Abstract

Rosa hugonis is widely distributed in the Hengduan Mountains, Qinling Mountains, and northern China. It is an important candidate species for ecological restoration, given its good adaptability. Here, we present the first high-quality chromosome-level assembly of R. hugonis based on HiFi reads and Hi-C data. The sequencing data were then assembled onto seven pseudochromosomes of R. hugonis. The genome sizes of R. hugonis is 337.92 Mb, with contig N50 length of 26.84 Mb. We annotated 36,218 protein-coding genes in R. hugonis. In summary, the high-quality genome sequences of R. hugonis provide a genetic roadmap for the study of its genetics and species relationships. This will facilitate future genomic comparative studies across more species within Rosa.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

The genus Rosa belongs to Rosaceae and comprises 150–200 species widely distributed in the temperate and subtropical regions of the northern hemisphere1,2. Roses are well-known for their remarkable ornamental value in horticulture, for example R. chinensis, which serve as important parent sources for modern ornamental rose varieties3. In addition, roses are rich in essential oils and other bioactive compounds such as tannins, flavonoids, and phenolic acids4,5,6,7,8,9, suggesting that roses possess widely application in the food, cosmetics, and pharmaceutical industries. As so far, only a number of rose genomes have been sequenced and reported, include eight horticultural varieties: R. rugosa10,11, R. chinensis ‘Chilong Hanzhu’12, R. chinensis ‘Old Blush’3, R. chinensis ‘Samantha’13, R. wichuraiana ‘Basye’s Thornless’14, R. chinensis15, R. multiflora16, R. gigantea17, and two wild species: R. roxburghii and R. sterilis18. The lack of high-quality reference genomes has limited in-depth research on the breeding, cultivation, and utilization of wild Rosa species.

Rosa hugonis Hemsl. (Fig. 1) is a perennial shrub widely distributed across many provinces in western and northern China2. The study shown that R. hugonis has retention effects on atmospheric suspended particles, suggesting its potential ability in air purification19. The strong ecological adaptability and population renewal ability of R. hugonis have been proven in some studies, indicating that it is a suitable species for the restoration of dry valleys20,21. With strong adaptability to nutrient-poor and arid environments, study have shown that R. hugonis is a suitable rootstock for grafting with roses22. The main components of the fragrance in R. hugonis petals have been shown to originate from 40 different organic compounds23. Recently, the petal extracts of R. hugonis (primarily phenolic compounds) have been shown to have neuroprotective effects24. In summary, R. hugonis holds significant potential for applications in ecological restoration, horticultural breeding, and compound development and utilization. However, a high-quality genome for R. hugonis is still missing, which has hindered the progress of further research.

In this study, we report the first chromosome-level genome assembly of R. hugonis. The assembled genome size of R. hugonis was 337.96 Mb using PacBio single-molecular DNA sequencing technology25, and the contig N50 was 28.14 Mb. To obtain the high-quality genome assembly at the chromosome level, high-throughput chromatin conformation capture (Hi-C)26 was used and the contigs were clustered into seven pseudochromosomes, which corresponds to 99.68% of the total contig length. The final assembled genome size of R. hugonis was 337.92 Mb with the scaffold N50 length of 26.84 Mb. A total set of 36,218 putative protein-coding genes (PCGs) were predicted in R. hugonis, among which, 93.73% were annotated to the publicly available database. The chromosome-level genome assembly of R. hugonis set up a valuable platform for elucidating mechanisms of adaptation for surviving adverse environments and for advancing its development and utilization.

Methods

Plant materials and polyploidy estimation

The cultivated materials of R. hugonis were moved from the wild into greenhouse of Chengdu Institute of Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CIB, CAS). The materials from Maoxian County, Sichuan Province (latitude: 103.692792, longitude: 31.520581, altitude: 1,625 m). The vouchers of specimens were deposited in the herbarium CDBI.

We used new born roots to observe the chromosome numbers of R. hugonis. The roots were collected and immersed in a 0.002 M/L aqueous solution of 8-hydroxyquinoline at a constant temperature of 15 degrees Celsius for 3–4 h, then fixed in Carnoy’s solution for 0.5–24 h, macerated in 1 N HCl at 60°C for 5 min., and then squashed in Carbol fuchsin. Observation and photography of cells in the metaphase of mitosis were conducted using Olympus microscope (Japan, BX43). The result showed that R. hugonis is diploid with 14 chromosomes in mitotic metaphase. (Fig. 2).

