Abstract

Accurate estimation of surface ocean pCO2 is crucial for understanding the ocean’s role in the global carbon cycle and its response to climate change. In this study, we employ a machine learning algorithm to correct the deviations in high-resolution (1/12°) model simulations of surface pCO2 from the INCOIS-BIO-ROMS model (pCO2model) for the period 1980–2019, using available observations (pCO2obs). We train the XGBoost model to generate spatio-temporal deviations (pCO2obs − pCO2model) of pCO2model. The interannually and climatologically varying deviations are then added back to the original model separately, which results in an improved surface pCO2 data product. A comparison of our surface pCO2 data product with moored observations, gridded SOCAT, CMEMS-LSCE-FFNN, and OceanSODA demonstrates an improvement by approximately 40% ± 3.31% in RMSE. Further analysis reveals that adding climatological deviations to pCO2model results in greater improvements than adding interannual deviations. This analysis underscores the ability of machine learning algorithms to enhance the accuracy of model-simulated surface pCO2 outputs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Since the Industrial Revolution, anthropogenic activities such as deforestation, changes in land use and cover, the manufacturing of cement, and burning fossil fuels have contributed to the rise in atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2)1. Approximately 50% of the CO2 released by human activities is absorbed by both land and water2. Based on the Global Carbon Budget, 20233, the ocean absorbed about 26% of the total CO2 during 2013-2022.

The coasts of the Indian Ocean (IO) host close to 30% of the world’s population4,5. As a result, these regions are subject to high anthropogenic pressure. The high freshwater influx from rivers in the north Indian Ocean, seasonal reversing currents due to the seasonal reversal of monsoonal winds, and high aerosol deposition severely affect the carbon cycle of the north Indian region6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13. Further, climatic events like El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) are observed to affect the partial pressure of the CO2 (pCO2) and pH variability in the IO region14,15,16,17.

As a part of the Regional Carbon Cycle Assessment and Processes-2 (RECCAP2) project, multiple approaches, such as interpolated observational climatology, hindcast models, observation-based surface pCO2 (empirical models), and atmospheric inversion models were utilized for estimating net air-sea CO2 fluxes between 1985 and 2018. A high-resolution (1/12°) regional hindcast model, known as INCOIS-BIO-ROMS (IBR_Original), was configured following the RECCAP2 ocean modeling protocol for the regional oceans. The IBR_Original model simulated outputs from 1980-2019 were part of the RECCAP2 assessment process5 and used to study the ocean acidification over the IO region16.

Regional ocean models provide valuable insights to oceanic pCO2 variability and trends but often exhibit significant biases due to their limitations in representing small-scale processes and associated uncertainties in model parameterizations. Although observations are essential to understand surface pCO2 variability, the availability of spatially and temporally varying observations is limited, especially in the IO. This data scarcity poses a challenge for validating and improving observations-based model predictions. The errors between model outputs and observations can hinder our ability to accurately estimate surface pCO2 and associated air-sea CO2 flux, underscoring the need for advanced correction techniques that can bridge the gap between modeled and observed surface pCO2 values.

Machine learning (ML) algorithms offer a promising method to improve the quality of model-simulated surface pCO2 by correcting its biases18,19 with respect to the observations. The ML algorithms are also widely applied to predict surface pCO2 using observations13,20,21,22,23,24. ML algorithms can capture complex, nonlinear relationships between target and predictor variables13,20– 24. Integrating ML-based corrections with existing model outputs makes it possible to produce more reliable and high-resolution surface pCO2 estimates that better reflect observed conditions19.

This study aims to produce an ML-based improved surface pCO2 data product by combining the available observations and the high-resolution IBR_Original model-simulated outputs for the IO region from 1980 to 2019. This data product will be useful to estimate more accurate air-sea CO2 flux and identify areas in the IO that act as source (releasing CO2 into the atmosphere) and sink (absorbing CO2 from the atmosphere) of CO2. With improved accuracy in modeled pCO2, we can gain a better understanding of IO acidification in response to the ever-changing climate.

Methods

For improving model-simulated surface pCO2 using heterogeneous in-situ observations across IO, we divided the IO region into four sub-regions (Fig. 1) as (a) the Arabian Sea (0° N–30° N; 30° E–78° E), (b) the Bay of Bengal (0° N–30° N; 78° E–110° E), (c) Central IO (0° N–18° S; 30° E–120° E) and (d) Southern IO (18° S–30° S; 30° E–120° E). This division is based on the complexity of regional physical processes in the IO region5.

