. et al. ERA5 hourly data on single levels from 1940 to present. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS) https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.adbb2d47 (2023).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q J Roy Meteor Soc 146, 1999–2049, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.3803 (2020).

Muñoz Sabater, J. ERA5-Land hourly data from 1950 to present. https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.e2161bac (2019).

Gelaro, R. et al. The Modern-Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications, Version 2 (MERRA-2). Journal of Climate 30, 5419–5454, https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-16-0758.1 (2017).

Saha, S. et al. The NCEP Climate Forecast System Reanalysis. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 91, 1015–1058, https://doi.org/10.1175/2010BAMS3001.1 (2010).

Harada, Y. et al. The JRA-55 Reanalysis: Representation of Atmospheric Circulation and Climate Variability. Journal of the Meteorological Society of Japan. Ser. II 94, 269–302, https://doi.org/10.2151/jmsj.2016-015 (2016).

Rodell, M. et al. The Global Land Data Assimilation System. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 85, 381–394, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-85-3-381 (2004).

Di Napoli, C., Hogan, R. J. & Pappenberger, F. Mean radiant temperature from global-scale numerical weather prediction models. Int J Biometeorol 64, 1233–1245, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-020-01900-5 (2020).

Yan, Y., Xu, Y. & Yue, S. A High-spatial-resolution Dataset of Human Thermal Stress Indices over South and East Asia. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.c.5196296 (2021).

Unidata/netcdf4-python: version 1.6.3 release https://zenodo.org/records/7702052 (Zenodo, 2023).

Jian, H. et al. HiGTS: A high temporal resolution global gridded dataset of human thermal stress metrics. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.c.6948135 (2024).

Muñoz-Sabater, J. et al. ERA5-Land: a state-of-the-art global reanalysis dataset for land applications. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 4349–4383, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-13-4349-2021 (2021).

National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI). Global Hourly - Integrated Surface Database (ISD) https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/products/land-based-station/integrated-surface-database (2021).

Brimicombe, C. et al. Thermofeel: A python thermal comfort indices library. SoftwareX 18, 101005, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.softx.2022.101005 (2022).

Peel, M. C., Finlayson, B. L. & McMahon, T. A. Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 11, 1633–1644, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007 (2007).

Beck, H. E. et al. Present and future Köppen-Geiger climate classification maps at 1-km resolution. Scientific Data 5, 180214, https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2018.214 (2018).

Hegerl, G. C. & Taylor, K. L. Last year’s summer was the warmest in 2,000 years. Nature 631, 35–36, https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-02057-6 (2024).

Zhang, W. et al. 2023: Weather and Climate Extremes Hitting the Globe with Emerging Features. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 41, 1001–1016, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00376-024-4080-3 (2024).

Royé, D. et al. Effects of Hot Nights on Mortality in Southern Europe. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass.) 32, 487–498, https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0000000000001359 (2021).

Zou, J. et al. Performance of air temperature from ERA5-Land reanalysis in coastal urban agglomeration of Southeast China. Sci Total Environ 828, 154459, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.154459 (2022).

Jian, H. et al. CUTCI: A GPU-Accelerated Computing Method for the Universal Thermal Climate Index. Ieee Geosci Remote S 21, 1–5, https://doi.org/10.1109/LGRS.2024.3378696 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Director Fund of the International Research Center of Big Data for Sustainable Development Goals under Grant No. CBAS2022DF015, and the National Key Research and Development Program of China under Grant No. 2022YFC3800704. The authors would like to thank Dr. Yechao Yan and Dr. Chloe Brimicombe for providing the origin code of HiTiSEA and thermofeel. We also thank the ECMWF for the family of ERA5 and ERA5-Land datasets.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Hongdeng Jian: conceptualization, methodology, software and funding acquisition; Zhenzhen Yan: methodology and writing; Xiangtao Fan: review, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition; Qin Zhan: data curation and writing; Chen Xu: software and data curation; Weijia Bei: data acquisition and preprocessing; Jianhao Xu: data management and validation; Mingrui Huang: background research and analysis; Xiaoping Du: advisor and review; Junjie Zhu: review; Zhimin Tai: data validation; Jiangtao Hao: mapping; Yanan Hu: software.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jian, H., Yan, Z., Fan, X. et al. A high temporal resolution global gridded dataset of human thermal stress metrics. Sci Data 11, 1116 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03966-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03966-x

This article is cited by

-

A Global High-Resolution Comprehensive Heat Indices Dataset from 1950 to 2024

Scientific Data (2026)

-

A Human-Centered Framework for Assessing Socio-Thermal Vulnerability in Climate-Vulnerable Region of Northern Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan

Earth Systems and Environment (2026)

-

Spatiotemporal changes in heat stress exposure in India, 1981-2023

Nature Communications (2025)