Abstract

The field of phenomics is experiencing unprecedented advances thanks to the rapid growth of morphological quantification based on three-dimensional (3D) imaging, online data repositories, team-oriented collaborations, and open data-sharing policies. In line with these progressions, we present an extensive primate phenotypic dataset comprising >6,000 3D scans (media) representing skeletal morphologies of 386 individual specimens covering all hominoid genera (except humans) and other selected primates. The digitized specimens are housed in physical collections at the American Museum of Natural History, the National Museum of Natural History, the Royal Museum for Central Africa (Belgium), the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, and Stony Brook University. Our technical validation indicates that despite the diverse digitizing devices used to produce the scans, the final 3D models (meshes) can be safely combined to collect comparable morphometric data. The entire dataset (and detailed associated metadata) is freely available through MorphoSource. Hence, these data contribute to empowering the future of primate phenomics and providing a roadmap for future digitization and archiving of digital data from other collections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

The early years of genomics research were marked by ground-breaking studies that achieved significant milestones in biological research, especially studies documenting the genomes for model organisms, including (in chronological order) the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae1, the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans2, the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster3, the thale cress Arabidopsis thaliana4, and the house mouse Mus musculus5. For Primates, the 2001 draft sequence of the human genome6 stands out as the first major contribution of the genomic era, a landmark accomplished that was promptly followed by draft genomes of the remaining hominoids (chimpanzees7,8, gorillas9,10, orangutans11, and hylobatids12) and other primate taxa.

By comparison, phenotypic studies incorporating diverse anatomical regions have been more limited and have historically relied primarily on qualitative character matrices (e.g., ref. 13), sometimes including 2D continuous measurements (e.g., ref. 14). More recently, large-scale phenotypic studies based on 3D morphometrics have illustrated the possibilities of using high-resolution phenotypic data for evolutionary studies (e.g., this series in birds, refs. 15,16,17). Such work has been possible thanks to developments in 3D digitization over the last two decades, including faster, more accurate, and more affordable scanning technology. In the case of surface scanners (which are not only affordable but easily portable), the use of this equipment has been accompanied by an increasing shift from the use of linear measurements to form quantification based on 3D digital data (e.g., landmarks collected virtually over a 3D mesh). Whereas researchers used to visit collections carrying only callipers, many now do so with portable structured-light scanners.

Open data sharing is essential to equal advancement in all fields of science. In this aspect, phenomics also lags behind genomics. Geneticists first started to openly share their massive datasets in 1982 with the establishment of GenBank. By contrast, morphologists have been more reluctant to share their data despite evidence that data sharing fosters collaboration, facilitates international research (having a major impact on students, especially in countries with fewer funding opportunities and/or ongoing reductions in existing science budgets), and is crucial for experimental reproducibility18,19,20 However, some large 3D morphological datasets of primates (e.g., ref. 21) and other vertebrates (e.g., ref. 22,23) have been made openly available over the last few years.

The dataset presented here builds on this constructive trend in phenomic data sharing. It results from over a decade of 3D data collection in different museums and research institutions for various projects related to primate evolution, some of which have already produced publications (e.g., refs. 24,25,26,27). Until now, access to selected 3D scans has been limited to on-demand requests from students and other researchers, for whom many collections remain hard to access. However, given the increased volume of such requests and the need to address essential aspects related to the data itself (associated metadata, authorship, and funding recognition)28, we have uploaded and made openly available the total amount of our non-human primate scans through the online public 3D scientific data repository MorphoSource (https://www.morphosource.org/, see Data Records below).

