Abstract

Porcine deltacoronavirus (PDCoV) is a newly emerging and special delta coronavirus, which infect mammals such as pigs, cattle and humans, as well as chickens and birds. Exploring RNA structures in the viral genome benefits the understanding of the role of RNA in the lifecycle of viruses. In this study, vRIC-seq is employed to analyze the RNA-RNA interaction in the whole genome structure of PDCoV in virions. About 12.87 and 13.52 million paired reads are obtained in two biological replicates, respectively, with 17.9% and 14.8% of them are identified as valid chimeric reads. These are employed to predict the RNA secondary structure, which is compact and highly structured. A twisted-cyclized conformation is observed in the RNA-RNA interaction map of PDCoV for the first time. 77 multi-way junctions are evenly distributed in the PDCoV genome. Our work provides fundamental structural insights that are essential for understanding the genomic structure and function, genetic evolution, and packaging characteristics of PDCoV.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Porcine delta coronavirus (PDCoV, δ-coronavirus) infects nursing piglets, causing watery diarrhea, vomiting, dehydration and high mortality, which result in significant economic losses to the global pig industry1. Importantly, PDCoV’s public health significance lies in its ability to cross species transmission, potentially infecting humans2, chickens3, cattle4, and other animals. The prevention and control of PDCoV impacts the development of animal husbandry and public health. However, there is a lack of effective antivirus drugs and candidate drug targets at present. Revealing the mechanism of PDCoV proliferation and analyzing the protein as well as nucleic acid structure will contribute to finding effective and novel antiviral targets.

As the genetic material, RNA nucleotide sequence not only encodes the essential information for protein synthesis, but also harbors structural information integral to its function. RNA structure can regulate process of virus proliferation, and it’s also an idea antivirus drug target5. For instance, the TAR element of HIV nascent 5’end viral RNA recruits the TAT protein to enhance transciption. Netilmicin, TAR-targeting molecules, presents an attractive antiviral activity6. Similarly, of 22 structure-similar motifs from dengue virus contribute to a compact global genome architecture, interacting with proteins, and regulating the viral replication cycle7. Frameshifting stimulation element (FSE) presented in the coding sequence (CDS) of coronavirus adopts pseudoknot or double stem-loop conformations, and regulates frameshifting efficiency as well as virus multiplication through conformational transformation, which is a potential antivirus drug target8,9,10. In addition, G-quadruplex secondary structure is formed from guanine-rich sequences in virus genome, which plays a crucial regulatory role in viral replication. G-quadruplex ligands have showed promise as antiviral agents11. Identifying the RNA structure in situ and the whole genome conformation will provide significant insights.

In recent years, methods for probing full-genome RNA structure have been rapid developed. Techniques such as SHAPE-seq.12, DMS-seq.13, SHAPE-Map14, and ic-SHAPE15 utilize chemical modification reagents like 1M7, DMS, NAI, and NAI-N3 to modify unpaired nucleic acids, respectively. And then, the modified information will transfer to the RT-stop or RT-mutation during the reverse transcription process. But these approaches have limitations in providing detailed RNA base-pairing information within double-stranded regions. Subsequently, PARIS16, COMRADES17, SPLASH18, RIC-seq.19 have been developed to reveal double-strand information and long-range interactions. These techniques use psoralen, psoralen-biotin, and formaldehyde, respectively, to cross-link RNA-RNA spatial interactions, which can be identified through chimeric reads generated by high-throughput sequencing. Currently, the genome structure of IAV20, ZIKV21,22, HIV-114, SINV23, VEEV23, and SARS-CoV-2 has been completely probed using various probing technologies24,25,26,27,28. SARS-CoV-2 has abundant genome structure information, which have brought our understanding of the pathogenesis and transmission mechanisms of virus to new heights, and facilitated the discovery of novel drugs based on it’s RNA structure information5.

