Abstract

Solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence (SIF) serves as a valuable proxy for photosynthesis. The TROPOspheric Monitoring Instrument (TROPOMI) aboard the Copernicus Sentinel-5P mission offers nearly global coverage with a fine spectral resolution for reliable SIF retrieval. However, the present satellite-derived SIF datasets are accessible only at coarse spatial resolutions, constraining its applications at fine scales. Here, we utilized a weighted stacking algorithm to generate a high spatial resolution SIF dataset (500 m, 8-day) in China (HCSIF) from 2000 to 2022 from the TROPOMI with a spatial resolution at a nadir of 3.5 km by 5.6–7 km. Our algorithm demonstrated high accuracy on validation datasets (R2 = 0.87, RMSE = 0.057 mW/m2/nm/sr). The HCSIF dataset was evaluated against OCO-2 SIF, GOME-2 SIF tower-based measurements of SIF, and gross primary productivity (GPP) from flux towers. We expect this dataset can potentially advance the understanding of fine-scale terrestrial ecological processes, allowing for monitoring of ecosystem biodiversity and precise assessment of crop health, productivity, and stress levels in the long term.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

The recent IPCC report emphasizes the importance of terrestrial ecosystems in mitigating atmospheric CO2 concentration increase and global climate warming through photosynthesis and carbon cycling1. Terrestrial ecosystems in China are essential for global carbon sequestration, in the next 40 years (2021–2060), the carbon sink potential of China’s terrestrial ecosystems is estimated to be 297 to 360 million t C/a2,3,4. Spatially and temporally high-resolution measurements of terrestrial vegetation photosynthesis are essential for providing insights into variations within ecosystems and landscapes5,6,7,8. In recent decades, solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence (SIF) has been acclaimed as a proxy for vegetation photosynthesis9. Advancements in remote sensing of SIF have unveiled the authentic physiological status of vegetation10,11,12,13, offering possibilities for large-scale vegetation photosynthesis monitoring.

SIF is a spectral emission resulting from photosynthetic activity, produced by excited chlorophyll-a molecules in the photosystem reaction centers within the 650 to 800 nm spectral range14. It is closely associated with the electron transfer rate in the light reaction15. Existing satellites, which were originally designed for atmospheric composition monitoring, such as the Greenhouse Gases Observing Satellite (GOSAT)16. Global Ozone Monitoring Experimental-2 (GOME-2)17, Environmental Satellite (ENVISAT)18, Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 (OCO-2)10, and Orbiting Carbon Observatory-3 (OCO-3)19, were repurposed to retrieve surface SIF products15. The global ozone monitoring satellites GOSAT/GOSAT-2, GOME/GOME-2, and ENVISAT offer advantages of global coverage of SIF with short revisit cycles, albeit at low spatial resolutions, typically at 0.5° or 1° grid resolutions. GOME-2 satellites provide long-term observations, although their sensors may degrade over time12,20. While the OCO-2/OCO-3 series offer high spatial resolutions (at nadir: 1.3 km × 2.25 km and 1.6 km × 2.2 km), large spatial gaps in their imagery limit further applications10,21. Overall, the TROPOspheric Monitoring Instrument (TROPOMI) provides a relatively high spatial resolution (at nadir: 5.5 × 3.5 km) with nearly global coverage, but the datasets are only available from 2018 onward. Additionally, satellite-derived SIF datasets are sensitive to imaging conditions such as clouds and fog cover, leading to insufficient observations within grid cells (~10 km) and resulting uncertainties. Therefore, obtaining high-quality, high-resolution, long-term, and continuous SIF data remains a crucial challenge in current large-scale vegetation photosynthesis research, with significant scientific and practical implications22,23.

To address concerns such as temporal and spatial discontinuity and insufficient spatial resolutions of SIF products, recent efforts have focused on improving the spatiotemporal resolution of current SIF retrievals through a series of downscaling methods, including machine learning-based and physics-based approaches24,25,26,27,28. Compared to physics-based approaches, machine learning-based approaches can consider more variables and better represent the nonlinear relationship between variables and SIF22,24. Most SIF downscaling studies have focused on extending temporal scales. Hu et al.29 used photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) data and vegetation indices to extend GOME-2 SIF estimates from clear sky observations to include all-sky conditions (8-day, 0.5°). Chen et al.27 used MODIS land surface temperature (LST), spectral reflectance (SR), PAR data and used the extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost) algorithm to reconstruct TROPOMI SIF during the 2001–2020 period under clear-sky conditions (8-day, 0.05°). However, these publicly available datasets exhibit coarse spatial resolutions. Gensheimer et al.24 utilized a convolutional neural network to simulate TROPOMI SIF to 500 m over the conterminous United States (CONUS). Kang et al.30 used SR and fraction of PAR (fPAR) data and employed Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) to simulate OCO-2 SIF from a resolution of 0.05° to 0.0005° (≈50 m) in Northern Xinjiang in China to estimate cotton yield. Compared with neural network algorithms (e.g. CNN), tree-based models (e.g. random forest, RF) offer the advantages of swift training speeds and straightforward parameter tuning31,32. Jin et al.33 utilized the RF algorithm and integrated GOME-2 SIF and Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) SR data, fPAR, European Reanalysis (ERA5) data, to simulate SIF at a resolution of 0.05° in East China from 1995 to 2003. From the perspective of modeling variables, existing research mainly relies on vegetation indices calculated from SR, LST, fPAR and meteorological data to perform SIF downscaling. The capacity of vegetation photosynthesis to respond non-linearly to environmental conditions is influenced by topography, and thus leads to SIF variations34,35, but existing studies lack sufficient consideration of topography-related factors (e.g. elevation, slope, aspect). Considering downscaling methods, a single machine learning algorithm has limitations in fitting capability, and the stacking ensemble algorithm can overcome the limitations of individual machine learning algorithms, offering better fitting capability and stability36,37. Existing long-term SIF downscaling datasets (Table 1), suffer from coarse spatial resolutions, and long-term, high-spatial resolution SIF products (e.g, 500 m) are currently limited for many regions including China, restricting their utility for photosynthesis monitoring and carbon cycle estimation27.

