Abstract

Zoraptera is one of the smallest and least known insect orders, with only 47 described species, mostly known from tropical regions. Data on their distribution remain largely scattered throughout the extensive and often old and/or not easily accessible literature. Recent changes in the supraspecific classification of the order, combined with recent discoveries of new species and other taxonomic changes, have made the understanding of the distribution of Zoraptera even less clear. To summarize and update the knowledge of the worldwide distribution of Zoraptera, we have compiled a data resource of occurrence records: Zoraptera Occurrence Dataset. The dataset contains up-to-date information on the distribution of all zorapteran species according to the latest classification. The dataset is regularly curated and updated with new records from the literature and revised records from iNaturalist and GBIF.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

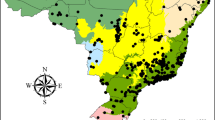

Zoraptera, commonly known as angel insects, is one of the least diverse and least known insect orders1. The extant diversity of Zoraptera is much lower than those of almost all other groups of Hexapoda, with only 47 described species2,3,4,5,6 that are distributed mainly in tropical regions (Fig. 1). The low diversity of Zoraptera might result from poor collection efforts, and the real diversity of this lineage could be highly underestimated1. Consistent with this hypothesis, the first molecular phylogenetic analyses2,7 suggested a high level of cryptic diversity in Zoraptera, which was further confirmed by recent studies focused on taxonomic revisions of individual taxa (e.g.3,4,6). The systematic placement of Zoraptera has always been controversial (e.g.8,9), and various insect lineages, such as Psocoptera, Isoptera, and Embioptera, have been proposed as the closest relatives of Zoraptera (see1 for a review). Recent phylogenomic analyses suggest that Zoraptera is a sister group of Dermaptera10,11,12 or a sister group to the rest of Polyneoptera13. The fossil history of Zoraptera is purely documented14. Because their tiny bodies are not preserved in compression fossils, the oldest known fossils coincide with the oldest available fossiliferous amber (Lower Cretaceous Jordanian amber). However, their long evolutionary history dates back to the Paleozoic7,13,15.

The species diversity and distribution of Zoraptera are poorly understood1,2,7,16, probably due to a combination of factors that make them difficult to collect and study. The tiny zorapterans are small (2–4 mm) and inconspicuous. They live in wood of a certain stage of decomposition under the moist bark of trees in tropical forests of all geographical regions2. There is little material in museums worldwide, although museums deposit material from extensive non-selective collections and various ecological studies conducted in tropical areas. Although independent surveys (e.g.1,3,4) have repeatedly confirmed that zorapterans are abundant and widespread in optimal habitats, collecting them is not easy, because the collecting skills of the researcher must be trained to be effective. The second factor that negatively contributes to their collection is the low attractiveness of zorapterans. Because zorapterans do not attract attention in the field, they are rarely collected during the study of other insects.

Despite a growing interest in the diversity and evolution of Zoraptera2,3,4,5,7, data on their distribution remain largely scattered throughout the extensive and often not easily accessible literature. In addition, the recent dramatic changes in supraspecific classification of the order2 and discoveries of new species3,4,5,6, together with the lack of a modern comprehensive catalog, make the orientation in the Zoraptera literature even less clear. To summarize and update the knowledge on the distribution of Zoraptera worldwide, we compiled a dataset providing a complete and updated resource for future research: Zoraptera Occurrence Dataset. The dataset consists of records from various sources, described in various qualities, from the availability of exact coordinates to vague site descriptions, and for each of these records, we derived geographical coordinates with positional uncertainty. The dataset is a valuable resource, as it provides the most up-to-date information on the distribution of all zorapteran species using the most recent classification. This will encourage and motivate colleagues from all around the world to focus more on this enigmatic insect order. The dataset will continue to be updated, especially with more data from tropical regions, where there are many gaps in our knowledge of zorapteran diversity and distribution.