In this study, vRIC-seq was used to elucidate the whole-genome structure of PDCoV. The sufficient chimeric reads were obtained by high-throughput sequencing after proximity-ligated spatial interacting RNA, which were pCp-biotin labeled. Valid chimeric reads of two biological replicates were highly reproducible on coverage and interaction strength. We constructed an interaction matrix and predicted secondary structure based on valid chimeric reads. The analysis of free energy and interaction strength confirmed the reliability of the structural information. These results showed that the whole-genome structure of PDCoV presented a twisted and cyclized conformation. About 61% (15,690 nt) nucleotides of the genome were base-paired. The proportion of base-paired nucleotides within the coding region for membrance protein reached 81.19%. There were 77 multi-way junctions that evenly distributed throughout the PDCoV genome.

Overall, our work represents the first comprehensive investigation into the whole-genome structure of the δ coronavirus PDCoV, which has the potential of interspecies transmission. The structure of PDCoV whole-genome was compact and highly structured. These data were greatly beneficial for understanding viruses and exploiting novel control strategies. We provided both raw and aligned data to facilitate custom reprocessing and further analysis.

Methods

Cell culture and virions sample preparation

Lilly Laboratories cell porcine kidney 1 (LLC-PK1, ATCC CL-101) cells were cultured in Minimun Essential Medium (MEM; Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin streptomycin (Invitrogen). Cells were cultured at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95–99% humidity.

LLC-PK1 cells were infected at MOI of 1.0 with PDCoV CHN-HN-2014 (GenBank accession: KT336560). Infections were performed in MEM supplemented with 7.5 μg/mL trypsinization. In the late stage of replication (10 hpi), infected cells were harvested by repeated freezing and thawing. Cell suspension removed cell fragments by 0.88 μm filter and centrifugation at 10,000 × g at 4°C. The virions were enriched by direct ultracentrifugation at 30,000 × g for 3 h at 4°C, and resuspended with ConA Binding buffer (20 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.9, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MnCl2, 0.01% Tween 20). The integrity of virions were visualized by transmission electron microscopy.

vRIC-seq library preparation

The library preparation was carried out in the same way as described in a previous study26. In brief, BioMag®Plus Concanavalin A beads (Polysciences, Inc. cat. 86057) were used to capture virions, and 500 μL purified virions were added to the 150 μL washed beads with ConA Binding buffer, and incubated for 10 min at room temperature. The beads were washed with ConA Binding buffer for three times and PBST buffer for once (1 × PBS, 0.1% Tween 20), and resuspended in 1 mL PBST buffer. The final concentration of 1% formaldehyde was used to fix the RNA-RNA interaction, and the glycine with final concentration 0.125 M was added to quench the formaldehyde.

The virions captured by beads were permeated by 1 mL of permeabilization buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 10 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 0.3% Triton X-100, 0.1% Tween 20, 1 × protease inhibitors (Sigma Aldrich), 2 U/ml SUPERase•In™ RNase inhibitor (Thermo Fisher Scientific)). After washing three times with 1 × PNK buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Tween 20), the virial RNA was fragmented by MN mixture (50 mM TrisHCl pH 8.0, 5 mM CaCl2, 0.03 U/μL micrococcal nuclease (Thermo Fisher Scientific)). After 10 min, the reaction was stopped by washing twice with 1 × PNK + EGTA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 20 mM EGTA, 0.1% Tween 20) and twice with 1 × PNK buffer.

