Abstract

The Loess Plateau is a region of importance in geomorphologic research because of its typical loess layers and intense surface erosion. Analysing the landforms on the Loess Plateau is helpful for understanding changes in the surface environment. However, geomorphologic data with high resolution are lacking for the Loess Plateau, which limits the progress of geomorphologic studies at finer scales. This study provides the first 30 m resolution landform classification and characteristics dataset for the Loess Plateau (LPL30). Considering morphological characteristics, dominant dynamics, and material conditions, the landforms on the Loess Plateau were categorized into three levels with 28 landform types. Moreover, we calculated 6 metrics to quantify the spatial distribution and category composition of the landforms in 16 analytical units with different scales and shapes, resulting in 96 geomorphologic descriptors. This dataset provides fundamental data for the study of landform formation processes and evolution mechanisms at various scales and can be employed as a geomorphological gradient to support ecology and environmental research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

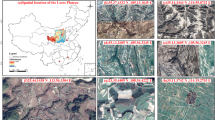

The Loess Plateau is one of the most significant areas of geomorphologic research because of its unique material conditions and geographic environments1,2. As shown in Fig. 1, this plateau is in the middle reaches of the Yellow River in Central China and is close to several deserts (e.g., Tengger Desert, Ulan Bur Desert and Kubuqi Desert) and the Tibetan Plateau. The thick loess from neighbouring deserts and and other potential sources covers the tertiary and other old rock strata3, hence the name “Loess Plateau”1. The monsoonal rainfall is responsible for the emergence of several rivers in the region, including several large tributary rivers (such as the Weihe River, and Fenhe River) of the Yellow River, which have high water and sand contents. The Earth’s internal and external forces significantly influence the surface evolution and shape of various landforms in this area4,5,6. Widespread erosional gullies and other erosional landforms have formed on the Loess Plateau, especially under the influence of water erosion7,8,9. The study of landform morphology and distribution patterns can improve the understanding of the external force distribution and facilitate the discovery of the interaction mechanisms between surface morphology and driving factors10,11. Moreover, intense soil erosion on the Loess Plateau poses great challenges to the ecological environment and sustainable development in this area12,13. The discussion of landform morphological characteristics and distribution patterns can assist in analysing the risks of soil erosion in different regions and contribute to the effective allocation of social resources to reduce occurrences and mitigate the impact of disasters13,14. Moreover, these endeavours play crucial roles in protecting the ecological integrity of the Loess Plateau15,16,17. Understanding the distribution patterns of different landform types facilitates the identification of critical areas that require ecological restoration and conservation. Furthermore, the landform-related knowledge derived from these works can aid in optimizing land use planning and agricultural practices, contributing to establishing a more harmonious relationship between human activity and the environment18.

Geomorphologic data are among the most important data types for studying the landform distribution and geomorphologic process of the Loess Plateau. In this region, the most typical geomorphologic data are loess-related data, such as loess distribution3, loess thickness19, and loess sources2. After diverse geomorphologic information is integrated, we can obtain landform type data, which are fundamental to environmental and geomorphological studies on the Loess Plateau. At the macroscale, Zhou, et al.20 and Li, et al.21 classified surfaces into binary structures to depict the basic surface patterns of the Loess Plateau. In particular, there is valuable research on classifying loess landforms and producing corresponding datasets on the Loess Plateau. Liu, et al.7 discussed loess erosion gullies in key soil and water loss areas. Liu, et al.22 and Yuan, et al.23 studied loess tablelands and provided public datasets. Li, et al.8 extracted and analysed loess ridges and loess hills. In addition, some regional- or global-scale landform classification studies have produced geomorphologic data, which cover the Loess Plateau region24,25,26,27. Other studies have been conducted in related fields, such as ecology, to produce landform classification datasets28.

The advancement of global observation systems has facilitated the production of high-quality and fine-scale fundamental data. Moreover, researchers are emphasizing the production of finer geomorphologic data29, particularly for landform type data. digital elevation models (DEMs), which provide abundant morphological information, have become crucial data sources in these studies29,30. Methods based on derivative combinations calculated from DEMs constitute the most common and fundamental framework in landform classification31. Although public DEMs with resolutions of approximately 30 m are now available, there is still a lack of landform classification data at the corresponding scale. Balancing gradual and abrupt changes in landform characteristics remains challenging when processing high-resolution DEMs21,29. Abrupt geomorphologic characteristics are the most direct evidence of changes in landform types. However, owing to the complexity of the environmental factors and dynamic processes involved in the formation of landforms, the junction of different landform types typically results in gradual changes in geomorphological characteristics. In the Loess Plateau region, the complicated interaction of loess deposits and surface erosional processes has given rise to zones characterized by gradual transitions, which increase the complexity of determining class boundaries. For example, typical erosional gullies often include obvious boundary lines where the slope undergoes significant changes32, whereas many gullies exist in the Loess Plateau without these abrupt slope changes. It is difficult to express the characteristics of gradual transitions via common derivatives used in landform classification, leading to difficulties in accurate classification8. It is necessary to evaluate whether the adopted quantitative derivatives and features can depict the inherent characteristics of the landform, which is beneficial for addressing the complexities due to abrupt changes and gradual variations. For example, studies that are primarily grounded in local topographic derivative analyses usually fail to adequately consider the gradually changing attributes and contiguous nature of landforms, consequently damaging the coherence and completeness of landform classification outcomes. It is necessary to integrate geomorphological knowledge to either redesign or select appropriate quantitative factors.

