Abstract

Industrial lands, as a key component of economic development, pose great environmental challenges, which underscores the need for close global monitoring to support sustainable urban development. Despite this importance, global city-level maps of industrial land use, especially over multiple years, have been lacking. Here, we present a 10-m resolution global dataset tracking industrial land use in 1,093 large cities (area 100 km² or more) from 2017 to 2023. Using multisource geospatial data and machine learning, the dataset achieves a high overall accuracy of 91.87% to 92.21% across the seven-year period, aligning well with official city maps. We further validated its reliability by computing industrial land area per capita for 1,093 cities, which correlated strongly with per capita CO2 emissions (r = 0.72). These maps offer a valuable tool for tracking industrial land use changes and assessing their impact on urban ecosystems. The dataset is a critical resource for studying the links between industrialization, urbanization, and environmental sustainability while providing insights to policymakers on balancing economic and environmental priorities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Industrial lands serve as a hub for manufacturing, logistics, and other industrial activities that drive economic growth1,2, and often are a key component in urban landscape. The associated sectors generate job opportunities and foster innovations, significantly contributing to urban economies3,4,5. However, industrial lands face numerous environmental challenges, since industrial activities are major sources of carbon emissions and pollutants that contribute to climate change, degrade air and water quality, and emit significant amounts of heat6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13. Consequently, balancing economic and environmental benefits, as well as societal impacts, has become a critical issue in urban planning, land management, and sustainable urban development. Monitoring industrial land areas to assess changes and understanding their dynamics across cities is a compelling issue, supporting sustainable industrial development and urban planning efforts14,15,16.

The availability of satellite imagery, as well as the advancement of computation power through cloud platforms, offers a new opportunity for developing large-scale global land data products17,18,19,20. Despite this, industrial land use maps at the global city level are significantly lacking. While some studies have mapped industrial land areas, those efforts are typically limited to local scales15,21,22,23,24,25,26. Cities, like Los Angeles, Melbourne, and Singapore, produce official industrial land maps through government initiatives (see Supplementary Table 1), but they are confined to their regions, and are not useful for understanding sustainable industrial land development across different stages and geographical areas. Although datasets on impervious surfaces27,28, human settlements18, and residential land areas29 can support global urban sustainability studies, they do not provide information on industrial land areas. Consequently, comprehensive industrial land maps at the global city level are urgently needed to monitor sustainable industrial development.

This study addresses the gap by producing industrial land area maps for 1,093 global large cities at a 10 m spatial resolution, from 2017 to 2023. We used diverse satellite-based data, including multispectral reflectance and nighttime light data, to identify the surface characteristics and activities associated with industrial lands. We further used OpenStreetMap (OSM) land use data and various built-up surface datasets to derive training samples for distinguishing between industrial and non-industrial land. Random forest machine-learning algorithms were employed for the modeling process. Quantitative evaluation of the resulting maps, using separate validation samples, achieved an overall accuracy (OA) of 92.07% and a mean F1 score of 91.48% for industrial land across the seven years. Qualitative comparisons were made with official industrial land area data from various cities.

Furthermore, we validated the dataset by computing industrial land area per capita for all 1,093 cities, revealing a strong correlation with per capita fossil fuel CO2 emissions (r = 0.72). Our maps will benefit stakeholders by aiding policymakers in designing effective, environmentally sustainable industrial strategies while providing urban planners and environmental scientists with crucial insights for infrastructure development and assessing the impact of industrial activities on urban ecosystems.

Methods

Selection of 1,093 Cities

To select cities for industrial land mapping and delineate their boundaries, we adapted the Global Human Settlement Layer Urban Centres Database (GHS-UCDB) R2019A30. From the 13,135 cities listed in the GHS-UCDB, we selected those with an area larger than 100 km², a widely applied criterion for identifying large cities in global urban studies31,32. Consequently, 1,093 cities were selected for mapping; their distribution is illustrated in Fig. 1. These cities are globally distributed, with 531 in Asia, followed by Europe (174), North America (165), South America (113), Africa (99), and Oceania (11). We created standardized rectangular boundaries for 1,093 cities based on the original boundaries provided by the GHS-UCDB. To offer flexibility for map users, we applied a 1.5 km buffer to these rectangular boundaries, defining the final target areas for industrial land mapping in each city.

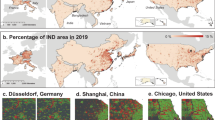

Distribution of the 1,093 cities mapped for their industrial lands. The background map depicts urban ecoregions33. The pie chart in the bottom left shows the number of cities analyzed in each continent, highlighting their distribution across geographic regions.

