Abstract

Lucinidae, renowned as the most diverse chemosymbiotic invertebrate group, functions as a sulfide cleaner in coastal ecosystems and is thus ecologically important. Despite their significance, genomic studies on these organisms have been limited. Here, we present the chromosome-level genome assembly of Indoaustriella scarlatoi, an intertidal lucinid clam. Employing both short and long reads, and Hi-C sequencing, we assembled a 1.58 Gb genome comprising 690 contigs with a contig N50 length of 9.00 Mb, which were anchored to 17 chromosomes. The genome exhibits a high completeness of 95.4%, as assessed by the BUSCO analysis. Transposable elements account for 56.02% of the genome, with long terminal repeat retrotransposons (LTR, 42.66%) being the most abundant. We identified 34,469 protein-coding genes, 74.43% of which were functionally annotated. This high-quality genome assembly serves as a valuable resource for further studies on the evolutionary and ecological aspects of chemosymbiotic bivalves.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Lucinidae (Bivalvia: Lucinida) is the most species-rich family of chemosymbiotic invertebrates1. All known species of this bivalve family have established symbiotic relationships with chemosynthetic Gammaproteobacteria2,3. Lucinids are widely distributed in marine ecosystems, ranging from 70° N to 55° S, including intertidal zones, shallow-water, and deep-sea sediments4. Previous studies have demonstrated the evolution of deep-sea bivalves to chemosymbiosis5,6,7, but coastal ones may have different adaptations due to the higher availability of photosynthetic matter in coastal ecosystems than the deep-sea habitats. However, the specific evolutionary adaptations of coastal bivalves to chemosymbiosis remain largely unknown. Furthermore, Lucinidae and Thyasiridae (Lucinida) have long been considered as closely related groups due to the shared morphological features. However, phylogenetic trees based on rRNA genes supported the monophyletic status of each group8, and genomic studies of both Thyasiridae7 and Lucinidae species will further promote the understanding of these questions.

Lucinids have been proved to play a pivotal ecological role in coastal ecosystems. Through large-scale genomic studies, coastal lucinid symbionts mainly belong to the genus Ca. Thiodiazotropha and are universally capable of sulfur oxidation and carbon fixation9,10, enabling the lucinid holobionts to effectively remove sulfides from sediment. The presence of lucinid clams significantly reduces the concentration of sulfides in sediment, as demonstrated in either mesocosm or field experiments11,12,13. This process is crucial for maintaining the health of plants in coastal areas, as high levels of hydrogen sulfide can severely affect the development of the roots of seagrasses and mangroves11,14. Therefore, lucinids and their bacterial symbionts are of great ecological importance in coastal ecosystems11.

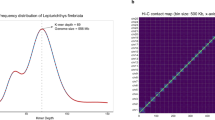

Despite lucinids’ significant importance in the fields of evolution and ecology, the lack of genomic data has hindered the study of their phylogenetic relationships, evolutionary adaptations, and the regulatory mechanisms behind their ecological functions. Here, we assembled the chromosome-level genome of Indoaustriella scarlatoi (Lucinidae) based on reads of whole genome sequencing (WGS), PacBio HiFi sequencing, and Hi-C sequencing (Table 1). The I. scarlatoi genome is 1.58 Gb in size, containing 690 contigs with a N50 length of 9.00 Mb (Table 2). After Hi-C scaffolding, 99.41% of contigs were anchored to 17 chromosomes with a scaffold N50 length of 94.81 Mb (Tables 2, 3, Fig. 1). The mapping rate of WGS reads is 98.15%. In total, 938 genes, including 911 complete ones, of the 954 metazoan Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO) were successfully located in the final assembly, indicating that the genome completeness is 95.4% (Table 2). The transposable elements occupied 56.02% of the genome, while LTR accounted for 42.66% of the genome (Table 4). We predicted 34,469 protein-coding genes in the I. scarlatoi genome, and 74.43% of these genes can be functionally annotated using at least one public database (Table 5). The ncRNA including tRNA, rRNA, miRNA, and snRNA were annotated with a total length of 1.35 Mb (Table 6). Overall, the I. scarlatoi genome is of high quality and will provide a valuable resource for studies on phylogeny and adaptive evolution.