In this study, we completed a multilevel landform classification of the Loess Plateau on the basis of DEMs and quantified the characteristics of the spatial distribution of the landforms. The classification objects in this study included both landform types that reflect fundamental morphological characteristics and categories designed for the unique formation mechanisms of the Loess Plateau. We considered the morphological characteristics, dominant forces, and material basis of the landforms and produced 28 categories of landforms. Furthermore, on the basis of the classification results, the spatial distributions and category compositions of the landform types were quantified from an object-based perspective, and 96 descriptors were generated. These descriptors were calculated on the basis of 16 analysis units and can support geomorphologic and environmental science research at multiple scales. Through this work, we developed the most refined and comprehensive landform classification and derivative dataset for the Loess Plateau (LPL30). This dataset provides fine-scale landform blocks with abundant textures. The resolution of the LPL30 data is similar to that of the current mainstream remote sensing data, which makes the joint use of the data relatively simple. The detailed information on landform types, boundaries and textures provided by LPL30 can help geomorphologists carry out more in-depth surface analysis, including exploring landform patterns and simulating landform evolution.

Materials and Methods

Study area and source data

The Loess Plateau is an important geographical region located in the middle and upper reaches of the Yellow River (Fig. 1). It spans from approximately 104°40′E to 111°15′E in longitude and 32°05′N to 39°35′N in latitude, covering an area of approximately 600,000 square kilometres. From a geological perspective, the Loess Plateau region is composed of three blocks: the Ordos stable block, the Longxi block, and the Fenwei neotectonic rift. The Loess Plateau has a semiarid and arid climate, and the precipitation in this area is primarily concentrated in the summer. The Loess Plateau is the largest loess region in the world, and the primary sources of loess include the Qilian Mountains on the northeastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau and the Gobi-Altai33,34 and Hangayn Mountains in southern Mongolia34. Under intense surface erosion, this area is characterized by unique loess landforms, such as loess gullies, loess hills and loess tablelands.

In this study, the Forest And Buildings removed Copernicus DEM (FABDEM) (https://data.bris.ac.uk/data/dataset/25wfy0f9ukoge2gs7a5mqpq2j7)35 was selected as the primary source data to support landform classification. This dataset employs a machine learning algorithm to remove buildings and forests from the Copernicus digital elevation model. This dataset is now one of the most popular DEMs used in geomorphologic and other related studies and can represent bare land well. This approach can help us quantify ‘real’ landform characteristics while eliminating the influence of land cover.

Landform classification

Landform classification is the basis for geomorphological research. The identification of classification systems and objects is the initial and crucial step in landform classification endeavours. During the process of defining classification objects, they should align with the foundational principles and rules of geomorphology and ensure the reasonability of the chosen objects. Furthermore, it is essential to consider the differences in the definitions of landform types across various disciplines. This consideration ensures that the produced classified data possess a relatively high degree of utility and are capable of supporting research not only within geomorphology but also in related disciplines, such as ecology and geology.

A landform is a mixture of forces, processes and material bases in a specific period and can be summarized as a process‒force association36. In landform classification, it is necessary to consider both the external presentation and the factors influencing landform formation. Therefore, in this study, we constructed a multilevel classification system to support landform research on the Loess Plateau. We considered morphological characteristics (MCs), dominant forces (DFs) and surface materials (SMs) to perform landform classification on the Loess Plateau. We define a comprehensive system of landform objects shown in Supplementary Tables 1–3. The following content is specific to each level. We develop a feasible classification framework (Fig. 2) for a diverse range of objects.

-

(1)

MC level: The comprehensive effects arising from various factors, such as earth dynamics and material composition, are ultimately reflected in surface morphology37. Currently, landform classification on the basis of morphological characteristics is the most commonly used analytical approach in related studies24,26,37. Landform morphology directly influences physical processes on the Earth’s surface. For example, surface morphology affects surface hydrological processes and influences the direction and intensity of water erosion38,39. Moreover, landform morphology is closely related to human activity and life. Altitude and associated differences in the physical environment directly impact human activity areas40. Therefore, in this study, we selected morphological characteristics for the first analysis to categorize surfaces into basic landform types (Supplementary Table S1).

-

(2)

DF Level: Earth forces are the driving factors behind landform formation. Under the influence of different forces, surface materials undergo various morphological or compositional changes, resulting in diverse landform types41. On the Loess Plateau, water and wind erosion forces led to the formation of numerous gullies and intergully areas, forming a binary landform structure20,21. Analysing gullies and intergully areas will further improve our understanding of the intensity and spatial patterns of the dominant driving forces acting on the Loess Plateau. Therefore, in this study, we incorporated these forces and classified the surface into gully and intergully landforms (Supplementary Table S2), which served as the basis for further subdivision of landform types on the basis of their morphological characteristics.