Reference data sampling and city clustering

The process of producing 10 m industrial land maps involves two key steps: 1) designing the reference sampling sets and clustering the 1,093 cities for modeling; and 2) modeling and mapping industrial lands (Fig. 2). The construction of reference sampling sets in the first step is crucial for both model training and validation. This study defines “industrial lands” as areas specifically built-up and designated for industrial activities such as manufacturing, production, storage, or distribution. To establish reliable reference samples for model training and validation, we used multiple sources, including OSM (https://download.geofabrik.de), 10 m ESRI land cover data produced by Impact Observatory (https://www.impactobservatory.com/10m-land-cover), and World Settlement Footprint (WSF) 3D datasets (https://geoservice.dlr.de/web/datasets/wsf_3d).

Flow chart illustrating the industrial land mapping and modeling process in this study. The workflow is divided into two main steps: (1) reference data sampling and clustering of 1,093 cities for modeling, and (2) modeling and mapping of industrial land. The second process can be applied separately for each year for each cluster.

First, we used OSM data to identify areas of industrial and non-industrial land use. Specifically, we downloaded shapefiles tagged with “land use” from Geofabrik for all 1,093 cities (https://overpass-api.de/). The “industrial land” category in OSM includes buildings such as workshops, factories, warehouses, and associated infrastructure (e.g., car parks, service roads, yards). These OSM features were reclassified into two classes: industrial land use and non-industrial land use according to the above definition. Subsequently, we split the classified features into training and validation sets in an 80 to 20 ratio for each city.

Next, to ensure the reliability of the reference samples, we delineated “built-up” areas from the 10 m annual ESRI land cover data, focusing on regions consistently classified as built-up from 2017 to 2023. To enhance the diversity and robustness of the reference points, these built-up layers were overlaid with the WSF 3D volume layer (greater than 0), which facilitated the extraction of built-up areas with varied settlement volumes. We then converted the combined layers within the OSM land use features into point data representing industrial and non-industrial land areas. To minimize redundancy, we retained only one point per cluster of adjacent pixels with identical built-up volumes.

Considering the trade-off between computational cost and performance, we selected a threshold of 5,000 industrial land training samples for modeling. Among the 1,093 cities, 29 exceeded this threshold (see Fig. 1 for the distribution and Supplementary Table 1 for the full list), and these cities were modeled individually. For the remaining 1,064 cities with fewer reference samples, we adopted a strategy of grouping multiple cities to facilitate industrial land mapping.

To achieve this, we used urban ecoregions as the basis for grouping cities33. Urban ecoregions are a global classification system defined by urban topology, per-capita income, geographic region, and climate characteristics, resulting in 16 quasi-homogeneous strata (Fig. 1). This framework was selected based on its potential to effectively group cities with similar industrial land characteristics, as it accounts for structural composition, economic activity, and environmental conditions34.

Most cities in our study were classified into Urban Ecoregions 1–14 (see Fig. 1). A few cities fell within Urban Ecoregions 15 and 16, which lacked sufficient representation. These cities were reassigned to the nearest suitable urban ecoregion. As a result, we modeled 29 cities individually and grouped the remaining cities into 14 urban ecoregion clusters, creating a total of the 43 clusters for the modeling process.

Modeling and mapping of industrial lands

We constructed separate models for each of the 43 clusters. For each cluster, we extracted 5,000 industrial land samples and 30,000 non-industrial land samples from the candidate training sets. This ratio was set based on computational limits and insights from previous studies16. Among the non-industrial samples, we aimed for 25,000 residential land samples and 5,000 samples from other uses, such as commercial areas and open spaces.

The models, spanning the years 2017 to 2023, were developed annually using the Google Earth Engine (GEE) platform (https://earthengine.google.com). We used a total of 37 input variables, as detailed in Table 1. Initially, ten bands from Sentinel-2A reflectance data (https://scihub.copernicus.eu) were processed, including blue, green, red, red edge (1–4), Near-Infrared (NIR), and Short-Wave Infrared (SWIR) 1–2 bands. We selected only imagery with less than 30% cloud cover, covering city boundaries within each cluster. We used the Cloud Score + quality assessment process to exclude clouds35, and we computed the median reflectance value for each band.

Due to the clustered characteristics of industrial land areas, we also extracted neighboring textures from the four reflectance bands (blue, green, red, and NIR). These bands, with a resolution of 10 m, were used to derive five texture metrics from the Gray Level Co-occurrence Matrix: Contrast, Homogeneity, Entropy, Angular Second Moment, and Dissimilarity23. We tested neighborhood sizes from 10 to 50, in increments of 10, to find the optimal dimensions for each of the 43 clusters. Nighttime light data, capturing the unique emission patterns of industrial areas36, were integrated by calculating the yearly medians from the monthly average nighttime radiance images provided the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) (https://eogdata.mines.edu/products/vnl/#monthly).