Methods

To incorporate all species currently classified in this insect order into the dataset, the most recent comprehensive catalog of Zoraptera was utilized17. Subsequently described taxa were then added (e.g.3,4,5,6,18,19,20), while taxa that were not zorapterans were removed21. We followed the currently used and widely accepted higher classification with two families (each with two subfamilies) and ten genera. This classification was recently proposed by Kočárek et al.2 and Kočárek & Kočárková22, and it is based on the results of analyses of molecular phylogeny in combination with morphological characters. The current version of the dataset includes all recent members of the order Zoraptera described before October 1, 2024.

Data sources

The geographical position of each species was obtained from published sources, as well as from material deposited in museum collections and other material collected and/or identified by the authors of this contribution. Additionally, data from iNaturalist23 and GBIF24 were included. Initially, data from all original descriptions of new species was incorporated, and subsequently, all Zoraptera distributional records found in the remaining literature were added. A comprehensive search strategy was employed, encompassing all references cited in the original descriptions as well as in the catalog by Hubbard17, and subsequently, all the references cited in those works were searched. This process was repeated until no new references or occurrence records were identified. To ensure the comprehensiveness of the results, systematic searches were conducted on Google Scholar, Google, and Web of Knowledge using the keyword “Zoraptera” and all supraspecific taxon names historically used in this order (Zorotypidae, Spiralizoridae, Zorotypinae, Spermozorinae, Latinozorinae, Spiralizorinae, Aspiralizoros, Brazilozoros, Centrozoros, Cordezoros, Floridazoros, Latinozoros, Meridozoros, Scapulizoros, Spermozoros, Spiralizoros, Zorotypus, and Usazoros). Therefore, we reviewed not only the taxonomic and faunistic literature, but also studies focusing on the biology, morphology, and phylogeny of Zoraptera (many of which included useful distributional data of the material examined), as well as various general books and other documents. Most publications were in English; rare cases of studies written in other languages (German, Latin, Portuguese, Spanish, Chinese) were analyzed in consultation with colleagues and translated using online translation websites (DeepL or Google Translate). The references included in the final dataset were either those providing original data or, in cases where multiple references reported the same distribution information, only those with the first record or with the most complete information.

All records from iNaturalist have been revised and identified to the lowest possible reliably determinable taxonomic rank directly on the iNaturalist website by Petr Kočárek, and have only imported records with the appropriate license (CC-BY, CC-BY-NC, CC0). GBIF was then queried, excluding iNaturalist data, resulting in a GBIF dataset24 that was further manually revised (see Technical Validation section below for common errors in Zoraptera identification). Specifically, we excluded sequence records imported from genetic databases (Barcode of Life Data System—BOLD, and European Nucleotide Archive—ENA) in all cases when there was no specified voucher specimen deposited in the publicly available collection, fossil records from amber, or records with any geographic information. Finally, we matched the corresponding records by adding a GBIF id to existing records in our dataset and then added the remaining records with revised taxon identification.