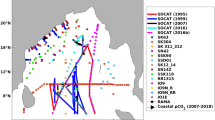

Represents the study region (Indian Ocean (IO)) and the sub-regions (Arabian Sea, Bay of Bengal, Central IO, and Southern IO). (a) Shows the yearly variations in pCO2 observations acquired from the SOCAT (Surface Ocean CO2 Atlas) data, and (b) is a representation of the yearly variation in observations from SAS (Sridevi and Sarma) data.

We assume that the surface pCO2 deviant (observed pCO2 (pCO2obs) - modeled pCO2 (pCO2model)) is a function of surface temperature (SST), surface salinity (SSS), mixed layer depth (MLD), surface dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC), surface nitrate (NO3), and surface chlorophyll-a (CHL). The changes in the above-mentioned ocean variables significantly control the variability of surface pCO2. The variables SST, SSS, MLD, DIC, NO3, and CHL are considered as the proxies of major ocean processes such as ocean thermodynamics, solubility, stratification, and biological pump. In this study, we predict the spatio-temporal varying surface pCO2 deviants using an ML model. These predicted pCO2 deviants are then added to the pCO2model to get the corrected surface pCO2. Figure 2 is a schematic diagram showing the complete methodology adopted for this study. The details of the data required for this study, description of the ML model, and mapping methodology are described below.

Data Acquisition

We acquire pCO2obs from two different sources. The first source is the Surface Ocean CO2 Atlas (SOCAT) (https://socat.info/index.php/version-2022/)25 available for the period 1984 to 2019 in the IO. The availability of spatio-temporaral varying surface pCO2 observations from SOCAT is shown in Fig. 1a. In addition to the SOCAT database, the surface pCO2 observations are also collected from different Indian scientific cruises denoted as SAS (Sridevi and Sarma) data11. The SAS data is available from 1991 to 2019. More details of the SAS data are available in our recent study13. Figure 1b shows the spatio-temporal availability of the surface pCO2 from the SAS dataset. Data collection and quality control methods are explicitly available in the literature corresponding to each of these datasets11,25.

The monthly data frequency of available surface pCO2 observations (pCO2obs) (SOCAT and SAS) from various sources is shown in Fig. 3 for four sub-regions of the Indian Ocean (IO), namely the Arabian Sea (AS), the Bay of Bengal (BoB), the Central IO and the Southern IO. In the AS region, a significantly higher number of observations is recorded from May to September compared to other months. Similarly, a large number of observations are available from February to May in the BoB. Observations in the AS and Central IO peak during the southwest monsoon season (June–September), while the pre-monsoon season (March–May) sees the maximum number of observations in the BoB and Southern IO regions (Fig. 3). This analysis highlights potential sources of prediction uncertainty due to data unavailability during certain periods. As the number of observations increases, the accuracy of predictions is expected to improve. Despite these temporal gaps, the data provide excellent spatial coverage across the IO region (Fig. 1).

Monthly observations of pCO2 (SOCAT+SAS) are divided into four sub-regions (a)–(d) of the Indian Ocean (IO). The blue bars denote the northeast monsoon season (December-February), while the green, yellow, and red bars represent the pre-monsoon (March-May), summer monsoon (June-September), and post-monsoon (October-November) seasons, respectively.

The input data of the ocean state variables (SST, SSS, MLD, DIC, NO3, and CHL) are extracted from the IBR_Original model at locations at which pCO2obs are available from different sources (SOCAT and SAS). We also extracted the surface pCO2 from IBR_Original i.e. pCO2model at these same locations. The IBR_Original model outputs are of 1/12° spatial resolution and are available from 1980 to 2019 on a monthly scale. The IBR_Original model outputs used in this study have been already validated and utilized in our previous studies5,16. Hence, we encourage readers to refer to our previous studies5,16 for more details on the IBR_Original model configuration.

We checked the data distribution for each sub-region of IO before using the data for training and predictions. The MLD, CHL, and NO3 data are converted to a normal distribution by taking their log transformation. Since ML models are sensitive to outliers (>3σ), the outliers are removed from the available data for each sub-region of IO.