We also included products indicative of industrial land characteristics, such as non-residential built-up area and volume37,38, and global power system data39 (considering the large electricity usage in industrial areas). Lastly, we added three geographic factors: gridded latitude, longitude, and the Forest and Buildings Removed Digital Elevation Model (FABDEM)40. These geographic variables capture different topographic features across multiple cities within a cluster. All input variables were resampled to a 10 m resolution, matching the target resolution for industrial land mapping.

For the modeling process, we employed a random forest machine learning model on the GEE platform. Random forest is favored for global-scale urban product mapping through GEE due to its robustness, ability to process large datasets with relatively few parameters, and high accuracy23,41,42. Additionally, random forest has built-in mechanisms to handle multicollinearity, reduce overfitting risks through bootstrapping, and provide feature importance rankings, making it an ideal choice for this study43,44,45.

In our model, we set the number of trees to 500, while keeping the other parameters at their default settings, which are widely used in environmental product modeling42,46,47. We used the 37 input variables to train the model, with the selected reference samples as the target variable for binary classification (industrial land and non-industrial land). The trained model for each cluster was applied to the built-up areas derived from 10 m ESRI land cover data from 2017 to 2023, resulting in industrial land maps at a 10 m resolution for 1,093 cities.

To enhance the accuracy of the final maps, we applied both spatial and temporal filtering to reduce classification noise. First, a 3 × 3 Gaussian filter was applied as a spatial smoothing step to minimize small-scale misclassifications. Subsequently, a majority-mode filter was employed as a temporal smoothing technique, ensuring consistency across the seven years of generated maps41,48,49.

Evaluation of the industrial land map

We assessed the accuracy of the generated industrial land map using validation samples. From the candidate validation sample sets, 500 samples of industrial land and 500 samples of non-industrial land were randomly extracted for each cluster. To avoid spatial autocorrelation, validation samples were located at least 1 km away from the training samples. These samples facilitated the construction of a confusion matrix for each cluster, from which we derived key accuracy metrics: OA (Eq. (1)), F1 score (Eq. (2)), and Cohen’s Kappa (kappa) (Eq. (3)).

Where TP, TN, FP, and FN denote the number of pixels classified as true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives, respectively.

To further validate our mapping approach, we conducted a comparative analysis with official industrial land zone data from six representative cities—Ulsan, South Korea (https://egis.me.go.kr), Nagoya, Japan (https://nlftp.mlit.go.jp), Singapore (https://www.ura.gov.sg), Los Angeles, United States (https://geohub.lacity.org), Melbourne, Australia (https://datashare.maps.vic.gov.au), and Nairobi, Kenya (https://datacatalog.worldbank.org). These cities are among the major industrial hubs in their respective countries, and also provide information on industrial land areas as open-source data. Details of these official data are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. Additionally, we compared our industrial land area with the area designated as Heavy Industry (Local Climate Zone 10, LCZ10) in the local climate zone classification41, facilitating a discussion on the distribution and variety of industrial land types within the cities.

As part of our evaluation of industrial land maps, we used CO2 emissions from fossil fuel combustion as a key environmental indicator, given that industrial activity is a major contributor to these emissions16,50. Specifically, we validated industrial land use relative to population (measured as industrial land area per capita) by examining its correlation with per capita CO2 emissions from fossil fuel combustion across 1,093 cities in 2020, the mid-year of the study period. For this validation, we used population data from WorldPop (https://www.worldpop.org) and CO2 emissions data from the Open-Data Inventory for Anthropogenic Carbon Dioxide51.

Data Records

The 10 m resolution industrial land maps for 1,093 global cities from 2017 to 2023 are freely available in Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14832219)52.

Each year’s map is accessible as a separate ZIP file, such as Industrial_land_10m_1093cities_2017.zip for 2017. Each ZIP file contains the industrial land maps for all 1,093 cities in TIF format. The file naming convention Industrial_land_XXX_YYY_YEAR.tif indicates the country code (XXX), city ID (YYY), and year (YEAR).

City IDs are detailed in The Excel file 1093_city_information.xlsx, specifically the ID_HDC_G0 column, details the city IDs. For example, Industrial_land_USA_634_2017.tif denotes the industrial land map for Chicago, United States, in 2017. Each TIF file has a 10 m spatial resolution with the GCS_WGS_1984 spatial projection. The maps include three classes:

-

Class 1: Industrial land in built-up areas

-

Class 2: Non-industrial land in built-up areas

-

Class 0: Non-built-up areas

A detailed summary of city-specific information, including the annual total industrial land area, is provided in 1093_city_information.xlsx. This file includes:

-

ID_HDC_G0: Unique city ID (Urban Centre)

-

CTR_MN_NM: Main country name

-

CTR_MN_ISO: ISO-3 country codes

-

UC_NM_MN: Main city (Urban Centre) name

-

UC_NM_LST: Full list of assigned city (Urban Centre) names

-

URB_ECOREGION: Assigned urban ecoregion

-

CLUSTER: Assigned cluster number in industrial land modeling

-

IND_YEAR: Total industrial land area for each year (in m2).

