Abstract

Prunus mahaleb is widely utilized as rootstock for cherries in Central Asia due to its exceptional resistance to environmental stressors. In this study, we generated a haplotype-resolved, chromosome-scale genome assembly for P. mahaleb using PacBio HiFi long reads and Hi-C technology. The resulting assembly comprises two haplotypes with sizes of 272.64 Mb (contig N50 = 26.60 Mb) and 271.76 Mb (contig N50 = 30.26 Mb), respectively. We identified 27,965 protein-coding genes (27,627 functionally annotated) and 27,931 protein-coding genes (27,607 functionally annotated) in the two haplotypes, respectively. Additionally, we annotated 145.64 Mb repetitive elements, 2,263 rRNAs, 430 tRNAs, and 780 other non-coding RNAs in haplotype A, and 144.04 Mb repetitive elements, 1,999 rRNAs, 442 tRNAs, and 734 other non-coding RNAs in haplotype B. Further analysis indicated that these haplotypes diverged approximately 2.67 million years ago. This high-quality genome assembly lays a solid groundwork for future initiatives in molecular breeding and functional genomics research for P. mahaleb.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

The genus Prunus (family Rosaceae) encompasses a diverse array of species that are of significant economic and ornamental value, including well-known fruit trees such as apricot (P. armeniaca), peach (P. persica), plum (P. domestica), and cherry (P. avium and P. cerasus)1. Among these, cherries, classified under the subgenus Cerasus, hold a unique position within this genus due to their worldwide appreciation and extensive cultivation. Cherries are prized for their dual role in both aesthetic and nutritional contexts2,3. Beyond their visual appeal, cherries are rich in many nutrients and beneficial to human health4,5. People’s pursuit of cherries has forced the cherry industry to gradually expand.

P. mahaleb, despite its small fruit size, exhibits remarkable resistance to cold, drought and salt, making it a commonly used rootstock for other cherry cultivars in Central Asia, US, European, and China6,7,8. As the global climate continues to change9, with increasing temperatures and unpredic weather patterns, these rootstock with excellent resistance can help plants to grow normally and maintain stable fruit production. Therefore rootstock resistance will become more important10. Despite the inherent advantages of P. mahaleb, traditional breeding programs have made limited progress in further improving its rootstock traits. However, recent technological advancements in genomics are beginning to change this scenario.

The advancement of high-quality genome assemblies has significantly accelerated progress in plant breeding, offering new tools for the molecular design of rootstocks11. By leveraging genomic information, researchers can identify and select desirable traits with greater precision and speed. For example, in other rootstocks such as apples and pears12,13, high-quality genome assemblies have successfully pinpointed key genes responsible for dwarfing and early fruiting traits from rootstocks. Among the common rootstocks of cherry, only the genome of the P. fruticosa has been published, but it is at the contig level with relatively high fragmentation14. This has hindered progress in rootstock breeding, underscoring the urgent need for high-quality genomes to support the development of superior rootstocks. Moreover, P. mahaleb represents the basal taxon of the subgenus Cerasus15. Annotating the genome of P. mahaleb will provide deeper insights into the evolutionary history of cherry species. Understanding the genetic underpinnings of this basal species could shed light on the evolutionary processes that have shaped the diversity within the subgenus Cerasus, offering a broader perspective on the relationships and adaptations among cherry species.

