Abstract

In the Antarctic, Arctic, and Tibetan Plateau—recognized as the Earth’s three poles characterized by extremely harsh environments—lichens prevail in the ecosystem and play crucial roles as pioneer species. Despite their importance, studies investigating the spatial distribution patterns of lichen attributes are scarce due to a lack of appropriate datasets. To bridge this gap and enhance our understanding of the growth preferences of lichens in these areas, here we present a geospatial dataset encompassing key attributes of lichens, such as color type and growth form, for over 2800 lichen species and 170,000 in-situ lichen records. The dataset facilitates the creation of the first spatial distribution map illustrating the variation of lichen attributes across different latitudes and longitudes. This can serve as a foundational resource for studies on the relationship between lichen types and their growing environment, which is a vital scientific question in the ecology domain. Additionally, it can contribute to the development of specialized remote sensing technique tailored for lichen monitoring, which is currently lacking.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Lichens are composite organisms, comprising algae or cyanobacteria coexisting with filamentous fungi species within a mutualistic relationship1. These entities showcase remarkable stress tolerance, considerable longevity, slow growth rates, and an inherent adaptability that allows them to thrive in the harshest of environments1,2,3. These unique set of attributes enables their growth and reproduction in the world’s most extreme environments, including the Antarctic, Arctic, and Tibetan Plateau—essentially Earth’s three poles, where conventional plant life struggles to survive4. Lichens are recognized as “pioneer species” due to their ability to weather rock surfaces through the secretion of lichen acids, thereby creating favourable conditions for the growth of higher plants5,6,7,8. They also play pivotal roles in ecosystem establishment, nutrient cycling, and carbon sequestration, supporting the maintenance of biodiversity and ecosystem stability within polar regions8,9,10. Therefore, understanding the lichen distribution and its anticipated changes in response to climate variations holds significant importance in predicting the future of ecosystems and environments in the three poles.

A substantial body of literature delves into the diversity of lichen species in the Earth’s three poles. Comprehensive reviews by Bliss11, Markova12, and Pickard and Seppelt13 have provided meticulous insights into the ecological zones of polar regions, encompassing lichen flora and its spatial distribution in both the Arctic and Antarctic. Thomson and Scotter conducted an exhaustive survey of lichens in various Arctic regions, including the Great Slave Lake region, Bathurst Inlet region, Bylot and Northern Baffin Islands, Eastern Axel Heiberg Island, the Fosheim Peninsula, and the Cape Parry and Melville Hills14,15,16,17,18. Thomson’s two volumes on Arctic lichens in the U.S. and Canadian regions cover 965 lichen species19,20. Kristinsson et al. compiled a pan-Arctic lichen checklist spanning 31 regions, including Wrangel Island, Baffin Island, Labrador, Greenland, Jan Mayen, and Arctic Norway, documenting various lichen species21. Paulina et al. investigated lichen diversity on glacier moraines in Svalbard (Longyearbreen, Rieperbreen, and Irenebreen), identifying 135 lichen species22. They also compared lichen composition and richness across these sites. Øvstedal and Smith conducted detailed research on the taxonomy and identification of Antarctic lichens, cataloging over 400 species23. On Livingston Island in the South Shetland Islands, Antarctica, Sancho reported the presence of 108 lichen species24, while Søchting et al. reported 187 lichen species from the same area25. Research efforts focused on the lichen flora of the Tibetan Plateau have predominantly been spearheaded by Chinese scientists, with the publication Lichens of Xizang cataloging a total of 194 lichen species26.

Across these discovered species, lichens exhibit a remarkable diversity in appearance, and understanding how their functional traits vary with climate and habitat availability is crucial for predicting community responses to climate change. For example, lichens display a diverse array of colors, ranging from orange, yellow, red, to green, gray, brown, and black27,28. Colors other than green often result from secondary metabolites that provide various self-protective abilities, such as shielding against sunlight and deterring consumption by animals29. The colors of lichens impact their albedo, which is linked to the absorption of energy30 and ultimately influences their wider distribution31,32. Lichens also show different thallus size, shape, and growth patterns33 intricately linked with their growth rates, ecological functions, and nutrient requirements5,34,35. Lichens morphological features are primarily governed by the mycobiont, which are commonly classified into crustose, foliose, and fruticose1,36, while additional forms such as gelatinous and structureless were also documented in the literature36,37,38. Significant positive correlations have been observed between lichen growth forms and environmental factors39,40,41,42,43,44,45. For example, on the Tibetan Plateau, studies revealed a linear decline in species diversity for crustose and fruticose lichens with increasing elevation, while foliose lichens showed a cubic decline. However, most studies on lichen traits have been limited to specific local regions. This is mainly due to the variation in attribute kinds and definitions addressed across different studies. Moreover, the diverse range of lichen colors and growth forms also presents challenges in creating a comprehensive lichen trait dictionary. More standardized and integrative lichen trait frameworks are needed to support research on lichen stress resistance, responses to climate change, and to enhance remote sensing information extraction of lichens43,46 across large areas, including the three poles.