We also provide the Validation Package (Validation_Package.zip), which includes datasets for assessing the accuracy of industrial land mapping.

Technical Validation

Model accuracy assessment

The accuracy assessment of the industrial land maps, validated using an independent sample, appears in Fig. 3. The results from forty-three clusters were combined in a confusion matrix, weighted according to their total impervious surface area. The OA across the seven years averages at 92.07%. The year with the highest accuracy is 2019 (OA: 92.21%), while 2017 shows the lowest accuracy (OA: 91.87%). The year-to-year accuracy, however, remains remarkably stable, demonstrating the robustness of the model (standard deviation: 0.1%).

Confusion matrices for industrial land classification, 2017–2023. Each matrix shows the true positive rate (correctly classified industrial land), false positive rate (non-industrial land incorrectly classified as industrial), false negative rate (industrial land incorrectly classified as non-industrial), and true negative rate (correctly classified non-industrial land). The overall accuracy (OA) for each year is shown above the matrices, highlighting the consistent performance and robustness of the classification model across years. Each matrix aggregates results from 43 clusters, weighted by the built-up area of the cities within each cluster. Validation sample sizes for both industrial and non-industrial land are 500 per cluster, per year.

Across all years, the classification model demonstrates consistent performance with similar percentages for true positives (industrial land) and true negatives (non-industrial land). The true positive rate for industrial land fluctuates slightly; the highest is 43.54% in 2019, and the lowest is 43.28% in 2017. The false positive rate for industrial land proves relatively stable, ranging from 6.46% in 2019 to 6.72% in 2017. The false negative rate for non-industrial land remains around 1.34%–1.43%, while the true negative rate for non-industrial land consistently hovers around 48.57%–48.66%. Overall, the model maintains a good true positive rate for industrial land and demonstrates a strong ability to correctly classify non-industrial land, as evidenced by the high true negative rate.

We applied spatial and temporal filtering to the industrial land maps, which were generated using the random forest model. A comparison of map accuracy with and without this filtering technique (see Supplementary Figure 1) demonstrated a consistent improvement in OA across all seven years. Although the increase in accuracy was not substantial, this method helped reduce noises, producing more accurate maps41.

Figure 4 presents a performance analysis of the industrial land classification model, illustrating the seven-year average of OA, F1 score for industrial land, and kappa metrics across fourteen urban ecoregions. The OA ranges from approximately 87% to nearly 95%, indicating a high level of accuracy in classifying both industrial and non-industrial land across different urban ecoregions. Notably, nine ecoregions exhibit an OA above 90%, which further verifies the map’s robustness and reliability. The F1 score for industrial land fluctuates between 86% and 95% across the ecoregions. The kappa statistic ranges from 0.75 to 0.91, with nine ecoregions showing kappa values above 0.8, suggesting strong agreement and, again, reinforcing the model’s effectiveness.

Performance analysis of the industrial land classification model across fourteen urban ecoregions over the study period. The bars represent (left) overall accuracy (OA), (middle) F1 score for industrial land in percentage, and (right) kappa statistic for each of the fourteen urban ecoregions. The accuracy of the 29 individually modeled cities was weighted by their built-up surface area and aggregated according to the urban ecoregion to which each city belongs. The detailed accuracy metrics for all 29 cities are provided in Supplementary Figure 3.

Among the fourteen urban ecoregions, regions 8, 3 and 10 demonstrate high accuracy, each with an OA over 95% and F1 scores also exceeding 95%. Most cities in these regions are in Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa (see Fig. 1 for distribution). In contrast, regions 11, 1, 9 and 2 show lower accuracy, with OA below 90% and F1 scores under 89%. These regions primarily encompass cities in Europe, North America, and South America. One potential explanation for this discrepancy is the relatively lower producer’s accuracy observed in these regions (see Supplementary Figure 2). Specifically, industrial land in these areas may be misclassified as non-industrial land due to higher feature similarity with other land-use types, such as commercial lands (see Supplementary Figures 4, 5 for an example).

This regional variation reflects a broader trend observed across all urban ecoregions, where user’s accuracy (average 97%) consistently exceeds producer’s accuracy (average 86%) for industrial land classification (see Supplementary Figure 2). The high user’s accuracy indicates the reliability of classified industrial land areas, aiding users in accurately identifying industrial zones within the dataset.

