Abstract

Ochetobius elongatus, a critically endangered species found in the Yangtze River was the subject of our study in which we leveraged PacBio and Hi-C data to assemble a chromosome-scale genome. This assembly comprises 24 pseudo-chromosomes, yielding a genome size of 883.1 Mb with a scaffold N50 length of 35.1 Mb, indicative of a highly contiguous assembly. A BUSCO assessment ascertained the comprehensiveness of the genome at 98.3%. Annotation efforts identified 28,674 putative protein-coding genes, with 44.63% of the assembled genome annotated as repetitive sequences. Collinearity analysis between O. elongatus and two other species from the family Xenocyprididae revealed high collinearity, indicating good assembly quality of O. elongatus The completion of the O. elongatus genome assembly in this study signifies a critical advancement for its conservation, enabling deeper insights into its genetic diversity and facilitating the development of targeted preservation strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

The Yangtze River Basin, ranked as the world’s third-largest river basin, spans an extensive area of 1,800,000 square kilometers and is home to over 400 species of fish. However, due to intensive development, there has been a notable decline in biodiversity1. Surveys conducted throughout the basin between 2017 and 2018 identified 332 species of fish, yet 140 historically recorded species were not found, with most considered to be critically endangered2. For example, the Yangtze River dolphin (Lipotes vexillifer) saw its population plummet from approximately 400 individuals in the 1980s to fewer than 50 by the end of the 20th century, with no sightings reported after 20061,3, and it is now considered functionally extinct4. To restore the ecosystem, a ten-year fishing ban was implemented in the Yangtze River. Preliminary results indicate an improvement in fishery resources, with 11 native species that had long disappeared reappearing in the Chishui River, a tributary of the Yangtze5.

O. elongatus was once a significant freshwater economic fish in China, widely distributed in the Yangtze River6 (Fig. 1). However, due to environmental degradation and human activities, the population of this species has rapidly declined. Based on the assessment criteria A2acd from the IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria, which indicates a significant reduction in population over the past decade, the species was observed to have declined by at least 80% according to direct observations, a decrease in extent of occurrence, area of occupancy, or habitat quality, and actual or potential levels of exploitation. Consequently, the species was listed as Critically Endangered (CR) in the Red List of China’s Vertebrates of Endangered Animals in 20167,8,9. Studies in 2018 indicated that the wild population of O. elongatus was in a state of decline7. Following the implementation of the ten-year fishing ban in the Yangtze River, in December 2020, seven individuals of O. elongatus were discovered in the Gong’an section of the Yangtze River. This marked the third time the species had been observed since June 2017 and November 2020, and it was the first instance in recent years of multiple individuals being recorded (https://www.cafs.ac.cn/info/1024/36845.htm). The reappearance of O. elongatus provides an opportunity for conservation. Despite the application of conservation genetics and genomics in the protection of several endangered species within the Yangtze River Basin—such as the two subspecies of Neophocaena asiaeorientalis (sunameri10 and asiorientalis11), the endangered species Gobiocypris rarus12, and the vulnerable species Leptobotia elongata13—all of which have had their genomes sequenced and assembled, the critically endangered O. elongatus, also inhabiting the Yangtze River Basin, has yet to have its genome assembled. The assembly of a genome is crucial for understanding the genetic diversity, identifying unique adaptations, and developing effective conservation strategies for endangered species. The lack of a genome assembly for O. elongatus represents a significant obstacle to its conservation efforts.