In this study, we employed PacBio high-fidelity (HiFi) sequencing combined with high-throughput chromosome conformation capture (Hi-C) to assemble and annotate the chromosome-level, haplotype-resolved genome of P. mahaleb. We successfully anchored the assembled allele sequences to 16 pseudochromosomes, consistent with the species’ karyotype (2n = 16)16 (Fig. 1). The assembled genome was then finally divided into two haplotypes based on repetitive kmers: haplotype A (272.64 Mb) and haplotype B (271.76 Mb) (Table 1). The quality and completeness of the genome assembly were rigorously assessed using Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO, v5.4.7)17. The analysis demonstrated a high level of completeness, with 98.0% of the haplotype A genome and 98.1% of the haplotype B genome identified as complete. These results confirm the high quality of the assembled genomes for both haplotypes. Gene annotation identified 27,965 protein-coding genes in the haplotype A genome and 27,931 protein-coding genes in the haplotype B genome (Table 2). Additionally, a total of 289.68 Mb (~53.21%) of repetitive sequences were characterized, including 145.64 Mb (~53.42%) in haplotype A and 144.04 Mb (~53.00%) in haplotype B (Table 3). Furthermore, the annotation process revealed a total of 6,648 non-coding RNA (ncRNA) genes, including 4,262 rRNA genes (2,263 in haplotype A and 1,999 in haplotype B), 872 tRNA genes (430 in haplotype A and 442 in haplotype B), and 1,514 other ncRNA genes (780 in haplotype A and 734 in haplotype B) (Table 4).

The landscape of genome assembly and annotation of Prunus mahaleb. Each track is represented within a 50 kb window. Tracks from outer to inner represent: (a) Chromosomes of P. mahaleb; (b) GC content; (c) gene density; (d) Transposable element (TE) density; and. (e) Non-coding RNA density. In the heatmap, red represents a high percentage, while blue indicates a low percentage.

We hope this high-quality, haplotype-resolved genome assembly will make a significantly contribution to improving P. mahaleb rootstock traits, accelerating the molecular breeding process, and enhancing our understanding of the evolutionary history of the subgenus Cerasus.

Methods

Sample preparation and genomic sequencing

All the samples were collected from the same P. mahaleb cultivated at the Shanghai Chenshan Botanical Garden (31°4′25″N, 121°10′40″E). Fresh young leaves were collected from selected individuals for genome sequencing. For transcriptome RNA extraction, samples of young leaves, current-year branches, and flowers were also gathered. To ensure preservation, all samples were rapidly flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately after collection and stored at −80 °C.

All library preparation and sequencing were performed by Xi’An Haorui Gene Technologies Ltd (Xi’an, China), following the protocols outlined below.

For PacBio long-read sequencing, genomic DNA was extracted using a modified Cetyltrimethylammonium Bromide (CTAB) method18. The fragmented DNA was purified with AMPure PB magnetic beads, and a HiFi library was constructed using the SMRTbell prep kit 3.0 (PacBio, USA). Sequencing was carried out on the PacBio Revio platform (PacBio, USA), yielding 29.47 Gb of circular consensus sequencing (ccs) reads, corresponding to approximately 54.1 × coverage (Table 5).

The Hi-C library preparation involved fixing fresh P. mahaleb young leaves in 2% formaldehyde19. The fixed tissues were homogenized and centrifuged to isolate nuclei. The cross-linked chromatin was digested with DpnII, labeled with biotin, and ligated with T4 DNA ligase. After de-crosslinking, the DNA was purified and fragmented into 300–500 bp segments. Fragments containing interaction sites were enriched using streptavidin magnetic beads to construct the Hi-C library. High-throughput sequencing on the DNBSEQ-T7 platform (BGI, China) produced 39.37 Gb of Hi-C reads, equating to approximately 72.3 × coverage (Table 5).

For transcriptome sequencing, RNA was extracted from plant tissues using the DP411 and DP762-T1C kits (TIANGEN, China). mRNA was subsequently purified using the Dynabeads mRNA Purification Kit (Invitrogen, USA). RNA libraries were prepared and sequenced on the DNBSEQ-T7 platform (BGI, China), resulting in 29.8 Gb of RNAseq reads, which were utilized for the genome annotation (Table 5).

