Abstract

Water quality parameters (pH, dissolved oxygen (DO), total nitrogen (TN, includes both organic nitrogen and inorganic nitrogen), total phosphorus (TP), permanganate index (CODMn), turbidity (Tur), electrical conductivity (EC), and dissolved organic carbon (DOC)) are important to evaluate the ecological health of lakes and reservoirs. In this research, we developed a monthly dataset of these key water quality parameters from 2000 to 2023 for nearly 180,000 lakes and reservoirs across China, using the random forest (RF) models. These RF models took into account the impacts of climate, soil properties, and anthropogenic activities within basins of studied lakes and reservoirs, and effectively captured the spatial and temporal variations of their water quality parameters with correlation coefficients (R2) ranging from 0.65 to 0.76. Interestingly, an increase in Tur and EC was observed during this period, while pH, DO, and other parameters showed minimal fluctuations. This dataset is of significant value for further evaluating the ecological, environmental, and climatic functions of aquatic ecosystems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Lakes and reservoirs are important freshwater resources, and play important roles in climate regulation, ecological function, and environment quality1,2. On the one hand, lakes and reservoirs are crucial for maintaining the health and sustainability of ecosystems3. As key suppliers of drinking water, lakes and reservoirs offer a higher quality and more stable source of freshwater compared to rivers and groundwater4,5. On the other hand, water quality, including pH, dissolved oxygen (DO), dissolved organic carbon (DOC), permanganate index (CODMn), total nitrogen (TN), total phosphorus (TP), turbidity (Tur), and electrical conductivity (EC), controls greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in lakes and reservoirs. Water pH directly influences the dissolubility of carbon dioxide (CO2), and it has been reported that CO2 fluxes in lakes and reservoirs showed a significant negative correlation with pH value6,7. As important substances of CO2 and CH4 production, the content of organic matters, indicated by DOC and CODMn, is generally correlated with the emissions of CO2 and CH47,8. As important nutrients for microbes and algal, TN and TP modulate the activities of photosynthesis, respiration, methanogenesis, nitrification, and denitrification, it has been reported that the contents of TN and TP were positively correlated with CH4 and N2O emissions from lakes and reservoirs6,7,8,9,10. Higher Tur in water can alter light penetration which further affects photosynthetic rates11. EC indicates the contents of dissolved minerals and salts12, which impact water pH and buffering capacity, further modulating gas solubility and emissions13. Therefore, water quality parameters are important predictors for GHG emissions in lakes and reservoirs. However, current monitoring programs are limited to hotspot and sensitive areas, failing to provide a high temporal and spatial resolution picture of above water quality parameters for all the 180,000 lakes and reservoirs across China2,10,14,15,16.

Water quality in lakes and reservoirs is determined by the interactions of climate, soil properties, and anthropogenic activities within their respective watersheds. Global warming intensifies thermal and DO stratification of water bodies, which further modulate the processes of GHG production and consumption5,17,18,19. The increase in atmospheric temperature directly causes water bodies to absorb more heat and increase in water temperature, which leads to the reduction of the saturation solubility of oxygen in water and the decrease in DO concentration20. Torrential rain and strong winds can alter the redox conditions and the surface turbulence of the water body, which further modulates the respiration, methanogenesis, and nitrification-denitrification activities in aquatic ecosystems, as well as the enhancement of water vapor exchange rate at the water surface, thereby accelerating the production and emission of GHG21,22. Soils contain essential nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus, which can be transferred to water bodies through runoff and leaching23. The enrichment of these nutrients in water can lead to eutrophication and associated environmental problems such as algal blooms and oxygen depletion24. Additionally, the pH level of the soil affects the efficiency of plants to absorb and utilize nutrients, when soil pH is out of balance, it can limit the uptake of essential nutrients by plants, leading to nutrient leaching and runoff, which in turn influences water quality25.

Human activities, such as population explosion, the extensive use of nitrogen fertilizers, and land use changes, are important anthropogenic factors controlling water quality parameters in lakes and reservoirs26,27. Changes in land use patterns and vegetation cover alter the content of soil organic matter, as well as its degradation rate, which further controls the lateral transformation of organic carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus from lands to inland waters28,29,30. Compared with cropland, the dissolved organic matter in forest ecosystems is more bioavailable31,32, and even though cropland accounted for only 11.2% of the global terrestrial surface, it contributed more than 50% of the total soil erosion in 201233. Furthermore, the growing population is usually associated with increasing discharge of domestic waste and wastewater, resulting in the overload of organic carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus into nearby lakes and reservoirs27. Agricultural nitrogen fertilization and atmospheric nitrogen deposition are the primary sources of nitrogen pollution in water bodies. Due to the excessive fertilization and low nitrogen utilization, part of nitrogen in cropland directly enters the runoffs and results in agricultural nitrogen non-point source pollution and an increase in nitrogen load in surface water34. The global annual application of nitrogen fertilizer in croplands reached 120 Tg in 2015, but more than half of the applied nitrogen was lost to the environment because the nitrogen utilization efficiency was less than 50%35. Nitrogen deposition has increased twofold over the past 100 years globally and by 60% from 1980 to 2010 in China36. Reactive nitrogen in the form of ammonia (NH3) and nitrogen oxides (NOx) which are mainly from nitrogen fertilizer, livestock cultivation and fossil fuel combustion, deposited in aquatic ecosystems after a series of chemical conversions and physical transport that can alter the biogeochemical cycling and affect the nutrient levels37,38. Above all, climate, soil properties, and anthropogenic activities jointly influence the levels of water quality, and it is promising to use these factors to predict water quality parameters of lakes and reservoirs.

In previous studies, most water quality research has concentrated on the comprehensive determination of the River Water Quality Index (WQI)39,40. This method is particularly helpful for rivers, as it simplifies complex water quality data into an understandable metric for management and policy-making. But, water quality data in lakes and reservoirs are mainly produced by in-situ observation, remote sensing, or mathematical simulations41,42. There are several limitations: (1) most mathematical simulation studies use linear regression models, which makes it challenging to effectively capture the variation of water quality parameters when they are characterized by nonlinearity and randomness43; (2) most studies focus on only the water quality characteristics of specific regions, for instance, the lakes in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River, high resolution nationwide datasets are highly unavailable44,45,46; (3) it is hard to achieve high spatial and temporal resolution water quality datasets due to the huge investment of labor and money required for in-situ observations43; (4) remote sensing is only available to monitor light-sensible parameters, such as DOC and algae contents, but fails to produce national datasets of pH, DO, and EC.