Therefore, this study aims to use a weighted stacking ensemble algorithm for downscaling TROPOMI SIF over an extended period (2000–2022) in 8-day intervals at 500 m resolution over China (HCSIF), a homebase for the largest number of smallholders (230 million) with less than 2-hectare landholdings. HCSIF is derived from Caltech TROPOMI SIF data 11, Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) vegetation indices38,39, fPAR data40, digital elevation model (DEM) data41, and ERA5-Land data42. The three objectives of the study were to (1) develop a stacking-based downscaling model coupled with topography-related variables; to (2) produce a long term, high-resolution SIF dataset (HCSIF) for China; and to (3) evaluate the resulting HCSIF with tower-based measurements of SIF, gross primary productivity (GPP) from flux towers, OCO-2 SIF, and GOME-2 SIF respectively. We anticipate this novel dataset has the potential on monitoring ecological processes, the carbon cycle, and assessing the effects of climatic variability on agriculture and forestry at fine scales.

Methods

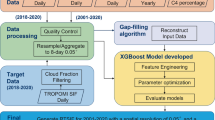

Framework overview

Figure 1 depicts the overall framework for generating HCSIF. According to Zhang et al.43, SIF can be represented based on the light-use-efficiency (LUE) concept as follows:

where APAR is the absorbed PAR, \({f}_{{esc}}\) is the escape probability of fluorescence (the probability of SIF escaping from the photosystem to the canopy, FE is the fluorescence efficiency observed at the top of the canopy (the proportion of absorbed PAR photons that are re-emitted as SIF photons from the canopy)44,45. \({S}_{0}\) is sun constant (1367 W/m2), \(\alpha \) is the proportion of solar irradiance within 400–700 nm range, DOY is the day of year46 (Table S1 and Table S2 in Supporting Information presents an explanation of the symbols and abbreviations used in this study). PAR can be approximated by the product of the cos (SZA) and the solar constant under clear sky conditions44. Previous studies have shown that spectral reflectance and fPAR are widely used to construct SIF models24,47. In this study, the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI)48, the normalized difference water index (NDWI)49, the near-infrared vegetation index (NIRv)50, and the nonlinear vegetation index kernel NDVI (kNDVI)51 were calculated from spectral reflectance data. LST can be used as a proxy for thermal stress when constructing a SIF model52. Previous studies have shown high correlations between SIF and meteorological data, while soil moisture (SM) and vapor pressure deficit (VPD) were selected to construct a downscaling model53. The influence of topography on the non-linear relationship between environmental factors and vegetation photosynthesis leads to fluctuations in SIF34,35. Considering the crucial role of mountainous regions in climate change, topography-related features were selected for this downscaling model. Thus, we selected multiple features such as spectral reflectance (SR), land surface temperature (LST), fPAR, meteorological factors, and topography to construct the downscaling model. Given the structural and physiological variations among different biomes, we hypothesize that incorporating biome type may enhance the estimation accuracy of the SIF model. We finally selected13 features including the NDVI, NIRv, NDWI, kNDVI, LST day, LST night, the cosine of solar zenith angle [cos (SZA)], FPAR, VPD, SM, slope, aspect and elevation as input variables for HCSIF modeling.

Input datasets

The HCSIF was created based on multiple datasets. Table 2 provides an overview of all the datasets that were used.

For model training and evaluation, we utilized Caltech TROPOMI SIF data from March to October (the growing season) spanning 2018 to 202211. We focused on daily average clear-sky SIF data with cloud fractions below 0.2 and excluded data with a SZA exceeding 70°. The ungridded data were then aggregated into 0.2° grids at an 8-day interval, aligning closely with the TROPOMI SIF footprint size. We specifically employed SIF values at 740 nm from the 743–758 nm retrieval window, which offers optimal retrieval precision and minimal cloud sensitivity54.

Ancillary input data comprising MODIS products38,39, ERA5-Land products42, and Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) DEM products41 were used to generate HCSIF. We chose MODIS data from the NASA Terra satellite for SIF downscaling due to their high temporal resolution (8-day). The MODIS products chosen were MOD09A1 (SR)55, MOD11A2 (LST)38, MOD15A2H (fPAR)40, MOD09GA (SZA)56 and MCD12Q1 (land cover) products39 (Table 2). To analyze the SIF downscaling accuracy for the different vegetation types, we used an updated MCD12Q1 for each year. The MOD09GA data were used as a proxy for SIF modeling and were averaged over an 8-day period. To minimize uncertainty in the SIF estimation, only MOD09A1 and MOD11A2 of high quality (cloud fractions less than 0.2) were used. To addressed and corrected observations impacted by poor atmospheric conditions, the 8-day MOD09A1 and MOD11A2 data were reconstructed using gap-filling and smoothing methods. Bilinear interpolation was used to interpolate all products to a resolution of 0.2°. The MCD12Q1 products were based on the International Geosphere Biosphere Programme (IGBP) classification scheme, which includes 17 land cover types. We consolidated these 17 types into five classes following the strategy of Zhang et al.57., i.e., deciduous broadleaf forest (DBF) and mixed forest were grouped as DBF, woody savannas and savannas (SAV) were grouped as SAV, and croplands (CRO) and cropland/natural vegetation mosaics were grouped as CRO. These five vegetation types comprised evergreen broadleaf forest (EBF), DBF, SAV, grassland (GRA) and CRO (Fig. S1 in the Supporting Information). Vegetation indices such as NDWI, NDVI, NIRv, and kNDVI were derived from MOD09A1 products by combining the red, near-infrared, and shortwave-infrared bands.

The ERA5-Land dataset offers weather variables at an hourly resolution and a spatial resolution of 0.1°, covering the period from 1950 to the present42. The meteorological variables involved in SIF downscaling include soil moisture (SM), vapor pressure deficit (VPD). VPD was computed based on dewpoint temperature (DTa) and air temperature (Ta) according to the formula proposed by Yuan et al.58. The SM data were calculated for the 0–100 cm soil layer using the weighted algorithm. The SM and VPD datasets were aggregated to the 8-day scale using the average aggregated algorithm at 0.2° resolution for model construction, and then resampled to 500 m using bilinear interpolation for SIF estimation.

The 30 m resolution DEM data downloaded from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) were adopted for model training41. The aspect and slope data were extracted using the ArcGIS 10.7. The aspect, slope, and DEM data were resampled to 0.2° and 500 m resolution using the bilinear interpolation for SIF model construction.

Model configurations

Tree-based models offer the advantages of swift training speeds and straightforward parameter tuning31,32. However, individual machine learning algorithms are often constrained by estimation accuracy and generalizability. Therefore, this study employs the weighted Stacking ensemble algorithm, which integrates three tree-based algorithms: two typical Boosting algorithms (Category boosting, CatBoost and gradient boosting decision tree, GBDT), and a typical Bagging algorithm (Random forest, RF) as the base learners. The weight of each base learner is determined by prediction error, thereby enhancing model accuracy59. Additionally, to reduce the risk of overfitting, a linear model is employed as the secondary learner60. This approach leverages the unique strengths of each of these three machine learning algorithms.

