Abstract

This report presents an open-source dataset investigating neurodevelopmental profiles in children. The dataset consists of EEG, ERP, and cognitive assessments from 100 Iranian non-clinical participants (age range 6–11 years, Mean = 8.52 ± 1.5 SD). Notably, this is a smaller group drawn from a larger longitudinal ongoing study. The research aligns with the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) framework, aiming to enhance diagnostic precision and intervention efficacy for specific learning disabilities (SLD) using EEG/ERP measures and machine learning. Cognitive assessments included non-verbal intelligence (Raven Test), attention (IVA-2), and working memory tasks. EEG recordings captured resting-state (eyes closed/open) and brain activity during working memory tasks with numerical and non-numerical stimuli (ERPs). Additionally, demographic information such as age, gender, education, handedness, parental history of learning difficulties, and child symptom inventory-4 (CSI-4) were collected. This dataset provides a valuable resource for exploring the neurophysiological correlates of cognitive functions in typically developing children, which can advance our understanding of the neural foundations of cognitive development in children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Children aged 6 to 12 undergo a crucial developmental stage that profoundly influences fundamental cognitive processes, affecting both their academic performance and overall mental well-being1,2. Challenges such as learning disabilities, attention and memory issues, and mood disorders can significantly impact various aspects of their lives during this period3. Recognizing the importance of this developmental stage, it is crucial to address and resolve these issues proactively1.

In accordance with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5), specific learning disabilities (SLD) are characterized by unexpected difficulties persisting for at least six months in reading, writing, and mathematics. Dyslexia refers to a specific deficiency in word recognition and decoding, leading to reading impairments4. On the other hand, dyscalculia manifests as deficiencies in number fact knowledge and computation, impacting arithmetic skills5. The estimated prevalence of dyslexia and dyscalculia is approximately 5-12% and 3.5–6.5% among children, respectively6.

This study aligns with the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) project, a National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) initiative launched in 2008. RDoC aims to develop a more precise classification system for mental disorders by linking observable behaviors with underlying neural functions7. Departing from conventional classifications like DSM and International Classification of Diseases (ICD), RDoC seeks to improve diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis for psychiatric disorders by identifying the biological underpinnings of mental illness8.

The conventional DSM classification, relying on semiotics and behavioral symptoms, often leads to delayed diagnosis of SLD in children, missing the crucial window for effective interventions and hindering their learning and development9. Research emphasizes the importance of early intervention, as it is far more effective than addressing issues after academic difficulties arise10. The RDoC framework offers a novel approach by considering phenotypic diversity in speech, cognitive functions, and social functioning in these children11. This shift towards a biological understanding of SLD has the potential to improve diagnosis accuracy, enabling earlier intervention and leading to better learning outcomes.

Learning disabilities are associated with deficits in areas such as phonological processing, working memory, numerical magnitude processing, attention, and processing speed12. While studies have identified various brain dysfunctions in children with SLD, researchers are actively searching for valid neuromarkers (biological indicators) within their nervous systems. Event-Related Potentials (ERPs) offer advantages due to their high temporal resolution, providing a detailed map of brain information processing during cognitive tasks13. This high temporal resolution is important for understanding the precise timing of neural activity potentially disrupted in SLD.

This project employs a combined longitudinal and cross-sectional study design, focusing on children aged 6 and above with a two-year follow-up to observe developmental changes. Investigating neural correlates of working memory, attention, and emotional problems in children with SLD using EEG/ERP recordings, the study aims to identify markers distinguishing dyslexia, dyscalculia, and typical development. This early and accurate diagnosis will be crucial for implementing effective, targeted interventions for SLD. To achieve this objective, we are developing a machine learning-based classification system for SLD subtypes (dyslexia, dyscalculia) prediction using EEG/ERP and behavioral data. Ultimately, this research aspires to translate the findings into a practical protocol for early SLD detection in clinical settings, facilitating timely interventions and improved learning outcomes.

Methods

Participants

A subset of 100 participants (mean age = 8.52 ± 1.5 SD) was drawn from a larger, ongoing longitudinal study. Detailed demographic information, including gender and age distribution, is provided in Table 1. Data were collected from Tehran (and Karaj), and Tabriz cities of Iran.

According to the primary goal of the project, children aged 6 were specifically recruited for the longitudinal study, while older children were included in the cross-sectional study. Special emphasis has been placed on enrolling an adequate number of participants within the 6-year-old age group to ensure robust data for the longitudinal study. The data collection for this segment of the study is expected to continue for approximately two years.

Ethics

Prior to participation in the study, all participants’ parents or legal guardians received both verbal and written information about the research. Informed consent, designed under the supervision of the ethical committee, was voluntarily obtained from them. The informed consent process included detailed explanations about the study procedures, the devices used, safety precautions, and the data sharing policy. Ethical approval for data collection and sharing, while ensuring the preservation of participants’ personal information, was obtained from the regional ethics committees of the University of Tabriz (permit No: IR.TBZMED.RCE.1401.069) and Iran University of Medical Sciences (permit No: IR.IUMS.REC.1401.349) for Tabriz and Tehran (including Karaj), respectively.

Exclusion criteria

Both longitudinal and cross-sectional participants were excluded if they had any medical conditions, neurological diseases, or psychiatric disorders. This criterion is particularly important for the follow-up study of the 6-year-old group, as it aims to identify children with potential learning disorders, which, according to DSM diagnostic criteria, must not be confounded by auditory, visual, motor, intellectual, neurological, or psychiatric disorders.

Procedure

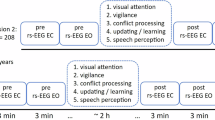

Participants were randomly selected from preschools and schools affiliated with the Ministry of Education. The sequence of the tasks conducted with participants is outlined in Fig. 1. Initially, each participant received a unique code for identification throughout the study. The Raven’s Progressive Matrices (commonly referred to as the Raven test) was administered in a child-friendly manner to establish rapport between children and the experimenter. This initial step typically lasted around 20 minutes. If the child showed no signs of fatigue, they were guided to a dedicated recording room for EEG assessment. Resting-states (rs) EEG recordings were conducted during two conditions: eyes open (EO) for 4 minutes and eyes closed (EC) for 4 minutes. Then, children were instructed to complete two working memory tasks for the recording of their ERPs. The order of the tasks was counterbalanced to mitigate any potential order effects.

