Abstract

The dinoflagellate Scrippsiella acuminata (formerly Scrippsiella trochoidea) is a cosmopolitan species commonly forms dense blooms worldwide. It also has been adopted as representative species for life history studies on dinoflagellates. The peculiar genetic features of its large nuclear genome make the whole-genome sequencing highly challenging. Herein, we employed single-molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing technology to acquire the full-length transcriptome of S. acuminata at different life stages (vegetative cells at different growth stages and resting cysts). A total of 51.44 Gb clean SMRT sequencing reads were generated, which finally yielded 226,117 non-redundant full-length non-chimeric (FLNC) reads. Among them, 78,393 long non-coding RNA (lncRNA), 550 putative transcription factors (TF) members from 19 TF families, 67,212 simple sequence repeats (SSRs), and 116,417 protein coding sequences (CDSs) were identified. This is the first report on full-length transcriptome of Thoracosphaeraceae in Dinophyceae, which is valuable for future genome annotation in this order. Our dataset provides a reference transcriptomic background for life history studies on dinoflagellates and will contribute to understanding molecular mechanisms underlying S. acuminata blooms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Dinoflagellates are an ancient1 and diverse group of unicellular eukaryotes, belonging to the infrakingdom Alveolata that also comprises the phyla Ciliophora and Apicomplexa2. As most important eukaryotic primary producers in the ocean other than diatoms, they are pivotal contributors to primary productivity and food webs of coastal marine ecosystems and involved in global carbon fixation, element cycles, and oxygen production3. Some members in this lineage have drawn great attention owing to their mutualism relationship with other living organisms, such as reef-building corals and invertebrates4. This group also gained increasing attentions due to being the most common causative agents of harmful algal blooms (HABs) worldwide, nearly 200 out of ~2300 dinoflagellate species account for ~75% of HABs events5, ~40% of all HABs-causing species6. Dinoflagellates also include the highest number of toxic species among marine phytoplankton7, which directly poison animals and indirectly threaten human health via consumption of contaminated seafood. The non-toxic dinoflagellate HABs also cause seawater discolorations, oxygen depletion and mucilage duo to high biomass, and thus negatively affect coastal ecosystems and human activities7. Resting cyst is well-known as the dormant stage in the life history of dinoflagellates8,9, which have many structural, functional, and adaptive features analogous to the seeds of higher plants8,10,11,12. Resting cysts play pivotal roles in the biology and ecology of dinoflagellates, particularly in the processes of HABs, as they are associated with genetic recombination, bloom initiation, bloom termination, bloom recurrence, and geographic expansion9,13,14,15. The abundance and distribution of resting cysts in marine sediments have been used to empirically predict the intensity and extent of the forthcoming blooms16,17.

Genome size varies considerably in dinoflagellates (~3–245 Gb)2, which represent 1–80-fold of a human haploid genome and is larger than the largest genomes of animal (lungfish, 130 Gb)18 and plant (Paris japonica, 149 Gb)19. Over half a century of extensive research on dinoflagellate biology reveals that they defy many cytological and genomic characteristics commonly attributed to eukaryotic cell biology and function20, such as high copy numbers of genes (e.g. rRNA gene) in a single cell, high methylated nucleotides, high portion (>35%) of thymine replaced by hydroxumethyluracil, and permanently condensed chromosomes throughout cell cycle21. Genomic approaches to study dinoflagellates are usually restricted by their extremely large nuclear genomes and peculiar genetic features4,20. Until now, available high-quality dinoflagellate genome data are restricted to symbiotic or parasitic species with relatively small genome-sized (0.12–4.8 G bp)4,20,22.

The thecate dinoflagellate Scrippsiella acuminata (formerly S. trochoidea23) is a cosmopolitan species24 that commonly forms dense blooms worldwide and has been shown to cause rapid lethal effects on shellfish (Crassostrea virginica and Mercenaria mercenaria) larvae25. Due to easily produce resting cysts both in laboratory and field, S. acuminata has been adopted as representative species for studies on dinoflagellates life history11,26,27,28,29,30. The RNA-Seq (high-throughput RNA-sequencing) has been employed to unravel the molecular mechanisms underpinning the life stage transitions of S. acuminata with aim to gain insights into how external environmental factors induce resting cysts formation and/or blooms initiation11,26,30. Meanwhile, transcriptomic approach has been extensively used to explore the mechanisms of S. acuminata blooms31,32. However, the fundamental limitation of these work is short read lengths (Table 1), which makes them difficult to accurately capture complete transcripts due to the complex genome structure. The full-length transcriptome sequencing offers a practical avenue and better opportunity to decipher the physiological mechanisms of these non-model but ecologically important species without the reference genome33,34.