CatBoost represents an innovative gradient boosting technology inspired by the XGBoost and LightGBM algorithms. Notably, it adeptly manages categorical features through a greedy approach. To address gradient biases, the algorithm employs ordered boosting61,62,63. RF incorporates Breiman’s “bagging” concept, integrating multiple decision tree classifiers to form a robust model. It achieves this by training numerous decision trees and determining the class corresponding to the mode or mean forecast of each tree64. GBDT, a well-established Boosting algorithm, combines multiple regression tree models to craft a resilient learner65. Additionally, to counteract overfitting, linear regression served as the secondary learner60 in constructing the SIF downscaling model. Furthermore, adjustments to the weights of the basic learners were made based on their estimation errors to enhance the overall model accuracy.

In this study, we simulated the SIF during the growing season (March to October) from 2000–2022. The weighted-stacking model was constructed in two ways: jointly across all biomes (referred to as the universal model) and individually for each biome (referred to as the biome-specific model). Before the training process, each variable was standardized using its deviation and mean. The training dataset and the test dataset were split at a ratio of 7:3. To reduce the dimensionality of the feature space, improve computational efficiency, and mitigate the risk of overfitting, we used the feature importance output by each tree model to inform feature selection66. The “SelectFromModel” method from the sklearn library is employed to determine the most advantageous subset of features67, with selection based on setting the threshold at the median. Thirteen features serve as independent variables, while SIF is used as the dependent variable in the weighted-stacking ensemble learning model. Initially, training and feature selection are conducted based on three tree-based models (CatBoost, RF, GBDT), which operate independently and generate predictions based on the input features. Subsequently, the prediction results are fed into the linear model for secondary training and estimation (Fig. 2). Many hyperparameters in the base learners affect the model performance, and the Bayesian optimization (BO) algorithm was selected to determine the optimal combination of parameters because it requires fewer iterations and has a faster processing speed68.

Ground-based validation datasets

Long-term and continuous tower-based SIF and GPP observations can provide ideal and accurate test datasets for the validation of the SIF downscaling method. In this study, we firstly collected data from three tower sites capable of providing spectrum measurements for SIF retrieval69, situated in Shangqiu (34.587 N, 115.5753E), Henan, China and Jurong (31.8068 N, 119.2173E), Jiangsu, China, and Xilinhot (43.5513 N,116.6710E), Inner Mongolia, China (https://chinaspec.nju.edu.cn/). Besides, we also downloaded four tower-based SIF validation datasets (Arou, Daman, Gucheng, Huailai) from literature69,70. To further validate our HCSIF results, GPP observations measured at the three eddy covariance (EC) flux towers (Shangqiu, Jurong, Xilinhot) were used. Furthermore, we downloaded four flux towers measurements (Damao, Ruoergai, Huzhong, Maoershan) from the China Flux Observation and Research Network71 (ChinaFLUX) (http://www.chinaflux.org/index.aspx). Detailed information on all the sites for SIF and GPP measurements is listed in Table 3 and Table 4.

The daily correction factor was used to convert the TROPOMI instantaneous SIF values into daily averages. To achieve temporal matching between simulated HCSIF (8-day) and \({{\rm{SIF}}}_{{in} \mbox{-} {situ}}\) (hourly),the average method was used to aggregate the \({{\rm{SIF}}}_{{in} \mbox{-} {situ}}\) to an 8-day resolution. Furthermore, the spatial scale difference between the HCSIF (500 m) and tower-based in situ SIF measurements (1–10 m) was considered. Due to the availability of the data, the in-situ NIRv data were used for the Jurong and XLHT site, while the Sentinel-2 NIRv data centered at the location of tower were used for the other sites72. To match the footprint size of the original TROPOMI pixels, NIRv were employed to connect tower-based SIF with the corresponding TROPOMI SIF samples70, the calculation formula is as follows:

where \({{\rm{SIF}}}_{{in} \mbox{-} {situNIRv}}\) is the NIRv-scaled tower-based SIF value, \({{NIRv}}_{{TROPOMI}}\) denotes the NIRv value corresponding to each matched original TROPOMI sample, which is computed using the MODIS reflectance data, and \({{NIRv}}_{{in} \mbox{-} {situ}}\) denotes the NIRv value at the site scale. \({{\rm{SIF}}}_{{in} \mbox{-} {situ}}\) represents the matched tower-based SIF sample.

Satellite-based validation datasets

To validate the downscaled HCSIF products, we selected OCO-2 SIF, GOME-2 SIF and the original TROPOMI SIF for comparison. OCO-2 SIF retrievals at 757 nm and 771 nm were converted to 740 nm using a wavelength factor of 0.75, and then a correction factor was used to generate daily corrected SIF at 740 nm. We aggregated all clear-sky, high-quality SIF data from OCO-2 (2015–2021), GOME-2 (2007–2017) and original TROPOMI data to a 0.2° grid with an 8-day resolution.

We further compared HCSIF with GPP products generated by He et al.73,74. This dataset provides GPP estimates at 500 m resolution across China. We used GPP products (2018–2020) and aggregated the products to an 8-day temporal resolution.

Data Records

Our long-term high spatiotemporal SIF dataset, HCSIF, is available at https://www.scidb.cn/en/detail?dataSetId=2498ad34919e43a79c9443f58e863f4275. The data record includes China HCSIF data from March to October (the growing season) over the 2000–2022 period at 8-day/500 m resolution. There are 30 GeoTiff files for each year, with each file corresponding to each 8-day period. The unit is mW/m2/nm/sr. The filename SIF < YYYY > - < DDD > .tif offers details on the year and the start date of the 8-day period. Additionally, we provide a NetCDF file for each year, encompassing the 30 time series of HCSIF corresponding to that year, formatted as SIF < YYYY > .

