Abstract

This paper presents an open-source dataset intended to enhance the analysis and optimization of photovoltaic (PV) power generation in urban environments, serving as a valuable resource for various applications in solar energy research and development. The dataset comprises measured PV power generation data and corresponding on-site weather data gathered from 60 grid-connected rooftop PV stations in Hong Kong over a three-year period (2021-2023). The PV power generation data was collected at 5-minute intervals at the inverter-level. The meteorological data was collected at 1-minute intervals from an on-site weather station. The metadata was represented using the Brick schema, which simplifies data comprehension and the development of smart analytics applications. This paper provides a detailed description on the site specifications, data collection method, data records, and data validation. This dataset can be used in various applications - PV generation benchmarking, PV degradation analysis, PV fault detection, solar radiation and PV power generation forecasting, and the simulation and design of PV systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

One effective approach to reduce fossil fuel consumption and to address the climate change crisis is the promotion of renewable energy resources (RERs)1. Among these resources, solar photovoltaics (PV) have experienced rapid growth, reaching a global installed capacity of 710 GWp by the end of 20202. Particularly in the residential sector, rooftop PV systems have seen significant adoption as decentralized electricity generators3. Projections from the International Energy Agency (IEA) indicate that rooftop PV capacity is expected to reach 143 GWp by 2024, a substantial increase from 58 GWp in 20184. Furthermore, annual capacity additions are anticipated to triple, surpassing 20 GWp by 20244.

The rising prevalence of rooftop photovoltaic (PV) systems highlights the critical need for their efficient and reliable operation4. The output of photovoltaic (PV) generation is greatly influenced by various meteorological factors such as solar irradiance, atmospheric temperature, module temperature, wind, pressure, and humidity5. PV systems interact with their surroundings through heat, mass, and momentum transfer, which can significantly impact power generation efficiency, system structural safety, and ambient microclimate6. Moreover, internal components (modules, connection lines, converters, inverters, etc.) are sensitive to fault occurrences7 and undergo chemical and physical degradation8 over their lifecycle. Reduced reliability in PV systems can lead to decreased energy production, increased reliance on fossil fuels, and diminished investment returns, ultimately undermining both environmental sustainability and economic viability2. In order to investigate the characteristics and challenges associated with rooftop PV systems, as well as to achieve efficient, reliable, and secure operation, it is necessary to obtain a comprehensive dataset comprising longitudinal PV generation data along with corresponding meteorological monitoring data.

Existing open-source datasets related to PV generation can be categorized into two primary types: simulation9 and on-site measurement10,11,12,13. A simulation dataset, as presented by Yuan et al., includes one year of PV generation data from the global solar energy estimator (GSEE) model, captured at 1-hour intervals from a residential rooftop PV station in Denmark9. For on-site measurement data, Agee et al. provided six years of solar energy generation data at 1-hour intervals, and two years of energy use data at 1-hour intervals for a zero-energy commercial building in Virginia, USA10. Nie et al. provided three years of PV power generation data and sky images at 1-hour and 1-minute intervals respectively, for a single residential rooftop PV station at Stanford University11. Yao et al. provided 300 days of PV generation and local measured meteorological data in 15-minute intervals from 10 utility-scale PV systems located in Hebei Province, China12. Pecan Street Dataport offers a complete source of house-level PV power generation data, including detailed measurements from different residential PV systems, allowing researchers to analyze performance metrics, usage patterns, and the impact of local environmental conditions on energy generation13.

Based on the literature review, there is a lack of open-source long-term datasets on rooftop PV generation, accompanied by locally measured meteorological data. Furthermore, the current datasets available solely provide station-level generation information, lacking inverter-level data such as voltages, frequencies, and currents on both the DC and AC sides. The differences among existing and proposed PV generation datasets are illustrated in Table 1. The existing gaps in the literature pose significant challenges for researchers and practitioners. For instance, the lack of long-term datasets complicates degradation analysis14, preventing accurate assessments of PV system performance over time under varying environmental conditions. Additionally, the lack of inverter-level data adversely affects the accuracy of performance evaluations, complicates maintenance and fault detection15, and restricts modeling and simulation16 capabilities. To address these gaps, we present a three-year dataset of rooftop PV generation and corresponding meteorological data from a subtropical university campus, which offers detailed inverter-level operational data, facilitating more precise analyses and improving the robustness of results.