Qualitative assessment of industrial land mapping

Figure 5 presents a map of representative cities with substantial industrial land areas across fourteen urban ecoregions. The map shows the distribution of industrial lands over built-up surfaces, allowing clear identification of their patterns. For example, Guangzhou and Moscow exhibit relatively scattered industrial areas throughout the city. In contrast, industrial lands in Shanghai and Ürümqi are primarily concentrated in peri-urban areas rather than the urban core. Cities like Los Angeles, Phoenix, and Johannesburg prominently feature large to medium-sized industrial zones clustered in specific areas, such as industrial corridors.

Spatial distribution of industrial and non-industrial land areas in selected global cities. The figure highlights fourteen cities selected for their extensive industrial land areas, representing each urban ecoregion. The map uses data from 2023, the latest in our dataset. Black areas indicate non-built-up surfaces, and sky-blue areas represent water regions.

With a high spatial resolution of 10 m, our map allows for precise distinction between industrial and non-industrial land boundaries. Figure 6 shows several renowned industrial park areas overlaid with our produced industrial land map. Their zoning areas are delineated and identifiable amidst surrounding non-industrial lands. This indicates that our data can be used as a base map for analyzing industrial land zones, including those examining the environmental impacts of industrial parks (for example, industrial heat island) or eco-industrial park development.

Maps of notable industrial zones highlighting industrial lands (transparent red) against non-industrial surroundings (transparent green). The map represents data from the year 2023, the most recent in our dataset. The maps also overlay point-based datasets, including the Global Power Plant Database53 (yellow dots) and the Global Database of Iron and Steel Production Assets54 (blue dots). Background satellite images were sourced from Bing © Microsoft Maps on ArcGIS.

Furthermore, our industrial land map is complementary to other global datasets, such as the Global Power Plant Database53 and the Global Database of Iron and Steel Production Assets54. These datasets provide point-based information on the locations of facilities, as illustrated in Fig. 6. Notably, the locations of these facilities within the six representative industrial zones are accurately classified as industrial land in our dataset. This alignment demonstrates that our map not only captures the precise location of industrial facilities but also offers a more comprehensive depiction of the spatial distribution of industrial zones surrounding these key assets. While existing point-based datasets provide valuable information on emission sources7,55, they often lack the spatial granularity required to map the detailed distribution of industrial facilities within a given region. Our industrial land maps can be synergistically used with these datasets to identify emission hotspots and delineate the spatial distribution of industrial activities more precisely.

We compared the industrial land map with publicly available official data for six cities (Fig. 7). Despite differences in data formats among official maps (all vector zoning formats except Ulsan; see Supplementary Table 1) and subtle differences in industrial land definitions, the overall distribution of industrial areas aligned well with our map. When comparing the industrial land area ratio over a 5 × 5 km grid between our map and the official data (Fig. 8), we observe a high correlation (r ranging from 0.89 to 0.99) across the six cities.

Comparison of industrial land use across selected cities using different datasets. Our Map (top): Shows industrial land area over built-up surfaces. Official Land Use (middle): Displays designated industrial areas including ports and airports (Singapore) and semi-industrial land use (Nagoya). Local Climate Zone (LCZ10, bottom): Highlights regions classified as heavy industry. The production year for each map is indicated at the bottom. For a detailed explanation of the official land use map, see Supplementary Table 1.

Association between our proposed industrial land area ratio (%) and the official data-based industrial land area ratio (%) for six representative cities. Ratios were calculated within a 5 km grid inside city boundaries. Official industrial land data were rasterized to 30 m from the original vector file. Port/airport areas in Singapore and semi-industrial areas in Nagoya, classified in the official data, were excluded from both datasets for calculation due to mixed land use. The grey line represents the linear regression, with the correlation (r) indicated.

Our produced map tends to show more small-sized industrial land areas than the official data. Some regions that are classified as industrial lands on our map were absent from the official data. Visual analysis shows that these areas have a high concentration of industrial buildings. This discrepancy could stem from security concerns, especially in Ulsan, South Korea, which might restrict certain industrial areas from public view. Furthermore, regions with mixed land use, such as industrial and commercial, can be mis-classified as industrial in our data. Among the six cases, Nairobi exhibited a relatively lower correlation (r = 0.89), which could be attributed to the official map being created in 2010, while our map represents data from 2017. This highlights the potential of our produced map to offer updated industrial land-use information for cities where official data is either outdated or rarely updated.

We also compared the heavy industry regions (LCZ10) between our map and the official data (Fig. 7). We found that LCZ10 areas did not cover the entire industrial land area in the city. Our map included heavy industry regions and depicted a wider variety of industrial land types, similar to the official data.

Validation of industrial land map using CO2 emissions data

To assess the reliability of our industrial land mapping, we examined its alignment with CO2 emissions data. Specifically, we calculated industrial land area per capita for 1,093 cities in 2020 and evaluated its correlation with per capita CO2 emissions from fossil fuel combustion. The results show a strong correlation (r = 0.72, Fig. 9), supporting the consistency of our mapped industrial land distribution with emissions patterns.