Technical Validation

Model validation

To assess the benefits of the proposed weighted-stacking ensemble model in terms of downscaling accuracy, we tested its performance and compared it with each individual machine learning algorithm. For physically based downscaling, and such comparisons are not meaningful because the scaled value is forced to agree with the input data for each coarse pixel, but machine learning methods are trained for the whole region, and such comparisons become meaningful. Figure 3 indicates that, the weighted-stacking ensemble algorithm achieved the highest coefficient of determination (R²) value of 0.88, outperforming CatBoost (0.86), RF (0.77), and GBDT (0.86). Correspondingly, the root mean square error (RMSE) was lowest for the weighted-stacking algorithm at 0.057 mW/m²/nm/sr, outperforming CatBoost (0.060 mW/m²/nm/sr), RF (0.077 mW/m²/nm/sr), and GBDT (0.060 mW/m²/nm/sr). In addition, the bias was lowest for the weighted-stacking algorithm (0.0010 mW/m2/nm/sr), lower than that of stacking (0.037 mW/m2/nm/sr), CatBoost (0.0018 mW/m2/nm/sr). RF (0.0032 mW/m2/nm/sr), and GBDT (0.0022 mW/m2/nm/sr). These results indicate that the model built based on the weighted-stacking ensemble algorithm achieved the best accuracy.

To further demonstrate the effectiveness of the chosen topography-related features (DEM, aspect, slope), SIF downscaling models using various features were constructed using the weighted-stacking algorithm. Figure 4 indicates that, compared with the model without considering topographical variables, the model with integrated topography showed improvement. The R2 improved from 0.85 mW/m2/nm/sr to 0.88 mW/m2/nm/sr, the RMSE value reduced from 0.062 mW/m2/nm/sr to 0.057 mW/m2/nm/sr, and the bias decreased from 0.0027 mW/m2/nm/sr to 0.0010 mW/m2/nm/sr.

Test results of the downscaling models based on different features. The color bar shows the density of the scatter plot using kernel density estimation (KDE). (a) Downscaling accuracy of the model used all features excluded topography-related features. (b) Downscaling accuracy of the model used all features.

Comparison between model configurations

We evaluated the ability of the universal and biome-specific models to simulate TROPOMI SIF for 5 different biomes (Fig. 5). The universal model achieved better accuracy than the biome-specific models for DBF, EBF, and SAV. The biome-specific model showed better accuracy than universal model for CRO and GRA. In conclusion, the universal model showed fine applicability to different vegetation types, the R2 of the universal model was higher than 0.6 for DBF, SAV, and GRA. The universal model showed the highest accuracy for DBF, which is 0.83. The ΔSIF for 5 major biome types was computed with both the biome-specific and universal models (Fig. 6). The biome-specific model showed an overestimation for DBF (0.01 mW/m²/nm/sr) and EBF (0.01 mW/m2/nm/sr). However, the biome-specific model showed an underestimate for SAV (0.02 mW/m2/nm/sr). This resulted from variations in the terms of escape probability of fluorescence (fesc, the probability of SIF escaping from the photosystem into the canopy) and clumping index (CI) between crops and forests. Due to the high clumping and structural complexity, forests allow less fluorescence to escape the canopy57. Despite CRO and GRA having high fesc and CI, no underestimations were shown for the predicted SIF for CRO and GRA using the biome-specific model. The universal model showed an overestimation for both DBF (0.01 mW/m2/nm/sr) and EBF (0.01 mW/m2/nm/sr). The universal model demonstrated a lower bias than the biome-specific model for SAV (0.01 mW/m2/nm/sr) but a higher bias for GRA (0.04 mW/m2/nm/sr). No underestimation was observed for predicted SIF using the universal model for GRA. The universal model showed approximate biases with the biome-specific model in the range of 0 to 0.05 mW/m2/nm/sr. For simplicity, the universal model was used to simulate SIF.

The accuracy of universal and biome-specific models of different vegetation types. (a) biome-specific (DBF). (b) universal (DBF). (c) biome-specific (EBF). (d) universal (EBF). (e) biome-specific (SAV). (f) universal (SAV). (g) biome-specific (CRO). (h) universal (CRO). (i) biome-specific (GRA). (j) universal (GRA).

Validation against ground-based SIF

The in-situ SIF continuous measurements were first used to validate the HCSIF accuracy (Fig. 7). To transform the tower-based SIF760 measurements to SIF740, a ratio of 1.48 was ultimately applied according to the slope value of the statistical relationship. Considering the spatial scale difference between the simulated HCSIF (500 m) and tower-based in situ measurements (1–10 m), NIRv data were used to align tower-based SIF measurements with HCSIF samples to match the HCSIF pixel size70. The results showed the correlation coefficient (r) between the site SIF and simulated HCSIF at 8-day intervals. DM showed the highest r value, reaching 0.76. GC came next, reaching above 0.7. Most site values of absolute r were above 0.5. The error was possibly due to landscape heterogeneity. The results demonstrate fine consistency between the simulated HCSIF and tower-based SIF.

Correlation between the tower-based SIF measurements and simulated HCSIF. (a) In-situ SIF and HCSIF in the AR from April to October during the years 2019 to 2021; (b) In-situ SIF and HCSIF at DM from May to October 2020; (c) In-situ SIF and HCSIF at GC from May to October during the years 2018 to 2021; (d) In-situ SIF and HCSIF at HL from July to October 2019; (e) In-situ SIF and HCSIF at XLHT from May to September 2019; and (f) In-situ SIF and HCSIF at JR from May to September 2019. The color bar shows the density of the scatter plot using KDE.

Validation against ChinaFLUX measurements

To validate the accuracy of the HCSIF and assess its significant role in monitoring and understanding the dynamics of ecosystem photosynthesis76, we used the tower GPP using data collected from 6 ChinaFLUX sites (Table 4) for comparative analysis. The tower GPP estimates were aggregated to an 8-day resolution.

Our analysis revealed a clear linear relationship between HCSIF and GPP, indicating a significant correlation between the two (Fig. 8). Based on the verification results, the agreement between HCSIF and GPP was generally strong at the 8-day scale; in particular, the r value surpassed 0.7 for three sites: MES, HZ, and XLHT. MES exhibited the strongest correlation (r = 0.75), followed closely by HZ with r = 0.74. All sites displayed correlation coefficients exceeding 0.5.

Correlation between the GPP and simulated HCSIF. (a) Measured GPP and HCSIF at SQ from May to September 2020; (b) Measured GPP and HCSIF at XLHT from May to September 2019; (c) Measured GPP and HCSIF at DM2 from May to September during 2015 to 2018; (d) Measured GPP and HCSIF at REG from March to October during 2015 to 2020; (e) Measured GPP and HCSIF at HZ from March to October during 2014 to 2018; and (f) Measured GPP and HCSIF at MES from March to October during 2015 to 2018.

