Abstract

Bangladeshi indigenous chicken varieties - Common Deshi, Hilly and Naked Neck are notable for their egg production, meat quality, extraordinary survivability and disease resistance. However, the potential to harness their unique genetic merits are being eroded by various factors, including crossbreeding. In-depth genomic studies have not been carried out on these breeds so far. To this end, blood samples and associated phenotypic metadata have been collected from local, unimproved birds sampled from 8 different locations across the country, and from Bangladesh Livestock Research Institute (BLRI)-improved chickens of the same mentioned breeds. Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) of 96 selected samples, representing local and improved populations of each breed, has been carried out. Around 22 M high-quality SNPs have been identified, with 25% of these being novel variants previously undescribed in public databases. This data set will allow for genetic comparison between breeds, and between selected and unimproved birds, providing a resource for genomic selection in Bangladeshi breeding schemes to create more productive and resilient poultry stock.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

There are several native chicken varieties in Bangladesh of which Common Deshi (CD) or Non-descript Deshi, Hilly (HL) and Naked Neck (NN) chickens are noteworthy for their egg production, meat quality and survivability in harsh environmental conditions. Consumers prefer indigenous chicken meat and eggs due to their special characteristics of smell, taste and texture1,2. Some studies found that around 98% of consumers pay attention to particular qualities such as fat content, meat colour and taste, eggshell colour, size and yolk colour3. Domestic local chicken is thus preferred over intensively produced commercial hybrid chicken in Bangladesh.

However, these precious chicken populations have been undergoing genetic erosion since the introduction of improved stocks (both pure lines of different chicken breeds and commercial hybrids) from developed countries. This has occurred as a result of various factors like the incorporation of exotic chicken breeds and commercial hybrids, indiscriminate cross-breeding, sub-optimal breeding strategies and lack of conservation programmes2,4. Recognising the potential of Bangladeshi local chicken varieties, the Bangladesh Livestock Research Institute (BLRI) started a conservation and improvement programme for the three above-mentioned native chicken varieties around 20115, applying conventional breeding strategies. Both egg production and growth performance have improved significantly as compared to the foundation stock6,7,8. These native chickens maintained by the BLRI are known as ‘BLRI Improved Native Chicken’. However, apart from a few studies using RAPD markers, microsatellite markers or partial mitochondrial DNA-loop sequences to understand the maternal origin9,10,11,12, advanced genomic research on these native breeds has yet to be conducted. In-depth genome-level research on these promising native chicken species will be crucial for the identification of potential genomic regions and candidate genes responsible for productivity improvement, disease resistance and stress tolerance potential, to harvest maximum utilization. In addition, appropriate breeding strategies based on genomic surveys need to be undertaken for the conservation of native chicken germplasms.

Advances in genomics have enabled Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS), allowing scientists to uncover genomic insights, contributing to livestock breeding and development13,14,15,16,17,18,19. For instance, WGS analysis of 234 indigenous African chickens identified around 15 million SNPs, of which 14% represent unique variants, with some being associated with environmental adaptation and other important traits20.

In this article, we report whole-genome sequencing data from 96 Bangladeshi native chickens. The samples include BLRI improved native chickens and the same variety of local chickens from eight different locations across the country. The indigenous chicken samples taken from various villages in Bangladesh are referred to here as ‘Unimproved Native Chicken’. Paired-end next-generation sequencing for short reads was carried out on all samples with an average 23X coverage and reads mapped to the GRCg7b chicken reference genome (GCA_016699485.1; https://ftp.ensembl.org/pub/release-109/fasta/gallus_gallus/dna/). More than 22 million biallelic Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) were identified in this study, with 25% being novel variants.

The utility of data generated from the present study is expected to include helping evaluate genetic variation and diversity of Bangladeshi native chicken varieties, detecting important genomic regions and candidate genes underlying different economic traits of interest (for example, egg production, body weight and stress tolerance ability) and future investigation on genomic selection as a potential strategy in chicken breeding programmes. The data can also help make associations between the genome and the environment using Ecological Niche Modelling (ENM)21,22,23,24,25 and aid in the development of SNP chips/imputation panels26,27,28,29,30. This is the first-time whole genome sequencing from Bangladeshi native chicken varieties has been presented, at scale, thus providing a valuable resource for avian researchers to understand the genetics of local chickens. These WGS data will also help to enrich the efforts of the Chicken Genomic Diversity Consortium31 to reveal origins and adaptations of global chicken populations.