In this study, we obtained the full-length transcriptome of S. acuminata at different life stages (vegetative cells at different growth stages and resting cysts) by SMRT sequencing on the Pacific Biosciences Sequel Platform (Fig. 1). Totally, 51.44 Gb of clean SMRT sequencing reads were generated, resulting in 596,485 circular consensus (CCS) reads with an average length of 3,726 bp. Among these, 579,919 (97.2%) were identified as FLNC reads. After clustering, error correction, and redundancy removal, 226,117 (37.9%) non-redundant FLNC reads were obtained, with 130,134 (57.55%) successfully annotated against five public databases. In addition, a total of 116,417 open reading frames (ORFs) with protein coding sequences were identified. Furthermore, a total of 78,393 lncRNAs, 550 putative TF members from 19 TF families, and 67,212 SSRs were identified, respectively. Our work provided the first full-length transcripts set of Thoracosphaeraceae in Dinophyceae, which will contribute to future genome annotation in this order. The dataset is significant for advancing life history studies on dinoflagellates and valuable for elucidating mechanisms of S. acuminata HABs in the coastal environments.

Methods

Algal maintenance

Scrippsiella acuminata (strain IOCAS-St-1) used in this study was originally isolated from the Yellow Sea, China, and maintained in the Marine Biological Culture Collection Centre, Institute of Oceanology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. The culture was maintained in f/2-Si medium35, prepared using pre-filtered (0.22 μm membrane filter; Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) and autoclaved (121 °C for 30 minutes) natural seawater, with a salinity range of 32–33. To prevent bacterial contamination, the medium was supplemented with a penicillin-streptomycin solution (containing 10,000 I.U. of penicillin and 10,000 µg·mL−1 of streptomycin, Solarbio, Beijing, China) to achieve final concentrations of 300 I.U./mL of penicillin and 300 µg·mL−1 of streptomycin after inoculation. The antibiotic solution was added every 7 days throughout the experiment. Cultures were kept in an incubator at 20 ± 1 °C with a 12-hour light/dark cycle, receiving a light intensity of 100 µmol photons m−2·s−1.

Preparation and collection of S. acuminata at different life stages

Three samples were used for library construction: vegetative cells at exponential growth stage, vegetative cells at stationary growth stage and resting cysts. For vegetative cells preparation, three replicate 500 mL flasks, each containing 300 mL of medium, were inoculated with S. acuminata cultures at an initial cell density of approximately 1 × 10³ cells per millilitre under consistent culture maintenance conditions. The experiments lasted 16 days, 0.5 mL of culture sample (3 replicates) was taken every day and fixed with Lugol’s solution (3% final concentration) for enumeration under an inverted microscope using a 1 mL Sedgewick Rafter counting chambers. The growth curve was determined via daily cell counting. The growth stages of vegetative cells were determined according to growth curve (Fig. 2). Vegetative cells at the exponential growth stage (Day 8; the day of inoculation was recorded as Day 0) and stationary growth stage (Day 14) were harvested for further experiments.

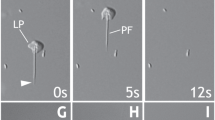

Resting cysts were produced following the method described by Yue et al.36, and briefed as follows. Vegetative cells at the exponential growth stage were cultured in cell culture flasks (Nest, US; 72 cm² cell culture flasks) for resting cyst production. These were incubated under the previously mentioned maintenance conditions, with the addition of f/2-Si medium diluted to one-thousandth of the nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) nutrients36. Resting cysts formation was monitored every day using an inverted microscope (Olympus IX73). There were clear distinctions in morphological features between vegetative cells and resting cysts of S. acuminata (Fig. 3), which allowed a swift judgement via light microscopy between them. Resting cysts were generally collected from cultures that had been inoculated for over 14 days. The obtained resting cysts were washed with sterile filtered seawater until no motile cells (vegetative cells or planozygotes) observed in the samples under microscope. All collected samples (vegetative cells at different growth stages and resting cysts) were concentrated via concentration, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and then stored at −80 °C until RNA extraction.