Validation against other spaceborne SIF

The HCSIF dataset was compared with the original TROPOMI SIF, OCO-2 SIF, and GOME-2 SIF10. Figure 9 indicates that, at the countrywide scale, HCSIF demonstrates fine agreement with the original TROPOMI SIF and OCO-2 SIF with r > 0.7 and a regression slope close to 1. The HCSIF shows high accuracy with the original SIF in the eastern part of China, including the Northeast Plain and North China Plain regions. However, as r decreases, the regression slope becomes lower or even negative in the northwestern Inner Mongolia Plateau and the southern Yun-Gui Plateau region. This is mainly due to the northwestern plateau area being located in the temperate desert area. Where the sparse vegetation, significant soil background interference and lower levels of photosynthetic activity led to certain errors in the estimation77,78. The southern Yun-Gui Plateau region is situated in the tropical rainforest region, characterized by significant altitude variations and diverse vegetation types. Limited availability of effective remote sensing data due to frequent rainfall events may have introduced noise into the observational data and affected the estimation of SIF79. Compared to the original TROPOMI SIF, OCO-2 SIF has a higher spatial resolution (1.3 km × 2.25 km) but exhibits large spatial gaps. HCSIF demonstrates strong agreement with OCO-2 SIF and effectively addresses the spatial and temporal gaps where OCO-2 SIF data are discontinuous. The results reveal a strong correlation between HCSIF and GOME-2 SIF, with a similar distribution pattern in both r and slope when compared to OCO-2 SIF. However, the r between HCSIF and GOME-2 SIF is low, likely attributable to the large footprint of the GOME-2 satellite (40 km x 80 km or 40 km x 40 km), which may increase susceptibility to cloud contamination in subpixels, resulting in an underestimation of SIF values80. Overall, compared with the original TROPOMI SIF, OCO-2 SIF and GOME-2 SIF products, HCSIF offers reliable and spatially continuous estimates of SIF.

Figure 10 shows the distributions of HCSIF, the original TROPOMI SIF in regions characterized by diverse terrains. The results indicate that the spatial distribution of HCSIF is generally consistent with the original TROPOMI SIF. Notably, the initial TROPOMI SIF does not have insufficient spatial details to capture intricate nuances. In contrast, HCSIF is more adept at characterizing fine-scale features than TROPOMI SIF. This result is consistent with the features of NIRv across the Yellow-Huaihe-Haihe River Plain, the Sichuan Basin, the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau, and the Middle–Lower Yangtze Plain. Moreover, HCSIF successfully fills the spatial gaps in the initial TROPOMI SIF across various regions, such as the Yellow-Huaihe-Haihe River Plain, the Sichuan Basin, the Northern arid and semi-arid region, and the Northeast Plain. The scatter plots indicate that HCSIF shows strong consistency with original TROPOMI SIF. Overall, HCSIF demonstrates its capacity to offer enhanced details, which can significantly benefit various applications.

Comparison of HCSIF, original TROPOMI SIF, NIRv and the scatter comparison between the HCSIF and TROPOMI SIF estimated at 0.2°; the white area denotes the invalid data. (a–d) The Yellow-Huaihe-Haihe River Plain, (e–h) The Sichuan Basin, (i–l) The Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau, (m–p) and the Middle–Lower Yangtze Plain.

Comparison against GPP products

Furthermore, HCSIF was compared with the GPP products generated by He et al.73,74. HCSIF exhibits superior agreement with this high spatial resolution GPP product compared to the original TROPOMI SIF, possibly because the higher spatial resolution of HCSIF allows for a better representation of GPP73,81. HCSIF shows a higher r value with GPP in most regions. In the North China Plain and Northeast China Plain, the r value between SIF and GPP approached 1, accompanied by a substantial regression slope exceeding 10 (mg CO2/m2/s/ mW/m2/nm/sr). However, in high-altitude regions such as Tibet and Qinghai, as well as in the southern coastal areas, the r value between SIF and GPP is lower. This discrepancy may be attributed to estimation errors in SIF induced by high altitudes and complex topography, impacting the capacity of SIF to accurately represent GPP82. In summary, our HCSIF agrees well with GPP products in China, the HCSIF possesses the capability to finely characterize the potential of GPP.

Figure 12 shows the distributions of HCSIF, the original TROPOMI SIF, GPP in regions characterized by diverse terrains. Compared to the original TROPOMI SIF, HCSIF can better capture the texture and detail features in the GPP. The scatter plots demonstrate that HCSIF exhibits fine consistency (r>0.6) with GPP under different terrain conditions.

Comparison of HCSIF, original TROPOMI SIF, GPP and the scatter comparison between the HCSIF and GPP estimated at 500 m; the white area represents the invalid data. (a–d) The Yellow-Huaihe-Haihe River Plain, (e–h) The Sichuan Basin, (i–l) the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau, (m–p) and the Middle–Lower Yangtze Plain.

Usage Notes

We present a high spatiotemporal resolution (500 m, 8-day) long-term (2000–2022) dataset of SIF named HCSIF for China. Our HCSIF dataset was generated using multiple features related to SR, LST, fPAR, meteorological factors, and topography. A weighted ensemble learning algorithm incorporating three base learners (CatBoost, RF, and GBDT) was employed to construct the downscaling model. The HCSIF dataset significantly improves the spatial resolution of TROPOMI SIF, which facilitates better representation of spatial details (Figs. 10, 12). This enhancement leads to high accuracy in the validation of SIF and GPP, both at the site level (Figs. 7, 8) and through satellite observations (Figs. 9, 11).

Due to limitations in the distribution of validation data, computational resources, and data processing capabilities, this dataset focuses on the period from March to October in China, which corresponds to the growing season for the main growth periods of crops and farmland83,84. For SIF that falls outside the spatiotemporal range of this dataset, such as regions globally or evergreen forests present in winter in China, further analysis with other SIF datasets from different sources may be beneficial85. Moreover, to mitigate the effects of cloud, we adopted the approach used in most studies and selected clear-sky SIF data with cloud fractions of less than 0.254,86,87, utilizing cos (SZA) to represent clear-sky PAR. This approach may lead to overestimations of GPP and photosynthesis under actual weather conditions88. Thus, additional cloud removal algorithms may be required to accurately characterize SIF in complex weather conditions. The HCSIF dataset effectively reflects terrestrial ecological processes at fine scales, enabling long-term monitoring and precise assessment of abiotic stress, vegetation phenology, vegetation transpiration, and crop yield estimation.

Code availability

The codes used to generate HCSIF are available to the public at https://github.com/Tao-shiyu/HCSIF_Generate.git.