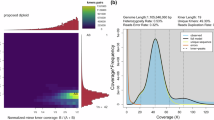

In this study, we assembled the chromosome-scale genome sequence of O. elongatus utilizing a combination of PacBio long reads and Hi-C technology (Table 1). The initial assembly spanned 898.4 Mb across 144 contigs with a contig N50 of 24.8 Mb (Table 2). Following redundancy removal and Hi-C scaffolding, 99.83% of the assembly, totaling 881.6 Mb, was anchored to 24 pseudo-chromosomes, yielding a scaffold N50 of 35.1 Mb with 40 scaffolds (Fig. 2, Tables 2, 3). Upon conducting BUSCO analysis with the Actinopterygii_odb10 database, the results included 3,581 (98.3%) complete BUSCOs, 3,536 (97.1%) single-copy BUSCOs, 45 (1.2%) duplicated BUSCOs, 21 (0.6%) fragmented BUSCOs, and 38 (1.1%) missing BUSCOs (Table 4). Annotation revealed 394.1 Mb of repetitive sequences (Fig. 3, Table 5), mainly composed of DNA transposons (221.10 Mb, 25.04%). A total of 28,674 protein-coding genes were predicted using a combined approach of homology-based, RNA-Seq-assisted, ab initio methods, with 28,637 genes (99.87%) annotated (Table 6). Collinearity analysis between O. elongatus and two other species from the family Xenocyprididae revealed high collinearity, indicating good assembly quality of O. elongatus (Fig. 4). The accomplishment of assembling the O. elongatus genome in this study represents a pivotal step forward in conservation efforts, providing a more profound understanding of its genetic diversity. This genomic information serves as a cornerstone for the formulation of precise and effective preservation strategies.

Characteristics of the O. elongatus genome. (a) Hi-C intra-chromosomal contact map of the O. elongatus genome assembly. (b) Genomic synteny circos plot between zebrafish (Danio rerio) and O. elongatus. (1) O. elongatus chromosomes at 100 kb scale; (2) GC content; (3) coding sequences drawn in a 100 kb sliding window with a 100 kb step.

Methods

Sample collection and sequencing

A healthy individual of O. elongatus was collected from the Jiujiang section of the Yangtze River, Jiangxi Province, China, on March 21, 2024. DNA was extracted from their muscle tissue samples for long-read Single Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing, and Hi-C sequencing. For RNA sequencing, total RNA was prepared by pooling RNA extracted from ten distinct tissues (muscle, gill, liver, brain, heart, caudal fin, gut, gonad, skin). All samples were rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen and subsequently stored at −80 °C to ensure preservation of integrity.

The processes for DNA extraction, library preparation, and sequencing were executed by Nextomics Biosciences (Wuhan, China), strictly adhering to the protocols provided by the manufacturers. Genomic DNA of high molecular weight was obtained from muscle samples, and only DNA of high quality was employed for the construction of sequencing libraries and subsequent high-throughput sequencing.

For PacBio sequencing, SMRTbell libraries were constructed using a 20-kilobase preparation kit according to the standard protocols outlined by Pacific Biosciences (CA, USA)14. The library preparation process included steps such as DNA shearing, end-repair, and ligation with hairpin adapters to generate circular templates compatible with SMRT sequencing technology. Sequencing was conducted on the PacBio Revio platform using Circular Consensus Sequencing (CCS) mode, in line with the manufacturer’s guidelines. Quality control of the raw data was performed using the ccs software (https://github.com/PacificBiosciences/ccs), with parameters set to “-min-passes 1 -min-rq 0.99 -min-length 100”. Sequencing a single SMRT cell yielded 105.0 Gb of PacBio CCS reads, providing a coverage depth of 118.9×, which was utilized for subsequent genome assembly. The average length of the subreads was 18,447 base pairs (Table 1).

For Hi-C sequencing, freshly collected muscle tissues were stabilized through fixation with 2% formaldehyde to facilitate DNA-protein crosslinking. The preparation of Hi-C libraries involved steps including the digestion of cross-linked DNA, biotin labeling, proximity-based ligation, and DNA purification15. Subsequently, the Hi-C libraries were sequenced on the MGISEQ-2000 platform using 150 bp paired-end reads to capture the spatial interactions between chromosomal regions. This resulted in generating 81.4 Gb of Hi-C data with an average sequencing depth of 92.2× (Table 1).

