Abstract

The data sets provide long-term information (2013–2022) of the presence-only of eight wild ungulates and red fox derived from harvest data in a grid of 5 × 5 km of Spain (21,836 cells). The collected data has been processed and reported yearly, as well as in two monitoring periods in accordance with Habitats Directive from the European Union to facilitate data reporting about the State of nature, and the sum of the whole period. Data sets are structured following the Darwin Core biological standard. The data set was published in the Spanish node of the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF), which are the most updated publicly available information for these species’ presence in Spain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Member States of the European Union (hereafter EU) have the duty of reporting the Conservation Status of Habitats and Species every six years since the approval of Habitats Directive 92/43/ECC and Bird Directive 2009/147/CE were approved. In Spain, there is not yet a national mammal monitoring program to assess the status (distribution and abundance) of species of no Community interest, nor to report the presence of species at coarse resolution.

Different data sources have been proposed to feed the sexennial reports. On the one hand, collaborative citizen science1,2 is a useful collaborative model for wildlife monitoring at large scales, particularly for taxa such as birds and butterflies3,4. Its application to mammals presents additional challenges due to their nocturnal behavior, lower detectability and the need for species-specific observation techniques. Therefore, opportunistic observations of mammals through citizen science are less frequent5. Nonetheless, citizen science initiatives employing camera-trapping are used to detect mammal species and to increase the number of opportunistic observations in areas where mammal sightings are limited6,7,8

On the other hand, another important source of data on species distribution and abundance is hunting yields of game species since: (i) they are yearly updated, as hunting is an activity taken every year9, (ii) they are spatially referenced9 and cover most countries’ territory, excluding some protected areas such as national parks and security areas around urban areas and roads10, and (iii) hunting managers may have the duty to report harvested animals to the administration (e.g. hunting managers in Spain are required to report this data to their respective Autonomous Communities, as outline in Decree 506/1971, of 25th March, which approves the Regulation for the execution of the Hunting Law of 4th April, 1970). In fact, hunting yields are often considered a proxy of abundance11,12 and they are frequently used in a wide variety of studies13,14,15,16. Therefore, hunting yields could be considered the most widespread information for reporting distribution and relative abundance of game species at national and European levels.

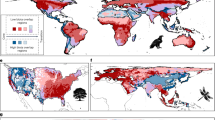

The National Wildlife Research Institute (IREC; CSIC-UCLM-JCCM) gathered and merged hunting yield data in Spain for wild ungulate and red fox for the period 2013–2022. The data set comprised hunting yields for 8 different ungulate species: barbary sheep (Ammotragus lervia), Southern chamois (Rupicapra pyrenaica), fallow deer (Dama dama), Iberian wild goat (Capra pyrenaica), European mouflon (Ovis aries), red deer (Cervus elaphus), roe deer (Capreolus capreolus), and wild boar (Sus scrofa) and a carnivore species: the red fox (Vulpes vulpes). The different administrative Autonomous Communities reported heterogeneous data sets, requiring data harmonization into a common structure9,17. The Autonomous Community is the primary political and administrative division below the national level, to which environmental policies, such as hunting and wildlife monitoring, are delegated. They may have varying priorities, resources and methodologies, which could potentially complicate national assessments on wildlife. A structured database following the Darwin Core standards was used18 for data harmonization purpose. However, there may be constraints on making public these data, which prevents raw data from being shared publicly at game management unit. They contain information of hunting yields, which is considered sensitive in some Autonomous Communities, such as the number, sex and age of hunted individuals, the number of individuals seen (alive) on a hunting day, the number of hunters, beaters and dogs, as well as the hunting method9. Hunting is an activity that constitutes an important economic resource in some Spanish regions and involves diverse stakeholders19,20,21,22. For this reason, we reached data-share agreements with each administrative Autonomous Communities, limiting the information that can be shared, maintaining the privacy of raw hunting yield data at the finest spatial scale (Fig. 1a). Nonetheless, if hunting yields are transformed at coarser spatial resolution and simplified to presence-only, the information could be made publicly available.

