Abstract

Third-generation epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKIs) are the latest and a vital treatment option for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients. Although EGFR-sensitive mutations are an indication for third-generation EGFR-TKI therapy, 30% of NSCLC patients lack response and all patients inevitably progress. There is a lack of biomarkers to predict the efficacy of EGFR-TKI therapy. In this report, we performed comprehensive plasma metabolomic profiling on 186 baseline and 20 post-treatment samples, analyzing 1,019 metabolites using four ultrahigh performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectroscopy (UPLC-MS/MS) methods. The dataset contains detailed clinical and metabolic information for 186 patients. Rigorous quality control measures were implemented. No significant differences in body mass index and biochemical metabolic parameters were observed between responders and non-responders. The datasets were utilized to characterize the responsive metabolic traits of third-generation EGFR-TKI therapy. All datasets are available for download on the OMIX website. We anticipate that these datasets will serve as valuable resources for future studies investigating NSCLC metabolism and for the development of personalized therapeutic strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Lung cancer led to an estimated 2.2 million new cases and 1.8 million deaths in 2020 globally, which remains a major public health concern1. China is facing a serious lung cancer burden with a total of 1,060,600 new lung cancer cases and 733,300 lung cancer deaths in 20222. Non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the major histological subtype which consists of more than eighty percent of all lung cancer patients. Somatic activating mutations in epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) predominantly drive NSCLC, which is mainly observed in Asian NSCLC patients with a frequency of 51.4%3. Thus EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitor (EGFR-TKI) is an important treatment strategy for Asian patients. First-and second-generation EGFR-TKIs such as gefitinib, erlotinib, afatinib, and dactinib have become the standard first-line treatment for patients with EGFR-sensitive mutations in NSCLC4,5. The EGFR T790M mutation is the dominant acquired resistance mutation to first-generation and second-generation EGFR-TKIs, which necessitated the development of third-generation EGFR-TKIs6,7. Multiple clinical trials have shown that third-generation EGFR-TKI can not only target EGFR T790M mutation, but also show better efficacy than first-generation or second-generation EGFR-TKIs in first-line treatment of patients with EGFR-sensitive mutation8,9,10,11. While EGFR-sensitive patients inevitably develop drug resistance. Previous clinical studies have suggested that the efficacy of EGFR-TKIs should be evaluated before clinical decision-making to guide alternative treatments for those at high risk for poor efficacy in advance12,13,14. However, no known biomarkers currently exist that can predict which patients may not benefit from TKIs, thus placing them at risk for rapid disease progression.

EGFR T790M mutation detection is the gold standard for predicting which patients could gain additional survival benefits from EGFR-TKI therapy. However, not all EGFR T790M mutant patients could respond and genotype detection lacks adequate sensitivity to stratify the potential survival benefit for precise clinical decisions. The objective response rate for patients with T790M mutation treated with third-generation EGFR-TKIs is about 70%15, and about 50% of these patients will inevitably relapse within 9–10 months15. Furthermore, the patients who respond to EGFR-TKI have a median PFS of 9.5 months15. Thus, a better approach that could accurately predict the efficacy and survival benefit of third-generation EGFR-TKIs is urgently needed.

Despite researches on some mechanisms of resistance to third-generation EGFR-TKIs, including EGFR-dependent resistance such as mutations EGFR C797S, L792X, G796X, L718Q, and EGFR-independent resistance such as MET amplification, ERBB2 amplification, etc., 30%–50% of the resistance mechanisms remain unknown. Recent studies suggest that resistance to third-generation EGFR-TKIs is associated with metabolic reprogramming, such as alterations in carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. The upregulation of molecules related to lipid metabolism, such as stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 (SCD1), fatty acid synthase (FASN), and bone morphogenetic proteins 4 (BMP4) can induce resistance to third-generation EGFR-TKIs16,17,18,19. In addition to fatty acid metabolism, resistant cell lines show increased uptake of glutamine, and inhibiting glutamine uptake can enhance the sensitivity to osimertinib20. While comprehensive metabolism is still lacking to portray the distinct metabolic pattern related to third-generation EGFR-TKI efficacy and prognosis.

Human blood is one of the most commonly used samples for assessing an individual’s health. Blood contains metabolites that reflect the functional status of internal organs and the effects of cellular damage. Interpreting changes in blood metabolites is essential for understanding the pathological mechanisms of diseases and identifying potential prognostic biomarkers. Metabolomics is an effective tool for accurately assessing the current status of organisms and revealing the specific biochemical processes occurring within them21.

