Abstract

Accurately quantifying agricultural water use is essential for protecting agricultural systems from the risk of water scarcity and promoting sustainable water management. While previous studies have innovatively provided spatially explicit analyses or datasets, they tend to have relatively coarse resolution (~8.3 km), and inadequately considered precise localization parameters. Here, we produced annual blue and green water use for 15 main crops with a resolution of 1 km for the years 1991–2019 in China. Firstly, we estimated the yearly crop blue and green water use at the site scale by incorporating more localized input parameters using a dynamic water balance model. Then, the random forest model was combined with site-scale simulation results to generate spatial predictions of blue and green water for each crop from 1991 to 2019. The resulting maps showed a high correlation with locally observed values at field stations (R2 = 0.95), statistics (R2 = 0.77), and exhibited some strengths compared with existing datasets that covered various scales. This dataset can play a key role in devising sustainable water management strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

With an increasing global population and rapid economic development, ensuring the sustainability of agricultural development while meeting human food demands has become a pressing global concern1. Freshwater resources, serving as the foundation of agricultural systems, play an essential role in ensuring food security and achieving sustainable agricultural development2,3,4. As the largest consumer of freshwater resources, global agricultural water use has surged by 124.35% over the past 40 years, constituting more than 70% of global freshwater withdrawals and nearly reaching the upper limit of blue water for agriculture on the planet5,6,7. The scarcity of freshwater presents a significant threat to the sustainability of agricultural systems. Consequently, there is an urgent need to accurately quantify agricultural water use to help stakeholders improve efficiency and formulate policies for sustainable water resource management.

Since the beginning of the 21st century, the gradual improvement of irrigation infrastructure has led to significant advancements in irrigated agriculture in China8. This has played a crucial role in promoting the production of agricultural products, with 75% of the grains production and over 90% of the cash crops production being produced on irrigated farmland, which accounts for 50% of cropland in China9. However, the inefficiency and expansion of irrigated agriculture have resulted in a continuous increase in agricultural water consumption, accounting for over 65% of China’s total freshwater consumption10. This surpasses the threshold for maintaining the stability of the Earth’s system and has caused environmental issues, such as groundwater depletion in the North China Plain and soil salinization in Northwest China11,12,13,14. Improving the efficiency of agricultural water use and managing the total amount used pose significant challenges to sustainable development in China. Additionally, the rapid development of urbanization and industrialization in China has escalated the demand for water resources, intensifying the competition between non-agricultural and agricultural water use15,16. In the future, China’s agricultural sector is poised to experience heightened water stress as a result of shifting precipitation patterns due to climate change and escalating food demand12,17,18. Consequently, it is imperative to conduct a quantitative and spatiotemporal dynamic analysis of agricultural water use in China to improve irrigation efficiency, promote the reallocation of water resources, and ensure sustainability within the agricultural system.

So far, traditional data on agricultural water consumption in China mainly relies on administrative-level statistics published by government departments, which rarely capture detailed information about specific water requirements for various crops and intra-administrative districts19,20. To address this issue, the water footprint framework has been proposed as a potential assessment avenue3,4. This framework distinguishes the water requirements for crop growth into blue water, which comes from surface or groundwater, and green water, which comes from rainwater stored in the soil at the crop roots21. Various techniques have been developed over the past two decades to estimate crop blue water use (BWU) and green water use (GWU), such as the global crop water model (GCWM)21 and the grid-based dynamic water balance model3,4. These models provide spatially explicit information on water use based on the soil balance principle and crop coefficient approach at a resolution of 5′ × 5′ (~8.3 km). For irrigated crops, the model estimates GWU as the potential evapotranspiration under water stress (without irrigation), while the BWU is defined as the difference between potential evapotranspiration with fully satisfied irrigation and GWU. For the rainfed crops, only the GWU is estimated. Although pioneering in providing spatially clear analyses of global crop water use, these studies are primarily based on crop production data from the year 2000 and lack crop-specific and year-specific datasets for the BWU and GWU4,21. Subsequently, efforts have been made to develop maps showing crop water use at a grid scale over time. For example, a global dataset of monthly crop-specific BWU and GWU for 23 main crops was obtained using the WATNEEDS model at a 5′ resolution for the years 2000 and 201622. Additionally, a crop water use map from 1990 to 2019 at a 5′ resolution was produced using a global process-based crop model with upgraded soil water balance techniques23.