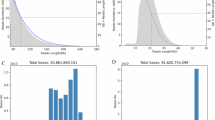

Genome assembly

PacBio HiFi reads and Hi-C short reads were combined in Hifiasm v0.19.720, employing the Hi-C Integrated Assembly mode to generate contigs for two distinct haplotypes. Subsequently, the Hi-C reads were simultaneously compared to the merged contigs for scaffolding using the Haphic pipeline21 with the argument–remove_allelic_links 2. The resulting data was then converted to yahs-compatible Hi-C format. Manual corrections were applied using Juicebox v1.11.0822 to rectify misinsertions and optimize contig orientations, thereby ensuring the overall chromosome structure. The corrected chromosomes were then typed using Subphaser23 with parameters set to -k 755 -q 2 -f 2.0, resulting in the final identification of haplotype A and haplotype B (Fig. 2). The specific k-mers were mapped to the two haplotype genomes to generate their distribution patterns. Additionally, the assembled genomes were characterized for telomeres and centromeres using quartet24 (Fig. 3).

Telomere detection map. Triangles and boxes denote the positions of telomeres and gaps within the assembled chromosomes of P. mahaleb. The central constriction marks the location of the centromere. Regions with high density of specific kmer are shown in red, while those with low density are displayed in blue.

Repeat annotation

The de novo identification of transposable elements (TEs) was performed using the EDTA (Extensive de novo TE Annotator) pipeline v2.1.025, with the parameters--sensitive 1--anno 1. A total of 145.64 Mb (53.42%) of assembled sequences were annotated as TE in haplotype A, including LTR (27.29%), TIR (24.98%) and Helitron (1.15%). In contrast, a total of 144.04 Mb (53.00%) of the assembled sequences in haplotype B were annotated as TE, including LTR (27.18%), TIR (24.66%) and Helitron (1.16%) (Table 3).

Gene structure prediction and functional annotations

Gene structure prediction was carried out using a combination of ab initio and transcriptome-based approaches. RNA-Seq data were processed to obtain transcripts using the Hisat2-StringTie pipeline26,27, with transcript structure validation conducted via the PASA pipeline28. Additionally, Helixer29 was employed for de novo gene annotation, and the predicted gene structures were further validated through PASA to ensure accuracy. Combining the above steps, 27,965 and 27,931 protein-coding genes were finally annotated in haplotype A and haplotype B, respectively (Table 2).

The functional annotation of protein-coding genes was accomplished through a comprehensive three-step approach. Initially, gene sequences were aligned to the eggNOG 5.0.2 database using eggNOG-mapper v2.1.1230, which successfully annotated 87.74% of the genes. Among these, 47.59% were annotated with Gene Ontology (GO) terms (http://geneontology.org/), and 45.14% were linked to pathways from the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) (https://www.genome.jp/kegg). In the second step, BLAST 2.14.1 +31 was utilized to compare gene sequences against three major protein databases: Swiss-Prot (72.34%), TrEMBL (98.63%), and Nr (98.68%), annotating 98.70% of the genes. Finally, InterProScan v5.69-101.032 was employed to functionally characterize 84.57% of the genes across 16 additional databases (Table 6).

Annotation of non-coding RNAs

Non-coding RNAs were identified using Infernal v1.1.533 by querying against the Rfam v14.10 database with default parameters. In haplotype A, the analysis identified 2,263 rRNAs, 430 tRNAs, and 780 other ncRNAs. In haplotype B, 1,999 rRNAs, 442 tRNAs, and 734 other ncRNAs were identified (Table 4).

Comparison between haplotype assemblies

SyRI (Synteny and Rearrangement Identifier) v1.6.334 was employed to detect synteny and structural variations (≥50 bp) and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and small insertions and deletions (InDels) (<50 bp) between the two haplotypes using default parameters. The analysis identified a total of 405 syntenic regions (~226 Mb), 37 inversions (~5 Mb), 1,897 translocations (~3 Mb), 422 duplications in haplotype A (~2 Mb), and 1,734 duplications in haplotype B (~3 Mb). Notably, large inversion segments were observed on chromosomes 2 and 4 (Fig. 4). The analysis revealed 696,916 SNPs (~0.6 Mb), 45,160 insertions (~2 Mb), and 45,434 deletions (~2 Mb). The heterozygosity of P. mahaleb genome is about 2.3%.

