Abstract

Fungi from the Pyricularia genus cause blast disease in many economically important crops and grasses, such as wheat, rice, and Cenchrus grass JUJUNCAO. Structure variation associated with the gain and loss of effectors contributes largely to the adaptive evolution of this fungus towards diverse host plants. A telomere-to-telomere genome assembly would facilitate the identification of genome-wide structural variations through comparative genomics. Here, we report a telomere-to-telomere, near-complete genome assembly of a Pyricularia penniseti isolate JC-1 infecting JUJUNCAO. The assembly consists of eight core chromosomes and two supernumerary chromosomes, named mini1 and mini2, spanning 42.1 Mb. We annotated 12,156 protein-coding genes and identified 4.54% of the genome as repetitive sequences. The two supernumerary chromosomes contained fewer genes and more repetitive sequences than the core chromosomes. Our genome and results provide valuable resources for the future study in genome evolution, structure variation and host adaptation of the Pyricularia fungus.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Fungi from the Pyricularia genus can infect a variety of grasses1. Among them, Pyricularia oryzae (syn. Magnaporthe oryzae)2 is known to infect a wide range of grass hosts, and cause devastating blast disease on economically important crops, such as rice and wheat3. The pathogenicity of blast fungus was primarily determined by effectors4,5,6. The gain and loss of effector genes, along with genome structural variations associated with host adaptation, are largely mediated by the transposable elements (TEs)7,8,9. A high-quality reference genome would facilitate understanding of genome plasticity partially mediated by TEs, tracing the evolution trajectories associated with host jump and host adaptation of these pathogenic fungi, while also benefiting durable control of the blast disease10. In the past decades, the genomes of hundreds of the field isolates had been sequenced and analyzed11,12,13,14. However, genomes assembled using Illumina short reads are not qualified for identification of structure variations, particularly complex regions enriched with repetitive elements7. Following the first assembly of Guy11 genome using PacBio long reads from our lab7, several high-quality genomes from the Pyricularia genus have been reported15,16,17,18, but only one telomere-to-telomere genome of the rice blast isolate P131 had been published recently19. To date, seven core chromosomes have been identified in the Pyricularia isolates16,19. Most of these studies focused on the rice- and wheat-infecting isolates, while the genome structure of blast fungus infecting other hosts remains largely unknown. Previously, the genome of P1609, a P. penniseti isolate infecting the Cenchrus grass JUJUNCAO20, was assembled into 53 contigs using the long-read PacBio technology. Comparative genomic analysis between P. penniseti and P. oryzae revealed a rapid divergence in the repertoire of pathogenicity-associated genes21.

