Abstract

The oral microbiome plays a crucial role in maintaining health, with Streptococcus salivarius recognized for its beneficial probiotic functions, including inhibiting pathogenic bacteria and supporting immune regulation, particularly in healthy individuals. While research on S. salivarius has primarily focused on strains originating from non-Asian populations, particularly New Zealand, with some studies also reporting European strains, research on strains originating from Korea has been notably lacking. This dataset provides the complete genome sequences and transcriptomic profiles of 12 S. salivarius strains isolated from healthy Korean individuals. PacBio SMRTbell technology was employed for genome sequencing. Our dataset includes transcriptomic data that reveal functional gene expression patterns under standard growth conditions. The strains analyzed here are particularly valuable as each exhibits a unique interaction with Fusobacterium nucleatum, a pathogen associated with periodontal disease and colorectal cancer, collectively demonstrating diverse patterns of interaction. By offering comprehensive data on strain variation, this resource can serve as a valuable tool for research aimed at understanding and utilizing beneficial oral bacteria.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background and Summary

The human oral microbiome, a complex and diverse ecosystem composed of bacteria, microeukaryotes, archaea, and viruses, plays a critical role not only in oral health but also in overall systemic health through its interactions with the host’s immune system. Bacteria in the genus Streptococcus are among the earliest colonizers of the oral cavity and are typically acquired shortly after birth1. This bacterial group contributes to the maintenance of health and the development of disease in various ways. Among this bacterial group, we focus on Streptococcus salivarius, a dominant, non-pathogenic species known for its positive effects on oral health.

S. salivarius showcases an impressive ability to curb detrimental microorganisms and subtly orchestrate the host’s immune system, positioning it as a promising candidate for both probiotic and postbiotic roles2,3,4. Yet, as often observed in microbial realms, S. salivarius strains vary widely in their capabilities. Among these, several strains show both preventive and therapeutic potential across diverse applications, with strains K12 and M18 — originating from New Zealand — being the most studied and renowned. Strain K12, in particular, exhibits notable efficacy against respiratory pathogens like Streptococcus pyogenes by producing bacteriocins, including salivaricins A2 and B5.Research by Burton et al.2,6 indicates that S. salivarius K12 can inhabit the oral cavity without toxic side effects, where it further aids in reducing inflammation and enhancing oral health by tempering inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and interleukin-8 (IL-8), typically heightened by periodontal pathogens4.

Meanwhile, S. salivarius M18, known for its production of salivaricin 9, has shown inhibitory effects on pathogens like Corynebacterium and S. pyogenes7. Beyond these prominent strains, others — such as S. salivarius TOVE-R from the UK and S. salivarius JIM8772 from Germany — have also proven capable of impeding cariogenic and periodontal pathogens, while modulating immune responses through the downregulation of inflammatory pathways8,9,10.

As of October 1, 2024, 401 S. salivarius genome assemblies have been submitted to the NCBI database. However, most of these remain incomplete, with only 21 assemblies reaching the complete genome or chromosome level, while the rest are still at the contig or scaffold stage. This reflects the challenges in generating fully resolved, high-quality genomic data, particularly for S. salivarius, a species whose genetic diversity is shaped by factors such as host ethnicity, dietary patterns, and other environmental influences. Notably, most of the strains analyzed so far have been derived from non-Asian populations, with a focus on strains from Europe and other Western regions. Additionally, it is worth noting that S. salivarius strains from Koreans, who have a unique food culture, have not yet been studied in detail.

To address this gap, we sequenced the complete genomes of 12 S. salivarius strains isolated from Koreans of various ages. These fully assembled, chromosome-level genomes provide a valuable resource for investigating the genetic diversity of S. salivarius in a population that has not been widely studied genomically, namely the Korean population. Along with the genomic data, our dataset includes transcriptome profiles of these strains cultured under standard laboratory conditions.