RNA isolation and library construction

Total RNA was extracted by using RNeasy® Plant Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Germany) and subsequently digested using the RNase-Free DNase Set (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The quality and concentration of the RNA were assessed using 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and quantified with a NanoDrop™ 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The detailed information on cell quantity, RNA quality and quantity for each sample has been provided in Table 2.

For library construction, a total of 12 μg of high-quality RNA from different samples were mixed in equal amounts. The sequencing libraries were then created according to PacBio’s iso-seq sequencing protocol. The initial step involved generating complete cDNA strands by using the NEBNext® Single Cell/Low Input cDNA Synthesis & Amplification Module. This was succeeded by the PCR-based amplification and subsequent purification of the cDNA. The next phase entailed repairing any damage to the cDNA and refining the ends. The concluding stage saw the attachment of SMRT hairpin adapters to the terminal regions of the cDNA duplexes. To verify the quality of the library, evaluations of its purity, concentration, and the size of the inserts were conducted using the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system from Agilent Technologies, based in California, USA. Qualified libraries were then subjected to full-length transcriptome sequencing on the PacBio sequencing platform at BGI Genomics Co. Ltd.

Single-molecule real-time sequencing

The raw sequencing data were processed using SMRT Link v10.0 software. The CCSs were obtained from subreads using the following parameters: min_length = 300, max_length = 15,000, and min passes = 1. Polished CCS subreads were generated using the ccs tool (v6.2.0), applied to the subread BAM files with a minimum quality threshold of 0.9 (-min-rq 0.9). Lima (v2.1.0) and IsoSeq. 3 refine were employed to remove the primers and poly (A) tails, respectively. The FLNCs were recognized by detecting the presence of cDNA ends (3′ and 5′) and poly (A) tail. The clustering algorithm Iterative Clustering for Error Correction (ICE) was used to identify consensus FLNCs (high-quality transcripts, accuracy > 99%). The integrity of the transcriptome data was evaluated by BUSCO (Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs) software (v3.0.2), which is based on OrthoDB database.

The raw data comprising polymerase read sequences was 52.56 Gb, while the output data containing subreads sequences was 51.44 Gb, which includes 15,509,209 reads (Table 3). Following transcript merging, the N50 length was 3,696 bp. A total of 596,485 CCS reads were generated, with a mean insert read length of 3,726 bp. Subsequently, all reads were subsequently classified into 226,177 non-redundant FLNCs. The distribution of sequence length was a vital factor in assessing the quality of library construction, as depicted in Fig. 4a. The BUSCO analysis revealed that 160 out of 303 conserved eukaryotic orthologous genes (52.8%) were identified in the S. acuminata transcriptome, with 113 genes (37.3%) being perfectly matched (Fig. 4b).

Functional annotation of full-length transcriptome

All the FLNCs were annotated by conducting translated nucleotide BLAST (BLASTX) searches against public databases, including the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) non-redundant protein database (NR) database, NCBI non-redundant nucleotide database (NT) database, SwissProt database, Pfam database, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database, and clusters of euKaryotic Orthologous Groups (KOG) database, with a 10−5 E-value cutoff. The GO annotations were performed based on the best BLASTX hit from the NR database using the Blast2GO software (v 2.5.0).

A total of 226,117 non-redundant FLNCs were annotated using the NR, NT, SwissProt, KEGG, KOG, Pfam and GO databases and 130,134 FLNCs, accounting for 57.55% of the total, showed successful BLAST hits against known sequences in at least one of the above databases (Table 4). Most sequence similarities were against the NR database (108,570, 48.01%), followed by the NT database (26,460, 11.70%), the SwissProt database (43,963, 19.44%) and the KEGG database (53,997, 23.88%). The annotation results are summarized in Table 4 and represented in Fig. 5.

In the NR annotation, 34,949 (32.19%) of the homologous FLNCs were aligned to Polarella glacialis, followed by Symbiodinium natans (8,598, 7.92%), Symbiodinium microadriaticum (7,665, 7.06%), and Symbiodinium sp. CCMP2592 (7,274, 6.70%) (Fig. 6). In the KEGG database classification, non-redundant FLNCs were annotated across various functional groups, including cellular processes (2,190, 3.59%), environmental information processing (2,320, 3.80%), genetic information processing (19,420, 31.82%), metabolism (35,487, 58.14%) and organismal systems (1,619, 2.65%) (Fig. 7).