To facilitate a large-scale analysis of lichens, we meticulously selected and defined two key attributes: color type and growth form. This dataset allows for the investigation of the relationship between lichen types, categorized these attributes, and their respective growing environments—a topic of keen interest to ecologists. Furthermore, it facilitates the assessment of their tolerance levels to various extreme climates, determining their survival possibility under climate change scenarios. Considering the close relationship of these two attributes to surface reflection, our dataset also has the potential to drive advancements in remotely sensed detection techniques for lichen populations. This may enable timely and large-scale monitoring of lichens in the future.

Methods

To develop the geospatial dataset, we initially defined two lichen attributes: color type and growth form. These attributes were chosen due to their significant correlation with lichen physiological and biochemical characteristics, as well as their association with reflection spectra. Here is the workflow (Fig. 1).

Define the two lichen attributes

The attributes of lichens play a crucial role in shaping their adaptability to varied environments, establishing their significance as environmental indicators, and serving as distinctive features for identification. This article specifically concentrates on the color type and growth form of lichens.

Color type

Considering their distinct roles in heat regulation and the protective qualities of similar secondary metabolites, we have classified lichen colors into four groups: pale, green, bright, and dark, defining the color type attribute (Table 1). The pale type includes lichens exhibiting white, gray, or yellowish-gray hues, typically containing lobaric acid, usnic acid, and norstictic acid, recognized for their antibacterial and antioxidant properties32. The green type comprises lichens lacking colorful secondary compounds, appearing green when wet and grayish-green when dry. The bright type encompasses lichens showcasing vivid yellow, orange, and red colors, often producing compounds such as parietin, pinastric acid, vulpinic acid, known for their vibrant colors and antioxidant properties. The dark type refers to lichens in brown or black shades, primarily attributed to melanins, stictic acid, and gyrophoric acid. It’s important to note that the colors of lichens are also influenced by their moisture content. When lichens are wet, the photobiont layer (algae or cyanobacteria) dominates the observed color, as moisture renders the cortex more transparent. In contrast, the color of secondary compounds becomes more prominent when lichens are dry. In this paper, the color type is defined with respect to the dry state of lichens.

Growth form

We employed the classification guidelines established by Hale36 to systematically categorize these growth forms into crustose, foliose, and fruticose (Table 2). Crustose lichens are notably short, lack a lower cortex, and typically adhere tightly to the substrate, resembling a coat or paint4,47. Separating them from the substrate without causing damage can be challenging, and they can contribute to rock weathering through physical processes involving hyphal penetration, as well as expansion/contraction of the lichen thallus, along with chemical processes via the release of various organic acids48. Foliose lichens possess flat, leaf-like lobes, are generally larger, and are less firmly attached to the substrate compared to crustose lichens4. The lobes of these lichens may overlap, resembling tiles, and the lower surface often features a tomentum or anchoring rhizinae, creating favorable microclimates and microhabitats for invertebrates4. Fruticose lichens display a bush-like, strap-shaped, or shrubby appearance, with the primary axis ranging from prostrate to erect. They commonly branch and are attached to the substrate by basal rhizoids47. Due to their dense thallus and complex vertical structures, they can regulate the temperature and humidity of their surroundings, providing roosting, living, and breeding spaces for other organisms1. It’s important to note that although lichen growth rate is often expressed as a linear measure (mm y−1), the meanings differ for the three growth forms. For foliose and crustose lichens, it indicates an increased radius, while for fruticose species, it represents increased tip length36.

Determine the species list of lichens in the three poles

To create a comprehensive species list encompassing the majority of lichen species in the three polar regions, we conducted an extensive literature survey. The taxonomic focus was primarily at the species level, although subspecies, varieties, species sensu lato, aggregations, and hybrids were also considered. For simplicity, we collectively refer to them as ‘species’ unless a detailed distinction is deemed necessary. Our search strategy involved the use of keywords such as ‘lichen,’ ‘diversity,’ ‘lichenized fungi,’ ‘Arctic,’ ‘Antarctic,’ ‘Tibetan Plateau,’ and ‘polar region’ in prominent academic databases, including the Web of Science (https://webofscience.clarivate.cn/), Springer libraries (https://link.springer.com/), and Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (https://www.cnki.net/). This search yielded an extensive collection of results, totalling over 3,680 relevant sources (the key source articles are outlined in Table 3). Based on the information provided with these literatures we curated a list comprising 2803 lichen species in the three poles.