-

(3)

SM Level: In the region covered with different materials on the Loess Plateau, very different landform types have developed. Loess deposits are abundant in the central region of the Loess Plateau and provide the fundamental conditions for the formation of loess landforms1. A loess landform is a type of landform formed under the joint action of a particular material foundation and constructive forces1,42. In terms of material foundation, loess landforms formed on loess deposits that accumulated during the Quaternary period. Wind leads to the transport of loess material from deserts, as shown in Fig. 1, to the Loess Plateau, which results in the development of extensive loess layers in the region, with the thickness gradually decreasing from west to east. Moreover, the combined effects of various forces, including water erosion, wind erosion, underground erosion, and gravity erosion, have contributed to the formation of a diverse range of loess landform types (such as loess tablelands, loess ridges, loess hills and loess gullies) in this area. Additionally, this region contains mountainous and hilly areas dominated by bedrock formations, which increase the landform diversity on the Loess Plateau. Therefore, we used material data to perform SM-level classification to provide new insights for landform research.

Workflow of the multilevel landform classification process. MC level: workflow of landform classification on the basis of morphological characteristics. DF level: workflow of landform classification considering dominant forces. SM level: workflow of landform classification incorporating surface material.

MC level: landform classification on the basis of morphological characteristics

Properly measuring terrain relief is an important foundation for conducting landform classification on the basis of morphological characteristics. The terrain relief index (TRI) is a commonly used derivative for quantifying terrain relief in geomorphological studies43. However, traditional methods for calculating the TRI often use a fixed window size, such as a 3 × 3 pixel window, to compute the difference between the maximum and minimum elevations within the window. Determining the optimal window size for this process can be highly complex, and the optimal window size may vary significantly in different landform regions. Therefore, to increase the accuracy of the proposed method in representing terrain relief, we designed a new method for calculating the TRI. With this new method, we did not set a fixed window in the calculation of terrain relief. Rather, we employed a method similar to the height above nearest drainage (HAND) principle44, which emphasizes the elevation difference between a surface location and its nearest drainage node. Instead of directly measuring from the nodes, we constructed a simulated terrain base using these drainage networks before calculating elevation differences. The new method consists of the following steps: (1) Extraction of the drainage network via digital hydrological analysis, which serves as a control for the base terrain of the study region. A flow accumulation threshold of 40,000 is adopted to extract the major drainage network effectively and avoid potential fake networks. (2) An irregular triangulated network is constructed on the basis of the control lines and converted into a DEM (terrain base) that covers the entire region. In this step, initially, positions along the drainage network were converted into points, and their corresponding elevations were recorded in the attribute table of these points. These points were subsequently transformed into a terrain base via the creation of a triangulated irregular network (TIN). (3) Subtraction of the DEM data from the simulated terrain constructed in the previous step, with the difference serving as the new TRI. Figure 2 shows the steps used in landform classification on the basis of morphological characteristics. First, based on the DEM data, we extracted topographic information, including elevation, slope, and terrain relief. Elevation values can be directly obtained from the DEM, and slopes can be calculated by differencing the DEM. The TRI can be obtained through the abovementioned steps. Second, we used the slope and the TRI to extract plains. Tablelands were grouped into the plains category through this step. Tablelands are generally taller than the surrounding areas are, resulting in topographical undulations at their boundaries. To separate tablelands from plains, we converted the plain raster data into vector objects and assigned unique identifiers to each individual block. We subsequently calculated the average TRI for each individual block. Referring to prior rules for tableland classification27, we established a criterion where blocks with an average TRI of less than 30 metres were categorized as plains, whereas those with an average TRI greater than 30 metres were classified as tablelands. This criterion effectively segregates plateaus from plains, enhancing the precision of our geomorphic classification. Third, we classified hills and mountains according to the landform classification criteria provided in27, which employs terrain relief descriptors as a reference for separating hills and mountains. In this study, we calculated the new TRI to replace the traditional index of terrain relief. Afterwards, we could obtain plains, tablelands, hills and mountains. These four landforms are regarded as MC_L1 landforms on the basis of their morphological characteristics. Finally, the MC_L1 types are separated into additional MC_L2 landforms according to the elevation difference.

DF level: landform classification considering dominant forces

Typically, there is a relatively distinct boundary line (referred to as the “shoulder line”) between gullies and intergully areas45,46. However, owing to the complexity of landform formation processes, the boundary lines between gullies and intergully areas are usually ambiguous. In other words, regions with clearly defined boundary lines are relatively rare. Traditional gully extraction methods face great challenges in terms of their applicability and generalizability over large areas47. In this study, we introduced a classification method for gullies and intergully landforms. Gullies include more drastic terrain variations, making it challenging to find suitable classification criteria, whereas intergully areas are relatively homogeneous and thus suitable as initial classification objects. Therefore, this method starts by extracting intergully landforms while considering the remaining areas to be gullies. To extract the intergully landforms, we followed these steps. (1) Extract local high points: Local high points are a subset of intergully areas, representing the uppermost regions of the intergullies. (2) These local high points are treated as seed points, and an accumulation algorithm is utilized to calculate the accumulated slope (AS)21,48. The AS is a derivative that represents the long-distance relationship of the slope gradient between two different locations. This process is similar to cost distance analysis in the GIS (Geographic Information System), which calculates the shortest path from each location to a target point and outputs the minimum cost for each location. This approach effectively balances local and global characteristics, ensuring the integrity of landform objects while making efficient use of terrain relief. (3) An automated adaptive threshold approach is implemented to classify erosion gullies and intergully areas on the basis of the calculated slope accumulations. Thus, we completed the first-level classification of landforms while considering dominant forces.