Total RNA was extracted from ground tissue using TRIzol reagent (Tiangen, Germany) under cryogenic conditions, following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA from muscles, liver, intestine, head kidney, heart, spleen, kidney, gills, brain, and gonads was combined for RNA-Seq on the MGISEQ-2000 platform. This process generated 18.6 Gb of RNA-seq data, which was utilized for comprehensive genome-wide prediction of protein-coding genes (Table 1).

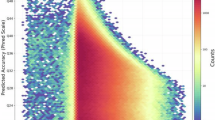

Genome survey and assembly

The de novo genome assembly of a total 105.0 Gb PacBio long-read dataset (Table 1) was performed utilizing Hifiasm v0.16.116. This approach yielded an assembly of 898.4 Mb, comprising 144 contigs with an N50 contig length of 24.8 Mb (Table 2).

After the initial genome assembly, the assembly was further refined using purge_dups v1.2.517 in conjunction with minimap2 v2.2218. Minimap2 was used to align the sequencing reads to the assembled contigs, assessing coverage across different segments and conducting self-alignments to identify repetitive structures. Purge_dups then utilized this alignment information to detect and classify repetitive sequences, differentiating primary assembly components from potential haplotypes, thereby aiding in the removal of redundancies and resolving haplotypes. The final deduplicated genome size was 883.1 Mb, consisting of 90 contigs with an N50 contig length of 24.8 Mb (Table 2).

Subsequently, Hi-C data was utilized to anchor and orient the draft genome contigs into chromosome-scale assemblies. The deduplicated genome assembly was indexed using bwa v0.7.1719 and samtools v1.720. Hi-C reads were aligned to the genome using bwa mem, and the resulting alignment files were processed and sorted with samtools sort. PCR duplicates were removed from the alignments using bammarkduplicates2 in biobambam2 v2.0.8721. Further refinement of the assembly was achieved using yahs v1.122, which leveraged Hi-C data to enhance scaffold ordering and orientation, yielding an updated assembly. Gap and telomere analyses of this assembly were conducted using Pretextmap v0.1.9 (https://github.com/sanger-tol/PretextMap), followed by manual curation with PretextView v0.2.5 (https://github.com/sanger-tol/PretextView), where users adjust the position of sequence fragments based on visualized genomic interaction information. Scaffolds exhibiting strong interaction signals were clustered together, enabling demarcation of chromosomal boundaries.

Ultimately, 99.83% of the initial assembled sequences were anchored onto 24 pseudo-chromosomes, with sizes ranging from 27.61 to 54.33 Mb, resulting in a total genome assembly length of 883.1 Mb, comprised of 40 scaffolds with a scaffold N50 of 35.1 Mb (Fig. 2, Table 3). To evaluate the completeness of the genome, BUSCO version 5.4.723 was utilized with parameters ‘-l actinopterygii_odb10 -g genome’, an assessment of genomic integrity was conducted against the Actinopterygii reference dataset. Of the 3,640 benchmarking sets, 3,581 (98.3%) were identified as complete, indicative of a high-quality genome assembly. The assessment also revealed minor fragmentation with 21 (0.6%) fragmented BUSCOs and 38 (1.1%) missing BUSCOs. Notably, the assembly exhibited exceptional continuity, with inter-sequence gaps accounting for merely 0.001%, affirming a highly contiguous and accurate genomic structure (Table 4).

Repetitive sequence annotation

For the annotation of repetitive sequences, we utilized RepeatMasker v4.1.624 with Dfam database utilizing advanced Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) for known repeats, and with RepBase for a complete family representation. For the identification of detecting species-specific repeats not catalogued in public databases, RepeatModeler v2.0.525 was implemented to construct de novo repeat libraries through iterative clustering and refinement of sequence data. The annotations derived from Dfam, RepBase, and RepeatModeler were then consolidated into a unified dataset, with overlapping annotations merged and redundant entries removed. The outcomes of repetitive sequence annotation are summarized in Table 5, revealing that DNA transposons constitute 25.04%, making them the most prevalent type of repetitive sequence (Fig. 3).

Protein-coding gene prediction and annotation

Gene predictions were conducted through a combination of homology, transcriptome-based prediction and de novo prediction methods.