Assign values for the two attributes of lichen species on the list

For each of the identified species on the list, we conducted a thorough investigation by consulting various electronic databases, including the Consortium of Lichen Herbaria49, The Lichen Herbarium50, and Fungal Names51. Utilizing these diverse sources, we assigned the color type and growth form for each lichen species. Throughout this process, according to the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (ICN), we meticulously verified and standardized the species names of these lichens. To ensure the accuracy of attribute assignments, each assignment underwent a minimum of two checks.

Acquire spatial distribution data for lichen with different attribute values

To acquire distribution information supporting a geospatial analysis of patterns associated with different attribute values, we gathered observation records for all species on the list from the GBIF database52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144. Given the extensive nature of this process, we employed specialized crawling technology and utilized the ‘Taxon Key,’ ‘basis of record,’ ‘has coordinate,’ and ‘polygon range’ R functions to automatically filter the database. Observation records were downloaded for each species within the three polar regions. In the results, entries lacking geographic coordinates were excluded, and duplicate distribution records were eliminated. The final dataset comprises 170801 lichen records.

The color type and growth form values were assigned to these geographic lichen records based on the information of the corresponding species. For additional insights into their growing environment, we included ecoregion and biome details for each lichen record based on the RESOLVE Ecoregions 2017 dataset145, a well-established resource widely utilized in ecological studies146,147. The ArcGIS software was employed to determine the ecoregion and biome names of the lichen based on its coordinate location. Moreover, considering that more detailed information could provide additional insights, we incorporated the GBIF “occurrenceID” in the dataset, allowing detailed attributes—such other morphological characteristics of lichens—to be easily retrieved from the original record through the occurrenceID. Consequently, each record consists of information on scientific name, latitude, longitude, ecoregion name, biome name, growth form, color type, and occurrenceID in the GBIF database.

Data Records

The dataset is accessible on the Zenodo repository148. The data record is provided as a table file in xlsx format, featuring columns including “Index,” “Polar,” “Scientific name,” “Latitude,” “Longitude,” “Ecoregion name,” “Biome name,” “Growth form,” “Color type,” and “occurrenceID”. The implications and data types for each column are detailed in Table 4. A snapshot of sample records from the dataset is presented in Table 5. The dataset is released under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license, granting users the freedom to share, copy, and redistribute the material in any medium or format, as well as to adapt, remix, transform, and build upon it for any purpose.

In summary, after an exhaustive literature search, we focused on 2,803 lichen species found in the three pole regions. Color type and growth form for each species were carefully assigned based on their descriptions, experimental statistics, and photos. The presented dataset comprises 170801 in-situ measurements collected from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility Database149 for 2803 lichen species distributed across Earth’s three poles. Among these, 2208 species and 167218 observation records were documented in the Arctic, 433 species with 3468 observation records were found in the Antarctic, and 382 species with 115 observation records were located in the Tibetan Plateau. It is noteworthy that the abundance of records in the Arctic significantly surpasses that in the other polar regions. This difference can be attributed to various factors, including longer research histories, native languages of researchers, and data-sharing practices. While this imbalance may introduce potential bias in results derived from different polar regions, it should have a relatively minor impact on analyses of distribution patterns for different attribute values based on relative proportions. This is because the data-sharing tendencies of collectors are likely to be similar in a certain region.

Among the identified species, 14 lichens are present in all three polar regions: Cladonia carneola, Cladonia chlorophaea, Cladonia pleurota, Cladonia pocillum, Cladonia pyxidata, Cladonia scabriuscula, Cladonia squamosa, Lecanora intricata, Parmelia saxatilis, Physcia caesia, Physconia muscigena, Rhizocarpon geographicum, Rhizocarpon superficiale, and Xanthoria elegans. Notably, the Arctic and the Tibetan Plateau exhibit a higher degree of species overlap, with approximately 110 species distributed in both regions. Examples of these shared species include Acarospora schleicheri, Ahtiana pallidula, and Bryoria divergescens. Additionally, the Arctic and Antarctic share around 96 species, such as Alectoria sarmentosa, Cladonia bellidiflora, and Cladonia deformis. Excluding the six species present in all three poles, only one species, Umbilicaria thamnodes, was recorded in both Antarctic and the Tibetan Plateau. Further details can be found in Table 6.

Technical Validation

To validate the usability and credibility of our dataset, we performed statistical analyses and cross-referenced the results with data obtained through field investigations and established scientific knowledge.