In this study, we aim to produce high resolution datasets of water quality parameters (pH, DO, DOC, CODMn, TN, TP, Tur, and EC) in nearly 180,000 lakes and reservoirs in China from 2000 to 2023. Machine learning was used to interpret the influences of climate, soil properties, and anthropogenic activities on water quality parameters in lakes and reservoirs, and further to produce monthly water quality datasets of the whole country. The results of this study will not only deepen our understanding of how climate, soil properties, and human activities affect the water quality of lakes and reservoirs, but also provide valuable datasets for assessing their impact on greenhouse gas emissions and evaluating the conditions of lakes and reservoirs through the Water Quality Evaluation System47,48.

Methods

Study area

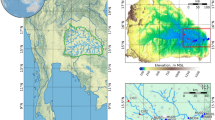

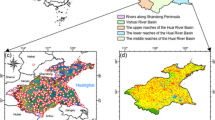

China’s inland water system was divided into 6 regions according to their hydrology, geomorphology, and climate characteristics (Fig. 1), namely Greater Pearl, Yangtze, Huang-Huai-Hai, Northeast China (NE China), Northwest China (NE China), and Tibetan Plateau45. Rivers in different regions influenced the formation, characteristics and ecological health of lakes and reservoirs by influencing water supply, water quality, sediment deposition, and ecological connectivity of water bodies. The Yangtze River and the Pearl River were the first and fourth largest rivers in China respectively, both of which located in the humid and warm subtropical monsoon climate zoon. The Huang-Huai-Hai region included 3 major rivers, namely the Yellow River, the Huaihe River and the Haihe River, which belonged to the semi-arid and semi-humid region. The last three regions were located in northern China and had a relatively dry and cold climate. In general, most of these five areas had low to medium elevations and the terrain was mainly plains, basins and hills while the Tibetan Plateau had a high altitude more than 3000 m and an extremely cold plateau climate49.

Lakes and reservoirs in China were numerous and diverse. The total area of natural lakes was approximately 80,000 km2 and about 2,800 natural lakes with area greater than 1 km2 each, and China currently had nearly 100,000 reservoirs with a total water surface area of about 50,000 km2 (Fig. 1)44,50,51. The distribution density of lakes and reservoirs in the 6 regions varied significantly, influenced primarily by the terrain and climate44. In China, lakes were mostly distributed in NW China, NE China, Tibetan Plateau, and Huang-Huai-Hai regions, while reservoirs in Greater Pearl and Yangtze regions (Fig. 1). The Greater Pearl and Yangtze regions, particularly the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River, had the largest clusters of freshwater lakes and reservoirs in China, and these regions were characterized by a large demand for agricultural irrigation51. By the contrast, lakes on the Tibetan Plateau were mostly densely distributed inland saline lakes fed by mountain snow and glacier meltwater, which were significantly affected by global warming44. The distribution of lakes in NW China was highly uneven with approximately 40% of the lakes concentrated in the area surrounding the Tianshan Mountains, where meltwater from high mountain ice and snow served as a crucial replenishment source52. Lakes in NE China were mainly distributed in plains dominated by agriculture, where there was a significant demand for agricultural irrigation53. Reservoirs in the Huang-Huai-Hai region were mainly located in urban areas and served as the major urban water sources51.

Driving dataset

To predict the water quality of lakes and reservoirs nationwide, we used gridded datasets encompassing climate, soil properties, and anthropogenic activities as input features to build the machine learning model (Table 1). Monthly climate data (including 2 m temperature, precipitation, 10 m wind speed, and surface solar radiation) was from ECMWF Reanalysis v5 (ERA5), with a spatial resolution about 28 km × 28 km54. Annual content of soil organic carbon was obtained from the Global Carbon Budget 2023, with a spatial resolution of about 55 km × 55 km55. Annual land cover data was derived from the China Land Cover Dataset (CLCD), with a spatial resolution of 30 m × 30 m56. Monthly soil respiration data was simulated using Integrated Biosphere Simulator (IBIS) model with a spatial resolution of about 10 km × 10 km57. Soil properties (including soil pH, soil total phosphorus (soil TP), and soil total nitrogen (soil TN)) was obtained from the China High-Resolution National Soil Information Grid Basic Attribute Dataset (2010–2018), with a spatial resolution of 90 m × 90 m58. Monthly Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) data was acquired from The Terra Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) Vegetation Indices (MOD13A3) Version 6, featuring a 1 km × 1 km spatial resolution59. Annual population distribution data was obtained from the LandScan dataset provided by Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL), with a 1 km × 1 km spatial resolution60. Annual nitrogen fertilizer application data was sourced from the global crop-specific nitrogen fertilization dataset, with an approximate spatial resolution of 10 km × 10 km61. Monthly nitrogen deposition data was obtained from the Chemistry Climate Model Initiative (CCMI) (2000–2014), with a spatial resolution of approximately 250 km × 250 km62. For the period 2015–2025, monthly nitrogen deposition data was available at every five years with a spatial resolution of approximately 250 km × 250 km. It was simulated using the GEOS-Chem model63, which incorporated NOx emissions under the SSP3-70 scenario and NH3 emissions under the BAU scenario64,65. We calculated the monthly total nitrogen deposition in the years 2015, 2020, and 2025, and then performed a linear interpolation to derive the monthly total nitrogen deposition dataset for the years 2016–2019 and 2021–2023, and we distributed the total nitrogen deposition into corresponding grid points following the spatial distribution patterns of 2015 and 2020, respectively.

Water quality data

Water quality data for lakes and reservoirs in China including pH, DO, TP, TN, CODMn, Tur, and EC, were sourced 217 national surface water quality automatic monitoring stations managed by the China National Environmental Monitoring Center (CNEMC) (https://www.cnemc.cn/sssj/), among which 127 stations in lakes and 90 in reservoirs (Fig. 1). These data were collected every 4 hours from 00:00 to 24:00 on the monitoring days with a total of 666,836 monitoring records during January 1, 2021, to December 31, 2022. We also obtained 1326 records of DOC observations from 83 lake and reservoir observation stations between October 2017 and June 2022. The spatial geographic information of lakes and reservoirs in China were derived from the China Reservoir Dataset (CRD) and the Global Lakes Dataset (GLAKES), respectively50,51. In total, 82759 lakes and 97414 reservoirs were extracted from GLAKES and CRD. The base map for the watershed division of each lake or reservoir came from HydroBASINS, which contained geometric attributes such as sub-basin area, distance from upstream headwaters and ocean outlets, and coding information for river basin identification and classification66.