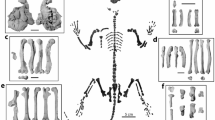

The purpose of this data descriptor paper is to summarize the extensive and unique content of the dataset, as well as to contextualize its creation and provide useful guidelines for its usage. Currently, the dataset introduces 6,192 3D scans (all constituting new MorphoSource “media” deposits), with each single- or multi-file media representing a single surface scan or CT image series of various regions of the primate skeletal phenotype. These media were collected from 386 individual specimens representing 47 genera, mostly non-human hominids and other hominoids, as well as other select anthropoid primates (see taxonomic summaries in Fig. 1 and Table 1). Taxonomic counts are approximate because taxonomic identifications in MorphoSource are integrated with data from external community resources, such as iDigBio (https://www.idigbio.org/) and the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF, https://www.gbif.org/), which are both aggregators of specimen information from natural history collections. As natural history collections and other data sources revise, improve, and update taxonomic identifications for specimens, those changes will be reflected in MorphoSource. These 3D scans were digitized from physical specimens (mostly wild-collected) housed at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH; New York, NY, USA), the National Museum of Natural History (NMNH; Washington, DC, USA), the Royal Museum for Central Africa (RMCA; Tervuren, Belgium), the Cleveland Museum of Natural History (CMNH; Cleveland, OH, USA), and Stony Brook University (SBU; Stony Brook, NY, USA). The number of media associated with each digitized primate specimen ranges from one to >60. All skeletal regions of the body are represented in the dataset, especially hands and feet, for which more scans and more bones per scan are present (Fig. 2). In some cases, media are derived from scans in other MorphoSource projects (e.g., 3D meshes derived from a stack of CT images; 42 crania) or shared with other projects (49 media total). Similarly, we anticipate that other users will produce additional data derived from our media, the trail of which can be readily followed in MorphoSource.

Sample media breakdown by taxonomic group. Waffle plot (a) shows the proportion of media by major primate clades: hominoids (red), cercopithecoids (green), platyrrhines (brown), and non-anthropoid primates (blue). Donut plots (b-e) show a breakdown of these major groups at the family, subfamily, or higher-level ranks. Custom silhouettes represent an orangutan, a baboon, a howler monkey, and a loris, respectively.

Types of media in the dataset. Donut plots showing media sample breakdown by (a) anatomical region, (b) number of media per individual, and (c) scanning modality used to create the media. Renderings of media representatives in the project are shown as follows: (d) Pan paniscus AMNH-M 86857 cranium (https://doi.org/10.17602/M2/M88207) and humerus (https://doi.org/10.17602/M2/M88215) derived from micro CT scans, (e) Gorilla beringei AMNH-M 202932 cranium (https://doi.org/10.17602/M2/M88162) and humerus (https://doi.org/10.17602/M2/M88167) derived from medical CT scans, (f) Pongo pygmaeus AMNH-M 145301 cranium (https://doi.org/10.17602/M2/M95438) and humerus (https://doi.org/10.17602/M2/M95445) derived from structured light scans, (g) Hylobates klossii AMNH-M 103344 cranium (https://doi.org/10.17602/M2/M87631) and humerus (https://doi.org/10.17602/M2/M87641) derived from structured light scans, (h) Pan troglodytes SBU-Apa-5 juvenile skeleton in articulation (https://doi.org/10.17602/M2/M76619) derived from medical CT scans, (i) Nasalis larvatus AMNH-M 103669 hand (https://doi.org/10.17602/M2/M84422) and foot (https://doi.org/10.17602/M2/M84483) bones derived from micro CT scans. The humeri next to the crania in panels (d-g) represent individuals from which various postcranial elements were digitized (not only the humerus).

The dataset includes detailed skeletal coverage of specimens of particular scientific interest. For example, an adult female bonobo with an inferred body mass of ~23 kg (Pan paniscus, AMNH-M 86857; Fig. 2d), which is the smallest wild-collected individual of this species on record (based on the femoral head diameter-body mass genus-specific regressions of William L. Jungers reported in ref. 27). The dataset also includes the holotype of the Grauer gorilla housed at the Royal Museum for Central Africa (RMCA 8187, listed in their catalogue under Gorilla gorilla rex-pygmaerum), and the gorilla figured in Fig. 2e (AMNH-M 202932), listed in iDigBio as a Gorilla gorilla. However, there is evidence (including museum records and anatomical details) suggesting that this latter is the large male Gorilla beringei graueri collected by Henry C. Raven in 1929 near Lake Kivu as a part of the Columbia University-AMNH expedition29, a specimen that was later pivotal in Raven’s landmark monograph on gorilla anatomy30.

To our knowledge, this represents the largest 3D morphological dataset of its kind in primates. Making it freely available will help enable more widespread research using ever larger and more taxonomically and morphologically comprehensive phenotypic datasets. In addition, being managed through MorphoSource by the different collections involved will ensure its usage can be tracked and recognized. We hope it will fuel the investigation of many open questions regarding primate evolution, including those relevant to human origins (e.g., ref. 31).