The fragmented RNA was treated with FastAP alkaline phosphatase (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The reaction was stopped by washing with 1 × PNK + EGTA buffer twice, and 1 × high-salt wash buffer (5 × PBS, 0.1% Tween 20) twice, and three times in 1 × PNK buffer. The pCp-biotin was ligated to the 5’-end fragmented RNA by T4 RNA ligase (Thermo Fisher Scientific). After washing three times with 1 × PNK buffer, the RNA was treated with T4 polynucleotide kinase (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and the reaction was stopped by washing with 1 × PNK + EGTA buffer twice and 1 × PNK buffer twice. Subsequently, T4 RNA ligase was used proximity ligation in siut. After completing the proximity-ligated, the RNA was extracted by proteinase K, Trizol and chloroform according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

For strand-specific library construction, the RNA was fragmented used 5 × First-strand buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and incubated at 94°C for 5 min. Subsequently, the preblocked MyOne Streptavidin C1 beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific) by yeast tRNA was used to enrich pCp-biotin-marked RNA fragments according to the manufacturer’s instruction. To synthesize the first-strand cDNA, firstly, RNA was incubated at 65°C for 5 min, put it on the ice for 2 min immediately. Reverse transcription was performed by Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and incubated at 25 °C for 10 min, 42 °C for 40 min and then 70 °C for 15 min. Then, the dUTP second-strand cDNA was synthesized with Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I (Enzymatics) and the reaction mixture (10 μL of 5 × second-strand buffer (Thermo Fisher), 0.8 μL of 25 mM dNTPs with 80% of the dTTP replaced by dUTP, 20.5 μL of RNase-free water, 0.2 μl of 5 U/μL RNase H (Thermo Fisher)) and incubation at 16 °C for 2 h. The double-stranded (ds) DNA products were purified using 1.8 × AMPure beads (Beckman Coulter) following the manufacturer’s protocol. This was followed by conventional end-repair and purified again by 1.8 × AMPure beads. Of 2 pmol Illumina Y-shaped adaptors were ligated to the dsDNA using Quick T4 DNA Ligase (Enzymatics) after dA tailing, and purified twice with AMPure beads. An emulsion PCR followed as a second amplification step.

The adaptor-ligated cDNA was mixed with 1 μL of 10 μM Illumina PE1.0, 1 μL of 10 μM index primer, 1 μL of 50 mM MgSO4, 2.5 μL of 10 × Pfx buffer, 0.4 μL of 25 mM dNTPs, 0.4 μL of 2.5 U/μL Platinum Pfx DNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher) and 3 μL of USER enzyme (NEB). The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 15 min to allow the USER enzyme to digest the dUTP strand. Then at 94 °C for 2 min, the following PCR program run: 11 to 13 cycles of 94 °C for 15 s, 62 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 30 s. The 200–450 bp PCR products were purified from agarose gel by MinElute Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen). The DNA concentration was measured by Qubit (Thermo Fisher) and sequenced using Illumina HiSeq X Ten.

Data cleaning

The data cleaning process for vRIC-seq sequencing data included removing adapter sequences from reads, eliminating PCR duplicates, and filtering out low-complexity reads, which could be executed using fastp (v0.23.2)29. By default, fastp removed adapter sequences and set a criterion that allowed a read to have no more than 30% of its bases with quality scores below 20. This ensured the integrity and quality of the sequencing data. To eliminate PCR duplicates, we utilized the script provided by the developers of the vRIC-seq protocol19,26 (https://github.com/caochch/RICpipe/tree/master/step0.remove_PCR_duplicates/scripts). During each iteration, the script merged the sequences of read 1 and read 2 to form a complete read sequence. It then checked whether this combined sequence was already presented in the hash table. If the sequence was found in the table, the read pair was skipped. If not, the script wrote the sequence to the output file and added it to the hash table, marking it as encountered. This process ultimately yielded a cleaned FASTQ file.

Sequence alignment

Preparation of reference genomes was required before sequence alignment, including the PDCoV genome (ID: KT336560.1), the complete porcine genome (RefSeq: GCF000003025.6), as well as the ribosomal RNA sequences derived from the pig genome (18s rRNA, 5.8s rRNA, 12s rRNA, and 16s rRNA sequences). Next, a new directory was created to hold the reference genome indexes for STAR aligner (v2.7.1a)30. The–genomeDir parameter was specified to reference the previously constructed STAR index, which was essential for the accurate mapping of the sequencing reads to the corresponding reference genome. The main output files from STAR were ‘Unmapped.out.mate’, ‘Aligned.sortedByCoord.out.bam’, ‘Chimeric.out.junction’, and ‘Log.final.out’. These files represented the reads that unmapped, the reads that aligned directly, the reads that aligned in a chimeric fashion, and the alignment statistics, respectively. We used samtools (v1.9)31 to extract and calculate the number of aligned reads and coverage from the BAM file for different reference gene IDs.

