Abstract

Algal blooms, which have become increasingly prevalent worldwide over the past decade, significantly impact on water quality and aquatic organisms. Filter-feeding fish are used to control phytoplankton and improve the ecological quality of water bodies. Mud carp (Cirrhinus molitorella) is a freshwater cyprinid species that predominantly consumes algae. Here, we generated a high-quality chromosome-level assembly of C. molitorella by integrating PacBio and Hi-C sequencing strategies. The genome assembly is 1.05 Gb, with a contig N50 of 24.13 Mb and a scaffold N50 of 39.38 Mb. The Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO) (v4.0.5) benchmark of genome assembly reached 97.4% (95.8% single-copy). The consensus quality value (QV) and k-mer completeness of the C. molitorella assembly evaluated by Merqury software were 30.35 and 92.16%, respectively. The construction of the C. molitorella genome provides a valuable genetic resource that will facilitate the investigation of the digestion mechanism of filter-feeding fish.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Over the past decade, algal blooms have become increasingly prevalent worldwide due to the intensified anthropogenic activity1. Algal blooms have emerged as one of the most severe environmental issues affecting inland water2. The accumulations of harmful algae, including cyanobacteria, profoundly impacts water quality and disrupt aquatic ecosystems by increasing turbidity, depleting oxygen, and competing with other organisms3,4. Additionally, it is well-documented that certain phytoplankton species can generate toxic secondary metabolites that are harmful to the health of aquatic animals5. Studies have shown that silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) and bighead carp (Hypophthalmichthys nobilis) ingest large amounts of toxic algae during periods of rapid growth6,7, suggesting these two species have developed specialized mechanisms to counteract the adverse effects of algal toxins8. Thus, these two filter-feeding fish are used to control phytoplankton and improve the ecological quality of water bodies9,10.

Mud carp (Cirrhina molitorella) is a freshwater cyprinid species distributed in southern China, Vietnam, the Philippines, and Thailand11. This species primarily inhabits midwater to bottom depths in large and medium-sized rivers, often venturing into flooded forests during the rainy season. It predominantly consumes algae, benthic organisms, and organic detritus by scraping sediment surface12. C. molitorella is one of the four major carp species cultivated in southern China, contributing to approximately one-third of the total commercial landings in the Pearl River13. Recently, high-quality genome assemblies of H. molitrix and H. nobilis have been constructed to study the genetic basis of the filter-feeding habits of these two closely related carp species14,15. Generating the genome sequence of C. molitorella facilitates the investigation of filter-feeding habits through comparative genomic analysis of filter-feeding cyprinid species from different genera.

Here, we constructed a chromosome-level genome assembly of C. molitorella by integrating PacBio, Illumina, and Hi-C sequencing strategies. The assembled sequences were anchored to 25 pseudo-chromosomes with a scaffold N50 of 39.38 Mb. BUSCO (v4.0.5) evaluation showed that the final assembly achieved 97.4% completeness. The high-quality genome assembly of C. molitorella serves as a valuable genomic resource for exploring digestive mechanisms of filter-feeding fish and provides genetic resources for developing molecular breeding program for this important aquaculture species.

Methods

Sample preparation and genome sequencing

All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Sun Yat-Sen University. All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering. No wild C. molitorella individual as well as endangered or protected species was used in this study. One female C. molitorella individual, collected from a farm in Guangzhou, Guangdong Province, China, was used for genome sequencing. High-quality DNA was extracted from liver cells of C. molitorella using the CTAB method, followed by purification with QIAGEN Genomic kit (QIAGEN, Germany). The sequencing libraries were constructed and purified using AMPure PB beads (Pacific Biosciences, USA). Sequencing was performed on a PacBio Sequel II instrument (Pacific Biosciences, USA). For Illumina sequencing, short-insert paired-end (PE) (150 bp) DNA libraries of C. molitorella were constructed in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Sequencing of PE libraries were performed on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina, USA). A total of 200.26 Gb of PacBio reads and 100.79 Gb of Illumina reads were generated (Supplementary Table 1 and 2). Genomic DNA for the Hi-C library was extracted from liver tissue, and the Hi-C library was constructed based on a previously published procedure and sequenced (2 × 150 bp) on the Illumina NovaSeq. 6000 platform (Illumina, USA)16. A total of 142.43 Gb of Hi-C reads were generated (Supplementary Table 3).