Methods

Museum curation

The specimen selection focused on adult individuals without signs of pathology affecting their overall morphology. Surface scanning was performed in the physical spaces allocated for research visitors at the collections mentioned above (AMNH, NMNH, RMCA, CMNH, SBU). Medical CT scanning occurred at SBU’s Department of Radiology, whereas micro CT scanning was performed at the AMNH’s Microscopy and Imaging Facility.

Digitization devices

Specimens in the dataset were originally digitized for different projects using several scanning devices and their proprietary software (Fig. 2c): structured light (3D Systems GeoMagic 3D Capture Scanner, Shining 3D EinScan Pro+), laser (NextEngine 3D Laser Scanner), medical CT (General Electric LightSpeed VCT 64-slice CT), and micro CT (General Electric phoenix v|tome|x, with a few meshes derived from image stacks present in MorphoSource obtained with a Nikon Metrology HMX ST 225).

Digitization protocols

Specimens scanned with the NextEngine 3D Laser Scanner were obtained using a resolution of >10,000 points per square inch; 6–12 scans were taken from overlapping views and subsequently merged using ScanStudio HD PRO software (Next Engine, Santa Monica). Scanning via the Geomagic Capture scanner was done using Geomagic Wrap (v. 2021; 3D Systems), using the software’s medium resolution setting (roughly comparable to the former NextEngine settings), taking 8–12 scans per rotation depending on the qualities of the specimen (e.g., colour, surface texture). An equivalent protocol was followed for specimens scanned using the Shining EinScan Pro+ device (using EinScan proprietary software). Medical CT scans were obtained (using GE’s specific proprietary software) with slice intervals up to 0.187 mm. Micro CT scans were obtained with voxel resolutions of 0.080 mm or smaller, also using GE’s specific proprietary software. Specific details for the medical CT and micro CT scanning protocols and 3D mesh production are extensively described in previous studies32,33,34 All 3D meshes produced were cleaned and post-processed (e.g., filling holes, fixing mesh irregularities) using automated functions in Geomagic Wrap. Further details regarding the specific settings employed to obtain each of the 6,000+ media in this project are available as metadata in MorphoSource (see Data Records below).

Data Records

All digital specimens are available in the project “Primate Phenotypes” (Project ID 00000C706)35 hosted in the online repository MorphoSource at the following URL address: https://www.morphosource.org/projects/00000C706/

Data discovery and access

MorphoSource provides search tools to allow users to identify and download data that are most relevant and useful to the user. Searching scans in MorphoSource can be filtered by “Media Type” (3D meshes and CT scans), “Object” (primate specimens), “Organization” (the collections represented), “Publication Status” (all with open download, in this case), “Taxonomy” (species present in the dataset), “Team” (the MorphoSource digital counterpart of the museum collections involved), “Project” (same media can appear in more than one MorphoSource project), “Data Manager” (for each media collection), “Data Uploader” (who uploaded the data to MorphoSource), and “Access” (the total amount of media in the project, in this case).

Search returns on biological specimens available in the project described here will also yield media produced by other projects and contributors, as other researchers have scanned and uploaded other media representing the same skeletal specimens. Therefore, it is possible to use the search and discovery tools to leverage the efforts of many different contributors who have worked on the same skeletal material, not just the contents of this dataset. In addition, each MorphoSource media dataset is associated with a wide range of comprehensive technical metadata, including (among others) the specific resolution and other data qualities (e.g., mesh point count, bounding box dimension, vertex colour, CT image pixel dimensions, and so on). The full list of specimens and associated metadata can be downloaded as a file under the “Export” option (also included here as Supplementary Table 1).

To download and use media, users must create a free MorphoSource account so data contributors, museum curators, collection managers, and other stakeholders can track the use and scholarly impact of the data. To do so, the users only need to select the desired media and add them to their “cart” (see Usage Notes below for more details).