Once the EEG/ERP recording was completed, the EEG cap was gently removed, and any residual gel was carefully cleaned from the child’s scalp. Each child was then thanked for their cooperation and offered a break lasting at least 30 minutes, with the option for a longer duration if needed. During this break, all participants had the opportunity to rest and refreshments were provided. Following the break, if the child showed no signs of fatigue and expressed the willingness to proceed, the IVA-2 test was conducted. Throughout these procedures, the parents of each child completed various questionnaires on a tablet, including the Child Symptom Inventory–4 (CSI–4), Edinburgh Handedness Inventory (EHI), Adult Reading History Questionnaire (ARHQ), and Adult Arithmetic History Questionnaire (AAHQ). To express our gratitude for their participation in the study, a comprehensive evaluation of each child’s cognitive and psychological state was offered to their parents. Our team addressed any questions the parents had regarding the assessment and results. All data were collected and analyzed using the NeurokidMap software developed by the Imâge Brain Institute.

Cognitive Tasks

Integrated visual and auditory continuous performance test, second edition (IVA-2)

The Continuous Performance Tests (CPT) is a common paradigm used by researchers and clinicians to assess sustained and selective attention. The IVA-2, a unique CPT, stands out by simultaneously testing auditory and visual performance. Normed on a diverse group of over 1,700 participants aged 6 and above, it has demonstrated high sensitivity (92%) and accuracy (90%) in detecting ADHD in children aged 7 to 1214. In a broader age range study (6 to 55), it matched clinical diagnoses 90% of the time and achieved 89% accuracy in identifying non-ADHD cases15.

The IVA-2 involves auditory and visual stimuli: the target “1” and the non-target “2.” Participants are instructed to respond to the target “1” and to refrain from clicking for the non-target “2.” Each trial consists of one of four stimuli: a target auditory stimulus, a target visual stimulus, and their corresponding non-target counterparts. In total, there are 500 trials, each lasting 1540 ms. The duration of presentation of auditory stimuli is 500 ms and the duration of visual stimuli is 167 ms (Fig. 2). The assessment is structured into four distinct phases: warm-up, practice, main test, and cool-down and takes approximately 15 minutes.

The IVA-2 test provides scores in various categories including response control, attention, attributes, and symptoms. These scores encompass both basic scale scores and composite quotient scores. By analyzing performance nuances within auditory and visual domains, the IVA-2 serves as a comprehensive tool for evaluating attention and response control across different modalities14. Quotient scales provided by the IVA-2 are reported in both Table 2 and Table S2 (see Supplementary Tables).

Raven Colored Progressive Matrices Test (CPM)

The Raven’s CPM is a tool commonly used to assess non-verbal intelligence, especially in children aged 5 to 1116. The CPM measures the ability to induce abstract relations and manage problem-solving goals in working memory17. The test consists of 36 items divided into three sets, using bright colors to engage children. The items are arranged by increasing difficulty18. The CPM might also be beneficial for individuals with reading difficulties19,20, physical handicaps21, or intellectual disabilities22,23,24.

Additionally, the CPM has been found to be stable across different cultural, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups. However, there have been observed variations in norms over time and between ethnic groups within countries18. The CPM has demonstrated good test-retest reliability and sensitivity to fluctuations in intellectual function25,26. Despite some concerns about its reliability in group settings27. the CPM has been found to have good factorial validity and internal consistency28. In this study, we utilized the computerized version of Raven’s CPM test. We provided three measures in this research: raw score, IQ scaled score, and percentile rank (refer to Table 2 and Table S5).

Working memory

Working memory is the capability to simultaneously store and manipulate information for a limited period of time in service of goal-directed behaviors. Working memory is composed of different components: the central executive, which controls and coordinates the other components; the phonological loop, which processes and stores verbal information, such as words and sounds; and the visuospatial sketchpad, which handles visual and spatial information, such as images and mental maps29.

Although phonological processing deficits are accepted as the most dominant concept of the cognitive origin of dyslexia, working memory impairments are also mentioned as one of the most affected cognitive domains. Moreover, dyscalculia is an impairment in processing numerical magnitudes, although deficits in memory, attention, and processing speed have also been reported12. Working memory is regarded as a significant predictor of academic achievement in areas like reading and mathematics and has been suggested to be the cognitive domain that is consistently most affected in SLD children30.

To investigate working memory in more detail, we developed a modified version of the task inspired by recent studies31,32,33. This task specifically targets working memory by integrating visual-spatial and phonological processing through the use of both numerical and non-numerical stimuli. The task consists of two distinct blocks, each designed to assess working memory with different types of stimuli.

In the first block, participants completed 70 trials where they were presented with one-syllable, non-numerical Persian words (e.g., bag, moon). The use of one-syllable words controlled the phonological load on working memory, ensuring that participants focused primarily on the task demands. This approach also standardized conditions, ensured age-appropriateness, and maintained consistency across the experiment.

As illustrated in Fig. 3, each trial in the first block consisted of seven stimuli. Initially, a fixation point (S1) was presented for 200 milliseconds (ms) followed by the presentation of two pictures of one-syllable words within a four-grid square for 3000 ms (S2). Participants were required to memorize these pictures and their locations (which served as the memory set). A visual mask (S3) then appeared for 500 ms to eliminate sensory memory traces. Sequentially presented auditory word stimuli (S4 and S5), recorded under controlled conditions, followed. Participants were also required to memorize these words. After a blank white display with white noise (S6), a test set step (S7) presented two pictures and Participants were required to determine whether these pictures matched the previously memorized pictures from the memory set. Each block lasted approximately 15 minutes.