DNA extraction and sequencing

Fresh young leaves were collected from a mature R. hugonis plant and were sent to Berry Genomics Company (Beijing, China) for genome sequencing. For PacBio sequencing, high-quality genomic DNA was extracted from fresh leaves using the CTAB method27. DNA quality and concentration were assessed using NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific), agrose gel electrophoresis and Qubit 3.0 Fluorometer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The library of 15 kb was constructed using a SMRTbell Express Template Prep Kit 2.0 (Pacific Biosciences, CA, USA). We used the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer system to evaluate the size and quality of the library. The library was sequenced using a single 8 M SMAT Cell on the PacBio Sequel II platform (Pacific Biosciences, CA, USA). The PacBio SMRT-Analysis Link (https://www.pacb.com) was used for the quality control of the raw polymerase reads. For Hi-C sequencing, extracted DNA was first crosslinked with 40 ml of 2% formaldehyde solution to capture interacting DNA segments. Subsequently, the crosslinked DNA was digested with the DpnII restriction enzyme, and libraries were constructed and sequenced using an Illumina Novaseq 6000 platform with paired-end 150 bp reads. For transcriptome sequencing, fresh tissue samples including stem, leaf, and flower were collected from the same R. hugonis plant and frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately. Total RNA was subsequently extracted using the RNAprep Pure Polysaccharide Polyphenols Plant Total RNA Extraction Kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China). The concentration and quality of RNA were assessed using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA) and a Bioanalyzer 2100/4200 system (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA). Subsequently, paired-end cDNA libraries were prepared from mRNA enriched with Oligo-dT magnetic beads, fragmented, circularized, and then subjected to PE150 sequencing on the Illumina Novaseq 6000 platform.

Genome assembly and quality control

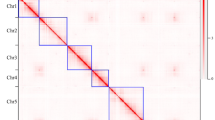

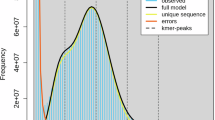

Hifiasm v0.15.228 software was applied to generate the draft assembly with CCS reads. For the cleaning of heterozygous contigs, we used minimap2 v2.1329 to align the CCS reads to the assembled genome sequences. Subsequently, the heterozygous contigs were removed based on the coverage distribution of the aligned reads and their alignment scores. For the removal of pseudo contigs, we used minimap2 aligned the CCS reads to genome sequences that have removed heterozygous contigs. Based on the alignment results, the contigs with an average coverage depth of less than 5 × were removed, which are considered potential pseudo contigs. After polished, the contig assembly had a total size of ~337.96 Mb, with a contig N50 value of 28.14 Mb (Table 1). Next, in order to construct a high-quality reference genome, the Hi-C library was prepared using the method described previously30,31. We removed the low-quality reads to avoid reads with artificial bias. The filtered Hi-C reads were aligned to the initial draft genome by BWA software which was integrated into Juicer v1.6.232 software. Only uniquely mapped and validated paired-end reads were used to assembly by 3D-DNA pipeline33. Juicebox v1.9.834 were used to manually order the scaffolds to get the final chromosome assembly. Contact maps were plotted with HiCExplorer v3.335. We obtained 49 high-quality contigs (contig N50 = 26.84 Mb), with a total assembly size of 337.92 Mb and anchored 331.31 Mb onto seven pseudochromosomes using Hi-C data (Table 2; Fig. 3).

Genome assembly and completeness were assessed using the conserved genes of in BUSCO (Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs) assessments based on the embryophyta_odb10 database36. A total of 98.6% (94.7% single-copy BUSCOs) completeness was revealed by the analysis (Table 1). In the same time, the CCS short-reads were mapped to the assembled genome sequence using minimap2 v2.13 with default settings. A mapping rate of 99.96% was estimated by the analysis (Table 1).

Genome annotation

We used MITE-Hunter v1.037 to identify the mini-inverted repeat transposable elements (MITEs) which were widely present in the genome. LTRharvest38 and LTR Finder v1.0739 were used to detected the long terminal repeated sequences (LTRs) in the genome and LTR retriever v2.8.240 was used to integrated the prediction results of two software mentioned above. For homolog evidence, RepeatMasker v4.1.041 was used to search the genome sequence for the sequence similar to the known repetitive sequence in the repetitive sequence database RepBase (http://www.girinst.org/repbase) to obtain the known repetitive sequence in the target genome. RepeatModeler v2.042 was used to de novo identify other repetitive sequences with repeat-masked genome. The result showed that R. hugonis genome comprises 48.8% repetitive sequences totaling 164.9 Mb, with LTRs and DNA transposons constituting 34.37% and 5.11%, respectively. For LTRs, Gypsy and Copia are the two most numerous types with 11.17% and 10.67%, respectively.