Data format

The downloaded (zipped) MorphoSource media folder will contain subfolders with the individual scans (identified by their specific MorphoSource Media number), as well as CSV and XLS files with the metadata (columns) associated with each downloaded media (rows), and a PDF with the usage agreement. All 3D meshes in the dataset are available as PLY files (Polygon File Format or Stanford Triangle Format, using binary coding), arguably the most standard 3D mesh format. Medical and micro CT scans are saved as stacks of DICOM (Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine) or TIFF (Tag Image File Format) images. Once downloaded (and decompressed), users are free to collect their own data from the scans (see Usage Notes below for further guidelines).

Technical Validation

We examined the differences among a set of measurements taken from 46 meshes (representing 23 same bone pairs) present in this dataset that were opportunistically digitized using two different types of scanners (laser, structured light, medical, or micro CT) or two different scanners of the same type (structured light). Furthermore, in one case, we were able to inspect the differences between two meshes derived from the same medical CT scan by two different users. An inter-landmark distance, an angle, the surface area, and the volume were collected from each digitally rendered specimen in Geomagic Wrap (2021; 3D Systems). Eight replicates of each linear distance and angle were measured between six and 24 hours apart on consecutive days by a single observer (K.D.P.). Linear distances were measured by placing two landmarks on the surface of each mesh and measuring the distance between them. Angles were measured by adding a third point, defining two lines between the three landmarks, and measuring the angle between the two lines. Surface area and volume values were generated using automated functions in Geomagic Wrap.

Supplementary Table 2 presents the definition of each measurement for each bone used in our technical validation exercise and the summary statistics for all comparisons: The mean, range, standard deviation (SD), and coefficient of variation (CV [mean/SD]) were calculated for each of the linear distances and angles. Surface area and volume were not measured multiple times because values were automatically generated by Geomagic. The difference between the mean values of the eight repetitions of the linear and angular measurements, as well as the single values for surface area and volume collected on each pair of specimens, was evaluated by calculating the percentage difference between the values for each [((Value 1-Value 2)/average of Values 1-2)*100].

On average, all differences are below 5% (linear distance = 0.89%, angle = 2.65%, surface = 2.03%, volume = 4.15%). Larger differences for 3D volumes compared to linear measures are expected both because a uniform linear difference between 3D shapes will always produce a volume difference that scales to the third power and because a volume measure may capture variance along axes not characterized by our specific linear measures. In addition, some meshes are made from CT scans, and thus, volumes are more likely to be affected based on thresholding methods36 Interestingly, comparison #9 (AMNH-M 81652 capitate of a Gorilla gorilla), representing two meshes obtained from the same medical CT but processed by two different users, exhibits a volume error of only 0.02%. These results indicate that although dataset users should exercise caution and evaluate scans on a case-by-case basis, using these data in broader comparisons is relatively safe (particularly in studies that address questions above the species level). The same rationale applies when combining these scans with those from other sources, especially when the scans were digitized using the same device. In addition, since scanning details in each case are available as metadata, future comparative studies could include the overserved device effect (among others). In general, these results concur with previous studies showing that 3D meshes obtained using different scanning techniques can produce reliable and repeatable measurements37,38.

Usage Notes

3D surfaces

All 3D meshes are available in PLY format, which can be visualized, edited, and used to collect morphometric data with virtually any 3D imaging software such as Geomagic, Avizo, Amira, or the open-source MeshLab (https://www.meshlab.net/). Most modern computers (including smartphones and tablets) will open the 3D surface files (e.g., using MeshLab).

CT scans

These data appear as a stack of 2D images, each representing a cross-section through the specimen. Both DICOM and TIFF formats can be read by Avizo, Amira, or freeware Fiji (https://fiji.sc/). The latter is very useful for viewing the image cross sections, reading any embedded metadata, and exporting to different formats. 3D visualization of these data is most easily done in the same software, as well as VG Studio Max, or freeware such as 3D Slicer (https://www.slicer.org/) or the non-commercial version of Dragonfly (https://dragonfly.comet.tech/). While DICOM data have embedded relevant metadata such as voxel size, TIFF stacks don’t, and the user must refer to the metadata available in the MorphoSource project. To open CT stacks, we recommend using specialized computers with RAM exceeding the complete sample file size (twice as much, ideally). Otherwise, most software will not open all the images of the scan stack. For 3D visualization of the CT stacks, the computer must be equipped with at least two times more RAM than the file size for properly processing the data, as well as with a 64-bit operating system (OS). In general, a computer with at least 12 GB of RAM will suffice. Besides these basic conditions, the most important components are a high-clock-speed processor (>3 GHz) with two or more cores and a dedicated graphics card (≥2 GB of VRAM).