Eye, brain, gill, heart, stomach, intestine, kidney, liver, and spleen samples were collected from the C. molitorella specimen to construct sequencing libraries for RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq). Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, USA). RNA-seq libraries were constructed using a VAHTSTM mRNA-seq V2 Library Prep Kit for Illumina (Vazyme, China) and sequenced (2 × 150 bp) on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina, USA).

Genome size estimation and genome assembly

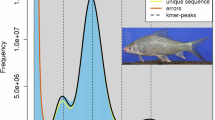

The genome sizes of C. molitorella were estimated using high-quality Illumina reads based on k-mer frequency distribution with the Kmer_freq_hash module in GCE (v1.0.0) (https://github.com/fanagislab/GCE), with k-mer set to 17. Based on the k-mer distribution of Illumina reads, the genome sizes of C. molitorella were estimated to be 1.03 Gb (Supplementary Figure 1).

Three draft genome assemblies were generated using filtered and corrected Nanopore reads with WTDBG2 (v2.5)17, Flye (v2.7)18, and NextDenovo (v1.0)19. The contigs of the WTDBG2- and Flye-generated draft assemblies were error-corrected using high-quality Illumina reads with Pilon (v1.23)20. The NextDenovo-generated contigs were error-corrected using high-quality Illumina reads with Nextpolish (v1.2.4)21. The resulted contigs were assembled into longer sequences using quickmerge (v0.3)22 and corrected using high-quality Illumina reads with Pilon (v1.23)20. Hi-C reads were used to correct misjoins, order and orient contigs, and merge overlaps. Low-quality Hi-C reads were filtered using Fastp (v0.21.0)23. Filtered Hi-C reads were aligned to the assembled contigs using Juicer (v1.5.7)24. Scaffolding was accomplished using 3D-DNA pipeline (v180419)25. Juicebox (v1.9.9)26 was used to modify the order and direction of certain scaffolds in a Hi-C contact map and to help determine chromosome boundaries. Gaps in the assembled scaffolds were closed using filtered PacBio and Illumina reads with TGS-GapCloser (v1.0.1)27. The final genome assembly of C. molitorella was composed of 229 scaffolds (contig N50: 24.13 Mb, scaffold N50: 39.38 Mb) assembled into 25 pseudochromosomes, resulting in a total assembly size of 1.05 Gb (Fig. 1; Table 1; Supplementary Figure 2; Supplementary Table 4). The resulted pseudochromosomes were aligned to zebrafish genome assembly using NGenomeSyn (v1.0.1)28 (Supplementary Figure 3), and the pseudochromosomes were subsequently named according to the alignment results.

The completeness of the assembled genome was assessed using Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO)29. BUSCO (v4.0.5) analysis indicated that 97.4% of conserved single-copy ray-fin fish (Actinopterygii) genes (odb10) were captured in the C. molitorella genome (Supplementary Table 5). Additionally, the consensus quality value (QV) and k-mer completeness of the C. molitorella assembly, evaluated by Merqury software, was 30.35 and 92.16%, respectively (Supplementary Table 6)30. Finally, RNA-seq reads from different tissues were aligned to the assembly. The average mapping rates of RNA-seq reads of 10 tissues to the C. molitorella genome assembly was 92.27% (Supplementary Table 7). These results suggest that the C. molitorella assembly is of high quality and completeness.

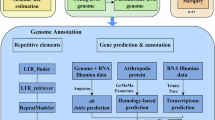

Repeat annotation

Repetitive elements in the C. molitorella assembly were identified through de novo predictions using RepeatMasker (v4.1.0) (https://www.repeatmasker.org/). RepeatModeler (v2.0.1)31 was used to build the de novo repeat libraries. To identify repetitive elements, sequences from the assembly were aligned to the de novo repeat library using RepeatMasker (v4.1.0). Additionally, repetitive elements in the C. molitorella genome assembly were identified by homology searches against known repeat databases using RepeatMasker (v4.1.0). Repetitive DNA represented 529.51 Mb (50.46%) of the C. molitorella genome assembly (Supplementary Table 8). DNA transposons were the largest class of annotated transposable elements (TEs), represented 344.03 Mb (32.79%) of the genome. Retrotransposons accounted for 7.22% of the genome assembly, among which long terminal repeats (LTRs, 4.13%) and long interspersed nuclear elements (LINEs, 2.85%) were the two major classes of retrotransposons. Additionally, a large proportion of unclassified interspersed repeats (7.83%) were identified in the genome.

