Abstract

Browsing histories can be a valuable resource for cybersecurity, research, and testing. Individuals are often reluctant to share their browsing histories online, and the use of personal data requires obtaining signed informed consent. Research shows that anonymized histories can lead to re-identification, nullifying the anonymity promised by informed consent. In this work, we present 500 synthetic browsing histories valid for 50 countries worldwide. The synthetic histories are compiled based on real browsing data using a series of transformation criteria, including website content, popularity, locality, and language, ensuring their validity for the respective countries. Each history maintains the order of webpage accesses and covers a one-month period. The motivation for publishing this dataset arises from the community’s call for browsing histories from different countries for research, development, and education. The published synthetic browsing histories can be used for any purpose without legal restrictions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

There is a common need for large public collections of browsing histories for research, education, and development. However, making a large set of real browsing histories online poses high risks of privacy breaches and data misuse. Therefore, strict legal measures are in place to ensure that personal data are protected. Informed consent must be signed by each participant, which is problematic in large numbers and internationally due to different laws. Informed consent is common to ensure the anonymity of participants. This is an empty promise as individuals can be re-identified from anonymous browsing histories.

Anonymity Questioned

Su et al.1 proved that anonymous browsing histories can be used to re-identify individuals. People commonly post URL links on their social media accounts. URLs posted on a person’s X account (previously known as Twitter) were used as the recommendation set R. The authors assumed that the user had visited the links in the recommendation set before their posting online. Therefore, these URLs are also present in the anonymous user history H. In the experiment carried out, 60 simulated users were identified by their profiles in 52 % of the cases using the maximum likelihood estimate. Other methods tested were the basic intersection size and the Jaccard index. The intersection method linked a person’s history with the recommendation set by most URLs present in | R ∩ H |. The Jaccard index was used to eliminate the effect of the size of the recommendation set | H ∩ R | / | H ∪ R |. The methods resulted in 42 and 13 % of identified users, respectively. The results showed that the maximum likelihood estimate outperformed the simpler methods. Deußer et al.2 showed that generalization to anonymize the data does not work. The authors attempted to re-identify persons from anonymous browsing data by a limited set of URLs known for the individuals. The known URLs may come from shoulder surfing, posted links on social networks, or general knowledge of the person’s browsing behavior. The authors used data from an audience measurement provider in Germany. Over 2.5 k websites and applications were included in the data. The anonymous dataset processed contained about 4.1 M clients, 1.2 k websites and 62 k endpages. The partially known data about the individuals were the webpages visited and time. The results showed that only 2 visited URLs with known access time in minutes are sufficient to link about 50 % of anonymous browsing sessions to individuals. 10 visited URLs are needed to link about 80 % of anonymous browsing sessions. With the URL visit timestamp less known, for example, as an hour or day, the identification was reduced substantially. However, 7 URL visits with the known day access time were needed to identify about 20 % of the anonymous browsing sessions.

Informed Consent Needed

Informed consent is used to protect user privacy. It ensures that individuals who share their personal data are aware of the purpose and risks. Nature Editorials3 stated that research studies based on personal data need informed consent. Personal data is rarely used as originally intended. The outcome of the data processing can vary as unexpected patterns are often discovered. An example is given when phone tracking records were collected. The researchers could not have asked the participants to use their data for a purpose since the purpose was not known at the time of data collection. Therefore, informed consent must be relatively open to comply with unknown purposes that may cover research, education, and development. Furthermore, any participant should be able to withdraw their personal data at any time. This is almost impossible to implement in large amounts of anonymized data, especially when already posted online.

Synthetic History Applications

The synthetic browsing histories in this dataset serve as a privacy-preserving alternative to real browsing data while offering significant potential for various research and testing applications. Synthetic browsing data can be used in cybersecurity research to train and test anomaly detection systems to identify suspicious browsing and overcome privacy restrictions of real-world data4. A specific example is phishing detection, as synthetic histories provide a valuable dataset of valid benign URLs for specific countries5. The benign URLs in the synthetic histories can be used to train phishing detection models. This would allow for tailored phishing detection systems. Another usage could be for the validation of machine learning algorithms, for example, to test web crawling, as the synthetic histories provide local URLs linked to places in countries6. Synthetic histories can also provide insights into global and local web data per country, including categories such as News, Shopping, and Business1,2. On the other hand, synthetic browsing histories cannot be used for behavioral insights by examining individual browsing data, including time-of-access patterns. The reason is that the owners of synthetic histories do not exist. The virtual owners of the histories mimic the behavior of the owner of the original history. The raw data were obtained through a web crawl from Common Crawl7. That means that the web content may be corrupted, retracted, or not accessible. Custom content filtering may be applied to synthetic history entries for specific applications.