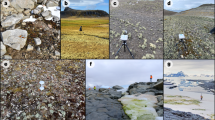

Firstly, we calculated the percentage of lichens with different attributes in each polar region, and the results are depicted in Fig. 2. Among the records in the dataset, dark lichens predominate in Antarctic (58.98%) and the Arctic (51.83%), while pale lichens are prevalent in the Tibetan Plateau (50.98%). The Antarctic region features virtually no green lichens but a significant presence of bright lichens (17.96%), in contrast to the Arctic (4.34%) and Tibetan Plateau (3.92%). The Arctic region boasts the highest proportion of green lichens among the three polar regions, albeit at a modest 8%. In contrast, the distribution of the three growth form types is relatively uniform and consistent across Earth’s three poles, with each growth form accounting for approximately 20% to 49%. These statistics are consistent with what we observed during our field investigation in Antarctic (January 2018, Ardley Island; February 2019, Great Wall Station), Arctic (July 2018, Ny-Alesund; July 2019, Yellow River Station), and Tibetan Plateau (August 2023, around the Ningchan River Glacier), which indicates the correctness of our dataset Fig. 3.

Lichens photos taken in the field investigation over the Earth’s three poles. (a) Pale, fruticose lichen in the Antarctic (58.955272°S 62.220753°W, January 14, 2018); (b) Dark, crustose lichen in the Arctic (78.158611°N 11.157056°E, July 15, 2018); (c) Crustose lichens of bright, pale, and dark color types on the Tibetan Plateau (37.527780°N 101.830143°E, August 18, 2023).

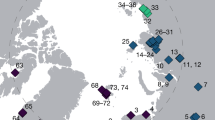

Secondly, we conducted a spatial analysis to examine the distribution patterns of different lichen attribute values through a relative comparison across various ecoregions. The results are presented in Fig. 4. Note that among the 70 ecoregions spanning Earth’s three poles, 14 ecoregions contain fewer than five lichen record. To prevent bias in the analysis, these ecoregions were excluded from subsequent assessments. From the results, a noticeable trend of increasing dark lichens with latitude is observed in both the Arctic and Antarctic, showing that the heat-absorbing property of dark lichen makes it possessing better adaptability in cold high latitude regions. However, this trend is not evident in the Tibetan Plateau, likely due to the complex topography and landforms in this region. Likewise, pale lichens exhibit a decreasing trend with latitude, comprising roughly one-quarter of the proportion in Northern high latitudes and becoming exceedingly rare in Southern high latitudes. Green lichens, possibly having low photoprotection ability, present in 25 out of 44 ecoregions in the Arctic. In contrast, they are found in only 5 out of 12 ecoregions in the Tibetan Plateau and a single ecoregion in Antarctic which are known with high-level of ultraviolet intensity150. Concerning growth forms, all three growth forms were documented in 24 out of 44 ecoregions in the Arctic. Notably, there is a higher prevalence of crustose lichens in high latitudes which has limited water and nutrition supply, and a greater occurrence of foliose lichens in low latitudes. Similarly, in Antarctic, fruticose lichens are primarily found in low latitudinal ecoregions. Like the case for the color type, the relationships between growth forms and geolocations are less clear due to the complicated topography in the Tibetan Plateau. The distribution pattern of these attributes can be well explained by heat regulation, photoprotection, and nutritional requirements, aligning with scientific common sense. This underscores the technical accuracy and effectiveness of our dataset.

Relative proportions of lichen color types and growth forms by ecoregion: (a) Arctic, (b) Antarctic, and (c) Tibetan Plateau. In each panel, concentric circles show growth forms in the inner circle and color types in the outer circle. Numbers represent ecoregion numbers from in the repository, with colors corresponding to biome regions in (d).

Usage Notes

This dataset can be used as a foundational resource for comprehensive investigations into the intricate interplay between lichen physiology and the growth environment, addressing a significant knowledge gap in the field. The inclusion of geospatial information allows for correlation analysis between the occurrence probability of different types of lichens, categorized by the two attributes, and various climate parameters. This analysis may contribute to uncovering climate thresholds for different lichens. Moreover, our dataset holds the potential to tackle challenges associated with remote sensing monitoring of lichens, a longstanding issue in vegetation remote sensing. Specifically, the color type defined and provided by our dataset is closely related to the spectral signature of lichens. This connection can facilitate the development of reflectance indices or spectral recognition methods for distinguishing various types of lichens.

Despite the richness of the dataset, it remains incomplete due to inherent challenges in data collection and organization, particularly the diversity of lichen species, the variability of regional habitats, and the absence of geographic coordinates for some records. While these challenges are unavoidable, they are not insurmountable. We plan to make regular updates and improvements to enhance the dataset’s completeness and accuracy. As data collection progresses, future versions will address these gaps and provide more detailed information on lichen distribution and traits. We are confident that these issues will be systematically resolved as the dataset evolves.

Data availability

The data and code are available at Zenodo148 (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8424701). The data needs to be run in the R (version 3.7) software.

References

Nash, T. H. (Eds.) Lichen Biology (Cambridge University Press, 2008).