Methods

Sampling locations

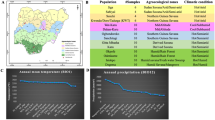

390 blood samples were collected from birds from different geographical locations in Bangladesh (Fig. 1) between February and June 2022. Of the total samples, 215 blood samples were taken from BLRI-improved chickens represented by three native varieties (Common Deshi, Hilly and Naked Neck) at the BLRI Poultry Research Farm. 175 blood samples were also taken from unimproved indigenous chickens (of the same three breeds) from several villages in eight different geographical locations across the country. While selecting the sampling sites, different environmental or climatic factors like temperature and humidity variation and availability of native chicken variety in that particular region, were taken into consideration. Details of the collected samples are shown in Fig. 1 and described in Supplementary Table 1.

Sample collection sites from across Bangladesh. Blue circles indicate unimproved native chicken sampling locations (across the different villages) while the red circle indicates the improved native chicken sampling location (BLRI Headquarters, Dhaka, Bangladesh). The numbers inside the circles indicate the number of samples that were sequenced from each location.

Ethical approval

All relevant ethical approvals were obtained from the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee (AEEC) of BLRI [AEEC/BLRI00116]. In addition, prior collection of blood samples from the village chickens was done with the full consent of the owners. The samples were transported to the United Kingdom under a material transfer agreement (MTA) between BLRI and The University of Edinburgh (MTA Roslin 3324). In addition, import authorization for blood samples was issued under the Trade in Animals and Related Products (Scotland) Regulations (2012).

Blood collection

Around 0.5 ml blood was withdrawn from the brachial wing vein (or cutaneous ulnar vein) of the selected healthy chickens using 1.0 ml insulin syringe (JMI Syringes & Medical Devices Limited, Bangladesh) following the procedure stated by Kelly and Alworth32. Chickens were handled with extreme care, maintaining standard animal handling procedures to ensure minimum stress. Immediately after collection, the blood was gently and carefully spread onto Whatman FTA classic cards (Cat. No: WHAWB120205; Merck, Germany). After completion of blood collection, the FTA cards were kept at room temperature for at least three hours to allow complete drying. Appropriate caution was taken to keep the FTA cards safe from direct sunlight. All air-dried blood samples were then stored safely in double zipper bags until further processing at the Roslin Institute (Edinburgh, UK).

Sample selection for WGS

For whole genome sequencing, a total of 96 samples were selected from the 390 samples collected. The selected samples consisted of equal numbers of male and female chickens from each of the 6 groups (3 improved and 3 unimproved indigenous chicken varieties) as shown in Table 1. In the case of selecting BLRI-improved native chickens, unrelated chickens were given priority, considering the pedigree data (parental information) of the previous two generations of the sampled chicken populations. Samples from all geographical locations were included while selecting unimproved chickens for WGS. Again, within the same sampling area, individuals were selected from different villages.

Sample preparation for WGS

All the selected blood samples on FTA cards were processed using a QIAamp® DNA Investigator-50 kit (CAT no: 56504; QIAGEN, Germany). The quality and the quantity of the isolated genomic DNA were assessed by three different instruments - NanoDrop 1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), Qubit 4 fluorometer (Invitrogen, USA) and TapeStation 4200 (Agilent Technologies, USA). After normalising to a final volume of 50 μL, the genomic DNA samples were sent to BGI Genomics, Poland for whole genome sequencing (150 bp paired-end, 20X coverage).

Library preparation and sequencing

Library preparation was conducted at BGI Genomics in Poland. Before sequencing, concentration, integrity and purity of all the genomic DNA samples were again checked. Concentration was determined by Qubit Fluorometer (Invitrogen) and sample integrity and purity were detected by Agarose Gel Electrophoresis (concentration of agarose gel: 1%, voltage: 150 V, electrophoresis time: 40 minutes). Random fragmentation of genomic DNA was done using a Covaris (E220) instrument, then the fragmented genomic DNA was selected by Magnetic beads [Cat no: 1000005278 (MGI Easy DNA Clean Beads; https://en.mgi-tech.com/Products/reagents_info/id/7] to an average size of 200–400 bp. Fragments were then end repaired and 3′ adenylated, with adaptors then ligated to the ends of these 3′ adenylated fragments. PCR was then carried out to amplify the fragments with adaptors and PCR products were purified by magnetic beads. The double stranded PCR products were then denatured and circularised by the splint oligo sequence. The single strand circular DNA (ssCir DNA) was formatted as the final library. The library was then assessed by quality control. The library was amplified with phi29 to make DNA nanoballs (DNB) which have more than 300 copies of each molecule. The DNBs were loaded into the patterned nanoarray and paired end 150 bp reads were generated by combinational Probe-Anchor Synthesis (cPAS). The sequencing was performed using the next generation high-throughput platform at BGI Genomics (DNBSEQ-T7) in paired-end mode (~20X coverage).