Structural variation (SV) distribution between the haplotypes. The horizontal blue lines represent the chromosomes of hapA used as the reference, while the red lines correspond to the chromosomes of hapB. Syntenic regions are shown in grey, inverted regions in orange, duplicated regions in light blue, and translocated regions in green.

LTR insertion times

The LTR sequences of the two haplotypes were identified using annotation results from EDTA, and the nucleotide substitution rate was determined to be 8.09 × 10−9. The results were visualized using R (Fig. 5).

Phylogenetic analyses

Six published genomes2,14,35,36,37,38 closely related to P. mahaleb were selected for clustering orthologous using OrthoFinder v2.5.539 with the parameters ‘-S diamond -M msa -A mafft -T raxml’. Finally, a total of 27,593 orthologous were identified, including 10,802 core orthologous shared among the genomes, comprising 138,986 genes (Fig. 6a). Additionally, 4,093 single-copy genes were identified across these genomes. We performed divergence time estimation using Bayesian Evolutionary Analysis Sampling Tree (BEAST) v2.7.740 and set it as a subcalibration based on two reported divergence times in TimeTree41 (http://www.timetree.org/): ancestral nodes of P. persica and the subgenus Cerasus (adjusted time: 47.0 million years ago [MYA]); P. avium and P. cerasus diverged (adjusted time: 43.0 MYA). A Markov chain Monte Carlo was run for 200,000,000 generations at 1,000 steps per generation. Two haplotypes of P. mahaleb diverged about 2.67 MYA (Fig. 6b).

Genome evolution of P. mahaleb. (a) The orthogroups between the genomes of two haplotypes of P. mahaleb and the rest of the close relatives. pat: P. avium; pcmA: P. cerasus hapA; pcmA′: P. cerasus hapA′; pcmB: P. cerasus hapB; pcon: P. conradinae; pcw: P. campanulate; pmA: P. mahaleb hapA; pmB: P. mahaleb hapB; ppc: P. persica; psw: P. serrulate. (b) Divergence times of ten Prunus genomics. Numbers in red indicate the median divergence time of the two haplotypes of P. mahaleb. Bars on the nodes indicated 95% confidence intervals of estimated times. The unit is in million years ago.

Data Records

The raw sequence data reported in this paper have been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive in National Genomics Data Center (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa) with the accession number CRA01936842, under the project identifier PRJCA030734. Genome assembly at the chromosome level of P. mahaleb has been uploaded to the CNCB Genome Warehouse (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gwh/) under the accession number GWHFFNM00000000.143. Genome annotation files can be downloaded at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.2785406144. The assembly and annotation have been deposited at GenBank under the accession number GCA_048569315.145 and GCA_048569335.146.

Technical Validation

The concentration and size of the inserted fragments were measured using Qubit 2.0 (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) and Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, USA), respectively, while the library’s effective concentration was accurately quantified using qPCR to ensure quality.

The quality of the genome assembly was evaluated using several metrics, including BUSCO with the eudicots_odb10 dataset and consensus quality value (QV)47. The results indicated that 97.8% of the complete core genes, encompassing both single-copy and duplicated genes, were present in the assembled genome (Table 7). For the two haplotypes, the proportions of complete core genes were 98.0% and 98.1%, respectively. The QV of the assembled genome was approximately 69.18, with a k-mer completeness of 99.17% (Table 7).

Code availability

All software utilized in this study was executed in accordance with the official documentation. The specific versions and parameters of the software, along with any custom codes employed, are detailed in the Methods section. Any procedures not explicitly outlined in the Methods were conducted using default parameters.

References

Chin, S.-W., Shaw, J., Haberle, R., Wen, J. & Potter, D. Diversification of almonds, peaches, plums and cherries – Molecular systematics and biogeographic history of Prunus (Rosaceae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 76, 34–48 (2014).

Cao, J. et al. Physicochemical characterisation of four cherry species (Prunus spp.) grown in China. Food Chem. 173, 855–863 (2015).