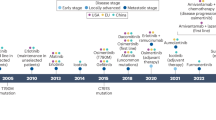

Rezivertinib (BPI-7711) is a novel third-generation EGFR-TKI. The objective response rate (ORR) ranged from 59.3% to 83.7% and the median DoR was 19.3 months. BPI-7711 has shown promising efficacy and safety for treatment of NSCLC patients with EGFR mutation. Here, we present a plasma metabolism dataset of 186 EGFR-sensitive NSCLC patients enrolled from phase I and phase IIa clinical studies of BPI-771122,23,24. The metabolomic profiling was performed on plasma samples collected at the time of baseline and post-treatment (Fig. 1). Additionally, we conducted whole-exome sequencing for 49 patients and proteomics for 14 patients. The metabolite quantification included four profiling modes: Method 1-2: two separate reverse-phase ultra-performance liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (RP/UPLC-MS/MS) methods with positive ion mode electrospray ionization (ESI); Method 3: RP/UPLC-MS/MS with negative ion mode ESI; Method 4: hydrophilic interaction chromatography (HILIC)/UPLC-MS/MS with negative ion mode ESI. We identified 1,019 metabolites, involving nine classes and 120 pathways. We have made these data, together with the corresponding rich clinical annotations, publicly available to the scientific community.

Methods

The EGFR-mutated-NSCLC patients treated with third-generation EGFR-TKI were collected from September 11, 2017, to August 23, 2019. Details of inclusion and exclusion criteria have been provided in previous clinical trial studies23,24. In brief, patients aged 18–75 years must have locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC confirmed by histology or cytology. Additionally, patients were required to have EGFR-sensitive mutations (including G719X, exon 19 deletion, L858R, L861Q, etc.) with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) score of 0 to 1. In addition, other inclusion criteria contained adequate bone marrow function (thrombocytes ≥ 100 × 109/L, hemoglobin ≥ 90 g/L, absolute neutrophil count ≥ 1.5 × 109/L), liver function (total bilirubin ≤ 1.5 times the upper limit of normal (ULN), alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) ≤ 3 times ULN, creatinine ≤ 1.5 times ULN or creatinine clearance ≥ 50 mL/min). All patients signed written informed consent.

Exclusion criteria included a history of recurrent or concomitant malignant tumors in the past 5 years, previous treatment with any third-generation EGFR-TKI, history of interstitial lung disease, known active infections (such as hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and human immunodeficiency virus infection), significant cardiac dysfunction (corrected QT interval of electrocardiogram > 470 msec, complete left bundle branch block, degree III conduction block, degree II conduction block, etc.).

We maintained consistent sample collection procedures, including an overnight fast before venous blood extraction, which took place at a similar time in the morning to exclude the effects of diet according to the previous study. All patients did not receive nutritional support therapy before blood sample collection. Dynamic samples were collected at the following time points: before BPI-7711 treatment, at the 3rd cycle of BPI-7711 treatment, and at the time of disease progression. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Cancer Center/Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, and the approval number was 17–056/1311. Written informed consent signed and dated by the patients has been obtained.

Sample collection processing

Samples of whole blood (4 mL) were collected in a vacutainer tube that contained the anticoagulant EDTA and should immediately be placed on ice. The plasma was collected after centrifugation at 4 °C within 30 minutes of collection. The screw-capped polypropylene cryogenic sample tube must be labeled with the subject’s medical history number, name, subject number, clinical study project number, clinical protocol time, dose, and date. Samples were stored at −80 °C for further analysis.

Sample preparation

Untargeted metabolomics analysis was performed by Calibra Lab at DIAN Diagnostics (Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China). Ethanol was added to inactivate potential viruses and samples were dried for further treatment. Methanol was added to each sample in a ratio of 1:4. After vortexing and mixing for 3 minutes, the denatured proteins were centrifuged at 20 °C at a speed of 6526 rpm for 10 minutes after which the supernatant containing diverse metabolites was transferred into a new tube. To ensure reliability and accuracy of the detection, the resulting supernatant was divided into four fractions: two for analysis by two separate reverse-phase ultra-performance liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (RP/UPLC-MS/MS) methods with positive ion mode ESI, one for analysis by RP/UPLC-MS/MS with negative ion mode ESI, one for analysis by HILIC/UPLC-MS/MS with negative ion mode ESI. Subsequently, 100 μL supernatant (quadruplicate samples) was added into four wells respectively and blow-dried with nitrogen for subsequent UPLC-MS/MS detection.