References

Yu, Z., Zhang, F., Gao, C., Mangi, E. & Ali, C. The potential for bioenergy generated on marginal land to offset agricultural greenhouse gas emissions in China. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 189, 113924 (2024).

Jin, J. et al. Stand carbon storage and net primary production in China’s subtropical secondary forests are predicted to increase by 2060,. Carbon Balance and Management 17, 6 (2022).

Li, Z., Zhang, L., Wang, W. & Ma, W. Assessment of carbon emission and carbon sink capacity of China’s marine fishery under carbon neutrality target,. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 10, 1179 (2022).

Fang, J. Ecological perspective on carbon neutrality. Journal of Plant Ecology 45, 1173–1176 (2021).

Alemu, S. T. Photosynthesis limiting stresses under climate change scenarios and role of chlorophyll fluorescence: A review article. Cogent Food & Agriculture 6, 1785136 (2020).

Park, T. et al. Changes in timing of seasonal peak photosynthetic activity in northern ecosystems. Global Change Biology 25, 2382–2395 (2019).

Wang, T. et al. Emerging negative impact of warming on summer carbon uptake in northern ecosystems. Nature Communications 9, 5391 (2018).

Gangopadhyay, P. K., Shirsath, P. B., Dadhwal, V. K. & Aggarwal, P. K. A new two-decade (2001–2019) high-resolution agricultural primary productivity dataset for India. Scientific Data 9, 730 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Non-linear correlations exist between solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence and canopy photosynthesis in a subtropical evergreen forest in Southwest China. Ecological Indicators 157, 111311 (2023).

Frankenberg, C. et al. Prospects for chlorophyll fluorescence remote sensing from the Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2. Remote Sensing of Environment 147, 1–12 (2014).

Köhler, P. et al. Global retrievals of solar‐induced chlorophyll fluorescence with TROPOMI: First results and intersensor comparison to OCO‐2,. Geophysical Research Letters 45, 10456–10463 (2018).

Du, S. et al. Retrieval of global terrestrial solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence from TanSat satellite. Science Bulletin 63, 1502–1512 (2018).

Porcar-Castell, A. et al. Linking chlorophyll a fluorescence to photosynthesis for remote sensing applications: mechanisms and challenges. Journal of Experimental Botany 65, 4065–4095 (2014).

Baker, N. R. Chlorophyll fluorescence: a probe of photosynthesis in vivo. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 59, 89–113 (2008).

Mohammed, G. H. et al. Remote sensing of solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence (SIF) in vegetation: 50 years of progress. Remote Sensing of Environment 231, 111177 (2019).

Joiner, J. et al. First observations of global and seasonal terrestrial chlorophyll fluorescence from space. Biogeosciences 8, 637–651 (2011).

Joiner, J. et al. Global monitoring of terrestrial chlorophyll fluorescence from moderate-spectral-resolution near-infrared satellite measurements: methodology, simulations, and application to GOME-2. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques 6, 2803–2823 (2013).

Kohler, P., Guanter, L. & Joiner, J. A linear method for the retrieval of sun-induced chlorophyll fluorescence from GOME-2 and SCIAMACHY data. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques 8, 2589–2608 (2015).

Zhang, Z. et al. Global modeling diurnal gross primary production from OCO-3 solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence. Remote Sensing of Environment 285, 113383 (2023).

Joiner, J. et al. Global monitoring of terrestrial chlorophyll fluorescence from moderate spectral resolution near-infrared satellite measurements: Methodology, simulations, and application to GOME-2. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques Discussions 6, 3883–3930 (2013).

Doughty, R. et al. Global GOSAT, OCO-2, and OCO-3 solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence datasets. Earth System Science Data 14, 1513–1529 (2022).

Turner, A. J. et al. A double peak in the seasonality of California’s photosynthesis as observed from space,. Biogeosciences 17, 405–422 (2020).

Haddad, N. M. et al. Habitat fragmentation and its lasting impact on Earth’s ecosystems. Science Advances 1, e1500052 (2015).

Gensheimer, J., Turner, A. J., Köhler, P., Frankenberg, C. & Chen, J. A convolutional neural network for spatial downscaling of satellite-based solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence (SIFnet). Biogeosciences 19, 1777–1793 (2022).

Siegmann, B. et al. Downscaling of far-red solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence of different crops from canopy to leaf level using a diurnal data set acquired by the airborne imaging spectrometer HyPlant. Remote Sensing of Environment 264, 112609 (2021).

Yu, L., Wen, J., Chang, C., Frankenberg, C. & Sun, Y. High-resolution global contiguous SIF of OCO-2. Geophysical Research Letters 46, 1449–1458 (2019).

Chen, X. et al. A long-term reconstructed TROPOMI solar-induced fluorescence dataset using machine learning algorithms. Scientific Data 9, 427 (2022).

Hong, Z. et al. An operational downscaling method of solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence (SIF) for regional drought monitoring. Agriculture 12, 547 (2022).

Hu, J. C., Liu, L. Y., Yu, H. Y., Guan, L. L. & Liu, X. J., Upscaling GOME-2 SIF from clear-sky instantaneous observations to all-sky sums leading to an improved SIF-GPP correlation, Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 306 (2021).

Kang, X., Huang, C., Zhang, L., Zhang, Z. & Lv, X. Downscaling solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence for field-scale cotton yield estimation by a two-step convolutional neural network. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 201, 107260 (2022).

Cui, S., Yin, Y., Wang, D., Li, Z. & Wang, Y. A stacking-based ensemble learning method for earthquake casualty prediction. Applied Soft Computing 101, 107038 (2021).

Galicia, A., Talavera-Llames, R., Troncoso, A., Koprinska, I. & Martínez-Álvarez, F. Multi-step forecasting for big data time series based on ensemble learning. Knowledge-Based Systems 163, 830–841 (2019).

Jin, Y., Fan, H. & Liu, Y., A Downscaled Monthly Solar-Induced Chlorophyll Fluorescence Product at 0.5-Degree Resolution Over East Asia During 1995-2003, IGARSS 2023-2023 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, 7439-7442 (2023).

Engler, R. et al. 21st century climate change threatens mountain flora unequally across Europe. Global Change Biology 17, 2330–2341 (2011).

Li, X., Wang, L., Hu, B., Chen, D. & Liu, R. Contribution of vanishing mountain glaciers to global and regional terrestrial water storage changes. Frontiers in Earth Science 11, 1134910 (2023).

Shi, J., Li, C. & Yan, X. Artificial intelligence for load forecasting: A stacking learning approach based on ensemble diversity regularization. Energy 262, 125295 (2023).