In summary, the previous studies represent a significant contribution to freshwater resource management by offering innovative solutions and datasets to the challenges related to efficient water allocation and sustainable agricultural development. Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge the existence of several limitations and uncertainties that must be taken into account. Firstly, the current spatial and temporal dynamics of crop water use are usually represented with a coarse spatial resolution (~8.3 km), which may not accurately capture the spatial variability of crop water demand within grid cells. This limitation could impact the precision of water management strategies at a local level. Secondly, the integration of multiple raster data sources in these models can introduce errors that propagate across layers, potentially affecting the overall accuracy of the results. Thirdly, the requisite crop parameters used in the above models, such as crop coefficients (\({K}_{c}\)) and crop calendars, are often outdated or lack spatial heterogeneity. For instance, Chiarelli et al.22 assessed the crop water requirement for the years 2000 and 2016 using the crop planting and harvesting dates around the year 2000 and internationally used \({K}_{c}\). Similarly, Mialyk et al.23 estimated the crop water use annually since 1990 based on the static growing periods, i.e., the multi-year average estimates, rather than accounting for year-to-year variability. These studies did not fully account for the dynamic nature of agricultural practices and climate impacts on water use over time. Overall, while these studies offer valuable insights into agricultural water use, addressing the limitations mentioned above is important for enhancing the accuracy and relevance of water management strategies in the context of sustainable agricultural development.

Here, we presented annual blue and green water use for 15 major crops with a resolution of 1 km for the years 1991–2019. Firstly, following the methodology laid out by Siebert et al.21, a dynamic water balance model was applied at the site scale to estimate the crop blue and green water use for each station (Fig. S1), incorporating more localized input data for improved accuracy. Specifically, the daily reference evapotranspiration is computed by combining the modified Penman-Monteith (P-M) equation recommended by FAO with climate data observed at meteorological stations. Planting and harvested dates for the crops were determined using observational data from agro-meteorological stations in China; and \({K}_{c}\) is adjusted by the specific climatic and growing conditions of each station based on the internationally recognized values. Secondly, we employed a random forest (RF) model to spatialize the simulation results of crop water use at site scale. We validated our outcomes by comparing them with (1) locally observed values across several crops and locations from the Chinese Ecosystem Research Network (CERN) and literature; (2) provincial or municipal statistics from the National Statistics Bureau (NSB) in China; and (3) existing datasets provided by Chiarelli et al.22, Mialyk et al.23, Zhang et al.24 and Wang et al.25. The resulting dataset on crop water use holds significant potential in formulating more informed water management strategies, guiding agricultural practices, and addressing the impacts of climate change on water resources.

Methods

The study covers a comprehensive scope, encompassing 31 provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions within mainland China. Given China’s vast agricultural production and diverse crop planting structure, the research estimated the annual blue and green water use for 15 primary crops. These crops include wheat (winter wheat, spring wheat), maize (spring maize, summer maize), rice (early rice, late rice, single-season rice), soybean, potato, sugar beet, sugarcane, groundnut, rapeseed (spring rapeseed, winter rapeseed), and cotton (Fig. 1). These selected crops collectively represent a significant portion of China’s crop production and harvested area, accounting for approximately 71.77% of crop production and 76.39% of the harvested area in the country. The water use estimation differentiates between irrigated crops, for which both blue and green water use are calculated, and rainfed crops, for which only green water use is considered (Fig. 2). This comprehensive approach provides valuable insights into the water use patterns within China’s agriculture sector, essential for sustainable water resource management and agricultural planning.

Data collection

The input data for our study primarily comprises two components. The first section focuses on calculating data related to crop water use, including climate data, crop parameters, crop calendars from planting to harvested dates, crop heights, and soil data. Daily meteorological data such as air temperature, precipitation, relative humidity, wind speed, sunshine hours, and atmospheric pressure of 616 national meteorological stations from 1991 to 2019 were came from the China Meteorological Data Service Centre (CMDSC) (https://data.cma.cn/). Subsequently, daily reference evapotranspiration was calculated using the P-M equation. Information on crop growth and development from 1991 to 2013, including planting and harvesting dates and crop heights, was sourced from national agro-meteorological stations (https://data.cma.cn/) (Fig. 1). In the absence of pertinent data, the information for the period 2014–2019 has been substituted with the average value for the 2010–2013 interval. Soil data, specifically available water capacity (AWC) at a resolution of 250 m, was sourced from SoilGrids (https://www.isric.org/explore/soilgrids). Crop parameters such as crop depletion fraction and rooting depth were referenced from Allen et al.26. The total available soil water capacity was then calculated by multiplying the AWC and crop-specific rooting depth. Standard crop coefficients (\({K}_{c}\)) adjusted for China’s climatic conditions were derived from Li et al.27, based on FAO recommendations. The proportion of each development stage (initial, crop development, mid-season, and late season) of various crops to the whole growing period was derived from Fisher et al.28.