Ahmadjian V. and Hale, M. E. (Eds.) The Lichens (Academic Press, 1973).

Honegger, R. Developmental biology of lichens. New Phytol. 125, 659–677 (1993).

Longton R. E. (Eds.) The biology of polar bryophytes and lichens (Cambridge University Press, 2008).

Li, Y. et al. Growth Rate of Usnea aurantiacoatra (Jacq.) Bory on Fildes Peninsula, Antarctica and Its Climatic Background. PLoS One. 9, e100735 (2014).

Sedov, S., Zazovskaya, E., Fedorov-Davydov, D. & Alekseeva, T. Soils of East Antarctic oasis: interplay of organisms and mineral components at microscale. Bol. Soc. Geol. Mex 71, 43–63 (2019).

Benítez, A., Aragón, G., González, Y. & Prieto, M. Functional traits of epiphytic lichens in response to forest disturbance and as predictors of total richness and diversity. Ecol Evol. 86, 18–26 (2018).

Coleine, C. et al. Rock Traits Drive Complex Microbial Communities at the Edge of Life. Astrobiology 23, 395–406 (2023).

Zhou, Y., Song, S. and Li, X. Biological crust profile and function of alpine forest and grassland ecosystems in Kangding City, China. Modern agricultural science and technology 18, 136–406 (in Chinese) (2022).

Alberto, A., Giuseppe, C., Luisa, M., Stefano, V., Luigi, P. D’ Acqui. Impact of biological crusts on soil formation in polar ecosystems, Geoderma, 401, 115340 (2021).

Markova, K. K., Bardin, V. I., Lebedev, V. C, Orlov, A. I., and Suetora, I. A. The Geography of Antarctica. (National Science Foundation, 1970).

Bliss, L. C. in North American and Scandinavian tundras and polar deserts, Tundra Ecosystems: a Comparative Analysis (ed. Bliss, L. C., Heal, O. W. & Moore, J. J.) Ch.1.2 (Cambridge University Press 1981).

Pickard, J. & Seppelt, R. D. Phytogeography of Antarctica. J Biogeogr. 11, 83–10 (1984).

Thomson, J. W. & Scotter, G. W. Lichens of the Great Slave Lake region, Northwest Territories, Canada. The Bryologist. 722, 137–177 (1969).

Thomson, J. W. & Scotter, G. W. Lichens from Bathurst Inlet region, northwest Territories, Canada. The Bryologist. 861, 14–22 (1983).

Thomson, J. W. & Scotter, G. W. Lichens of Bylot and Northern Baffin Islands, Northwest Territories, Canada. The Bryologist. 873, 228–232 (1985).

Thomson, J. W. & Scotter, G. W. Lichens of Eastern Axel Heiberg Island and the Fosheim Peninsula, Ellesmere Island, Northwest Territories. Canadian Field-Naturalist. 992, 179–215 (1985).

Thomson, J. W. & Scotter, G. W. Lichens of Cape Parry and Melville Hills regions, Northwest Territories. Canadian Field-Naturalist. 1061, 105–111 (1992).

Thomson, J. W. American Arctic Lichens, Volume 1: The Macrolichens. - Columbia University Press, New York. 504 (1984).

Thomson, J.W. American Arctic Lichens 2: The Microlichens. Univ of Wisconsin Press, Madison. 675 (1997).

Kristinsson, H., Hansen, E. S., and Zhurbenko, M. Pan-Arctic Checklist of Lichens and Lichenicolous Fungi. http://hdl.handle.net/11374/200 (2010).

Paulina, W., Michał, W. & Maja, L. Lichen Diversity on Glacier Moraines in Svalbard. Cryptogamie, Mycologie 38(1), 67–80 (2017).

Øvstedal, D.O., Lewis-Smith, R.I. Lichens of Antarctica and South Georgia. A Guide to their Identification and Ecology, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, ISBN 978-0-521-66241-3 (2001).

Sancho, L. G., Schulz, F., Schroeter, B. & Kappen, L. Bryophyte and lichen flora of South Bay (Livingston Island: South Shetland Islands, Antarctica). Nova Hedwigia. 68, 301–337 (1999).

Søchting, U., Øvstedal, D.O., Sancho, L.G. The lichens of Hurd Peninsula, Livingston Island, South Shetlands, Antarctica. In Contributions to Lichenology. Festschrift in Honour of Hannes Hertel, 1st ed.; Döbbeler, P., Rambold, G., Eds.; Bibliotheca Licheno-logica. J. Cramer in der Gebrüder Borntraeger: Berlin/Germany, Germany, 88, 607–658 (2004).

Wei, J. C., and Jiang Y. M. Lichens of Xizang. (Science Press, 1986). (in Chinese)

Wirth, V. Die Flechten Baden-Wu¨rtembergs. Verbreitungsatlas, Vols. I and II. (Eugen Ulmer, 1995).