The putative functions of non-redundant FLNCs and their products were identified via searching the annotated genes in GO classifications. A total of 48,908 FLNCs were assigned to at least one of the 3 main GO categories: biological process, cellular component, and molecular function (Fig. 8a). These FLNCs were further classified into functional subcategories: 44,468 participated in 23 biological processes, including “cellular process” (41.40%) and “metabolic process” (36.12%) comprised the largest proportion; 34,048 FLNCs related to 2 cellular components, including “cellular anatomical entity” (88.41%) and “protein-containing complex” (11.59%); 60,701 FLNCs involved in 20 molecular functions, with “catalytic activity” (41.66%) being the most abundant, followed by “binding” (39.39%), “transporter activity” (6.65%), and “transcription regulator activity” (3.67%) (Fig. 8a).

Functional categorization of non-redundant FLNCs based on GO (Gene Ontology) terms and KOG (Clusters of Orthologous Groups) classifications. (a) Distribution of genes across GO functional categories: biological process, cellular component, and molecular function. (b) Classification of genes into KOG functional categories highlighting their roles in cellular and metabolic processes.

The KOG annotation yielded 51,800 putative proteins in 25 categories (Fig. 8b). Among these categories, the cluster for “General function prediction” was the largest group (15,161, 29.27%), followed by “Signal transduction mechanisms” (14,605, 28.19%), and “RNA processing and modification” (13,565, 26.19%). Clusters for “Cellmotility” (208, 0.40%), “Nucleotide transport and metabolism” (671, 1.30%), and “Coenzyme transport and metabolism” (731, 1.41%) were the smallest 3 groups (Fig. 8b).

Structure analysis of simple sequence repeats (SSRs)

The SSRs within the full-length transcriptome was identified by using the microsatellite identification tool (MISA v1.0). The FLNCs exceeding 500 bp were screened and used for analysis.

A total of 226,117 non-redundant FLNCs with a total length of 149,572,208 bp were used for SSR prediction. The number of SSRs included mononucleotide repeats (42,038, 62.55%), dinucleotide repeats (5,174, 7.70%), tri-nucleotide repeats (17,724, 26.37%), tetra-nucleotide repeats (435, 0.65%), hexa-nucleotide repeats (1,000, 1.49%) and penta-nucleotide repeats (841, 1.25%) (Fig. 9).

Prediction of protein coding sequences (CDS), transcription factors (TFs), and long non-coding RNA (lncRNAs)

The TransDecode software (v3.0.1) was employed to predict CDS and their corresponding amino acid sequences in FLNCs. The prediction criteria included ORF length, log-likelihood score, and alignment against the Pfam protein domain database. The iTAK software was used for TFs prediction with PlantTFBD as a reference database. Four programs, including Coding Potential Calculator (CPC)37, Coding-Non-Coding-Index (CNCI)38, predictor of long non-coding RNAs and messenger RNAs based on an improved k-mer scheme (PLEK)39, and Pfam40 database were used to predict lncRNAs within the full-length transcriptome.

In total, 116,417 coding sequences were predicted using TransDecoder, with the total length of 75,895,596 bp. A total number of 550 putative TF members were obtained and categorized into 19 families. The top 11 TF families were as follows: Cysteine and Serine-rich Domain (CSD) with 213 members; C3H-type Zinc Finger (C3H) with 178 members; Forkhead-associated domain (FHA) with 69 members; Apetala2/Ethylene-responsive element-binding protein (AP2-EREBP) with 19 members; Myeloblastosis (MYB) with 14 members, MYB-related with 14 members; C2H2 Zinc Finger (C2H2) with 10 members; Tubulin (TUB) with 9 members; Lin-11, Isl-1, and Mec-3 (LIM) with 4 members; Bromodomain and SAMP domain-containing (BSD) with 4 members; and Bending-Binding Receptor (BBR)/BPC with 4 members (Fig. 10).

LncRNAs were predicted using four methods including CPC, CNCI, PLEK and Pfam structural domain analysis. The common non-coding hits/intersection of the four results were then filtered and considered as lncRNA. We obtained 166,855, 85235, 139,800 and 188,205 putative lncRNAs determined using CPC, CNCI, PLEK and Pfam database, respectively, and among these 78,393 (38.86%) were identified in all analyses (Fig. 11).

Data Records

The dataset is available in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under BioProject accession number PRJNA112775341.