We subsequently performed derivative calculations for gullies and intergully landforms to classify the second-level landforms. For the intergully areas, we used slope as the classification criterion, dividing the intergully areas into flat, gentle, and steep intergully landforms. For gullies, two metrics were used: the gully incision depth (GID) and the gully dissection degree (GDD). These two metrics are calculated at the small watershed scale and provide an analysis of gullies from vertical and horizontal perspectives. These two derivatives can effectively reflect the development of gullies. The GDD was obtained by calculating the proportion of gully area to total watershed area. We designed two steps to obtain the GID. (1) The watershed boundary was extracted, and the elevation on the watershed boundary was used to construct an irregular triangular network, which was subsequently converted into topographic data (reconstructed DEM). (2) The gully incision depth was calculated by subtracting the real DEM from the reconstructed DEM. The difference represents the gully incision depth. On the basis of the abovementioned three derivatives, we were able to further classify gully and intergully landforms.

SM level: landform classification incorporating surface material

By comprehensively reviewing previous research in this area, we identified the classification objects, as shown in Supplementary Table 3. According to previous research, loess gullies and loess tablelands, which have distinctive morphologies, are relatively easy to be distinguished from their surrounding areas22,49. However, there is still a lack of specific classification methods for loess ridges and hills. Differentiating between loess ridges and loess hills has always been a challenge in related research. In terms of morphological characteristics, loess ridges are typically elongated with relatively flat tops, whereas loess hillocks are generally circular or nearly circular with smoother shapes. However, owing to the developmental process from loess ridges to loess hills, many landform objects exhibit morphological characteristics that resemble both loess ridges and loess hills. In other words, the gradual transition of landform characteristics during development complicates traditional classification methods based on visual interpretation or basic topographic derivatives, increasing the difficulty of classifying loess ridges and hills. The primary zone of soil and water loss is considered the core region of this plateau. This area has abundant loess deposits as well as exposed bedrock formations, making it a focal point for landform studies. This section describes the primary zone of soil and water loss on the Loess Plateau.

In this study, we introduce a loess landform classification method that is guided by geomorphological knowledge. This method is specifically applied in areas covered by loess. Regions covered with bedrock are classified into bedrock mountains and bedrock hills via a methodology similar to that described in Sect. 3.1. Among the loess landforms, loess tablelands present distinct features characterized by elevated and flat terrain. We applied a method similar to that used for tableland classification to extract loess plateaus. We propose a classification method for loess ridges and loess hills on the basis of a combination of landform features.

Step 1: Loess ridges and loess hills have uneven terrains, and in our definitions, they fall under the category of intergully landforms. Therefore, we utilized the integrated results in Sect. 3.2 as potential regions.

Step 2: Loess hills typically have more pronounced peaks than loess ridges do. In general, in the Loess Plateau region, loess hills usually contain local high points. In real topography, due to the influence of local abrupt changes, it is often challenging to extract local high points accurately. Therefore, we designed an extraction method based on inverse topography. This process includes the following steps:

-

(1)

Obtain the inverse terrain. The inverse terrain data are obtained by reversing the real topography. The DEM can be subtracted from the maximum values of the DEM. In inverse terrains, elevated areas (e.g., loess ridges and loess hills) become depressions.

-

(2)

Extract depressions in inverse terrains (e.g., elevated areas in real terrain) via hydrological analysis methods commonly used in digital terrain analysis. However, the results obtained via depression extraction cannot separate loess hills on large loess ridges because during the depression filling process, the long ridge area is considered an entire depression, resulting in this area being classified as a loess hill. This process led to the appearance of numerous pseudoless hills in the results.

Step 3: To separate loess ridges from loess hills in the results obtained in Step 2, we design a classification method based on terrain feature combinations. Studies of loess ridges and loess hills reveal that their most significant difference lies in their morphological characteristics. Within the extent of loess ridges, there is usually only one peak with no significant valley or the absence of a clear peak or valley. Loess hills have either a single peak or multiple continuous peaks, with valleys between them. Therefore, by analysing the peaks and valleys within each landform unit and their relationships, as shown in Fig. 3, we can optimize the results for loess ridges and hills.

Quantification of landform patterns

Determination of analysis units

In the process of quantifying the landform distribution, the size and shape of the analysis units can introduce uncertainties into the calculation results and the presentation of distribution patterns. To comprehensively reflect the spatial patterns of landforms, we selected three types of unit shapes (e.g., regular grids, watershed units, and mountain units). Regular grid units are the most fundamental units in spatial pattern studies and have been widely used in research related to climate, precipitation, and other fields50,51. Watersheds are natural units with strong internal homogeneity in terms of material and energy, making them a theoretically sound choice for studying regional variations in landforms. These methods have been effectively used in studies involving geomorphic inheritance52 and erosion gully analysis7. Mountain units have attracted increased attention in geomorphological research in recent years29; they can be considered “watershed units” on reversed topography (e.g., obtained by reversing normal topography) and correspond to isolated mountains or parts of mountains on real topography. Mountain units also exhibit strong homogeneity in terms of energy, materials, and other geographical elements. Watershed units and mountain units can be viewed as complementary analysis units, and joint analysis of these two units can better reveal the spatial differences in landform characteristics. Furthermore, landform patterns may vary at different analysis scales. Therefore, we applied four different size constraints to each type of unit to study the spatial patterns at different scales. For regular grid analysis, we used grid unit boundary lengths of 5, 10, 50, and 100 kilometres. For watershed analysis, we employed area thresholds of 5, 10, 100, and 500 square kilometres, resulting in 65702, 34385, 4308, and 619 watershed units, respectively. In the mountain unit analysis, we used the same four area thresholds as the watershed units, resulting in 45454, 23015, 2426, and 219 mountain units.