Brodo, I. M., Sharnoff, S. D. and Sharnoff, S. Lichens of north America. (Yale University Press, 2001).

Rankovi, B. (Ed.) Lichen secondary metabolites: bioactive properties and pharmaceutical potential. (Springer, 2015).

Laguna-Defior, C., Pintado, A., Green, T. G. A., Blanquer, J. M. & Sancho, L. G. Distributional and ecophysiological study on the Antarctic lichens species pair Usnea antarctica/Usnea aurantiaco-atra. Polar Biol. 39, 1183–1195 (2016).

Phinney, N. H., Asplund, J. & Gauslaa, Y. The lichen cushion: A functional perspective of color and size of a dominant growth form on glacier forelands. Fungal Biology 126(5), 375–384 (2022).

Solhaug, K. A., and Gauslaa, Y. Secondary Lichen Compounds as Protection Against Excess Solar Radiation and Herbivores. (Springer, 2011).

Raven, P. H., Evert, R. F., and Eichorn, S. E. Biology of Plants. (New York Plz Ste, 2005).

Armstrong, R. & Bradwell, T. Growth of crustose lichens: a review. Physical Geography 92, 3–17 (2010).

Armstrong, R. & Bradwell, T. Growth of foliose lichens: a review. Symbiosis 53, 1–16 (2011).

Hale, M. E. The Lichens. (Academic Press, 1973).

Hale, M. E. The Biology of Lichens. (Edward Arnold, 1983).

Hurtado, P. et al. Disentangling functional trait variation and covariation in epiphytic lichens along a continent-wide latitudinal gradient. Proc. R. Soc. B. 287, 20192862 (2020).

Phinney, N. H., Ellis, C. J. & Asplund, J. Trait-based response of lichens to large-scale patterns of climate and forest availability in Norway. Journal of Biogeography 49(2), 286–298, https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.14297 (2021).

Ellis, C. J. et al. Functional Traits in Lichen Ecology: A Review of Challenge and Opportunity. Microorganisms 9(4), 766, https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9040766 (2021).

Benítez, A., Aragón, G., González, Y. & Prieto, M. Functional traits of epiphytic lichens in response to forest disturbance and as predictors of total richness and diversity. Ecological Indicators 86, 18–26, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2017.12.021 (2018).

Łubek, A., Kukwa, M., Jaroszewicz, B. & Czortek, P. Composition and Specialization of the Lichen Functional Traits in a Primeval Forest—Does Ecosystem Organization Level Matter? Forests 12(4), 485, https://doi.org/10.3390/f12040485 (2021).

Canali, G., Nuzzo, L. D., Benesperi, R., Nascimbene, J. & Giordani, P. Functional traits of non-vascular epiphytes influence fine scale thermal heterogeneity under contrasting microclimates: insights from sub-Mediterranean forests. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 205(1), 75–83, https://doi.org/10.1093/botlinnean/boad063 (2024).

López, L. G. C., Medina, E. A. S. & Peña, A. M. Effects of Microclimate on Species Diversity and Functional Traits of Corticolous Lichens in the Popayan Botanical Garden (Cauca, Colombia). Cryptogamie, Mycologie, 37(2), 205-215. https://doi.org/10.7872/crym/v37.iss2. 205. (2016).

Porada, P. et al. A research agenda for nonvascular photoautotrophs under climate change. New Phytologist 237(5), 1495–1504, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.18631 (2022).

Walshaw, C. V. et al. A satellite-derived baseline of photosynthetic life across Antarctica. Nature Geoscience 17(8), 755–762, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-024-01492-4 (2024).

Asplund, J. & Wardle, D. A. How lichens impact on terrestrial community and ecosystem properties. Biol. Rev. 92, 1720–1738 (2016).

Chen, J., Blume, H. P. & Beyer, L. Weathering of rocks induced by lichen colonization – a review. Catena. 39, 121–146 (2000).

The gateway to biodiversity data of lichenized fungi, The consortium of lichen herbaria https://lichenportal.org/portal/.

The Lichen Herbarium, https://nhm2.uio.no/lav/web/index.html.

Fungal Names, https://nmdc.cn/fungalnames/.