Of particular interest, we noted marked differences in how these strains interact in vitro with Fusobacterium nucleatum subsp. nucleatum — a bacterium intimately linked to periodontal disease and recently spotlighted in studies of colorectal cancer and colitis11,12,13. This dataset, in this regard, offers a valuable resource for comparative genomics and transcriptomics, potentially unveiling the underlying mechanisms of these microbial interactions. Furthermore, it lays the groundwork for upcoming research into the probiotic potential of S. salivarius. Figure 1 visually summarizes this study, with comprehensive methodologies detailed in the Methods section.

Methods

Bacterial strain isolation and species identification

Buccal mucosa samples were collected from six Korean individuals across various age groups. The sample collection was conducted in 2016 and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the Dental Hospital of Kyung Hee University (KHD IRB 1606-5). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, and for those unable to provide consent, consent was obtained from their legal guardians. The participants included a 10-year-old male (KSS7 and KSS8), a 5-year-old female (KSS9 and KSS10), a 21-year-old female (KSS2 and KSS3), a 9-year-old female (KSS1 and KSS11), a 33-year-old female (KSS4 and KSS5), and a 36-year-old female (KSS6 and KSS12). All participants were systemically healthy, had no history of antibiotic use in the past three months, and presented no active oral diseases, although they had restoratively treated teeth. Samples were collected using sterile swabs and placed into phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to create bacterial suspensions.

To isolate S. salivarius, 200 µl of each suspension was serially diluted and spread onto Mitis Salivarius agar (MS agar) plates (MB Cell, MB-M0621) supplemented with 1% potassium tellurite (MB Cell, MB-P18452). The plates were incubated at 37 °C in an anaerobic chamber with 10% CO2, 10% H2, and a nitrogen balance for 24 hours. After colony growth, individual colonies were subcultured on BD BACTO™ Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) agar (BD, 237500) to propagate the bacteria further.

Species identification was performed using PCR. DNA was extracted from the colonies using InstaGene™ DNA Purification Matrix (Bio-Rad, 7326030) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The complete 16 S rRNA gene sequence (~ 1.5 kb) was amplified using universal eubacteria primers14. The PCR reaction mixture contained 0.1 µg of template DNA, 0.5 µM of each primer, and 1U of AccuPower® Taq PCR PreMix (Bioneer, K-2606). The concentration of each dNTP was 250 µM, with a total reaction volume of 20 µl. The PCR cycle was as follows: an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 minutes, followed by 30 cycles of 95 °C for 20 seconds, 53 °C for 20 seconds, and 72 °C for 1 minute and 20 seconds. The final extension was performed at 72 °C for 5 minutes. PCR products were purified and sequenced and species identification was performed via a BLAST search against the GenBank database.

DNA extraction, library preparation, and whole genome sequencing

S. salivarius strains were cultured in BHI broth until the OD600 reached 0.5-0.7. The cultures were incubated at 37 °C in an anaerobic chamber. After incubation, the bacterial cells were pelleted by centrifugation, and the supernatant was discarded. DNA was extracted from the pellet using the Axen™ Total DNA BYC Mini Kit (Macrogen. MG-P-006-50). For whole genome sequencing of each S. salivarius strain, a Single-Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) bell library was prepared following the manufacturer’s instructions (Pacific Biosciences). Briefly, 4 μg of input genomic DNA was used for library preparation. The Femto Pulse System (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was employed to assess the actual size distribution for all size quality checks, ensuring the library insert sizes were in the optimal range. We sheared the genomic DNA using the Megaruptor® 3 (Diagenode, Liège, Belgium) and purified it using AMPure PB magnetic beads (Pacific Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA, USA) for size-selection. A total of 10 μL of the library was prepared using PacBio SMRTbell prep kit 3.0. SMRTbell templates were annealed using Sequel II Bind Kit 3.2 and Int Ctrl 3.2. Sequencing was performed using the Sequel II Sequencing Kit 2.0 and SMRT cell 8 M Tray, with 15-hour movie capture for each SMRT cell, on the PacBio Sequel IIe (Pacific Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA, USA) platform by Macrogen Inc. (Seoul, Korea). The subsequent steps are based on the PacBio Sample Net-Shared Protocol. The raw base calling data was generated and then the HiFi reads were generated using the CCS algorithm. The HiFi read statistics was summarized in Table 1 and the distributions of HiFi read length and quality was assessed and presented in Fig. 2.