Consequently, a 5 × 5 km grid resolution was used for transferring hunting yield information into presence-only data. The transformed data sets include presence-only records for these wild species in Spain over the last decade. These valuable data are the most updated and complete known available distribution of the nine species in Spain, as the national-scale public information for mammals dates back to 200717. These data can be used in multiple studies concerning species management, spread of diseases, species distribution models13,14,23, etc. in the future.

Methods

We received the data after holding meetings with the game services of each Autonomous Community in Spain (i.e. 17 administrative regions). We reached a data-sharing agreement with each of them, which restricted the publication of data: raw data cannot be shared publicly at finest resolution provided; however, they can be transformed or aggregated into derived information products. The received data included hunting yields at hunting ground level from 2013/2014 to 2022/2023 hunting seasons (Figs. 1a and 2).

Since each Autonomous Community has its own (different) system/data set structure, we transformed and standardized the data received following the Wildlife Data Model template (WLDM24) developed by the ENETWILD consortium under EFSA18 (https://enetwild.com/), which follows the Darwin Core Criteria. Once we had harmonized a data set and joined with its spatial data (hunting ground perimeters), we validated the structure of each harmonized data source using ShinyIVT25. We use tidyverse 2.0.026 and sf 1.0-1627 packages of R 4.3.3 software28 for data management.

To update the distribution of presence of wild ungulates and red fox in Spain, it was decided to present the information in the 5 × 5 km squared grid of the European Environment Agency29 masked with Spain. Nonetheless, to facilitate comparisons with the latest publicly available information on mammals’ occurrence17, which has a grid resolution of 10 × 10 km, an additional field is included (verbatimCoordinates) to allow conversion from the 5 × 5 km grid to the 10 × 10 km grid.

After that, we transferred presence-only records of each species to the grid separately for each hunting season (Fig. 3), and for the total period. We considered that a species was presence for a hunting season only if at least one individual has been hunted in an overlapping hunting estate, by using the function gridPresence (Fig. 1b, see code section). Otherwise, the cell remained as unknown presence. It must be remarked that the later does not mean the species is absent in that cell, it just informs that it has not been hunted or reported, but no further inferences could be made about the absence of the species’ record.

An important consideration regarding data sets is that hunting yields are reported in relation to a hunting season which generally spans from September to March of the following year. Therefore, it is not feasible to assign a hunting yield to a specific natural year. The criteria for determining presence-only for each year was to take the first year that comprises the hunting season as presence since animals are mostly hunted between September and December30,31. For example, for the 2013/2014 hunting season presence-only would be referred to the year 2013.

In addition, we arranged the data in two monitoring time periods (2013–2018 and 2019–2022) which match reporting periods of the Habitat Directives from the EU. We grouped presence cell records and determined as “present” if in any year the species was present in that cell or “unknown presence” if it was not registered as present in any of the years that encompass each of the monitoring periods. We followed the same criterion for determining presence or unknown presence for the whole decade (2013–2022; Fig. 4).

Standardization

We formatted and published the data set, standardized to the Darwin Core structure32 (Fig. 1c), in the Spanish node of the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) through the Integrated Publishing Toolkit33 (IPT v3.0.4). Other countries could easily format and publish their data sets in GBIF following our procedure, as hunting yields from (almost) all European countries adhere to the same harmonization procedure13,14. Hunting yields are transformed into the WLDM template, joined with their hunting ground perimeters, and validated using ShinyIVT25. However, a significant challenge to consider is the varying spatial resolution at which each country reports their hunting yields, ranging from fine-scale resolutions (e.g., hunting grounds) to coarse-scale resolutions (e.g., NUTS2 level). Therefore, making our approach available may contribute to addressing the need of up-to-date information on species and habitat state not only at national but also at European level.

The main bottleneck in current biodiversity data flows is data integration and data accessibility. Only if different monitoring programs are harmonized, and particularly the spatial components of data merged, subsequent data streams will be possible to derive essential biodiversity variables34, such as those proposed by EuropaBON for a European Biodiversity Observation and Coordination (EBOCC). Our data sets, presented spatially in a grid, align with the requirements of the Habitat Directive and provide sufficient resolution to evaluate temporal changes, analyze spatial patterns, and investigate drivers of change. They are also available for inclusion in the derivation of the aforementioned biodiversity variables.