Ultrahigh performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectroscopy (UPLC-MS/MS)

The four UPLC-MS/MS methods were conducted using an ACQUITY 2D UPLC system (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) coupled with a Q Exactive hybrid Quadrupole-Orbitrap mass spectrometer, including a HESI-II heated ESI source and Orbitrap mass analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, USA). The mass spectrometer was operated at 35,000 mass resolution (at 200 m/z) with a scan range of 70–1000 m/z. The MS capillary temperature was set at 350°C, and sheath and auxiliary gas flow rates were maintained at 40 and 5 units, respectively, for both positive and negative ESI methods.

In the first method, the Q Exactive was set to positive ESI mode with a C18 reverse-phase column (UPLC BEH C18, 2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 µm; Waters); the gradient elution consisted of water (solvent A) and methanol (solvent B), both containing 0.05% perfluoropentanoic acid (PFPA) and 0.1% formic acid (FA). The gradient for C18 column usage included a seven-minute run where the polar mobile phase increased from 5% to 95%. The second method, using the same column and positive ESI mode, featured a solvent system optimized for more hydrophobic compounds, consisting of methanol, acetonitrile, and water with 0.05% PFPA and 0.01% FA. For the third method, negative ESI mode was employed with the above C18 column, and the elution solvents comprised water and methanol in 6.5 mM ammonium bicarbonate at pH 8. The fourth method utilized a HILIC column (UPLC BEH Amide, 2.1 × 150 mm, 1.7 µm; Waters) and negative ESI mode. Here, the eluents were water (A) and acetonitrile (B), containing 10 mM ammonium formate, and gradient elution was performed in a seven-minute run with the polar phase decreasing from 80% to 20%. The Q Exactive’s mass spectrometer analysis alternated between MS and data-dependent MS2 scans using dynamic exclusion.

Data extraction and compound identification

Peak lookup/alignment, and peak annotation were conducted on CalOmics platform. The identification of metabolites was conducted by searching an in-house library comprising more than 3,300 standards, with data entries in the library generated by analyzing purified standards on the experimental platforms. Metabolite identification should meet three strict criteria: retention index (RI) within a narrow RI window, accurate mass with a variation less than 10 ppm, and MS/MS spectra with high forward and reverse searching scores. All identified metabolites satisfied the level 1 criteria established by the Chemical Analysis Working Group (CAWG) of the Metabolomics Standards Initiative (MSI), except for certain lipids marked with an asterisk, whose MS/MS spectra were matched in silico. The peak area for each metabolite was quantified using area under the curve.

Prior to statistical analysis, raw peak areas underwent normalization to compensate for system variability across different analytical runs. Subsequently, these normalized values were logarithmically transformed (log2) to alleviate skewness and approximate a normal (Gaussian) distribution. Metabolites with over 80% missing ratios in all participants were removed from the datasets. Missing values were imputed with the 1/5 of the minimum positive values of each metabolite.

Metabolites exhibiting significant alterations between responders and non-responders were identified using the SAMseq algorithm. In addition, we employed multivariate analytical techniques including principal component analysis (PCA) by R package “factoextra” (version 1.0.7) and logistic regression using R package glmnet (version 4.1–8). All analyses were performed using R software (version 4.3.3).

Data Records

The raw spectra and raw ion peak area data for each metabolite, along with the preprocessed metabolomics data and clinical data are accessible on the OMIX platform under the dataset IDs OMIX00444325 and OMIX00678726. To download the data, please visit the following links: ‘https://download.cncb.ac.cn/OMIX/OMIX004443/’ and ‘https://download.cncb.ac.cn/OMIX/OMIX006787/’. The OMIX004443 dataset contains the raw spectra for each sample. The OMIX006787 dataset is available as a zip file named ‘BPI-7711.zip’, which includes several files. Specifically, you will find ‘BPI-7711-metabolomicsdata.xlsx’, which contains the raw metabolism data in Sheet 1, and the preprocessed metabolomics data in Sheet 2. Additionally, ‘BPI-7711-clinicaldata.xlsx’ provides detailed clinical information. Furthermore, a text document, titled ‘preprocessing-strategy.docx’, elucidates the methodologies employed during the data preprocessing phase.

The raw ion peak area data matrix contained 1,019 metabolite abundances. The names of 1,019 metabolites are annotated at MSI level 1 (tab “COMPOUND Name” in file BPI-7711-metabolomicsdata.xlsx) covering 120 metabolic pathways (tab “SUB META PATHWAY” in file BPI-7711-metabolomicsdata.xlsx) across 9 molecular classes (tab “SUPER META PATHWAY” in file BPI-7711-metabolomicsdata.xlsx). The preprocessed data (tab “Normalized data” in file BPI-7711-metabolomicsdata.xlsx) were generated as described in Section “Data extraction and compound identification” and metabolites exhibiting over 80% missing ratios in all participants were removed from the datasets. The preprocessed data matrix includes 951 metabolites encompassing 112 metabolic pathways. In the clinical data file, a detailed description of each clinical variable is presented in sheet 1.