Digitizing locations

Information about the geographic location of the records in the available sources was stored in different ways and of varying quality. In all cases, we attempted to derive the most likely accurate coordinates and then determine the degree of positional uncertainty. If the record already had the coordinates, the coordinates were converted to decimal degree format, and the uncertainty was set based on the coordinate precision according to Wieczorek25. In cases where coordinates were missing or not uninterpretable and only a record description was available, we obtained the coordinates by digitizing the areas based on all available information, including maps in publications. To find locations by name or address, we used the Nominatim geocoding tool, which searches for features in OpenStreetMap (OSM) data26. The digitizing process was conducted in QGIS 3.3827. We used Nominatim in QGIS using the plugin OSM place search 1.4.528, which enabled us to import OSM geometry features with attributes directly to QGIS for further processing. We followed the Georeferencing Quick Reference Guide29, and each record was treated separately and carefully based on the context of the environment; i.e., we excluded from the digitized area areas that we felt would be more appropriate for description in the collector’s situation, such as a major city or other notable geographic feature. We used OSM geometry features in various ways based on the amount of available information and the context surrounding the target area, e.g., if there was little information, such as the name of the state or city or only part of it, we used the exact OSM feature. In other cases, the OSM feature was edited or only used as a reference point, e.g., if the location was described as ‘near’ or using distance and direction from the given location. The identification numbers (ids) of the original OSM features were stored in the dataset and could be retrospectively examined and compared. If the record site could not be localized with Nominatim, we used other sources such as Google Maps or various sites and publications reached with Google search and digitized manually or used corresponding OSM features. If altitude was considered, we used OpenTopoMap30 to derive the area corresponding to the altitude. If the description referred to a line or point feature (e.g., a road, river, hill, or other feature), we converted these features to polygons with at least a 100-meter buffer. In general, if the polygon extended beyond the coastline (e.g., Java), coastal areas were cropped to coastlines from the OSM data (OSM tag ‘natural = coastlines’). Finally, all polygons were simplified using the QGIS native Simplify tool with the Visvalingam algorithm and a threshold tolerance set of 100. This resulted in the removal of redundant polygon vertices, so the resulting dataset saved data storage space, with negligible loss of information. The resulting polygons were stored in a GeoPackage file that was published as part of the dataset repository. In addition, the polygons were written into the dataset itself as well-known text (WKT). This allows users to check the individual areas from which the coordinates were created, and to make further edits and updates.

We assigned a country name and code to every record based on ISO 3166-1 alpha-2. To obtain coordinates and positional uncertainty from polygon geometries, we computed enclosing circles and their centroids. If such a centroid was outside the original polygon geometry, we calculated the nearest point that intersecting the polygon. We then calculated the geodetic distance from that point to the most distant point on the polygon (i.e., the radius). These points represent the coordinates of the record, and the distances represent the positional uncertainties. These values were calculated in R 4.3.331 with the packages sf32 and lwgeom33.

Dataset updates

Records in the dataset can be updated by directly editing the ‘zoraptera_occs.csv’ or semiautomatically from iNaturalist and GBIF. The iNaturalist update workflow starts by revising the identification directly in iNaturalist, then we use the rinat R package34 to check new records or identification updates verified by specific users (for the initial version of dataset only Petr Kočárek); compliant data are then automatically appended to the ‘zoraptera_occs.csv’ dataset, and the date of an update is recorded in the log file. The GBIF update workflow starts by downloading the current Zoraptera data from GBIF using the rgbif R package35. On each update, the current GBIF dataset is compared with the last downloaded and revised GBIF dataset based on the gbifID of the records. The date and the dataset doi are stored in a log file to repeat this process. All new GBIF records are temporarily stored and manually revised and implemented in ‘zoraptera_occs.csv’. Polygon geometry can be manually added or edited within the GeoPackage, and the coordinates with positional uncertainties can be automatically recalculated and updated in ‘zoraptera_occs.csv’.

Data Records

The dataset includes additional companion files, all of which are available in the GitHub repository (https://github.com/kalab-oto/zoraptera-occurrence-dataset). When a new version is released, it is automatically transferred to the Zenodo repository, where it is given a DOI identifier that ensures the ability to reference the specific static version of the dataset. The dataset and the entire repository are updated and versioned with an available change history. The Zoraptera Occurrence Dataset 1.1.036 provides information on all 47 taxonomically valid species of Zoraptera distributed in ten genera classified in both currently valid families, Zorotypidae and Spiralizoridae, and contains 656 distribution records dating from 1895 to 2024 (see Table 1, and Figs. 1, 2).