To identify chimeric reads as effectively as possible, the following filtering steps were applied to the FASTQ files: Firstly, reads were removed if they were presented in both the star.chimeric.sam and star.align.sam files. Additionally, reads from star.align.sam had to satisfy the criteria that the FLAG value had to be less than 255, indicating a properly aligned read, and the difference between the read length and the aligned length should be fewer than 15 base pairs. Subsequently, the filtered FASTQ files were aligned to the viral genome using BWA (version 0.7.17)32, and chimeric reads were then extracted for the next analysis.

Identification and visualization of valid chimeric reads

The aligned reads and chimeric reads extracted from the sequence alignment were both employed to identify valid chimeric reads. These valid chimeric reads correspond to RNA fragments with proximate spatial locations and chimeric junction sites. The process was carried out in the following steps: Initially, paired reads from the sets of reads derived from both direct and chimeric alignments were selected based on their IDs. Subsequently, the length of the insertion fragments and the number of fusion sites were considered to categorize different types of paired reads and determine their classification as valid chimeric reads. Additionally, the unique discontinuous transcription of the coronavirus genome results in the production of numerous subgenomic RNAs (sgRNAs)33,34,35. The distinction between these sgRNAs and the insertion fragments was whether the fusion site contains a cytosine. If these sgRNAs were not removed, they could significantly bias the signal in the downstream interaction matrix. After several filtering steps, the interaction sites from the valid chimeric reads were ultimately extracted and used to generate a interaction matrix with the assistance of Juicerbox (v2.20.00)36.

To illustrate the algorithmic logic from paired reads to the interaction matrix, we would take an example involving two RNA fragments that were crosslinked together with a single fusion site:

-

1.

When the length of the inserted fragment was 150 nucleotides or shorter, it was assumed to be fully captured in the paired-end sequencing, with both ends of the fragment being read through. In such cases, chimeric reads that spanned the entire inserted fragment were deemed valid. Moreover, if the distance between the two ends of the fragment was sufficiently large (greater than 600 base pairs), the corresponding paired read 1 and read 2 were also preserved for further analysis. In this situation, a single inserted fragment might be recorded up to three times. To avoid redundancy, deduplication methods could be applied to remove these duplicate records.

-

2.

When the length of the inserted fragment was greater than 150 nt but less than 290 nt, the fragment was read through, and neither read 1 nor read 2 could individually cover the entire inserted fragment. If the paired reads partially overlap, concatenating read 1 and read 2 could achieve full coverage of the inserted fragment. In such case, the paired reads were consisted of one completely aligned read and one chimeric read. The chimeric read was recorded independently, and if the distance between the two ends of the inserted fragment was sufficiently long, the paired read 1 and read 2 would also be retained.

-

3.

When the length of the inserted fragment exceeds 290 bp, it was classified as a non-read-through segment. In such instances, the overlapping region between the paired reads was very short or entirely absent. If one of the reads included the chimeric site, it was similar to the second condition, where the chimeric read was recorded separately. If the distance between the two ends of the inserted fragment was adequately long, the paired reads were recorded once. If no reads spanned the chimeric site, the determination was made based exclusively on the positional relationships of the reads, and the paired reads that covered distant regions of the inserted fragment were the ones recorded.

-

4.

When there were multiple chimeric sites within a fragment, the results became more complex, but the algorithm logic remained the same. It still required a case-by-case analysis based on the length of the inserted fragment. Further elaboration on this matter was beyond the scope of this discussion.