Limited Synthetic Web Data

There is limited work on synthetic web usage data. Hofgesang et al.8 proposed a methodology to build synthetic web data generators based on an extensive analysis of five real-world web usage datasets. Their approach emphasized the potential of synthetic data to bridge the gap in Web Usage Mining (WUM) research, where real-world datasets are often inaccessible due to privacy concerns. Their methodology relied on real-world usage patterns to create data generators that approximate actual web interactions. This enables the development of customer profiling and personalization techniques. However, it is limited only to five websites. Our work generates a large-scale dataset of synthetic browsing histories for 50 countries. The related efforts on synthetic data focused on domain-specific applications, including biomedical for assessing machine-learning healthcare software9, finance for predictive trading strategies10, fraud detection for the case of credit cards11, and generic education cases12. Unlike these efforts, our dataset is designed to support a wide range of research fields, including web analytics, recommendation systems, cybersecurity, and ethical AI development. We are using state-of-the-art tools such as Common Crawl to ensure the dataset includes real web data while safeguarding privacy.

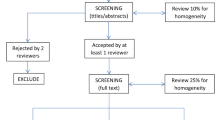

Methods

The synthetic browsing histories for 50 countries are based on a real browsing history. A series of transformation criteria are used to compile the synthetic histories for the respective country. The synthetic histories maintain the original history structure. The website access times in the synthetic histories are randomly shifted from the original history to ensure the privacy of the real history provider. The websites in the synthetic histories remain unchanged when used commonly in both the source and target countries. The website endpages in the synthetic histories are always transformed using the transformation criteria to maintain privacy. The transformation criteria used make each synthetic history valid for the target country. The compiled synthetic histories are verified for their validity in the target country.

Base Algorithm

Algorithm 1 describes the compilation process of the synthetic browsing histories for the target country. The algorithm inputs are:

-

Original browsing history. This is a real browsing history that is used to compile the synthetic browsing histories for countries.

-

Common Crawl data. This data is used to transform the original history website endpages into the synthetic history website endpages. The websites and their endpages are transformed to be valid for the country.

-

Country and world ranked websites. The most visited websites in the world and in the target country are used to transform websites from the original history to the synthetic histories.

-

OpenStreetMap data. The mapping data are used to collect the local websites in the target country for the purpose of transformation of local websites, that is, websites that are not world or country ranked.

-

Website content detection model. This model is used to estimate the content category of the websites in the original history and in the country transformation pools. The content category is used to match the same content-category websites between the original and synthetic histories.

-

Language detection model. The language detection model is used to estimate the language of the websites in the original history and in the country transformation pools. The language is used to match the equivalent websites between the original history and the synthetic histories.

-

Target countries. This is the list of countries for which the synthetic browsing histories are compiled.

Algorithm 1

Algorithm for compilation of synthetic browsing histories for countries.

Algorithm 1 lines 3-5 are explained in detail in the section ‘Target country data pools’. Lines 8-13 and 18-23 are explained in the section ‘Data classification’. Lines 28-43 and 48-54 are explained in detail in the section ‘Synthetic history transformation’.

Target Country Data Pools

The country data pools contain websites and their endpages visited by users in the target country. These websites come from the country ranked websites, which are the top visited websites in the country. Country local websites are also included in the data pools. Local websites are visited by users in the country. Table 1 lists the created data pools for 50 target countries. The particular data sources used are the following:

-

The country global websites are taken from DataForSEO13. DataForSEO provides lists of the top websites visited by users in the target countries.

-

The country local websites are extracted from the mapping data provided by OpenStreetMap14. Websites related to places in the target country are used.

-

The website endpages are compiled from Common Crawl7. Common Crawl provides extensive datasets of monthly collections from the whole Internet. The website endpages provided by Common Crawl from the same time range as the original history were used to ensure their time validity in the created country data pools.

Data Classification

The classification is used for the website transformation from the original history into the synthetic history for the target country. The websites in the created country data pools and in the original history are classified for this reason. The classification process is the following:

-

The websites are classified into top world ranks of 10, 100, 1000, 10000, 100000, and 1000000. The top 10 rank class means that the website is present in the 10 most world visited websites. The 1000000 rank means that the website is present in the 1000000 most world visited websites. A website that is not ranked is marked as −1. Majestic Million15 is used as the source data for the world rank classification.

-

The websites are classified into top country ranks of 10, 100, and 500. The top 10 rank class means that the website is present in the 10 most visited websites in the country. The top 500 rank class means that the website is present in the 500 most visited websites in the country. A website that is not ranked is marked as –1. DataForSEO13 is used as the source data for the country rank classification.