The second section of the data pertains to result validation and includes information such as crop-specific harvested area from the SPAM2010 dataset29 (https://mapspam.info/data/), which estimates crop harvested areas for 42 crops in 2010 with a spatial resolution of 5′ based on the Spatial Production Allocation Model (SPAM). Historical data on crop-harvested areas in 31 provinces in mainland China from 1991 to 2019 were obtained from the National Bureau of Statistics30 (https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/ndsj/). Information on total agricultural water use, the proportion of agricultural irrigation to total water use, and irrigation project efficiency for 31 provinces from 2000 to 2019 were sourced from the China Water Resources Bulletin31 (https://mwr.gjzwfw.gov.cn/). Data on consumptive blue water use at the field scale for crops were collected from various sources including the CERN (https://www.nesdc.org.cn/) and literature32,33,34 (Table 1). The city-level reported irrigation water and irrigated area for wheat, maize, and rice from 2005–2013 were obtained from Zhou et al.19. All raster data mentioned above was resampled to a consistent 1 km resolution for analysis.

Estimating of crop blue and green water use

The daily potential evapotranspiration for a specific crop is defined as the amount of evapotranspiration occurring during the crop’s growth period, regardless of any constraints posed by limited water availability. The primary factors influencing this quantity are the crop type and the growth stage of the crop being evaluated. Daily potential evapotranspiration for crop-specific can be calculated as follows:

where \({{PET}}_{t,i}\) (mm) is the potential evapotranspiration of crop \(i\) on day \(t\). \({K}_{c,t,i}\) is the crop coefficients of crop \(i\) on day \(t\). \({{ET}}_{0,t}\) (mm) is the reference evapotranspiration on day \(t\), which is calculated using the P-M equation.

For the \({K}_{c}\), the standard values for different development stages are taken from Li et al.27, which were adjusted based on the \({K}_{c}\) provided by FAO and the specific conditions in China. The standard \({K}_{c}\) values are not universally applicable across China, as they indicate results for climatic conditions with air humidity of approximately 45%, wind speed of approximately 2 m s−1, sufficient water supply, effective management, normal growth, and large areas aiming for high yields. Consequently, the crop coefficients were adjusted to reflect the actual climatic conditions and management conditions at each meteorological station. The \({K}_{c}\) of each meteorological station is modified by the following formula:

where \({K}_{<mml:mpadded xmlns:xlink="http://www.w3.org/1999/xlink" lspace="-1pt">c</mml:mpadded>\left({tab}\right)<mml:mpadded xmlns:xlink="http://www.w3.org/1999/xlink" lspace="-1pt">,i</mml:mpadded>}\) is the standard \({K}_{c}\) of crop \(i\). \({\mu }_{2}\) (m s−1) is the average wind speed at a height of 2 m at different growth stage. \({{RHU}}_{\min }\) (%) is the average minimum relative humidity at different growth stage. \({h}_{i}\) (m) is the average height of the crop \(i\) at different growth stage.

The actual evapotranspiration of crops is computed as:

where \(A{{ET}}_{t,i}\) (mm) is the actual evapotranspiration of crop \(i\) on day \(t\). \({K}_{s,t,i}\) is a dimensionless transpiration reduction factor of crop \(i\) on day \(t\) that is calculated based on a daily function of the actual and maximum soil moisture in the root zone. The equation is as follows:

where \({S}_{t,i}\) is the actual soil moisture content, and the \({S}_{\max }\) is the maximum available soil water in the effective root zone, which is computed by multiplying the available water capacity by crop rooting depth, as in Allen et al.26. \({p}_{t,i}\) is the fraction of \({S}_{\max }\) that crop \(i\) can extract from the root zone without suffering water stress, and is calculated as follows:

where \({P}_{{std},i}\) is the depletion fraction of crop \(i\) derived from Allen et al.26.

The \({S}_{t,i}\) is simulated by performing soil water balances, and the equation is expressed in the following form:

where \({S}_{t-1,i}\) is the actual soil moisture content on day \(t-1\). \(\triangle t\) is equal to 1. \({P}_{{eff},t}\) (mm) is the effective precipitation on day \(t\), which is calculated using the U.S. Department of Agriculture Soil Conservation Method35,36:

where \({\Pr e}_{t}\) is the precipitation on day \(t\). \({I}_{t,i}\) (mm) symbolizes the supplemental irrigation water applied on day \(t\) for irrigated crops exclusively. Lastly, \({R}_{t,i}\) (mm) signifies the runoff volume derived using the specified formula for the day \(t\).

where \(\gamma \) represents the parameter related to crop management conditions. In irrigated areas, the value is set to 3, while in rainfed areas, it is set to 221.

The preceding steps enable the calculation of the actual evapotranspiration (\(A{{ET}}_{t,i}\)) for each crop on a daily basis under water stress, which represents the green water use (\({{GWU}}_{t,i}\)). Blue water use (\({{BWU}}_{t,i}\)) is characterized by the difference between the potential evapotranspiration of crops (\({{PET}}_{t,i}\)) without water stress and the \(A{{ET}}_{t,i}\), and was only considered for irrigated areas. Subsequently, the total amount of BWU and GWU for each crop’s growth are determined by summing their individual values across every day during the growing season.

where \({{GWU}}_{i}\) (mm yr−1) and \({{BWU}}_{i}\) (mm yr−1) are the green water use and blue water use of crop \(i\). \(n\) indicates the number of days during the growing period of the crops.