After identifying the paired reads that represented the inserted fragments, the same process needed to be applied to analyze the RNA-seq data of PDCoV. RNA-seq data sets of PDCoV are available at NCBI database under Bioproject accession PRJNA690955. The chimeric sites of all sgRNAs were recorded, and the paired reads representing the sgRNAs of the coronavirus were removed. The remaining paired reads could be classified as valid chimeric reads, which would be used to construct an interaction matrix and facilitate data visualization.

Secondary structure prediction

To predict the RNA secondary structure of PDCoV genome, the initial step involved partition of the most suitable structural domains based on the information provided by the interaction matrix. This process entailed an iterative examination and refinement of the domain boundaries by calculating ratios as well as densities from the interaction matrix until no additional segmentation was necessary. The process was as follows: Initially, the full genome RNA was treated as a single structural domain, and a suitable site needed to be identified to split this domain into two distinct subdomains. To identify the optimal division point, various sites were systematically evaluated, and the interaction frequency along with the interaction score (connection score) for the two resulting structural domains were computed. The domains were grouped together if the interaction score exceed 0.03, provided that the two ends were adjacent or overlapping. Ultimately, several optimal sites for domain division were identified across the full genome. It was important to note that to maintain long-distance interactions, domains shorter than a specified threshold length will not be subdivided any further.The formula for the connection score was as follows:

Subsequently, within each structural domain, the most characteristic interaction sites were identified and selected. Following clustering, the base sequences that adhered to rules of complementary base pairing were selected as rigid constraints. These constraints were subsequently fed into RNAstructure (version v6.3)37 for secondary structure prediction. In the final step, the predicted secondary structure from all the individual structural domains were integrated to yield the secondary structure of the PDCoV whole genome. The complete vRIC-seq sequencing data analysis process was showed in Fig. 1.

Data Records

Technical Validation

Display of quality control results

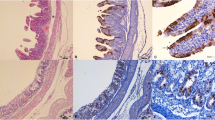

For sample preparation, the purified virion was visualized by transmission electron microscope, which allowed the observation of intact enveloped virions with a distinct coronal structure (Fig. 2a). The cDNA libraries were constructed from two separate biological replicates according to vRIC-seq protocol. The libraries were sequenced on Illumina platform, generating 89.842602 and 91.708408 million reads per sample. Following the data cleaning process outlined above, the number of unique reads was reduced to around 25.73 and 27.03 million per sample. The deduplication rate was approximately 71% (Fig. 2b). Subsequently, STAR was used to analyze the distribution of cleaned reads across the viral genome and the host genome (Fig. 2b), showing that approximately 95% of the reads from all samples were mapped to the viral genome. A small number of reads were mapped to host genome. Approximately 0.05% of the reads corresponded to virus-to-host RNA interactions (Fig. 2c). This could be attributed to the contamination of the host genome during virus purification. However, it did not preclude another intriguing possibility that a minor fraction of the host genome might be present within the virion.

Virus samples and vRIC-seq sequencing data display (a). Electron microscopic images of purified PDCoV particles.(b). The processing of raw data. The green and pink bar charts represented the number of reads in the raw and cleaned FASTQ files, respectively. (c). Distribution of data. Two sets of biological replicates with different colors in the pie and bar charts displayed the proportion of sequencing data aligned to the virus genome, host genome, virus-to-host genome and unmapped reads.

Identification of the valid chimeric reads and construction of interaction matrix

The reads mapped on viral genome were combined to form paired reads, resulting in approximately 12.87 and 13.52 million paired reads for each sample, respectively. Of 2.31 and 2.00 million valid chimeric reads were identified from paired reads in each sample, accounting for 17.96% and 14.81%, respectively (Fig. 3a). To verify whether the valid chimeric reads were captured by pCp-biotin labeling, the proportion of cytosine at the chimeric junction sites was calculated, which was approximately 86.6% (Fig. 3b). The coverage of valid chimeric reads and interaction matrices generated from the two biological replicates were largely consistent with each other. The above results demonstrate the reliability of the experimental results and high sample reproducibility. It was worth noting that the PDCoV interaction matrix exhibits prominent long-range interactions, resembling the wings of a dragonfly (Fig. 3c).