-

The website content is classified into the following categories: Business, Generic, News, Shopping, and Society. A machine-learning model by Lugeon et al.16 is used for content classification of the websites. Minor classes are joined in major groups. For example, the classes Sports and Games are covered by the major class Society. This ensures representative records for each group.

-

The website language is estimated using a detection library provided by Stahl, P.17. The languages used for the target countries are the following: Hindi, Slovene, Turkish, Japanese, Bulgarian, Malay, Czech, Danish, Arabic, Nynorsk, Tamil, Polish, Thai, English, Irish, Serbian, Ukrainian, Hungarian, Slovak, Urdu, Vietnamese, Estonian, Swedish, Greek, Romanian, Croatian, Dutch, Latvian, Italian, Spanish, French, Finnish, Lithuanian, German, Portuguese, and Hebrew.

-

The website endpages are classified into classes of 1, 25, 50 by the endpage path length. The first class is used for the root endpages of the websites. An endpage path longer than 50 is marked as –1.

Synthetic History Transformation

A series of transformation criteria are used to compile the synthetic browsing histories for the target countries. The websites are first transformed, followed by their endpages. The access times in the synthetic histories are randomly shifted to mask the original history timestamps. The order of the webpage accesses is maintained as the original. Search websites in the original history are not processed, e.g., google.com. The original history is exported from a Google user account using the Google Takeout18 service available at https://takeout.google.com/settings/takeout in JSON format. Original history records are limited to a period of one month. The transformation steps are applied to the original history entries as follows:

-

1.

Maintain the original history website if it is listed in the top country ranked websites (most visited websites) for the target country.

-

2.

Filter websites from the same content-category in the target country pool as the original history website.

-

3.

Filter websites from the same country rank in the target country pool as the original history website.

-

4.

Filter websites from the same world rank category pool as the original history website.

-

5.

Filter websites by the target country official language(s) pool or English.

-

6.

Shift the access time of the original history endpage by a random value. The websites and their endpages access order are maintained as original.

-

7.

Maintain the original history website if it is the root page.

-

8.

Filter website endpages from the same path bin in the target country pool as the original website endpage.

-

9.

Sample a result if there are more outputs from the matching criteria.

Example History Record Transformation

An example transformation for a synthetic history record is presented. The original history record is https://www.bohemiapc.cz/pocitace-notebooky-prislusenstvi/komponenty/pameti/pameti-ddr5-pc/ with the access time 2024-11-29 20:42:33.421201. The target country for the transformation of the history record is Germany. The example processing steps refer to the pseudo-code lines in Algorithm 1. We do not skip lines with code structure to provide better reference to the algorithm.

-

1.

Pseudo code line 27: This is the first line of original history transformation. The original history is iterated and the website record bohemiapc.cz is processed.

-

2.

Pseudo code line 28: The original website bohemiapc.cz is checked for its presence in the target country ranked websites.

-

3.

Pseudo code line 29: The condition about the website presence in the target country ranked websites is not met. The action of maintaining the original website in the synthetic history is not processed.

-

4.

Pseudo code line 30: The original website bohemiapc.cz content category is checked. The original website content category is ‘Shopping’. There are websites with the same content category in the target country pool of Germany.

-

5.

Pseudo code line 31: Websites with the same content category of ‘Shopping’ are filtered from the target country pool.

-

6.

Pseudo code line 32: The original website bohemiapc.cz country rank is checked. The original website does not belong to the top visited websites in the country. It is therefore not a country ranked website.

-

7.

Pseudo code line 33: The condition about the website presence in the top country visited websites is not met. The action of filtering websites with the same country rank from the target country pool is not processed.

-

8.

Pseudo code line 34: Code structure line.

-

9.

Pseudo code line 35: The original website bohemiapc.cz world rank is checked. The original website does not belong to the top word visited websites. It is therefore not a world ranked website.

-

10.

Pseudo code line 36: The condition about the website presence in the top world visited websites is not met. The action of filtering websites with the same world rank from the target country pool is not processed.

-

11.

Pseudo code line 37: Code structure line.

-

12.

Pseudo code line 38: The original website bohemiapc.cz is checked for language. The result is ‘CES’. This language does not match the target country language, which is ‘DEU’.

-

13.

Pseudo code line 39: The condition about the website same language used in the target country is not met. The action of filtering the websites with the same language from the target country pool is not processed.

-

14.

Pseudo code line 40: Code structure line.

-

15.

Pseudo code line 41: The original website language is not considered and the language of the target country is used. The target country pool contains websites only with the target country languages.

-

16.