Methods

Sampling and sequencing

Individuals of Indoaustriella scarlatoi were collected from peri-mangrove sediment in Wenchang, China (19°24′44″ N, 110°44′50″ E). Samples were fixed using RNAlater (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and stored at −80 °C.

The muscle tissue of one individual was used to extract the total DNA for WGS and PacBio HiFi sequencing. Genomic DNA was extracted using QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen). For WGS, Covaris E220 was used to fragment DNA, and DNA fragments around 200 bp were selected using AMPure XP beads (Beckman). Selected fragments were amplified for eight PCR cycles and sequenced on the DNBSEQ sequencing platform (BGI) in a paired-end 150 bp layout (Table 1). Long-read sequencing was performed on the PacBio Sequel II system (PacBio). After examining the DNA using Qubit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and pulsed field electrophoresis system (BioRad), a 15-kb PacBio library was constructed by g-TUBE (Covaris) shearing, end-repair, and BluePippin (Sage Science) size selection. Two SMART cells were sequenced through circular consensus sequencing (CCS) mode (Table 1). For Hi-C library construction, cells dissociated from I. scarlatoi’s muscle tissue were crosslinked with 1% formaldehyde and 0.2 M glycine. The fixed powder was resuspended in nuclei isolation buffer and then incubated in 0.5% SDS for 10 min at 62 °C, and the nuclei were collected by centrifugation. The DNA in the nuclei was digested with MboI (NEB), and the overhang was filled and biotinylated prior to ligation by T4 DNA ligase (NEB). After purification, DNA was sheared, and biotin-containing fragments were captured using Dynabeads MyOne Streptavidin T1 (Invitrogen). The captured DNA was then amplified and sequenced with NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina) with a layout of paired-end 150 bp (Table 1). To better annotate the genome assembly, RNA-seq of tissues from a whole clam was performed. Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol (Invitrogen) and used to generate cDNA with HiscriptII (Vazyme). The cDNA fragments were sequenced on the DNBSEQ platform, and 7.32 Gb 150 bp paired-end data was generated.

Genome assembly and Hi-C scaffolding

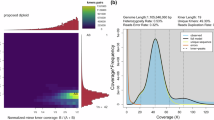

Genome survey was conducted with WGS data using Jellyfish v2.2.615 at K-mer 17, and the estimated genome size of I. scarlatoi was 1.48 Gb while the heterozygosity was 1.69%. The genome was assembled with PacBio data by hifiasm v0.16.1 (-k 45 -r 2 -a 2 -m 2,000,000 -p 20,000 -l 0)16. After that, the PacBio long-reads was realigned to the assembly using minimap2 v2.1417, and duplications in the assembly were removed using Purge_Dups v1.2.3 (https://github.com/dfguan/purge_dups) with default parameters. Kraken218 was used to identify potential contaminant contigs, and contigs assigned to Bacteria were removed. The decontaminated contig-level assembly was assessed using BUSCO v5.2.219 with metazoan odb10 (Table 2). The quality control of Hi-C data was performed using HiC-Pro v3.220 (Table 1), and assembled contigs was then scaffolded by 3D-DNA21. Assembled chromosomes were visualized and adjusted in Juicebox v1.922, and 99.41% of the contigs were anchored to 17 chromosomes (Table 3, Fig. 1A). The final assembly is 1.58 Gb with a scaffold N50 length of 94.81 Mb (Table 2, Fig. 1B).

Repeat and gene annotation

Tandem repeats were annotated using Tandem Repeats Finder v4.0.7 with MaxPeriod set as 200023. Transposable elements (TEs) were identified with both homology-based and de novo prediction methods. LTR_Finder v1.0.624 with parameters “-C” and RepeatModeler v1.0.825 with default parameters were used for de novo search. For homology-based search, RepeatMasker v4.0.626 was employed to search against Repbase v21.0127 with parameters “-nolow -norna -no_is” and results of de novo search (Table 4).