Association between industrial land area per capita and CO2 emissions per capita across 1,093 cities in 2020 (mid-year of the study period), both plotted on a logarithmic scale. The correlation coefficient (r) is shown in the bottom right. CO2 emissions are derived from the Open-Data Inventory for Anthropogenic Carbon Dioxide51.

Additionally, we compared this correlation with that of built-up surface area per capita—an indicator used in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)56,57—which showed a lower correlation with CO2 emissions (r = 0.57) (see Supplementary Figure 6). This comparison further supports the validity of our industrial land mapping, as it aligns well with a key environmental indicator.

Limitations

Despite achieving high mapping accuracy, our approach to industrial land modeling has several limitations. The construction of reference data primarily relied on the OSM land use data, which is based on human annotations and inherently contains uncertainties58. We used built-up surface data to select stable reference samples for modeling maps from 2017 to 2023, assuming no land use transitions occurred within the same built-up area during this period. However, this assumption may overlook transitions, such as shifts from commercial or residential to industrial land use. Although these transitions may be insignificant, and the random forest algorithm is relatively robust to this type of noise59, this limitation could introduce errors, especially for the earlier years of analysis.

Another limitation is the temporal coverage of certain input datasets. While most input parameters are updated annually, we used the GHSL datasets—non-residential built-up surface area and non-residential building volume—which follow a 5-year update cycle. These datasets are relevant for capturing industrial land characteristics, with 2020 serving as the midpoint of our study period (2017–2023) and aligning well with our analysis timeframe. However, the less frequent temporal updates of these datasets may introduce minor inconsistencies. To mitigate this, we applied a spatial and temporal filtering method to reduce potential noise and improve the stability of the results.

Our datasets could not precisely distinguish mixed land use areas, such as those combining commercial and industrial uses, are often classified as industrial, which users of our data should take caution. Our mapping framework also depends on the quality of built-up surface datasets, which may propagate errors originating from the underlying dataset.

Code availability

The code is available at the following github repository: https://github.com/cheolheeyoo/Industriallandmapping.

References

Leigh, N. G. & Hoelzel, N. Z. Smart growth’s blind side: Sustainable cities need productive urban industrial land. Journal of the American Planning Association 78, 87–103 (2012).

Li, D., Yang, L., Lin, J. & Wu, J. How industrial landscape affects the regional industrial economy: A spatial heterogeneity framework. Habitat International 100, 102187 (2020).

Chapple, K. The highest and best use? Urban industrial land and job creation. Economic Development Quarterly 28, 300–313 (2014).

Kozhevina, O. V., Trifonov, P. V., Ksenofontov, A. A. & Perednikh, L. V. The strategic management of sustainable industrial development in transition to Industry 4.0. Growth Poles of the Global Economy: Emergence, Changes and Future Perspectives, 1295–1304 (2020).

Zhou, L., Tian, L., Cao, Y. & Yang, L. Industrial land supply at different technological intensities and its contribution to economic growth in China: A case study of the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region. Land Use Policy 101, 105087 (2021).

Ji, S. & Ma, S. The effects of industrial pollution on ecosystem service value: A case study in a heavy industrial area, China. Environment, Development and Sustainability 24, 6804–6833 (2022).

Lei, T. et al. Global iron and steel plant CO2 emissions and carbon-neutrality pathways. Nature 622, 514–520 (2023).

Li, Q., Chen, W., Li, M., Yu, Q. & Wang, Y. Identifying the effects of industrial land expansion on PM2. 5 concentrations: A spatiotemporal analysis in China. Ecological Indicators 141, 109069 (2022).

Portela, C. I., Massi, K. G., Rodrigues, T. & Alcântara, E. Impact of urban and industrial features on land surface temperature: Evidences from satellite thermal indices. Sustainable Cities and Society 56, 102100 (2020).

Wu, S., Hu, S. & Frazier, A. E. Spatiotemporal variation and driving factors of carbon emissions in three industrial land spaces in China from 1997 to 2016. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 169, 120837 (2021).

Xia, C. et al. Exploring potential of urban land-use management on carbon emissions—a case of Hangzhou, China. Ecological Indicators 146, 109902 (2023).

Yang, Q. et al. Atmospheric emissions of respirable quartz from industrial activities in China. Nature Sustainability, 1–8 (2024).

Zhao, C. et al. Atmospheric emissions of hexachlorobutadiene in fine particulate matter from industrial sources. Nature Communications 15, 4737 (2024).

Fan, P. et al. The spatial restructuring and determinants of industrial landscape in a mega city under rapid urbanization. Habitat International 95, 102099 (2020).