Pseudo code line 42: Code structure line.

-

17.

Pseudo code line 43: A website from the filtered results of the target country pool is sampled. The result is the website https://www.berndwolf.de.

-

18.

Pseudo code line 44: Code structure line.

-

19.

Pseudo code line 45: Code structure line.

-

20.

Pseudo code line 46: Code structure line.

-

21.

Pseudo code line 47: The original website endpages are iterated and the endpage pocitace-notebooky-prislusenstvi/komponenty/pameti/pameti-ddr5-pc is processed.

-

22.

Pseudo code line 48: The access time 2024-11-29 20:42:33.421201 is shifted by a random value to 2024-11-29 20:44:31.221766 to preserve privacy of the original history record.

-

23.

Pseudo code line 49: The endpage pocitace-notebooky-prislusenstvi/komponenty/pameti/pameti-ddr5-pc is not a root page of the website.

-

24.

Pseudo code line 50: The condition about the root page is not met. The action of maintaining the endpage is not processed.

-

25.

Pseudo code line 51: The original endpage pocitace-notebooky-prislusenstvi/komponenty/pameti/pameti-ddr5-pc is checked for the path bin. The result is –1. There are websites with the same path bin in the target country pool.

-

26.

Pseudo code line 52: Endpages with the same path bin are filtered from the target country pool.

-

27.

Pseudo code line 53: Code structure line.

-

28.

Pseudo code line 54: An endpage from the filtered results in the target country pool is sampled. The result endpage is antoinette-ketten-mit-anhaenger-sterlingsilber-925-granat-rot.

The final transformation result for the original history record https://www.bohemiapc.cz/pocitace-notebooky-prislusenstvi/komponenty/pameti/pameti-ddr5-pc with the access time 2024-11-29 20:42:33.421201 is the synthetic history record https://www.berndwolf.de/antoinette-ketten-mit-anhaenger-sterlingsilber-925-granat-rot with access time 2024-11-29 20:44:31.221766 valid for Germany.

Data Records

The synthetic browsing histories are deposited on Figshare19. Table 2 describes the records of the published synthetic browsing histories. The core records are the access time and the URL. The extended records are the metadata of the original history used to compile the synthetic history record. Table 3 gives an overview of the values of each record. Table 4 shows the number of synthetic history records in the target countries. There are 10 synthetic histories compiled for each country.

Table 5 shows sample values of a synthetic history for Slovakia. Extended samples of synthetic histories per country are available on GitHub20. Extended samples are present for each of 500 synthetic histories.

Technical Validation

The synthetic histories are technically validated using a series of verification tests. They are verified to contain websites commonly visited by users in the target countries. An empirical complementary cumulative distribution of the synthetic history websites among the country top visited websites illustrates their expected distribution. The content categories Business, Generic, News, Shopping, and Society are checked to be present in the synthetic histories for each country. An empirical complementary cumulative distribution of the transformed original history records shows that almost all the original history records were successfully transformed. The consistency in synthetic histories between countries is also verified.

Figure 1 shows the percentage of synthetic history websites that are among the top websites visited by users in the respective country. The results show that the synthetic histories contain the top country websites in a proportion close to that of the original history, which is 52 %. The subtle differences between the synthetic histories are due to the transformation criteria. Figure 2 shows the empirical complementary cumulative distribution P(X > x) = 1 − P(X ≤ x) of the synthetic history records in the top visited websites in each country. The results show that the synthetic histories are present in the top 10, 100, and 500 visited websites in the country. The complementary cumulative distribution decreases with each top list, confirming the expected behavior.

Table 6 shows the distribution of the website content categories in the synthetic histories. The results show that all categories are present in the synthetic histories for the countries. Furthermore, the category records of Business, Generic, News, Shopping, and Society are consistent between the countries.

Figure 3 shows the empirical complementary cumulative distribution of the transformed original history records into the synthetic histories. The curve shows that the vast majority of the original history records was successfully transformed. The small number of records that could not be transformed was caused by their unsuccessful language detection. Figure 4 shows the consistency of the successfully transformed synthetic history records in the countries. The results show that the number of transformations is consistent across the countries with insignificant differences due to language detection.

Code availability

We publish a pseudo-algorithm that describes the transformation of the original history into the synthetic histories for the target countries. The form of the pseudo-algorithm ensures that personal data ethics are not violated. The pseudo-algorithm is described in detail to allow code implementation on original browsing histories. Furthermore, we also provide extended samples20 of synthetic browsing histories for better visibility and understanding21. Extended samples are provided for each of 500 synthetic histories. The authors offer to provide additional synthetic browsing histories based on their private original history. More synthetic browsing histories can be compiled in a reasonable number for the target country. The published synthetic browsing histories are available under the MIT License.