Data processing

Raw reads were filtered using a series of data processing steps to remove adaptor sequences, contamination and low-quality reads. This was done using SOAPnuke software33 by BGI Genomics. Upon receipt of sequence data, quality of the sequences was checked using the FastQC programme (version 0.11.7)34. For ease of reviewing the sequence quality, FASTQC reports for all 96 samples were aggregated in a single report by the MultiQC (version 1.1) package35, examples from which are shown in Fig. 2. No adaptor sequences were present and as the quality of the raw reads was very high, no further quality-based trimming was performed on the sequence reads.

Mapping of the sequence reads was performed against the GRCg7b chicken reference genome (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/browser/view/GCA_016699485.1) using Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (bwa-version 0.7.15)36,37 with default parameters. Before alignment, sequence dictionary and FASTA index files were created using Samtools (version 1.13)38 which were used by the BWA-MEM programme. The resultant Sequence Alignment Map (SAM) files then underwent some further processing steps such as sorting according to their coordinates using the SortSam programme of Picard tools (version 2.25.4)39 and marking duplicate reads using the MarkDuplicate programme of the same tool. BAM files were then validated to troubleshoot errors such as improper formatting, faulty alignments and incorrect flag values. In addition, different WGS metrics were calculated using both Samtools and Picard tools. Base Quality Score Recalibration (BQSR) was then carried out using the BaseRecalibrator tool from the Genome Analysis Toolkit - GATK (version 4.0.10.1)40,41 to correct the biases in the quality scores assigned by the sequencer. The final recalibrated BAM files were then used for further downstream analysis. The overview of the mapping and variant calling steps is presented in Fig. 3.

GATK best practice guidelines for germline short variant discovery were followed for variant calling and SNP detection using the HaplotypeCaller tool with the ‘-ERC GVCF’ settings to generate GVCF files which then underwent joint genotyping using the GenomicsDBImport and then GenotypeGVCFs functions. The Variant Quality Score Recalibration (VQSR)42 function was then applied to perform variant filtration using a set of around one million validated SNPs26 as a training and true set, with over 21 M chicken SNPs from the Ensembl database (release-110)43 used as known variants.

The following annotations or context statistics were considered during the VQSR step: read depth (DP), variant quality by depth (QD), root mean square mapping quality (MQ), mapping quality rank sum test statistics (MQRankSum), read position rank sum test statistics (ReadPosRankSum), and strand bias statistics (FS and SOR). A tranche sensitivity threshold of 99% was applied for filtering variants. As the final quality control of the called variants, any SNPs with a missing genotype rate more than 10% across the samples were filtered out using VCFtools44 (version 0.1.13).

All codes used for the mapping and variant calling steps are included in the Supplementary materials and also available on GitHub.

Data Records

All full-length raw sequencing data in FASTQ format can be accessed from the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) of the NCBI database under BioProject accession number PRJNA102732545. The filtered VCF file containing more than 22 million high-quality autosomal biallelic SNPs can also be accessed from the European Necleotide Archive (ENA) and the European Variation Archive (EVA) repositories under the Project accession number PRJEB7835746,47 and Analysis accession number ERZ24818048.

Technical Validation

Quality control of sequencing data

The total number of bases generated from the sequencing each sample was from 24 Gb to 28 Gb, with GC content averaging 42%. Around 95.33% of the bases had a minimum Phred scaled quality score of 30 which indicates a base calling accuracy of 99.9%. The average estimated genome coverage across all sample was ~23X (after marking duplicate reads) with the range varying from 20X to 25X. FastQC reports (shown in Fig. 2) indicate that sequencing quality of all samples was of high-quality. The average mapping rate of the sequence reads against the reference genome was 99.60%, which further confirmed the high quality of the sequencing data.

