Abstract

Soil contains a diverse community of organisms; these can include archaea, fungi, viruses, and bacteria. In situ identification of soil microorganisms is challenging. The use of genome-centric metagenomics enables the assembly and identification of microbial populations, allowing the categorization and exploration of potential functions living in the complex soil environment. However, the heterogeneity of the soil-inhabiting microbes poses a tremendous challenge, with their functions left unknown, and difficult to culture in lab settings. In this study, using genome assembling strategies from both field core samples and enriched monolith samples, we assembled 679 highly complete metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs). The ability to identify these MAGs from samples across a precipitation gradient in the state of Kansas (USA) provided insights into the impact of precipitation levels on soil microbial populations. Metabolite modeling of the MAGs revealed that more than 80% of the microbial populations possessed carbohydrate-active enzymes, capable of breaking down chitin and starch.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

The soil environment is host to many microbes with diverse functions1,2, but the high heterogeneity of the soil-associated microbial community results in challenging microbial culturing conditions in lab settings3,4. For example, some bacterial soil taxa have a slow growth rate or complex nutrient demands including the dependence on the “cross-feeding” in the natural soil environment5,6. These characteristics not only complicate the establishment of optimal growth conditions, but also require precise environmental mimicking to achieve successful cultivation. The difficulty of some microbes to be cultured has propelled the field of metagenomics to grow both in use and popularity7,8. Metagenomics has been used to categorize the complex microbes; their identity and functional potential, living in the environment9,10.

Metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) are assembled from the short fragments of DNA, and potentially increase the identity resolution of the microbial populations in a community11,12. The use of genome resolved metagenomes has enabled ground-breaking work in exploring potential functions across various communities like soil13, human and animal guts14, and many more15,16. Soil-associated MAGs are challenging to assemble in vivo17,18. One of the reasons is because of the complexity and biodiversity within the soil community, and the low presence of the soil microorganisms in the reference databases19,20. The soil environment contains many microorganisms like viruses, fungi, archaea, and bacteria, adding to the challenge of assembling microbial genomes19,21. Similarly, some soil-associated microbes are low in abundance, and getting enough coverage, coupled with limited information on these microbes22,23, makes assembling these microbial populations extremely hard to achieve17,24.

Understanding the distribution of bacterial populations across precipitation gradients is crucial for understanding how environmental factors such as moisture influence microbial diversity, function and overall ecosystem health. Microbes play essential roles in nutrient cycling25, organic matter decomposition2,26, and plant health27. All of which can be affected significantly with changes in precipitation28,29. With the ability to assemble genomes, and analyze them across different precipitation levels, thus, enabling the identification of adaptive traits and community shifts that respond to water availability, and therefore, provide insights into how ecosystems may respond to global climate change. This is vital for predicting and managing the impacts of shifting precipitation patterns on soil health, agricultural productivity, conservation efforts, and overall ecosystem stability13,30.