Permissions and ethical considerations

Through agreement with the curators and/or collection managers of each museum collection, all data in this project can be freely downloaded and used under a CC BY-NC Creative Commons license, which means the data can be downloaded and reused for any non-commercial purposes with the proper attribution. This is a requirement from the museum collections with scans in this dataset. Each of them has a digital counterpart in MorphoSource (as a “Team”), which maintains records documenting each collection “organization” (whether a museum division or a university department). In this way, MorphoSource empowers collection staff to track and manage media in the repository representing their specimen collection.

Regarding this dataset, the long-term licensing and actual management of the data have been transferred to representatives of the museums where the physical specimens reside (via their MorphoSource “Team”). This is sometimes a requirement set by museums that researchers must agree to before scanning. However, we believe it is also in the best interest of a researcher’s scientific legacy and the practice of science in general to allow museums to manage these media resources. The reasoning is that if we were to retain these media as our private data, few stakeholders would be willing or able to continue hosting this dataset in useful ways when we retire (to say nothing of unforeseen accidents). On the other hand, museum institutions have a mandate to preserve and make accessible data resources related to the physical specimens they hold (if they own and/or hold licenses to said imagery). These issues have been raised before (e.g., refs. 39,40).

As mentioned above, MorphoSource provides the necessary collection of provenance, taxonomic, anatomical, and digitization metadata for all the media in this project so they can be readily used. Regarding the origins of the physical specimens for which data were collected (e.g., time, place, or manner of collection), in many cases, these data are not readily available through MorphoSource or might be incomplete. The reasons for this are various. In some cases, they were never recorded. In others, field notes may be available, but many standard pieces of information often need to be added to museum catalogues. On the bright side, future updates to museum databases will be automatically pushed to MorphoSource through regular API calls. In the meantime, we encourage users interested in further details to contact each collection directly (details under the specimen’s “General Details > Organization”). Most of the primate specimens in this project were collected in the wild (decades, if not over a century ago), and many such specimens were sold to museums without details concerning exactly where, how, or by whom they were collected. It should be no surprise that many historical practices used to acquire such specimens might not meet today’s ethical standards for data reporting or humane and ethical collecting. Given that we cannot change the past and that these collections have provided and continue to provide invaluable knowledge for advancing science, we hope that facilitating worldwide open access to high-quality data from these specimens (including the nations where the animals originated) is the best way to work towards the goal of a “global collection”41 In addition, given that the managing of these data has been delegated to each of the museum collections involved, future changes in usage policy that could arise can be readily updated by each museum with downstream effects in all the media under their care.

Data tracking

In an age where digital representations are easily fabricated by Artificial Intelligence software, the notion of trusting the fidelity of media image representations that cannot, in theory, be compared directly to the physical specimen they represent is increasingly tenuous. Thanks to MorphoSource data-tracking tools, a collection staff can compare any given physical specimen to a purported digital representation by referencing the physical voucher specimens in their care. In addition, MorphoSource maintains MD5 hashes and checksums for its files to ensure the integrity of the data deposited there. We know of no other digital resource with a management structure that ensures the ability to validate data by direct comparison to physical specimens. Currently, museum staff actively manages over half of MorphoSource’s 200,000 datasets.

Finally, MorphoSource assigns a digital object identifier (DOI) to each individual media, representing a persistent identifier and URL link to the data. It is essential that publications using scans from this dataset list the individual DOIs of the used scans in the main text, as this is the only way in which the managers of each collection involved can track the usage of the data associated with specimens under their care.

Code availability

No custom code was used.

References

Goffeau, A. et al. Life with 6000 genes. Science 274, 546–567 (1996).

The C. elegans Sequencing Consortium. Genome sequence of the nematode C. elegans: A platform for investigating biology. Science 282, 2012–2018 (1998).

Adams, M. D. et al. The genome sequence of Drosophila melanogaster. Science 287, 2185–2195 (2000).

The Arabidopsis Genome Initiative. Analysis of the genome sequence of the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature 408, 796–815 (2000).

Mouse Genome Sequencing Consortium. Initial sequencing and comparative analysis of the mouse genome. Nature 420, 520–562 (2002).