Quality control of SNP data

During the variant calling step using GATK best practice guidelines, more than 30 M total variants were identified including more than 26 M SNPs and 4.5 M insertions/deletions (INDELs). VQSR filtering was then applied to ensure identification of high-quality variants and to minimize the number of false positives. More than 1 M validated SNPs26 and about 22 M SNPs from Ensembl43 were used as known variants (training data set) during the VQSR step. The VQSR filtering retained 100% of the SNPs (26.07 M). Next, only the biallelic SNPs (22.75 M) were taken into consideration for downstream analysis which included a further filtering step. SNPs with a missing genotype rate of more than 10% were discarded, which retained around 22 M high-quality SNPs. In this step, minimum genotype quality (GQ) score was considered 20 (–minGQ 20.0), depth of sequence coverage was 3 (–minDP 3), Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE) value was 0.00001 (–hwe 0.00001) along with the maximum missing rate of genotypes of 10% (–max-missing 0.9) using VCFtools. Annotation of the identified SNPs was done using Ensembl’s Variant Effect Predictor-VEP48 (release-110) which revealed that around 75% of the total high-quality variants are already reported in the public databases, but the rest were novel variants. We found that the majority of the identified variants (around 68%) were intronic while around 2% were exonic variants (shown in Table 2a). Again, we found a greater number of variants in unimproved chicken populations compared to improved chickens of the same varieties (Table 2b). Details of SNPs in different annotation categories in both improved and unimproved native chicken populations are given in Supplementary Table 2.

To determine the quality of SNP calling from the high-throughput sequencing data, the transition/transversion ratio (Ts/Tv) can be employed. We obtained a transition/transversion ratio (Ts/Tv) of 2.453 in the overall populations which is typically found to be ~2 for whole genome sequence data49. Some previous studies reported a Ts/Tv ratio between 2.17 to 2.69 for different indigenous chicken breeds20,50,51,52,53. Unless it is too high (>4), a higher Ts/Tv ratio generally indicates better SNP calling54.

The proportion of singleton SNPs in the overall population for this study was 13.64% while the unimproved chicken populations have higher percentages compared to the improved populations (Table 2b). These reflect the genetic diversity between the studied chicken populations. In addition, smaller sample size may be also responsible for a large proportion of singleton SNPs55.

We observed an average of 1 SNP in every 57 base pairs in 10 kb non-overlapping windows across the studied genome. Indigenous chicken species exhibit higher SNP density mainly due to their greater genetic diversity, exposure to varied environmental conditions and more natural settings or less controlled breeding compared to the commercial breeds53,56,57. The SNP density across various chromosomes including the sex chromosomes (Z and W) from our study is detailed in Supplementary Table 3 and illustrated in Fig. 4.

Code availability

WGS data analyses from 96 Bangladeshi indigenous chickens were performed using standard bioinformatic tools in the Scientific Linux 7-based High Performance Computing (HPC) system (Eddie) of the University of Edinburgh. The codes used along with versions and parameters of the primary software/tools are available on GitHub (https://github.com/MAGRabbani/WGS_of_BDchicken_data_analysis_codes) and also included in the supplementary materials.

References

Das, S. C. et al. Poultry production profile and expected future projection in Bangladesh. Worlds Poult Sci J 64, 99–118 (2019).

Bhuiyan, A. K. F. H., Bhuiyan, M. S. A. & Deb, G. K. Indigenous chicken genetic resources in Bangladesh: current status and future outlook. Animal Genetic Resources Information 36, 73–84 (2005).

Bett, H. K., Peters, K. J., Nwankwo, U. M. & Bokelmann, W. Estimating consumer preferences and willingness to pay for the underutilised indigenous chicken products. Food Policy 41, 218–225 (2013).

Fakhrul Islam, S. M. & Jabbar, M. A. Scavenging Poultry for Poverty Alleviation: A Review of Experiences with a Focus on Bangladesh. (2003).

Faruque, S., Islam, M. N. & Bhuiyan, A. K. F. H. Ex situ improvement of indigenous chicken in Bangladesh. Tropical Agricultural Research 26, 13 (2015).

Faruque, S., Islam, M., Afroz, M. A. & Rahman, M. M. Evaluation of the performance of native chicken and estimation of heritability for body weight. Journal of Bangladesh Academy of Sciences 37, 93–101 (2013).

Faruque, S., Bhuiyan, A., Ali, M. Y. & Joy, Z. F. Breeding for the improvement of indigenous chickens of Bangladesh: performance of foundation stock. Asian Journal of Medical and Biological Research 3, 80–87 (2017).

Sultana, S., Faruque, S., Bhuiyan, A. & Bhuiyan, A. K. F. H. Progress in the Performance of Indigenous Chickens Selected for Economic Traits in Bangladesh. Journal of Agriculture, Food and Environment 2, (2021).