For homology-based gene prediction, full-genome protein sequences from three Xenocyprididae family species were utilized. Grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella, GCF_019924925.1), Wuchang bream (Megalobrama amblycephala, GCF_018812025.1), and predatory carp (Chanodichthys erythropterus, GCF_024489055.1) genomes were downloaded from GenBank as sources of homologous proteins. To align multi-species homologous protein sequences against the target genome, MMseqs v15-6f45226 was employed, applying a filter criterion of “identity > 0.1, evalue < 1e-3”. Overlapping High Scoring Segment Pairs (HSPs) resulting from alternative splicing were merged, and a stricter filter was applied with “identity > 0.2, evalue < 1e-9, query coverage > 0.3”. To refine the alignment accuracy, genewise v2.4.127, gth v1.7.328, and exonerate v2.2.029 were used to perform precise spliced alignments of matched proteins to their homologous protein sequences, aiding in the prediction of gene structures for each protein region. RNA-Seq datasets from ten tissues were subjected to quality control using Trimmomatic v0.3930 and the trimmed reads were aligned to the reference genome sequence using HISAT2 v2.1.031. Open Reading Frames (ORFs) were predicted from the assembled transcripts with TransDecoder v5.5.032. Additionally, Augustus v3.5.033 was used for de novo prediction of gene structures. The gene predictions from gene predictions were combined to create a non-redundant reference gene set, resulting in a total of 28,674 protein-coding genes (Table 6).

Protein-coding genes were annotated by the aligning genomic sequences against the NT database using Blast v2.13.034 with an e-value threshold set at 1e-10. The predicted protein sequences were further compared against the NR, Uniprot35, GO36, KEGG37, COG38, Pfam39 databases utilizing diamond v2.1.840. Ultimately, 28,637 genes (99.87%) received successful annotations (Table 6).

Colinearity analysis

Genome collinearity analysis and visualizations were performed using the MCScanX41 tool from TBtools v2.09642 with parameters set as follows: e-value was set to 1e-10, and the Number of BlastHits was set to 5. Collinearity analysis between O. elongatus and two other species from the family Xenocyprididae revealed high collinearity, indicating good assembly quality of O. elongatus (Fig. 4).

Data Records

The sequencing dataset and the genome assembly are stored in public databases. The sequencing data used for genome assembly, including PacBio, Hi-C, and RNA-seq, have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information’s (NCBI) Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under BioProject PRJNA116301543. The complete genomic sequence data has been submitted to NCBI GenBank database with the accession number GCA_041950425.144. The results of the genome annotation have been made available in the Figshare database45.

Technical Validation

For DNA intended for library preparation and sequencing, quality and purity were evaluated using 0.75% agarose gel electrophoresis, which showed that the main band size was greater than 23,130 bp. Additionally, purity and concentration were assessed using both a NanoDrop One UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and Qubit Fluorometer (Invitrogen, USA). The concentrations measured by both instruments were greater than 461.0 ng/µL. The NanoDrop results also indicated a 260/280 ratio of 1.87 and a 260/230 ratio of 2.43.

The RNA used for library preparation and sequencing had a concentration greater than 640.0 ng/µL as measured by NanoDrop and Qubit. Its integrity was assessed using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, USA) with Agilent RNA 6000 Nano Kit (Agilent, USA), yielding an RNA Integrity Number (RIN) of 8.8, indicating good integrity.

BLAST v2.13.0 was used to align genomic sequences to the NT database, enabling the identification of protein-coding genes and the assessment of genomic sequence contamination. A stringent 1e-10 e-value cutoff was selected. The analysis confirmed that there were no bacterial or artificial contaminants in our constructed genome.

Code availability

All software used in this study are in the public domain, with parameters being clearly described in Methods. If no detail parameters were mentioned for the software, default parameters were used as suggested by developer.

References

Chen, T., Wang, Y., Gardner, C. & Wu, F. Threats and protection policies of the aquatic biodiversity in the Yangtze River. Journal for Nature Conservation 58, 125931, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnc.2020.125931 (2020).