Technical Validation

To mitigate systematic biases, samples were randomized across profiling days, as well as within each profiling run and plate. Quality control samples were generated by combining a small amount of aliquots from each NSCLC sample and one QC sample was analyzed for every ten NSCLC samples throughout the detection.

Instrument variability was assessed by calculating the median relative standard deviation (RSD) of the internal standards added to each sample before processing and injection, with a threshold set at 5%. The median RSD for the metabolomic data was 4.64%, which met the stipulated quality control criteria. Furthermore, the influence of pre-analytical variables on the metabolomic outcomes was investigated. All participating centers strictly followed the sample processing guidelines defined in the clinical trial protocol. PCA demonstrated that samples clustered closely together (Fig. 2a), elucidating that there was no significant variability between samples of different centers during phase I clinical trial (F = 1.25, p = 0.085, multivariate analysis of variance) and in phase IIa clinical trial either (F = 1.30, p = 0.234, multivariate analysis of variance). The first ten principal components explained 44% and 70% of the total variance in the metabolism datasets of phase I and phase IIa cohorts, respectively (Fig. S1). The cohort was categorized into two groups: responders (complete and partial, n = 122) and non-responders (stable and progressive disease, n = 64). To address potential confounding factors of nutritional status and cancer cachexia, we compared the body mass index (BMI) between responder and non-responder groups in phase I and phase II cohorts, finding no significant difference as shown in Table 1, Fig. 2b and Fig. S1. Additionally, biochemical markers of metabolism, such as glucose, cholesterol, albumin, and triglycerides, did not differ significantly between responders and non-responders (Fig. 2b and Fig. S1).

PCA of the metabolic data and forest plot of confounding factors on outcomes. (a) PCA of the metabolic data of phase I and phase IIa cohorts. The colors indicate the centers where samples were collected. (b) Logistic regression analysis of clinical features and metabolic indicators on the outcomes responders (R) and non-responders (NR). In the analysis, NR was considered a risk factor and represented the outcome variable “1”. The model was adjusted for potential confounders, and the odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated to evaluate the impact of each variable on the likelihood of being a non-responder. BMI: body mass index; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; ALT/AST: the ratio of alanine aminotransferase to aspartate aminotransferase; ALP: alkaline phosphatase; ALB: albumin; TC: total cholesterol; Tgly: triglycerides; Glu: glucose; Ccr: creatinine clearance rate; uPH: urine potential of hydrogen.

Code availability

The data preprocessing scripts are publicly available on GitHub named “Plasma-metabolomics-profiling-of-EGFR-mutant-NSCLC-patients-treated-with-third-generation-EGFR-TKI” which can be accessed via the following link: https://github.com/Ninglou123/Plasma-metabolomics-profiling-of-EGFR-mutant-NSCLC-patients-treated-with-third-generation-EGFR-TKI.

References

Leiter, A., Veluswamy, R. R. & Wisnivesky, J. P. The global burden of lung cancer: current status and future trends. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 20, 624–639 (2023).

Zheng, R. S. et al. Cancer incidence and mortality in China, 2022. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi 46, 221–231 (2024).

Shi, Y. et al. A prospective, molecular epidemiology study of EGFR mutations in Asian patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer of adenocarcinoma histology (PIONEER). J Thorac Oncol 9, 154–162 (2014).

Tan, C. S., Gilligan, D. & Pacey, S. Treatment approaches for EGFR-inhibitor-resistant patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Lancet Oncol 16, e447–e459 (2015).

Pao, W. et al. EGF receptor gene mutations are common in lung cancers from “never smokers” and are associated with sensitivity of tumors to gefitinib and erlotinib. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101, 13306–13311 (2004).

Jänne, P. A. et al. AZD9291 in EGFR inhibitor-resistant non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 372, 1689–1699 (2015).

Shi, Y. et al. Efficacy, safety, and genetic analysis of furmonertinib (AST2818) in patients with EGFR T790M mutated non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase 2b, multicentre, single-arm, open-label study. Lancet Respir Med 9, 829–839 (2021).