Mollah, M. B. R., Islam, F. B., Islam, M. S., Ali, M. A. & Alam, M. S. Analysis of genetic diversity in bangladeshi chicken using RAPD markers. Biotechnology 8, 462–467 (2009).

Rashid, M. A. et al. Genetic diversity and population structure of indigenous chicken of Bangladesh using microsatellite markers. Asian-Australas J Anim Sci 33, 1732–1740 (2020).

Bhuiyan, M. S. A., Chen, S., Faruque, S., Bhuiyan, A. K. F. H. & Beja-Pereira, A. Genetic diversity and maternal origin of Bangladeshi chicken. Mol Biol Rep 40, 4123–4128 (2013).

Islam, M. A., Osman, S. A. M. & Nishibori, M. Genetic diversity of Bangladeshi native chickens based on complete sequence of mitochondrial DNA D-loop region. Br Poult Sci 60, 628–637 (2019).

Okpeku, M., Ogah, D. M. & Adeleke, M. A. A review of challenges to genetic improvement of indigenous livestock for improved food production in Nigeria. African Journal of Food, Agriculture, Nutrition and Development 19, 13959–13978 (2019).

Perini, F. et al. Emerging Genetic Tools to Investigate Molecular Pathways Related to Heat Stress in Chickens: A Review. Animals (Basel) 11, 1–19 (2021).

McCarthy, M. I. et al. Genome-wide association studies for complex traits: consensus, uncertainty and challenges. Nature Reviews Genetics 2008 9:5 9, 356–369 (2008).

Cho, Y. S. et al. A large-scale genome-wide association study of Asian populations uncovers genetic factors influencing eight quantitative traits. Nature Genetics 2009 41:5 41, 527–534 (2009).

Dalloul, R. A. et al. Multi-Platform Next-Generation Sequencing of the Domestic Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo): Genome Assembly and Analysis. PLoS Biol 8, e1000475 (2010).

Uffelmann, E. et al. Genome-wide association studies. Nature Reviews Methods Primers 2021 1:1 1, 1–21 (2021).

Gheyas, A. A. et al. Integrated Environmental and Genomic Analysis Reveals the Drivers of Local Adaptation in African Indigenous Chickens. Mol Biol Evol 38, 4268–4285 (2021).

Gheyas, almas et al. Whole genome sequences of 234 indigenous african chickens from Ethiopia. Sci Data 9, (2022).

Vallejo-Trujillo, A. et al. Ecological niche modelling for delineating livestock ecotypes and exploring environmental genomic adaptation: The example of Ethiopian village chicken. Front Ecol Evol 10, 755 (2022).

Lozano-Jaramillo, M., Bastiaansen, J. W. M., Dessie, T. & Komen, H. Use of geographic information system tools to predict animal breed suitability for different agro-ecological zones. Animal 13, 1536–1543 (2019).

Jueterbock, A., Smolina, I., Coyer, J. A. & Hoarau, G. The fate of the Arctic seaweed Fucus distichus under climate change: an ecological niche modeling approach. Ecol Evol 6, 1712–1724 (2016).

Muscarella, R. et al. ENMeval: An R package for conducting spatially independent evaluations and estimating optimal model complexity for Maxent ecological niche models. Methods Ecol Evol 5, 1198–1205 (2014).

Phillips, S. B., Aneja, V. P., Kang, D. & Arya, S. P. Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions. Ecol Modell 190, 231–259 (2006).

Kranis, A. et al. Development of a high density 600K SNP genotyping array for chicken. BMC Genomics 14, 1–13 (2013).

Herry, F. et al. Design of low density SNP chips for genotype imputation in layer chicken. BMC Genet 19, 108 (2018).

Marchini, J., Howie, B., Myers, S., McVean, G. & Donnelly, P. A new multipoint method for genome-wide association studies by imputation of genotypes. Nature Genetics 2007 39:7 39, 906–913 (2007).

Browning, B. L. & Browning, S. R. Genotype Imputation with Millions of Reference Samples. The American Journal of Human Genetics 98, 116–126 (2016).

Van Leeuwen, E. M. et al. Population-specific genotype imputations using minimac or IMPUTE2. Nature Protocols 2015 10:9 10, 1285–1296 (2015).

Smith, J. et al. Fourth Report on Chicken Genes and Chromosomes 2022. Cytogenet Genome Res 162, 405–527 (2022).

Kelly, L. M. & Alworth, L. C. Techniques for collecting blood from the domestic chicken. Lab Animal 2013 42:10 42, 359–361 (2013).