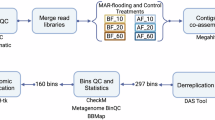

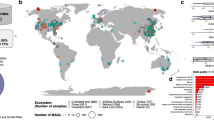

In this study, we assembled 679 metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) using a co-assembly strategy of 18 field soil core samples and 36 enriched monolith samples from two locations in Kansas, USA. The two locations were Hays, Kansas (Western Kansas; WKS), which has less yearly precipitation compared to Ottawa, Kansas (Eastern Kansas; EKS) (Fig. 1). One of the field core samples did not meet the minimum sequencing requirements, resulting in a total of 53 samples for this study. While co-assembly strategy has its limitations, we used this method to recover MAGs because (1) it resulted in higher read depth to enhance more robust assembly31, capturing the diversity across the system32; (2) it facilitates our comparison of the MAGs across the samples17,33; and (3) it used differential coverage across the samples to substantially improve our ability of recovering genomes from the metagenomes31,34. The monolith samples enriched the respective field soil cores which harbored a long history of land precipitation. This allowed us to successfully assemble soil-associated MAGs. We assigned the assembled microbial genomes as MAGs if they had a completion ≥70% and a redundancy <10%. Of all the assembled genomes, 5 MAGs had a completion of 100%; two of the five MAGs had a redundancy of 5.6%, with the rest having a redundancy of 1.4%, 1.4%, and 2.8% respectively (Supplementary Table S1). Of the ~ 42 ± 21 million metagenomic reads, an average of ~ 39 ± 19 million reads per sample passed quality control criteria, and were used for the 4 co-assemblies. The average total length of the MAGs was ~ 3 ± 1.4 Mbp, with the average number of contigs being ~ 464 ± 360. The average N50 was ~ 15991 ± 20615, and the average GC content was ~ 63 ± 8% (Supplementary Table S1).

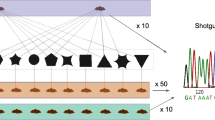

Experimental design demonstrating the sample collections and the bioinformatic workflow. The soil cores were collected from both the field and monolith samples; genomic DNA was extracted, and sent for shotgun sequencing. The bioinformatic workflow showed the processes used to resolve the non-redundant MAGs and metabolic modeling.

In this study, we resolved a large number of high-quality MAGs to the phyla Acidobacteriota (n = 96), Actinobacteriota (n = 271), and Proteobacteria (n = 105). The other MAGs were resolved to Bacteroidota (n = 1), Chloroflexota (n = 16), CSP1-3 (n = 1), Desulfobacterota (n = 10), Dormibacterota (n = 3), Eremiobacterota (n = 1), Firmicutes (n = 1), Gemmatimonadota (n = 17), Halobacteriota (n = 1), Methylomirabilota (n = 31), Myxococcota (n = 5), Nitrospirota (n = 7), Planctomycetota (n = 1), Tectomicrobia (n = 2), Thermoproteota (n = 42), Verrucomicrobiota (n = 36) (Fig. 2). There were 32 MAGs which were unidentified. There were 457 MAGs annotated to the genus level, with the highest number of MAGs annotated to the genera AV55 (n = 28) and Methyloceanibacter (n = 17). 395 MAGs were completed to the species level.

We observed that MAGs were more highly detected in the monolith as compared to the field samples, which highlighted the enrichment of the field samples in the monoliths (Fig. 3). Our results also highlighted the influence of locations and depth of sampling on the detection of the MAGs. Most of the MAGs were more detected in Eastern Kansas where the precipitation level is higher than the locations in Western Kansas. Furthermore, we also observed higher detection of the MAGs in the shallow region (5 cm) as compared to the deeper regions (15 cm and 30 cm) (Fig. 3; Supplementary Table S2).

We used Distilled and Refined Annotation of Metabolism (DRAM) to profile and compare the metabolic potentials of the MAGs. We observed that around 80% of the MAGs had enzymes capable of breaking down chitin, and ~ 75% of the MAGs contain enzymes that can metabolize starch (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table S3). We also observed that 17 MAGs possessed beta-galactan cleaving enzymes, while none of the MAGs could potentially degrade mucin. It was surprising to see that only ~25% of the MAGs contained enzymes necessary to convert nitrite to nitric oxide, while only 4 of 679 MAGs could convert nitrogen to ammonia. Based on the metabolic potential profiles, it appeared that the MAGs were more likely to be involved in denitrification rather than the nitrification process. Putting it all together, we showed that precipitation had a strong impact on the MAGs’ detection as well as their metabolic potentials, across the two locations.

Our findings provided insights into further understanding of how the soil microbial community, their essential functions and metabolism35,36 would be affected due to precipitation change and land use regime37,38. The availability of these high-resolution MAGs from this study would also provide the framework for exploring microbe-microbe interactions and microbial functional shifts under abiotic stresses39,40.