Watershed division

The watershed for each lake and reservoir was determined based on geospatial datasets of CRD, GLAKES and HydroBASINS lev12. The CRD integrated geographic coordinates and maximum water surface of existing reservoirs in China from the Georeferenced global Dams And Reservoirs (GeoDAR), the GlObal geOreferenced Database of Dams (GOODD), and the Global Reservoir and Dam (GRanD) datasets51. Overlappings between GLAKES and CRD were removed to avoid double counting. HydroBASINS lev12 dataset encompassed 1.0 million individual sub-basin polygons66, and a complete watershed of each lake or reservoir was scoped by identifying its nearest sub-basin in HydroBASINS lev12, tracing and merging upstream sub-basins based on the HYBAS_ID.

Data processing

Monthly average of pH, DO, CODMn, TN, TP, Tur, and EC from 217 CNEMC stations and DOC from 83 observing stations were calculated, and their latitude and longitude were corrected using the coordinate picker of Google map (https://www.google.com/maps). To assess the impacts of climate, soil properties, and anthropogenic activities on pH, DO, DOC, CODMn, TN, TP, Tur, and EC in lakes and reservoirs, we calculated their inverse distance weighted (IDW) values using the following equations67,68:

Among which, wi represented the weight of grid i within a watershed, p was the weighted index which usually set to 2, and di was the distance between the grid i and its belonged lake or reservoir; x and y denoted the longitude and latitude of the lake or reservoir, respectively, while xi and yi represented the longitude and latitude of grid i, respectively; zi represented the value of climate, soil property, or anthropogenic activity of grid i.

Model construction and verification

Random Forest (RF) was an ensemble learning technique, which could effectively deal with the noise and outliers of input data, and enhanced the performance of predictive models by aggregating the outcomes of multiple decision trees69. In this approach, decision trees were trained on randomly selected subsets of input data using the bootstrap resampling method which ensured the robustness and stability of final RF model and reduced the risk of overfitting70. Therefore, we used RF models to predict the monthly values of pH, DO, DOC, TN, TP, CODMn, Tur and EC in lakes and reservoirs with 16 climate, soil properties, and anthropogenic activities characteristics in their watersheds (Fig. 2). Modelling was performed using the scikit-learn package under a virtual environment (Python 3.11.0).

Flow chart of monthly water quality data production for lakes and reservoirs in China. The abbreviations of the input data name were explained as follows: CSoil, Soil organic carbon; RSoil, Soil respiration rate; Napp, nitrogen application; Ndep, nitrogen deposition; Pop, population; Cropland, Forest, and Grassland, represented the proportion of cropland, forest, and grassland in land use types, respectively.

To capture monthly patterns of water quality parameters, we constructed RF models every month for pH, DO, DOC, TN, TP, CODMn, Tur and EC. However, only one RF model was constructed for DOC in the whole year due to limited DOC observations. We traversed all possible combinations of the 16 climate, soil properties, and anthropogenic activities features, and repeated 100 iterations for each feature combination. 70% of the input data were used for training and 30% were withheld for testing, and datasets were resampled for repeating each iteration to guarantee the stability of the model. RF models for pH, DO, TN, TP, CODMn, Tur and EC were constructed based on the feature combinations with the highest average R2 of 100 iterations.

Observed datasets of pH, DO, TN, TP, CODMn, Tur and EC from 217 CNEMC stations in 2021 were used to train their RF models, and datasets in 2022 were used to evaluate the generalization capability and predictive efficacy of these constructed models. Due to the limited DOC observations, RF model for DOC was trained and evaluated using all the observations from 2017 to 2022. Finally, monthly variations of pH, DO, DOC, TN, TP, CODMn, Tur and EC for lakes and reservoirs in China during 2000 to 2023 were predicted using constructed RF models and calculated IDWs of climate, soil properties, and anthropogenic activities in their watersheds.

Model evaluation index

The determination coefficient (R2), root mean square error (RMSE), and mean absolute error (MAE) were used to evaluate the performance of regression models. The closer the value of R2 to 1, the better the explanatory ability of the model. Both RMSE and MAE were expressed in the same units as the output variables, and the lower the RMSE and MAE, the higher the model prediction accuracy. The equations for these parameters were as follows:

Data Records

The data is available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27626286.v271. They were formatted in CSV files, with each containing the ID number, latitude and longitude coordinates, and the monthly averages of pH, DO, DOC, TN, TP, CODMn, Tur and EC for respective lakes and reservoirs from 2000 to 2023. These files were named according to the water body type and the year and month.

Technical Validation

Model evaluation index

The computation and extraction of various datasets, the coding of machine learning models and the graph rendering of related results were all completed by using the software Visual Studio Code (Version 1.88, Microsoft, United States) and ArcMap (Version 10.8, Esri, United States).

The performance of the RF models for pH, DO, DOC, TN, TP, CODMn, Tur and EC were shown in Table 2. All the RF models show a good performance with high R2, low RMSE and MAE. The average R2 values for all the RF models were higher than 0.64, while RF models for EC stood for the highest R2, followed by DO and pH. The average RMSE and MAE values for all RF models were lower than 4.56 and 3.55, respectively. Among which, RF models for EC showed the lowest RMSE and MAE, followed by TP and pH.

The discrepancy between predicted and observed values of RF models were depicted in Fig. 3, and each subplot contained four quarters of data, except for DOC in which all the data were shown together. Overall, the predictions showed a good agreement with observed values for all the parameters (Fig. 3). Especially, the predicted values of DOC, DO, pH and EC were very close to the observed values, and most of the predictions were tightly distributed around the 1:1 line, which indicated a high accuracy of these model predictions (Fig. 3b–d,h).

Overall, validation using observations from CNEMC stations in 2022 showed that all the of RF models had good stability and generalization ability with RMSE and MAE lower than 1.52 and 1.11, respectively, demonstrating their strong generalization ability.