Descriptor selection and calculation

A set of descriptors related to landform spatial patterns are derived in this subsection. We quantified the spatial distribution of landforms from two perspectives: aggregation and diversity. These two categories of descriptors play crucial roles in landscape assessment and support the quantitative representation of surface patch distribution characteristics. Analysing the spatial distribution patterns of landforms from a landscape perspective can enhance the collaborative use of our provided landform data with related disciplines, such as ecology and landscape studies. Table 1 displays the selected descriptors, the calculation methods, and their meanings.

Descriptions of the quantified landform characteristics of the Loess Plateau. The explanations of COHESION, DIVISION, LSI, SPLIT, SHDI and SHEI can be found in Table 1. Grid_L2, Mountain_L2 and Watershed_L2 represent the different analysis units of the grid, mountain units and watersheds with a size of 2.

Data Records

The LPL3053 is stored in a data repository on Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13999603). The final dataset contains 32.9 GB of data. The details of the files and folders can be found in Supplementary Table S4.

Basic derivatives

The basic derivatives are the derivatives calculated on the basis of the DEM. In this study, the main factors used included slope, AS, TRI, GID, and GDD. Slope is a fundamental factor in geomorphological research. It reflects the degree of inclination of the Earth’s surface and influences the process of material movement on the surface. The method used in this study to calculate the slope is described by Wilson and Gallant54. This method was implemented in ArcGIS software, and the slope was calculated on the basis of a finite difference formula and the elevations of 8 neighbouring cells. The calculation methods for AS, TRI, GID, and GDD are detailed in Sect. 3. All these derivatives have the format of a TIFF 32 bit float and can be found in the folder “BasicDerivatives”. In addition, we provide the boundary of the Loess Plateau (Shpfile polygon) and the corresponding DEM (TIFF 32 bit float) in this folder.

Analysis units

The analysis units refer to the basic computing units used when calculating landform pattern descriptors, including grid units, mountain units, and watershed units. Each type of unit contains four levels of units of different sizes. Among them, L1 represents the largest unit in terms of scale or area. From L1 to L4, the analysis scale gradually becomes finer, and the average area of an individual unit also decreases gradually. Owing to the complexity of the Earth’s surface, at the same level, there may be differences in the areas of individual units among the three different types of units. In the end, 12 analysis unit files are formed as Shpfile polygons and are stored in the folder “AnalysisUnits”.

Landform classification results

As described in Sect. 3, we conducted landform classification from three perspectives. We construct MC, DF and SM results (Fig. 4) and further separate them into more levels (L1 and L2). The landform classification results can be found in the “LC” folder. The formats of these files can be found in Supplementary Table S4.

Landform pattern descriptors

The calculation of landform pattern descriptors for each level of geomorphic classification is a crucial step in understanding the spatial differences among different landform types. These descriptors provide valuable insights into the patterns and characteristics of the landscape. We calculated these indicators for each analysis unit file. This comprehensive approach resulted in a total of 48 shapefiles (Fig. 5), with each file dedicated to all the descriptors calculated on the basis of a specific analysis unit. Within these shapefiles, the attribute table stores the descriptor values for each individual unit feature. The field names in the attribute table correspond to the descriptor abbreviations listed in Table 1, ensuring consistency and clarity in the data organization. All these shapefiles have been stored in the folder “Descriptor”54.

Technical Validation

Assessment of landform classification on the basis of morphological characteristics

This study chose the 1:1000000 digital land geomorphology for China27 as the reference dataset for accuracy assessment. This study is one of the most crucial references for Chinese geomorphologic research and has been widely used in related studies55,56.

As shown in Fig. 6, in the evaluation of the tableland and mountainous results, the regions of Liupan Mountain and Taihang Mountain were chosen as representative areas for tableland and mountainous landforms. A comparison was made between the reference data27 and the classification results of this study. Figure 6 shows the comparative results for Liupan Mountain, Taihang Mountain, and their surrounding areas. In this study we achieved effective refinement of the expression scale, resulting in finer classification results. Moreover, our results reveal more detailed information about the boundaries of landforms, especially in valley areas.

Comparison of classification results between the 1:1000000 digital land geomorphology for China and that in our study. (a,b) are the results for the Taihang Mountain dataset. (c,d) are the results for Liupan Mountain. (a,c) are the results of the 1:1000000 digital land geomorphology for China. (b,d) are the results for LPL30.

