Abstract

The characteristics of refractory epilepsy change with disease progression. However, relevant studies are scarce due to the difficulty in obtaining long-term multi-site data from patients with epilepsy. This work aimed to provide a long-term brain electrophysiological dataset of 15 pilocarpine-treated rats with temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE). The dataset was constituted by multi-site local field potential (LFP) signal recorded from 12 sites in the Papez circuit in TLE, including spontaneous seizures and interictal fragments in the chronic period. The LFP data were saved in MATLAB, stored in the Neurodata Without Borders format, and published on the DANDI Archive. We validated the dataset technically through specific signal analysis. In addition, we provided MATLAB codes for basic analyses of this dataset, including power spectral analysis, seizure onset pattern identification, and interictal spike detection. This dataset could reveal how the electrophysiological and epileptic network properties of the brain of rats with chronic TLE changed during epilepsy development, thus help inform the design of adaptive neuromodulation for epilepsy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Epilepsy is a chronic neurological disorder with seizures caused by abnormal electrical activity in the brain1. More than 50 million patients have epilepsy worldwide, with one-third suffering from refractory epilepsy2. Patients with refractory epilepsy are resistant to anti-epileptic drugs, implying that the seizures cannot be controlled with drug treatment3. Nowadays, a large number of studies are trying to reveal the pathogenesis of epilepsy by studying the related circuits in the brain4,5. The limbic circuit of Papez, which is closely associated with cognitive function, correlates with the generation and propagation of temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE)6. Previous studies have confirmed that the pathological changes in multiple nodes in the Papez circuit lead to TLE7. Meanwhile, epilepsy is a progressive disease8, which means that certain brain structures and functional networks change during the development of the disease9. However, both clinical studies and animal experiments conducted so far have lacked long-term tracking of changes in epilepsy characteristics.

In fact, brain electrophysiological recording is the accepted gold-standard for seizures detection. It is also important for the diagnosis and treatment of epilepsy10. Neuromodulation has been increasingly applied to the treatment of refractory epilepsy in recent years11. Three neuromodulation therapies have been clinically approved: vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), deep brain stimulation (DBS) of the anterior nucleus of the thalamus, and responsive neurostimulation (RNS)11. Both VNS and DBS are open-loop technologies, delivering periodic and continuous electrical stimulation with the preset parameters12,13. RNS is the only device capable of providing closed-loop stimulation by monitoring specific epilepsy characteristics in real time. Also, its effect on seizure control has been widely recognized in clinical practice14,15. However, obtaining long-term multi-site human brain electrophysiological data by using RNS is still difficult due to its limited recording channel sites and short storage time16. Thus, the data from animals such as rats show its unique value.

Considering the present research status, long-term electrophysiological acquisition of the spontaneous chronic epileptic animal model is of great significance. In our previous study, the pilocarpine-treated TLE rat model with spontaneous chronic seizures was used due to its similarity to patients with TLE in terms of histopathological changes and seizure symptoms17,18. We showed that the seizure onset zone (SOZ), the seizure onset pattern (SOP), and the functional network connectivity changed during the development of spontaneous epilepsy in rats with chronic TLE19. A large amount of data were obtained in our research, but there are still many features, especially during the interictal period, have not yet been extracted and are worthy of further analysis. Meanwhile, studies exploring the long-term spatiotemporal changes in local field potential (LFP) signals in rats with chronic epilepsy are limited.

Here we provided a long-term multi-site brain electrophysiological dataset of spontaneous seizures in rats with chronic TLE. The dataset contained 15 pilocarpine-treated rats with TLE. Twelve depth electrodes were implanted in the bilateral subiculum, dentate gyrus, CA1 subfield of the hippocampus, CA3 subfield of the hippocampus, amygdala, and anterior nucleus of thalamus (Papez circuit) in each rat. Continuous LFP data was acquired using the electrodes and the recording module 24 h/day over 2-4 months. As mentioned earlier, the characteristics of spontaneous seizures in rats with chronic TLE changed over time after modeling. Therefore, the obtained data were divided into early and late stages according to the temporal distribution of seizures in each rat. All spontaneous generalized seizures of the rats were extracted from these two stages. Seizure onset at each site was identified through visual inspection.