Spatialization

A random forest (RF) model was developed to generate spatial predictions of crop blue and green water use at a high spatiotemporal resolution. Compared with the traditional grid-based dynamic water balance model, the proposed method effectively mitigates cross-layer propagation errors that can arise from integrating multiple grid data source, especially when large amounts of climate data with high temporal resolution (e.g., daily scale) are used in this model. In addition, as far as we know, the directly estimating spatially the blue and green water use is further limited by the fact that some climate data products with high spatial resolution have not yet been released. Therefore, we combined site-scale simulation with RF-based spatial prediction to simulate crop blue and green water requirements. The RF model, a form of binary decision rule model that incorporates machine learning technology, has been consistently validated in numerous studies as an effective tool for spatial prediction. In this study, blue and green water use were defined as the dependent variables. We selected several environmental variables, including temperature, precipitation, potential evapotranspiration, available water capacity (AWC), digital elevation model (DEM), and soil components such as sand, silt, clay, and soil type. These variables were analysed using RF modeling with 10-fold cross-validation. The model was set up with 1500 decision trees, and each node in the trees used three variables. The dataset, comprising records of blue and green water use, was split into ten equal subsets. Seven of these subsets were employed to train the model, while the remaining subsets were used to validate its accuracy. The model’s performance was evaluated using metrics such as the coefficient of determination (R²), root mean square error (RMSE), and normalized root mean square error (NRMSE). Consequently, it is now possible to generate detailed estimates of blue and green water use for 15 distinct crops at a spatial resolution of 1 km.

Data Records

The dataset is available at Figshare37. We provide annual blue and green water for irrigated crops and green water for rainfed crops with a 1 km resolution in China from 1991 to 2019. The datasets are provided in the format of NetCDF4, with a spatial reference system of EPSG:4214 (Beijing1954). All the maps can be visualized in ArcMap. Specific datasets detailing the blue and green water use for each crop are available in the provided link (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25980358)37.

Technical Validation

The accuracy of our simulation results was evaluated through three methods, including site-scale validation with measured data at field stations, comparison with statistics, and intercomparison with existing data products. In addition, we compared the annual reference evapotranspiration with the existing datasets and verified the accuracy of the RF model.

Comparison with measured data at field stations

To validate the accuracy of our model, we compared its output with the locally measured values across several crops and sites sourced from the CERN and existing literature (Fig. 3). Firstly, we compared the simulated blue water use of seven crops with the measured results. The findings revealed a strong consistency with an R2 of 0.95 and RMSE of 47.55 mm when the intercept was set to 0 (Fig. 3a). The linear regression line (y = 0.9764x) closely aligns with the 1:1 line. Subsequently, we conducted a comparative analysis of evapotranspiration under various cropping systems (Fig. 3b–f). Due to variations in the geographical positioning of the field stations and meteorological stations used in this study, the daily evapotranspiration obtained from the field stations was juxtaposed with the simulated data derived from nearby meteorological stations. The comparative assessment revealed that while there were disparities between the simulated and observed values of crop evapotranspiration, the overall trends exhibited substantial consistency. The noted differences between the datasets could be attributed to the distinct geographical settings of the respective stations. Collectively, these results indicate the reliability and feasibility of estimating crop water use based on the model proposed in this study.

Comparison of crop blue water use (BWU) and evapotranspiration between measured data at field stations and corresponding values in this study. (a) Scatter plots of simulated crop BWU and measured BWU for 7 crops. Scatter plots of simulated evapotranspiration and measured evapotranspiration for the cropping system in (b) winter wheat-summer maize, (c) spring maize, (d) double rice, (e) winter wheat-late rice, and (f) cotton. The measured data at field stations were obtained from the CERN and existing literature32,33,34.

Comparison with statistical data

Statistical data typically provides the total amount of water use (km3 yr−1). Therefore, the simulated crop blue water use (mm yr−1) and crop harvested area (ha) data were initially combined to calculate the total blue water use (TBWU) of crops. However, the traditional harvested area is available at the provincial scale provided by the National Bureau of Statistics and is therefore unable to capture the spatial heterogeneity of agricultural systems at the grid cells. To address this limitation, we used the SPAM2010 dataset to conduct downscaling research. Here, we assumed that the proportion of each crop harvested area on each grid cell to the total harvested area of each crop in the province remain constant based on the SPAM2010. Then the harvested area of province-level statistics over the 1991–2019 period for each province and crop is multiplied by the above fixed proportion, and SPAM2010 harvested area for each grid cell is adjusted to 1991–2019.