Technical Validation

Obtaining high-quality RNA is a critical prerequisite for the success of full-length transcriptome sequencing. To validate the precision of the sequencing data, we conducted a thorough examination of the RNA samples. This process encompassed the evaluation of sample purity and concentration using the Nanodrop, and the integrity assessment was conducted through the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system.

Code availability

All commands and pipelines used in data processing were executed according to the manual and protocols of the corresponding bioinformatics software. The version and code/parameters of software have been described in Methods. No custom code was used for the curation and/or validation of the dataset in this study.

References

Fensome, R. A. et al. The early Mesozoic radiation of dinoflagellates. Paleobiology 22, 329–338 (1996).

Lin, S. Genomic understanding of dinoflagellates. Res. Microbiol. 162, 551–569 (2011).

Taylor, F. J. R. et al. Dinoflagellate diversity and distribution. Biodivers. Conserv. 17, 407–418 (2008).

Lin, S. et al. The Symbiodinium kawagutii genome illuminates dinoflagellate gene expression and coral symbiosis. Science 350, 691–694 (2015).

Smayda, T. J. Reflections on the ballast water dispersal—harmful algal bloom paradigm. Harmful Algae 6, 601–622 (2007).

Jeong, H. J. et al. Feeding diverse prey as an excellent strategy of mixotrophic dinoflagellates for global dominance. Sci. Adv. 7, eabe4214 (2021).

Hallegraeff, G. M. et al. Perceived global increase in algal blooms is attributable to intensified monitoring and emerging bloom impacts. Commun. Earth Environ. 2, 1–10 (2021).

Tang, Y. Z. et al. Exploration of resting cysts (stages) and their relevance for possibly HABs-causing species in China. Harmful Algae 107, 102050 (2021).

Bravo, I. & Figueroa, R. I. Towards an ecological understanding of dinoflagellate cyst functions. Microorganisms 2, 11–32 (2014).

Bewley, J. D. et al. Seeds: Physiology of Development, Germination and Dormancy 3rd edn (Springer: New York, Heidelberg, Dordrecht, London, 2013).

Deng, Y. et al. Transcriptomic analyses of Scrippsiella trochoidea reveals processes regulating encystment and dormancy in the life cycle of a dinoflagellate, with a particular attention to the role of abscisic acid. Front. Microbiol. 8, 2450 (2017).

Ellegaard, M. & Ribeiro, S. The long‐term persistence of phytoplankton resting stages in aquatic ‘seed banks’. Biol. Rev. 93, 166–183 (2018).

Dale, B. Dinoflagellate resting cysts: “Benthic plankton”, in Survival Strategies of the Algae (ed. Fryxell, G. A.) 69–136 (Cambridge Univ. Press,1983).

Tang, Y. Z. et al. Characteristic life history (resting cyst) provides a mechanism for recurrence and geographic expansion of harmful algal blooms of dinoflagellates: a review. Stud. Mar. Sin. 51, 132–154 (2016).

Anderson, D. M. et al. Evidence for massive and recurrent toxic blooms of Alexandrium catenella in the Alaskan Arctic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118(41), e2107387118 (2021).

Hu, Z. et al. The notorious harmful algal blooms-forming dinoflagellate Prorocentrum donghaiense produces sexual resting cysts, which widely distribute along the coastal marine sediment of China. Front. Mar. Sci. 9, 826736 (2022).

Wang, Z. et al. Distribution of dinoflagellate cysts in surface sediments from the Qingdao coast, the Yellow Sea, China: the potential risk of harmful algal blooms. Front. Mar. Sci. 9, 910327 (2022).

Metcalfe, C. J. et al. Evolution of the australian lungfish (Neoceratodus forsteri) genome: a major role for CR1 and L2 LINE elements. Mol. Biol. Evol. 29, 3529–3539 (2012).

Ruvindy, R. et al. Genomic copy number variability at the genus, species and population levels impacts in situ ecological analyses of dinoflagellates and harmful algal blooms. ISME Commun. 3, 70 (2023).

Aranda, M. et al. Genomes of coral dinoflagellate symbionts highlight evolutionary adaptations conducive to a symbiotic lifestyle. Sci. Rep. 6, 39734 (2016).

Liu, Y. et al. Dependence of genome size and copy number of rRNA gene on cell volume in dinoflagellates. Harmful Algae 109, 102108 (2021).

Stephens, T. G. et al. Genomes of the dinoflagellate Polarella glacialis encode tandemly repeated single-exon genes with adaptive functions. BMC Biol. 18, 56 (2020).