Identification of the valid chimeric reads and construction of interaction matrix. (a). The proportion of valid chimeric pairs in all paired reads. The green and pink represented valid chimeric pairs and discard pairs, repectively. Two bar charts represented two sets of biological replicates (b). The percentages of cytosine at the junction of chimeric reads. The horizontal axis used the junction site of all valid chimeric reads as the origin, and statistics were compiled on the percentage of cytosines within the 20 bases before and after the junction site. Two colors represented two sets of biological replicates (c). The coverage of chimeric reads and interaction matrix of two biological replicates. In the heatmap, the shade of color represented the strength of viral RNA interactions.

Analysis of interaction matrix

The scattered plot demonstrated a high degree of correlation (R = 0.9794) in the coverage of PDCoV genomic valid chimeric reads between the two biological replicates (Rep 1 and Rep 2) (Fig. 4a). Additionally, the majority of the nucleotides coverage had an effective read depth ranging from 1,000x to 4,000x (Fig. 4b). The correlation in the interaction strength of the PDCoV genomic matrix was remarkably high between the two biological replicates (R = 0.973) (Fig. 4c). The distance decay curve served as a crucial indicator of the quality of the original low-resolution structural data. It was worth noting that there was a very long distance and high frequency genome interaction in the distance decay curve, suggesting that the viral genome was in a cyclized and distorted state within the virion (Fig. 4d).

The reliability and feature analysis of the PDCoV genome interactions. (a). Scatter plot showed the correlation for coverage of chimeric reads along the PDCoV genome in two biological replicates (Rep1 and Rep 2). R, Pearson correlation coefficient (b). The coverage of chimeric reads for each nucleotide of the PDCoV genome.The vertical axis represented the number of bases, while the horizontal axis corresponded to the coverage of each base (c). Scatter plots showed the correlation between two biological replicates for the number of chimeric reads (interaction strength). R, Pearson correlation coefficient (d). Distance decay curve of two biological replicates.The horizontal axis represented the distance between interacting RNAs, while the vertical axis represented the number of chimeric reads corresponding to different distances.

Prediction and analysis of secondary structure

This study presented the secondary structure of the complete genome of PDCoV (Fig. 5). We identified 30 clustered interactions that indicate the presence of long-range interactions within the PDCoV genome (Table 1). We also presented different topological domains ranging from 600 to 1,200 nucleotides (Fig. 6a). To validate the reliability of our predicted secondary structure, the final predicted stem-loop structures demonstrated lower free energy compared to the stem-loop structures predicted from randomly shuffled sequences (Fig. 6b). Additionally, our predicted secondary structure matched well with the vRIC-seq sequencing data, as base-paired regions showed stronger interaction strength than size-matched unpaired control sequences (Fig. 6c). Figure 6d showed that among the secondary structures predicted by two biological replicates, the paired stem-loop structures were basically the same, with common duplexes of up to 7,686.

The reliability and feature analysis of the PDCoV genome secondary structure. (a). Distribution of topological domains with differerent lengths. The horizontal axis represented the length of the pseudo structural domain, and the vertical axis represented the number of structural domains with different lengths (b). The minimum free energy of duplexes (n = 30) detected by vRIC-seq were compared with the shuffled control (c). Pairwise interacting RNA fragments (n = 7844) showed more vRIC-seq signals than the random controls that had the same spanning distance (n = 7844) (d). The Venn diagram showed the overlap of double-stranded regions between the two sets of biological replicates. Two colors represented two sets of biological replicates (e). Base-paired RNA content of individual regions (f). Summary of the number of multi-way junctions and the corresponding stems in our secondary structure model.