Monthly variations in water quality parameters

The monthly variations of pH, DO, DOC, TN, TP, CODMn, Tur and EC were showed in Fig. 4. The pH value ranged from 7.7 to 8.2, was slightly higher in June but had little seasonal fluctuation (Fig. 4a). Similar with our results, previous studies also reported that the proliferation of eutrophic algae along with enhanced photosynthesis and respiration can slightly increase the pH value of lakes through impacting the carbonate equilibrium in surface water during the humid season in summer72,73. The DOC concentration increased from 9.2 mg L−1 in January to 13.1 mg L−1 in August, but afterwards declined again to 8.9 mg L−1 in December (Fig. 4b). Similarly, CODMn concentration reached a maximum of 5.1 mg L−1 in September and a minimum of 2.8 mg L−1 in November (Fig. 4e). The seasonal variations of DOC were not only affected by endogenous effects of phytoplankton photosynthesis production and release of DOC, but also by exogenous inputs such as surface runoffs and rivers inflows74. Thus, the DOC concentration increased during the biological growth and rainfall period75,76. Meanwhile, CODMn concentration was positively correlated with water temperature and organic pollutants, the death and degradation of algae in summer was an important potential reason for the increase of CODMn concentration from June to September45. DO concentrations ranged from 7.9 to 10.4 mg L−1, and showed an obvious seasonal fluctuation from January to December (Fig. 4c). Water temperature dominated the monthly variation of DO concentration, which was negatively correlated with water temperature77,78. Tur was significantly higher in summer, reaching 4.4 JTU in July, and the lowest in February at 0.7 JTU, respectively (Fig. 4d). The monthly variation of EC ranged from 0.05 to 0.07 S m−1, with the highest in May and the lowest in December (Fig. 4h). Strong precipitation in summer transferred a significant amount of dissolved ions into lakes and reservoirs through runoffs, which further increased the values of EC12. Simultaneously, the increase in particulate matter carried by runoffs and the disturbance of sediment by wind and current during rainy season led to the increase of Tur in lakes and reservoirs11.

TN concentrations was higher from September to February with a maximum concentration of 2.4 mg L−1 and lower from March to August with a minimum of 1.4 mg L−1 (Fig. 4f). TP concentrations was higher from June to October with a maximum of 0.08 mg L−1, but reached a minimum of 0.03 mg L−1 in December (Fig. 4g). The decrease of TN concentration from April to August was usually related to the dilution of nitrogen accumulation by runoffs and the increase of water temperature, which promoted the denitrification of microorganisms, as well as the growth and propagation of algae that consumed nitrogen27,46. These metabolites of biological activities also changed the pH of water, resulting in increased phosphorus content in the overlying water, which together promoted the release of phosphorus from the sediment46,79.

Spatial profile of water quality parameters

The spatial profiles of water quality in lakes and reservoirs in China significantly differed with each other (Fig. 5). The spatial profile of pH in lakes and reservoirs followed a distinct regional pattern, which increased gradually from southeast to northwest, ranging from 7.2 to 8.7 (Fig. 5a). The concentrations of DOC and CODMn ranged nationally from 5.0 to 26.7 mg L−1 and 1.0 to 7.0 mg L−1, respectively, and they were both relatively higher in Tibetan Plateau, NW China, NE China, and Yangtze regions compared with most areas of Huang-Huai-Hai and Greater Pearl (Fig. 5b,e). By the contrast, DO was relatively lower (7.5 to 8.5 mg L−1) in the Greater Pearl, southern area of Yangte and NW China compared with other regions (8.5 to 10.5 mg L−1) (Fig. 5c). Nationally, Tur ranged from 0 to 5 JTU, while it was generally higher than 3 JTU in the Tibetan Plateau, the eastern part of the Huang-Huai-Hai and Yangtze regions (Fig. 5d). The TN concentrations in the NE China, Huang-Huai-Hai, and the west part of Greater Pearl ranged from 3.0 to 3.8 mg L−1, while usually turned out to be less than 2.5 mg L−1 in NW China, Tibetan Plateau, as well as most parts of Greater Pearl and Yangtze (Fig. 5f). The TP concentration was above 0.09 mg L−1 in most areas of the Tibetan Plateau, the west part of NE China, and the junction of Huang-Huai-Hai and Yangtze regions, while the concentration was less than 0.05 mg L−1 in most other regions (Fig. 5g). The values of EC were more than three times lower in the Yangtze and Greater Pearl (<0.03 S m−1), than those in the other four regions (>0.09 S m−1) (Fig. 5h).

Since most lakes on the Tibetan Plateau were mainly enclosed saline lakes that continuously received pollutants from external sources, and salinity was the dominant factor affecting the abundance and biomass of phytoplankton communities, these waters were prone to the accumulation of nutrients, and salinity was positively linear to organic carbon sources and soluble ion concentrations58,80,81,82,83. These interconnected factors collectively explained the high concentrations of DOC, CODMn, TP, and EC in the lakes of Tibetan Plateau (Fig. 5b,e,g,h). Due to the arid and semi-arid environment formed by the shortage of water resources and the intense evaporation effect of water surface, there were also many saline lakes with internal flow in NW China84. Field observations showed that these saline lakes tended to be highly eutrophic and the average DOC concentration was approximately 5 times compared to freshwater lakes44. Therefore, under the impact of high salinity and organic matter content, NW China showed higher concentrations of DOC, CODMn and EC (Fig. 5b,e,h). In NW China, the northern Huang-Huai-Hai and the western NE China, soils usually contained carbonate or heavy phosphate which was easily lost into the water and further caused the high pH value due to hydrolysis72. Due to the influence of soil characteristics, vegetation cover, and agricultural management activities, water bodies in the agricultural regions of the eastern NE China and the red soil areas of the Yangtze and Greater Pearl exhibited low pH values72,85,86.

Excessive input of nutrients due to human activities increased the risk of eutrophication in lakes and reservoirs. For example, livestock manure discharge and excessive fertilization in NE China and the plain of Huang-Huai-Hai led to high nitrogen emission density and transferred to lakes and reservoirs by leaching and runoffs which increased the TN loads of water bodies24,87. Driven by population growth, urbanization and intensive agricultural production in the junction of Huang-Huai-Hai and Yangtze regions, large amount of nitrogen and phosphorus nutrients were discharged into lakes and reservoirs along with domestic sewage, industrial and agricultural wastewater, resulting in eutrophication with high concentrations of DOC, TN and TP in the water bodies44,79,88. Algal blooms, residual aquatic plant debris, and re-suspended sediments, coupled with the accumulation of feed residues and excrement from aquaculture activities, had collectively led to elevated levels of Tur in the lakes and reservoirs located in the junction of Huang-Huai-Hai and the middle and lower Yangtze regions88,89.