Gene prediction and functional annotation

Protein-coding genes in the C. molitorella genome were predicted with three approaches: homology-based prediction, ab initio prediction, and RNA-seq-based prediction. For homology-based prediction, protein-coding sequences of Danio rerio, Gasterosteus aculeatus, Oryzias latipes, Takifugu rubripes, Tetraodon nigroviridis, Hypophthalmichthys molitrix, Hypophthalmichthys nobilis, Ctenopharyngodon idella, Onychostoma macrolepis were downloaded from NCBI and aligned to the C. molitorella assembly using tblastn. GenomeThreader (v1.7.0)32 was employed to predict gene models based on the alignment results with an E-value cut-off of 10−5. For ab initio gene prediction, gene models were predicted based on the alignment results of short-read RNA-seq reads using BRAKER2 (v2.1.5)33. For RNA-seq-based prediction, the short-read RNA-seq reads were first aligned to C. molitorella reference sequences using HISAT2 (v2.1.0)34. Gene models were predicted based on the alignment results of HISAT2 using StringTie (v2.1.4)35, and coding regions were identified using TransDecoder (v5.5.0)36. Second, short-read RNA-seq reads of C. molitorella were assembled using Trinity (v2.8.5)37. Finally, Program to Assemble Spliced Alignments (PASA) (v2.5.0)38 was used to predict gene models based on the assembly results of Trinity with StringTie predicted gene models as a reference. Gene models of C. molitorella predicted by BRAKER2, GenomeThreader, and PASA were integrated into a nonredundant consensus-gene set using EVidenceModeler (v1.1.1)38. Genes that were supported by transcriptional evidence or had functional annotation were retained. In total, 36,478 protein-coding genes were identified in the C. molitorella genome (Supplementary Table 9). In the predicted gene models of C. molitorella, BUSCO (v4.0.5) analysis identified 3,284 (90.2%) complete conserved single-copy ray-fin fish (Actinopterygii) genes (odb10) (Supplementary Table 10).

To assign functions to the predicted proteins, we aligned the C. molitorella protein models against NCBI nonredundant (NR) amino acid sequences and SwissProt database using BLASTP with an E-value cutoff of 10−5. Protein models were also aligned against the eggNOG database using eggNOG-Mapper39,40. Additionally, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) annotation of the protein models was performed using BlastKOALA41. In total, 36,124 (99.03%) gene models in the C. molitorella genome were annotated in at least one database (NCBI NR, KEGG, GO, and Swiss-Prot) (Supplementary Table 11). Non-coding RNA (ncRNA) in the C. molitorella genome assembly was identified by homology searches against Rfam databases using Infernal (v1.1.4)42 (Supplementary Table 12). The tRNA and UnaL2 LINE 3’ element were the most abundant ncRNAs.

Data Records

Raw reads of genome assemblies are accessible in NCBI under BioProject number PRJNA978961(SRR25058277 and SRR25031768)43,44. The final assembled C. molitorella genome has been deposited in the NCBI GenBank with accession number GCA_040955965.145. The genome assembly, related annotation files, and source files can be accessed through Figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.2435523746.

Technical Validation

BUSCO (v4.0.5)29 evaluation identified 3,544 (97.4%) complete conserved Actinopterygii genes (obd10) in the C. molitorella assembly, suggesting the high completeness of the assembly. Additionally, RNA-seq reads of ten tissues (brain, eye, gill, heart, stomach, intestine, kidney, liver, ovary, and spleen) were aligned to the assembly using HISAT2 (v2-2.1)34. The average mapping rates of RNA-seq reads from these tissues to the C. molitorella genome assembly was 92.27%. Third, Merqury (v1.3)30 was used to assess the completeness and quality of the C. molitorella assembly. The consensus quality value (QV) and k-mer completeness of the assembly evaluated by Merqury software were 30.35 and 92.16%, respectively. Lastly, the quality of the genome annotation was evaluated using the BUSCO (v4.0.5) software. This assessment revealed that the final genome annotation encompassed 90.2% of the actinopterygii_odb10 genes, demonstrating a high completeness rate in gene predictions.