A visual illustration of a trial in the non-numerical block of the working memory task. Initially, participants are presented with a memory set containing two images within a four-grid square was presented (S2), followed by a visual mask (S3). Participants are then required to memorize the subsequent auditory stimuli (S4 and S5), followed by an auditory mask (S6). In the final step (S7:test set), participants are asked to determine whether the presented pictures matched the memory set (positive set) or not (negative set).

The experiment consisted of 70 trials including 30 positive sets and 40 negative sets. The terms “positive” and “negative” refer to the compatibility of pictures in the test set (S7) with those in the memory set (S2). In the positive sets, the pictures were identical to those that memorized earlier. Conversely, in the negative set pictures differed from the memory set in one of four possible ways: 1) One picture location was changed, 2) Two picture locations were changed, 3) one content alteration was made, or 4) two content alterations were made. Participants were asked to respond quickly and accurately, indicating whether the pictures matched their memory. All trials, both positive and negative, were presented in a pseudo-randomized order, ensuring a consistent format for all participants. This structure facilitated a comprehensive assessment of the participants’ working memory capabilities.

The structure of the second block mirrored that of the first block in terms of task structure, the number of trials, conditions, and instructions. However, the focus shifted to numbers (1 to 4) and dice-distributed dots (see Fig. 4). Participants were once again asked to determine if the test set (S2) corresponded to the memory set (S7). To minimize potential learning effects resulting from a fixed presentation order, the blocks were presented in a random sequence (see Fig. 4).

A visual depiction of the second block (numerical block) in the working memory task. Initially, participants viewed a memory set consisting of two arrangements of dots representing numbers within a four-grid square (S2), followed by a visual mask. Participants were then tasked with memorizing the subsequent auditory stimuli. In the final stage (S7: test set), participants determined whether the displayed numbers corresponded to the memory set (positive set) or not (negative set).

The experiment utilized a 15-inch monitor to present stimuli to participants seated approximately 40 cm away in a dimly lit room. Participants were instructed to respond as quickly and accurately as possible. Prior to the main experiment, practice trials ensured a thorough understanding of the task. No performance feedback was provided during the main experiment. The task was administered using PsyTask software (v. 1.57.21 Mitsar Ltd.). This novel working memory task not only advances our understanding of working memory processes but also provides a versatile tool for future research in this domain.

The behavioral dependent variables of interest in the working memory task were hit rate, false alarm rate and d-prime (d’). These measures are presented in their raw state, as reported in Table 2 and Table S4.

Hit rate

This refers to the proportion of correct responses where the participant correctly identified a target item they were supposed to remember (see Fig. 5).

-

Hit rate is calculated for each negative set condition, positive set condition and for each block separately.

-

The formula is: Hit rate = (number of correct trials in condition X) / (total number of trials in condition X).

-

To obtain an overall hit rate for the negative set conditions within each block, the hit rates are averaged: Hit rate (negative set) = (Hit rate condition 1 + Hit rate condition 2 + Hit rate condition 3 + Hit rate condition 4)/4.

The experimental task and its corresponding markers for ERP analysis. The experiment comprised 70 trials, divided into 40 negative trials and 30 positive trials. In negative set trials, the test picture (S7) differed from the memorized picture (S2) in one of four ways: marker 1 (one location change), marker 2 (two location changes), marker 3 (one content alteration), or marker 4 (two content alterations). For negative set trials, marker 1 in the response channel indicates a hit response, while marker 2 signifies a false alarm. Conversely, in positive trials, the test picture was identical to the memorized picture (marker 5). Here, marker 1 in the response channel denotes a false alarm, and marker 2 indicates a hit response.

False alarm rate

This is the proportion of incorrect responses where the participant mistakenly identified a non-target item as a target item (see Fig. 5).

-

The false alarm rate is calculated in the same way as the hit rate, but for incorrect responses.

-

False alarm rate = (false trials in condition X) / (total trials in condition X).

-

Similar to the hit rate, the false alarm rate for the negative set conditions within each block is calculated by averaging the false alarm rates from each condition.

D-prime (d’)

Signal Detection Theory (SDT) offers a sophisticated approach to assessing performance in cognitive tasks (e. g. working memory task). Unlike traditional measures like hit rate and false alarm rate, which provide limited insights into a participant’s ability to discriminate between targets (signal) and distractors (noise), d-prime offers a more comprehensive evaluation34. While the hit rate quantifies the proportion of correctly identified targets and the false alarm rate reflects the proportion of incorrectly identified distractors, neither measure alone provides a complete picture of a participant’s discrimination ability.

D-prime integrates both the hit rate and false alarm rate into a single metric, offering a more nuanced understanding of a participant’s performance. A higher d-prime value indicates a stronger ability to distinguish between targets and distractors35. This implies better sensitivity and accuracy in working memory task.

-

D-prime is calculated for each condition (positive set and negative set) within a block using the following formula: d’ = z (Hit Rate) - z (False Alarm Rate)36. For example, if the hit rate is 0.8 and the false alarm rate is 0.2, the corresponding z-scores are approximately 0.84 and -0.84, respectively. Thus, d’ = 0.84 - (-0.84) = 1.68, indicating a relatively strong ability to discriminate between targets and distractors.

-

To obtain an average d’ for the negative set condition within a block, individual d’ values are averaged: \(d{\prime} \left({negative\; set}\right)=\,\mathop{\sum }\limits_{i=1}^{4}d{\prime} ({{condition}}_{i})/4\), where ∑ represents the sum.

-

Similarly, to obtain a total d’ for each block is obtained by averaging the d’ values from the negative set and positive set conditions: d’ (block) = (d’ negative set + d’ positive set)/2.

-

Finally, grand total d’ for the entire memory task is calculated by averaging the d’ values from each block: d’ (total) = (d’ block 1 + d’ block 2)/2.