Data Records

The data set is available at GBIF35 as a Darwin Core Archive (DwC-A) under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0). The data sets presented here correspond to version 1.4, which is the most up-to-date compilation of presence-only records available for wild ungulates and red fox in Spain, derived from hunting yield data sets (Fig. 3).

Be aware that data sets do not contain complete information for all years, depending on the species and Autonomous Communities (Fig. 2). Despite the former, hunting yields from which data sets were derived from, are reported to public administrations on a mandatory and annual basis. Therefore, even if there are some current limitations in these data sets for certain species, hunting yields are continuously reviewed and updated, making them a valuable data source with extensive spatial and temporal coverage.

The current data set will be continuously updated as new data collections from providers are received and harmonized.

The DwC-A contains 1818198 records.

Remarks of the Darwin Core Archive available at GBIF are provided below:

-

basisOfRecord: (http://rs.tdwg.org/dwc/terms/basisOfRecord) Occurrence.

-

ocurrenceID: (http://rs.tdwg.org/dwc/terms/occurrenceID) unique ID code for each record.

-

occurrenceStatus: (http://rs.tdwg.org/dwc/terms/occurrenceStatus) it is reported as presence when at least one individual has been registered as hunted in that squared grid.

-

year: (http://rs.tdwg.org/dwc/terms/year) natural year that belongs to the year that the hunting season begins.

-

verbatimEventDate: (http://rs.tdwg.org/dwc/terms/verbatimEventDate) hunting season.

-

footprintWKT: (http://rs.tdwg.org/dwc/terms/footprintWKT) corresponds to the vertexes of the 5 × 5 km squared grid to which each record belongs.

-

decimalLongitude and decimalLatitude: correspond to the centroid coordinates of the 5 × 5 km squared grid (http://rs.tdwg.org/dwc/terms/decimalLongitude, http://rs.tdwg.org/dwc/terms/decimalLatitude).

-

coordinateUncertaintyInMeters: (http://rs.tdwg.org/dwc/terms/coordinateUncertaintyInMeters) it is recorded as 5 km, but that is the squared resolution, which corresponds to an error of 3535 meters.

-

geodeticDatum: (http://rs.tdwg.org/dwc/terms/coordinateUncertaintyInMeters) coordinate reference system that the coordinates are given using “WGS84”.

-

recordedBy: (http://rs.tdwg.org/dwc/iri/recordedBy) mainly performed by hunters, game managers and veterinary services.

-

identifiedBy: (http://rs.tdwg.org/dwc/iri/identifiedBy) administrative regional services that shared the information and cross-checked with veterinary and forestry services.

-

degreeOfEstablishment: (http://rs.tdwg.org/dwc/doc/doe/) degree to which an organism survives, reproduces, and expands its range at the given place and time.

-

establishmentMeans: (http://rs.tdwg.org/dwc/doc/em/) information about whether an organism or organisms have been introduced to a given place and time through the direct or indirect activity of modern humans.

-

verbatimCoordinateSystem: (http://rs.tdwg.org/dwc/doc/em/) the coordinate format for the verbatimCoordinates of each location.

-

verbatimcoordinates: (https://dwc.tdwg.org/list/#dwc_verbatimCoordinates) the verbatim original spatial coordinates of each location.

On the other hand, we generate a simulated count data set for three years in a GeoPackage file, which can be accessed on Zenodo36, as we cannot share the collected hunting yields due to data confidentiality agreements. We created random polygons in Spain and used a random Poisson distribution where the lambda parameter was set under a random normal distribution (mean = 50, sd = 10) to simulate count data for each of the years. Moreover, we selected a 25% of the polygons each year to change their count value to 0, to simulate unknown presences. The simulated count data is to demonstrate the transformation process from count data to presence-only data.