Shi, Y. et al. Furmonertinib (AST2818) versus gefitinib as first-line therapy for Chinese patients with locally advanced or metastatic EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (FURLONG): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised phase 3 study. Lancet Respir Med 10, 1019–1028 (2022).

Ramalingam, S. S. et al. Osimertinib As First-Line Treatment of EGFR Mutation-Positive Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol 36, 841–849 (2018).

Zhao, Y. et al. Efficacy and safety of first line treatments for patients with advanced epidermal growth factor receptor mutated, non-small cell lung cancer: systematic review and network meta-analysis. Bmj 367, l5460 (2019).

Soria, J. C. et al. Osimertinib in Untreated EGFR-Mutated Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 378, 113–125 (2018).

Crystal, A. S. et al. Patient-derived models of acquired resistance can identify effective drug combinations for cancer. Science 346, 1480–1486 (2014).

Soucheray, M. et al. Intratumoral Heterogeneity in EGFR-Mutant NSCLC Results in Divergent Resistance Mechanisms in Response to EGFR Tyrosine Kinase Inhibition. Cancer Res 75, 4372–4383 (2015).

Zhou, C. & Yao, L. D. Strategies to Improve Outcomes of Patients with EGRF-Mutant Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Review of the Literature. J Thorac Oncol 11, 174–186 (2016).

Blumenthal, G. M. et al. Overall response rate, progression-free survival, and overall survival with targeted and standard therapies in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: US Food and Drug Administration trial-level and patient-level analyses. J Clin Oncol 33, 1008–1014 (2015).

Huang, Q. et al. Co-administration of 20(S)-protopanaxatriol (g-PPT) and EGFR-TKI overcomes EGFR-TKI resistance by decreasing SCD1 induced lipid accumulation in non-small cell lung cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 38, 129 (2019).

Kunimasa, K. et al. Glucose metabolism-targeted therapy and withaferin A are effective for epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor-induced drug-tolerant persisters. Cancer Sci 108, 1368–1377 (2017).

Zhang, K. R. et al. Targeting AKR1B1 inhibits glutathione de novo synthesis to overcome acquired resistance to EGFR-targeted therapy in lung cancer. Sci Transl Med 13, eabg6428 (2021).

Ali, A. et al. Fatty acid synthase mediates EGFR palmitoylation in EGFR mutated non-small cell lung cancer. EMBO Mol Med 10 (2018).

Liu, Y. et al. Restricting Glutamine Uptake Enhances NSCLC Sensitivity to Third-Generation EGFR-TKI Almonertinib. Front Pharmacol 12, 671328 (2021).

Wishart, D. S. Emerging applications of metabolomics in drug discovery and precision medicine. Nat Rev Drug Discov 15, 473–484 (2016).

Shi, Y. et al. Safety, Efficacy, and Pharmacokinetics of Rezivertinib (BPI-7711) in Patients With Advanced NSCLC With EGFR T790M Mutation: A Phase 1 Dose-Escalation and Dose-Expansion Study. J Thorac Oncol 17, 708–717 (2022).

Shi, Y. et al. Efficacy and Safety of Rezivertinib (BPI-7711) in Patients With Locally Advanced or Metastatic/Recurrent EGFR T790M-Mutated NSCLC: A Phase 2b Study. J Thorac Oncol 17, 1306–1317 (2022).

Shi, Y. et al. Results of the phase IIa study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of rezivertinib (BPI-7711) for the first-line treatment of locally advanced or metastatic/recurrent NSCLC patients with EGFR mutation from a phase I/IIa study. BMC Med 21, 11 (2023).

Lou, N. et al. OMIX https://download.cncb.ac.cn/OMIX/OMIX004443 (2023).

Lou, N. et al. OMIX https://download.cncb.ac.cn/OMIX/OMIX006787 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This project was financially supported by CAMS InnovationFund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS 2021-I2M-1-003); National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (2022-PUMCHB-033); Major Project of Medical Oncology Key Foundation of Cancer Hospital Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (CICAMS-MOMP2022006); National Natural Science Foundation of China (81972805).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.H.H. and Y.K.S. designed the study, revised the paper and provided funding. N.L. and R.Y.G. performed the experiments, bioinformatic and statistical analysis of the data. N.L. wrote the original manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lou, N., Gao, R., Shi, Y. et al. Plasma metabolomics profiling of EGFR-mutant NSCLC patients treated with third-generation EGFR-TKI. Sci Data 11, 1369 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-04169-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-04169-0

This article is cited by

-

Applications of artificial intelligence in non–small cell lung cancer: from precision diagnosis to personalized prognosis and therapy

Journal of Translational Medicine (2025)