Subsequently, a comparative analysis of TBWU was conducted at the provincial level for all crops and at the city level for wheat, maize, and rice, respectively. According to the China Water Resources Bulletin, we collected the total agricultural water use, the proportion of agricultural irrigation to agricultural water use, and the irrigation project efficiency for 31 provinces in mainland China from 2000 to 2019. Notably, for the irrigation project efficiency, except for the provinces in the Haihe River Basin and Guangdong, which are 80% and 45% respectively, the rest of the provinces adhered to the national average38. These data were then multiplied to obtain the total amount of water used for agricultural irrigation in each province. The results highlighted a strong correlation between simulated and statistical values at the provincial level, with an R2 of 0.77, a slope of the fitted line of 0.92, and an RMSE of 2.79 km3 yr−1 (Fig. 4a). Despite the overall agreement, certain provinces exhibited significant discrepancies between simulated TBWU and statistical TBWU data. In our simulations, we assumed that irrigation water is always available when the irrigation infrastructure is present. This assumption led to an overestimation of TBWU in regions with inadequate irrigation facilities, such as Hebei Province, Shandong Province, and Henan Province in the North China Plain, where farmers typically utilize less water for irrigation than required by crops38. Additionally, we omitted considerations for water-intensive cropping systems like tea, fruits, and vegetables due to the absence of observational data from national agro-meteorological stations during crop growth, potentially resulting in an underestimation of TBWU in certain provinces.

Comparison of total blue water use (TBWU) between statistics and corresponding values in this study. (a) Scatter plots of simulated average TBWU and corresponding statistical BWU for 31 provinces from 1991–2019. (b) Comparison of TBWU simulated by this study, Chiarelli et al.22, Mialyk et al.23, and Wang et al.25 with statistical data for 31 provinces in 2016. Box plots of RMSE (c), NRMSE (d), MAE (e), and R2 (f) for rice, wheat, and maize from 2005–2013 at the city scale compared with Zhou et al.19.

The city-level reported BWU and irrigated area for wheat, maize, and rice during the 2005–2013 period were obtained from Zhou et al.19. We then calculated the TBWU for three crops and compared our results with theirs. The analysis showed that wheat exhibited the highest estimation accuracy with an R2 of 0.68 (0.61–0.70), followed by rice (0.61–0.71) and maize (0.40–0.57) (Fig. 4c–f). Given the higher irrigation demands of rice cultivation, the RMSE, NRMSE, and MAE were higher, which were elevated at 0.32 km3 yr−1, 0.12 km3 yr−1, and 0.18 km3 yr−1, respectively. For wheat, the corresponding values were 0.12 km3 yr−1, 0.09 km3 yr−1 and 0.06 km3 yr−1, while maize recorded RMSE, NRMSE, and MAE of 0.13 km3 yr−1, 0.08 km3 yr−1 and 0.06 km3 yr−1, respectively. All of these results were close to the reported accuracies by Bo et al.39.

Comparison with existing datasets

For the maps of the year 2016, we compared our simulation results with three existing grid datasets that were widely used around the world. Overall, the blue water use of irrigated crops in this study exhibited higher values than those reported by Chiarelli et al.22 and Wang et al.25, but lower than the findings of Mialyk et al.23 (Table S1). This phenomenon may be attributed to the differences in crop planting dates. Mialyk et al.’s crop calendar involve early planting, which generally extends the growing period and potentially increases total water requirements due to higher evapotranspiration during that time26. When considering the harvested area of irrigated crops, the TBWU in 2016 aligned more closely with statistical data, offering a more accurate representation than the three existing data products (Fig. 4b). Overall, it is more consistent with the results of Wang et al.25. Our study revealed relatively lower green water use for both irrigated and rainfed crops compared to the datasets, showing more similarity to the results of Mialyk et al.23, particularly for maize and potatoes. A potential reason for this discrepancy may be attributed to the use of an updated crop calendar in the study of Mialyk et al.23, a composite data product that integrates a multitude of observational data sources. While Chiarelli et al.22 used crop calendars from around 2000. In addition, reference evapotranspiration was used as the basis for quantifying crop water use. Both our study and Mialyk et al.23 calculated the daily values by combining daily meteorological data with the P-M equation, while Chiarelli et al.22 obtained daily reference evapotranspiration by dividing the monthly reference evapotranspiration products by the number of days in the corresponding month. From the perspective of spatial correlation, our study exhibited a higher correlation with Chiarelli et al.22 and Wang et al.25, particularly about the blue water use of irrigated crops. This is primarily because we employed the methodology of integrating the soil water balance model and the crop coefficient, whereas Mialyk et al.23 estimated crop water use by the process-based grid crop models.

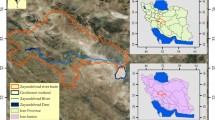

Comparison with remote sensing data

In a recent study, Zhang et al.24 estimated the global irrigation water use by the Integration of multiple satellite observations. However, the simulation results of Zhang et al.24 for Xinjiang and Northeast China exhibited a discernible underestimation24,40. This may be attributed to the fact that the irrigated areas used in the study are static rather than dynamic, which may lead to an underestimation of the total amount of irrigation water required in areas with rapid irrigation expansion24,41. Therefore, a comparison was conducted between the simulated crop blue water use and the datasets from the remaining 27 provinces. The results demonstrated a robust correlation at the provincial scale, with an R2 of 0.9, a slope of the fitted line of 0.85, and an RMSE of 2.76 km3 yr−1 (Fig. S2).