Owing to the differences in scale between the reference data and the classification results of this study, a pairwise accuracy comparison was not feasible. Therefore, this study has redesigned the process for quantitatively comparing the results. To evaluate the classification results of plains and hills, this paper constructed a category dominance index (CDI) to represent classification accuracy. The formula for calculating the CDI is as follows:

where Ap represents the total area of a specific patch in the 1:1000000 digital land geomorphology for China for plains or hills and where Ac represents the total area of the classification results of this study that are within the same category as the patch in the 1:1000000 digital land geomorphology for China. The closer this value is to 1, the more consistent the two classification results are. As shown in Fig. 7, when comparing the plain and hill classifications, the classification results of this study are consistent with the reference data.

Assessment of landform classification considering dominant forces

The classification accuracy of gullies and intergullies was evaluated through comparisons with visually interpreted results. In this study, 5000 random points were generated within the Loess Plateau region, and the landform types at each point were visually determined. We compared the visually interpreted results and the classification results of this study (Table 2) to calculate the classification accuracy.

On the basis of the commonly used metrics in classification studies 8, we calculate precision and recall separately on the basis of the results related to gullies and intergullies. Specifically, when analysing gullies, intergullies areas were considered to constitute the background (negative class); when analysing intergullies areas, gullies were considered to constitute the background (negative class). Referring to the number in Table 2, the metric formulas for these two types are shown as follows:

where Pg and Rg represent the precision and recall, respectively, for gullies and where Pi and Ri represent the precision and recall, respectively, for integrated areas. We obtained values of Pg = 0.84, Rg = 0.79, Pi = 0.86, and Ri = 0.90. These results indicate that this study achieved good accuracy for both gullies and intergullies, with accuracies greater than 0.8 for both landform types. The recall for gully areas is slightly lower than that for intergully areas, with the recall for intergully areas reaching 0.9.

Assessment of landform classification incorporating surface material

This section compares the classified results with the visually interpreted results. We also compared our results with those of the DL-based method used in previous research8. As shown in Table 3, while DL performed well in sample areas, its performance might be unsatisfactory when it is applied over larger regions.

Usage Notes

This newly developed dataset has a wide variety of potential applications in revealing landform patterns and exploring landform development. The classification results of the typical loess landforms (SM_L2) provide a more direct representation of loess landform development. Among these, the formation process of loess ridges and loess hills remains a key topic. Studies52,57 indicate that the distribution of loess particles is closely related to the source of loess particles, regional environmental factors (such as precipitation), and palaeogeomorphological distribution. Under the influence of modern erosion, loess ridges potentially exhibit a developmental trend towards loess hills. Water erosion promotes gully development, damages loess ridges and leads to the formation of multiple loess hills. Moreover, palaeogeomorphology also significantly influences the distribution of loess ridges and loess hills. In certain areas, modern landforms may inherit ancient landforms where modern erosion merely accentuates their characteristics without altering their geomorphologic modes. Simultaneously, the source of loess materials determines their thickness and can influence loess landform types. Research 2 suggests that the Loess Plateau mainly comprises material from the northeastern Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau (including substantial desert and Gobi material). To further support the study of loess landform development, we calculated the loess ridge‒hill ratio in various analysis units, i.e., the ratio of the loess ridge area to the loess hill area within a defined unit. The results indicate that the concentration of loess hills in the northwestern region is close to the primary source of loess material. This area is closer to the inland region with less precipitation, suggesting that the loess hill here may have originated from inherited palaeogeomorphology. Additionally, a transition of loess landforms from northwest to southeast occurred, during which the number of loess ridges gradually increased. This transition can be attributed to increased precipitation. Within this region, especially in areas where the interweaving distribution of loess ridge and loess hills occurs, careful inference is necessary regarding the formation of loess hills. Enhanced surface erosion due to increased rainfall might be the primary cause, yet the possibility of loess hills still largely inheriting palaeogeomorphology cannot be discounted. A comprehensive study involving climatic factors, palaeogeomorphology and loess material is needed to further reveal the aridification history, dust emission and accumulation processes in the Asian interior, and the formation of this unique landscape in East Asia2.

Code availability

All procedures in this study are completed via ArcGIS Pro and the corresponding arcpy functions. The main tools include slope, flow direction, flow accumulation and distance accumulation. No custom code was used during this study for the curation and/or validation of the dataset.

References

Liu, D. Loess in China. (Springer, 1988).

Zhang, H. et al. Large-number detrital zircon U-Pb ages reveal global cooling caused the formation of the Chinese Loess Plateau during Late Miocene. Science advances 8, eabq2007, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abq2007 (2022).

Li, Y., Shi, W., Aydin, A., Beroya-Eitner, M. A. & Gao, G. Loess genesis and worldwide distribution. Earth-Science Reviews 201, 102947 (2020).

Lu, H. et al. Chinese loess and the Asian monsoon: What we know and what remains unknown. Quaternary International 620, 85–97, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2021.04.027 (2022).

Xiong, L. et al. Geomorphological inheritance for loess landform evolution in a severe soil erosion region of Loess Plateau of China based on digital elevation models. Science China Earth Sciences 57, 1944–1952, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11430-014-4833-4 (2014).

Xiong, L. & Tang, G. Simulating Loess with Underlying Bedrock Paleotopographic strata for Landscape Evolution in the Loess Plateau Based on Digital Elevation Models (2013).