Tao, S. et al. Retrieving soil moisture from grape growing areas using multi-feature and stacking-based ensemble learning modeling. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 204, 107537 (2023).

Wan, Z. New refinements and validation of the collection-6 MODIS land-surface temperature/emissivity product. Remote Sensing of Environment 140, 36–45 (2014).

Sulla-Menashe, D., Gray, J. M., Abercrombie, S. P. & Friedl, M. A. Hierarchical mapping of annual global land cover 2001 to present: The MODIS Collection 6 Land Cover product. Remote Sensing of Environment 222, 183–194 (2019).

Yan, K. et al. Evaluation of MODIS LAI/FPAR product collection 6. Part 2: Validation and intercomparison. Remote Sensing 8, 460 (2016).

Hayakawa, Y. S., Oguchi, T. & Lin, Z., Comparison of new and existing global digital elevation models: ASTER G-DEM and SRTM-3, Geophysical Research Letters, 35 (2008).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Zhang, Z. et al. The potential of satellite FPAR product for GPP estimation: An indirect evaluation using solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence. Remote Sensing of Environment 240, 111686 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. Spatio-temporal convergence of maximum daily light-use efficiency based on radiation absorption by canopy chlorophyll,. Geophysical Research Letters 45, 3508–3519 (2018).

Guanter, L. et al. Global and time-resolved monitoring of crop photosynthesis with chlorophyll fluorescence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111, E1327–E1333 (2014).

Zhang, Z. et al. Assessing bi-directional effects on the diurnal cycle of measured solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence in crop canopies. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 295, 108147 (2020).

Hu, S. & Mo, X. Detecting regional GPP variations with statistically downscaled solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence (SIF) based on GOME-2 and MODIS data. International Journal of Remote Sensing 41, 9206–9228 (2020).

Tucker, C. J. Red and photographic infrared linear combinations for monitoring vegetation. Remote Sensing of Environment 8, 127–150 (1979).

Gao, B.-C. NDWI—A normalized difference water index for remote sensing of vegetation liquid water from space,. Remote Sensing of Environment 58, 257–266 (1996).

Badgley, G., Field, C. B. & Berry, J. A. Canopy near-infrared reflectance and terrestrial photosynthesis. Science Advances 3, e1602244 (2017).

Camps-Valls, G. et al. A unified vegetation index for quantifying the terrestrial biosphere. Science Advances 7, eabc7447 (2021).

Zhang, Z., Xu, W., Qin, Q. & Long, Z. Downscaling solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence based on convolutional neural network method to monitor agricultural drought. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 59, 1012–1028 (2020).

Hu, J., Jia, J., Ma, Y., Liu, L. & Yu, H. A Reconstructed Global Daily Seamless SIF Product at 0.05 Degree Resolution Based on TROPOMI, MODIS and ERA5 Data. Remote Sensing 14, 1504 (2022).

Guanter, L. et al. The TROPOSIF global sun-induced fluorescence dataset from the Sentinel-5P TROPOMI mission. Earth System Science Data 13, 5423–5440 (2021).

Guindin-Garcia, N., Gitelson, A. A., Arkebauer, T. J., Shanahan, J. & Weiss, A. An evaluation of MODIS 8-and 16-day composite products for monitoring maize green leaf area index. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 161, 15–25 (2012).

Duan, S.-B., Li, Z.-L., Tang, B.-H., Wu, H. & Tang, R. Generation of a time-consistent land surface temperature product from MODIS data. Remote Sensing of Environment 140, 339–349 (2014).

Zhang, Z., Chen, J. M., Guanter, L., He, L. & Zhang, Y. From canopy‐leaving to total canopy far‐red fluorescence emission for remote sensing of photosynthesis: First results from TROPOMI. Geophysical Research Letters 46, 12030–12040 (2019).

Yuan, W. et al. Increased atmospheric vapor pressure deficit reduces global vegetation growth. Science Advances 5, eaax1396 (2019).

Wang, X., Wang, C. & Li, Q. Wind regimes above and below a temperate deciduous forest canopy in complex terrain: Interactions between slope and valley winds. Atmosphere 6, 60–87 (2014).

Tan, K. et al. Estimating the distribution trend of soil heavy metals in mining area from HyMap airborne hyperspectral imagery based on ensemble learning. Journal of Hazardous Materials 401, 123288 (2021).

Alchanatis, V. et al. Evaluation of different approaches for estimating and mapping crop water status in cotton with thermal imaging. Precision Agriculture 11, 27–41 (2010).

Kang, P. et al. Catboost-based framework with additional user information for social media popularity prediction, Proceedings of the 27th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, 2677-2681 (2019).

Rud, R. et al. Crop water stress index derived from multi-year ground and aerial thermal images as an indicator of potato water status. Precision Agriculture 15, 273–289 (2014).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Machine learning 45, 5–32 (2001).

Wang, J., Li, P., Ran, R., Che, Y. & Zhou, Y. A short-term photovoltaic power prediction model based on the gradient boost decision tree. Applied Sciences 8, 689 (2018).

Langner, M., Toreini, P. & Maedche, A. Cognitive state detection with eye tracking in the field: an experience sampling study and its lessons learned. i-com 23, 109–129 (2024).

Popov, N. V., Razmochaeva, N. V. & Klionskiy, D. M., Investigation of algorithms for converting dimension of feature space in retail data analysis problems, 2020 9th Mediterranean Conference on Embedded Computing (MECO), 1-4 (2020).

Pelikan, M., Goldberg, D. E. & Cantú-Paz, E., BOA: The Bayesian optimization algorithm, Proceedings of the Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference GECCO-99, 1 (1999).

Zhang, Y. et al. ChinaSpec: A Network for Long-Term Ground-Based Measurements of Solar-Induced Fluorescence in China,. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences 126, e2020JG006042 (2021).

Du, S., Liu, X., Chen, J., Duan, W. & Liu, L. Addressing validation challenges for TROPOMI solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence products using tower-based measurements and an NIRv-scaled approach. Remote Sensing of Environment 290, 113547 (2023).

Yu, G.-R. et al. Overview of ChinaFLUX and evaluation of its eddy covariance measurement. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 137, 125–137 (2006).

Li, Y., Chen, J., Ma, Q., Zhang, H. K. & Liu, J. Evaluation of Sentinel-2A surface reflectance derived using Sen2Cor in North America. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 11, 1997–2021 (2018).