EEG and ERP Data Collection

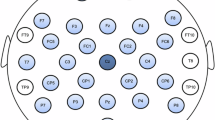

Electrode placement

The EEG cap (Electro-Cap International Inc., OH, USA) was then carefully placed on the child’s head according to the international 10-20 system. EEG data were collected from 19 scalp electrodes (Fp1, Fp2, F3, F4, C3, C4, P3, P4, O1, O2, F7, F8, T3, T4, T5, T6, Fz, Cz, Pz). Ground and reference electrodes (linked ears) were meticulously cleaned. Linked ears served as the reference (left and right earlobes) and the ground electrode was placed at the AFz. A Mitsar 201 amplifier and WinEEG software were employed for data acquisition, with a sampling rate of 250 Hz and a bandpass filter of 0.16 Hz - 70 Hz. To eliminate line noise, a notch filter at 45-55 Hz and 95-105 Hz was noise applied. The conductive gel was then applied to the electrodes, ensuring that electrode impedance was remained below 10 kΩ for each electrode. The reference electrodes were also carefully attached.

Participants were seated in a quiet, well-lit, and sound-attenuated experimental environment, where chairs and tables were adjusted to suit the children’s comfort. To minimize anxiety, parents were permitted to be present in the recording room, positioned discreetly in a corner. Researchers patiently answered any questions from both the children and their parents. The EEG recording consisted of two stages. First, a resting-state stage involved two 4-minute recordings: one with eyes closed and one with eyes open. To minimize eye movement, participants were instructed to fixate on a central point during the open-eye condition and to keep their eyes closed and imagine a fixed point during the closed-eye condition. Second, ERP recording in which participants completed our modified working memory task while EEG data was simultaneously recorded.

Participants received instructions for the memory task and were asked to minimize movement, maintaining stillness during the task presentation. The memory task was visually presented through the PsyTask (Mitsar Ltd.) slave system, while a research associate monitored and recorded EEG data using the master system. The technician continuously monitored the subject’s recordings to prevent contamination of the EEG signal by electromyogram interference, fluctuations in direct current caused by sweating, and potential drowsiness.

QEEG extraction

Quantitative Electroencephalography (QEEG) represents a contemporary approach to EEG analysis, involving the extraction of features from EEG signals to provide a detailed understanding of brain dynamics. These extracted features allow for the analysis of specific frequency bands, signal complexity, functional connectivity, and network-based brain activity37. QEEG utilizes mathematical algorithms to process and analyze digital EEG recordings, transforming raw brainwave activity into quantitative metrics that can be used for clinical or research purposes.

For our study, we employed NeuroGuide software (version 3.2.1, Applied Neuroscience, Inc.) to extract QEEG values. The preprocessing phase began with an extensive visual inspection of the EEG data, conducted to ensure the removal of unwanted artifacts. This included a two-tiered editing approach: automatic detection algorithms were initially applied to flag obvious biological artifacts (such as eye blinks, muscle movements, and heartbeats) and environmental noise (e.g. electrical interference). Subsequently, a manual review was performed to ensure that these artifacts were accurately identified and excluded, minimizing any impact on the data quality and ensuring the integrity of the analysis.

Once artifact-free EEG segments were selected, they were transformed from the time domain into the frequency domain using the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) algorithm. This transformation allowed for a comprehensive spectral analysis, enabling the decomposition of EEG signals into distinct frequency components. The extracted QEEG values were then categorized across several frequency bands, including Delta (1.0–4.0 Hz), Theta (4.0–8.0 Hz), Alpha (8.0–12.0 Hz), Beta (12.0–25.0 Hz), High Beta (25.0–30.0 Hz), Gamma (30.0–40.0 Hz), High Gamma (40.0–50.0 Hz), and sub-bands such as Alpha 1 (8.0–10.0 Hz), Alpha 2 (10.0–12.0 Hz), Beta 1 (12.0–15.0 Hz), Beta 2 (15.0–18.0 Hz), Beta 3 (18.0–25.0 Hz), Gamma 1 (30.0–35.0 Hz), and Gamma 2 (35.0–40.0 Hz).

Seven key features were extracted from the resting-state EEG data under both eyes open and eyes closed conditions, each providing unique insights into the brain’s functional state. These features include: absolute power (the total power within each frequency band, reflecting the overall strength of neural oscillations), relative power (the proportion of power in a given frequency band relative to the total power across all bands, highlighting the distribution of brain activity), power ratio (ratios between different frequency bands, which can reveal imbalances in brainwave activity), peak frequency (the dominant frequency within each band, indicating the rate at which neuronal assemblies are firing), amplitude asymmetry (differences in signal amplitude between homologous brain regions, often used to assess hemispheric imbalances), coherence (a measure of functional connectivity, representing the degree of synchronization between signals from different brain regions), and phase lag (the temporal delay between oscillations from separate brain areas, providing insights into the directionality and efficiency of neural communication).

To aid in the interpretation and clinical relevance of these features, z-scores were calculated using the NeuroGuide software’s normative database. These z-scores allowed for a standardized comparison of an individual’s QEEG values against age-matched norms, helping to identify deviations from typical brain activity patterns. The use of these normative comparisons facilitated a more objective and comprehensive understanding of the brain’s functional state Raw data for all indicators are reported alongside their age-specific z-scores (see Table 2 and Table S1 in Supplementary Tables).

Questionnaires

Child Symptom Inventory–4 (CSI–4)

The CSI-4 is a widely used behavioral rating scale designed to assess symptoms associated with childhood disorders as defined by the DSM-IV criteria. Research supports the reliability and validity of CSI–4 across diverse populations and settings, making it a valuable tool for assessing childhood behavioral and emotional disorders38. In this study, we employed the Persian version of the parent questionnaire, comprising 97 items. All of these scores are reported in raw form (see Table 2 and Table S3 for data information and Appendix 1 (Supplementary Appendices) for CSI–4 items).