A comprehensive strategy combing ab initio prediction, protein-based homology searches, and RNA sequencing was used for gene structure annotation. AUGUSTUS v3.2.243, SNAP v6.044, Glimmerhmm v3.0.445 and GeneMark-ESSuite v4.5746 were used to predict gene structure in the repeat-masked genome. GeMoMa v1.7.147 was used to perform homology prediction and then obtain exon and intron boundary information based on the comparison between the transcript and the genome. HISAT2 v2.0.648 was used to align RNA-Seq reads to the genome sequence and Cufflinks49 was used to assemble transcripts for obtaining the full-length transcript sequences. PASA vr2014041750 software was used to predict the open reading frame (ORF) based on the obtained full-length transcript sequence. EVidenceModeler v1.1.151 was used to integrate the above prediction results, and UTR and other variable cut annotation was predicted by PASA software. A total of 36,218 predicted gene modules were obtained (Table 3). The Circos tool (http://www.circos.ca) was utilized to visualize gene density, GC content, repeat content on each pseudochromosome (Fig. 4).

For the functional annotation, all PCGs were aligned to three integrated protein sequence databases: NR (v202108, ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/db/FASTA/nr.gz) and SwissProt (v1.7.1, https://ftp.uniprot.org/pub/databases/uniprot/current_release/knowledgebase/complete/uniprot_sprot.fasta.gz) using BLAST v2.2.3152 with e-value ≤ 1e-5, eggNOG (http://eggnog5.embl.de/#/app/home) using eggNOG-mapper v2.0.153 with default settings. Protein domains were annotated by InterPro and the Gene Ontology (GO) terms for each gene were obtained from the corresponding InterPro entry. The pathways in which the genes might be involved were assigned by BLAST v2.2.31 against the KEGG databases (https://www.genome.jp/kegg/brite.html). Among all the PCGs, 33,946 genes (93.73%) were functionally annotated to at least one database, and 4,959 genes (13.69%) were annotated in all five databases (Fig. 5).

The software of tRNAscan-SE v2.054 was used to predict tRNA in the genome sequence. The Rfam database was used to annotate other types of ncRNA by BLAST v2.2.31. We identified 702 rRNA, 669 tRNA, 105 miRNA, 194 snRNA and 470 snoRNA in R. hugonis assembly.

Data Records

The data that support the findings of this study have been deposited into the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under Bioproject PRJNA118110955 and CNGB Sequence Archive (CNSA)56 of China National GeneBank DataBase (CNGBdb)57 with accession number CNP000555858,59,60,61,62,63. The chromosome-level genome assembly has been deposited at CNGB under accession number CNA013850864 and GenBank under the accession JBJCIR00000000065.

Technical Validation

The quality of the R. hugonis genome assembly was evaluated using three methods. First, the interaction contact patterns in the Hi-C heatmap are organized around the main diagonal, directly supporting the accuracy of the chromosome assembly. Secondly, the BUSCO assessment of the genome assembly indicated a high level of completeness, with 98.6% (94.7% single-copy BUSCOs) complete matches to the embryophyta_odb10 dataset. Finally, CCS shorter-reads mapping was employed to assess assembly quality and the results showed a mapping rate of 99.96%, suggesting that the genome is of high quality.

The annotations of genome repetitive sequences, genome structure, ncRNAs, and gene functions were performed using transcript-based, de novo, and homology-based prediction methods. These methods resulted in the prediction of 36,218 gene models. Through alignment with public protein databases, functional annotations are available for 93.73% of the genes (33,946).

Code availability

All software and pipelines were conducted accordance with the manuals and protocols of publicly available tools. No custom code was used in this study.

References

Ku, T.C. & Robertson, K.R. in Flora of China Vol. 9 (eds. Wu, C.Y., Raven, P.H.) pp. 339–381 (Science Press/Missouri Botanical Garden Press, Beijing/St, Louis, 2003).

Lu, L.T., Ku, T.C., Kuan, K.C., Li, C.L. in Flora Reipublicae Popularis Sinicae Vol. 37 (eds. Yü, T.T., Wu, C.Y.) pp. 1–516 (Science Press, Beijing, 1985).

Raymond, O. et al. The Rosa genome provides new insights into the domestication of modern roses. Nature Genetics 50, 772–777 (2018).

Czyzowska, A. et al. Polyphenols, vitamin C and antioxidant activity in wines from Rosa canina L. and Rosa rugosa Thunb. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 39, 62–68 (2015).

Liu, M. H. et al. Chemical analysis of dietary constituents in Rosa roxburghii and R. sterilis fruits. Molecules 21, 1204 (2016).