The main file contains a ready-to-use standalone Zoraptera Occurrence Dataset in CSV format, ‘zoraptera_occs.csv’, based on the DarwinCore (DwC) standard37. We used these columns according to DwC: ‘order’, ‘family’, ‘subfamily’, ‘genus’, ‘specificEpithet’ ‘scientificName’, ‘taxonRank’, ‘scientificNameAuthorship’, ‘identificationQualifier’, ‘originalNameUsage’, ‘nomenclaturalStatus’, ‘country’, ‘locality’, ‘verbatimElevation’, ‘verbatimLatitude’, ‘verbatimLongitude’, ‘decimalLatitude’, ‘decimalLongitude’, ‘coordinateUncertaintyInMeters’, ‘habitat’, ‘eventDate’, ‘day’, ‘month’, ‘year’, ‘organismRemarks’, ‘typeStatus’, ‘recordedBy’, ‘identifiedBy’, ‘associatedReferences’, ‘taxonRemarks’, ‘licence‘, ‘georeferenceRemarks’, ‘georeferenceSources’, ‘georeferencedBy’, ‘georeferencedDate’ and ‘footprintWKT’; for more details, see the Darwin Core Quick Reference Guide38. We added the identification ‘zodID’ column and four custom columns regarding geospatial properties or relationships to the data sources: ‘osmID’: id of the related OSM geometry, ‘polygon_fid’: id of the related polygon in ‘geom.gpkg’ file, ‘gbifID’: id of the related GBIF record, and ‘inatID’: id of the related iNaturalist record.

The repository also contains a GeoPackage ‘geom.gpkg’ with polygon geometries of records sites and stored information about its origin in the ‘feature_origin’ attribute with four categories: ‘manual’: not related to any OSM feature, manually digitized from the description; ‘osm_related’: features related to OSM features, not intersecting them but manually digitized based on them (i.e., the polygon manually digitized in a place distant from the OSM feature); ‘osm_derived’: features derived from OSM features, features intersecting each other (i.e., the area around the OSM point or line feature, the edited geometry of the OSM polygon feature); and ‘osm_exact’: features that are exact copies of OSM features (however, they may differ in the final data, owing to postprocessing geometry simplifications). If applicable, to ensure that the OSM source feature is easy to find, raw information from the OSM is stored as ‘osm_id’, ‘class’, and ‘type’.

The non-dataset part of the repository consists of the table ‘taxon_rank.csv’, which summarizes taxon ranks and their authors by the order and is used to complete taxonomic information during updates; the R script ‘geom_calc.r’, which is used to write polygons in WKT and calculate point coordinates of records and their positional uncertainty from ‘geom.gpkg’ polygons; R scripts for updating data from GBIF (‘gbif.r’) and iNaturalist (‘inat.r’), the log file ‘update.log’ for storing information about semi-automatic updates; an R script for creating graphical overviews of the data (‘plots.r’); and the QGIS project ‘zoraptera.qgz’ for reviewing data or adding or editing geometries. Finally, the repository includes a readme file ‘README.md’ that briefly describes the repository and its components.

Technical Validation

The majority of the distribution records included in the dataset are based on studies published in scientific journals, books, and reports typically managed by experts on Zoraptera (e.g., Hubbard, Kočárek, Matsumura, Rafael); therefore, we have confidence in their accuracy. The dataset does not include data that were subsequently found not to be related to Zoraptera based on an additional review. Data on the occurrence of Formosozoros newi Chao & Chen were not included, as the current research has confirmed that this species does not belong to Zoraptera but instead is an unspecified nymph of Dermaptera20. Distribution data of Zoraptera from Uganda39 were not included, as, based on communication with the authors and additional identification according to photographs of the material (P. Kočárek det. 2024), it was found to be not representative of Zoraptera but rather Coleoptera. The species Menonia cochinensis George from India40 was not included, because according to the description and illustrations, it is obviously a nymph of a cricket (Orthoptera: Grylloidea) (see also17).