Edinburgh Handedness Inventory (EHI)

We used the EHI to evaluate children’s handedness. This scale, consisting 10 items, measures an individual’s preference for using their right or left hand in everyday activities39,40. Additionally, we included two supplementary items to assess the children’s ability to differentiate between right and left and their navigational proficiency. All of these scores are reported in raw form (see Table 2 for data information and Appendix 2 (Supplementary Appendices) for EHI items).

Adult Reading History Questionnaire (ARHQ)

The influence of familial reading history on a child’s literacy development and reading achievements has been extensively studied. Research indicates that children from families with a history of reading difficulties may exhibit poorer letter-word knowledge and phonological awareness41,42. These foundational skills, crucial for future reading success, are typically established before formal education begins43. Additionally, children with a family history of reading difficulties often struggle with word recognition by the time they enter elementary school, impacting their ability to benefit from explicit reading instruction44,45. The ARHQ46 is a reliable screening tool used to assess the risk of dyslexia in adults. The questionnaire consists of 23 items measured on a five-point Likert scale, with higher scores on the ARHQ correspond to a greater likelihood of a familial reading difficulties. By providing insights into the home literacy environment, the ARHQ aids in tailoring interventions to support children’s reading outcomes based on a family history assessment. All of these scores are reported in raw form (see Table 2 for data information and Appendix 3 (Supplementary Appendices) for ARHQ items).

Adult Arithmetic History Questionnaire (AAHQ)

Emerging research suggests a link between family history of math difficulties and a child’s performance in math. Similar to how strong word recognition skills are fundamental for complex reading tasks, arithmetic calculation proficiency is a core skill for math success. This proficiency encompasses the ability to solve single-digit and often multi-digit addition and subtraction problems47,48.

The AAHQ49 is a self-report questionnaire modeled after the ARHQ.It assess the history of arithmetical difficulties in adults46 exploring areas such as basic number knowledge, challenges in learning foundational arithmetic and retrieving arithmetic facts, and the everyday use of numbers and arithmetic. Utilizing a 25-item, five-point Likert scale, higher AAHQ scores indicate a greater likelihood of having math difficulties. All of these scores are reported in raw form (see Table 2 for data information and Appendix 4 (Supplementary Appendices) for AAHQ items).

Data Records

To support and facilitate ongoing research endeavors, we have made dataset available under controlled access at Synapse.org repository50. Researchers interested in accessing the dataset can submit a request following the outlined procedures to ensure compliance with ethical and privacy considerations (see Usage Notes section). This comprehensive dataset includes raw EEG/ERP files, all extracted features from QEEG and ERP, cognitive tasks results, and questionnaires responses. Additionally, Python codes were developed to organize and process the extracted features for researchers’ use. The dataset is structured in three folders as follows:

-

1.

Features extracted from all data:

-

A detailed Tables.docx file provides descriptions of the sample demographic, variable names, QEEG features, test scores, column numbers, and associated details.

-

This dataset is presented as a large matrix file in CSV format, comprising 100 rows (participants) and 34458 columns (variables). The Columns Include:

-

Participant ID: A unique identifier for each participant (1 column).

-

Demographic data: Age, gender, and other related information (5 columns).

-

QEEG Features: Raw and age-adjusted standard scores from rest-state conditions:

-

Eyes Open (EO): 17,100 columns.

-

Eyes Closed (EC): 17,100 columns.

-

-

Cognitive Measures:

-

IVA-2 age-adjusted quotient scores (51 columns).

-

CSI-4 questionnaire raw scores across clinical scales (97 columns).

-

Handedness inventory raw scores (10 columns).

-

Spatial orientation raw scores (2 columns).

-

Parent’s math history raw scores (23 columns).

-

Parent’s reading history raw scores (25 columns).

-

Ravan ‘s Progressive Matrices: raw score, age-adjusted IQ, and percentile rank (3 columns).

-

-

-

-

2.

Raw EEG/ERP data:

-

Raw EEG/ERP recordings in EDF format are provided for all 100 participants within compressed.RAR folders. These include the following:

-

-

Rest-state EEG during the Eyes Closed (EC) condition.

-

Rest-state EEG during the Eyes Open (EO) condition.

-

ERP recordings during the numerical block of the working memory task.

-

ERP recordings during the non-numerical block of the working memory task.

Note: All EEG records have been anonymized by removing personal information to prevent identification of the participants. Participant IDs are consistent across the CSV file and the raw EEG/ERP data files.

-

3.

Software Package:

A Python-based toolkit is included to streamline data analysis, offering functions for reading and filtering cognitive data from the CSV file, along with tools for exporting processed results to facilitate further analysis. This toolkit is designed to assist researchers in efficiently handling the cognitive and EEG/ERP datasets.

Technical Validation

Data quality control and validation for behavioral data

The quality of the behavioral data was ensured through rigorous task design, clear participant instructions, and careful data cleaning. Outliers and errors were identified and removed to maintain data integrity. All data were collected by trained experts under the supervision of a board-certified clinical psychologist. After input, data were organized by a research and development team at the Imâge Brain Institute using statistical summary tools to ensure quality control.

All tests and questionnaires used in this study, except for our novel working memory task, are validated and standardized. Previous studies51 have shown that working memory can mediate the relationship between fluid intelligence, as measured by Raven’s Matrices. As expected, a significant positive correlation was found between performance on our working memory task (i.e. d-prime) and raw score of Raven (r = 0.406, p < 0.0001), supporting the validity of our task. Furthermore, given the expected developmental increase in working memory capacity during ages 6-11, and considering that age was recorded in months to capture finer-grained developmental differences, the significant strong positive correlation between performance on the working memory task and age (in month) (r = 0.629, p < 0.0001) further validates our task’s sensitivity to individual differences in working memory.

Data quality control and validation for EEG

To ensure the highest quality of our EEG data, we employed a comprehensive multi-step approach:

-

1.

Data Acquisition:

-

The EEG cap was carefully placed on the child’s head, ensuring proper fit. Additionally, the distance between the nasion and inion landmarks was measured to ensure accurate placement of the EEG cap according to the international 10-20 system.