International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature 409, 860–921 (2001).

The Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium. Initial sequence of the chimpanzee genome and comparison with the human genome. Nature 437, 69–87 (2005).

Prüfer, K. et al. The bonobo genome compared with the chimpanzee and human genomes. Nature 486, 527–531 (2012).

Scally, A. et al. Insights into hominid evolution from the gorilla genome sequence. Nature 483, 169–175 (2012).

Xue, Y. et al. Mountain gorilla genomes reveal the impact of long-term population decline and inbreeding. Science 348, 242–245 (2015).

Locke, D. P. et al. Comparative and demographic analysis of orang-utan genomes. Nature 469, 529–533 (2011).

Carbone, L. et al. Gibbon genome and the fast karyotype evolution of small apes. Nature 513, 195–201 (2014).

O’Leary, M. A. et al. The placental mammal ancestor and the post-K-Pg radiation of placentals. Science 339, 662–667 (2013).

Mahler, D. L., Ingram, T., Revell, L. J. & Losos, J. B. Exceptional convergence on the macroevolutionary landscape in island lizard radiations. Science 341, 292–295 (2013).

Pigot, A. L. et al. Macroevolutionary convergence connects morphological form to ecological function in birds. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 4, 230–239 (2020).

Orkney, A., Bjarnason, A., Tronrud, B. C. & Benson, R. B. J. Patterns of skeletal integration in birds reveal that adaptation of element shapes enables coordinated evolution between anatomical modules. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 5, 1250–1258 (2021).

Navalón, G., Bjarnason, A., Griffiths, E. & Benson, R. B. J. Environmental signal in the evolutionary diversification of bird skeletons. Nature 611, 306–311 (2022).

Delson, E., Harcourt-Smith, W. E. H., Frost, S. R. & Norris, C. A. Databases, data access, and data sharing in paleoanthropology: First steps. Evol. Anthropol. 16, 161–163 (2007).

Mulligan, C. J., Boyer, D. M., Turner, T. R., Delson, E. & Leonard, W. R. Data sharing in biological anthropology. Am. J. Biol. Anthropol. 178, 26–53 (2022).

Hipsley, C. A. & Sherratt, E. Psychology, not technology, is our biggest challenge to open digital morphology data. Sci. Data 6, 41 (2019).

Copes, L. E., Lucas, L. M., Thostenson, J. O., Hoekstra, H. E. & Boyer, D. M. A collection of non-human primate computed tomography scans housed in MorphoSource, a repository for 3D data. Sci. Data 3, 160001 (2016).

Bjarnason, A. & Benson, R. A 3D geometric morphometric dataset quantifying skeletal variation in birds. MorphoMuseuM 7 (2021).

Blackburn, D. C. et al. Increasing the impact of vertebrate scientific collections through 3D imaging: The openVertebrate (oVert) Thematic Collections Network. BioScience 74, 169–186 (2024).

Almécija, S. et al. The femur of Orrorin tugenensis exhibits morphometric affinities with both Miocene apes and later hominins. Nat. Commun. 4, 2888 (2013).

Alba, D. M. et al. Miocene small-bodied ape from Eurasia sheds light on hominoid evolution. Science 350, aab2625-2621–aab2625-2611 (2015).

Almécija, S., Orr, C. M., Tocheri, M. W., Patel, B. A. & Jungers, W. L. Exploring phylogenetic and functional signals in complex morphologies: The hamate of extant anthropoids as a test‐case study. Anat. Rec. 298, 212–229 (2015).

Almécija, S., Smaers, J. B. & Jungers, W. L. The evolution of human and ape hand proportions. Nat. Commun. 6, 7717 (2015).

Davies, T. G. et al. Open data and digital morphology. P. Roy. Soc. B 284, 20170194 (2017).

Raven, H. C. Gorilla: Greatest of all apes. Sci. Am. 146, 18–21 (1932).

Atkinson, W. B. et al. The Henry Cushier Raven Memorial Volume: The Anatomy of the Gorilla. (Columbia University Press, 1950).

Almécija, S. et al. Fossil apes and human evolution. Science 372, eabb4363 (2021).