To evaluate the reliability of genome assembly and annotation of C. molitorella, a phylogenetic tree was constructed for C. molitorella and 7 fishes of Cyprinidae. Protein sequences of the 8 species (C. molitorella, C. carpio, C. auratus, Ctenopharyngodon idellus, D. rerio, H. molitrix, H. nobilis, and Puntius tetrazona) were downloaded for phylogenetic analysis. OrthoFinder (v2.5.5)47 was applied to determine orthologous relationship among proteins from subgenome A and subgenome B of C. carpio and C. auratus as well as proteins of P. tetrazona, D. rerio, C. idella, H. molitrix, H. nobilis, C. molitorella. Gene clusters with >100 gene copies in one or more species were removed. Single-copy orthologs in each gene cluster were aligned using MAFFT (v7.487)48. Alignments were trimmed using Gblocks module of PhyloSuite (v1.2.2)49. The phylogenetic tree was constructed with the trimmed alignments using a maximum-likelihood method implemented in IQ-TREE2 (v2.1.2)50 with D. rerio as the outgroup. The best-fit substitution model was selected using the ModelFinder algorithm51. Branch supports were assessed using the ultrafast bootstrap (UFBoot) approach with 1,000 replicates52. The result displayed C. molitorella was sister to subgenome B of both C. carpio and C. auratus as well as P. tetrazona (Fig. 2), supported the view that C. molitorella had a closer relationship to subgenome B of both C. carpio and C. auratus than subgenome A of the cyprinid allotetraploid species53,54.

Code availability

All software and pipelines were executed following the manuals and protocols provided by the published bioinformatic tools. The version and parameters of the software have been described in the Methods section.

References

O’Neil, J. M., Davis, T. W., Burford, M. A. & Gobler, C. J. The rise of harmful cyanobacteria blooms: The potential roles of eutrophication and climate change. Harmful Algae 14, 313–334, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hal.2011.10.027 (2012).

Hou, X. J. et al. Global mapping reveals increase in lacustrine algal blooms over the past decade. Nat Geosci 15, 130–134, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-021-00887-x (2022).

Brooks, B. W. et al. Are harmful algal blooms becoming the greatest inland water quality threat to public health and aquatic ecosystems? Environ Toxicol Chem 35, 6–13, https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.3220 (2016).

Capuzzo, E., Stephens, D., Silva, T., Barry, J. & Forster, R. M. Decrease in water clarity of the southern and central North Sea during the 20th century. Glob Chang Biol 21, 2206–2214, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12854 (2015).

Pearson, L., Mihali, T., Moffitt, M., Kellmann, R. & Neilan, B. On the chemistry, toxicology and genetics of the cyanobacterial toxins, microcystin, nodularin, saxitoxin and cylindrospermopsin. Mar Drugs 8, 1650–1680, https://doi.org/10.3390/md8051650 (2010).

Chen, J., Xie, P., Zhang, D., Ke, Z. & Yang, H. In situ studies on the bioaccumulation of microcystins in the phytoplanktivorous silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) stocked in Lake Taihu with dense toxic Microcystis blooms. Aquaculture 261, 1026–1038, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2006.08.028 (2006).

Chen, J., Xie, P., Zhang, D. & Lei, H. In situ studies on the distribution patterns and dynamics of microcystins in a biomanipulation fish–bighead carp (Aristichthys nobilis). Environ Pollut 147, 150–157, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2006.08.015 (2007).

Cheng, W. et al. Seasonal variation of gut Cyanophyta contents and liver GST expression of mud carp (Cirrhina molitorella) and Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) in the tropical Xiangang Reservoir (Huizhou, China). Chin Sci Bull 57, 615–622, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11434-011-4871-7 (2012).

Datta, S. & Jana, B. B. Control of bloom in a tropical lake: grazing efficiency of some herbivorous fishes. J Fish Biol 53, 12–24, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8649.1998.tb00104.x (1998).

Lin, Q. Q. et al. Predation pressure induced by seasonal fishing moratorium changes the dynamics of subtropical Cladocera populations. Hydrobiologia 710, 73–81, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-012-1260-4 (2013).