Ab initio, homology-based and gene expression evidence were combined to annotate protein-coding genes. Augustus v3.128 was used for ab initio gene prediction. Blast v2.2.2629 was used to align gene sets from 10 molluscan species (Archivesica marissinica6, Argopecten concentricus30, Conchocele bisecta7, Crassostrea gigas31, Gigantidas platifrons5, Lutraria rhynchaena32, Mactra quadrangularis33, Margaritifera margaritifera34, Modiolus philippinarum5, Pecten maximus35) onto the genome of I. scarlatoi, and the alignment hits were linked to candidate gene region by GenBlastA36. GeneWise v2.2.037 was employed to determine gene models with sequences of the candidate gene and their 2-kb flanking regions. RNA-seq data were mapped to the genome assembly by HISAT v2.1.038, and Stringtie v1.3.439 and Transdecoder v5.7.1 (github.com/TransDecoder/TransDecoder) with parameters “--complete_orfs_only” were used to generate the gene annotation with transcripts evidence. EVM v1.1.140 was employed to integrate the results generated by the three methods with parameters “--segmentSize 5000000 --overlapSize 200000”, and the weights for integrating were “AUGUSTUS 1, GeneWise 3, transdecoder 10”. All annotated protein-coding genes were searched against the following databases: Swiss-Prot v201709, KEGG v87.0, InterPro v55.0, and TrEMBL v201709 (Table 5). Completeness of the gene set was assessed using BUSCO v5.2.219 (Table 2).

ncRNA (non-coding RNA), including tRNA, rRNA, snRNA, and miRNA were predicted. tRNAscan-SE-1.3.141 were used to predict tRNAs in the assembly with default parameters. We aligned invertebrate rRNA sequences against the assembly using BLAST software29 with “-e 1e-5”. For miRNA and snRNA annotation, we first aligned the assembly against the Rfam database42 (v14.1) using BLAST software29 (-e 1) to find candidate alignment, and used INFERNAL43 v1.1.1 to annotate snRNAs and miRNAs with default parameters (Table 6).

Data Records

All sequencing data, including WGS, PacBio, Hi-C, RNA-seq, as well as the assembly (JBIWQA000000000)44 have been deposited at the NCBI (National Centre for Biotechnology Information) repository under project PRJNA1181275, SRP54367445. Genome assemblies and annotations of I. scarlatoi are also available at Figshare46.

Technical Validation

The lengths of DNA fragments for PacBio sequencing mainly distributed around 50 kb, and the N50 length of PacBio reads is 17.7 kb. The size of the assembly is 1.58 Gb, while the estimated genome size by Jellyfish is 1.49 Gb. The quality value of the assembly, calculated using Merqury v1.347, was 63.66, indicating high assembly accuracy. The assembled genome contains 690 contigs, which N50 length is 9.0 Mb and N90 is 2.2 Mb. The rate of valid Hi-C reads was 19.36%. After Hi-C scaffolding, 99.41% of the contigs were successfully anchored to 17 chromosomes. BWA (v0.7.17, github.com/lh3/bwa) MEM algorithm was used to align the WGS reads to the final assembly, and the mapping rate was calculated using the flagstat commands of samtools v1.948 with the secondary mapping records removed. The mapping rate of WGS reads was 98.15%. In addition, we aligned RNA-seq data and PacBio HiFi reads against the assembly using hisat238 and minimap217 (“-ax map-hifi”), respectively, and the mapping rates of RNA-seq data were 81.15% while that of the HiFi reads was 99.78%. Using BUSCO software (v5.2.2)19, 938 of 954 BUSCOs were identified in the genome, including 911 complete ones, and the completeness of the final assembly was estimated as 95.4%. Compleasm v0.2.649 was also used to test the completeness of the assembly and the result was 97.7% (Table 2). We used both BUSCO v5.2.219 and OMArk v0.3.050 to evaluate the quality of gene annotation, and the BUSCO score of gene set (95.1%) was similar with that of the assembly, while the OMArk completeness was 90.69%.

Code availability

Custom scripts for the Circos plot have been deposited at Git-hub (github.com/GuoYang-qd/Circos).

References

Taylor, J. D. & Glover, E. A. Lucinidae (Bivalvia)–the most diverse group of chemosymbiotic molluscs. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 148, 421–438, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.2006.00261.x (2006).