Cho, M.-S. & Kim, S.-C. Multiple lines of evidence for independent origin of wild and cultivated flowering cherry (Prunus yedoensis). Front. Plant Sci. 10 (2019).

Yoo, K. M., Al-Farsi, M., Lee, H., Yoon, H. & Lee, C. Y. Antiproliferative effects of cherry juice and wine in Chinese hamster lung fibroblast cells and their phenolic constituents and antioxidant activities. Food Chem. 123, 734–740 (2010).

Zhou, Z., Nair, M. G. & Claycombe, K. J. Synergistic inhibition of interleukin-6 production in adipose stem cells by tart cherry anthocyanins and atorvastatin. Phytomedicine 19, 878–881 (2012).

Hrotkó, K. Potentials in Prunus mahaleb L. for cherry rootstock breeding. Sci. Hortic. 205, 70–78 (2016).

Hrotkó, K., Németh-Csigai, K., Magyar, L. & Ficzek, G. Growth and productivity of sweet cherry varieties on hungarian clonal Prunus mahaleb (L.) rootstocks. Horticulturae 9, 198 (2023).

Benny, J. et al. Gaining insight into exclusive and common transcriptomic features linked to drought and salinity responses across fruit tree crops. Plants 9, 1059 (2020).

Li, Q. et al. Different climate response persistence causes warming trend unevenness at continental scales. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 343–349 (2022).

Martins, V. et al. Rootstock affects the fruit quality of ‘Early Bigi’ sweet cherries. Foods 10, 2317 (2021).

Noble, D. W. A., Radersma, R. & Uller, T. Plastic responses to novel environments are biased towards phenotype dimensions with high additive genetic variation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116, 13452–13461 (2019).

Ou, C. et al. A de novo genome assembly of the dwarfing pear rootstock Zhongai 1. Sci. Data 6, 281 (2019).

Li, W. et al. Near-gapless and haplotype-resolved apple genomes provide insights into the genetic basis of rootstock-induced dwarfing. Nat. Genet. 56, 505–516 (2024).

Goeckeritz, C. Z. et al. Genome of tetraploid sour cherry (Prunus cerasus L.) ‘Montmorency’ identifies three distinct ancestral Prunus genomes. Hortic. Res. 10, uhad097 (2023).

Song, Y.-F. et al. Molecular phylogenetics and biogeography reveal the origin of cherries (Prunus subg. Cerasus, Rosaceae). Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 204, 304–315 (2024).

Rice, A. et al. The Chromosome Counts Database (CCDB) – a community resource of plant chromosome numbers. New Phytol. 206, 19–26 (2015).

Manni, M., Berkeley, M. R., Seppey, M., Simão, F. A. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO update: novel and streamlined workflows along with broader and deeper phylogenetic coverage for scoring of eukaryotic, prokaryotic, and viral genomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 4647–4654 (2021).

Doyle, J. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem Bull 19, 11–15 (1987).

Berkum, N. L. van, et al. Hi-C: a method to study the three-dimensional architecture of genomes. J. Vis. Exp. JoVE e55617 https://doi.org/10.3791/1869 (2010).

Cheng, H. et al. Haplotype-resolved assembly of diploid genomes without parental data. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 1332–1335 (2022).

Zeng, X. et al. Chromosome-level scaffolding of haplotype-resolved assemblies using Hi-C data without reference genomes. Nat. Plants 10, 1184–1200 (2024).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicebox provides a visualization system for Hi-C contact maps with unlimited zoom. Cell Syst. 3, 99–101 (2016).

Jia, K.-H. et al. SubPhaser: a robust allopolyploid subgenome phasing method based on subgenome-specific k-mers. New Phytol. 235, 801–809 (2022).

Lin, Y. et al. quarTeT: a telomere-to-telomere toolkit for gap-free genome assembly and centromeric repeat identification. Hortic. Res. 10, uhad127 (2023).

Ou, S. et al. Benchmarking transposable element annotation methods for creation of a streamlined, comprehensive pipeline. Genome Biol. 20, 275 (2019).