Technical Validation

Data sets are difficult to validate since the most updated information available dates to 200717. Nonetheless:

-

(a)

Data sets contain information of wild ungulate species and red fox. Public administrations collect this information mainly through different departments: agriculture and wildlife services, as well animal health departments, the later aimed at disease surveillance. The information sent to agriculture and environmental departments is normally collected by hunting managers, whereas the one sent to health departments is responsibility of veterinarians carrying out big game meat inspection in some regions. Therefore, the collected information can be double-checked. However, while this double-checking process is available for big game species, it is not feasible for small game species. Nevertheless, holding different hunts on different days and the multiple participation of hunters mitigates the risk of errors in species identification.

-

(b)

Reporting hunting yields to public administrations is mandatory in Spain. Hunting estates that violate the law by not sending their annual activity reports may face penalties, such as hunting bans in subsequent season/s. However, these sanctions are not always applied, leading to potential data gaps for certain years and hunting grounds.

-

(c)

Hunting or population control for conflict management (e.g., to prevent damage to crops, even in areas that administratively are not considered hunting estates, national parks, peri-urban) may not always be reported or included to hunting yield databases in some Autonomous Communities. This may result in gaps in data, especially in areas where regular hunting activities are not allowed (e.g., some blank cells in our maps, such as for wild boar).

-

(d)

Data set with full hunting yields by region (RAW data) was harmonized and checked before being transformed into a presence-only grid. Data harmonization was performed by the same team which followed the same manual procedure to ensure consistency. After data was harmonized, the team monitored the quality of the data product: i) ensuring no missing values by summing the total number of individuals hunted per species and hunting season and comparing the result to the RAW data total, ii) avoiding overcounting by identifying duplicate hunting yields per species and hunting season, and iii) verifying that counts correspond to their respective hunting grounds by randomly selecting 30 rows per along the terciles of harmonized data set and cross-checking the hunting ground and counts with the RAW data. Data validation was made under the Integrated Validation Tool (IVT25) developed by ENETWILD.

-

(e)

In addition, a simulated data set is provided as well as the code used to generate presence-only data, which ensures reproducibility of the whole process.

Usage Notes

Monitoring programs developed for mammal species of Community interest are, mainly, those for which conservation status was reserved and are carried out at small-scale37,38,39,40,41. On the contrary, widespread, and abundant mammals, which in their majority are considered game species, have lacked monitoring programs to assess either their presence or abundance42. There are only few proposals for monitoring those species that have started to cause economic damages to agriculture, livestock or through car crashes43,44,45,46. Therefore, hunting yields have become the most commonly used source of information for knowing their distribution and abundance at national or European scale. The data set provided, which update the presence-only of several game species per year, could inform about changes in their distribution range. They can be used also to evaluate environmental-species relationships by modelling or provide important information to data-integration models23. Moreover, the methodology proposed here could be extended to other game species, as lagomorphs, bird game and fishing species.

The presence-only records provided in the data set (Fig. 3), correspond to all data received (Fig. 2). Not all Autonomous Communities reported the same hunting seasons and/or species, as that also depends on species distribution. For example, Southern chamois is only distributed on Cantabrian and Pyrenean mountain range, but not in Southern Spain; contrarily, European mouflon is distributed in the mid-term Southern Spain, but not in the Northern. Future updates will incorporate new data obtained from providers. European and Spanish authorities are increasingly involved into the development of wildlife monitoring programs47. In accordance, there are funding projects with that aim at European (ENETWILD and EOW project) and National scale (HAWIPO, AGROBOAR, FAUNET). These projects are going to give the opportunity of maintaining an updated presence-only data set for these game species. For that reason, we encourage readers to look for updated versions on the GBIF repository after this publication.

The function developed for transforming the data (gridPresence, see code availability) could also be used for other types of counting data transformation into presence-only data.

Code availability

Due to data confidentiality agreements, collected hunting yields cannot be shared. However, a simulated count dataset for several years is provided in a GeoPackage file, along with the masked 5 × 5 km grid from the EEA, to show the transformation process from count data set to presence-only data.