In our structural model, the median and mean distance between two paired regions in PDCoV was 27 and 50 nt, respectively. The maximal spanning distance (763 nt) was observed for a duplex formed between two fragments: 24,074-24,079 nt and 24,831-24,836 nt, which located in nucleocapsid (N) coding region and completely covered coding sequences of NS7 and NS7a. We found that about 61% (15,690 nt) of the PDCoV genome were base-paired. The proportion of base-paired nucleotides of membrance protein (M) coding region reached 81.19% (Fig. 6e). And our model precisely recapitulated the stem-loop structures in the 5’UTR (SL1-SL7), as well as 3’UTR structures including the s2m and the HVR. Besides identifying many duplexes, our structural model revealed 77 multi-way junctions, including 29 three-way junctions, two 11-way junctions, two 12-way junctions, one 13-junway junction and one 14-way junction (Fig. 6f). It seems that these junctions evenly distributed in the PDCoV genome, and illustrated that there were a lot of long-distance interactions.

Code availability

No specific code or script was used in this work. The data analyses used standard bioinformatic tools specified in the methods.

References

Sun, J. et al. Epidemiology of porcine deltacoronavirus among Chinese pig populations in China: systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Vet Sci. 10, 1198593 (2023).

Lednicky, J. A. et al. Independent infections of porcine deltacoronavirus among Haitian children. Nature. 600, 133–137 (2021).

Liang, Q. et al. Susceptibility of Chickens to Porcine Deltacoronavirus Infection. Viruses 11, 573 (2019).

Jung, K., Hu, H. & Saif, L. J. Calves are susceptible to infection with the newly emerged porcine deltacoronavirus, but not with the swine enteric alphacoronavirus, porcine epidemic diarrhea virus. Arch Virol. 16, 2357–2362 (2017).

Szczesniak, I. et al. Structural and Functional RNA Motifs of SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza A Virus as a Target of Viral Inhibitors. Int J Mol Sci. 24, 1232 (2023).

Stelzer, A. C. et al. Discovery of selective bioactive small molecules by targeting an RNA dynamic ensemble. Nat Chem Biol. 7, 553–9 (2011).

Boerneke, M. A. et al. Structure-first identification of RNA elements that regulate dengue virus genome architecture and replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 120, e2217053120 (2023).

Zimmer, M. M. et al. The short isoform of the host antiviral protein ZAP acts as an inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 programmed ribosomal frameshifting. Nat Commun. 12, 7193 (2021).

Hill, C. H. et al. Structural and molecular basis for Cardiovirus 2A protein as a viral gene expression switch. Nat Commun. 12, 7166 (2021).

Sun, Y. et al. Restriction of SARS-CoV-2 replication by targeting programmed -1 ribosomal frameshifting. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 118, e2023051118 (2021).

Ruggiero, E. & Richter, S. N. G-quadruplexes and G-quadruplex ligands: targets and tools in antiviral therapy. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 3270–3283 (2018).

Lucks, J. B. et al. Multiplexed RNA structure characterization with selective 2’-hydroxyl acylation analyzed by primer extension sequencing (SHAPE-Seq). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108, 11063–8 (2011).

Rouskin, S. et al. Genome-wide probing of RNA structure reveals active unfolding of mRNA structures in vivo. Nature. 505, 701–705 (2014).

Siegfried, N. A. et al. RNA motif discovery by SHAPE and mutational profiling (SHAPE-MaP). Nat Methods. 11, 959–965 (2014).

Luo, Q. J. et al. RNA structure probing reveals the structural basis of Dicer binding and cleavage. Nat Commun. 12, 3397 (2021).

Lu, Z. et al. RNA Duplex Map in Living Cells Reveals Higher-Order Transcriptome Structure. Cell. 165, 1267–1279 (2016).

Ziv, O. et al. COMRADES determines in vivo RNA structures and interactions. Nat Methods. 15, 785–788 (2018).