Methods

Experimental design and sample preparation

We used the Giddings probe (Giddings Machine Company, Windsor, CO, USA) to collect field soil samples (n = 3; depth 60 cm, diameter 5 cm) in June 2018 from 2 sites across the precipitation gradient (Fig. 1). The sites in Western (WKS) experience an average of 533 mm/year precipitation, and Eastern (EKS) Kansas average rainfall of 1045 mm/year41. Within the 3 plots at each precipitation site, we collected 1 soil core from 3 subplots. Soil collecting plots represented the land-use legacies: WKS (native/N: 38.84°N, 99.30°W, agricultural/Ag: 38.84°N, 99.31°W, and post-agricultural/PAg: 38.84°N, 99.32°W), and EKS (native/N: 38.18°N, 95.27°W, agricultural/Ag: 38.54°N, 95.25°W, and post-agricultural/PAg: 38.18°N, 95.27°W). Since we were interested in the representative samples of the land use rather than differences within plots, we then pooled and homogenized the soil cores to create 1 composite sample per plot. In this report, we were also interested in the gene distribution across the precipitation gradient. We aliquoted 25 g of soil for each depth segment (0–5 cm, 6–30 cm, 31–60 cm) for shotgun sequencing, and the rest of the samples were stored at −80 °C for archiving.

From August to October 2018, we collected monolith samples for the enrichment of soil microbial communities42. We collected intact soil cores (depth 60 cm, diameter 30 cm) from the same sites described above. We dried and stored monolith samples in the greenhouse (University of Kansas Field Station) until further processing. The monolith experiment was set up in April 2019 and continued for 6 months. Each monolith soil sample was rewetted and randomly assigned to the “dry” and “wet” watering treatment groups. The amount of water per treatment was determined by averaging the 30 years of EKS and WKS annual rainfall data and adding 50% of the total to account for the greenhouse conditions. As a result, the “dry” treatment group received 1000 mm/yr and the “wet” treatment reserved 2000 mm/yr. We also mimicked the summer rainstorm, by applying 450 mm/yr of each treatment in three 150 mm intense watering events. In November 2019, we harvested monolith samples, and segmented them according to the depth (0–5 cm, 6–30 cm, 31–60 cm) for shotgun sequencing, and the rest of the samples were stored at −80 °C for archiving.

Field soil samples were homogenized, and total genomic DNA was extracted using the DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit following the manufacturer’s protocol (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA). We extracted total DNA from 0.160 g of monolith soil samples using an Omega E.Z.N.A. Soil DNA Kit (Omega Biotek, Inc., Norcross, GA, United States) as per the manufacturer’s protocol with a slight modification. We mechanically lysed the cells in a Qiagen TissueLyser II (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) including bead-beating (20 rev/s, 2 mins) and vortexing (3 mins) prior to downstream DNA extraction steps. The extracted DNA from both kits was eluted to a 100-μL final volume. Extracted DNA was sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq. 6000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) at the University of Kansas Medical Center Genome Sequencing Facility. We used an S1 flow cell to undertake a 150-paired sequencing strategy using Nextera DNA Flex library preparation.

Bioinformatics

We co-assembled reads from 12 “metagenomic sets” - 6 from the field and 6 from the monolith soils based on the geographical locations (WKS, EKS) and their soil depths (0–5 cm, 6–30 cm, 31–60 cm). We automated our metagenomics bioinformatics workflow using the ‘anvi-run-workflow’43 in anvi’o v7.144,45. The workflows use Snakemake43 to implement numerous tasks. Details of each process as outlined below:

We used the program ‘iu-filer-quality-minoche’ to process the short metagenomic reads and removed low-quality reads accordingly46. We used MEGAHIT v1.2.931 to co-assemble quality-filtered short reads into longer contiguous sequences (contigs). Following the assembling of contigs, we used ‘anvi-gen-contigs- database’ to compute k-mer frequencies and identify open reading frames (ORFs) using Prodigal v2.6.347; ‘anvi-run-hmms’ to identify sets of bacterial and archaeal single-copy core genes using HMMER v.3.2.148; ‘anvi-run-ncbi-cogs’ to annotate ORFs from NCBI’s Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COGs)49; and ‘anvi-run-kegg-kofams’ to annotate ORFs from KOfam HMM databases of KEGG orthologs50. Next, we mapped metagenomic short reads to contigs using Bowtie2 v2.3.551 and profiled the BAM files using ‘anvi-profile’ with a minimum contig length of 1000 bp. Finally, we used ‘anvi-merge’ to combine all profiles into an anvi’o merged profile for all downstream analyses. For the construction of metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs), we first used ‘anvi-cluster-contigs’ to group contigs into initial bins using CONCOCT v1.1.052, and used ‘anvi-refine’ to manually curate the bins based on tetranucleotide frequency and different coverage across the samples. We marked bins that were more than 70% complete and less than 10% redundant as MAGs. The completion and redundancy values of the MAGs were based on matching single copy genes in the MAGs with multiple hidden Markov models (HMM): Bacteria_7153, Archaea_7654, and Protista_83. Finally, we used ‘anvi-compute-genome-similarity’ to calculate the average nucleotide identity (ANI) of our MAGs using PyANI v0.2.955, and identified non-redundant MAGs.

We annotated the non-redundant MAGs with Distilled and Refined Annotation of Metabolism (DRAM), to provide a metabolic profile for each of the MAGs56. We used Prodigal47 v.2.6.3 to detect open reading frames (ORFs) and predict their amino acid sequences. We then used DRAM to search for all amino acid sequences against KEGG57, UniRef9058, and MEROPS59 using MMseqs. 260, with the best hits (defined by bit score with a default minimum threshold of 60). We also used DRAM to perform HMM profile searches of the Pfam61 database, and HMMER362 for dbCAN63, with coverage length > 35% of the model and e-value < 10–15 to be considered a hit 40.

Data Records

The shotgun metagenome reads as well as the sequences for the MAGs generated from this study are publicly available on the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under BioProject PRJNA855256, SRR20019782-2001983464. All other analyzed data in the form of databases and fasta files are also accessible in github (https://github.com/SonnyTMLee/Recovery-of-679-soil-MAGs)65, and also available on NCBI GenBank66 - see Supplementary Table 1 for the individual genome (MAGs) accession numbers.

Technical Validation

All data processing steps, and software used in this study are described in the “Methods” section. The DNA yield and quality were measured using the NanoDrop One C (NanoDrop Technologies Inc, Wilmington, DE, USA) and a Qubit 4 Fluorometer dsDNA BR Assay Kit (Life Technologies, Paisley, UK).

Code availability

All intermediate databases, files and MAGs fasta are available in github (https://github.com/SonnyTMLee/Recovery-of-679-soil-MAGs)65. Bioinformatic codes to generate the MAGs are also available in github.

References

Ramoneda, J. et al. Building a genome-based understanding of bacterial pH preferences. Sci Adv 9, eadf8998 (2023).

Hoorman, J. J. The role of soil bacteria. Ohio State University Extension, Columbus 1–4 (2011).

Nguyen, T. M. et al. Effective Soil Extraction Method for Cultivating Previously Uncultured Soil Bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 84 (2018).

Lloyd, K. G., Steen, A. D., Ladau, J., Yin, J., Crosby, L. Phylogenetically Novel Uncultured Microbial Cells Dominate Earth Microbiomes. mSystems 3 (2018).

Hibbing, M. E., Fuqua, C., Parsek, M. R. & Peterson, S. B. Bacterial competition: surviving and thriving in the microbial jungle. Nat Rev Microbiol 8, 15–25 (2009).

Butaitė, E., Baumgartner, M., Wyder, S. & Kümmerli, R. Siderophore cheating and cheating resistance shape competition for iron in soil and freshwater Pseudomonas communities. Nat Commun 8, 414 (2017).