Petersen, J. M. et al. Chemosynthetic symbionts of marine invertebrate animals are capable of nitrogen fixation. Nat Microbiol 2, 16195, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.195 (2016).

Lim, S. J. et al. Taxonomic and functional heterogeneity of the gill microbiome in a symbiotic coastal mangrove lucinid species. ISME J 13, 902–920, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-018-0318-3 (2019).

Taylor, J. & Glover, E. Biology, evolution and generic review of the chemosymbiotic bivalve family Lucinidae. (2021).

Sun, J. et al. Adaptation to deep-sea chemosynthetic environments as revealed by mussel genomes. Nat Ecol Evol 1, 121, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-017-0121 (2017).

Ip, J. C. et al. Host-Endosymbiont Genome Integration in a Deep-Sea Chemosymbiotic Clam. Mol Biol Evol 38, 502–518, https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msaa241 (2021).

Guo, Y. et al. Hologenome analysis reveals independent evolution to chemosymbiosis by deep-sea bivalves. BMC Biol 21, 51, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12915-023-01551-z (2023).

Taylor, J. D., Williams, S. T. & Glover, E. A. Evolutionary relationships of the bivalve family Thyasiridae (Mollusca: Bivalvia), monophyly and superfamily status. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 87, 565–574, https://doi.org/10.1017/s0025315407054409 (2007).

Osvatic, J. T. et al. Global biogeography of chemosynthetic symbionts reveals both localized and globally distributed symbiont groups. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2104378118 (2021).

Osvatic, J. T. et al. Gene loss and symbiont switching during adaptation to the deep sea in a globally distributed symbiosis. ISME J 17, 453–466, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-022-01355-z (2023).

van der Heide, T. et al. A three-stage symbiosis forms the foundation of seagrass ecosystems. Science 336, 1432–1434, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1219973 (2012).

Chin, D. W. et al. Facilitation of a tropical seagrass by a chemosymbiotic bivalve increases with environmental stress. Journal of Ecology 109, 204–217, https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.13462 (2020).

van der Geest, M., van der Heide, T., Holmer, M. & de Wit, R. First Field-Based Evidence That the Seagrass-Lucinid Mutualism Can Mitigate Sulfide Stress in Seagrasses. Frontiers in Marine Science 7, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2020.00011 (2020).

Li, H. et al. Unraveling hydrogen sulfide-promoted lateral root development and growth in mangrove plant Kandelia obovata: insight into regulatory mechanism by TMT-based quantitative proteomic approaches. Tree Physiology 41, 1749–1766, https://doi.org/10.1093/treephys/tpab025 (2021).

Marçais, G. & Kingsford, C. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics 27, 764–770, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btr011 (2011).

Cheng, H., Concepcion, G. T., Feng, X., Zhang, H. & Li, H. Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nature methods 18, 170–175 (2021).

Li, H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 34, 3094–3100 (2018).

Wood, D. E., Lu, J. & Langmead, B. Improved metagenomic analysis with Kraken 2. Genome biology 20, 1–13 (2019).

Seppey, M., Manni, M. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO: Assessing Genome Assembly and Annotation Completeness. Methods Mol Biol 1962, 227–245, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-9173-0_14 (2019).

Servant, N. et al. HiC-Pro: an optimized and flexible pipeline for Hi-C data processing. Genome biology 16, 1–11 (2015).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicer provides a one-click system for analyzing loop-resolution Hi-C experiments. Cell systems 3, 95–98 (2016).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicebox provides a visualization system for Hi-C contact maps with unlimited zoom. Cell systems 3, 99–101 (2016).

Benson, G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic acids research 27, 573–580 (1999).

Xu, Z. & Wang, H. LTR_FINDER: an efficient tool for the prediction of full-length LTR retrotransposons. Nucleic Acids Res 35, W265–268, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkm286 (2007).

Smit, A. F. & Hubley, R. (2008).

Smit, A. F. Repeat-Masker Open-3.0. http://www.repeatmasker.org (2004).

Jurka, J. et al. Repbase Update, a database of eukaryotic repetitive elements. Cytogenetic and genome research 110, 462–467 (2005).