We make the simulated count data set by generating random polygons within the surface of Spain (lines 31–46). For each random polygon, we generated three count surveys data sets (e.g. year) based on a random Poisson distribution, where the lambda parameter followed a random normal distribution (mean = 50, sd = 10; lines 31–46). To simulate unknown presences, 25% of the polygons in each survey were randomly assigned a count of 0 (lines 60–62). We exported the information as a vectorial layer in a Geopackage (lines 82–89). The simulated count data set represents the simplest data structure that researchers may encounter in their RAW or harmonized data sets. The R script example file is prepared for transforming three years counts to 5 × 5 km grid (line 24), as well as 10 x 10 km grid. The transformation of the 5 × 5 km grid to the 10 x 10 km grid can be found at line 28. The function used for transforming hunting yields data to presence-only (gridPresence) is also provided (lines 46–93). An example of how to run the function for more than a year and for both grid resolutions is given as well (lines 97–105). Both results are given and plotted (lines 109–128). The R script files has been written in R 4.3.3 computing language and utilized the packages tidyverse 2.0.026, sf 1.0-1627, terra 1.8-1548, dismo 1.3-1649, and deldir 2.0–450.

We released version 1.6.0 of the transformation process (code and data set files) in Zenodo36. There are also available at: https://github.com/robinilla/gridPresence.

References

Shirk, J. L. et al. Public participation in scientific research: A framework for deliberate design. Ecology and Society 17 (2012).

Fraisl, D. et al. Citizen science in environmental and ecological sciences. Nature Reviews Methods Primers 2 (2022).

Sullivan, B. L. et al. eBird: A citizen-based bird observation network in the biological sciences. Biol Conserv 142, 2282–2292 (2009).

Van Swaay, C. A. M., Nowicki, P., Settele, J. & Van Strien, A. J. Butterfly monitoring in Europe: Methods, applications and perspectives. Biodivers Conserv 17, 3455–3469 (2008).

Battersby, J. E. & Greenwood, J. J. D. Monitoring terrestrial mammals in the UK: Past, present, and future, using lessons from the bird world. Mamm Rev 34, 3–29 (2004).

Casaer, J., Milotic, T., Liefting, Y., Desmet, P. & Jansen, P. Agouti: A platform for processing and archiving of camera trap images. Biodiversity Information Science and Standards 3 (2019).

Hsing, P. Y. et al. Large-scale mammal monitoring: The potential of a citizen science camera-trapping project in the United Kingdom. Ecological Solutions and Evidence 3 (2022).

Lasky, M. et al. Candid critters: Challenges and solutions in a large-scale citizen science camera trap project. Citiz Sci 6 (2021).

Ruiz-Rodríguez, C. et al. Towards standardising the collection of game statistics in Europe: a case study. Eur J Wildl Res 69 (2023).

Carpio, A. J. et al. The prohibition of recreational hunting of wild ungulates in Spanish National Parks: Challenges and opportunities. Science of The Total Environment 171363, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.171363 (2024).

Imperio, S., Ferrante, M., Grignetti, A., Santini, G. & Focardi, S. Investigating population dynamics in ungulates: Do hunting statistics make up a good index of population abundance? Wildlife Biol 16, 205–214 (2010).

Fernández-López, J. et al. Game target-group: Implementing inhomogeneous Poisson point process to estimate animal abundance from harvest data. Methods Ecol Evol https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.14458 (2024).

ENETWILD-consortium et al. Wild carnivore occurrence and models of hunting yield abundance at European scale: first models for red fox and badger. EFSA Supporting Publications 20 (2023).

ENETWILD consortium et al. New models for wild ungulates occurrence and hunting yield abundance at European scale. EFSA Supporting Publications 19 (2022).

Baz-Flores, S. et al. Mapping the risk of exposure to Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever virus in the Iberian Peninsula using Eurasian wild boar (Sus scrofa) as a model. Ticks Tick Borne Dis 15 (2024).

Delibes-Mateos, M., Farfán, M. Á., Olivero, J., Márquez, A. L. & Vargas, J. M. Long-term changes in game species over a long period of transformation in the Iberian Mediterranean landscape. Environ Manage 43, 1256–1268 (2009).

Palomo, L. J., Gisbert, J. & Blanco, J. C. Atlas y Libro Rojo de Los Mamíferos Terrestres de España. (Dirección General para la Biodiversidad-SECEM-SECEM, Madrid, 2007).