Waschulin, V. et al. Biosynthetic potential of uncultured Antarctic soil bacteria revealed through long-read metagenomic sequencing. ISME J 16, 101–111 (2022).

Rondon, M. R. et al. Cloning the soil metagenome: a strategy for accessing the genetic and functional diversity of uncultured microorganisms. Appl Environ Microbiol 66, 2541–2547 (2000).

Hugenholtz, P., Tyson, G. W. Metagenomics. Nature Publishing Group UK. https://doi.org/10.1038/455481a. Retrieved 21 November 2023 (2008).

Sorbara, M. T. et al. Functional and Genomic Variation between Human-Derived Isolates of Lachnospiraceae Reveals Inter- and Intra-Species Diversity. Cell Host Microbe 28, 134–146.e4 (2020).

Almeida, A. et al. A new genomic blueprint of the human gut microbiota. Nature 568, 499–504 (2019).

Tyson, G. W. et al. Community structure and metabolism through reconstruction of microbial genomes from the environment. Nature 428, 37–43 (2004).

Nelkner J et al. Effect of Long-Term Farming Practices on Agricultural Soil Microbiome Members Represented by Metagenomically Assembled Genomes (MAGs) and Their Predicted Plant-Beneficial Genes. Genes 10 (2019).

Chen, C. et al. Expanded catalog of microbial genes and metagenome-assembled genomes from the pig gut microbiome. Nat Commun 12, 1–13 (2021).

Wilkins, L. G. E., Ettinger, C. L., Jospin, G. & Eisen, J. A. Metagenome-assembled genomes provide new insight into the microbial diversity of two thermal pools in Kamchatka, Russia. Sci Rep 9, 3059 (2019).

Nathani, N. M. et al. 309 metagenome assembled microbial genomes from deep sediment samples in the Gulfs of Kathiawar Peninsula. Sci Data 8, 194 (2021).

Alteio LV et al. Complementary Metagenomic Approaches Improve Reconstruction of Microbial Diversity in a Forest Soil. mSystems 5 (2020).

Geisen, S. et al. A methodological framework to embrace soil biodiversity. Soil Biol Biochem 136, 107536 (2019).

Fierer, N. et al. Metagenomic and small-subunit rRNA analyses reveal the genetic diversity of bacteria, archaea, fungi, and viruses in soil. Appl Environ Microbiol 73, 7059–7066 (2007).

Curtis, T. P., Sloan, W. T. & Scannell, J. W. Estimating prokaryotic diversity and its limits. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99, 10494–10499 (2002).

White RA et al Moleculo Long-Read Sequencing Facilitates Assembly and Genomic Binning from Complex Soil Metagenomes. mSystems 1 (2016).

Jin, H. et al. Hybrid, ultra-deep metagenomic sequencing enables genomic and functional characterization of low-abundance species in the human gut microbiome. Gut Microbes 14, 2021790 (2022).

Riley, R. et al. Terabase-Scale Coassembly of a Tropical Soil Microbiome. Microbiol Spectr 11, e0020023 (2023).

Sun, Y. et al. Genome enrichment of rare and unknown species from complicated microbiomes by nanopore selective sequencing. Genome Res 33, 612–621 (2023).

Jiao, S., Xu, Y., Zhang, J., Hao, X., Lu, Y. Core Microbiota in agricultural soils and their potential associations with nutrient cycling. mSystems 4 (2019).

Yuan, Q. et al. Soil bacterial community mediates the effect of plant material on methanogenic decomposition of soil organic matter. Soil Biol Biochem 116, 99–109 (2018).

Kumar, A., Singh, S., Mukherjee, A., Rastogi, R. P. & Verma, J. P. Salt-tolerant plant growth-promoting Bacillus pumilus strain JPVS11 to enhance plant growth attributes of rice and improve soil health under salinity stress. Microbiol Res 242, 126616 (2021).