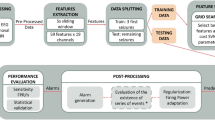

All the data collected by our signal acquisition devices were converted into .mat format in MATLAB, exported as Neurodata Without Borders (NWB) files through MatNWB API, and published in the DANDI Archive. NWB, a highly readable and standardized format, can store all neurophysiological data and metadata for the experiment20. In addition, several useful tools and mature platforms were provided for NWB data processing, analysis, visualization, and sharing21. In this work, we provided MATLAB codes for power spectral analysis, SOP identification, and interictal spike detection. In our previous work, we provided a method for brain network connectivity analysis based on the Granger causality method to evaluate the brain state19. The dataset can be reused to further reveal the alterations in brain electrophysiological properties of the seizure onset and the interictal period with epilepsy progression. The long-term multi-site data is of guiding significance for the study of epilepsy pathological mechanisms and the design of neuromodulation strategies.

Methods

Animals

Fifteen Sprague-Dawley rats (male, weighing 250-350g) were used in this dataset. The rats were housed at Animal Management Center of Zhejiang University standardly before seizure induction. After the lithium-pilocarpine treatment and electrode implantation, all rats were housed separately in the experimental chamber, which enabled experimenters to observe behavior and record LFP signals conveniently. All rats were housed under a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle, with food and water available ad libitum. All experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Zhejiang University (ZJU20190116; Zhejiang University 15896).

Lithium-pilocarpine treatment

The TLE rat model was established by lithium-pilocarpine treatment, which is commonly used to induce spontaneous chronic seizures22,23. First, the rats were injected with lithium chloride (127 mg/kg, i.p., 19-24 h before pilocarpine administration) to reduce pilocarpine dosage and mortality24. Moreover, we used atropine sulfate (1 mL, i.p., 30 min before pilocarpine administration) to reduce saliva secretion25. Then the rats were treated with pilocarpine (32 mg/kg, i.p.), followed by repeated injections of additional half doses of pilocarpine (16 mg/kg, i.p.) every 30 min until status epilepticus (SE) occurred. The seizures during SE must be assessed as grade 5 according to the Racine scale, characterized by rearing and falling26. SE was terminated by administering diazepam (10 mg/kg, i.p.) in 90 min.

Implantation of the depth electrode

The rats were implanted with electrodes under anesthesia (propofol injected, 8 mg/kg, i.p.) 1 month after spontaneous epilepsy induction. In this study, the depth electrodes made of 65 μm Teflon-coated nichrome microfilaments were implanted according to The Rat Brain atlas of Paxinos and Waston27 for recording LFP signals, as shown in Fig. 1a. The electrode was made of two strands, one of which was used to record and the other was used to support and increase the stiffness, ensuring that the electrode could be inserted into the brain tissue without displacement. The rats were fixed on the stereotaxic apparatus, followed by the implantation of 12 depth electrodes in the bilateral subiculum (SUB, AP: -6.0 mm, ML: ± 3.0 mm, DV: -2.5 mm), dentate gyrus (DG, AP: -5.0 mm, ML: ± 3.2 mm, DV: -3.2 mm), CA1 subfield of the hippocampus (CA1, AP: -4.2 mm, ML: ± 3.0 mm, DV: -2.2 mm), CA3 subfield of the hippocampus (CA3, AP: -3.7 mm, ML: ± 4.0 mm, DV: -2.8 mm), amygdala (AMD, AP: -2.4 mm, ML: ± 4.8 mm, DV: -8.0 mm), and anterior nucleus of thalamus (ANT, AP: -1.2 mm, ML: ± 2.0 mm, DV: -5.6 mm), which are part of the circuit of Papez in TLE7 (Fig. 1b). A stainless-steel skull screw was placed in the lambda of the rat skull, with the ground wire winding on. Another stainless-steel skull screw was placed over the left front of the bregma of the rat skull, with the silver reference wire winding on. Since the electrode implantation of all sites, the reference and ground were ready, the electrodes were welded to the connectors, which were used as the interfaces for the electrodes and fixed on the rat skull with dental cement (Fig. 1c).