The Bay of Bengal Ocean Acidification (BOBOA) mooring is the only point-source observation of surface pCO2 available from 2014-2018 in the IO region. Hence, it is used as an independent dataset for assessing improvements in surface pCO2 at the BOBOA mooring location. The BOBOA mooring is located at 15° N, 90° E. The observation data at this location is converted to a monthly frequency before being compared with the simulated pCO2. The surface pCO2 data from BOBOA is downloaded from https://www.pmel.noaa.gov/co2/story/BOBOA.

We acknowledge that the scarcity of gap-free spatio-temporal observations is a common challenge in ocean carbonate variable studies. One approach for independent validation is to remove a specific cruise line from the dataset. However, this would reduce the number of available observations for developing ML models, potentially affecting their overall performance. More importantly, cruise lines are region-specific and often lack broad temporal coverage, making it unjustified to assess improvements across the entire IO based solely on validation using a single cruise line. Given that the corrected pCO2 dataset has a high spatial resolution of 1/12° and spans from 1980 to 2019, it is essential to evaluate its improvements across the entire IO region.

The gridded SOCAT is a monthly 1° binned data product prepared from SOCAT cruise observations25. The surface pCO2 from IBR_Original has a spatial resolution of 0.083°. The pCO2 values corresponding to each cruise location are extracted from this dataset, and the difference is used as our target variable (pCO2 deviant). This extraction is performed using the nearest-neighbour interpolation method. Nevertheless, the SOCAT 1° data product bins values into a 1° grid without interpolation, resulting in slight differences from the values used for training. Therefore, we use the SOCAT 1° dataset to assess whether the final product demonstrates an improvement or decline in surface pCO2 values. The pCO2model and corrected pCO2 datasets have a monthly frequency, making the monthly gridded SOCAT data particularly useful for evaluating the improvement of the corrected pCO2 datasets compared to observations. In the IO region, gridded SOCAT data is available from 1984 to 2019. This data can be downloaded from https://socat.info/index.php/data-access/.

ML-based products are important as they provide spatio-temporally gap-free estimates. In this study, we use two high-resolution (0.25° × 0.25°) gridded ML-based data products (CMEMS-LSCE-FFNN (Copernicus Marine Environment Monitoring Service–Laboratoire des Sciences du Climat et de l’Environnement feed-forward neural network)23 and OceanSODA (OceanSODA-ETHZv2)24). For this study, the CMEMS-LSCE-FFNN (OceanSODA) data is taken from 1985 (1982) to 2019. The CMEMS-LSCE-FFNN data is downloaded from https://data.ipsl.fr/catalog/srv/eng/catalog.search#/metadata/a2f0891b-763a-49e9-af1b-78ed78b16982. While the OceanSODA data is downloaded from https://zenodo.org/records/11206366. Although these data products were developed using SOCAT observations, they employ different methodologies for constructing surface pCO2, leading to inherent differences among them. Additionally, the availability of data products with varying spatial resolutions, such as CMEMS-LSCE-FFNN and OceanSODA, enables a more rigorous comparison of our product. This comprehensive evaluation enhances confidence in the reliability of the final product. Table 1 summarizes all the data used in this study.

Splitting and Scaling Data

In this study, SST, SSS, MLD, NO3 concentration, and CHL from IBR_Original are used as predictors. The deviation between the pCO2obs values (from SOCAT and SAS datasets) and the pCO2model values [pCO2obs–pCO2model] serves as the target. The data from each of the four sub-regions are randomly divided into training (80%) and testing (20%) datasets using the Scikit-Learn module26. These test datasets are kept separate for each sub-region and are exclusively used to validate the model’s performance, ensuring unbiased evaluation. To train the models and prevent the overfitting issue, a 10-fold cross-validation technique is applied. In this approach, the training dataset is split into 10 subsets (folds). The model is trained on nine of these folds and validated on the remaining one, with the process repeated for all folds.

Machine Learning Algorithm

The study utilizes an advanced ML algorithm, eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGB), to produce an improved version of pCO2model for the IO region during the period 1980-2019. The details of the XGBoost algorithm are given below.