Genome assembly and pan genome analysis

To perform de novo assembly for the completely circular genomes for S. Salivarius, the SMRT Link software (v12.0.0.177059) for Sequel II system was used. Briefly, the Microbial Genome Analysis pipeline was loaded from pbcromwell wrapper. The parameter for the analysis was “–task-option ipa2_genome_size = 0–task-option ipa2_downsampled_coverage = 0–task-option microasm_plasmid_contig_len_max = 300000–task-option ipa2_cleanup_intermediate_files = True–task-option filter_min_qv = 20”. The 12 completely circular genomes were successfully generated for all 12 S. Salivarius strains. Among them, KSS1 and KSS11 strains have a ~100 kb plasmid in addition to the bacterial chromosome. The NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline was employed for gene annotation process15. All strains have similar size of whole genome and the similar number of genes (Fig. 3 and Table 2). In the process of genome assembly, the method could detect the base modification in the genome. In Table S1, we listed the methylation motifs for each genome. To compare the genomic contents, pan-genomes analysis pipeline (PGAP)16 analysis was performed using gene family method with default parameters (score: 40, e-value: 1 × 10−10, identity: 0.5, and coverage: 0.5). Based on pan-genome profiles, the phylogenetic tree among 13 strains including ATCC 7073 type strain was constructed (Fig. 4a). Interestingly, the strain pairs from the same subject; KSS1 - KSS11, KSS2 - KSS3, KSS4 - KSS5, KSS6 - KSS12, and KSS9 – KSS10 were relatively close each other in the tree. The orthologous gene clusters identified in each strain from the PGAP analysis were categorized into core, dispensable, and strain-specific gene clusters. The pangenome of the twelve S. salivarius strains (Fig. 4b) was composed of 1,446 core gene clusters (54.5%, present in all strains), 771 dispensable gene clusters (29.1%, partially shared among the strains), and 435 strain-specific gene clusters (16.4%).

RNA extraction, library preparation, and whole transcriptome sequencing (RNA-Seq)

S. salivarius strains were grown as described above. After centrifugation, the supernatant was removed, and the bacterial cells were processed using the AccuPrep® Bacterial RNA Extraction Kit (Bioneer, K-3143), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Total RNA concentration was determined using Quant-IT RiboGreen (Invitrogen, #R11490). RNA integrity was evaluated by running the samples on a TapeStation RNA screentape (Agilent). Only RNA samples with a high RNA Integrity Number (RIN) above 7.0 were selected for library construction. For each sample, RNA libraries were individually prepared using 1 μg of total RNA with the Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA Sample Prep Kit (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA, #20020595). As the first step, bacterial rRNA was depleted using the NEBNext rRNA Depletion kit (Bacteria) (NEB). After rRNA depletion, the remaining RNA was broken down into smaller fragments through the use of divalent cations at a high temperature. The resulting RNA fragments were then reverse transcribed into first-strand cDNA using SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) and random primers. Next, second-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using DNA Polymerase I, RNase H and dUTP. The resulting cDNA fragments underwent process of end repair, the addition of a single ‘A’ nucleotide, and adapter ligation. These products were subsequently purified and amplified through PCR to form the final cDNA library. The libraries were quantified using the KAPA Library Quantification kits designed for Illumina Sequencing platforms, following the qPCR Quantification Protocol Guide (KAPA), and further assessed using TapeStation D1000 ScreenTape (Agilent). The indexed libraries were then submitted for paired-end (2 × 101 bp) sequencing on an Illumina NovaSeq. 6000 (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA), which was performed by Macrogen Inc. (Seoul, Korea).