Yang, C., Zhu, X. P. & Sun, X. W. Development of microsatellite markers and their utilization in genetic diversity analysis of cultivated and wild populations of the mud carp (Cirrhina molitorella). J Genet Genomics 35, 201–206, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1673-8527(08)60028-4 (2008).

Rainboth, W. J. Fishes of the Cambodian Mekong. (FAO, 1996).

Huang, Y., Chen, F., Tang, W., Lai, Z. & Li, X. Validation of daily increment deposition and early growth of mud carp Cirrhinus molitorella. J Fish Biol 90, 1517–1532, https://doi.org/10.1111/jfb.13250 (2017).

Jian, J. B. et al. Whole genome sequencing of silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) and bighead carp (Hypophthalmichthys nobilis) provide novel insights into their evolution and speciation. Mol Ecol Resour 21, 912–923, https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.13297 (2021).

Zhou, Y., Qin, W. L., Zhong, H., Zhang, H. & Zhou, L. J. Chromosome-level assembly of the Hypophthalmichthys molitrix (Cypriniformes: Cyprinidae) genome provides insights into its ecological adaptation. Genomics 113, 2944–2952, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygeno.2021.06.024 (2021).

Belton, J. M. et al. Hi-C: a comprehensive technique to capture the conformation of genomes. Methods 58, 268–276, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymeth.2012.05.001 (2012).

Ruan, J. & Li, H. Fast and accurate long-read assembly with wtdbg2. Nat Methods 17, 155–158, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-019-0669-3 (2020).

Kolmogorov, M., Yuan, J., Lin, Y. & Pevzner, P. A. Assembly of long, error-prone reads using repeat graphs. Nat Biotechnol 37, 540–546, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0072-8 (2019).

Hu, J. et al. NextDenovo: an efficient error correction and accurate assembly tool for noisy long reads. Genome Biol 25, 107, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-024-03252-4 (2024).

Walker, B. J. et al. Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS One 9, e112963, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0112963 (2014).

Hu, J., Fan, J., Sun, Z. & Liu, S. NextPolish: a fast and efficient genome polishing tool for long-read assembly. Bioinformatics 36, 2253–2255, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btz891 (2020).

Chakraborty, M., Baldwin-Brown, J. G., Long, A. D. & Emerson, J. J. Contiguous and accurate de novo assembly of metazoan genomes with modest long read coverage. Nucleic Acids Res 44, e147, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkw654 (2016).

Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y. & Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, i884–i890, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560 (2018).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicer Provides a One-Click System for Analyzing Loop-Resolution Hi-C Experiments. Cell Syst 3, 95–98, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cels.2016.07.002 (2016).

Dudchenko, O. et al. De novo assembly of the Aedes aegypti genome using Hi-C yields chromosome-length scaffolds. Science 356, 92–95, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aal3327 (2017).

Robinson, J. T. et al. Juicebox.js Provides a Cloud-Based Visualization System for Hi-C Data. Cell Syst 6, 256–258 e251, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cels.2018.01.001 (2018).

Xu, M. et al. TGS-GapCloser: A fast and accurate gap closer for large genomes with low coverage of error-prone long reads. Gigascience 9, https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giaa094 (2020).

He, W. et al. NGenomeSyn: an easy-to-use and flexible tool for publication-ready visualization of syntenic relationships across multiple genomes. Bioinformatics 39, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btad121 (2023).

Simao, F. A., Waterhouse, R. M., Ioannidis, P., Kriventseva, E. V. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31, 3210–3212, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351 (2015).

Rhie, A., Walenz, B. P., Koren, S. & Phillippy, A. M. Merqury: reference-free quality, completeness, and phasing assessment for genome assemblies. Genome Biol 21, 245, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-020-02134-9 (2020).

Flynn, J. M. et al. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117, 9451–9457, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1921046117 (2020).

Gremme, G., Brendel, V., Sparks, M. E. & Kurtz, S. Engineering a software tool for gene structure prediction in higher organisms. Inform Software Tech 47, 965–978, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infsof.2005.09.005 (2005).