Data acquisition and selection

LFP signals were continuously recorded 24 h/day in rats with chronic TLE 1 week after the electrode implantation. The data were acquired using the recording module (RHD2132; Intan Technologies, USA) of a multi-site closed-loop neurostimulator designed by our own team28, and multi-site LFP signals were saved in SD cards. As shown in Fig. 1c, the data acquisition was conducted inside an experimental behavior cylinder, with free access to food and water. The bracket fixed on the cylinder was used to attach the battery and the neurostimulator, which was connected to the connector on the rat head via an acquisition cable. Additionally, a conductive slip ring was used to accommodate the free movement of the rats. The LFP signals were amplified and digitized at a sampling frequency of 1 kHz, using a 0.1-500 Hz band-pass filter and a 50 Hz notch filter.

A total of 15 rats were included in the dataset because they had been recorded for more than 6 weeks (86.7 ± 15.4 days) and had more than 12 spontaneous seizures (130.4 ± 115.8 seizures). All seizures detected in the study were confirmed to be generalized seizures with the duration of more than 30 seconds, where ictal activity initiated at some sites within and rapidly spread to bilateral brain regions. Early and late stages were selected for each rat to standardize the dataset and highlight temporal changes in spontaneous epileptic features. Both stages were selected as the week with the most frequent and concentrated seizures, following our own established criterion of more than 4 spontaneous generalized seizures (duration ≥30 s) within 7 days. The early stage was defined as the earliest period that met the criterion after recording, and at least a 1.5-month interval was required between the two stages. Since the seizure onset time and the number of seizures varied from rat to rat, the stage selection differed, as shown in Fig. 2.

An exception was that the interval between the two stages of rat C13 was only 1 month since its total recording duration was shorter than that of most rats due to the headset loss. The generalized seizures with the duration of less than 30 seconds were regarded as minor epileptic seizures, and were also included in this dataset with the suffix “-small”. The interval between the early stage and the late stage was 57.7 ± 12.7 days, based on the statistical analysis of stage selection from the dataset.

All the days with seizures during the selected stages were included in the dataset. A visual inspection of the preprocessed LFP signals was performed by two independent experienced researchers, and the seizure onset time was determined once both reached a consensus. Fragments with a duration of 10 min were extracted around the seizures in both early and late stages, and stored in the dataset. Besides, 2 days without seizures in both stages were included, where two interictal fragments with a duration of 10 min were selected at least 90 min away from each other. We ensured that all the selected fragments were free of severe motion artifacts and noises.

Data Records

All data were converted into NWB files and released on the DANDI Archive (https://doi.org/10.48324/dandi.001044/0.240905.0159)29, which is supported by the BRAIN Initiative for publishing and sharing neurophysiology data. The dataset comprise several NWB files in the directory of each subject, and the number depends on the selection of the early and late stages mentioned above. All days with ictal activity and 2 days without seizures were included in both stages. Thus, each day corresponds to an NWB file named “sub-[Subject ID]_ses-[Experiment date]-[Number of seizures]_ecephys”, including 10-min ictal or interictal fragments shown in Fig. 3. The dataset contains 162 NWB files (102 days with seizures and 60 days without seizures), including 717 ictal fragments, 38 small ictal fragments and 120 interictal fragments. The summed recording duration is 145.8 h (875 × 10 min = 8750 min) and the size is 17.9 GB in total.

Structure of the dataset. (a) Structure of the whole dataset organized in the DANDI Archive. The directories of 15 subjects (sub-Rat**) contain several days of recording data (*.nwb) in both early and late stages from the rats. (b) Example LFP signal trace of 12 channels, including bilateral SUB, DG, CA1, CA3, AMD, and ANT. The middle part of the trace indicates an epileptic seizure.

The NWB files complying with the NWB:N standard (NWB version 2.6.0) provide a standardized way to store and share neurophysiological data30. Each file contains all structured and unstructured metadata of the experiment, which can be easily read using the PyNWB API for Python or the MatNWB API for MATLAB.