RNA-Seq data processing

In each strain, two biological replicates were sequenced and a total of approximately 388 (an average per sample: 16 million pairs of reads) million pairs of read (2 × 101 bp) were generated. The adapter sequences in the raw reads were trimmed by cutadapt software (v 4.9)17. The trimmed fastq files were assessed by FastQC (v 0.10.1) (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/) and summarized by MultiQC (v 1.25.1) (https://seqera.io/multiqc/) (Fig. 5a). The preprocessed reads were aligned to S. Salivarius ATCC 7073 (type strain) genome using Bowtie2 (v 2.5.4)18 with the parameters, “-k 2–no-discordant”. Around 298 million read pairs (with an average of 12 million pairs per sample) were uniquely mapped and properly paired in the paired-end sequencing mode (Table S2). The uniquely mapped reads were used for calculating read counts for each gene annotated in the S. Salivarius ATCC 7073 RefSeq sequence (GCF_900143035.1). A total 1,914 genes have at least one read mapped on genic regions across all twelve S. salivarius strains. The hierarchical clustering and heatmap based on the normalized counts were generated by DESeq. 2 R package (v 1.30.1)19 (Fig. 5b). As expected, the replicate samples were located to next to each other and similar to the phylogenetic tree based on the genome assembly data, the expression profiles of strain pairs from the same subject were clustered into the same cluster.

Data Records

The PacBio DNA sequencing data for de novo assembly was deposited to NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database and the assembled genomes were available in NCBI GenBank; SRP53765120 (CP14585621, CP14585722), SRP53765323 (CP14586024), SRP53765425 (CP14586126), SRP53765527 (CP14586228), SRP53766329 (CP15084730), SRP53765631 (CP14586332), SRP53765733 (CP14586434), SRP53765835 (CP14586536), SRP53765937 (CP14586638), SRP53766039 (CP14586740), SRP53766141 (CP14585842, CP14585943), SRP53766444 (CP14586845). RNA sequencing data was submitted into NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database and the GEO accession number is GSE27879146.

Technical Validation

Assessment of sequencing data quality

All paired-end RNA-Seq reads (101 bp) generated from Illumina platform, were quality checked by FastQC (v 0.10.1). All RNA-Seq samples showed a mean Phred score of 30 or higher in every position in the read (Fig. 5a). There are decent number of read pairs uniquely mapped onto the genome of ATCC 7073 S. salivarius type strain in all 24 samples. Furthermore, the gene expression patterns of S. salivarius strains obtained from the same biological replicate as well as from the same subject were similar to each other, confirming the high quality of the sequencing.

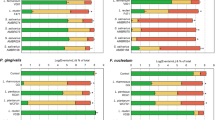

Genome completeness analysis

The de novo assembled genome completeness was checked by BUSCO (v 5.7.1)47 analysis (Fig. 6). The BUSCO is using the predefined bacterial orthologous genes (bacteria_odb10) to evaluate the integrity of the de novo assembled genome. The genome completeness of strains KSS2, KSS5, KSS8, and KSS9 was 98.4%, while the genome completeness of the remaining strains was 99.2%.

Code availability

Bioinformatics tool information and the parameters used in the tool are clearly described in the Methods section. If a parameter is not described, we used the default parameters provided by the tool. No custom code was used for the analysis.

References

Li, K., Bihan, M. & Methe, B. A. Analyses of the stability and core taxonomic memberships of the human microbiome. PLoS One 8, e63139, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0063139 (2013).

Burton, J. P., Chilcott, C. N., Wescombe, P. A. & Tagg, J. R. Extended Safety Data for the Oral Cavity Probiotic Streptococcus salivarius K12. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins 2, 135–144, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12602-010-9045-4 (2010).

Cosseau, C. et al. The commensal Streptococcus salivarius K12 downregulates the innate immune responses of human epithelial cells and promotes host-microbe homeostasis. Infect Immun 76, 4163–4175, https://doi.org/10.1128/IAI.00188-08 (2008).

MacDonald, K. W. et al. Streptococcus salivarius inhibits immune activation by periodontal disease pathogens. BMC Oral Health 21, 245, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-021-01606-z (2021).

Di Pierro, F., Colombo, M., Zanvit, A., Risso, P. & Rottoli, A. S. Use of Streptococcus salivarius K12 in the prevention of streptococcal and viral pharyngotonsillitis in children. Drug Healthc Patient Saf 6, 15–20, https://doi.org/10.2147/DHPS.S59665 (2014).