Zuo, X. et al. Contrasting relationships between plant-soil microbial diversity are driven by geographic and experimental precipitation changes. Sci Total Environ 861, 160654 (2023).

Fahey, C., Koyama, A., Antunes, P. M., Dunfield, K. & Flory, S. L. Plant communities mediate the interactive effects of invasion and drought on soil microbial communities. ISME J 14, 1396–1409 (2020).

Sarkar, S. et al. Pseudomonas cultivated from Andropogon gerardii rhizosphere show functional potential for promoting plant host growth and drought resilience. BMC Genomics 23, 784 (2022).

Li, D., Liu, C.-M., Luo, R., Sadakane, K. & Lam, T.-W. MEGAHIT: an ultra-fast single-node solution for large and complex metagenomics assembly via succinct de Bruijn graph. Bioinformatics 31, 1674–1676 (2015).

Li, D. et al. MEGAHIT v1.0: A fast and scalable metagenome assembler driven by advanced methodologies and community practices. Methods 102, 3–11 (2016).

Nelkner, J. et al. Abundance, classification and genetic potential of Thaumarchaeota in metagenomes of European agricultural soils: a meta-analysis. Environ Microbiome 18, 26 (2023).

Cleary, B. et al. Detection of low-abundance bacterial strains in metagenomic datasets by eigengenome partitioning. Nat Biotechnol 33, 1053–1060 (2015).

Nascimento Lemos, L. et al. Metagenome assembled-genomes reveal similar functional profiles of CPR/Patescibacteria phyla in soils. Environ Microbiol Rep 12, 651–655 (2020).

Li, Z. et al. Genome-Resolved Proteomic Stable Isotope Probing of Soil Microbial Communities Using 13CO2 and 13C-Methanol. Front Microbiol 10, 2706 (2019).

Bei, Q. et al. Extreme summers impact cropland and grassland soil microbiomes. ISME J 17, 1589–1600 (2023).

Nelson, A. R. et al. Wildfire-dependent changes in soil microbiome diversity and function. Nat Microbiol 7, 1419–1430 (2022).

Braga, L. P. P. et al. Genome-resolved metagenome and metatranscriptome analyses of thermophilic composting reveal key bacterial players and their metabolic interactions. BMC Genomics 22, 652 (2021).

Bulgarelli, D. et al. Structure and function of the bacterial root microbiota in wild and domesticated barley. Cell Host Microbe 17, 392–403 (2015).

Galliart, M. et al. Local adaptation, genetic divergence, and experimental selection in a foundation grass across the US Great Plains’ climate gradient. Glob Chang Biol 25, 850–868 (2019).

Sarkar, S. et al. Ammonia-oxidizing archaea and bacteria differentially contribute to ammonia oxidation in soil under precipitation gradients and land legacy. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.08.566028 (2023).

Shaiber, A. et al. Functional and genetic markers of niche partitioning among enigmatic members of the human oral microbiome. Genome Biol 21, 292 (2020).

Eren, A. M. et al. Community-led, integrated, reproducible multi-omics with anvi’o. Nat Microbiol 6, 3–6 (2021).

Eren, A. M. et al. Minimum entropy decomposition: unsupervised oligotyping for sensitive partitioning of high-throughput marker gene sequences. ISME J 9, 968–979 (2015).

Minoche, A. E., Dohm, J. C. & Himmelbauer, H. Evaluation of genomic high-throughput sequencing data generated on Illumina HiSeq and genome analyzer systems. Genome Biol 12, R112 (2011).

Hyatt, D. et al. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics 11, 119 (2010).

DIE Himmers – Startseite. http://himmer.org. Retrieved 2 January (2024).

COG - NCBI. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/research/cog (2024). Retrieved 2 January.

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 28, 27–30 (2000).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 9, 357–359 (2012).

Alneberg, J. et al. Binning metagenomic contigs by coverage and composition. Nat Methods 11, 1144–1146 (2014).