Structure of the NWB File

As a type of HDF5 file, NWB is a highly structured file format, in which the data are organized similarly to a folder hierarchy. An NWB file typically comprises different groups depending on the type of data, such as “acquisition” for unprocessed raw data, “general” for metadata of the experiment, “intervals” for information about the trails, “stimulus” for stimuli used in the experiment, and “units” for single neurons obtained after spike sorting. Notably, “acquisition” and “general” are the main containers that were chosen as the root directories of the NWB files in the dataset, as shown in Fig. 4. Certain fundamental metadata fields were selected specifically to describe basic information about the dataset, such as “session ID”, “institution”, “identifier”, “session start”, “file creation”, etc. A “description” field was designed for each container to provide necessary details and additional information about the data.

NWB file content: acquisition group

The \acquisition group contains the raw data stream obtained from multi-site LFP signal recording in rats with TLE. The subgroups of acquisition\ictal_events and acquisition\interictal_events contain the steams of all the seizure fragments and two interictal fragments respectively. The subgroups are named “[Subject ID]_[Experiment date]-[ictal/small/non]” and sorted in order (“ictal” for the seizure fragment, “small” for the minor seizure that does not stand up to the standard, “non” for the interictal fragment). The “data” in each subgroup is a two-dimensional matrix in the size of 600000 × 12, corresponding to a raw LFP signal (sampling rate: 1 kHz, duration: 10 min, unit: microvolt). All the data in the subgroups are compressed at level 4, with a compression ratio of 3.643:1.

NWB File content: general group

The \general group contains metadata about the experiment. For the basic metadata mentioned earlier, “institution” and “session_id” are stored directly at the top level of \general. Several subgroups are included in the \general group. The general\devices subgroup provides information about the signal acquisition device, which is the depth electrode and the recording module of a multi-site closed-loop neurostimulator made by our team. This subgroup is linked to every electrode channel named after the brain region in the general\extracellular_ephys. The general\extracellular_ephys\electrodes subgroup contains information about all 12 electrodes for multi-site LFP signal recording, including their group names, electrode ID, labels, and locations. For example, the “L_CA1” electrode (ID: 02) is located in the CA1 subfield of the hippocampus in the left hemisphere, with the MNI coordinates (AP: -4.2 mm, ML: -3.0 mm, DV: -2.2 mm). Finally, the metadata of the experimental rats are stored in the general\subject subgroup, such as age, sex, species, weight, and subject ID.

Technical Validation

Power spectral analysis of LFP signal

Power spectral density (PSD) of the LFP signal was calculated to validate both seizures and interictal data technically. We used rat B6 as an example and selected the CA3 subfield of the hippocampus in the left hemisphere for analysis. LFP signal with a duration of 5 s after the seizure onset and within the interictal period were analyzed (Fig. 5a). No signal preprocessing was required because the low-frequency components and 50 Hz noise had already been filtered out by the hardware. The Welch method was used to calculate the PSD of the LFP signal in Matlab (“pwelch” function, with 1.024 s Hamming window and 50% overlap). As shown in Fig. 5b, the low-frequency band PSD during the ictal periods is substantially higher during interictal periods, which is consistent with the brain electrophysiological characteristics during seizures. The PSD in the late stage also changed compared with that in the early stage.

Power spectral analysis. (a) Example ictal and interictal LFP signals of rat B6 (CA3 subfield of the hippocampus) in early and late stages. The red dotted lines mark the seizure onset time identified by visual inspection, and the 5-s window in blue was used for power spectral analysis of ictal and interictal periods. (b) Average LFP power spectral density comparison among the ictal and interictal fragments of rat B6 (CA3 subfield of the hippocampus) in early and late stages. Values are represented as mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.).

Identification of seizure onset

As mentioned above, the seizure onset time for each channel was identified by visual inspection, and then the SOZ (the site with the earliest seizure onset) could be determined. As shown in Fig. 6, the earliest and the latest seizure onsets were marked, and the latency of the seizure onset was calculated. Taking rat E2 as an example, the seizure onset tended to initiate in the bilateral AMD first in the early stage, but initiate in the CA1 subfield of the hippocampus in the late stage. In the meantime, the latency of the seizure onset was considerably reduced during the development of TLE in rat E2.