Fernández, P. J. et al. Functional aspects of metatarsal head shape in humans, apes, and old world monkeys. J. Hum. Evol. 86, 136–146 (2015).

Patel, B. A., Yapuncich, G. S., Tran, C. & Nengo, I. O. Catarrhine hallucal metatarsals from the early Miocene site of Songhor, Kenya. J. Hum. Evol. 108, 176–198 (2017).

Patel, B. A. et al. Inter-ray variation in metatarsal strength properties in humans and African apes: Implications for inferring bipedal biomechanics in the Olduvai. Hominid 8 foot. J. Hum. Evol. 121, 147–165 (2018).

Almécija, S. et al. Primate Phenotypes. MorphoSource, https://doi.org/10.17602/M2/L656244 (2024).

Coleman, M. N. & Colbert, M. W. Technical note: CT thresholding protocols for taking measurements on three-dimensional models. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 133, 723–725 (2007).

Tocheri, M. W. et al. Ecological divergence and medial cuneiform morphology in gorillas. J. Hum. Evol. 60, 171–184 (2011).

Shearer, B. M. et al. Evaluating causes of error in landmark-based data collection using scanners. PLoS ONE 12, e0187452 (2017).

Gilissen, E. Museum collections, scanning, and data access. J. Anthropol. Sci. 87, 223–226 (2009).

Gilissen, E. Data sharing in the case of scanned museum collections: Suggestions for best practice. Newsletter-European Distributed Institute of Taxonomy 14, 11–12 (2009).

Johnson, K. R., Owens, I. F. P. & Global Collection Group, t. A global approach for natural history museum collections. Science 379, 1192–1194 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors want to acknowledge all the following students for their assistance in the different processes of data collection, processing, managing, and cloud uploading (in alphabetical order): Angelique Aiello, Aida Anderson, Maryse Biernat, Eleanor Cordiner, Eva Fuentes, Tajaun Gibbison, Louis Gorgone, Susanna Israelsson, Sharon Kuo, Kathryn Lauria, Sean Lee, Sylvain Nyandwi, Kelly Ostrofsky, Angela Peña, Alexander Prücha, Rowan Sherwood, Natalie Toews, Marie Vanhoof, and Dan Wawrzyniak. We are also grateful to the late Bill Jungers, Morgan Chase (and the rest of the AMNH Microscopy and Imaging Facility), the CMNH (especially Christine A. Bailey and Hailey Majewski), and all the museum collections staff for helping us over the years in making this project possible. Funding: Wenner-Gren Foundation, National Science Foundation (BCS 1316947, BCS 1317047, BCS 1539741, BCS 2316552, DGE 0966166, DBI 2149257, DBI 2311380), Leakey Foundation, Agencia Estatal de Investigación of the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación from Spain (PID2020-116908GB-I00/AEI/10.13039/501100011033), the Generalitat de Catalunya/CERCA Programme, as well as supporting funds from the AMNH, the NMNH, The George Washington University, and Stony Brook University. 40 3D meshes (crania) were derived from the CT data presented in Copes et al., 2016 (SciData), funding for the collection of which was provided by NSF DDIG #0925793, and a Wenner-Gren Foundation Dissertation Grant #8102 (both to Lynn Copes). Two further cranial 3D meshes were derived from CT scans in MorphoSource’s project “Griffin dissertation data”. Specific details about which grant funded each media are available as MorphoSource metadata.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.A. and S.A.C. conceived the project and raised funds to execute it. S.A., K.D.P., A.A., C.M.S., and A.S.H. collected, processed, and managed the data. S.A., K.D.P., and C.M.S. designed the figures. K.D.P. performed the technical validation. N.B.S, R.S.V., N.D., D.P.L., M.K.V., T.H., E.G., and S.A.M. curated the physical specimens in their respective natural collections and acted as MorphoSource liaisons. J.M.W. and D.M.B. provided technical support for uploading and organizing the data in MorphoSource. S.A., K.D.P., B.A.P., C.O., M.W.T., E.D., A.S.H, D.M.B., and S.A.C. wrote the paper with the input from the other co-authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Almécija, S., Pugh, K.D., Anaya, A. et al. Primate Phenotypes: A Multi-Institution Collection of 3D Morphological Data Housed in MorphoSource. Sci Data 11, 1391 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-04261-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-04261-5