The uniqueness of this dataset includes:

-

A high-resolution operational dataset was collected from 60 rooftop PV stations, encompassing a total of 6,085 PV modules (individual components consisting of interconnected solar cells designed to convert sunlight into electrical energy) over a three-year period.

-

This dataset includes inverter-level operational data (the most granular PV data, including generation and electrical data like voltages, frequencies, and currents), and on-site meteorological data (irradiation, temperature, humidity, visibility, pressure, wind, and rain).

-

A Brick model17 was developed as an open-source standardized semantic framework to represent the location, equipment, and temporal metadata for PV systems. It facilitates the development of smart analytics and control applications.

The potential use cases for the dataset can be as follows:

-

Comparing the generation efficiency of PV modules with different capacities, module models, optimizer types, and connection time18,19,20.

-

This dataset includes inverter-level operational data (the most granular PV data, including generation and electrical data like voltages, frequencies, and currents), and on-site meteorological data (irradiation, temperature, humidity, visibility, pressure, wind, and rain)21,22,23.

-

Calibrating PV generation and forecasting models developed from either data-driven or physics-based approaches16,24,25,26.

-

Developing automatic fault detection algorithms for PV modules27,28,29.

-

Longitudinal performance degradation analysis for PV system14,30,31.

Methods

The site

The data was collected from 60 grid-connected rooftop PV stations and 1 weather station. These stations are located within the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology campus. The university is located in the rural coastal area of Sai Kung District, Hong Kong (22.3363°N 114.2634°E) and covers an area of 60 hectares. The rooftop solar power project is managed by the University Sustainability/Net-Zero Office and was initiated in December 2020. Currently, it stands as the largest behind-the-meter rooftop solar power project in Hong Kong. As of December 2023, the distributed rooftop PV stations had been installed on over 95% of buildings throughout the campus. The combined power capacity amounts to 2,230.8 kWp, generated from 6,085 PV modules. This setup yields an annual electricity output of 3 million kilowatt-hours (kWh), which is equivalent to the annual electricity usage of more than 900 three-member households in Hong Kong32. For a visual representation, refer to Fig. 1, displaying a satellite image of the campus33 and the location of the PV sites as well as the meteorological station.

Satellite imagery of the campus33 indicating locations of PV stations with and without panel optimizers, the weather station, and the fixed position and model of optimizer.

PV generation data

The device architecture of the 60 rooftop PV stations is fundamentally similar, with the primary distinction being the presence or absence of panel-level optimizers; consequently, we classify them into two categories: PV stations with panel-level optimizers and those without. An overview of the electricity and communication infrastructure for each category is presented in Fig. 2.

For stations without panel-level optimizers (comprising 23 stations, accounting for 38.3% of the total), the data are individually measured and transmitted by the inverter. It is noteworthy that these 23 stations each contain only one inverter. Consequently, the power generation data measured by the inverter corresponds to inverter-level values. The inverter serves a dual purpose, functioning both as a power converter and as a means of transmitting power generation data. It converts the DC power generated by the modules into AC power, which is then supplied to the local customer AC service and subsequently fed into the grid. Simultaneously, the inverter collects power generation data at the inverter level and transmits it to a nearby wireless gateway. The gateway, with the assistance of a home router, establishes a connection to the monitoring portal.