Records obtained from GBIF have been critically reviewed as, in some cases, such data may be considered uncertain or not corroborated by publications. The public iNaturalist database is only a limited source of Zoraptera occurrence records, as uniform external morphology of Zoraptera usually does not allow the determination of Zoraptera species from photographs or the reliable assignment of records to supraspecific taxonomic categories. Community identification often leads to misidentification in the case of Zoraptera, as determiners assign records to species according to their known geographic distribution. The geographic distribution of Zoraptera is very poorly understood, and there are usually more species distributed in given tropical countries than have been published thus far. In addition, certain iNaturalist records are automatically imported into other databases, such as GBIF, regardless of their misidentification. We strongly discourage the use of Zoraptera data from iNaturalist for purposes other than recording the occurrence of the order, except for well-documented records or records from faunistically well-studied areas. In particular, the level of exploration in the USA allows Zoraptera finds originating from areas outside of the southern parts of Florida to be considered as Usazoros hubbardi (according to the current state of taxonomic knowledge). However, we cannot completely rule out the possibility of a species complex, and a molecular review of U. hubbardi throughout its range will be necessary. All Zoraptera entries in the iNaturalist database were revised by Petr Kočárek directly on the website and used in our dataset with his identification, regardless of the result of the consensus identification by the iNaturalist community. Our update process from iNaturalist (‘inat.r’ script) is configurable to add other iNaturalist users whose identifications will be taken into account.

Each published record in the dataset is associated with a bibliographic reference, iNaturalist id, or GBIF id, allowing users to assess the validity of the record and reuse the data. All the polygon geometries used to calculate the coordinates and uncertainty of the record position are available in the dataset and separate geospatial file. All unpublished records have been identified by the world specialist in the group, P. Kočárek, who guarantees their correctness. As our team has been continuously working on the taxonomy of Zoraptera for many years, we have also included in the dataset currently processed and otherwise unpublished taxa, among which some specimens have not yet been identified to species level and those that have not yet been described taxonomically. The identification status of such records is always indicated, and as soon as the identification is completed or the new species description is published, the record is updated in the dataset. Data from iNaturalist and GBIF are updated and verified regularly.

Providing the occurrence data of Zoraptera to date is a dynamic activity, and the classification and systematics of Zoraptera have often been updated in recent studies. However, we aim to keep the species list and distribution data updated based on our direct research in the literature or based on the research activities of our team, as well as direct contributions from our colleagues, i.e., experts on Zoraptera. The dataset can be updated manually by editing the dataset file directly or semi-automatically from iNaturalist and GBIF. Data will be corrected and updated when errors or updates are reported to the GitHub repository (https://github.com/kalab-oto/zoraptera-occurrence-dataset/issues) or directly to the corresponding senior author (petr.kocarek@osu.cz). We welcome any discussions and contributions from colleagues that could lead to the expansion and improvement of the dataset or its creation workflows.

Usage Notes

The records of the dataset reported here were last updated and carefully manually checked in August 2024 and will be updated periodically in the future. The main dataset file ‘zoraptera_occs.csv’ is a ready-to-use CSV file, which is a common exchange format for tabular text files. This file also contains columns with geographic coordinates and a polygon footprint written in WKT form if applicable. This allows the dataset to be used both as a common table and as a spatial object in GIS software, programming language packages, or libraries capable of working with geospatial data. The repository also includes a standalone GeoPackage file, ‘geom.gpkg’, which contains the source geospatial information for retrieving coordinates and uncertainties in the main dataset file. As an OGC standard, the GeoPackage can be opened in major GIS software, packages, or libraries. If the user needs to use a ‘footprintWKT’ column, be careful when editing the table in the spreadsheet program and check the specifics of the software. Some spreadsheet programs may have a limited number of characters per cell, and because polygons in WKT can be long, the software may truncate values that are too long. If such a file is saved, the WKT geometries may be invalid. In this case, however, the rest of the data is not affected, and ‘footprintWKT’ can be easily restored from the original dataset, or recalculated from ‘geom.gpkg’ using the ‘geom_calc.r’ script.

When working with the dataset, we strongly discourage users from updating the dataset with data from publicly available sources such as iNaturalist or GBIF without critical review. Uncritical work with Zoraptera occurrences in these databases could lead to bias in taxonomic identification and further bias in possible analysis results.

Code availability

The code used to recalculate coordinates and positional uncertainty from polygons and the code used for data updates from iNaturalist and GBIF are part of the dataset’s GitHub repository (https://github.com/kalab-oto/zoraptera-occurrence-dataset) as well as the Zenodo repository36.