-

eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGB) The XGB algorithm27 is a supervised learning algorithm that belongs to the decision tree-based boosting algorithm family. The XGB algorithm was created by increasing the computational speed and performance of the gradient-boosted algorithm. Previous studies highlight the algorithm’s superior computational speed, accuracy, and overall performance compared to other machine learning algorithms13,19,22,28. The proven capability of this advanced ML algorithm in previous studies motivates us to employ this XGB algorithm to correct the pCO2model for each of the four sub-regions of the IO. This algorithm starts with an initial guess, and then trees are added sequentially. Each tree tries to improve the ensemble’s performance by minimizing a loss function. In this study, the model developed using the XGB algorithm is hereafter referred to as the ‘XGB-model.’

Performance of the tuned XGB-model

The XGB-model has tunable hyper-parameters. Following previous literature13,22, we decided to use the Optuna optimization29 to tune the hyper-parameters. The hyper-parameters range, and final optimized values for each of the sub-regions are shown in Table 2. To determine whether the tuned XGB-model is neither overfitting nor underfitting, it is essential to evaluate the performance of the XGB-model using the 20% test dataset set kept aside during the 80:20 data split for each sub-region of the IO. The performance of the four individual XGB-models developed for these sub-regions is summarized in Table 3. Similar RMSE values for the training and testing datasets across the respective sub-regions indicate consistent and reliable XGB-model performance throughout all sub-regions.

Best Estimate and Uncertainty

To quantify the uncertainty associated with predicting pCO2 deviants, we adopt a method similar to the bootstrapping technique in statistics21,23. This approach requires generating a large number of models, where the average prediction provides the best estimate of the target (pCO2 deviants), and the standard deviation (SD, 1-σ) quantifies the predictive uncertainty.

To achieve this, we generate 150 training datasets for each sub-region by randomly extracting 80% of the data from the training set used during hyperparameter tuning. This process results in 150 independently trained XGB-models. Subsequently, we create ensembles of varying sizes, from a minimum of 2 to a maximum of 150 XGB-models. The optimal ensemble size, defined as the size at which the RMSE (evaluated against the test dataset) stabilizes with no significant improvement, is then identified for each sub-region. As shown in Fig. 4, the optimal ensemble size is 140 for the AS and the Central IO, while it is 130 for the BoB and the Southern IO.

Mapping Method

To generate the spatio-temporal variation in pCO2 deviants for each sub-region, spatio-temporal inputs (SST, SSS, MLD, DIC, NO3 concentration, and CHL) from IBR_Original (covering the period 1980–2019) are fed into each of the 140 XGB-models (for the AS and the Central IO) or 130 XGB-models (for the BoB and the Southern IO). As mentioned in the previous section, the average output of these algorithms provides the best estimate of the spatio-temporal pCO2 deviants, while the standard deviation quantifies the associated uncertainty for the period 1980–2019. Figure 5 shows the domain-averaged pCO2 deviants and their corresponding uncertainties for each sub-region. These spatio-temporal pCO2 deviants are then added back to the pCO2model (at each grid cell) to derive the corrected pCO2.

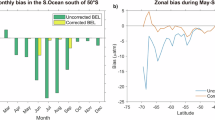

Here, we examine two different approaches for incorporating spatial deviants into the pCO2 correction process. In the first approach, the interannual deviants are added to the pCO2model, resulting in the interannually corrected pCO2 dataset (pCIBR_Int). In the second approach, only the climatological mean of the deviants is added to the pCO2model, producing the climatologically corrected pCO2 dataset (pCIBR_Clim). Since the variability of the climatological deviance is greater than that of the interannual variability, we aim to determine which approach yields better results. The data products generated using both methods are extensively validated against BOBOA moored buoy-based observations, gridded 1° × 1° SOCAT dataset, and two additional gridded data products (CMEMS-LSCE-FFNN and OceanSODA) to identify the most effective method for correcting surface pCO2 data.

Data Records

The long-term high-resolution corrected surface pCO2 datasets (pCIBR_Clim and pCIBR_Int) produced for the IO region can be accessed from https://zenodo.org/records/1461473930. This product has a monthly temporal resolution and a spatial resolution of 1/12°. The data is available from 1980-2019. From the same link, the users can access the input data used to correct pCO2model and the pCO2 deviants, along with the associated uncertainty derived from the XGB-models. All the data are provided in a single NetCDF file.