The validation of the reference evapotranspiration

Two publicly available monthly reference evapotranspiration datasets at grid scale were collected42,43 and then calculated the corresponding annual values. Subsequently, the annual reference evapotranspiration data for the stations in this study were then extracted and compared with these datasets. The findings of this study were in good agreement with the dataset, especially the comparison with the Climate Research Unit Time Series (CRU TS) v4.01 datasets43 with an R2 of 0.99 and RMSE of 61.18 mm when the intercept was set to 0 (Fig. 5a). The correlation between this study and Peng et al.42 was relatively weak, with an R2 of 0.98 and RMSE of 172.11 mm. This is mainly due to differences in calculation methods. Both our study and the CRU TS dataset utilized the P-M equation to calculate reference evapotranspiration, whereas Peng et al.42 relied on the Hargreaves’ method. Despite the weaker correlation with Peng et al.42, the strong agreement with the CRU TS dataset underscores the reliability of our methodology in assessing annual reference evapotranspiration data at the grid scale.

Accuracy validation of random forest model

In this study, we conducted calculations of crop blue and green water use at each station (Fig. S1) and generated a spatial map of crop water use using an RF model from 1991 to 2019. Subsequently, the model’s performance was assessed yearly using 10-fold cross-validation. This process is repeated 30 times per year for each crop, and the resulting data are averaged to produce the values presented in the Table 2. The results highlighted the optimal performance of the model in estimating blue water use for irrigated crops, with R2, RMSE, and NRMSE of 0.68, 68.17 mm, and 8.07%, respectively, especially for the winter wheat (R2 = 0.78), potatoes (R2 = 0.85) and sugar beet (R2 = 0.78). For the green water use, the simulation of irrigated crops revealed a superior efficacy, with R2, RMSE, and NRMSE of 0.64, 29.49 mm, and 10.93%, respectively, especially for the single rice (R2 = 0.78), and sugar beet (R2 = 0.80). The accuracy for rainfed crops was slightly lower at 0.60, 26.83 mm, and 11.24%, respectively. Lower accuracy was observed for crops such as sugar cane, and rapeseed, etc., primarily due to the limited number of stations dedicated to monitoring these specific crops.

Spatial distribution

Overall, the blue water use of various crops demonstrated an increasing trend form south to north and from east to west (Fig. 6). Crops such as rice, wheat, sugar cane, cotton and potato have relatively high blue water requirements, whereas crops such as soybean, groundnut and maize have relatively low blue water demand. In addition, the blue water use in northern China is predominantly increasing from 1991 to 2019, particularly in the North China Plain and the northwest inland regions. The decline in this indicator is primarily concentrated in southern China, especially in the provinces along the coast of China (Fig. S3). These findings are in accordance with those previously reported by Yin et al.40. As for green water use, its spatial distribution pattern and change trend are opposite to that of blue water use. Additionally, rainfed crops demonstrated a higher green water use compared to those that were irrigated (Figs. S4–S7).

Uncertainties and limitations

This study leverages localized input parameters such as meteorological data, crop coefficients, and crop growth periods to generate maps of blue and green water use for 15 crops in China using soil water balance models combined with a random forest model. Despite the comprehensive approach, the study acknowledges potential uncertainties that could impact the accuracy of the final water use maps. To assess the uncertainties associated with crop blue and green water use, the study focuses on variations in \({K}_{c}\) values and crop calendars. \({K}_{c}\) values adopted in the research of Zhuo et al.44, allowing for a ± 15% variability for each crop. Additionally, variations in crop calendars were explored by shifting planting dates within ± 15 days while maintaining the overall crop growth duration constant. The results indicated that changes in \({K}_{c}\) values and crop calendars lead to modest fluctuations in green water use (within −9.19% to 9.12%), except for specific crops like early rice, potato, and winter rapeseed (Table 3). Conversely, crop blue water use demonstrated more significant variations ranging from −38.71% to 44.34%, aligning with previous research findings22,44.

In addition to quantifying uncertainty, some limitations in this study also should be noted. Firstly, it should be noted that the study did not consider all crop types in China, such as tea, fruits, vegetables, tobacco, etc. Secondly, due to data limitations, planting and harvesting dates for crop-specific considerations post-2013 were approximated using average data from 2011 to 2013. Furthermore, the deep percolation is not considered in the model, as it is challenging to quantify and separate from ET45. Moreover, the study only used an RF model to produce maps of crop blue and green water use, benefiting from the model’s robustness in estimating crop water requirements compared with other models39. Future research could explore integrating additional environmental factors using models like Support Vector Machines (SVM), Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), High Accuracy Surface Modelling (HASM), among others, to enhance spatial predictions of crop water use. Despite these limitations, the study, when augmented with more localized parameters, offers high-resolution data on blue and green water use for a wide range of crops in China. This dataset is crucial for safeguarding China’s water resources and warrants further exploration and refinement in future studies.