Zhang, H. et al. Extinction of one of the world’s largest freshwater fishes: Lessons for conserving the endangered Yangtze fauna. Science of the Total Environment 710, 136242, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.136242 (2020).

Zhang, X. et al. The Yangtze River dolphin or baiji (Lipotes vexillifer): population status and conservation issues in the Yangtze River, China. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 13(1), 51–64, https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.547 (2003).

Bin, W., Weiping, W., Haihua, W. & Gang, H. A retrospective analysis on the population viability of the Yangtze river Dolphin or Baiji (Lipotes vexillifer). Indian Journal of Animal Research 56(6), 775–779, https://doi.org/10.18805/ijar.B-1238 (2022).

Liu, F. et al. Changes in fish resources 5 years after implementation of the 10-year fishing ban in the Chishui River, the first river with a complete fishing ban in the Yangtze River Basin. Ecological Processes 12, 51, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-023-00465-6 (2023).

Weitao, C. et al. Genetic structure analysis of Ochetobius elongatus between Yangtze River and Pearl River using multiple loci. South China Fisheries Science 18(6), 19–25, https://doi.org/10.12131/20220007 (2022).

Yang, J., Li, C., Chen, W., Li, Y. & Li, X. Genetic diversity and population demographic history of Ochetobius elongatus in the middle and lower reaches of the Xijiang River. Biodiversity Science 26(12), 1289, https://doi.org/10.17520/biods.2018121 (2018).

Yang, J. et al. Development and characterization of 26 SNP markers in Ochetobius elongatus based on restriction site-associated DNA sequencing (RAD-seq). Conservation genetics resources 12, 53–55, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12686-018-1075-3 (2020).

Jiang, Z. et al. Red list of China’s vertebrates. Biodiversity Science 24(5), 500–551, https://doi.org/10.17520/biods.2016076 (2016).

Yin, D. et al. Telomere-to-telomere gap-free genome assembly of the endangered Yangtze finless porpoise and East Asian finless porpoise. GigaScience 13, giae067, https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giae067 (2024).

Yuan, Y. et al. Genome sequence of the freshwater Yangtze finless porpoise. Genes 9(4), 213, https://doi.org/10.3390/genes9040213 (2018).

Hu, X. et al. Genomic deciphering of sex determination and unique immune system of a potential model species rare minnow (Gobiocypris rarus). Science Advances 4 8(5), eabl7253, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abl7253 (2022).

Wen, Z. et al. Chromosome-level genome assemblies of vulnerable male and female elongate loach (Leptobotia elongata). Scientific data 11, 924, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03789-w (2024).

Eid, J. et al. Real-Time DNA Sequencing from Single Polymerase Molecules. Science 323, 133–138, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1162986 (2009).

Rao, S. et al. A 3D Map of the Human Genome at Kilobase Resolution Reveals Principles of Chromatin Looping. Cell 159, 1665–1680, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.021 (2014).

Cheng, H., Concepcion, G. T., Feng, X., Zhang, H. & Li, H. Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nature Methods 18, 170–175, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-020-01056-5 (2021).

Guan, D. et al. Identifying and removing haplotypic duplication in primary genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 36(9), 2896–2898, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa025 (2020).

Li, H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 34(18), 3094–3100, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty191 (2018).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324 (2009).

Li, H. et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25(16), 2078–2079, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352 (2009).

Tischler, G. & Leonard, S. biobambam: tools for read pair collation based algorithms on BAM files. Source Code for Biology and Medicine 9, 13, https://doi.org/10.1186/1751-0473-9-13 (2014).

Zhou, C., McCarthy, S. A. & Durbin, R. YaHS: yet another Hi-C scaffolding tool. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 39(1), btac808, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btac808 (2023).

Simao, F. A. et al. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31, 3210–3212, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351 (2015).

Bao, W., Kojima, K. K. & Kohany, O. Repbase Update, a database of repetitive elements in eukaryotic genomes. Mobile DNA 6, 11, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13100-015-0041-9 (2015).