Bruna, T., Hoff, K. J., Lomsadze, A., Stanke, M. & Borodovsky, M. BRAKER2: automatic eukaryotic genome annotation with GeneMark-EP+ and AUGUSTUS supported by a protein database. NAR Genom Bioinform 3, lqaa108, https://doi.org/10.1093/nargab/lqaa108 (2021).

Kim, D., Paggi, J. M., Park, C., Bennett, C. & Salzberg, S. L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat Biotechnol 37, 907–915, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0201-4 (2019).

Pertea, M., Kim, D., Pertea, G. M., Leek, J. T. & Salzberg, S. L. Transcript-level expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with HISAT, StringTie and Ballgown. Nat Protoc 11, 1650–1667, https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2016.095 (2016).

Grabherr, M. G. et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat Biotechnol 29, 644–U130, https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.1883 (2011).

Haas, B. J. et al. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nat Protoc 8, 1494–1512, https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2013.084 (2013).

Haas, B. J. et al. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the program to assemble spliced alignments. Genome Biol 9, https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2008-9-1-r7 (2008).

Huerta-Cepas, J. et al. eggNOG 5.0: a hierarchical, functionally and phylogenetically annotated orthology resource based on 5090 organisms and 2502 viruses. Nucleic Acids Res 47, D309–D314, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky1085 (2019).

Huerta-Cepas, J. et al. Fast Genome-Wide Functional Annotation through Orthology Assignment by eggNOG-Mapper. Mol Biol Evol 34, 2115–2122, https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msx148 (2017).

Kanehisa, M., Sato, Y. & Morishima, K. BlastKOALA and GhostKOALA: KEGG Tools for Functional Characterization of Genome and Metagenome Sequences. J Mol Biol 428, 726–731, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2015.11.006 (2016).

Nawrocki, E. P. & Eddy, S. R. Infernal 1.1: 100-fold faster RNA homology searches. Bioinformatics 29, 2933–2935, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btt509 (2013).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR25031768 (2023).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR25058277 (2023).

NCBI GenBank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.gca:GCA_040955965.1 (2024).

Tu, G. X. A chromosome-level genome assembly of the mud carp (Cirrhinus molitorella). Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24355237 (2024).

Emms, D. M. & Kelly, S. OrthoFinder: phylogenetic orthology inference for comparative genomics. Genome Biol 20, 238, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-019-1832-y (2019).

Katoh, K. & Standley, D. M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol 30, 772–780, https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/mst010 (2013).

Zhang, D. et al. PhyloSuite: An integrated and scalable desktop platform for streamlined molecular sequence data management and evolutionary phylogenetics studies. Mol Ecol Resour 20, 348–355, https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.13096 (2020).

Minh, B. Q. et al. IQ-TREE 2: New Models and Efficient Methods for Phylogenetic Inference in the Genomic Era. Mol Biol Evol 37, 1530–1534, https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msaa015 (2020).

Kalyaanamoorthy, S., Minh, B. Q., Wong, T. K. F., von Haeseler, A. & Jermiin, L. S. ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat Methods 14, 587–589, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.4285 (2017).

Hoang, D. T., Chernomor, O., von Haeseler, A., Minh, B. Q. & Vinh, L. S. UFBoot2: Improving the Ultrafast Bootstrap Approximation. Mol Biol Evol 35, 518–522, https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msx281 (2018).

Wang, Y. et al. Comparative genome anatomy reveals evolutionary insights into a unique amphitriploid fish. Nat Ecol Evol 6, 1354–1366, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-022-01813-z (2022).

Luo, J. et al. From asymmetrical to balanced genomic diversification during rediploidization: Subgenomic evolution in allotetraploid fish. Sci Adv 6, eaaz7677, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aaz7677 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Guangdong S&T programme (2024B1212060001, 2024B1212040007), Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Zhuhai) (SML2023SP234), and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, Sun Yat-sen University (23ptpy23).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.W. conceived of the project and designed research; J.H. collected the sample; G.T., Z.Y. and Z.L. assembled and annotated the genomes; G.T., Z.Y., Z.L., Y.L., Z.L., S.W. J.G.H. performed the evolutionary analyses; M.W. and G.T. wrote the paper with contribution from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tu, G., Yan, Z., Zhang, L. et al. A chromosome-level genome assembly of the mud carp (Cirrhinus molitorella). Sci Data 12, 285 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04615-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04615-7