Chang, S. W. et al. New depsides and neuroactive phenolic glucosides from the flower buds of rugosa rose (Rosa rugosa). Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 67, 7289–7296 (2019).

Mileva, M. et al. Rose flowers—a delicate perfume or a natural healer? Biomolecules 11, 127 (2021).

Wang, L. T. et al. Botanical characteristics, phytochemistry and related biological activities of Rosa roxburghii tratt fruit, and its potential use in functional foods: A review. Food & Function 12, 1432–1451 (2021).

Li, H. et al. Physicochemical, biological properties, and flavour profile of Rosa roxburghii Tratt, Pyracantha fortuneana, and Rosa laevigata Michx fruits: A comprehensive review. Food Chemistry 366, 130509 (2022).

Chen, F. et al. A chromosome-level genome assembly of rugged rose (Rosa rugosa) provides insights into its evolution, ecology, and floral characteristics. Horticulture Research 8, 1–13 (2021).

Shang, J. Z. et al. Evolution of the biosynthetic pathways of terpene scent compounds in roses. Current Biology 34, 3550–3563 (2024).

Zhang, X. et al. Haplotype-resolved genome assembly of the diploid Rosa chinensis provides insight into the mechanisms underlying key ornamental traits. Molecular Horticulture 4, 14 (2024).

Zhang, Z. et al. Haplotype-resolved genome assembly and resequencing provide insights into the origin and breeding of modern rose. Nature plants 10, 1659–1671 (2024).

Zhong, M. C. et al. Rose without prickle: genomic insights linked to moisture adaptation. National Science Review 8, 1–12 (2021).

Hibrand Saint-Oyant, L. et al. A high-quality genome sequence of Rosa chinensis to elucidate ornamental traits. Nature Plants 4, 473–484 (2018).

Nakamura, N. et al. Genome structure of Rosa multiflora, a wild ancestor of cultivated roses. DNA Research 25, 113–121 (2018).

Zhou, L. et al. Multi-omics analyzes of Rosa gigantea illuminate tea scent biosynthesis and release mechanisms. Nature Communication 15, 8469 (2024).

Zong, D. et al. Chromosomal-scale genomes of two Rosa species provide insights into genome evolution and ascorbate accumulation. Plant Journal 117, 1264–1280 (2024).

Shi, S. et al. Retention of atmospheric particles by local plant leaves in the mount Wutai scenic area, China. Atmosphere 7, 104 (2016).

Zhou, Z. Q. et al. Differences in growth and reproductive characters of Rosa hugonis in the dry valley of the upper Minjiang River, Sichuan. Acta Ecologica Sinica 28, 1820–1828 (2008).

Zhou, Z. Q. et al. Capability and li mitation of regeneration of Rosa hugonis and R. soulieana in the dry valley of the upper Minjiang River. Acta Ecologica Sinica 29, 1931–1939 (2009).

Epping, J. E. Spotlight on shrub roses. American Nurseryman 170, 27–31 (1989).

Zhao, X. Y. et al. Studies on chemical compounds of the essential oil from flowers of Rosa hugonis Hemsl. Acta Botanica Boreali-Occidentalia Sinica 14, 154–156 (1994).

Zhang, X. et al. Phenolic compounds from the flowers of Rosa hugonis Hemsl. and their neuroprotective effects. Phytochemistry 208, 113589 (2023).

Eid, J. et al. Real-time DNA sequencing from single polymerase molecules. Science 323, 133–138 (2009).

Lieberman-Aiden, E. et al. Comprehensive mapping of long-range interactions reveals folding principles of the human genome. Science 326, 289–293 (2009).

Doyle, J. J. & Doyle, J. L. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochemical bulletin 19, 11–15 (1987).

Cheng, H. Y. et al. Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly with phased assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nature Methods 18, 170–175 (2021).

Li, H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 34, 3094–3100 (2018).

Rao, S. S. et al. A 3D map of the human genome at kilobase resolution reveals principles of chromatin looping. Cell 159, 1665–1680 (2014).

Xie, T. et al. De Novo plant genome assembly based on chromatin interactions: a case study of Arabidopsis thaliana. Molecular Plant 8, 489–492 (2015).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicer provides a one-click system for analyzing loop-resolution Hi-C experiments. Cell Systems 3, 95–98 (2016).

Dudchenko, O. et al. De novo assembly of the Aedes aegypti genome using Hi-C yields chromosome length scaffolds. Science 356, 92–95 (2017).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicebox provides a visualization system for Hi-C contact maps with unlimited zoom. Cell Systems 3, 99–101 (2016).

Wolff, J. et al. Galaxy HiCExplorer 3: a web server for reproducible Hi-C, capture Hi-C and single-cell Hi-C data analysis, quality control and visualization. Nucleic Acids Research 48, W177–W184 (2020).