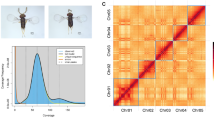

In this study, we generated a telomere-to-telomere and near-complete genome assembly of a new P. penniseti isolate JC-1, which showed higher performance in conidiation and protoplast production than P1609. The genome of JC-1 was sequenced using the Oxford Nanopore Ultra-Long protocol, generating 27.7 Gb of reads (~650 × genome coverage; Table 1), and was assembled with Canu v2.222. The assembly was polished with 4.45 Gb of Illumina short reads (~110 × genome coverage; Table 1). The final assembly includes 10 chromosomes, spanning 42.1 Mb (Tables 2, 3; Fig. 1). Of the 10 chromosomes, all contain telomere repeats at both ends, except for chr1, which is missing a telomere on the left end. This missing telomere is likely due to the assembly challenges posed by the highly repetitive nucleolar organizer region (NOR)23, which is known for its tandem repeats of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes24 (Fig. 1, Track A). In the final assembly, 31 copies of 18S rDNA spanning about 250 kb were identified. The genome of the P. penniseti isolate JC-1 contains eight chromosomes sharing high collinearity with the seven core chromosomes of the P. oryzae isolate 70-15, indicative of eight core chromosomes in JC-1 genome (chr1-8; Fig. 1). Notably, the size of chr5 and chr7 (~2.0 Mb) was much less than the other core chromosomes of JC-1 (Figs. 1, 2). In addition, we also identified two small assembled chromosomes, which share low collinearity with the core chromosomes of P. oryzae isolate 70-15 and referred to as supernumerary chromosomes (mini1 and mini2; Fig. 1). Therefore, the P. penniseti isolate JC-1 assembly contains eight core chromosomes and two supernumerary mini-chromosomes. To further confirm whether the eight core chromosomes are common in the P. penniseti isolates, we performed Pulsed Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE) to assess the karyotype of four P. penniseti isolates collected from different areas (JC-1 to JC-4) and the P. oryzae isolate Guy11 without mini-chromosome. The PFGE result showed that all the four P. penniseti isolates displayed two bands (between 1.81–2.35 Mb) representing the two small core chromosomes, as well as the two supernumerary mini-chromosomes (mini1 and mini2) with varied sizes in each isolate (Table 3; Fig. 2). The completeness of the P. penniseti isolate JC-1 genome assembly was estimated to be 97.7% using single-copy, conserved genes (benchmarking universal single-copy orthologs (BUSCO; Table 2). The assembled genome encoded 12,156 genes and contained 4.54% repetitive sequences (Tables 2–4). The content of repetitive sequences in JC-1 was lower than that in rice-infecting P. oryzae isolates (>10%), but was comparable to non-rice-infecting P. oryzae isolates (~5%)9. The JC-1 assembly showed a high contiguity for contigs N50 (6.6 Mb; Table 2) and 19 telomeres (Fig. 1). The two supernumerary mini-chromosomes contained fewer genes and significantly more repetitive sequences than the core chromosomes (Fig. 3a,b). The JC-1 assembly should serve as a new high-quality reference genome for the application of comparative and functional genomics in genome evolution, structural variation, and host adaptation among Pyricularia isolates infecting diverse hosts.

Methods

Fungal strains

The Pyricularia penniseti strain JC-1 was isolated from the leaf spot lesion on JUJUNCAO (Cenchrus fungigraminus; syn. Pennisetum giganteum Z. X. Lin)18, and is stored at the Fujian Universities Key Laboratory for Plant-Microbe Interaction, Fuzhou, Fujian Province, China. For fugal growth, the JC-1 strain was incubated on solid complete medium (CM) at 28 °C in the dark.

Sampling and DNA extraction

The P. penniseti isolate JC-1 was cultured in liquid complete medium (CM) at 110 rpm, 28 °C for 3 days. The mycelia were collected and washed twice using ddH2O. Genomic DNA was extracted from vegetative mycelia and used for genome sequencing as described previously by Zhong et al.14.

Nanopore and Illumina Whole Genome Sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted using the GP1 method (Novogene, Beijing, China) and 100 kb size selection was performed using the SageHLS HMW library system (Sage Science) high pass protocol. An ultra-long library protocol was prepared following the SQK-LSK114 protocol (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, UK). A tatal of 400 ng of DNA libraries were loaded to R10.4.1 flow cell and sequenced on the PromethION platform (Oxford Nanopore Technologies) at the Novogene Bioinformatics Technology Co., Ltd (Beijing, China). For Illumina sequencing, the library was constructed and sequenced on Illumina NovaSeq6000 platform at Novogene Bioinformatics Technology Co., Ltd (Beijing, China).

Genome assembly

The raw nanopore long reads of JC-1 were assembled using Canu v2.224 with the following parameters: useGrid = false genomeSize = 45 m minReadLength = 5000 minOverlapLength = 2000 corOutCoverage = 60 correctedErrorRate = 0.1 corPartitionMin = 10000 maxInputCoverage = 100. Total of 11 assembled contigs were polished with Illumina short-read sequencing data using NextPolish v1.4.125 for three rounds.

Evaluation of the genome assembly

To detect telomeres on the chromosome, sequence TTAGGG/CCCTAA (as reported byBrigati et al.26) was aligned to JC-1 assembly using the TIDK v.0.2.027 with the following parameters: tidk explore–minmum 5–maximum 12 genome.fa tidk search–string TTTAGGG–dir outdir–output output genome. For visualization, the following parameters were used: tidk plot –tsv windows.tsv. The genome assembly quality was evaluated through the BUSCO (Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs) v5.5.028 tool with the “ascomycota_odb10” lineage as a reference dataset.