-

We carefully monitored electrode impedance levels to minimize noise and artifacts. Impedance values were maintained below 10 kΩ to ensure optimal signal quality.

-

The experimental environment was carefully controlled to reduce the impact of external factors, such as noise, temperature, and lighting, on the EEG recordings.

-

The technicians documented ocular movements and other relevant events during the recording sessions.

-

All technicians were trained experts, qualified in EEG recording procedures.

-

-

2.

Statistical Quality Control: Alpha power suppression is a well-established EEG phenomenon, particularly noticeable at posterior sites during the transition from an eyes-closed to an eyes-open condition52. To visualize these changes, we created a topographic map of alpha power (Fig. 6). This map clearly illustrates a considerable increase in alpha power in the EC condition compared to the EO condition, especially in posterior brain regions.

Data quality control and validation for ERP

Behavioral assessments offer valuable insights into accuracy and reaction time but may not fully elucidate underlying neurocognitive processes. EEG combined with ERPs, with their high temporal resolution (millisecond), offer a valuable tool for investigating these processes capturing neural activity associated with various cognitive functions, such as sensory encoding, inhibition, and working memory53. Previous studies employing ERP analysis in working memory tasks have demonstrated that children with learning disabilities exhibit altered component characteristics, suggesting an increased cognitive effort31,54.

ERP extraction and preprocessing

ERP pre-processing was conducted using the EEGLAB toolbox (ver. R2023a) in MATLAB (The MathWorks, Inc., United States, ver. R2023a), following established protocols and Makoto’s pipelines (Miyakoshi, 2018). EDF + files containing 20 channels (19 EEG, 1 event) were imported. A band-pass filter (0.5-30 Hz) and notch filters (45-55 Hz, 95-105 Hz) were applied to remove noise. Artifact Subspace Reconstruction (ASR) was used to eliminate large artifacts, and Independent Component Analysis (ICA) was employed to remove non-brain sources. Components with a brain source probability exceeding 70% were retained.

ERP Computation

ERPs were computed for each block (numerical and non-numerical). Data were locked to stimulus 1 and averaged across all trials. Data were further averaged according to task condition (negative or positive set). ERPs were computed based on markers 1-4 for negative sets and marker 5 for positive sets (see Fig. 5). ERP waveforms were extracted for all 19 electrodes, covering the entire trial duration.

ERP Analysis

Fig. 7 illustrates ERP activity at the O1 electrode for numerical and non-numerical blocks and conditions (positive and negative sets). ERP patterns for each block revealed activation of working memory components during both memory encoding and test steps for 100 participants. Major components (e.g., P300 and late Posterior Negativity (LPN)) were identified. Notably, the amplitude of LPN was significantly greater for negative sets compared to positive sets [F(1, 99) = 6.132, p = 0.026]. These initial findings suggest potential neural signatures related to type of stimulus (numerical vs. non-numerical) and set type (positive vs. negative) within a working memory task. Aligned with LPN literature55, a significant difference in LPN amplitude between conditions suggests that our task successfully elicited differential neural responses. This indicates that our experimental paradigm was sensitive enough to capture meaningful cognitive processes.

A visual depiction of grand average ERP components elicited during a working memory task. Lines represent average brain activity across participants for the entire trial duration for the numerical block (a) and the non-numerical block (b). Colors distinguish between experimental conditions: positive sets (blue) and negative sets (red). S2 and S7 markers indicate the memory set (encoding) and test set phases of the working memory task, respectively. The amplitude of the LPN component was significantly greater for negative sets compared to positive sets [F(1,99) = 6.132, p = 0.026].

Further investigation and more robust statistical comparisons are warranted to corroborate these initial observations.

Usage Notes

Related information and comprehensive instructions for data usage are provided in the “Accessing the Dataset” wiki tab of the project50. Researchers interested in accessing the dataset should complete the following steps:

-

1.

Register for a Synapse account (www.synapse.org).

-

2.

Become a Synapse Certified and Validated User.

-

3.

Request to Join “Iranian 6-11 Years Population-Based EEG, ERP, and Cognition Dataset Users” Team.To join, the researcher must provide their name and institution in the text box, include their agreement to the Conditions of Use and Intended Data Use Statement, and click the Send Request button. An administrator will review requests within 48 working hours, and confirmation will be sent via email upon approval.

Code availability

The custom code (cognitive_data_utils.py) and data-processing workflows (Read Me.txt) are available in the Software Package folder, located within the Files tab of the project. These resources can be accessed after completing the required steps (see Usage Notes section) via the following link: https://www.synapse.org/Synapse:syn64145789. Follow these steps to utilize the provided toolkit in software package effectively:

1. Clone this repository to your local machine.

2. Ensure you have Python installed on your system.

3. Install the required dependencies by running pip install pandas.

It is important to note that in Python, indices start with 0. Therefore, index = 0 in axis = 1 corresponds to column number 1.

Downstream Processing Steps: Suggested steps for downstream processing and relevant procedures, are outlined as follow:

1. Import the required functions from the toolkit

2. Read the cognitive data from the CSV file

3. Apply filters to the data based on specified criteria

4. Export the filtered data to a new CSV file

References

Eccles, J. S. The Development of Children Ages 6 to 14. The Future of Children 9, 30 (1999).

Sylva, K. Critical periods in childhood learning. British Medical Bulletin 53, 185–197 (1997).

Fusar-Poli, P. Integrated Mental Health Services for the Developmental Period (0 to 25 Years): A Critical Review of the Evidence. Front. Psychiatry 10, 355 (2019).

Vellutino, F. R., Fletcher, J. M., Snowling, M. J. & Scanlon, D. M. Specific reading disability (dyslexia): what have we learned in the past four decades? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 45, 2–40 (2004).

Shalev, R. S., Weirtman, R. & Amir, N. Developmental Dyscalculia. Cortex 24, 555–561 (1988).

Geary, D. C. Consequences, Characteristics, and Causes of Mathematical Learning Disabilities and Persistent Low Achievement in Mathematics. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics 32, 250 (2011).