Technical Validation

A comparison of the pCO2model and the corrected surface pCO2 data products (pCIBR_Int and pCIBR_Clim) has been carried out against the time series observations of surface pCO2 from the BOBOA moored buoy location (Fig. 6). This study employs three statistical metrics (Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and Taylor Skill Score (TSS)) to evaluate the performance of the corrected pCO2 data against the pCO2model using the BOBOA mooring-based observations. As summarized in Table 4, the RMSE between pCIBR_Clim (pCIBR_Int) and the BOBOA pCO2 observations decreased by approximately 37.84% ± 2.35% (40.63% ± 0.38%) compared to the RMSE between the pCO2model and BOBOA. Similarly, the MAE decreased by about 50.43% ± 1.85% for pCIBR_Int and 44.46% ± 5.84% for pCIBR_Clim. The TSS measures the agreement between model outputs and reference data, particularly with respect to variability, where a value close to 1 indicates a perfect match. The pCO2model demonstrates a good TSS of 0.87. However, the corrections applied in this study further improve the TSS by approximately 1.11% ± 0.77% for pCIBR_Int and 2.23% ± 0.62% for pCIBR_Clim. Based on the comparison with BOBOA observations, we conclude that both correction methods (pCIBR_Clim and pCIBR_Int) provide significant improvements to the pCO2model. This comparison further indicates that both the methods perform very close to each other.

In addition to validation at a moored buoy location, a comparison of pCIBR_Int and pCIBR_Clim data products has been carried out with the gridded SOCAT, CMEMS-LSCE-FFNN, and OceanSODA datasets to evaluate the spatial improvement in the surface pCO2 (Figs. 7, 8, and 9). The corrected pCO2 datasets (pCIBR_Int and pCIBR_Clim) have a resolution of 1/12°, which is finer than all the reference datasets. Therefore, we re-grid the corrected pCO2 data to match the grid of the reference datasets using the nearest-interpolation method.

The figure represents the changes in RMSE (ΔRMSE, first row), MAE (ΔMAE, second row), and TSS (ΔTSS, third row) between pCIBR_Int (first column) or pCIBR_Clim (second column) and pCO2model while comparing each of them to the gridded SOCAT product. Negative values (blue) in ΔRMSE and ΔMAE indicate improvement over pCO2model. While positive values (red) in ΔTSS represent an improvement over pCO2model.

Figure 7 shows the difference in RMSE between pCIBR_Int (Fig. 7a) or pCIBR_Clim (Fig. 7b) and pCO2model when compared with the gridded SOCAT data. Both panels (Fig. 7a and b) demonstrate a considerable reduction in RMSE across the IO domain. Specifically, the RMSE decreases by approximately 40.43% ± 4.39% for pCIBR_Int and 38.87% ± 4.92% for pCIBR_Clim. The second and third rows of Fig. 7 show the differences in MAE and TSS between the corrected pCO2 outputs (from both methods) and pCO2model when compared to SOCAT. The reduction in MAE is more pronounced for pCIBR_Clim (≈ 40% ± 5%) compared to pCIBR_Int (≈ 35% ± 4%). The third row of Fig. 7, which shows TSS differences, contains fewer grid cells than the first and second rows. This is because TSS accounts for data availabilityS, and the gridded SOCAT dataset bins cruise line data into a 1° mesh, resulting in fewer cells with repeated data values. The grid cells displayed in the third row have at least three observation data points per cell. An increase in TSS of approximately 7.13% ± 0.22% is observed for pCIBR_Int, while pCIBR_Clim shows an increase of about 5.15% ± 0.76%. Nevertheless, the availability of a limited number of spatio-temporal varying surface pCO2 observations makes it challenging to conclusively determine which method (pCIBR_Int or pCIBR_Clim) better improves the pCO2model. However, the analysis clearly indicates that both methods result in significant improvements over SSthe pCO2model.

CMEMS-LSCE-FFNN and OceanSODA are observation-based reconstructed data products that provide high-resolution, gap-free, spatio-temporally varying gridded surface pCO2. Both datasets were developed using different ML methods to predict long-term changes in surface pCO2. These data products are widely recognized by the international scientific community for their significant contributions to advancing ocean carbon cycle research and improving our understanding of how environmental changes influence air-sea CO2 flux dynamics. Accordingly, we utilize these datasets to perform robust spatio-temporal validation, as shown in Figs. (8 and 9).