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.79f2xp (22 July 2021).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.ks8eec (22 July 2021).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.hzk2gc (29 June 2021).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.8wnd27 (10 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.xzs5br (10 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.w4a7eu (09 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.vmq83d (09 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.jbfd3q (09 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.cndcjf (09 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.686w76 (09 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.ytwzeq (09 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.8hnf6v (09 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.mvpnm9 (09 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.s39cbm (09 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.avyxxh (09 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.v9njrz (09 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.sjk7wj (09 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.fz66v4 (08 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.86fsfq (08 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.bq6rzc (08 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.n3fbyg (08 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.zx4tt7 (08 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.p5sypt (08 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.rjzhrs (08 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.exffrt (08 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.yvtugh (08 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.a6b56a (08 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.unjnsf (08 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.kv82u9 (08 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.992rpt (08 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.hbfkvf (08 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.9zrb6n (08 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.bscumv (08 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.gubt2c (08 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.2k24je (08 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.hhc7wy (08 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.mguau2 (03 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.yz768g (03 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.gfktqf (02 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.7gvpbt (02 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.8te7be (02 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.pz9bwa (02 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.uqck78 (02 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.y4wpsb (02 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.eh6ww9 (02 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.rm2b23 (02 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.buhrna (02 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.8na5p4 (02 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.ncn5tt (02 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.ycurvs (02 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.m454wt (02 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.p4vwdb (02 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.mx46nu (01 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.dvxbzs (01 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.fgjnmj (01 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.3tyjq9 (01 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.7bkr6c (01 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.d7v6nc (01 April 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.kuhv56 (30 March 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.yg3kug (30 March 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.t25p76 (30 March 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.yk9ray (30 March 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.2wsb39 (29 March 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.rwpwdf (29 March 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.hwauja (29 March 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.q9yu8e (29 March 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.tyrayk (29 March 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.z6zdgt (29 March 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.5q6qsu (29 March 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.uvhsx2 (29 March 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.n8rkuf (29 March 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.77xaq2 (29 March 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.unwgtm (29 March 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.acj7rp (29 March 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.qj6ajb (29 March 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.pkp4qx (29 March 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.wcy5p7 (29 March 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.ystg25 (29 March 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.cesfxp (29 March 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.ha4k6q (29 March 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.mj64cb (29 March 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.5bf9vg (29 March 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.wx3x55 (29 March 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.n7795f (29 March 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.zxsr6m (29 March 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.6ydzpv (29 March 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.4t6w78 (29 March 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.nfywa2 (29 March 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.hah7bg (29 March 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.4j3xh5 (26 March 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.vbw86w (22 March 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.u6pkap (22 March 2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.bs8tvd (22 March 2024).

Dinerstein, E. et al. An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm. BioScience 67, 534–545 (2017).

Rais, M. et al. Niche suitability and spatial distribution patterns of anurans in a unique Ecoregion mosaic of Northern Pakistan. PLoSOne 18, e0285867 (2023).

Martínez-Navarro, B. et al. The earliest Ethiopian wolf implications for the species evolution and its future survival. Commun Biol. 6, 530 (2023).

Alatan, Zhula., Wu, W. Z. & Li, X. W. Dataset of key attributes for lichens in the Earth’s three poles, Zenodo, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8424701 (2024).

Global Biodiversity Information Facility Database, https://www.gbif.org/.

Rose, F. Phytogeographical and ecological aspects of Lobarion communities in Europe. Bot J Linn Soc. 96, 69–79 (2008).

Geiser, L. H., Dillman, K. L., Derr, C. C. & Stensvold, M. C. Lichens of southeastern Alaska: an inventory. (USDA Forest Service, 1994).

Holt, E. A., McCune, B. & Neitlich, P. Defining a successional metric for lichen communities in the Arctic tundra. Arct Antarct Alp Res. 38, 373–377 (2006).

Printzen, C. Uncharted terrain: the phylogeography of arctic and boreal lichens. Plant Ecol Divers 1, 265–271 (2008).

Spribille, T. et al. Lichens and associated fungi from Glacier Bay National Park, Alaska. The Lichenologist 52(2), 61–181 (2020).

Flora of Island, http://www.floraislands.is/index.html.

Mapping of Norwegian lecideoid lichens, https://nhm2.uio.no/botanisk/lav/LAVFLORA/LECIDEOID.HTM.

Zahlbruckner, A. Catalogus Lichenum Universalis 5 (Leipzig, 1928).

Zahlbruckner, A. Lichens in H. Handel-Mazzetti (Symbolae Sinicae, 1930).

Zahlbruckner, A. Catalogus Lichenum Universalis 8 (Leipzig, 1932a).

Zahlbruckner, A. Lichens (Feddes Repertorium, 1932b).

Zahlbruckner, A. Flechten der Insel Formosa (Feddes Repertorium, 1933).

Zahlbruckner, A. Nachträge zur Flechtenflora Chinas (Hedwigia, 1934).

Makarevicz, M. F. Handbook of the lichens of the USSR 1 Pertusariaceae, Lecanoraceae and Parmeliaceae (Kopaczevskaja, 1971).