References

Mashimo, Y. et al. 100 years Zoraptera—a phantom in insect evolution and the history of its investigation. Insect Syst. Evol. 54(4), 371–393 (2014).

Kočárek, P., Horká, I. & Kundrata, R. Molecular phylogeny and infraordinal classification of Zoraptera (Insecta). Insects 11, 51 (2020).

Kočárek, P. & Horká, I. A new cryptic species of Brazilozoros Kukalova-Peck & Peck, 1993 from French Guiana (Zoraptera, Spiralizoridae). Zoosystema 45, 163–175 (2023).

Kočárek, P. & Horká, I. Cryptic diversity in Zoraptera: Latinozoros barberi (Gurney, 1938) is a complex of at least three species (Zoraptera: Spiralizoridae). PLoS ONE 18, e0280113 (2023).

Matsumura, Y., Maruyama, M., Ntonifor, N. N. & Beutel, R. G. A new species of Zoraptera, Zorotypus komatsui sp. nov. from Cameroon and a redescription of Zorotypus vinsoni Paulian, 1951 (Polyneoptera, Zoraptera). ZooKeys 1178, 39–59 (2023).

Lima, S. P., Oliveira, I. B., Mazariegos, L. A., Fernandes, L. A. & Rafael, J. A. A new species of Centrozoros Kukalová-Peck & Peck, 1993 (Zoraptera: Spiralizoridae) from high elevations in the northwestern Andes of Colombia. Zootaxa 5477, 237–245 (2024).

Matsumura, Y. et al. The evolution of Zoraptera. Syst. Entomol. 45(2), 349–364 (2020).

Beutel, R. G. & Weide, D. Cephalic anatomy of Zorotypus hubbardi (Hexapoda: Zoraptera): New evidence for a relationship with Acercaria. Zoomorphology 124, 121–136 (2005).

Yoshizawa, K. The Zoraptera problem: evidence for Zoraptera + Embiodea from the wing base. Syst. Entomol. 32, 197–204 (2007).

Montagna, M. et al. Recalibration of the insect evolutionary time scale using Monte San Giorgio fossils suggests survival of key lineages through the End-Permian Extinction. Proc. R. Soc. B 286, 20191854 (2019).

Wipfler, B. et al. Evolutionary history of Polyneoptera and its implications for our understanding of early winged insects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116, 3024–3029 (2019).

Chesters, D. The phylogeny of insects in the data‐driven era. Syst. Entomol. 45(3), 540–551 (2020).

Tihelka, E. et al. Compositional phylogenomic modeling resolves the ‘Zoraptera problem’: Zoraptera are sister to all other polyneopteran insects. Preprint at https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.09.23.461539v1.full (2021).

Kočárek, P., Kočárková, I. & Kundrata, R. Morphology of male genitalia and legs reveals the classification of Mesozoic Zoraptera (Insecta). Preprint at: https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.01.08.631689 (2025).

Evangelista, D. A. et al. An integrative phylogenomic approach illuminates the evolutionary history of cockroaches and termites (Blattodea). Proc. R. Soc. B 286, 20182076 (2019).

Choe, J. C. in Insect Biodiversity Vol. 1 (eds Foottit, R. G. & Adler, P. H.) Biodiversity of Zoraptera and their little-known biology. Science and Society, John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Volume 2, pp. 199-217.

Hubbard, M. D. A catalog of the order Zoraptera (Insecta). Insecta Mundi 4, 49–66 (1990).

Engel, M. S. A new Zorotypus from Peru, with notes on related neotropical species (Zoraptera: Zorotypidae). J. Kansas Entomol. Soc. 73, 11–20 (2000).

Rafael, J. A. & Engel, M. S. A new species of Zorotypus from Central Amazonia, Brazil (Zoraptera: Zorotypidae). Am. Mus. Novit. 3528, 1–11 (2006).