Aw, J. G. et al. In Vivo Mapping of Eukaryotic RNA Interactomes Reveals Principles of Higher-Order Organization and Regulation. Mol Cell. 62, 603–617 (2016).

Cai, Z. et al. RIC-seq for global in situ profiling of RNA-RNA spatial interactions. Nature 582, 432–437 (2020).

Dadonaite, B. et al. The structure of the influenza A virus genome. Nat Microbiol. 4, 1781–1789 (2019).

Huber, R. G. et al. Structure mapping of dengue and Zika viruses reveals functional long-range interactions. Nat Commun. 10, 1408 (2019).

Li, P. et al. Integrative Analysis of Zika Virus Genome RNA Structure Reveals Critical Determinants of Viral Infectivity. Cell Host Microbe. 24, 875–886.e5 (2018).

Kutchko, K. M. et al. Structural divergence creates new functional features in alphavirus genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 3657–3670 (2018).

Huston, N. C. et al. Comprehensive in vivo secondary structure of the SARS-CoV-2 genome reveals novel regulatory motifs and mechanisms. Mol Cell. 81, 584–598.e5 (2021).

Sun, L. et al. In vivo structural characterization of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA genome identifies host proteins vulnerable to repurposed drugs. Cell. 184, 1865–1883.e20 (2021).

Cao, C. et al. The architecture of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA genome inside virion. Nat Commun. 12, 3917 (2021).

Ziv, O. et al. The Short- and Long-Range RNA-RNA Interactome of SARS-CoV-2. Mol Cell. 80, 1067–1077.e5 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. In vivo structure and dynamics of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA genome. Nat Commun. 12, 5695 (2021).

Chen, S. et al. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics. 34, i884–i890 (2018).

Dobin, A. et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 29, 15–21 (2013).

Danecek, P. et al. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. Gigascience. 10, giab008 (2021).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 26, 589–595 (2010).

Athmer, J. et al. Selective Packaging in Murine Coronavirus Promotes Virulence by Limiting Type I Interferon Responses. mBio. 9, e00272–18 (2018).

Wang, D. et al. The SARS-CoV-2 subgenome landscape and its novel regulatory features. Mol Cell. 81, 2135–2147.e5 (2021).

Sola, I. et al. Continuous and Discontinuous RNA Synthesis in Coronaviruses. Annu Rev Virol. 2, 265–288 (2015).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicebox Provides a Visualization System for Hi-C Contact Maps with Unlimited Zoom. Cell Syst. 3, 99–101 (2016).

Bellaousov, S. et al. RNAstructure: Web servers for RNA secondary structure prediction and analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 41(Web Server issue), W471–474 (2013).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP487930 (2024).

Sun, J. GEO https://identifiers.org/geo/GSE254992 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Programs of China (No. 2021YFD1801102), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22077043, 32473010), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2662023PY005 to DW), HZAU-AGIS Cooperation Fund (SZYJY2022016 to DW), Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province (2021CFA061 to DW), and the Funding from National Key Laboratory of Agricultural Microbiology(AML2023B05 to DW). We appreciate Professor Yuanchao Xue of Institute of Biophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences for providing the guidance of this study. We thank Professor Shaobo Xiao of College of Veterinary Medicine, Huazhong agricultural university for providing the virus and cell. We thank Professor Li Li of College of Informatics, Huazhong agricultural university for providing guidance of data analysis related work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.G.W. and Z.W. conceived of the project. J.S. collected the samples, library preparation and wrote the manuscript. Z.Y.H. performed the data analysis and wrote the manuscript. L.C. and Y.X.D. performed data analysis and revised the manuscript. L.R.G. processed the data into the figure and collected the samples. Y.X.W. contributed to library preparation. G.Y.L. assisted in the preparation of samples. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, J., Huang, Z., Chen, L. et al. RNA architecture of porcine deltacoronavirus genome inside virions detected by vRIC-seq. Sci Data 11, 1124 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03975-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03975-w