Stanke, M. et al. AUGUSTUS: ab initio prediction of alternative transcripts. Nucleic acids research 34, W435–W439 (2006).

Ye, J., McGinnis, S. & Madden, T. L. BLAST: improvements for better sequence analysis. Nucleic acids research 34, W6–W9 (2006).

Liu, X. et al. Draft genomes of two Atlantic bay scallop subspecies Argopecten irradians irradians and A. i. concentricus. Scientific Data 7, 99, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-020-0441-7 (2020).

Zhang, G. et al. The oyster genome reveals stress adaptation and complexity of shell formation. Nature 490, 49–54, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11413 (2012).

Thai, B. T. et al. Whole Genome Assembly of the Snout Otter Clam, Lutraria rhynchaena, Using Nanopore and Illumina Data, Benchmarked Against Bivalve Genome Assemblies. Front Genet 10, 1158, https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2019.01158 (2019).

Sun, Y. et al. A high-quality chromosome-level genome assembly of the bivalve mollusk Mactra veneriformis. G3 (Bethesda) 12, https://doi.org/10.1093/g3journal/jkac229 (2022).

Gomes-dos-Santos, A. et al. The Crown Pearl: a draft genome assembly of the European freshwater pearl mussel Margaritifera margaritifera (Linnaeus, 1758). DNA research 28, dsab002 (2021).

Kenny, N. J. et al. The gene-rich genome of the scallop Pecten maximus. Gigascience 9, https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giaa037 (2020).

She, R., Chu, J. S.-C., Wang, K., Pei, J. & Chen, N. GenBlastA: enabling BLAST to identify homologous gene sequences. Genome research 19, 143–149 (2009).

Birney, E., Clamp, M. & Durbin, R. GeneWise and genomewise. Genome research 14, 988–995 (2004).

Kim, D., Paggi, J. M., Park, C., Bennett, C. & Salzberg, S. L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nature biotechnology 37, 907–915 (2019).

Pertea, M. et al. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nature biotechnology 33, 290–295 (2015).

Haas, B. J. et al. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the Program to Assemble Spliced Alignments. Genome biology 9, 1–22 (2008).

Lowe, T. M. & Eddy, S. R. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic acids research 25, 955–964 (1997).

Kalvari, I. et al. Rfam 14: expanded coverage of metagenomic, viral and microRNA families. Nucleic Acids Research 49, D192–D200 (2021).

Nawrocki, E. P. & Eddy, S. R. Infernal 1.1: 100-fold faster RNA homology searches. Bioinformatics 29, 2933–2935 (2013).

NCBI GenBank http://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc:JBIWQA000000000 (2024).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP543674 (2024).

Guo, Y., Zhong, Z., Zhang, N., Wang, M. & Li, C. Chromosome-level genome assembly of the intertidal lucinid clam Indoaustriella scarlatoi. Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27755760 (2024).

Rhie, A., Walenz, B. P., Koren, S. & Phillippy, A. M. Merqury: reference-free quality, completeness, and phasing assessment for genome assemblies. Genome biology 21, 1–27 (2020).

Li, H. et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352 (2009).

Huang, N. & Li, H. compleasm: a faster and more accurate reimplementation of BUSCO. Bioinformatics 39, btad595 (2023).

Nevers, Y. et al. Quality assessment of gene repertoire annotations with OMArk. Nature Biotechnology, 1–10 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42030407, No. 42076091), the Marine S&T Fund of Shandong Province for Pilot National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology (Qingdao) (No.2022QNLM030004), the NSFC Innovative Group Grant (No. 42221005), and the State Key Laboratory of Microbial Technology Open Projects Fund (Project NO. M2023-10). We appreciate all the assistance provided by the crews on RV Kexue.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.G. and M.W. conceived the idea. Z.Z. collected the sample. Y.G. and N.Z. performed the experiments. Y.G. performed the analysis and wrote the manuscript. M.W. and C.L. supervised the study. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, Y., Zhong, Z., Zhang, N. et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly of the intertidal lucinid clam Indoaustriella scarlatoi. Sci Data 12, 275 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04606-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04606-8