Annual variations in water quality parameters

Fig. 6 presents the annual variations of pH, DO, DOC, TN, TP, CODMn, Tur, and EC in Chinese lakes and reservoirs from 2000 to 2023. From 2000 to 2023, the annual averages of Tur and EC showed significant temporal variations (k = 0.0042, p < 0.05 for Tur; k = -0.0001, p < 0.05 for EC) (Fig. 6d and h). By the contrast, pH declined from 7.99 in 2000 to 7.97 in 2023 with a slope of −0.0015 (p < 0.05) (Fig. 6a). While no significant changes were found for DOC, TN, TP (p > 0.05) (Fig. 6b,f and g).

Anthropogenic discharge was one of the main external factors that caused the change of EC12, e.g. significant amount of dissolved salts was lost from agricultural soils to water bodies due to heavy fertilizer application90. While climate change affected EC values in lakes and reservoirs in two ways: (1) extreme precipitation lead to soil erosion and intensified the input of soluble ions from runoffs; (2) extreme drought increased the concentration of certain ions91,92. The interannual variations of CODMn, TN and TP concentrations of lakes and reservoirs in China decreased slightly from 2000 to 2023, which was consistent with previously reported results93. Excessive application of chemical fertilizers led to soil acidification, which in turn allowed dissolved acidic ions to enter water bodies through surface runoffs and leaching, thereby lowering its pH levels94,95. Diminished atmospheric deposition of NH3 resulted in elevated deposition of acidic compounds, which intensified the occurrence of acid rain and consequently lowered the pH of aquatic environments96. Aquatic plant reduction and algal bloom outbreaks due to increased water temperature, had caused shallow water bodies to transition from clear to turbid states97. Increased extreme precipitation events which rapidly washed out material in watersheds, increased benthic activity and water Tur98. Additionally, anthropogenic activities such as deforestation and reclamation, and urban construction led to soil erosion, which in turn caused an increase in Tur92. Meanwhile, Fig. 7 presents the changes of pH, DOC, DO, Tur, CODMn, TN, TP and EC in lakes and reservoirs in China from 2000 to 2023.

Limitation analysis

In this study we build RF models to interpret influences of climate, soil properties, and anthropogenic activities on water quality parameters (pH, DOC, DO, Tur, CODMn, TN, TP, and EC) in lakes and reservoirs, and further developed monthly dataset of these water quality parameters using these RF models from 2000 to 2023. This dataset offers high resolution and long-term information of environmental characteristics for nearly 180,000 lakes and reservoirs across China, which bridges the current gap between limited observations and keen demand for water quality parameters in aquatic ecosystems. While, some limitations still need to be solved in further studies: (1) long-term high-resolution dataset of soil properties is currently unavailable except for the China High-Resolution National Soil Information Grid Basic Attribute Dataset (2010–2018); (2) fertilizer applications are important anthropogenic activities influencing the water quality in lakes and reservoirs, while currently, they are only available interannually instead of monthly; (3) few CNEMC observation stations are located in Tibetan Plateau, which may limit the accuracy of RF models in this region. In the further, efforts should be made to develop long-term and high temporal resolution datasets of soil properties and fertilizer applications, as well as to build more CNEMC observation stations in Tibetan Plateau, in order to improve the accuracy of predicted values of pH, DOC, DO, Tur, CODMn, TN, TP, and EC in lakes and reservoirs.

Code availability

The code in this study is available from https://github.com/Luanlong/Water-quality.

Change history

30 June 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05431-9

References

Zhao, E., Kuo, Y.M. & Chen, N. Assessment of water quality under various environmental features using a site-specific weighting water quality index. Science of The Total Environment 783, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.146868 (2021).

Zhang, H. et al. Changes in China’s river water quality since 1980: management implications from sustainable development. npj Clean Water 6, 45, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-023-00260-y (2023).

Vasistha, P. & Ganguly, R. Water quality assessment of natural lakes and its importance: An overview. Materials Today: Proceedings 32, 544–552, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.02.092 (2020).

Yang, Y. Antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in global lakes: A review and meta-analysis. Environment International 116, 60–73, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2018.04.011 (2018).

Zhang, Y. Importance and main ecological and environmental problems of lakes in China. Science China Press 67, 3503–3519, https://doi.org/10.1360/TB-2022-0178 (2022).

Schrier-Uijl, A. P., Veraart, A. J., Leffelaar, P. A., Berendse, F. & Veenendaal, E. M. Release of CO2 and CH4 from lakes and drainage ditches in temperate wetlands. Biogeochemistry 102, 265–279, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-010-9440-7 (2011).

Yang, P. & Tong, C. Emission paths and measurement methods for greenhouse gas fluxes from freshwater ecosystems: a review. Acta Ecologica Sinica 35, 6868–6880 https://doi.org/10.5846/stxb201406231298 (in Chinese) (2015).

Huttunen, J. T. Fluxes of methane, carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide in boreal lakes and potential anthropogenic effects on the aquatic greenhouse gas emissions. Chemosphere 52, 609–621, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0045-6535(03)00243-1 (2003).

Clough, T. J., Buckthought, L. E., Casciotti, K. L., Kelliher, F. M. & Jones, P. K. Nitrous Oxide Dynamics in a Braided River System, New Zealand. Journal of Environmental Quality 40, 1532–1541, https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2010.0527 (2011).

Zhou, Y. Improving water quality in China: Environmental investment pays dividends. Water Research 118, 152–159, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2017.04.035 (2017).

Nie, X. Temporal and spatial distribution characteristics of conductivity and turbidity of the lower reaches of Lancang river cascade reservoirs. Journal of China Three Gorges University (Natural Sciences) 43, 18–24 https://doi.org/10.13393/j.cnki.issn.1672-948X.2021.01.004 (in Chinese) (2021).