Mashimo, Y., Matsumura, Y., Beutel, R. G., Njoroge, L. & Machida, R. A remarkable new species of Zoraptera, Zorotypus asymmetristernum sp. n., from Kenya (Insecta, Zoraptera, Zorotypidae). Zootaxa 4388, 407–416 (2018).

Kočárek, P. & Hu, F.-S. An immature Dermapteran misidentified as an adult Zorapteran: The case of Formosozoros newi Chao & Chen, 2000. Insects 14, 53 (2023).

Kočárek, P. & Kočárková, I. Aspiralizoros gen. nov. for Spiralizoros ceylonicus (Zoraptera: Spiralizoridae), an endemic species overlooked for more than a century. Int. J. Trop. Insect. Sci. 44(5), 2463–2470 (2024).

iNaturalist community Observations of Zoraptera. [21.08.2024]. https://www.inaturalist.org (2024).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.zddyrh (2024).

Wieczorek, J. MaNIS/HerpNET/ORNIS Georeferencing Guidelines. Berkeley, California, USA: University of California, Berkeley, Museum of Vertebrate Zoology. http://georeferencing.org/georefcalculator/docs/GeorefGuide.html (2001).

OpenStreetMap https://www.openstreetmap.org/ (2024).

QGIS Development Team. QGIS Geographic Information System. Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project http://www.qgis.org (2024).

Culos, X. OSM place search. Version 1.4.5. URL: https://github.com/xcaeag/Nominatim-Qgis-Plugin [last accessed: 2024/09/18] (2023).

Zermoglio, P. F., Chapman, A. D., Wieczorek, J. R., Luna, M. C. & Bloom, D. A. Georeferencing Quick Reference Guide. Copenhagen: GBIF Secretariat. https://doi.org/10.35035/e09p-h128 (2020).

OpenTopoMap: Topographic maps from OpenStreetMap. URL: https://opentopomap.org [last accessed: 2024/09/18] (2023).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/ (2024).

Pebesma, E. & Bivand, R. Spatial Data Science: With Applications in R. Chapman and Hall/CRC. https://doi.org/10.1201/9780429459016 (2023).

Pebesma, E. lwgeom: Bindings to Selected ‘liblwgeom’ Functions for Simple Features. R package version 0.2-14, https://github.com/r-spatial/lwgeom (2024).

Barve, V. & Hart, E. rinat: Access ‘iNaturalist’ Data Through APIs. R package version 0.1.9, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rinat (2022).

Chamberlain, S. et al. rgbif: Interface to the Global Biodiversity Information Facility API. R package version 3.7.7, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rgbif (2024).

Kaláb, O. et al. Zoraptera Occurrence Dataset (1.1.0) [Data set]. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14652555 (2025).

Wieczorek, J. et al. Darwin Core: An Evolving Community-Developed Biodiversity Data Standard. PLoS ONE 7, e29715, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0029715 (2012).

Darwin Core Maintenance Group. Darwin Core Quick Reference Guide. Biodiversity Information Standards (TDWG). https://dwc.tdwg.org/terms/ (2021).

Kizito, E. B., Masika, F. B., Masanza, M., Aluana, G. & Barrigossi, J. A. F. Abundance, distribution and effects of temperature and humidity on arthropod fauna in different rice ecosystems in Uganda. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 5, 964–973 (2017).

George, C. J. A new genus and species of Zoraptera. J. Univ. Bombay 4, 86–88 (1936).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Grant Agency of the Czech Republic (project No. 22-05024S; Evolution of angel insects (Zoraptera): from fossils and comparative morphology to cytogenetics and transcriptomes).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

O.K.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing, visualization; J.H.: methodology, investigation, writing - review & editing; G.P.: investigation, writing - review & editing; I.K.: investigation, writing - review & editing; R.K.: conceptualization, investigation, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition; P.K.: conceptualization, methodology, validation, investigation, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kaláb, O., Hoffmannova, J., Packova, G. et al. Curated global occurrence dataset of the insect order Zoraptera. Sci Data 12, 360 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04696-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04696-4