Chen, Y. et al. SOAPnuke: a MapReduce acceleration-supported software for integrated quality control and preprocessing of high-throughput sequencing data. 7, 1–6 (2018).

Simon, A. FastQC A Quality Control tool for High Throughput Sequence Data. Babraham Bioinformatics https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/.

Ewels, P., Ns Magnusson, M., Lundin, S. & Aller, M. K. Data and text mining MultiQC: summarize analysis results for multiple tools and samples in a single report. Bioinformatics 32, 3047–3048 (2016).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009).

Li, H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. Preprint https://doi.org/10.6084/M9.FIGSHARE.963153.V1 (2013).

Li, H. et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009).

Broad Institute. Picard Tools - By Broad Institute. https://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/.

Van der Auwera, G. A. & O’Connor, B. D. Genomics in the Cloud: Using Docker, GATK, and WDL in Terra. (O’Reilly Media, Sebastopol, CA, 2020).

Broad Institute. Best Practices for Variant Calling with the GATK. Broad Institute https://www.broadinstitute.org/partnerships/education/broade/best-practices-variant-calling-gatk-1.

Caetano-Anolles, D. Variant Quality Score Recalibration (VQSR) – GATK. https://gatk.broadinstitute.org/hc/en-us/articles/360035531612-Variant-Quality-Score-Recalibration-VQSR (2023).

Harrison, P. W. et al. Ensembl. Nucleic Acids Res 52, 891–899 (2024).

Danecek, P. et al. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics 27, 2156–2158 (2011).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP467265 (2024).

ENA European Nucleotide Archive https://identifiers.org/ena.embl:PRJEB78357 (2024).

EVA European Variant Archive https://www.ebi.ac.uk/eva/?eva-study=PRJEB78357 (2024).

McLaren, W. et al. The Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor. Genome Biol 17, 1–14 (2016).

Wang, G. T., Peng, B. & Leal, S. M. Variant Association Tools for Quality Control and Analysis of Large-Scale Sequence and Genotyping Array Data. The American Journal of Human Genetics 94, 770–783 (2014).

Oh, D. et al. Whole Genome Re-Sequencing of Three Domesticated Chicken Breeds. Zoolog Sci 33, 73–77 (2016).

Boschiero, C. et al. Genome-wide characterization of genetic variants and putative regions under selection in meat and egg-type chicken lines. BMC Genomics 19, 1–18 (2018).

Derks, M. F. L. et al. A survey of functional genomic variation in domesticated chickens. Genet Sel Evol 50, 17 (2018).

Xu, D. et al. Whole-genome sequencing revealed genetic diversity, structure and patterns of selection in Guizhou indigenous chickens. BMC Genomics 24, 1–23 (2023).

Wang, J., Raskin, L., Samuels, D. C., Shyr, Y. & Guo, Y. Genome measures used for quality control are dependent on gene function and ancestry. Bioinformatics 31, 318–323 (2015).

Vallejo-Trujillo, A. Genetic diversity and adaptation to environmental challenges of Ethiopian indigenous chicken. (University of Nottingham, 2021).

Qanbari, S. et al. Genetics of adaptation in modern chicken. PLoS Genet 15, e1007989 (2019).

Wu, S. et al. Artificial selection footprints in indigenous and commercial chicken genomes. BMC Genomics 25, 1–20 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the BGI Genomics sequencing facility in Poland for carrying out the whole genome sequencing of the chicken samples. MAGR was funded through the Prime Minister’s Fellowship Programme under the Prime Minister’s Office of the Government of Bangladesh [Grant no 03.03.2690.094.18.04.22- 94] and the project carried out as part of the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) award number BBS/E/RL/230001 A. The authors also thankful to the authority concerned of Bangladesh Livestock Research Institute (BLRI) and The Roslin Institute, and owners of the sampled chickens.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.S. and M.A.G.R. conceived the research project; M.A.G.R. obtained funding; M.A.G.R. and S.F. led sample collection; M.A.G.R. and K.M. prepared samples for sequencing; M.A.G.R. carried out all bioinformatic analyses, A.V.T. and Z.W. supervised the bioinformatics analysis; K.W. and J.S. supervised the project; M.A.G.R. drafted the original manuscript. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rabbani, M.A.G., Vallejo-Trujillo, A., Wu, Z. et al. Whole genome sequencing of three native chicken varieties (Common Deshi, Hilly and Naked Neck) of Bangladesh. Sci Data 11, 1432 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-04291-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-04291-z

This article is cited by

-

Whole-genome variant of 220 Tibetan sheep from the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau

Scientific Data (2025)