Flynn, J. M. et al. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117(17), 9451–9457, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1921046117 (2020).

Steinegger, M. & Söding, J. MMseqs. 2 enables sensitive protein sequence searching for the analysis of massive data sets. Nature Biotechnology 35, 1026–1028, https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.3988 (2017).

Doerks, T., Copley, R. R., Schultz, J., Ponting, C. P. & Bork, P. Systematic identifcation of novel protein domain families associated with nuclear functions. Genome Research 12, 47–56, https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.203201 (2002).

Gremme, G., Brendel, V., Sparks, M. E. & Kurtz, S. Engineering a software tool for gene structure prediction in higher organisms. Information and Software Technology 47(15), 965–978, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infsof.2005.09.005 (2005).

Slater, G. S. C. & Birney, E. Automated generation of heuristics for biological sequence comparison. BMC Bioinformatics 6, 31, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-6-31 (2005).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30(15), 2114–2120, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170 (2014).

Kim, D., Paggi, J. M., Park, C., Bennett, C. & Salzberg, S. L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nature Biotechnology 37, 907–915, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0201-4 (2019).

Haas, B. et al. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nature protocols 8(8), 1494–1512, https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2013.084 (2013).

Stanke, M. et al. AUGUSTUS: ab initio prediction of alternative transcripts. Nucleic Acids Research 34, W435–439, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkl200 (2006).

McGinnis, S. & Madden, T. BLAST: at the core of a powerful and diverse set of sequence analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Research 32, W20–25, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkh435 (2004).

UniProt Consortium, T. UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Research 46, 2699, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky092 (2018).

Ashburner, M. et al. Gene Ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nature Genetics 25, 25–29, https://doi.org/10.1038/75556 (2000).

Kanehisa, M. et al. Data, information, knowledge and principle: back to metabolism in KEGG. Nucleic Acids Research 42, D199–205, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkt1076 (2014).

Tatusov, R., Galperin, M., Natale, D. & Koonin, E. The COG database: a tool for genome-scale analysis of protein functions and evolution. Nucleic Acids Research 28(1), 33–6, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.1.33 (2000).

Finn, R. et al. Pfam: the protein families database. Nucleic Acids Research 42, D222–30, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkt1223 (2014).

Buchfink, B., Xie, C. & Huson, D. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nature Methods 12, 59–60, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3176 (2015).

Wang, Y. et al. MCScanX: a toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic acids research 40(7), e49–e49, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkr1293 (2012).

Chen, C. et al. TBtools: an integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Molecular plant 13(8), 1194–1202, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molp.2020.06.009 (2020).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive. https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP533749 (2024).

Liang, X. Ochetobius elongatus isolate XLOel202024, whole genome shotgun sequencing project. GenBank. https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc:JBHHFX000000000 (2024).

Liang, X. The genomic annotation-related data for Ochetobius elongatus. figshare. Dataset. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27088858.v1 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by the Jiujiang Academy of Agricultural Sciences, China, and the project ‘Research on Breeding Technology of Candidate Species for Guangdong Modern Marine Ranching’ (Project: 2024-MRB-00-001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jianguo Lu: Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing-review & editing; Chiping Kong: Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Resources, Writing-review & editing; Lekang Li: Resources, Writing-review & editing; Xuanguang Liang: Formal analysis, Data curation, Validation, Visualization, Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing; Jiatong Zhang: Data curation, Writing-review & editing; Qun Xu: Resources, Writing-review & editing; Li Wang: Writing-review & editing; Xiaoping Gao: Resources, Writing-review & editing; Xiangchun Song: Resources; Bao Zhang: Resources, Writing-review & editing; Dan Huang: Resources; Hong Wang: Resources; Xianyong Wang: Resources; Zhen Luo: Resources. Lekang Li and Xuanguang Liang contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, L., Liang, X., Zhang, J. et al. A chromosome-level genome assembly of critically endangered Ochetobius elongatus. Sci Data 11, 1399 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-04223-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-04223-x