Kim, D., Paggi, J. M., Park, C., Bennett, C. & Salzberg, S. L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 907–915 (2019).

Shumate, A., Wong, B., Pertea, G. & Pertea, M. Improved transcriptome assembly using a hybrid of long and short reads with StringTie. PLOS Comput. Biol. 18, e1009730 (2022).

Haas, B. J. et al. Improving the Arabidopsis genome annotation using maximal transcript alignment assemblies. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 5654–5666 (2003).

Stiehler, F. et al. Helixer: Cross-species gene annotation of large eukaryotic genomes using deep learning. Bioinformatics 36, 5291–5298 (2020)

Cantalapiedra, C. P., Hernández-Plaza, A., Letunic, I., Bork, P. & Huerta-Cepas, J. eggNOG-mapper v2: Functional Annotation, Orthology Assignments, and Domain Prediction at the Metagenomic Scale. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 5825–5829 (2021).

Camacho, C. et al. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 10, 421 (2009).

Jones, P. et al. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics 30, 1236–1240 (2014).

Nawrocki, E. P., Kolbe, D. L. & Eddy, S. R. Infernal 1.0: inference of RNA alignments. Bioinformatics 25, 1335–1337 (2009).

Goel, M., Sun, H., Jiao, W.-B. & Schneeberger, K. SyRI: finding genomic rearrangements and local sequence differences from whole-genome assemblies. Genome Biol. 20, 277 (2019).

Wang, J. et al. Chromosome-scale genome assembly of sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.) cv. Tieton obtained using long-read and Hi-C sequencing. Hortic. Res. 7, 122 (2020).

Yi, X.-G. et al. The genome of Chinese flowering cherry (Cerasus serrulata) provides new insights into Cerasus species. Hortic. Res. 7, 165 (2020).

Hu, Y., Feng, C., Wu, B. & Kang, M. A chromosome-scale assembly of the early-flowering Prunus campanulata and comparative genomics of cherries. Sci. Data 10, 920 (2023).

Jiu, S. et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly provides insights into the genetic diversity, evolution, and flower development of Prunus conradinae. Mol. Hortic. 4, 25 (2024).

Emms, D. M. & Kelly, S. OrthoFinder: phylogenetic orthology inference for comparative genomics. Genome Biol. 20, 238 (2019).

Suchard, M. A. et al. Bayesian phylogenetic and phylodynamic data integration using BEAST 1.10. Virus Evol. 4, vey016 (2018).

Kumar, S., Stecher, G., Suleski, M. & Hedges, S. B. TimeTree: a resource for timelines, timetrees, and divergence times. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34, 1812–1819 (2017).

CNCB Genome Sequence Archive https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/browse/CRA019368 (2025).

CNCB Genome Warehouse https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gwh/Assembly/86154/show (2025).

Fu, C. et al. Prunus_mahaleb.anno.gff3. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27854061.v1 (2024).

Fu, C. Prunus mahaleb voucher SH240416, whole genome shotgun sequencing project. GenBank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.gca:GCA_048569315.1 (2025).

Fu, C. Prunus mahaleb voucher SH240416, whole genome shotgun sequencing project. GenBank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.gca:GCA_048569335.1 (2025).

Rhie, A., Walenz, B. P., Koren, S. & Phillippy, A. M. Merqury: reference-free quality, completeness, and phasing assessment for genome assemblies. Genome Biol. 21, 245 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported equally by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (32301411 and 32422053) and the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20230394).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.W. designed and led the project. C.F., M.L. and L.Y. collected the samples. C.F., Z.H. and M.L. performed data analyses and wrote the manuscript. Z.Z. provided the technical supports. Z.W., Z.H. and X.W revised the paper. C.F. and M.L. contributed equally. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fu, C., Li, M., Zhao, Z. et al. Haplotype-resolved chromosomal-level genome assembly of Prunus mahaleb. Sci Data 12, 805 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04873-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04873-5