For stations equipped with panel-level optimizers (comprising 37 stations, accounting for 61.7% of the total), the PV generation data is measured and transmitted by both the inverter and the panel-level optimizer. Each pair of PV modules is connected to a single optimizer that functions as a DC-DC Maximum Power Point Tracking (MPPT) converter34. This technology enhances energy efficiency by ensuring that each module operates at its optimal power output, thereby maximizing energy harvest and mitigating module mismatch loss—defined as the reduction in overall power output due to performance variations among individual modules35. These discrepancies may arise from factors such as manufacturing tolerances, partial shading, and aging effects35. In addition to improving energy efficiency, the optimizer also serves as a monitoring device, providing real-time module-level generation data. However, during the operational period from 2021 to 2023, we did not collect module-level generation data due to the large volume of records. Consequently, the published generation data is characterized by inverter-level granularity.

The measurement, transmission, and data granularity level of PV generation data differed depending on whether the stations were equipped with panel-level optimizers or not, as summarized in Table 2. For instance, the Tower A station, which is equipped with a single inverter and lacks panel-level optimizers, provides only inverter-level generation and power data. In contrast, the Library station, which is equipped with three inverters, offers a comprehensive dataset that includes inverter-level power generation and electrical data for each inverter, along with overall site-level generation and power metrics. This distinction highlights the variability in data availability and granularity across different station configurations, which is further elaborated in Table 2.

Meteorological data

Meteorological data is collected from the weather station located on the eastern side of the campus, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The station is located on a cliff, offering a vantage point overlooking the bay in a rural area characterized by minimal residential or commercial development. The station comprises a 10-meter-high automatic weather tower and an outdoor plinth area that houses 6 monitoring sensors, as described in Table 3, measuring meteorological data at 1-minute intervals. The collected data is transmitted to a central database using wired connections.

Data transmission and storage

The collected PV generation data was transmitted to a wireless gateway via a secure Wi-Fi connection. The wireless gateways employed include the SE-WFGW-B-S1-NA36 and the COMGATEWAY-DEN1834-V12web37. The gateway connects to the monitoring platform via Ethernet. The monitoring platform offers a centralized interface for real-time monitoring of solar systems, enabling performance tracking, remote troubleshooting, and access to both real-time and historical generation data. Two monitoring platforms were employed due to the involvement of two contractors in the installation and operation of the PV stations: the SolarEdge monitoring platform38 for SolarEdge systems and the Sunny Portal39 for SMA systems. Vendor information for each PV station is documented in the Brick Schema model, which provides essential details for users to comprehend the system’s configuration and components.

Meteorological data is initially sensed and transmitted using RS232 communication protocols before being stored in the CR10X-2M data logger40, which can accommodate up to 1,000,000 data points. This logger comprises a CR10XM-2M Measurement and Control Module and a CR10X Wiring Panel. It offers essential measurement functions and stores data in non-volatile Flash memory or RAM, supported by a lithium battery. After data collection, all streams of PV generation and meteorological data are transferred to the server and consolidated into a centralized database. The data collection process is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Data curation

We pre-processed the data by replacing missing values with “NA” and resampling the data to ensure temporal consistency. Resampling was performed using the Pandas library in Python, specifically utilizing the resample function to mitigate the effect of delays in data transmission41. This process synchronized all data points to uniform timestamps, such as 00, 05, or 10 minutes past the hour, without compromising the data’s resolution. This synchronization enhances the clarity of the dataset and facilitates the integration of various data types. It is important to note that missing values were not filled, and outlier detection was not performed. This decision was made due to the lack of ground truth for supervising missing value imputation or anomaly detection. As a result, we opted to provide the data post-resampling, which includes no data filling, enabling researchers to exercise flexibility in applying their own data cleaning strategies. This consideration is important due to the potential variation in the most suitable approach across distinct research or application domains.

Data Records

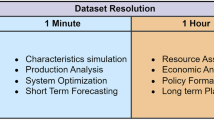

The dataset can be accessed at this Dryad repository42. As shown in Fig. 4, the open-sourced dataset is divided into two categories: time-series data and metadata. Longitudinal PV generation and meteorological data are provided in Comma-Separated Values (.csv) format, while metadata of the data measurements is represented by the Brick model in Turtle (.ttl) format. The original data has a total size of 984 MB (about 282 MB when compressed in a zip file).