ENETWILD consortium. et al. Applying the Darwin core standard to the monitoring of wildlife species, their management and estimated records. EFSA Supporting Publications 17(4), 1841E (2020).

Kupren, K. & Hakuc-Błazowska, A. Profile of a Modern Hunter and the Socio-Economic Significance of Hunting in Poland as Compared to European Data. Land (Basel) 10, 1178 (2021).

Sánchez-García, C. et al. Evaluation of the economics of sport hunting in Spain through regional surveys. International Journal of Environmental Studies 78, 517–531 (2021).

Middleton, A. The Economics of Hunting in Europe. FACE Final Report. MEP https://face.eu/sites/default/files/attachments/framework_for_assessing_the_economics_of_hunting_final_.en_.pdf (2014).

Martínez-Jauregui, M. et al. Hunting in European mountain systems: an economic assessment of game gross margins in nine case study areas. Eur J Wildl Res 60, 933–936 (2014).

Fernández-López, J., Acevedo, P. & Gimenez, O. La unión hace la fuerza: modelos de distribución de especies integrando diferentes fuentes de datos. Ecosistemas 32 (2023).

Body, G. et al. Implementation of the wildlife monitoring standard on excel. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.3735781 (2020).

ENETWILD-consortium et al. The ENETWILD data exploration tool (ENETWILD-DET): a web app to visualize and download wildlife population data (5.1). Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8214252 (2023).

Wickham, H. et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J Open Source Softw 4, 1686 (2019).

Pebesma, E. Simple Features for R: Standardized Support for Spatial Vector Data. R J 10, 439–446 (2018).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria (2022).

European Environment Agency. EEA Reference grid for Europe. https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/datahub/datahubitem-view/3c362237-daa4-45e2-8c16-aaadfb1a003b (2024).

Milner, J. M. et al. Temporal and spatial development of red deer harvesting in Europe: Biological and cultural factors. Journal of Applied Ecology 43, 721–734 (2006).

Datta-Roy, A. Spatial and Temporal Patterns of Large Mammal Hunting in a Changing Swidden System of Arunachal Pradesh, India. Hum Ecol 50, 697–710 (2022).

Wieczorek, J. et al. Darwin Core: An evolving community-developed biodiversity data standard. PLoS One 7 (2012).

Robertson, T. et al. The GBIF integrated publishing toolkit: Facilitating the efficient publishing of biodiversity data on the internet. PLoS One 9 (2014).

Liquete, C. et al. EuropaBON D2.3 Proposal for an EU Biodiversity Observation Coordination Centre (EBOCC). https://europabon.org (2024).

Illanas S. et al. Data set: Only-presence data for wild ungulates and red fox in Spain based on hunting yields. https://doi.org/10.15470/lve3wn (2024).

Illanas, S. gridPresence: v1.6.0. Simulated data set and function: Presence-only data for wild ungulates and red fox in Spain based on hunting yields. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14767197 (2025).

Rodríguez, A. & Calzada, J. Lynx pardinus. The IUCN Red List of Threathened Species http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/12520/0 (2015).

Blanco, J. C., Ballesteros, F., Palomero, G. & Lopez-Bao, J. V. Not exodus, but population increase and gene flow restoration in Cantabrian brown bear (Ursus arctos) subpopulations. Comment on Gregório et al. 2020. PLoS One 15(11), e0240698 (2020).

Palazón, S. Results of the Fourth Eurasian Otter (Lutra Lutra) Survey in Spain. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull vol. 40 (2023).

Croose, E. et al. Mink on the brink: comparing survey methods for detecting a critically endangered carnivore, the European mink Mustela lutreola. Eur J Wildl Res 69 (2023).

Gisbert, J. & García-Perea, R. History of the decline of the Iberian desman Galemys pyrenaicus (É. Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, 1811) in the Central System (Iberian Peninsula). Munibe. Monographs Nature Series 3, 19–35 (2014).

ENETWILD-consortium et al. A guidance on how to start up a national wildlife population monitoring program harmonizable at European level. EFSA Supporting Publications 20 (2023).