Generation of annotations

Protein-coding genes were annotated using the Braker 2.0 v2.1.629, which integrates both ab initio gene predictions generated by AUGUSTUS v3.4.030 and GeneMark-EP +31, as well as homology evidence from fungi protein sequences in the OrthoDB fungal database. All high-confidence protein-coding genes predicted by Braker 2.0 were used for statistic and comparative genome analysis in this study.

An ab initio transposable element (TE) library was constructed using RepeatModeler v1.0.832 with default parameters. RepeatMasker v3.3.033 was applied to perform a homology-based repeat search throughout the whole JC-1 genome using the constructed TE library.

Pulsed Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE)

Protoplast plug was prepared using the CHEF (Contour-clamped homogeneous electric field) Genomic DNA Plug Kits (Bio-Rad, California, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. In brief, the mycelia was collected and digested with 10 mg/mL Lysing Enzymes in 1 M sorbitol at 30 °C, 85 rpm for 3 h. The digested product was filtered through sterile Nytex nylon mesh that has a 25 µm pore size34 and centrifuged at 4,500 rpm, 4 °C for 10 min to collect the protoplasts. The protoplasts were washed with SE buffer (1 M sorbitol, 50 mM EDTA) and adjusted to a concentration of 1 × 109 protoplast/ml, then mixed with 2% low melting agarose gel (Bio-Rad, California, USA) and transferred to modules to form protoplast plugs. The protoplast plugs were transferred to a 10 ml tube containing proteinase K buffer and incubate overnight at 50 °C in water bath without agitation. After four wash with 1 × wash buffer at 25 °C, the plugs were immersed in 0.5 × TBE and stored at 4 °C. CHEF gel electrophoresis was conducted according to Orbach et al.34 with minor modifications. In brief, chromosomes were separated using a CHEF-DRII System (Bio-Rad, California, USA) on 1% Certified Megabase Agarose in 0.5 × TBE buffer at 2 V/cm, 14 °C, with a switching interval of 900 s for 96 h. The 0.5 × TBE buffer was replaced every two days.

Classification of mini- and core-chromosome assemblies

To classify the mini- and core-chromosome assemblies, macrosynteny relationships between JC-1 and the 70-15 (P. oryzae) reference genome were identified and plotted based on the results of MCScanX35 with default parameters. Finally, gene frequency, distribution of TEs, and collinear gene pairs between JC-1 and 70-15 were visualized using advanced Circos plots generated with TBtools-II v2.08636.

Data Records

The raw Oxford illumina data and Nanopore sequencing data have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) under the BioProject (PRJNA1146787) with accession number of SRR3020789937 and SRR3020790038, respectively. The genome assembly was deposited under the same BioProject at NCBI, under the accession number JBGNXE000000000.139.

Technical Validation

Quality control of the Nanopore Ultra-Long reads was performed using NanoPack2 (https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btad311). The N50 read lenth for the Nanopore Ultra-Long reads length was 100 kb, with an average Q score of 13.2. The Illumina sequencing reads were found to have a GC content of 49.06%, with 96.96% and 92.00% of reads having quality scores of 20 and 30, respectively. The chromosome-level genome assembly has a size of 42.1 Mb, and the contig N50 length is 6.64 Mb. The genome completeness was evaluated using BUSCO (Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs) v5.5.028 with the ascomycota_odb10 database. The results showed the following BUSCO statistics: 97.7% complete, 97.2% complete single-copy, 0.5% duplicated, 0.3% fragmented, and 2.0% missing (Table 2). Telomeres were detected on each chromosome using TIDK v.0.2.027 employing the telomeric sequence (TTAGGG/CCCTAA)26, and the results show that each chromosome contains telomeres. In conclusion, these results indicate high completeness of our JC-1 genome assembly.