Liu, K. et al. Large-scale mapping of gully-affected areas: An approach integrating Google Earth images and terrain skeleton information. Geomorphology 314, 13–26, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2018.04.011 (2018).

Li, S., Xiong, L., Tang, G. & Strobl, J. Deep learning-based approach for landform classification from integrated data sources of digital elevation model and imagery. Geomorphology, 107045, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2020.107045 (2020).

Yang, M.-Y., Tian, J.-L. & Liu, P.-L. Investigating the spatial distribution of soil erosion and deposition in a small catchment on the Loess Plateau of China, using 137Cs. Soil and Tillage Research 87, 186–193, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2005.03.010 (2006).

Pye, K. Aeolian dust and dust deposits. (Elsevier, 2015).

Tang, G., Li, F., Liu, X., Long, Y. & Yang, X. Research on the slope spectrum of the Loess Plateau. Science in China Series E: Technological Sciences 51, 175–185, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11431-008-5002-9 (2008).

Fu, B. & Chen, L. Agricultural landscape spatial pattern analysis in the semi-arid hill area of the Loess Plateau, China. Journal of Arid Environments 44, 291–303, https://doi.org/10.1006/jare.1999.0600 (2000).

Fu, B. Soil erosion and its control in the Loess Plateau of China. Soil Use and Management 5, 76–82, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-2743.1989.tb00765.x (1989).

Fu, B., Chen, L., Ma, K., Zhou, H. & Wang, J. The relationships between land use and soil conditions in the hilly area of the loess plateau in northern Shaanxi, China. Catena 39, 69–78, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0341-8162(99)00084-3 (2000).

Wang, T. et al. Ecologically asynchronous agricultural practice erodes sustainability of the Loess Plateau of China. Ecological Applications 20, 1126–1135, https://doi.org/10.1890/09-0229.1 (2010).

Fu, B. et al. Hydrogeomorphic ecosystem responses to natural and anthropogenic changes in the Loess Plateau of China. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 45, 223–243, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-earth-063016-020552 (2017).

Tsunekawa, A., Liu, G., Yamanaka, N. & Du, S. Restoration and development of the degraded Loess Plateau, China. (Springer, 2014).

Lu, F. et al. Effects of national ecological restoration projects on carbon sequestration in China from 2001 to 2010. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115, 4039–4044, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1700294115 (2018).

Zhu, Y., Jia, X. & Shao, M. Loess thickness variations across the Loess Plateau of China. Surveys in Geophysics 39, 715–727, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10712-018-9462-6 (2018).

Zhou, Y. et al. Positive and negative terrains on northern Shaanxi Loess Plateau. Journal of Geographical Sciences 20, 64–76, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11442-010-0064-6 (2010).

Li, S., Yang, X., Zhou, X. & Tang, G. Quantification of Surface Pattern Based on the Binary Terrain Structure in Mountainous Areas. Remote Sensing 15, 2664, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs15102664 (2023).

Liu, K. et al. Large-scale detection of the tableland areas and erosion-vulnerable hotspots on the Chinese Loess Plateau. Remote Sensing 14, 1946, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14081946 (2022).

Yuan, S. et al. Loess tableland geomorphic classification criteria and evolutionary pattern using multiple geomorphic parameters. Catena 217, 106493, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2022.106493 (2022).

Drăguţ, L. & Eisank, C. Automated object-based classification of topography from SRTM data. Geomorphology 141, 21–33, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2011.12.001 (2012).

Iwahashi, J., Kamiya, I., Matsuoka, M. & Yamazaki, D. Global terrain classification using 280 m DEMs: segmentation, clustering, and reclassification. Progress in Earth and Planetary Science 5, 1–31, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40645-017-0157-2 (2018).

Iwahashi, J. & Yamazaki, D. Global polygons for terrain classification divided into uniform slopes and basins. Progress in Earth and Planetary Science 9, 33, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40645-022-00487-2 (2022).

Zhou, C., Cheng, W., Qian, J., Li, B. & Zhang, B. Research on the classification system of digital land geomorphology of 1: 1000000 in China. Journal of Geo-Information Science 11, 707–724, https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1047.2009.00707 (2009).

Theobald, D. M., Harrison-Atlas, D., Monahan, W. B. & Albano, C. M. Ecologically-relevant maps of landforms and physiographic diversity for climate adaptation planning. PloS one 10, e0143619, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0143619 (2015).

Xiong, L., Li, S., Tang, G. & Strobl, J. Geomorphometry and terrain analysis: data, methods, platforms and applications. Earth-Science Reviews, 104191, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2022.104191 (2022).

Wilson, J. P. Environmental applications of digital terrain modeling. (John Wiley & Sons, 2018).

Maxwell, A. E. & Shobe, C. M. Land-surface parameters for spatial predictive mapping and modeling. Earth-Science Reviews 226, 103944, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2022.103944 (2022).

Yan, S.-J., Tang, G. A., Li, F.-Y. & Zhang, L. Snake model for the extraction of loess shoulder-line from DEMs. Journal of Mountain Science 11, 1552–1559, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11629-013-2484-0 (2014).

Derbyshire, E. Geological hazards in loess terrain, with particular reference to the loess regions of China. Earth-Science Reviews 54, 231–260 (2001).