Huang, L. et al. Characterizing spatial patterns and driving forces of expansion and regeneration of industrial regions in the Hangzhou megacity, China. Journal of Cleaner Production 253, 119959 (2020).

Yoo, C., Xiao, H., Zhong, Q.-w. & Weng, Q. Unequal impacts of urban industrial land expansion on economic growth and carbon dioxide emissions. Communications Earth & Environment 5, 203 (2024).

Brown, C. F. et al. Dynamic World, Near real-time global 10 m land use land cover mapping. Scientific Data 9, 251 (2022).

Marconcini, M. et al. Outlining where humans live, the World Settlement Footprint 2015. Scientific Data 7, 242 (2020).

Zhang, X. et al. GISD30: Global 30-m impervious surface dynamic dataset from 1985 to 2020 using time-series Landsat imagery on the Google Earth Engine platform. Earth System Science Data Discussions 2021, 1–29 (2021).

Zhou, Y. & Weng, Q. Building up a data engine for global urban mapping. Remote Sensing of Environment 311, 114242 (2024).

He, Q. & Tang, X. Identification and analysis of industrial land in China based on the point of interest data and random forest model. Frontiers in Environmental Science 10, 907383 (2022).

Huang, L. et al. Quantifying the spatiotemporal dynamics of industrial land uses through mining free access social datasets in the mega Hangzhou Bay region, China. Sustainability 10, 3463 (2018).

Huang, L., Xiang, S. & Zheng, J. Fine-Scale Monitoring of Industrial Land and Its Intra-Structure Using Remote Sensing Images and POIs in the Hangzhou Bay Urban Agglomeration, China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, 226 (2022).

Mustak, S., Baghmar, N. & Singh, S. Prediction of industrial land use using linear regression and MOLA techniques: a case study of Siltara industrial belt. Acta Geographica Debrecina Landscape & Environment series 9, 59–70 (2015).

Song, W., Chen, M. & Tang, Z. A 10-m scale chemical industrial parks map along the Yangtze River in 2021 based on machine learning. Scientific Data 11, 843 (2024).

Wang, Z., Zhao, J., Lin, S. & Liu, Y. Identification of Industrial Land Parcels and Its Implications for Environmental Risk Management in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei Urban Agglomeration. Sustainability 12, 174 (2019).

Huang, X. et al. 30 m global impervious surface area dynamics and urban expansion pattern observed by Landsat satellites: From 1972 to 2019. Science China Earth Sciences 64, 1922–1933 (2021).

Sun, Z. et al. Global 10-m impervious surface area mapping: A big earth data based extraction and updating approach. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 109, 102800 (2022).

Guzder-Williams, B., Mackres, E., Angel, S., Blei, A. M. & Lamson-Hall, P. Intra-urban land use maps for a global sample of cities from Sentinel-2 satellite imagery and computer vision. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems 100, 101917 (2023).

Florczyk, A. et al. Description of the GHS urban centre database 2015. Public release https://doi.org/10.2905/53473144-b88c-44bc-b4a3-4583ed1f547e (2019).

Deng, X. et al. Characteristics of surface urban heat islands in global cities of different scales: Trends and drivers. Sustainable Cities and Society 107, 105483 (2024).

Li, X. et al. Mapping global urban boundaries from the global artificial impervious area (GAIA) data. Environmental Research Letters 15, 094044 (2020).

Schneider, A., Friedl, M. A. & Potere, D. Mapping global urban areas using MODIS 500-m data: New methods and datasets based on ‘urban ecoregions’. Remote sensing of environment 114, 1733–1746 (2010).

Liu, X. et al. High-spatiotemporal-resolution mapping of global urban change from 1985 to 2015. Nature Sustainability 3, 564–570 (2020).

Pasquarella, V. J., Brown, C. F., Czerwinski, W. & Rucklidge, W. J. in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 2125–2135.

Wei, W. et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics of energy-related CO2 emissions in China based on nighttime imagery and land use data. Ecological Indicators 131, 108132 (2021).

Pesaresi, M. & Politis, P. GHS-BUILT-S R2023A - GHS built-up surface grid, derived from Sentinel2 composite and Landsat, multitemporal (1975-2030). Joint Research Centre (JRC) European Commission https://doi.org/10.2905/9F06F36F-4B11-47EC-ABB0-4F8B7B1D72EA (2023).

Pesaresi, M. & Politis, P. GHS-BUILT-V R2023A - GHS built-up volume grids derived from joint assessment of Sentinel2, Landsat, and global DEM data, multitemporal (1975-2030). Joint Research Centre (JRC) European Commission https://doi.org/10.2905/AB2F107A-03CD-47A3-85E5-139D8EC63283 (2023).

Arderne, C., Zorn, C., Nicolas, C. & Koks, E. Predictive mapping of the global power system using open data. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3538890 (2020).