Wang, R. Temporal and spatial variations in the conductivity in different media in Taihu lake, China. Environmental Science 40, 4469–4477 https://doi.org/10.13227/j.hjkx.201904194 (in Chinese) (2019).

Yang, F. Dissolution and emission patterns and influencing factors of greenhouse gases in Panjiakou Reservoir. China Environmental Science 41, 5303–5313 https://doi.org/10.19674/j.cnki.issn1000-6923.20210513.001 (in Chinese) (2021).

Li, B., Yang, G. & Wan, R. Multidecadal water quality deterioration in the largest freshwater lake in China (Poyang Lake): Implications on eutrophication management. Environmental Pollution 260, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114033 (2020).

Lin, J. et al. An extensive spatiotemporal water quality dataset covering four decades (1980–2022) in China. Earth System Science Data 16, 1137–1149, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-16-1137-2024 (2024).

Zhi, W., Appling, A. P., Golden, H. E., Podgorski, J. & Li, L. Deep learning for water quality. Nature Water 2, 228–241, https://doi.org/10.1038/s44221-024-00202-z (2024).

Woolway, R. I. & Merchant, C. J. Worldwide alteration of lake mixing regimes in response to climate change. Naure Geoscience. 12, 271–276, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-019-0322-x (2019).

Jane, S. F. et al. Widespread deoxygenation of temperate lakes. Nature 594, 66–70, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03550-y (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Dissolved oxygen stratification and response to thermal structure and long-term climate change in a large and deep subtropical reservoir (Lake Qiandaohu, China). Water Research 75, 249–258, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2015.02.052 (2015).

Zhou, J. et al. Controls of thermal response of temperate lakes to atmospheric warming. Nature Communications 14, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-42262-x (2023).

Motew, M., Booth, E. G., Carpenter, S. R., Chen, X. & Kucharik, C. J. The synergistic effect of manure supply and extreme precipitation on surface water quality. Environmental Research Letters 13, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aaade6 (2018).

Zhang, Y. et al. Rainstorm and strong wind weathers largely increase greenhouse gases flux in shallow ponds. Science of The Total Environment 923, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.171478 (2024).

Liu, J., Sævarsson, H. T., Bechmann, M., Krogstad, T. & Øgaard, A. F. Chemical processes and prediction of dissolved phosphorus leaching in mineral and organic soils. Geoderma 445, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2024.116890 (2024).

Zhou, N., Xu, X. & Yuan, Z. Nitrogen and phosphorus concentrations trends and the effects of human activities in China’s 14 typical lakes during 2010 and 2018. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation 36, 281–286, https://doi.org/10.13870/j.cnki.stbcxb.2022.05.034 (2022).

Barrow, N. J. & Hartemink, A. E. The effects of pH on nutrient availability depend on both soils and plants. Plant Soil 487, 21–37, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-023-05960-5 (2023).

Anderson, N. J., Dietz, R. D. & Engstrom, D. R. Land-use change, not climate, controls organic carbon burial in lakes. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 280, 20131278, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2013.1278 (2013).

Ji, X., Wang, S., Yang, K. & Ren, P. Temporal and spatial variation characteristics of total nitrogen concentration in surface water from 2016 to 2020 in China. Ecology and Environment 31, 1184–1192 https://doi.org/10.16258/j.cnki.1674-5906.2022.06.014 (in Chinese) (2022).

Mendonça, R. et al. Organic carbon burial in global lakes and reservoirs. Nature Communications 8, 1694, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-01789-6 (2017).

Kang, W., Hu, X., Feng, R., Wei, C. & Yu, F. DOM Associates with Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Chinese Rivers under Diverse Land Uses. Environmental Science & Technology 57, 15004–15013, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.3c03826 (2023).

Liu, X. D., Qiao, Y. N. & Zhou, G.-Y. Controlling action of soil organic matter on soil moisture retention and its availability: Controlling action of soil organic matter on soil moisture retention and its availability. Chinese Journal of Plant Ecology 35, 1209–1218, https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1258.2011.01209 (2011).

Williams, C. J., Yamashita, Y., Wilson, H. F., Jaffé, R. & Xenopoulos, M. A. Unraveling the role of land use and microbial activity in shaping dissolved organic matter characteristics in stream ecosystems. Limnology & Oceanography 55, 1159–1171, https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2010.55.3.1159 (2010).

Liu, Q. et al. Impact of land use on the DOM composition in different seasons in a subtropical river flowing through a region undergoing rapid urbanization. Journal of Cleaner Production 212, 1224–1231, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.12.030 (2019).

Borrelli, P. et al. An assessment of the global impact of 21st century land use change on soil erosion. Nature Communications 8, 2013, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-02142-7 (2017).

Li, W. et al. Critical processes and major factors that drive nitrogen transport from farmland to surface water bodies. Frontiers of Agricultural Science and Engineering 0, 0, https://doi.org/10.15302/J-FASE-2023518 (2023).

Gu, B. et al. Cost-effective mitigation of nitrogen pollution from global croplands. Nature 613, 77–84, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05481-8 (2023).

Chen, W. et al. Precipitation trend increases the contribution of dry reduced nitrogen deposition. npj Climate and Atmospheric Science 6, 62, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-023-00390-7 (2023).

Jiang, X. et al. Nitrogen concentration response to the decline in atmospheric nitrogen deposition in a hypereutrophic lake. Environmental Pollution 300, 118952, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2022.118952 (2022).

Yu, G. et al. Stabilization of atmospheric nitrogen deposition in China over the past decade. Nature Geoscience 12, 424–429, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-019-0352-4 (2019).

Fulazzaky, M. A. Assessing the suitability of stream water for five different uses and its aquatic environment. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 185, 523–535, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-012-2572-6 (2013).

Fulazzaky, M. A., Seong, T. W. & Masirin, M. I. M. Assessment of Water Quality Status for the Selangor River in Malaysia. Water, Air, and Soil Pollution 205, 63–77, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11270-009-0056-2 (2010).

Wai, K. P., Chia, M. Y., Koo, C. H., Huang, Y. F. & Chong, W. C. Applications of deep learning in water quality management: A state-of-the-art review. Journal of Hydrology 613, 128332, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2022.128332 (2022).

Lian, J., Yan, L., Yao, Y. & Chen, Y. Hydrodynamic and water quality impacts of water transfer project on regulating reservoir, a case study of Dongzhang reservoir. Journal of Hydrology 614, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2022.128494 (2022).