European Climate, I. and E. E. A. The Easter Bunny, farmers and hunters: how LIFE brings all sides together - European Commission. European Climate, Infrastructure and Environment Executive Agency https://cinea.ec.europa.eu/news-events/news/easter-bunny-farmers-and-hunters-how-life-brings-all-sides-together-2024-03-27_en (2024).

Fernández-López, J., Blanco-Aguiar, J. A., Vicente, J. & Acevedo, P. Can we model distribution of population abundance from wildlife–vehicles collision data? Ecography 2022 (2022).

Schwartz, A. L. W., Shilling, F. M. & Perkins, S. E. The value of monitoring wildlife roadkill. Eur J Wildl Res 66, 18 (2020).

SECEM. Proyecto SAFE - Stop Atropellos de Fauna en España. https://secem.es/estudios/programas/proyecto-safe (2021).

Guerrasio, T. et al. Wild ungulate density data generated by camera trapping in 37 European areas: first output of the European Observatory of Wildlife (EOW). EFSA Supporting Publications 20 (2023).

Hijmans, R. J. terra: Spatial Data Analysis. R package version 1.8-15 https://doi.org/10.32614/CRAN.package.terra (2025).

Hijmans, R., Phillips, S., Leathwick, J. & Elith, J. dismo: Species Distribution Modeling. R package version 1.3-16 https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/dismo/index.html, https://doi.org/10.32614/CRAN.package.dismo (2024).

Turner, R. deldir: Delaunay Triangulation and Dirichlet (Voronoi) Tessellation. R package version 2.0-4 https://doi.org/10.32614/CRAN.package.deldir (2024).

Acknowledgements

The investment of time for making the data set available was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation thanks to the 2020 PhD contract (PRE2020-095091) associated to I + D + i HAWIPO Project (PID2019-111699RB-I00), the I + D + I AGROBOAR Project (PID2022-142919OB-100), funded by MCIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033/y – FEDER – EU. The Spanish Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food thanks to the FAUNET Management Order (https://www.boe.es/diario_boe/txt.php?id=BOE-A-2023-17249) and the support of the Subdirectorate General for Livestock and Hunting Productions. The Margarita Salas from the European Union – NextGenerationEU through the Complutense University of Madrid. Talent Return and Retention Project SBPLY/23/180225/000176 – and researcher contract for scientific excellence from the UCLM co-financed by the European Social Fund Plus. All data providers: Diputación Foral de Álava, Diputación Foral de Bizkaia, Diputación Foral de Gipuzkoa, Generalitat de Cataluña, Generalitat Valenciana, Gobierno de Aragón, Gobierno de Cantabria, Gobierno de la Comunidad de Madrid, Gobierno de la Región de Murcia, Gobierno de La Rioja, Gobierno del Principado de Asturias, Gobierno de Navarra, Junta de Andalucía, Junta de Castilla y León, Junta de Comunidades de Castilla-La Mancha, Junta de Extremadura, Junta de Galicia. Katia Cezón and Francisco Pando kindly provided support to incorporate IREC into GBIF as data provider and helped to properly format the database to meet GBIF requirements.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.I.: contacted data providers, collected, stored, harmonized, and transformed data information, uploaded information to the GBIF repository, wrote the article and prepared the figures. J.A.B.-A.: contacted data providers, collected and stored data information. Helped with Darwin Core transformation and uploaded it to the GBIF repository. C.R.-R.: contacted data providers, collected, stored and harmonized data information. S.L.-P.: harmonized and validated data information. A.G.-M.: contacted data providers, collected, stored, harmonized and validated data information. Made the data share agreement with data providers. L.P., M.S.-P.: harmonized and validated data information. J.F.-L.: had the idea of the data paper and helped to draft the manuscript. P.A.: acquired financial support and helped to draft the manuscript. J.V.: acquired financial support and helped to draft the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Illanas, S., Fernández-López, J., Vicente, J. et al. Presence-only data for wild ungulates and red fox in Spain based on hunting yields over a 10-year period. Sci Data 12, 236 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04574-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04574-z