Hug, L. A. et al. A new view of the tree of life. Nat Microbiol 1, 16048 (2016).

Lee, M. D. GToTree: a user-friendly workflow for phylogenomics. Bioinformatics 35, 4162–4164 (2019).

Pritchard, L., Glover, R. H., Humphris, S., Elphinstone, J. G. & Toth, I. K. Genomics and taxonomy in diagnostics for food security: soft-rotting enterobacterial plant pathogens. Anal Methods 8, 12–24 (2015).

Shaffer, M. et al. DRAM for distilling microbial metabolism to automate the curation of microbiome function. Nucleic Acids Res 48, 8883–8900 (2020).

Kanehisa, M., Goto, S., Furumichi, M., Tanabe, M. & Hirakawa, M. KEGG for representation and analysis of molecular networks involving diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res 38, D355–60 (2010).

Suzek, B. E., Huang, H., McGarvey, P., Mazumder, R. & Wu, C. H. UniRef: comprehensive and non-redundant UniProt reference clusters. Bioinformatics 23, 1282–1288 (2007).

Rawlings, N. D. et al. The MEROPS database of proteolytic enzymes, their substrates and inhibitors in 2017 and a comparison with peptidases in the PANTHER database. Nucleic Acids Res 46, D624–D632 (2018).

Mirdita, M., Steinegger, M. & Söding, J. MMseqs. 2 desktop and local web server app for fast, interactive sequence searches. Bioinformatics 35, 2856–2858 (2019).

Mistry, J. et al. Pfam: The protein families database in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res 49, D412–D419 (2021).

Wheeler, T. J. & Eddy, S. R. nhmmer: DNA homology search with profile HMMs. Bioinformatics 29, 2487–2489 (2013).

Yin, Y. et al. dbCAN: a web resource for automated carbohydrate-active enzyme annotation. Nucleic Acids Res 40, W445–51 (2012).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP385305

Kazarina, A. et al. Recovery of 679 metagenome-assembled genomes from different soil depths along a precipitation gradient. GitHub https://github.com/SonnyTMLee/Recovery-of-679-soil-MAGs

Kazarina, A. et al. Recovery of 679 metagenome-assembled genomes from different soil depths along a precipitation gradient. GenBank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/bioproject:PRJNA855256

Acknowledgements

The work is supported by the National Science Foundation under Award No. OIA-1656006 and matching support from the State of Kansas through the Kansas Board of Regents. This study was also funded by the United States Department of Agriculture, National Institute of Food and Agriculture (USDA NIFA), under the Award Number: 2020-67019-31803. This work is also supported by the National Science Foundation under Award No. 2238633. We are thankful to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant support - Kansas Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center (NIH U54 HD 090216), the Molecular Regulation of Cell Development and Differentiation – COBRE (P30 GM122731-03) - the NIH S10, High-End Instrumentation Grant (NIH S10OD021743) and the Frontiers CTSA grant (UL1TR002366), at the University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS 66160. We appreciate the Kansas Medical Center Genomics Core for the metagenomic data generated. We are thankful for the help extended by Paige M. Hansen, Willow Kessler, Terry D. Loecke, Benjamin A. Sikes in the coordination of the collection of samples.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.K. and H.W. performed the data analysis and wrote the manuscript. S.T.M.L. and S.S. conceptualized and designed the study. S.T.M.L. collected samples. S.S. performed the monolith experiments and extracted DNA for the Illumina sequencing. S.T.M.L. supervised the study. All authors reviewed and approved of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kazarina, A., Wiechman, H., Sarkar, S. et al. Recovery of 679 metagenome-assembled genomes from different soil depths along a precipitation gradient. Sci Data 12, 521 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04884-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04884-2

This article is cited by

-

A genomic view of Earth’s biomes

Nature Reviews Genetics (2026)

-

Bioactive molecules unearthed by terabase-scale long-read sequencing of a soil metagenome

Nature Biotechnology (2025)