Huan, J. et al. Prediction of CODMn concentration in lakes based on spatiotemporal feature screening and interpretable learning methods - A study of Changdang Lake, China. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 219, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2024.108793 (2024).

Song, K. et al. Dissolved carbon in a large variety of lakes across five limnetic regions in China. Journal of Hydrology 563, 143–154, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2018.05.072 (2018).

Jing, L. et al. Spatiotemporal change analysis of permanganate index in the middle and lower mainstem of the Yangtze River since 2004. Journal of Lake Sciences 33, 1112–1122, https://doi.org/10.18307/2021.0413 (2021).

Yang, Y., Zhu, C., Chen, Y., Zhang, H. & Cui, K. Temporal-spatial distribution characteristics of nitrogen, phosphorus and Chlorophyll a in Chaohu Lake and their correlation with Environmental factors. Guangdong Chemical Industry 51, 87–89, https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1007-1865.2024.02.026 (2024).

Fulazzaky, M. A. Water quality evaluation system to assess the Brantas river water. Water Resources Management 23, 3019–3033, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-009-9421-6 (2009).

Fulazzaky, M. A. Water quality evaluation system to assess the status and the suitability of the Citarum river water to different uses. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 168, 669–684, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-009-1142-z (2010).

Ran, L. et al. Substantial decrease in CO2 emissions from Chinese inland waters due to global change. Nature Communications 12, 1730, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21926-6 (2021).

Pi, X. et al. Mapping global lake dynamics reveals the emerging roles of small lakes. Nature Communications 13, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-33239-3 (2022).

Song, C. et al. A comprehensive geospatial database of nearly 100 000 reservoirs in China. Earth System Science Data 14, 4017–4034, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-14-4017-2022 (2022).

Wang, W., SAMAT, A., Ma, L., Ge, Y. & ABUDUWAILI, J. Spatio-temporal variations and trend analysis of lake area in Xinjiang in 1986-2019. Acta Ecologica Sinica 42, 1300–1314 https://doi.org/10.5846/stxb202101150156 (in Chinese) (2022).

Liu, K. et al. Monitoring Surface Water Change in Northeast China in 1999–2020: Evidence from Satellite Observation and Refined Classification. Chinese Geographical Science 34, 106–117, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11769-024-1411-3 (2024).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 146, 1999–2049, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.3803 (2020).

Friedlingstein, P. et al. Global Carbon Budget 2023. Earth System Science Data 15, 5301–5369, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-15-5301-2023 (2023).

Yang, J. & Huang, X. The 30 m annual land cover dataset and its dynamics in China from 1990 to 2019. Earth System Science Data 13, 3907–3925, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-13-3907-2021 (2021).

Yuan, W. et al. Multiyear precipitation reduction strongly decreases carbon uptake over northern China. JGR Biogeosciences 119, 881–896, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014JG002608 (2014).

Liu, F. et al. Mapping high resolution National Soil Information Grids of China. Science Bulletin 67, 328–340, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scib.2021.10.013 (2022).

Didan, K. MODIS/Terra Vegetation Indices Monthly L3 Global 1km SIN Grid V061 [Data set]. NASA EOSDIS Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center. https://doi.org/10.5067/MODIS/MOD13A3.061 (2021).

Lebakula, V. et al. LandScan Silver Edition. Oak Ridge National Laboratory https://doi.org/10.48690/1531770 (2024).

Adalibieke, W., Cui, X., Cai, H., You, L. & Zhou, F. Global crop-specific nitrogen fertilization dataset in 1961–2020. Scientific Data 10, 617, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-023-02526-z (2023).

Eyring, V et al. Overview of IGAC/SPARC Chemistry-Climate Model Initiative (CCMI) Community Simulations in Support of Upcoming Ozone and Climate Assessments. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:55407008 (2013).

Zhao, Y. et al. Atmospheric nitrogen deposition to China: A model analysis on nitrogen budget and critical load exceedance. Atmospheric Environment 153, 32–40, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2017.01.018 (2017).

O’Neill, B. C. et al. The Scenario Model Intercomparison Project (ScenarioMIP) for CMIP6. Geoscientific Model Development 9, 3461–3482, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-9-3461-2016 (2016).

Zhang, X. et al. Societal benefits of halving agricultural ammonia emissions in China far exceed the abatement costs. Nature Communications 11, 4357, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18196-z (2020).

Lehner, B. & Grill, G. Global river hydrography and network routing: baseline data and new approaches to study the world’s large river systems. Hydrological Processes 27, 2171–2186, https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.9740 (2013).

Zhang, J., Guo, L. & Zhang, X. Effects of interpolation parameters in inverse distance weighted method on DEM accuracy. Journal of Geomatics Science and Technology 29, 51–56, https://doi.org/10.3969/j.ssn.1673-6338.2012.01.013 (2012).

Khouni, I., Louhichi, G. & Ghrabi, A. Use of GIS based Inverse Distance Weighted interpolation to assess surface water quality: Case of Wadi El Bey, Tunisia. Environmental Technology & Innovation 24, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eti.2021.101892 (2021).

Regier, P., Duggan, M., Myers‐Pigg, A. & Ward, N. Effects of random forest modeling decisions on biogeochemical time series predictions. Limnology & Ocean Methods 21, 40–52, https://doi.org/10.1002/lom3.10523 (2023).

Schonlau, M. & Zou, R. Y. The random forest algorithm for statistical learning. The Stata Journal: Promoting communications on statistics and Stata 20, 3–29, https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X20909688 (2020).

Luan, S. et al. High Resolution Water Quality Dataset of Chinese Lakes and Reservoirs from 2000 to 2023. Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27626286.V2 (2025).

Zhang, X. Primary analysis of water pH and salinity monitoring data on Chinese ecosystem research network CERN. Advanced Earth Sciences 24, 1042–1050 (2009).

Luo, Q. The Influence of Algae Metabolism on Dissolved Oxygen and pH in Surface Water. Guangdong Chemical Industry 48, 138–139 (in Chinese) (2021).

Chow, M. et al. Long Term Trends and Dynamics of Dissolved Organic Carbon (DOC) in a Subtropical Reservoir Basin. Water 9, 545, https://doi.org/10.3390/w9070545 (2017).