Time-series data

The time-series data is classified into three major categories, based on the data source: PV stations without panel-level optimizer, PV stations with panel-level optimizer, and the weather station. The entire dataset is compiled into three folders, each containing 23, 81, and 21 data files in .csv format, respectively. Table 4 presents a summary of the available data types, units, resolutions, and overall missing rates based on Eq. (1).

The missing rate is defined as the number of missing records divided by the number of expected records. The number of expected records is calculated as the operational period divided by the temporal resolution.

In Table 4, L1, L2, and L3 represent the three phases of alternating current (AC), which are vital for balancing loads and improving efficiency in electrical systems. Each phase operates at the same frequency but is staggered, contributing to a stable power supply. In PV power generation, solar modules produce direct current (DC), which is converted to alternating current (AC) for integration into the grid43. While DC provides a stable voltage, AC facilitates efficient long-distance transmission. Active power (in watts, W) indicates useful work, while reactive power (in volt-amperes reactive, VAR) represents power oscillating between the source and load, which is crucial for maintaining voltage stability across AC phases44.

Metadata

To enhance data comprehension and enable efficient querying, we have developed a Brick model that represents the location, equipment, and temporal metadata for PV systems17. The Brick schema is an open-source standardized semantic model that describes the physical, logical and virtual assets in buildings and the relationships between them17. Its primary objective is to simplify the development of smart analytics and control applications17.

The detailed Brick model is stored in Turtle (.ttl) format, which facilitates structured metadata representation. Turtle is a syntax for expressing data in the Resource Description Framework (RDF), facilitating the representation of information about resources on the web.1 To query this metadata, we employ SPARQL (SPARQL Protocol and RDF Query Language), enabling users to perform complex queries on the RDF data and efficiently retrieve specific information. Additionally, we provide a sample Python code in the Code Availability section to retrieve system metadata using SPARQL queries. An exploration of the metadata of PV generation system in the Brick model can be conducted using the Brick TTL viewer45.

Figure 5 illustrates the entity classes, properties, instances, and their interrelationships within a PV station, emphasizing the hierarchical structure of the PV system and its associated metadata. This diagram facilitates a deeper understanding of the components of the Brick model. The azimuth is an attribute of the Brick model defined as the horizontal angle measured counterclockwise from true north (0°), with true south at 180°, true east at −90°, and true west at 90°. The tilt angle is another attribute that indicates the steepness of the panel as the angle between its surface and the horizontal plane. For PV stations with modules oriented in two equal directions, slash notation indicates that 50% of the modules face one direction while the other 50% face the opposite. In cases where PV stations are on curved roofs, the azimuth angle is classified as “Mixed” to reflect the arrangement of modules along the building’s outline.

Technical Validation

Data accuracy

Table 3 summarizes the measurement uncertainties of 6 types of meteorological sensing equipment. PV measuring devices have an accuracy of ± 2.5%, which means that every direct measurement, such as voltage, frequency, or current, may deviate up to 2.5% from the actual value. Values that are not directly measured but are calculated from various direct measurements, such as energy and generation power, have an accuracy of ± 5%. These accuracies comply with the requirements for PV monitoring applications set forth by both EU and US regulations46,47. The PV stations and sensors undergo regular maintenance as per the specifications outlined by the Hong Kong Electrical and Mechanical Services Department (EMSD) to ensure their proper functioning.