Kretschmann, J. et al. Taxonomic clarification of the dinophyte Peridinium acuminatum Ehrenb., ≡ Scrippsiella acuminata, comb. nov. (Thoracosphaeraceae, Peridiniales). Phytotaxa 220, 239–256 (2015).

Steidinger, K. A. & Tangen, K. Dinoflagellates. In Identifying Marine Diatoms and Dinoflagellates (ed. Tomas, C. R.) 387–589 (Academic Press, San Diego, 1997).

Tang, Y. Z. & Gobler, C. J. Lethal effects of Northwest Atlantic Ocean isolates of the dinoflagellate, Scrippsiella trochoidea, on Eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica) and Northern quahog (Mercenaria mercenaria) larvae. Mar. Biol. 159, 199–210 (2012).

Guo, X. et al. Transcriptome and metabolome analyses of cold and darkness-induced pellicle cysts of Scrippsiella trochoidea. BMC Genomics 22, 526 (2021).

Deng, Y. et al. Molecular cloning of heat shock protein 60 (Hsp60) and 10 (Hsp10) genes from the cosmopolitan and harmful dinoflagellate Scrippsiella trochoidea and their differential transcriptions responding to temperature stress and alteration of life cycle. Mar. Biol. 166, 7 (2018).

Li, F. et al. Probing the energetic metabolism of resting cysts under different conditions from molecular and physiological perspectives in the harmful algal blooms-forming dinoflagellate Scrippsiella trochoidea. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 7325 (2021).

Li, F. et al. Characterizing the status of energetic metabolism of dinoflagellate resting cysts under mock conditions of marine sediments via physiological and transcriptional measurements. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 15033 (2022).

Wu, X. et al. Energy metabolism and genetic information processing mark major transitions in the life history of Scrippsiella acuminata (Dinophyceae). Harmful Algae 116, 102248 (2022).

Cooper, J. T. et al. Transcriptome Analysis of Scrippsiella trochoidea CCMP 3099 Reveals Physiological Changes Related to Nitrate Depletion. Front. Microbiol. 7, 639 (2016).

Sirius, P. K. & Lo, S. C. Comparative proteomic studies of a Scrippsiella acuminata bloom with its laboratory-grown culture using a 15N-metabolic labeling approach. Harmful algae 67, 26–35 (2017).

Pan, X. et al. Full-length transcriptome analysis of a bloom-forming dinoflagellate Prorocentrum shikokuense (Dinophyceae). Sci. Data 11, 430 (2024).

Ji, N. et al. Full-Length Transcriptome analysis of the ichthyotoxic harmful alga Heterosigma akashiwo (Raphidophyceae) using single-molecule real-time sequencing. Microorganisms 11, 389 (2023).

Guillard, R. R. L. Culture of phytoplankton for feeding marine invertebrates. in Culture of marine invertebrate animals: Proceedings—1st Conference on Culture of Marine Invertebrate Animals Greenport (eds. Smith, W. L. & Chanley, M. H.) 29–60 (Springer US, Boston, MA, 1975).

Yue, C. et al. Deficiency of nitrogen but not phosphorus triggers the life cycle transition of the dinoflagellate Scrippsiella acuminata from vegetative growth to resting cyst formation. Harmful Algae 118, 102312 (2022).

Kong, L. et al. CPC: assess the protein-coding potential of transcripts using sequence features and support vector machine. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W345–W349 (2007).

Sun, L. et al. Utilizing sequence intrinsic composition to classify protein-coding and long non-coding transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, e166 (2013).

Li, A. et al. PLEK: a tool for predicting long non-coding RNAs and messenger RNAs based on an improved k-mer scheme. BMC bioinformatics 15, 1–10 (2014).

Finn, R. D. et al. The Pfam protein families database: towards a more sustainable future. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D279–D285 (2016).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP516046 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This research was financially supported by the National Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42176207, 42406214), and the Qingdao Postdoctoral Applied Research Project (No. QDBSH20220202137).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Fengting Li carried out the study and drafted the manuscript; Caixia Yue participated the data processing; Yunyan Deng and Ying Zhong Tang directed the project, discussed and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, F., Yue, C., Deng, Y. et al. Full-length transcriptome analysis of a bloom-forming dinoflagellate Scrippsiella acuminata (Dinophyceae). Sci Data 12, 352 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04699-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04699-1