Kai, J. Seasonal variations of dissolved organic carbon and total nitrogen concentrations in Nam Co and inflowing rivers, Tibet Plateau. Journal of Lake Sciences 31, 1099–1108, https://doi.org/10.18307/2019.0410 (2019).

Chen, X. Spatiotemporal changes and the driving mechanisms of dissolved organic carbon and nitrogen in water in Nantiaoxi river watershed. Acta Scientiae Circumstantiae 254–265, https://doi.org/10.13671/j.hjkxxb.2022.0213 (in Chinese) (2023).

Fu, X., Wu, R., Qi, H. & Yin, H. Long-term trends in surface water quality of China’s seven major basins based on water quality identification index and big data analysis. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 100, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2023.107090 (2023).

Zhang, W., Han, S., Zhang, D. & Shan, B. Recovery in Dissolved Oxygen Levels in Chinese Freshwater Ecosystems in the Past Three Decades. ACS EST Water 2, 967–974, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsestwater.1c00460 (2022).

Ji, P. Spatial-temporal Variations and Driving of Nitrogen and Phosphorus Ratios in Lakes in the Middle and Lower Reaches of Yangtze River. Environmental Science 41, 4030–4041, https://doi.org/10.13227/j.hjkx.202002017 (2020).

Yan, L. Lake water in the Tibet Plateau: Quality change and current status evaluation. Acta Scientiae Circumstantiae 38, 900–910 https://doi.org/10.13671/j.hjkxxb.2017.0390 (in Chinese) (2018).

Liu, G. et al. Remote sensing of CDOM and DOC in alpine lakes across the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau using Sentinel-2A imagery data. Journal of Environmental Management 286, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.112231 (2021).

Huang, W., Zhang, X., Luo, X. & Zhang, L. Main Driving Factors of Eutrophication of Gaoyang Lake in the Three Gorges Reservoir Area: Based on Principal Component Analysis. Ecology and Environmental Monitoring of Three Gorges7, 1–7 https://doi.org/10.19478/j.cnki.2096-2347.2022.01.01 (in Chinese) (2022).

Zhang, Y. Seasonal Variation of Water Quality and Its Influencing Factors in Lake Xingyun. Journal of Water Resources Research 06, 512–521 https://doi.org/10.12677/jwrr.2017.65060 (in Chinese) (2017).

Wen, Z. et al. A national-scale data set for dissolved carbon and its spatial pattern in lakes and reservoirs across China. Scientific Data 7, 82, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-020-0419-5 (2020).

Liu, X. Decadal variations in pH and salinity of waters in typical agro-ecosystems in China. Environmental Chemistry 38, 1214–1222 https://doi.org/10.7524/j.issn.0254-6108.2018081503 (in Chinese) (2019).

Zhao, X. Scientific Issues and Strategies of Acid Soil Use in China. Acta Pedologica Sinica 60, 1248–1263 https://doi.org/10.11766/trxb202307250290 (in Chinese) (2023).

Ma, E. et al. Spatial pattern and water environmental impact of nitrogen and phosphorus emissions from agricultural sources in China in recent 30 years. Journal of Natural Resources 36, 752 https://doi.org/10.31497/zrzyxb.20210316 (in Chinese) (2021).

Zhu, G. Changqing characteristics and driving factors of trophic state of lakes in the middle and lower reaches of Yangtze River in the past 30 years. Journal of Lake Sciences 31, 1510–1524 https://doi.org/10.18307/2019.0622 (in Chinese) (2019).

Wang, J. The potential impact of phosphorus concentration in typical lakes in China on water body indicators and cyanobacteria bloom trends based on meta -analysis. Journal of Beijing University of Chemical Technology 48, 59–67 https://doi.org/10.13543/j.bhxbzr.2021.02.008 (in Chinese) (2021).

Yang, H. Effects of land use on soil moisture, pH and electrical conductivity. Acta Agriculturae Zhejiangensis 28, 1922–1927 https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1004-1524.2016.11.18 (in Chinese) (2016).

Xia, H., Wu, Q. & Mou, X. Advances in impacts of climate change on surface water quality. Advances in Water Science 23, 124–133 https://doi.org/10.14042/j.cnki.32.1309.2012.01.020 (in Chinese) (2012).

Jiang, P. A review on the effects of climate change and human activities on nutrient flux processes in rivers. Journal of Water Resources and Water Engineering 34, 23–44 https://doi.org/10.11705/j.issn.1672-643X.2023.04.04 (in Chinese) (2023).

Jie, X. Assessment and change analysis of national surface water environmental quality in 2011–2021. Environmental Monitoring in China 39, 23–32 https://doi.org/10.19316/j.issn.1002-6002.2023.04.03 (in Chinese) (2023).

Xu, Y. Research Progresses on Soil Acidification and Its Effects on SoilMicroorganism-Crop Systems in Agricultural Soil. Chinese Journal of Soil Science 55, 562–572 https://doi.org/10.19336/j.cnki.trtb.2022100903 (in Chinese) (2024).

Chen, X. et al. How to identify and adopt cleaner strategies to improve the continuous acidification in orchard soils? Journal of Cleaner Production 330, 129826, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.129826 (2022).

Liu, M. et al. Ammonia emission control in China would mitigate haze pollution and nitrogen deposition, but worsen acid rain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116, 7760–7765, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1814880116 (2019).

Zhang, P. et al. Warming alters juvenile carp effects on macrophytes resulting in a shift to turbid conditions in freshwater mesocosms. Journal of Applied Ecology 59, 165–175, https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.14040 (2022).

Rose, K. C., Winslow, L. A., Read, J. S. & Hansen, G. J. A. Climate‐induced warming of lakes can be either amplified or suppressed by trends in water clarity. Limnology and Oceanography Letters 1, 44–53, https://doi.org/10.1002/lol2.10027 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFF0805403), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42203004), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U21A6001), and the Guangdong Major Project of Basic and Applied Basic Research (2020B0301030004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.Y., J.W., S.L. and H.P. conceived and designed the study; H.P., S.L., R.S., X.X. and H.D. participated in data collection; H.P. and S.L. performed the analysis and wrote the paper; J.W. edited and revised the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Luan, S., Pan, H., Shen, R. et al. High Resolution Water Quality Dataset of Chinese Lakes and Reservoirs from 2000 to 2023. Sci Data 12, 572 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04915-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04915-y