Furthermore, we conducted a data accuracy assessment by comparing the readings from different sensors using fundamental principles. In the case of solar PV plants equipped with panel optimizers, data is collected at both the site and inverter levels, allowing us to evaluate the measurement accuracy by comparing the sensor readings at these two levels. For this purpose, we integrated the power data collected from sensors at the site and inverter levels, which were recorded at 15-minute and 5-minute intervals, respectively. Figure 6 presents an example of this calculation for the library station on August 31, 2022. The Library PV station consists of three inverters: Inverter 1 is connected to 156 PV modules and 78 optimizers, Inverter 2 to 152 PV modules and 76 optimizers, and Inverter 3 to 152 PV modules and 76 optimizers. The integration results for the power data from three inverters were 175.77 kWh, 251.88 kWh, and 213.90 kWh, respectively. The integration result for the power data from the site level was 642.09 kWh. The generation difference refers to the absolute value of the disparity in daily power generation calculated from the two levels. On this day, the power generation data derived from the two levels exhibited a deviation of 0.529 kWh, equivalent to a relative error of 0.08%.

The same calculation was conducted for each day in 37 solar PV plants equipped with panel optimizers. Figure 7 illustrates the daily generation data derived from both site-level and inverter-level measurements. Each point in the scatter plot represents daily generation data, with the x-axis representing the generation integrated from site data and the y-axis representing the generation integrated from inverter data. A 1:1 line is included to emphasize the anticipated agreement between the two datasets. The table within the figure summarizes the percentage of days that fall within specific generation difference ranges (in kWh), revealing that over 60% of days exhibit a difference of less than 0.1 kWh. Over a three-year period, the average daily generation difference across all power stations was 0.34 kWh, with a standard deviation of 2.02 kWh. Our analysis indicates that the measurement difference was less than 1 kWh on more than 92% of the days. Furthermore, the average relative error was 0.32%, which is defined as the absolute value of the difference divided by the smaller of the two calculated daily generation values. These findings confirm a strong consistency between the data calculated at the site and inverter levels, thereby validating the quality of data measurement and recording.

Data missing rate

In addition to data accuracy, the data missing rate is another important indicator of data quality. The missing rate for each data type is calculated as shown in Eq. (1). Table 4 presents an overall assessment of the missing data rates for meteorological and PV generation data over a three-year period. According to the grading system established by Lindig et al.48, data quality is classified into four levels: Grade A, Grade B, Grade C, and Grade D. Our data is classified as Grade A, given that the missing rate is below 10%, indicating high data quality.

Missing data may arise from various factors, including communication failures, equipment malfunctions, and data logging errors. Communication failures between PV inverters and the gateway are typically intermittent and short-lived, often resolving within a few time intervals. Similarly, data logging errors, which occur when the data collection system fails to capture information, also tend to be brief in duration. In contrast, equipment malfunctions, particularly during maintenance activities or power outages, can lead to prolonged periods of missing data, generally lasting several days.

To provide a comprehensive understanding of the missing rates in meteorological data, we categorize our analysis into two distinct categories: planned and unplanned reasons. Planned reasons encompass scheduled maintenance and power outage inspections, which are essential for the optimal functioning of the weather station. In contrast, unplanned reasons pertain to issues such as communication interruptions, data loss, and equipment failures that arise from uncontrollable factors. Figure 8 illustrates the quarterly missing rates of various categories of meteorological data, distinguishing between planned reasons (a) and unplanned reasons (b).

Figure 9 displays the missing rates for different PV stations in each quarter during their respective operating cycles. It is worth noting that 60 power stations were installed and began operating at different times between 2021 and 2023, which is why there are gray areas without values in the figure. The missing rates were calculated using Eq. (1), which determines the missing rate for each variable of a PV station within a specific quarter. The overall average missing rate for the station in that quarter is subsequently derived by averaging the missing rates of all its variables. Photovoltaic (PV) stations without panel-level optimizers possess 2 variables, whereas those equipped with panel-level optimizers possess 19 variables, as detailed in Table 4. This information can be helpful in selecting appropriate solar PV plants for analysis based on the availability of data and data integrity during specific collection periods.