Cuthbert, B. N. & Insel, T. R. Toward the future of psychiatric diagnosis: the seven pillars of RDoC. BMC Med 11, 126 (2013).

Cuthbert, B. N. Research Domain Criteria: toward future psychiatric nosologies. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 17, 89–97 (2015).

Tomas, E. & Vissers, C. Behind the Scenes of Developmental Language Disorder: Time to Call Neuropsychology Back on Stage. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 12, 517 (2019).

Al Otaiba, S. & Petscher, Y. Identifying and Serving Students With Learning Disabilities, Including Dyslexia, in the Context of Multitiered Supports and Response to Intervention. J Learn Disabil 53, 327–331 (2020).

Musser, E. D. & Raiker, J. S. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: An integrated developmental psychopathology and Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) approach. Comprehensive Psychiatry 90, 65–72 (2019).

Peters, L., Op De Beeck, H. & De Smedt, B. Cognitive correlates of dyslexia, dyscalculia and comorbid dyslexia/dyscalculia: Effects of numerical magnitude processing and phonological processing. Research in Developmental Disabilities 107, 103806 (2020).

Brandeis, D. & Lehmann, D. Event-related potentials of the brain and cognitive processes: Approaches and applications. Neuropsychologia 24, 151–168 (1986).

Sandford, J. A. & Turner, A. IVA+ Plus: Integrated visual and auditory performance test. Toronto, Canada: Brain Train. (2004).

Moreno-García, I., Delgado-Pardo, G. & Roldán-Blasco, C. Attention and Response Control in ADHD. Evaluation through Integrated Visual and Auditory Continuous Performance Test. The Spanish Journal of Psychology 18, E1 (2015).

Raven, J. Coloured Progressive Matrices, Sets A, A_B, B. H. K. Lewis (1962).

Carpenter, P. A., Just, M. A. & Shell, P. What one intelligence test measures: A theoretical account of the processing in the Raven Progressive Matrices Test. Psychological Review 97, 404–431 (1990).

Raven, J. The Raven’s Progressive Matrices: Change and Stability over Culture and Time. Cognitive Psychology 41, 1–48 (2000).

Carver, R. P. Intelligence and reading ability in grades 2–12. Intelligence 14, 449–455 (1990).

Stanovich, K. E., Cunningham, A. E. & Feeman, D. J. Relation between early reading acquisition and word decoding with and without context: A longitudinal study of first-grade children. Journal of Educational Psychology 76, 668–677 (1984).

Martin, A. W. & Wiechers, J. E. Raven’s Colored Progressive Matrices and the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children. Journal of Consulting Psychology 18, 143–144 (1954).

Anderson, H. E., Kern, F. E. & Cook, C. Sex, Brain Damage, and Race Effects in the Progressive Matrices with Retarded Populations. The Journal of Social Psychology 76, 207–211 (1968).

Kilburn, K. L., Sanderson, R. E. & Melton, K. Relation of the Raven Coloured Progressive Matrices to Two Measures of Verbal Ability in a Sample of Mildly Retarded Hospital Patients. Psychol Rep 19, 731–734 (1966).

Stacey, C. L. & Carleton, F. O. The relationship between Raven’s colored progressive matrices and two tests of general intelligence. J. Clin. Psychol. 11, 84–85 (1955).

Cotton, S. M. et al. A normative and reliability study for the Raven’s Coloured Progressive Matrices for primary school aged children from Victoria, Australia. Personality and Individual Differences 39, 647–659 (2005).

Kazlauskaite, V. & Lynn, R. Two-Year Test-Retest Reliability of the Colored Progressive Matrices. Percept Mot Skills 95, 354–354 (2002).

Freyburg, P. S. The Efficacy of The Coloured Progressive Matrices as a Group Test With Young Children. Brit J of Edu Psychol 36, 171–177 (1966).

Abdel-Khalek, A. M. Reliability and Factorial Validity of the Standard Progressive Matrices among Kuwaiti Children Ages 8 to 15 Years. Percept Mot Skills 101, 409–412 (2005).

Baddeley, A. Working memory. Current Biology 20, R136–R140 (2010).

Martínez-Briones, B., Fernández-Harmony, T., Garófalo Gómez, N., Biscay-Lirio, R. & Bosch-Bayard, J. Working Memory in Children with Learning Disorders: An EEG Power Spectrum Analysis. Brain Sciences 10, 817 (2020).

Gutiérrez-Zamora Velasco, G., Fernández, T., Silva-Pereyra, J., Reynoso-Alcántara, V. & Castro-Chavira, S. Higher Cognitive Reserve Is Associated with Better Working Memory Performance and Working-Memory-Related P300 Modulation. Brain Sciences 11, 308 (2021).

Li, D., Christ, S. E. & Cowan, N. Domain-general and domain-specific functional networks in working memory. NeuroImage 102, 646–656 (2014).

Van de Weijer-Bergsma, E., Kroesbergen, E. H., Jolani, S. & Van Luit, J. E. H. The Monkey game: A computerized verbal working memory task for self-reliant administration in primary school children. Behav Res 48, 756–771 (2016).

Hautus, M. J., Macmillan, N. A. & Creelman, C. D. Detection Theory: A User’s Guide. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003203636 (Routledge, New York, 2021).

Witt, J. K. Insights into Criteria for Statistical Significance from Signal Detection Analysis. MP 3 (2019).

Macmillan, N. A. & Creelman, C. Detection theory: a user’s guide. University Press, CambridgeMcFall RM, Treat TA (1999) Quantifying the information value of clinical assessments with signal detection theory. Annu Rev Psychol 50, 215241Oldeld (1991).

Livint Popa, L., Dragos, H., Pantelemon, C., Verisezan Rosu, O. & Strilciuc, S. The Role of Quantitative EEG in the Diagnosis of Neuropsychiatric Disorders. J Med Life 13, 8–15 (2020).