Code availability

In this study, no custom scripts or customized command lines were used. All comparative analyses were performed using publicly available software. The Methods section provides detailed information about the versions and parameters of each software tool used. Where specific parameters were not mentioned for a given software, the default settings were applied. The application of these software tools adhered strictly to the manuals and protocols provided by the respective bioinformatics resources.

References

Klaubauf, S. et al. Resolving the polyphyletic nature of Pyricularia (Pyriculariaceae). Studies in mycology 79, 85–120, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.simyco.2014.09.004 (2014).

Zhang, N. et al. Generic names in Magnaporthales. IMA fungus 7, 155–159, https://doi.org/10.5598/imafungus.2016.07.01.09 (2016).

Valent, B. The impact of blast disease: past, present, and future. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J.) 2356, 1–18, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-1613-0_1 (2021).

Giraldo, M. C. & Valent, B. Filamentous plant pathogen effectors in action. Nature reviews. Microbiology 11, 800–814, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro3119 (2013).

Oliveira-Garcia, E., Yan, X., Oses-Ruiz, M., de Paula, S. & Talbot, N. J. Effector-triggered susceptibility by the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. The New phytologist 241, 1007–1020, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.19446 (2024).

Wei, Y. Y., Liang, S., Zhu, X. M., Liu, X. H. & Lin, F. C. Recent advances in effector research of Magnaporthe oryzae. Biomolecules 13, https://doi.org/10.3390/biom13111650 (2023).

Bao, J. et al. PacBio sequencing reveals transposable elements as a key contributor to genomic plasticity and virulence variation in Magnaporthe oryzae. Molecular plant 10, 1465–1468, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molp.2017.08.008 (2017).

Yoshida, K. et al. Host specialization of the blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae is associated with dynamic gain and loss of genes linked to transposable elements. BMC genomics 17, 370, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-016-2690-6 (2016).

Lin, L. et al. Transposable elements impact the population divergence of rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. mBio, e0008624, https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio.00086-24 (2024).

Langner, T., Białas, A. & Kamoun, S. The blast fungus decoded: genomes in flux. mBio 9, https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.00571-18 (2018).

Gladieux, P. et al. Gene flow between divergent cereal- and grass-specific lineages of the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. mBio 9, https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.01219-17 (2018).

Dean, R. A. et al. The genome sequence of the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea. Nature 434, 980–986, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature03449 (2005).

Dong, Y. et al. Global genome and transcriptome analyses of Magnaporthe oryzae epidemic isolate 98-06 uncover novel effectors and pathogenicity-related genes, revealing gene gain and lose dynamics in genome evolution. PLoS pathogens 11, e1004801, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1004801 (2015).

Zhong, Z. et al. Population genomic analysis of the rice blast fungus reveals specific events associated with expansion of three main clades. The ISME journal 12, 1867–1878, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-018-0100-6 (2018).

Wang, Y. et al. Genome sequence of Magnaporthe oryzae EA18 virulent to multiple widely used rice varieties. Molecular plant-microbe interactions: MPMI 35, 727–730, https://doi.org/10.1094/mpmi-01-22-0030-a (2022).

Peng, Z. et al. Effector gene reshuffling involves dispensable mini-chromosomes in the wheat blast fungus. PLoS genetics 15, e1008272, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1008272 (2019).

Langner, T. et al. Genomic rearrangements generate hypervariable mini-chromosomes in host-specific isolates of the blast fungus. PLoS genetics 17, e1009386, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1009386 (2021).

Gómez Luciano, L. B. et al. Blast fungal genomes show frequent chromosomal changes, gene gains and losses, and effector gene turnover. Molecular biology and evolution 36, 1148–1161, https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msz045 (2019).

Li, Z. et al. First telomere-to-telomere gapless assembly of the rice blast fungus Pyricularia oryzae. Scientific data 11, 380, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03209-z (2024).

Zheng, H. et al. A near-complete genome assembly of the allotetrapolyploid Cenchrus fungigraminus (JUJUNCAO) provides insights into its evolution and C4 photosynthesis. Plant communications 4, 100633, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xplc.2023.100633 (2023).