Usage Notes

This dataset reflects the performance of PV systems in Hong Kong, located at approximately 22.3964° N latitude and 114.1095° E longitude. This region has a subtropical climate, with humidity levels averaging over 75% and temperatures ranging from 10°C in winter to above 30°C in summer49. These climate conditions—especially temperature, humidity, and solar irradiance—significantly impact the performance of PV systems, leading to variations in efficiency50. Elevated temperatures can reduce the efficiency of PV panels, while high humidity may lead to dust accumulation, further affecting performance. Since the meteorological and solar PV data are recorded in this specific location, this may limit the generalizability of models trained on this dataset and present additional limitations. Users should consider these limitations and local climatic factors when using our data.

Code availability

An example Python code for querying and retrieving information about PV generation system is available at the dataset’s GitHub page: https://github.com/ZinanLin-Oscar/SPARQL-Example-for-PV-Brick-Model.

References

Olabi, A. & Abdelkareem, M. A. Renewable energy and climate change. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 158, 112111 (2022).

Victoria, M. et al. Solar photovoltaics is ready to power a sustainable future. Joule 5, 1041–1056 (2021).

Alipour, M., Salim, H., Stewart, R. A. & Sahin, O. Residential solar photovoltaic adoption behaviour: End-to-end review of theories, methods and approaches. Renewable Energy 170, 471–486 (2021).

International Energy Agency. Renewables 2019 - Analysis. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/renewables-2019 [Accessed on:15 March 2024].

Das, U. K. et al. Forecasting of photovoltaic power generation and model optimization: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 81, 912–928 (2018).

Zhou, Q., Dong, P., Li, M. & Wang, Z. Analyzing the interactions between photovoltaic system and its ambient environment using cfd techniques: A review. Energy and Buildings 113394 (2023).

Pillai, D. S. & Rajasekar, N. A comprehensive review on protection challenges and fault diagnosis in pv systems. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 91, 18–40 (2018).

Jørgensen, M., Norrman, K. & Krebs, F. C. Stability/degradation of polymer solar cells. Solar energy materials and solar cells 92, 686–714 (2008).

Yuan, R. et al. A synthetic dataset of danish residential electricity prosumers. Scientific Data 10, 371 (2023).

Agee, P., Nikdel, L. & Roberts, S. A measured energy use, solar production, and building air leakage dataset for a zero energy commercial building. Scientific Data 8, 299 (2021).

Nie, Y. et al. SKIPP’D: A sky images and photovoltaic power generation dataset for short-term solar forecasting. Solar Energy 255, 171–179 (2023).

Yao, T. et al. A photovoltaic power output dataset: Multi-source photovoltaic power output dataset with python toolkit. Solar Energy 230, 122–130 (2021).

Pecan Street. Dataport. Available online: https://www.pecanstreet.org/dataport [Accessed on:15 March 2024].

Jordan, D. C. & Kurtz, S. R. Photovoltaic degradation rates-an analytical review. Progress in photovoltaics: Research and Applications 21, 12–29 (2013).

Chine, W., Mellit, A., Pavan, A. M. & Kalogirou, S. A. Fault detection method for grid-connected photovoltaic plants. Renewable Energy 66, 99–110 (2014).

Kim, S.-K., Jeon, J.-H., Cho, C.-H., Kim, E.-S. & Ahn, J.-B. Modeling and simulation of a grid-connected pv generation system for electromagnetic transient analysis. Solar Energy 83, 664–678 (2009).

Balaji, B. et al. Brick: Towards a unified metadata schema for buildings. In Proceedings of the 3rd ACM International Conference on Systems for Energy-Efficient Built Environments, 41–50 (2016).

Halabi, L. M., Mekhilef, S., Olatomiwa, L. & Hazelton, J. Performance analysis of hybrid pv/diesel/battery system using homer: A case study sabah, malaysia. Energy conversion and management 144, 322–339 (2017).

Kumar, S. & Tiwari, G. Life cycle cost analysis of single slope hybrid (pv/t) active solar still. Applied energy 86, 1995–2004 (2009).

Erdil, E., Ilkan, M. & Egelioglu, F. An experimental study on energy generation with a photovoltaic (pv)–solar thermal hybrid system. Energy 33, 1241–1245 (2008).