Burton, J. P., Wescombe, P. A., Moore, C. J., Chilcott, C. N. & Tagg, J. R. Safety assessment of the oral cavity probiotic Streptococcus salivarius K12. Appl Environ Microbiol 72, 3050–3053, https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.72.4.3050-3053.2006 (2006).

Burton, J. P. et al. Influence of the probiotic Streptococcus salivarius strain M18 on indices of dental health in children: a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Med Microbiol 62, 875–884, https://doi.org/10.1099/jmm.0.056663-0 (2013).

Baty, J. J., Stoner, S. N. & Scoffield, J. A. Oral Commensal Streptococci: Gatekeepers of the Oral Cavity. J Bacteriol 204, e0025722, https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.00257-22 (2022).

Kaci, G. et al. Anti-inflammatory properties of Streptococcus salivarius, a commensal bacterium of the oral cavity and digestive tract. Appl Environ Microbiol 80, 928–934, https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.03133-13 (2014).

Van Hoogmoed, C. G. et al. Reduction of periodontal pathogens adhesion by antagonistic strains. Oral Microbiol Immunol 23, 43–48, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-302X.2007.00388.x (2008).

Fan, Z. et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum and its associated systemic diseases: epidemiologic studies and possible mechanisms. J Oral Microbiol 15, 2145729, https://doi.org/10.1080/20002297.2022.2145729 (2023).

Lin, S. et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum aggravates ulcerative colitis through promoting gut microbiota dysbiosis and dysmetabolism. J Periodontol 94, 405–418, https://doi.org/10.1002/JPER.22-0205 (2023).

Wang, N. & Fang, J. Y. Fusobacterium nucleatum, a key pathogenic factor and microbial biomarker for colorectal cancer. Trends Microbiol 31, 159–172, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2022.08.010 (2023).

Srinivasan, R. et al. Use of 16S rRNA gene for identification of a broad range of clinically relevant bacterial pathogens. PLoS One 10, e0117617, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0117617 (2015).

Tatusova, T. et al. NCBI prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline. Nucleic Acids Res 44, 6614–6624, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkw569 (2016).

Zhao, Y. et al. PGAP: pan-genomes analysis pipeline. Bioinformatics 28, 416–418, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btr655 (2012).

Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet.journal 17, 3, https://doi.org/10.14806/ej.17.1.200 (2011).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 9, 357–359, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.1923 (2012).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq. 2. Genome Biol 15, 550, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 (2014).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP537651 (2024).

NCBI GenBank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc:CP145856 (2024).

NCBI GenBank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc:CP145857 (2024).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP537653 (2024).

NCBI GenBank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc:CP145860 (2024).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP537654 (2024).

NCBI GenBank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc:CP145861 (2024).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP537655 (2024).

NCBI GenBank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc:CP145862 (2024).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP537663 (2024).

NCBI GenBank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc:CP150847 (2024).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP537656 (2024).

NCBI GenBank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc:CP145863 (2024).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP537657 (2024).

NCBI GenBank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc:CP145864 (2024).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP537658 (2024).

NCBI GenBank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc:CP145865 (2024).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP537659 (2024).

NCBI GenBank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc:CP145866 (2024).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP537660 (2024).

NCBI GenBank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc:CP145867 (2024).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP537661 (2024).

NCBI GenBank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc:CP145858 (2024).

NCBI GenBank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc:CP145859 (2024).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP537664 (2024).

NCBI GenBank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc:CP145868 (2024).

NCBI GEO https://identifiers.org/geo/GSE278791 (2024).

Manni, M., Berkeley, M. R., Seppey, M., Simao, F. A. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO Update: Novel and Streamlined Workflows along with Broader and Deeper Phylogenetic Coverage for Scoring of Eukaryotic, Prokaryotic, and Viral Genomes. Mol Biol Evol 38, 4647–4654, https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msab199 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science & ICT (NRF-2021R1A2C2008180).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.-H.M. and J.-H.L. conceived and supervised the study. E.Y.J. performed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. J.-H.L. analyzed the data. All authors gave final approval and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jang, EY., Moon, JH. & Lee, JH. Complete genome and transcriptome datasets of Streptococcus salivarius strains from healthy Korean subjects. Sci Data 12, 296 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04619-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04619-3