Zheng, H. et al. Comparative genomic analysis revealed rapid differentiation in the pathogenicity-related gene repertoires between Pyricularia oryzae and Pyricularia penniseti isolated from a Pennisetum grass. BMC genomics 19, 927, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-018-5222-8 (2018).

Koren, S. et al. Canu: scalable and accurate long-read assembly via adaptive k-mer weighting and repeat separation. Genome research 27, 722–736, https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.215087.116 (2017).

Skinner, D. Z. et al. Genome organization of Magnaporthe grisea: genetic map, electrophoretic karyotype, and occurrence of repeated DNAs. TAG. Theoretical and applied genetics. Theoretische und angewandte Genetik 87, 545–557, https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00221877 (1993).

Rehmeyer, C. et al. Organization of chromosome ends in the rice blast fungus, Magnaporthe oryzae. Nucleic acids research 34, 4685–4701, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkl588 (2006).

Hu, J., Fan, J., Sun, Z. & Liu, S. NextPolish: a fast and efficient genome polishing tool for long-read assembly. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 36, 2253–2255, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btz891 (2020).

Brigati, C., Kurtz, S., Balderes, D., Vidali, G. & Shore, D. An essential yeast gene encoding a TTAGGG repeat-binding protein. Molecular and cellular biology 13, 1306–1314, https://doi.org/10.1128/mcb.13.2.1306-1314.1993 (1993).

Kanzaki, H. et al. Arms race co-evolution of Magnaporthe oryzae AVR-Pik and rice Pik genes driven by their physical interactions. The Plant journal: for cell and molecular biology 72, 894–907, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.05110.x (2012).

Simão, F. A., Waterhouse, R. M., Ioannidis, P., Kriventseva, E. V. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 31, 3210–3212, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351 (2015).

Brůna, T., Hoff, K. J., Lomsadze, A., Stanke, M. & Borodovsky, M. BRAKER2: automatic eukaryotic genome annotation with GeneMark-EP+ and AUGUSTUS supported by a protein database. NAR genomics and bioinformatics 3, lqaa108, https://doi.org/10.1093/nargab/lqaa108 (2021).

Keller, O., Kollmar, M., Stanke, M. & Waack, S. A novel hybrid gene prediction method employing protein multiple sequence alignments. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 27, 757–763, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btr010 (2011).

Brůna, T., Lomsadze, A. & Borodovsky, M. GeneMark-EP+: eukaryotic gene prediction with self-training in the space of genes and proteins. NAR genomics and bioinformatics 2, lqaa026, https://doi.org/10.1093/nargab/lqaa026 (2020).

Flynn, J. M. et al. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 117, 9451–9457, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1921046117 (2020).

Tarailo-Graovac, M. & Chen, N. Using RepeatMasker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. 25, 4.10.11-14.10.14, https://doi.org/10.1002/0471250953.bi0410s25 (2009).

Orbach, M. J., Chumley, F. G. & Valent, B. Electrophoretic karyotypes of Magnaporthe grisea pathogens of diverse grasses. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions 9, 261–271 (1996).

Wang, Y. et al. MCScanX: a toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic acids research 40, e49, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkr1293 (2012).

Chen, C. et al. TBtools-II: A “one for all, all for one” bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Molecular plant 16, 1733–1742, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molp.2023.09.010 (2023).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR30207900 (2024).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR30207899 (2024).

NCBI Genbank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc:JBGNXE000000000 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32172365 and 32272513).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.Z., X.Li., B.W. and Z.W. conceived and designed the project. Y.L., X.Lian, and X.W. collected the samples. Y.L., X.W. and J.H. assembled and polished genome. Y.L., and X.W. conducted protein-coding gene and repetitive sequence annotations. Y.L., X.W., and Z.F. performed comparative genomic analysis. X.Li., and G. Lin. assisted in data analysis. H.Z. and X.Li. drafted the manuscript. Z.W., B.W. and G.Lu. revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Wang, X., Huang, J. et al. Near complete assembly of Pyricularia penniseti infecting Cenchrus grass identified its eight core chromosomes. Sci Data 11, 1186 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-04035-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-04035-z