Yousri, D., Allam, D. & Eteiba, M. B. Optimal photovoltaic array reconfiguration for alleviating the partial shading influence based on a modified harris hawks optimizer. Energy Conversion and Management 206, 112470 (2020).

Chen, H. et al. An opposition-based sine cosine approach with local search for parameter estimation of photovoltaic models. Energy Conversion and Management 195, 927–942 (2019).

Orduz, R., Solórzano, J., Egido, M. Á. & Román, E. Analytical study and evaluation results of power optimizers for distributed power conditioning in photovoltaic arrays. Progress in Photovoltaics: Research and Applications 21, 359–373 (2013).

Rai, A. K., Kaushika, N., Singh, B. & Agarwal, N. Simulation model of ann based maximum power point tracking controller for solar pv system. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells 95, 773–778 (2011).

Hu, J., Xu, Y., Cheng, K. W. & Guerrero, J. M. A model predictive control strategy of pv-battery microgrid under variable power generations and load conditions. Applied Energy 221, 195–203 (2018).

Mellit, A. & Pavan, A. M. A 24-h forecast of solar irradiance using artificial neural network: Application for performance prediction of a grid-connected pv plant at trieste, italy. Solar energy 84, 807–821 (2010).

Dhimish, M., Holmes, V., Mehrdadi, B. & Dales, M. Comparing mamdani sugeno fuzzy logic and rbf ann network for pv fault detection. Renewable energy 117, 257–274 (2018).

Silvestre, S., Chouder, A. & Karatepe, E. Automatic fault detection in grid connected pv systems. Solar energy 94, 119–127 (2013).

Chouder, A. & Silvestre, S. Automatic supervision and fault detection of pv systems based on power losses analysis. Energy conversion and Management 51, 1929–1937 (2010).

Bansal, N., Jaiswal, S. P. & Singh, G. Comparative investigation of performance evaluation, degradation causes, impact and corrective measures for ground mount and rooftop solar pv plants–a review. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments 47, 101526 (2021).

Sánchez-Friera, P., Piliougine, M., Peláez, J., Carretero, J. & Sidrach de Cardona, M. Analysis of degradation mechanisms of crystalline silicon pv modules after 12 years of operation in southern europe. Progress in photovoltaics: Research and Applications 19, 658–666 (2011).

Hong Kong Green Building Council. Hong Kong: Green Building in Action. Available online: https://www.hkgbc.org.hk/eng/resources/publications/HKGBC-Publication/Reports/green-building-in-action/images/Green_Building_in_Action_2019ENG.pdf [Accessed on:15 March 2024].

Google Earth. Satellite Imagery of the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. Available online: https://earth.google.com/web/@22.33747481,114.26360537,116.42738107a,565.16860896d,35y,270.43965637h,0t,0r/data=OgMKATA [Accessed on:15 March 2024].

Yang, B. et al. Novel bio-inspired memetic salp swarm algorithm and application to mppt for pv systems considering partial shading condition. Journal of cleaner production 215, 1203–1222 (2019).

Chu, G., Wen, H., Jiang, L., Hu, Y. & Li, X. Bidirectional flyback based isolated-port submodule differential power processing optimizer for photovoltaic applications. Solar Energy 158, 929–940 (2017).

SolarEdge. Wireless Gateway and Repeater for North America. Available online: https://knowledge-center.solaredge.com/sites/kc/files/se-wireless-gateway-and-repeater-datasheet-na.pdf [Accessed on:15 March 2024].

SMA Solar. SMA Com Gateway. Available online: https://www.sma.de/en/products/monitoring-control/sma-com-gateway [Accessed on:15 March 2024].

SolarEdge. PV Monitoring Platform - Solar Panel Efficiency. Available online: https://www.solaredge.com/en/products/software-tools/monitoring-platform [Accessed on:15 March 2024].