The figure represents the changes in RMSE (ΔRMSE, first row), MAE (ΔMAE, second row), and TSS (ΔTSS, third row) between pCIBR_Int (first column) or pCIBR_Clim (second column) and pCO2model while comparing each of them to the CMEMS-LSCE-FFNN product. Negative values (blue) in ΔRMSE and ΔMAE indicate improvement over pCO2model. While positive values (red) in ΔTSS represent an improvement over pCO2model.

The figure represents the changes in RMSE (ΔRMSE, first row), MAE (ΔMAE, second row), and TSS (ΔTSS, third row) between pCIBR_Int (first column) or pCIBR_Clim (second column) and pCO2model while comparing each of them to the OceanSODA product. Negative values (blue) in ΔRMSE and ΔMAE indicate improvement over pCO2model. While positive values (red) in ΔTSS represent an improvement over pCO2model.

Figure (8a and b) demonstrate a significant reduction in RMSE for both pCIBR_Clim and pCIBR_Int compared to the pCO2model. When compared against CMEMS-LSCE-FFNN, a domain-averaged RMSE decrease of approximately 29.48% ± 4.25% is observed for pCIBR_Int, and approximately 37.06% ± 4.46% for pCIBR_Clim, relative to pCO2model. Figure (8c and d) highlight the differences in MAE between the corrected pCO2 datasets and pCO2model, when compared with CMEMS-LSCE-FFNN. For pCIBR_Int, small regions, particularly in the AS, show an increase in MAE. This suggests that the addition of interannually varying pCO2 deviants to pCO2model can lead to a decrease in quality in certain areas. This decline is likely due to the limited temporal frequency of pCO2 cruise observations. In contrast, for pCIBR_Clim, regions with a decline in quality are almost negligible (Fig. 8d). Over the entire IO domain, MAE decreases by approximately 32.19% ± 4.28% for pCIBR_Int and by approximately 38.91% ± 4.93% for pCIBR_Clim. Similarly, Figure (8e and f) show changes in TSS. For pCIBR_Int (Fig. 8e), certain regions exhibit a decrease in TSS. However, for pCIBR_Clim (Fig. 8f), TSS increases consistently across the entire domain. The domain-averaged improvement in TSS is approximately 1.35% ± 0.09% for pCIBR_Int and significantly higher at approximately 5.01% ± 0.21% for pCIBR_Clim. In summary, the results indicate that pCIBR_Clim significantly outperforms pCIBR_Int. It achieves greater reductions in RMSE (37.06% ± 4.46% vs. 29.48% ± 4.25%) and MAE (38.91% ± 4.93% vs. 32.19% ± 4.38%), and a higher improvement in TSS (5.01% ± 0.21% vs. 1.35% ± 0.09%), with fewer regions showing quality degradation. Overall, pCIBR_Clim demonstrates superior performance and consistency when compared against CMEMS-LSCE-FFNN.

Figure 9a and b) illustrate the differences in RMSE between the corrected surface pCO2 data products (pCIBR_Int and pCIBR_Clim) and pCO2model when compared with OceanSODA data. A decrease in RMSE is observed across the domain for both methods. On average, the domain-wide RMSE is reduced by approximately 30.82% ± 4.43% for pCIBR_Int and by approximately 37.73% ± 4.75% for pCIBR_Clim. The differences in MAE are also presented in Fig. 9c and d). Similar to the comparison with CMEMS-LSCE-FFNN, the pCIBR_Int case (Fig. 9c) shows localized increases in MAE, particularly in the AS. In contrast, the MAE decreases consistently across the IO domain for the pCIBR_Clim case (Fig. 9d). On a domain-averaged basis, MAE is reduced by approximately 34.71% ± 4.91% for pCIBR_Int and by approximately 40.94% ± 5.14% for pCIBR_Clim. Figure 9e and f) show TSS improvements. For the pCIBR_Clim case, TSS shows consistent improvement across the IO domain. However, for pCIBR_Int, certain regions exhibit patches of deterioration. On average, the domain-wide TSS improves by approximately 3.81% ± 0.15% for pCIBR_Clim and by approximately 1.00% ± 0.08% for pCIBR_Int. In conclusion, when comparing the two corrected surface pCO2 data products (pCIBR_Int and pCIBR_Clim) with reference to products such as CMEMS-LSCE-FFNN and OceanSODA, pCIBR_Clim demonstrates superior performance. It achieves greater reductions in RMSE and MAE, along with more consistent improvements in TSS, making it the more effective correction method.