Poelt, J. Die lobaten Arten der Sammelgattung Lecanora. Lichenes, Lecanoraceae. (Flechten des Himalaya 1), in: Khumbu Himal Ergebn. Forsch.-Unternehmens Nepal Himalaya, edited by: Hellmich, W., Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. 187–202 (1966).

Wei, J. C. and Chen J. B. Lichen floristic data of Qomolangma area in: Report of scientific investigation in Qomolangma region (ed. Wei, J. C. and Chen, J. B.) (in Chinese) (Science Press, 1974).

Wei, J. C. An overview of lichens in China (in Chinese) (Wanguo academic Press, 1991).

Obermayer, W. Additions to the lichen flora of the Tibetan region in Contributions to Lichenology (ed. Döbbeler, P. & Rambold, G.) (Gebrüder Borntraeger Verlagsbuchhandlung, 2004).

Zhao, Z. T., Qiang, R. & Aptroot, A. An annotated key to the lichen genus Pertusaria in China. Bryologist. 107, 531–541 (2004).

Baniya, C. B., Solhøy, T., Gauslaa, Y. & Palmer, M. W. Richness and Composition of Vascular Plants and Cryptogams along a High Elevational Gradient on Buddha Mountain. Central Tibet Folia Geobot. 47, 135–151 (2012).

Huang, M. R. & Guo, W. Altitudinal gradients of lichen species richness in Tibet, China. Plant Divers. 34, 192–198 (2012).

Timdal, E., Obermayer, W. & Bendiksby, M. Psora altotibetica (Psoraceae, Lecanorales), a new lichen species from the Tibetan part of the Himalayas. MycoKeys. 13, 35–48 (2016).

Wei, J. C., and Jiang, Y. M. Lichen of Tibet (in Chinese) (Science Press, 1986).

Nakanishi, S. Ecological studies of the moss and lichen communities in the ice-free areas near syowa station, Antarctica. Antarctic Record 59, 68–96 (1997).

Kappen, L. & Redon, J. Photosynthesis and water relations of three maritime Antarctic lichen species. Flora 179, 215–229 (1987).

Li, X. D. An overview of vegetation near China’s Great Wall Station in Antarctica. Plant journal 19, 45–46, (in Chinese) (1992).

Li. X. M., Zhao, J. L., and Sun, L. G. Nourishing characteristic of geochemical elements in Antarctic mosses and lichens. Chin J Appl Ecol. 4, 513-516 (in Chinese) (2001).

Yin, X. B., Sun, L. G., and Pan, C.P. Characterization of the bioconcentration of HCH, DDT in the plant-soil system of the Antarctic tundra. Progress in natural sciences 7, 103-106 (in Chinese) (2004).

Kim, J. H. et al. Lichen Flora around the Korean Antarctic Scientific Station, King George Island, Antarctic. J Microbiol. 44, 480–491 (2006).

Seymour, F. A. et al. Phylogenetic and morphological analysis of Antarctic lichen forming Usnea species in the group Neuropogon. Arctic Science 19, 71–82 (2007).

Han, L. L., and Wei, J. C. A preliminary study on the antioxidant activity of Antarctic Lichen extract. Mycosystema 28, 846–849 (in Chinese) (2009).

Seppelt, R. D. et al. Lichen and moss communities of Botany Bay, Granite Harbour, Ross Sea, Antarctica. Antarctic science 22, 691–702 (2010).

Casanovas, P., Lynch, H. J., Fagan, W. F. & Naveen, R. Understanding lichen diversity on the Antarctic peninsula using parataxonomic units as a surrogate for species richness. Ecology 94, 2110 (2013).

Peat, H. J., Clarke, A. & Convey, P. Diversity and biogeography of the Antarctic flora. Journal of Biogeography 34, 132–146 (2007).

Olech, M. Lichens of King George Island, Antarctica, 1st ed.; Institute of Botany of Jagiellonian University: Kraków, Poland, ISBN 978-83-915161-7-1 (2004).

Pertierra et al. TerrANTALife 1.0 Biodiversity data checklist of known Antarctic terrestrial and freshwater life forms. Biodiversity Data Journal 12, e106199 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The research was co-funded by the National Science Foundation of China (42276241) and the International Joint Research Project of Chinese Academy of Sciences (183611KYSB20200059). We would like to thank GBIF for sharing the massive species occurrence data that provided the basis for the establishment of our dataset.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W. Wu and H. Guo conceived the ideas; Alatanzhula collected sources, processed the data, and performed the analysis; C. Hao, J. Li, Alatanzhula, and X. Li conducted the field investigation. Alatanzhula and W. Wu wrote the paper; X. Li and L. Zhao reviewed the paper and contributed substantially to revisions.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alatan, Z., Wu, W., Li, X. et al. A geospatial dataset of lichen key attributes in the Earth’s three poles. Sci Data 11, 1248 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-04072-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-04072-8