SMA Solar. Sunny Portal Powered by ennexOS. Available online: https://www.sma.de/en/products/monitoring-control/sunny-portal [Accessed on:15 March 2024].

Campbell Scientific. CR10X-2M - Measurement and Control Datalogger with 2 M Additional Memory and Wiring Panel. Available online: https://www.campbellsci.com/cr10x-2m [Accessed on:15 March 2024].

pandas Development Team. pandas.DataFrame.resample — pandas 2.2.2 Documentation. Available online: https://pandas.pydata.org/docs/reference/api/pandas.DataFrame.resample.html [Accessed on:15 March 2024].

Lin, Z. et al. A High-Resolution Three-Year Dataset Supporting Rooftop Photovoltaics (PV) Generation Analytics. Available online: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.m37pvmd99 [Accessed on:15 October 2024].

Noroozian, R., Abedi, M., Gharehpetian, G. & Hosseini, S. Combined operation of dc isolated distribution and pv systems for supplying unbalanced ac loads. Renewable Energy 34, 899–908 (2009).

Batzelis, E. I., Papathanassiou, S. A. & Pal, B. C. PV system control to provide active power reserves under partial shading conditions. IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics 33, 9163–9175 (2018).

Brick Schema. Graph Visualization. Available online: https://viewer.brickschema.org/ [Accessed on:15 March 2024].

European Commission: Joint Research Centre. Standards for the assessment of the environmental performance of photovoltaic modules, power conversion equipment and photovoltaic systems. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2760/89830 [Accessed on:15 March 2024].

The United States Agency for International Development. Photovoltaic system standards. Available online: https://www.usaid.gov/energy/powering-health/technical-standards/photovoltaic-systems [Accessed on:15 March 2024].

Lindig, S. et al. International collaboration framework for the calculation of performance loss rates: Data quality, benchmarks, and trends (towards a uniform methodology). Progress in Photovoltaics: Research and Applications 29, 573–602 (2021).

Siu, L. W. & Hart, M. A. Quantifying urban heat island intensity in hong kong sar, china. Environmental monitoring and assessment 185, 4383–4398 (2013).

Ramli, M. A. et al. On the investigation of photovoltaic output power reduction due to dust accumulation and weather conditions. Renewable Energy 99, 836–844 (2016).

LI-COR Environmental. LI-200R Pyranometer. Available online: https://www.licor.com/env/products/light/pyranometer [Accessed on:15 March 2024].

Campbell Scientific. HMP60-L - Temperature and Relative Humidity Probe. Available online: https://www.campbellsci.cc/hmp60 [Accessed on:15 March 2024].

Campbell Scientific. CS106 - Barometer. Available online: https://www.campbellsci.com/cs106 [Accessed on:15 March 2024].

Belfort Instrument Company. Belfort Instrument Visibility Sensor Manual Model 6400. Available online: https://metone.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Model-6400-Manual-12202016.pdf [Accessed on:15 March 2024].

Campbell Scientific. TE525-L - Rain Gage with 6 in. orifice. Available online: https://www.campbellsci.com/te525-l [Accessed on:15 March 2024].

Campbell Scientific. 85000 - RM Young 2D Ultrasonic Anemometer. Available online: https://www.campbellsci.ca/85000 [Accessed on:15 March 2024].

Acknowledgements

The work described in this paper is substantially supported by a grant from the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China (Project No. C6003-22Y), and by the National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFC3807100).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zinan Lin and Ce Wang managed data curation of the dataset and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. Qi Zhou and Zhe Wang managed raw data collection of the dataset and edited the manuscript. Davis Boyd Bookhart and Marcus Leung-Shea participated in the raw data collection and reviewed the manuscript. Zhe Wang and Davis Boyd Bookhart supervised the research effort and contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, Z., Zhou, Q., Wang, Z. et al. A high-resolution three-year dataset supporting rooftop photovoltaics (PV) generation analytics. Sci Data 12, 63 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04397-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04397-y