Usage Notes

The 1 km resolution agricultural water consumption dataset generated in this study over the past 30 years serves as crucial data support for agricultural water resources management and ensuring the stability of the agricultural system in China. Researchers can utilize this dataset to analyse crop water consumption patterns, optimize irrigation management strategies, and evaluate water resource utilization efficiency. Government agencies can utilize this dataset to develop irrigation policies, strategize agricultural water resource allocation, advocate for sustainable agricultural methods, and manage water resources efficiently to boost agricultural productivity and safeguard national water resource security. Nevertheless, it is important to note that users should be aware of certain issues when working with this dataset. (1) The blue water use of crops as modeled by us does not correspond precisely to the actual irrigation water use of crops. Crop blue water use represents the water required for irrigation when there is sufficient and functional irrigation infrastructure, indicating an irrigation potential. In regions with insufficient irrigation infrastructure, this can result in an overestimation of the total amount of irrigation water. (2) This study exhibits a degree of error propagation. Initially, due to the discrepancy in spatial locations between meteorological and agro-meteorological stations, we obtained data on crop growth and development from the latter and subsequently mapped it onto Thiessen polygons. Subsequently, we extracted data on crop calendars and crop heights corresponding to each meteorological station. While we anticipate that changes in crop calendars do not significantly impact our estimations of crop water use for most crops (Table 3), such considerations are crucial for research aiming to apply our methodology over extended periods.

Code availability

R code for calculating crop water use is freely available from https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.2598035837.

References

Damerau, K. et al. India has natural resource capacity to achieve nutrition security, reduce health risks and improve environmental sustainability. Nature Food 1, 631–639 (2020).

Davis, K. F., Rulli, M. C., Seveso, A. & D’Odorico, P. Increased food production and reduced water use through optimized crop distribution. Nature Geoscience 10, 919–924 (2017).

Mekonnen, M. M. & Hoekstra, A. Y. A global and high-resolution assessment of the green, blue and grey water footprint of wheat. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 14, 1259–1276 (2010).

Mekonnen, M. M. & Hoekstra, A. Y. The green, blue and grey water footprint of crops and derived crop products. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 15, 1577–1600 (2011).

Huang, Z. et al. Global agricultural green and blue water consumption under future climate and land use changes. Journal of Hydrology 574, 242–256 (2019).

Springmann, M. et al. Options for keeping the food system within environmental limits. Nature 562, 519–525 (2018).

Wang, M. L. & Shi, W. J. Research progress in assessment and strategies for sustainable food system within planetary boundaries. Science China Earth Sciences 67, 375–386 (2024).

Cao, X., Ren, J., Wu, M., Guo, X. & Wang, W. Assessing agricultural water use effect of China based on water footprint framework. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering 34, 1–8 (2018).

The State Council of China. China has become the world’s largest irrigation country. https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2022-11/06/content_5724969.htm (2022).

Liang, H., Hu, K., Batchelor, W. D., Qi, Z. & Li, B. An integrated soil-crop system model for water and nitrogen management in North China. Scientific Reports 6, 25755 (2016).

Long, D. et al. South-to-North Water Diversion stabilizing Beijing’s groundwater levels. Nature Communications 11, 3665 (2020).

Hu, Y. et al. Food production in China requires intensified measures to be consistent with national and provincial environmental boundaries. Nature Food 1, 572–582 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. Characterization of soil salinization and its driving factors in a typical irrigation area of Northwest China. Science of The Total Environment 837, 155808 (2022).

Shi, W. et al. Wheat redistribution in Huang-Huai-Hai, China, could reduce groundwater depletion and environmental footprints without compromising production. Communications Earth & Environment 5, 380 (2024).

Wang, S. et al. Urbanization can benefit agricultural production with large-scale farming in China. Nature Food 2, 183–191 (2021).

Huang, F. et al. Current situation and future security of agricultural water resources in North China (in Chinese). Strategic Study of CAE 21, 28–37 (2019).

Zhao, H. et al. China’s future food demand and its implications for trade and environment. Nature Sustainability 4, 1042–1051 (2021).

Zhang, C., Dong, J. & Ge, Q. Mapping 20 years of irrigated croplands in China using MODIS and statistics and existing irrigation products. Scientific Data 9, 407 (2022).

Zhou, F. et al. Deceleration of China’s human water use and its key drivers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 117, 7702–7711 (2020).

Li, X. R., Jiang, W. L. & Duan, D. D. Spatio-temporal analysis of irrigation water use coefficients in China. Journal of Environmental Management 262, 110242 (2020).