References

Su, J., Shukla, A., Goel, S. & Narayanan, A. De-anonymizing Web Browsing Data with Social Networks. In WWW ’17: Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on World Wide Web, 1261–1269 (ACM, 2017).

Deußer, C., Passmann, S. & Strufe, T. Browsing Unicity: On the Limits of Anonymizing Web Tracking Data. In IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), 777–790 (IEEE, 2020).

Editorials. Digital-data studies need consent. Nature 572 (2019).

Peng, J., Kim-Kwang, R. & Ashman, H. User profiling in intrusion detection: A review. Journal of Network and Computer Applications 72, 14–27 (2016).

Krishna, A., Jose, B., Anilkumar, K. & Lee, O. Phishing Detection using Machine Learning based URL Analysis: A Survey. International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology 9, 156–161 (2021).

Owoc, M. & Weichbroth, P. Validation model for discovered web user navigation patterns. In IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology, 38–52 (Springer, 2014).

Common Crawl Foundation. Common Crawl. [Online]. Available: https://commoncrawl.org/overview. Accessed: Nov 23, 2024 (2024).

Hofgesang, P. & Patist, P. On modelling and synthetically generating web usage data. In IEEE/WIC/ACM International Conference on Web Intelligence and Intelligent Agent Technology, 98–102 (IEEE, 2008).

Tucker, A., Wang, Z., Rotalinti, Y. & Myles, P. Generating high-fidelity synthetic patient data for assessing machine learning healthcare software. npj Digital Medicine 3 (2020).

Carvajal-Patino, D. & Ramos-Pollan, R. Synthetic data generation with deep generative models to enhance predictive tasks in trading strategies. Research in International Business and Finance 62 (2022).

Strelcenia, E. & Prakoonwit, S. Generating Synthetic Data for Credit Card Fraud Detection Using GANs. In International Conference on Computers and Artificial Intelligence Technologies (CAIT) (IEEE, 2022).

Singh, P., Necholi, A. & Moreno, W. Synthetic Data Generation for Engineering Education: A Bayesian Approach. In IEEE 3rd International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies on Education & Research (ICALTER) (IEEE, 2023).

DataForSEO. Discover the Top Websites Ranking. [Online]. Available: https://dataforseo.com/free-seo-stats/top-1000-websites. Accessed: Apr 9, 2024 (2024).

OSM contributors. OpenStreetMap and the Overpass API. [Online]. Available: https://dev.overpass-api.de/overpass-doc/en/preface/preface.html. Accessed: Apr 9, 2024 (2024).

Majestic-12 Ltd. The Majestic Million. [Online]. Available: https://majestic.com/reports/majestic-million. Accessed: Apr 9, 2024. (2024).

Lugeon, S., Piccardi, T. & West, R. Homepage2vec: Language-agnostic website embedding and classification. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (2022).

Stahl, P. lingua-py. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/pemistahl/lingua-py. Accessed: Apr 10, 2024. (2024).

Google Ireland Limited. How to download your Google data. [Online]. Available: https://support.google.com/accounts/answer/3024190. Accessed: Dec 3, 2024 (2024).

Komosny, D. Synthetic Browsing History. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27979439. Accessed: Dec 6, 2024. (2024).

Komosny, D. Extended Samples of Synthetic Browsing Histories with Code. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/komosny/synthetic-browsing-history. Accessed: Dec 6, 2024. (2024).

Candela, G. et al. A checklist to publish collections as data in GLAM institutions. Global Knowledge, Memory and Communication https://doi.org/10.1108/gkmc-06-2023-0195 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The following notable Python modules were used in this work: lingua-py https://github.com/pemistahl/lingua-py and homepage2vec https://github.com/epfl-dlab/Homepage2vec. Data from these resources were used in this work: The pools of local websites in the countries were obtained from OpenStreetMap openstreetmap.org/copyright. The website global rank data were obtained from Majestic https://majestic.com/. The website country rank data were obtained from DataForSEO https://dataforseo.com/. The pools of endpages for the websites were obtained from Common Crawl https://data.commoncrawl.org/. The specific use of each resource is referenced in the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.K. proposed the idea and conceived the experiments. D.K., S.R., and M.A. analyzed the results and verified the browsing histories for the countries. D.K., S.R., and M.A. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and agreed on the manuscript for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Komosny, D., Rehman, S.U. & Ayub, M.S. Synthetic Browsing Histories for 50 Countries Worldwide: Datasets for Research, Development, and Education. Sci Data 12, 128 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04407-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04407-z