Sun, J. Provenance of loess material and formation of loess deposits on the Chinese Loess Plateau. Earth and planetary science letters 203, 845–859 (2002).

Hawker, L. et al. A 30 m global map of elevation with forests and buildings removed. Environmental Research Letters 17, 024016, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ac4d4f (2022).

Gregory, K. J. Fluvial processes in British basins: The impact of hydrology and the prospect for hydrogeomorphology In Geomorphology: Present problems and future prospects. 40–72 (Oxford University Press, 1978).

Evans, I. S. Geomorphometry and landform mapping: What is a landform? Geomorphology 137, 94–106, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2010.09.029 (2012).

Qin, C. et al. An adaptive approach to selecting a flow‐partition exponent for a multiple‐flow‐direction algorithm. International Journal of Geographical Information Science 21, 443–458, https://doi.org/10.1080/13658810601073240 (2007).

Renard, K. G., Foster, G. R., Weesies, G. A. & Porter, J. P. RUSLE: Revised universal soil loss equation. Journal of soil and Water Conservation 46, 30–33 (1991).

Shi, K. et al. Satellite remote sensing data reveal increased slope climbing of urban land expansion worldwide. Landscape and Urban Planning 235, 104755, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2023.104755 (2023).

Xiong, L., Tang, G., Yang, X. & Li, F. Geomorphology-oriented digital terrain analysis: Progress and perspectives. Journal of Geographical Sciences 31, 456–476, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11442-021-1853-9 (2021).

Leger, M. Loess landforms. Quaternary International 7, 53–61, https://doi.org/10.1016/1040-6182(90)90038-6 (1990).

Maxwell, A. E. & Shobe, C. M. Land-surface parameters for spatial predictive mapping and modeling. Earth-Science Reviews: The International Geological Journal Bridging the Gap between Research Articles and Textbooks, 226 (2022).

Rennó, C. D. et al. HAND, a new terrain descriptor using SRTM-DEM: Mapping terra-firme rainforest environments in Amazonia. Remote Sensing of Environment 112, 3469–3481 (2008).

Li, M. et al. Identifying sediment sources from the inter-gully area and gully area in a small watershed in the Loess Hilly Region of China. Environmental Earth Sciences 76, 1–11 (2017).

Valentin, C., Poesen, J. & Li, Y. Gully erosion: Impacts, factors and control. Catena 63, 132–153 (2005).

Zhu, H., Tang, G., Qian, K. & Liu, H. Extraction and analysis of gully head of Loess Plateau in China based on digital elevation model. Chinese geographical science 24, 328–338 (2014).

Sechu, G. L. et al. A stepwise GIS approach for the delineation of river valley bottom within drainage basins using a cost distance accumulation analysis. Water 13, 827, https://doi.org/10.3390/w13060827 (2021).

Liu, K. et al. Detection of catchment-scale gully-affected areas using unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) on the Chinese Loess Plateau. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 5, 238, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi5120238 (2016).

Elsner, J. B., Hodges, R. E. & Jagger, T. H. Spatial grids for hurricane climate research. Climate dynamics 39, 21–36 (2012).

Chen, Y. et al. Relationship between urban spatial form and seasonal land surface temperature under different grid scales. Sustainable Cities and Society 89, 104374 (2023).

Xiong, L. et al. Paleotopographic controls on modern gully evolution in the loess landforms of China. Science China Earth Sciences 60, 438–451, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11430-016-0211-5 (2017).

Li, S. et al. LPL30-A multilevel dataset of landform mapping and geomorphologic descriptors for the Loess Plateau of China. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10369273 (2024).

Wilson, J. P. & Gallant, J. C. Terrain analysis: principles and applications. (John Wiley & Sons, 2000).

Ouyang, S. et al. A fine-grained genetic landform classification network based on multimodal feature extraction and regional geological context. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 60, 1–14, https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2022.3203606 (2022).

Lin, S. & Chen, N. Employment of Continuous Slope Cumulative Frequency Spectrum in geomorphology quantitative analysis–a case study on Loess Plateau. Geomorphology 415, 108405, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2022.108405 (2022).

Luo, L. A tentative classification of landforms in the Loess Plateau. Acta Geogr Sin 22, 201–222 (1956).

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42401507; 41930102; 42371407; 42171402; 42271421), Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions, and the Deep-time Digital Earth (DDE) Big Science Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.L., L.X. and G.T. designed the study. S.L., L.X. and Y.L. performed the experiment. S.L. and L.X. wrote the first version of the manuscript. X.Y. and F.L. coordinated the work and reviewed the manuscript. S.L. and Y.L. assisted with quality control and reviewed the manuscript. All the authors contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, S., Xiong, L., Li, Y. et al. A multilevel dataset of landform mapping and geomorphologic descriptors for the Loess Plateau of China. Sci Data 11, 1282 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-04027-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-04027-z

This article is cited by

-

A new approach for landform classification based on geomorphic entity objects: a case study on the Tibetan Plateau

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

A global scale submarine landform dataset driven by terrain knowledge

Scientific Data (2025)

-

Effects of dry–wet cycles on the dynamic characteristics of cement-stabilized loess

Bulletin of Engineering Geology and the Environment (2025)