Siebert, S. & Döll, P. Quantifying blue and green virtual water contents in global crop production as well as potential production losses without irrigation. Journal of Hydrology 384, 198–217 (2010).

Chiarelli, D. D. et al. The green and blue crop water requirement WATNEEDS model and its global gridded outputs. Scientific Data 7, 273 (2020).

Mialyk, O. et al. Water footprints and crop water use of 175 individual crops for 1990–2019 simulated with a global crop model. Scientific Data 11, 206 (2024).

Zhang, K., Li, X., Zheng, D., Zhang, L. & Zhu, G. Estimation of Global Irrigation Water Use by the Integration of Multiple Satellite Observations. Water Resources Research 58, e2021WR030031 (2022).

Wang, W. et al. A gridded dataset of consumptive water footprints, evaporation, transpiration, and associated benchmarks related to crop production in China during 2000–2018. Earth System Science Data 15, 4803–4827 (2023).

Allan, R. G., Pereira, L. S., Rase, D. & Smith, M. Crop evapotranspiration: Guidelines for computing crop water requirements-FAO Irrigation and drainage paper 56. (FAO, Rome, 1998).

Li, X. Agricultural irrigation water requirement and its regional characteristic in China (in Chinese). Tsinghua University (2006).

Fischer, G. et al. Global Agro-Ecological Zones v4 – Model documentation. (FAO, Rome, 2021).

Yu, Q. et al. A cultivated planet in 2010 – Part 2: The global gridded agricultural-production maps. Earth System Science Data 12, 3545–3572 (2020).

National Bureau of Statistics. China Statistical Yearbook 2020 (China Statistics Press, 2020).

Ministry of Water Resources of China. China Water Resources Bulletin (China Water & Power Press, 2020).

Gao, Y. et al. Winter wheat with subsurface drip irrigation (SDI): Crop coefficients, water-use estimates, and effects of SDI on grain yield and water use efficiency. Agricultural Water Management 146, 1–10 (2014).

Liu, H. J., Yu, L. P., Luo, Y., Wang, X. P. & Huang, G. H. Responses of winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) evapotranspiration and yield to sprinkler irrigation regimes. Agricultural Water Management 98, 483–492 (2011).

Zhou, S. Q. et al. Evapotranspiration of a drip-irrigated, film-mulched cotton field in northern Xinjiang, China. Hydrological Processes. 26, 1169–1178 (2012).

Döll, P. & Siebert, S. Global modeling of irrigation water requirements. Water Resources Research 38, 1037 (2002).

Martin, S. & Land, F. Cropwat: a computer program for irrigation planning and management. (FAO, Rome, 1992)

Wang, M. & Shi, W. Data underlying the publication: The annual dynamic dataset of high-resolution crop water use in China from 1991 to 2019. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25980358.v1 (2024).

Liu, J. & Yang, H. Spatially explicit assessment of global consumptive water uses in cropland: Green and blue water. Journal of Hydrology 384, 187–197 (2010).

Bo, Y. et al. Hybrid theory‐guided data driven framework for calculating irrigation water use of three staple cereal crops in China. Water Resources Research 60, e2023WR035234 (2024).

Yin, L. et al. Irrigation water consumption of irrigated cropland and its dominant factor in China from 1982 to 2015. Advances in Water Resources. 143, 103661 (2020).

Zhang, C., Dong, J. & Ge, Q. IrriMap_CN: Annual irrigation maps across China in 2000–2019 based on satellite observations, environmental variables, and machine learning. Remote Sensing of Environment. 280, 113184 (2022).

Peng, S. 1 km monthly potential evapotranspiration dataset in China (1901–2022). Center National Tibetan Plateau Data https://doi.org/10.11866/db.loess.2021.001 (2022).

Harris, I., Osborn, T. J., Jones, P. & Lister, D. Version 4 of the CRU TS monthly high-resolution gridded multivariate climate dataset. Scientific Data 7, 109 (2020).

Zhuo, L., Mekonnen, M. M. & Hoekstra, A. Y. Sensitivity and uncertainty in crop water footprint accounting: a case study for the Yellow River basin. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 18, 2219–2234 (2014).

Shi, P., Gai, H. & Li, Z. Partitioned soil water balance and its link with water uptake strategy under apple trees in the Loess‐Covered region. Water Resources Research 59, e2022WR032670 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA0440405), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFB3903504), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (72221002 and 42330707).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Minglei Wang: Data curation, methodology, software, visualization, validation, writing-original draft. WenjiaoShi: Resources, methodology, writing-review & editing, funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, M., Shi, W. The annual dynamic dataset of high-resolution crop water use in China from 1991 to 2019. Sci Data 11, 1373 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-04185-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-04185-0

This article is cited by

-

High-resolution water footprints of major crops in China from cities to grids

Scientific Reports (2025)