Hence, based on this technical analysis, it is evident that both methods (pCIBR_Clim and pCIBR_Int) adopted in this study improve the pCO2model. Furthermore, when compared with other ML-based products, pCIBR_Clim demonstrates superior performance over pCIBR_Int. Nevertheless, we have made both products, i.e., one derived from pCIBR_Int and the other from pCIBR_Clim, available for users. The users can choose the one that best fits the purpose of their research. The corrected surface pCO2 can be utilized to derive more accurate air-sea CO2 flux estimations for the period 1980–2019 in the IO region. This long-term, high-resolution air-sea CO2 flux data can also help identify regions with significant source and sink characteristics within the IO, thereby contributing to a better understanding of the IO’s role in the global carbon budget.

Code availability

The code used to create the final product is available at https://github.com/prasannakanti/XGBoost_pCO2_IO. The study uses Python programming language to execute the machine learning codes.

References

Friedlingstein, P. et al. Global carbon budget 2022. Earth System Science Data Discussions 2022, 1–159 (2022).

Canadell, J. G. et al. Global carbon and other biogeochemical cycles and feedbacks (2021).

Friedlingstein, P. et al. Global carbon budget 2023. Earth System Science Data 15, 5301–5369, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-15-5301-2023 (2023).

Wafar, M., Venkataraman, K., Ingole, B., Ajmal Khan, S. & LokaBharathi, P. State of knowledge of coastal and marine biodiversity of Indian ocean countries. PLoS one 6, e14613 (2011).

Sarma, V. V. S. S. et al. Air-sea fluxes of CO2 in the Indian Ocean between 1985 and 2018: A synthesis based on observation-based surface CO2, hindcast, and atmospheric inversion models. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 37, e2023GB007694 (2023).

Sarma, V. V. S. S. et al. East India coastal current controls the dissolved inorganic carbon in the coastal Bay of Bengal. Marine Chemistry 205, 37–47 (2018).

Chakraborty, K., Valsala, V., Gupta, G. V. M. & Sarma, V. V. S. S. Dominant biological control over upwelling on pco2 in sea east of Sri Lanka. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences 123, 3250–3261 (2018).

Sarma, V. V. S. S., Krishna, M. S. & Srinivas, T. N. R. Sources of organic matter and tracing of nutrient pollution in the coastal Bay of Bengal. Marine Pollution Bulletin 159, 111477 (2020).

Chakraborty, K., Valsala, V., Bhattacharya, T. & Ghosh, J. Seasonal cycle of surface ocean pCO2 and pH in the northern Indian ocean and their controlling factors. Progress in Oceanography 198, 102683 (2021).

Joshi, A. P., Chowdhury, R. R., Warrior, H. V. & Kumar, V. Influence of the freshwater plume dynamics and the barrier layer thickness on the CO2 source and sink characteristics of the Bay of Bengal. Marine Chemistry 236, 104030 (2021).

Sridevi, B. & Sarma, V. Role of river discharge and warming on ocean acidification and pCO2 levels in the Bay of Bengal. Tellus B: Chemical and Physical Meteorology 73, 1–20 (2021).

Joshi, A. P. & Warrior, H. V. Comprehending the role of different mechanisms and drivers affecting the sea-surface pCO2 and the air-sea CO2 fluxes in the Bay of Bengal: A modeling study. Marine Chemistry 243, 104120 (2022).

Joshi, A. P., Ghoshal, P. K., Chakraborty, K. & Sarma, V. V. S. S. Sea-surface pCO2 maps for the Bay of Bengal based on advanced machine learning algorithms. Scientific Data 11, 384 (2024).

Valsala, V. & Maksyutov, S. Interannual variability of the air–sea CO2 flux in the north Indian Ocean. Ocean Dynamics 63, 165–178 (2013).

Valsala, V., Sreeush, M. & Chakraborty, K. The IOD impacts on the Indian Ocean carbon cycle. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 125, e2020JC016485 (2020).

Chakraborty, K. et al. Indian Ocean acidification and its driving mechanisms over the last four decades (1980-2019). Global Biogeochemical Cycles 38, e2024GB008139 (2024).

Chakraborty, K. et al. Mechanisms and drivers controlling spatio-temporal evolution of pCO2 and air-sea CO2 fluxes in the southern Java coastal upwelling system. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 293, 108509 (2023).