He, S. et al. A daily and 500 m coupled evapotranspiration and gross primary production product across China during 2000–2020. Earth System Science Data 14, 5463–5488 (2022).

Zhang, Y. & He, S., PML-V2 (China): evapotranspiration and gross primary production dataset (2000.02.26-2020.12.31), National Tibetan Plateau Data Center, https://doi.org/10.11888/Terre.tpdc.272389 (2022).

Tao, S. et al. A high-resolution satellite-based solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence dataset for China from 2000 to 2022, Science Data Bank, https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.16910 (2024).

Li, X., Xiao, J. & He, B. Chlorophyll fluorescence observed by OCO-2 is strongly related to gross primary productivity estimated from flux towers in temperate forests. Remote Sensing of Environment 204, 659–671 (2018).

Kiyono, T. et al. Regional-scale wilting point estimation using satellite SIF, radiative-transfer inversion, and soil-vegetation-atmosphere transfer simulation: A grassland study, Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences, e2022JG007074 (2023).

Zeng, Y. et al. Estimating near-infrared reflectance of vegetation from hyperspectral data. Remote Sensing of Environment 267, 112723 (2021).

Si, H., Wang, R., Wang, R. & He, Z. Can the MODIS Data Achieve the Downscaling of GOME-2 SIF? Validation of Data from China. Sustainability 15, 5920 (2023).

Bacour, C. et al. Differences between OCO-2 and GOME-2 SIF products from a model-data fusion perspective,. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences 124, 3143–3157 (2019).

Celis, J. et al. A comparison of moderate and high spatial resolution satellite data for modeling gross primary production and transpiration of native prairie, alfalfa, and winter wheat. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 344, 109797 (2024).

Xie, X. et al. A practical topographic correction method for improving Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer gross primary productivity estimation over mountainous areas. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 103, 102522 (2021).

Wang, H. et al. Alpine grassland plants grow earlier and faster but biomass remains unchanged over 35 years of climate change. Ecology Letters 23, 701–710 (2020).

Liu, Y., Wang, E., Yang, X. & Wang, J. Contributions of climatic and crop varietal changes to crop production in the North China Plain, since 1980s. Global Change Biology 16, 2287–2299 (2010).

Song, Z. et al. Effects of winter chilling and photoperiod on leaf-out and flowering in a subtropical evergreen broadleaved forest in China. Forest Ecology and Management 458, 117766 (2020).

Zhang, Y., Joiner, J., Alemohammad, S. H., Zhou, S. & Gentine, P. A global spatially contiguous solar-induced fluorescence (CSIF) dataset using neural networks. Biogeosciences 15, 5779–5800 (2018).

Yang, J. et al. TROPOMI SIF reveals large uncertainty in estimating the end of plant growing season from vegetation indices data in the Tibetan Plateau. Remote Sensing of Environment 280, 113209 (2022).

Xiao, J. et al. Remote Sensing of the terrestrial carbon cycle: A review of advances over 50 years. Remote Sensing of Environment 233, 111383 (2019).

Wang, X. et al. Vegetation primary production estimation at maize and alpine meadow over the Heihe River Basin, China. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 17, 94–101 (2012).

Du, S. et al. SIFSpec: Measuring solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence observations for remote sensing of photosynthesis. Sensors 19, 3009 (2019).

Liu, L. et al. Estimating maize GPP using near-infrared radiance of vegetation. Science of Remote Sensing 2, 100009 (2020).

Zhang, Z. et al. Reduction of structural impacts and distinction of photosynthetic pathways in a global estimation of GPP from space-borne solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence. Remote Sensing of Environment 240, 111722 (2020).

Wang, Y., Zhou, G. & Wang, Y. Environmental effects on net ecosystem CO2 exchange at half-hour and month scales over Stipa krylovii steppe in northern China. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 148, 714–722 (2008).

Li, Z. et al. Solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence and its link to canopy photosynthesis in maize from continuous ground measurements. Remote Sensing of Environment 236, 111420 (2020).

Hou, Y., Zhou, G., Xu, Z., Liu, T. & Zhang, X. Interactive effects of warming and increased precipitation on community structure and composition in an annual forb dominated desert steppe. PLoS one 8, e70114 (2013).

Hao, Y. B. et al. Predominance of precipitation and temperature controls on ecosystem CO2 exchange in Zoige alpine wetlands of Southwest China. Wetlands 31, 413–422 (2011).

Zhou, L., Zhou, G., Liu, S. & Sui, X. Seasonal contribution and interannual variation of evapotranspiration over a reed marsh (Phragmites australis) in Northeast China from 3-year eddy covariance data,. Hydrological Processes: An International Journal 24, 1039–1047 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Pro-vince (BK20240068), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFF1301900), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42125105, 42071388, 42101320) and the Inner Mongolia Meteorological Bureau Science and Technology Innovation Project (nmqxkjcx202422).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: S.Y.T., J.M.C., Z.Y.Z.; Data curation: S.Y.T., Z.Y.Z., Y.G.Z.;W.M.J, T.T.Z.,L.S.W.,Y.F.W.; Formal analysis: S.Y.T., J.M.C., Z.Y.Z., X.Y, K.; Funding acquisition: J.M.C., Z.Y.Z.; Investigation: S.Y.T., Z.Y.Z., Y.G.Z., W.M.J.; Methodology: S.Y.T., J.M.C., Z.Y.Z.; Software: S.Y.T., W.M.J., Z.Y.Z.; Supervision: J.M.C., Z.Y.Z., Y.G.Z., W.M.J.; Validation: Y.G.Z.,W.M.J.,T.T.Z.,L.S.W.,Y.F.W.; Visualization: S.Y.T., Z.Y.Z., Y.G.Z., X.Y.K.; Writing—original draft:. S.Y.T; Writing—review & editing: J.M.C., Z.Y.Z., Y.G.Z., Any questions on the dataset, please contact: Prof. Jingming Chen or Prof. Zhaoying Zhang.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tao, S., Chen, J.M., Zhang, Z. et al. A high-resolution satellite-based solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence dataset for China from 2000 to 2022. Sci Data 11, 1286 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-04101-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-04101-6

This article is cited by

-

Assessing the potential fire tolerance of conifer saplings in cold and wet environments using a pyro-ecophysiology approach

Fire Ecology (2026)

-

Improved estimation of forage nitrogen in alpine grassland by integrating Sentinel-2 and SIF data

Plant Methods (2025)

-

Maize yield estimation in Northeast China’s black soil region using a deep learning model with attention mechanism and remote sensing

Scientific Reports (2025)