Sprafkin, J., Gadow, K. D., Salisbury, H., Schneider, J. & Loney, J. Further Evidence of Reliability and Validity of the Child Symptom Inventory-4: Parent Checklist in Clinically Referred Boys. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology 31, 513–524 (2002).

Oldfield, R. C. The assessment and analysis of handedness: The Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia 9, 97–113 (1971).

Fazio, R., Coenen, C. & Denney, R. L. The original instructions for the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory are misunderstood by a majority of participants. Laterality: Asymmetries of Body, Brain and Cognition 17, 70–77 (2012).

Carroll, J. M. & Snowling, M. J. Language and phonological skills in children at high risk of reading difficulties. Child Psychology Psychiatry 45, 631–640 (2004).

Pennington, B. F. & Lefly, D. L. Early Reading Development in Children at Family Risk for Dyslexia. Child Development 72, 816–833 (2001).

Storch, S. A. & Whitehurst, G. J. Oral language and code-related precursors to reading: Evidence from a longitudinal structural model. Developmental Psychology 38, 934–947 (2002).

Costa, H. C. et al. Emergent literacy skills, behavior problems and familial antecedents of reading difficulties: A follow-up study of reading achievement from kindergarten to fifth grade. Research in Developmental Disabilities 34, 1018–1035 (2013).

Ehri, L. C. Development of Sight Word Reading: Phases and Findings. in The Science of Reading: A Handbook (eds. Snowling, M. J. & Hulme, C.) 135–154 https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470757642.ch8 (Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Oxford, UK, 2005).

Lefly, D. L. & Pennington, B. F. Reliability and Validity of the Adult Reading History Questionnaire. J Learn Disabil 33, 286–296 (2000).

Fuchs, L. S. et al. The Prevention, Identification, and Cognitive Determinants of Math Difficulty. Journal of Educational Psychology 97, 493–513 (2005).

Jordan, N. C. & Levine, S. C. Socioeconomic variation, number competence, and mathematics learning difficulties in young children. Dev Disabil Res Revs 15, 60–68 (2009).

Sury, D. & Gaab, N. The Adult Arithmetic History Questionnaire. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/zt6ku (2020).

Nazari, M. A. et al. Iranian 6-11 years age population-based EEG, ERP, and cognition dataset. Synapse https://doi.org/10.7303/SYN64112114 (2024).

Heitz, R. P., Unsworth, N. & Engle, R. W. Working Memory Capacity, Attention Control, and Fluid Intelligence. in Handbook of Understanding and Measuring Intelligence 61–78 https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452233529.n5 (SAGE Publications, Inc., 2455 Teller Road, Thousand Oaks California 91320 United States, 2005).

Nazari, M. A., Wallois, F., Aarabi, A. & Berquin, P. Dynamic changes in quantitative electroencephalogram during continuous performance test in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. International Journal of Psychophysiology 81, 230–236 (2011).

Cárdenas, S. Y., Silva-Pereyra, J., Prieto-Corona, B., Castro-Chavira, S. A. & Fernández, T. Arithmetic processing in children with dyscalculia: an event-related potential study. PeerJ 9, e10489 (2021).

Silva-Pereyra, J. et al. Delayed P300 during Sternberg and color discrimination tasks in poor readers. International Journal of Psychophysiology 40, 17–32 (2001).

Sommer, K., Vita, S. & De Pascalis, V. The late posterior negativity in episodic memory: A correlate of stimulus retrieval? Biological Psychology 133, 44–53 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support for this project provided by the Imâge Brain Institute, an Iranian private institute specializing in brain and mental health. We also acknowledge partial funding from the Cognitive Sciences and Technologies Council (permit no: 12286) and the National Institute for Medical Research Development (NIMAD) (permit no: 4001350). Their support was instrumental in the successful completion of this research endeavor. It’s important to note that the funding sources had no influence on the study design, data collection methods, data analysis, or the publication of study results.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Mohammad Ali Nazari, Soomaayeh Heysieattalab, Mohammad Taghi Joghataei. Methodology: Mohammad Ali Nazari, Ali Motie Nasrabadi, Maryam Rezaeian, Sevda Abbasi, Hosein Safakheil. Investigation: Mohammad Ali Nazari, Mohammad Taghi Joghataei, Ali Motie Nasrabadi, Soomaayeh Heysieattalab. Data Curation: Sevda Abbasi, Maryam Rezaeian, Hosein Safakheil, Zohre Asghariyan, Ayda Khayyat Naghadehi, Mahdieh Alizadeh Chakharlou, Parvin Amini Yeganeh, Kiana Azizi, AmirHossein Nasiri, Mohsen Davoudkhani, Mohsen Safakheil, Amirreza Katebi, Masoumeh Hasanzadeh Tahraband, Sahar Delkhahi, Haniyeh Soltani, Vajihe Shahrabi Farahani, Kimia Ghasemkhani, Erfan Nazari. Formal analysis: Ali Motie Nasrabadi, Mohammad Ali Nazari, Zeynab Barzegar, Mohsen Rezaeian. Software: Mohammadreza Alizadeh, Farshid Ghobadzadeh. Visualization: Farshid Ghobadzadeh, Farhad Farkhondeh Tale Navi, Zohre Asghariyan. Writing – original draft: Sevda Abbasi, Maryam Rezaeian, Farshid Ghobadzadeh, Farhad Farkhondeh Tale Navi. Resources: Mohammad Ali Nazari, Haniyeh Soltani, Erfan Nazari. Project administration: Mohammad Ali Nazari. Funding acquisition: Mohammad Ali Nazari, Soomaayeh Heysieattalab, Mohammad Taghi Joghataei. Supervision: Mohammad Ali Nazari, Soomaayeh Heysieattalab, Ali Motie Nasrabadi, Zeynab Barzegar. All contributors critically reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nazari, M.A., Abbasi, S., Rezaeian, M. et al. Iranian 6-11 years age population-based EEG, ERP, and cognition dataset. Sci Data 12, 319 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04624-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04624-6