Gloege, L., Yan, M., Zheng, T. & McKinley, G. A. Improved quantification of ocean carbon uptake by using machine learning to merge global models and pCO2 data. Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems 14, e2021MS002620 (2022).

Bennington, V., Gloege, L. & McKinley, G. A. Variability in the global ocean carbon sink from 1959 to 2020 by correcting models with observations. Geophysical Research Letters 49, e2022GL098632 (2022).

Gregor, L. & Gruber, N. OceanSODA-ETHZ: A global gridded data set of the surface ocean carbonate system for seasonal to decadal studies of ocean acidification. Earth System Science Data 13, 777–808 (2021).

Chau, T. T. T., Gehlen, M. & Chevallier, F. A seamless ensemble-based reconstruction of surface ocean pCO2 and air–sea CO2 fluxes over the global coastal and open oceans. Biogeosciences 19, 1087–1109 (2022).

Joshi, A. P., Kumar, V. & Warrior, H. V. Modeling the sea-surface pCO2 of the central Bay of Bengal region using machine learning algorithms. Ocean Modelling 178, 102094 (2022).

Chau, T. T. T., Gehlen, M., Metzl, N. & Chevallier, F. CMEMS-LSCE: A global, 0.25°, monthly reconstruction of the surface ocean carbonate system. Earth System Science Data 16, 121–160 (2024).

Gregor, L., Shutler, J. & Gruber, N. High-resolution variability of the ocean carbon sink. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 38, e2024GB008127 (2024).

Bakker, D. C. et al. Surface ocean CO2 atlas database version 2022 (SOCATv2022)(ncei accession 0253659). Earth System Science Data (2022).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. the Journal of machine Learning research 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd acm sigkdd international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining, 785–794 (2016).

Bennington, V., Galjanic, T. & McKinley, G. A. Explicit physical knowledge in machine learning for ocean carbon flux reconstruction: The pCO2-residual method. Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems 14, e2021MS002960 (2022).

Akiba, T., Sano, S., Yanase, T., Ohta, T. & Koyama, M. Optuna: A next-generation hyperparameter optimization framework. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery & data mining, 2623–2631 (2019).

Ghoshal, P. K., Joshi, A. P. & Chakraborty, K. An improved long-term high-resolution surface pCO2 data product for the Indian ocean using machine learning, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14614739 (2025).

Sutton, A. J. et al. A high-frequency atmospheric and seawater pCO2 data set from 14 open-ocean sites using a moored autonomous system. Earth System Science Data 6, 353–366 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their careful reading, constructive comments and helpful suggestions, which have helped us to significantly improve the presentation of this work. The improved version of INCOIS-BIO-ROMS surface pCO2 data products (pCIBR_Clim and pCIBR_Int) has been developed as a part of the ‘Development of Climate Change Advisory Services’ project of the Indian National Centre for Ocean Information Services, Hyderabad, India, under the ‘Deep Ocean Mission’ programme of the Ministry of Earth Sciences (MoES), Govt. of India. The Surface Ocean CO2 Atlas (SOCAT) is an international effort endorsed by the International Ocean Carbon Coordination Project (IOCCP), the Surface Ocean Lower Atmosphere Study (SOLAS), and the Integrated Marine Biosphere Research (IMBeR) program to deliver a uniformly quality-controlled surface ocean CO2 database. The many researchers and funding agencies responsible for collecting data and quality control are thanked for their contributions to SOCAT. Sincere gratitude is extended to the scientists, funding organizations, and SOCAT data collection and quality-control process organizers. The field programs for making ship-based observations (presented in this paper as SAS data) were funded by several Indian funding agencies (Ministry of Earth Sciences, Ministry of Science and Technology, Department of Space) of the Govt. of India. This is INCOIS contribution number 559.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Prasanna Kanti Ghoshal executed the code, analyzed the results, and wrote the original draft. A.P. Joshi aided with conceptualization, developing methodology, designing numerical experiments, and writing the original draft. Kunal Chakraborty was responsible for conceptualizing, analyzing results, writing and editing the original draft, and overall supervision of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ghoshal, P.K., Joshi, A. & Chakraborty, K. An improved long-term high-resolution surface pCO2 data product for the Indian Ocean using machine learning. Sci Data 12, 577 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04914-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04914-z