Seppey, M., Manni, M. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness. Methods in Molecular Biology 1962, 227–245 (2019).

Han, Y. J. & Wessler, S. R. MITE-Hunter: a program for discovering miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements from genomic sequences. Nucleic Acids Research 38, e199 (2010).

Ellinghaus, D., Kurtz, S. & Willhoeft, U. LTRharvest, an efficient and flexible software for de novo detection of LTR retrotransposons. BMC Bioinformatics 9, 18 (2008).

Xu, Z. & Wang, H. LTR_FINDER: an efficient tool for the prediction of full-length LTR retrotransposons. Nucleic Acids Research 35, W265–W268 (2007).

Ou, S. J. & Jiang, N. LTR_retriever: A highly accurate and sensitive program for identification of long terminal repeat retrotransposons. Plant Physiology 176, 1410–1422 (2017).

Chen, N. S. Using RepeatMasker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Current Protocols in Bioinformatics 4, 4.10 (2004).

Flynn, J. M. et al. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 117, 9451–9457 (2020).

Stanke, M. & Morgenstern, B. AUGUSTUS: a web server for gene prediction in eukaryotes that allows user-defined constraints. Nucleic Acids Research 33, W465–W467 (2005).

Ian, K. Gene finding in novel genomes. BMC Bioinformatics 5, 59 (2004).

Majoros, W. H., Pertea, M. & Salzberg, S. L. TigrScan and GlimmerHMM: two open sources ab initio eukaryotic gene-finders. Bioinformatics 20, 2878–2879 (2004).

Lomsadze, A., Burns, P. D. & Borodovsky, M. Integration of mapped RNA-Seq reads into automatic training of eukaryotic gene finding algorithm. Nucleic Acids Research 15, e119 (2014).

Keilwagen, J., Hartung, F. & Grau, J. GeMoMa: Homology-based gene prediction utilizing intron position conservation and RNA-seq data. Methods in Molecular Biology 1962, 161–177 (2019).

Kim, D., Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nature Methods 12, 357–360 (2015).

Trapnell, C. et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nature Biotechnology 28, 511–515 (2010).

Haas, B. J. et al. Improving the Arabidopsis genome annotation using maximal transcript alignment assemblies. Nucleic Acids Research 31, 5654–5666 (2003).

Haas, B. J. et al. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the program to assemble spliced alignments. Genome Biology 9, R7 (2008).

Camacho, C. et al. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 10, 421 (2009).

Cantalapiedra, C. P. et al. eggNOG-mapper v2: Functional Annotation, Orthology Assignments, and Domain Prediction at the Metagenomic Scale. Molecular Biology and Evolution 38, 5825–5829 (2021).

Lowe, T. M. & Eddy, S. R. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Research 25, 955–964 (1997).

NCBI Squence Read Archive. https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP542710 (2024).

Guo, X. Q. et al. CNSA: a data repository for archiving omics data. Database (Oxford) 2020, 1–6 (2020).

Chen, F. Z. et al. CNGBdb: China National GeneBank DataBase. Hereditas 42, 799–809 (2020).

China National GeneBank Database (CNGBdb) https://db.cngb.org/search/experiment/CNX1147212/ (2024).

China National GeneBank Database (CNGBdb) https://db.cngb.org/search/experiment/CNX0988115/ (2024).

China National GeneBank Database (CNGBdb) https://db.cngb.org/search/experiment/CNX0988114/ (2024).

China National GeneBank Database (CNGBdb) https://db.cngb.org/search/experiment/CNX0988113/ (2024).

China National GeneBank Database (CNGBdb) https://db.cngb.org/search/experiment/CNX0987716/ (2024).

China National GeneBank Database (CNGBdb) https://db.cngb.org/search/experiment/CNX0987715/ (2024).

China National GeneBank Database (CNGBdb) https://db.cngb.org/search/assembly/CNA0138508/ (2024).

Liang, Z. L. Rosa hugonis isolate GXF17328-4, whole genome shotgun sequencing project. GenBank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc:JBJCIR000000000 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research program (Grant No. 2019QZKK05020107).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.X.F. and L.Z.L. conceived and designed the study. M.J., D.H.N., L.L.Y., L.S.Q., T.Z.Y., R.J. and J.R.F. prepared the materials and analyzed the data. L.Z.L. prepared the results and wrote the manuscript. G.X.F. edited and improved the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liang, Z., Miao, J., Deng, H. et al. A chromosomal-scale reference genome for Rosa hugonis. Sci Data 12, 272 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04526-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04526-7