Hawker, L. et al. A 30 m global map of elevation with forests and buildings removed. University of Bristol https://doi.org/10.5523/bris.25wfy0f9ukoge2gs7a5mqpq2j7 (2021).

Demuzere, M. et al. A global map of Local Climate Zones to support earth system modelling and urban scale environmental science. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6364594 (2022).

Zhang, X. et al. Development of a global 30 m impervious surface map using multisource and multitemporal remote sensing datasets with the Google Earth Engine platform. Earth System Science Data 12, 1625–1648 (2020).

Wang, F., Wang, Y., Ji, X. & Wang, Z. Effective macrosomia prediction using random forest algorithm. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, 3245 (2022).

Yilmazer, S. & Kocaman, S. A mass appraisal assessment study using machine learning based on multiple regression and random forest. Land use policy 99, 104889 (2020).

Zhao, L., Wu, X., Niu, R., Wang, Y. & Zhang, K. Using the rotation and random forest models of ensemble learning to predict landslide susceptibility. Geomatics, Natural Hazards and Risk 11, 1542–1564 (2020).

Cho, D., Yoo, C., Im, J. & Cha, D. H. Comparative assessment of various machine learning‐based bias correction methods for numerical weather prediction model forecasts of extreme air temperatures in urban areas. Earth and Space Science 7, e2019EA000740 (2020).

Ho, H. C. et al. Mapping maximum urban air temperature on hot summer days. Remote Sensing of Environment 154, 38–45 (2014).

Li, Z., Weng, Q., Zhou, Y., Dou, P. & Ding, X. Learning spectral-indices-fused deep models for time-series land use and land cover mapping in cloud-prone areas: The case of Pearl River Delta. Remote Sensing of Environment 308, 114190 (2024).

Reynolds, R., Liang, L., Li, X. & Dennis, J. Monitoring annual urban changes in a rapidly growing portion of northwest Arkansas with a 20-year Landsat record. Remote Sensing 9, 71 (2017).

Liu, Z. et al. Global patterns of daily CO2 emissions reductions in the first year of COVID-19. Nature Geoscience 15, 615–620 (2022).

Oda, T., Maksyutov, S. & Andres, R. J. The Open-source Data Inventory for Anthropogenic CO 2, version 2016 (ODIAC2016): a global monthly fossil fuel CO 2 gridded emissions data product for tracer transport simulations and surface flux inversions. NIES https://doi.org/10.17595/20170411.001 (2018).

Yoo, C., Zhou, Y. & Weng, Q. Dataset of ‘Mapping 10-m Industrial Lands across 1000+ Global Large Cities, 2017–2023’. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14832219 (2025).

Byers, L. et al. Global power plant database. World Resources Institute https://datasets.wri.org/datasets/global-power-plant-database (2019).

McCarten, M. et al. Global database of iron and steel production assets. Spatial Finance Initiative https://www.cgfi.ac.uk/spatial-finance-initiative/geoasset-project/iron-and-steel (2021).

Grant, D., Hansen, T., Jorgenson, A. & Longhofer, W. A worldwide analysis of stranded fossil fuel assets’ impact on power plants’ CO2 emissions. Nature Communications 15, 7517 (2024).

Bakker, V., Verburg, P. H. & van Vliet, J. Trade-offs between prosperity and urban land per capita in major world cities. Geography and Sustainability 2, 134–138 (2021).

Wang, H., Liu, Y., Sun, L., Ning, X. & Li, G. Assessment of Chinese urban land-use efficiency (SDG11. 3.1) utilizing high-precision urban built-up area data. Geography and Sustainability (2024).

Zhou, Q., Wang, S. & Liu, Y. Exploring the accuracy and completeness patterns of global land-cover/land-use data in OpenStreetMap. Applied Geography 145, 102742 (2022).

Maas, A. E., Rottensteiner, F. & Heipke, C. A label noise tolerant random forest for the classification of remote sensing data based on outdated maps for training. Computer Vision and Image Understanding 188, 102782 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support of the Global STEM Professorship by the Hong Kong SAR Government and the financial support of the Institute of Land and Space at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.Y. played a key role in conceptualizing and developing the methodology framework, coding the model, and analyzing the data. C.Y. also spearheaded the writing of the initial manuscript draft and participated in later revisions, in addition to visualizing the data. Y.Z. assisted with the methodology and offered essential feedback that influenced the direction of the research. Q.W. was crucial in the project’s conceptualization and supervision, provided continuous guidance during the research, and assisted with the writing and revision of the manuscript. Furthermore, Q.W. was instrumental in funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yoo, C., Zhou, Y. & Weng, Q. Mapping 10-m Industrial Lands across 1000+ Global Large Cities, 2017–2023. Sci Data 12, 278 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04604-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04604-w