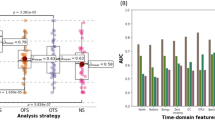

Seizure onset pattern analysis

The SOP was defined as the onset pattern of the SOZ. The SOP was determined by the LFP signal waveform and time-spectrum analysis of the seizure onset. Figure 7 lists four typical SOPs of the epilepsy fragments in the dataset:

(1) Low-voltage fast activity (LVFA), dominated by fast oscillations with low voltage and frequency >13 Hz; the amplitude does not change significantly from the baseline level at the seizure onset (Fig. 7a).

(2) Rhythmic spikes, or spike waves, with low frequency (4-18 Hz) and high amplitude (Fig. 7b).

(3) Theta/alpha sharp activity, characterized by low-frequency (6-11 Hz) sinusoidal activity, whose initial amplitude is higher than that of the LVFA and increases gradually (Fig. 7c).

(4) Beta/gamma sharp activity, characterized by the beta/gamma band sinusoidal activity, whose initial amplitude is higher than that of the LVFA and increases gradually (Fig. 7d).

SOP is one of the most important indicators in the early warning of epilepsy and the prognosis of epilepsy surgery, and helps understand the pathological mechanism of epilepsy31,32. Figure 7e and f show the changes in the proportion of seizure onset patterns in the early and late stages of all individual rats.

Interictal spike detection

Besides seizure fragments, the dataset also involved many interictal fragments, which contained a wealth of valuable information. Interictal spike (IIS), one of the recognized electrophysiological markers of epilepsy, was found between the ictal periods. An independent IIS test was performed on each channel. Figure 8 shows the IIS test result of rat C3 in the early and late stages. The asterisks represent the detected IIS peaks (peak width <100 ms, peak value >5 standard deviations above the baseline), and the interval between the peaks should be >200 ms. More interictal spikes were detected in the late stage than in the early stage. In fact, both IIS in the interictal period and seizures in the ictal period were caused by neuronal depolarization and sustained discharges of the action potential, although the duration differed33. Therefore, it is supposed that they may have similar cellular and pathological mechanisms34. In terms of diagnosing and treating epilepsy, the distribution of IIS can help locate epileptic lesions, and its firing rate can serve as a biomarker for the severity of epilepsy35,36.

Usage Notes

We provided long-term recordings of multi-site LFP signals with spontaneous chronic seizures in rats with TLE, which were stored in NWB files. After downloading them from the DANDI Archive to the local computer, epileptic seizures and interictal data can be imported using PyNWB and MatNWB APIs20,30. We also provided users with the sample code for importing data from NWB files through MatNWB and PyNWB APIs. Figure 9 shows how to read and plot the data of a seizure fragment (raw LFP data, entire 10 min, all 12 channels) of rat B6 with MatNWB and PyNWB.

The resolution of the LFP signals collected from the recording module is 0.195 μV. We had already converted the data into the correct amplitude. Therefore, the LFP signals were measured in microvolts and could be used for direct processing and analysis.

Code availability

The MATLAB scripts used for the NWB file conversion, technical validation and epilepsy feature extraction are available on GitHub (https://github.com/SancTUARYY/epilepsy-analysis).

References

Fisher, R. S. et al. Epileptic seizures and epilepsy: definitions proposed by the international league against epilepsy (ilae) and the international bureau for epilepsy (ibe). Epilepsia 46, 470–472, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0013-9580.2005.66104.x (2005).

Beghi, E. et al. Global, regional, and national burden of epilepsy, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. The Lancet Neurology 18, 357–375, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30454-X (2019).

Kwan, P. et al. Definition of drug resistant epilepsy: consensus proposal by the ad hoc task force of the ilae commission on therapeutic strategies, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02397.x (2010).

Bertram, E. H. Neuronal circuits in epilepsy: do they matter? Experimental neurology 244, 67–74, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.01.028 (2013).

Goldberg, E. M. & Coulter, D. A. Mechanisms of epileptogenesis: a convergence on neural circuit dysfunction. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 14, 337–349, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3482 (2013).

Oikawa, H., Sasaki, M., Tamakawa, Y. & Kamei, A. The circuit of papez in mesial temporal sclerosis: Mri. Neuroradiology 43, 205–210, https://doi.org/10.1007/s002340000463 (2001).

Laxpati, N. G., Kasoff, W. S. & Gross, R. E. Deep brain stimulation for the treatment of epilepsy: circuits, targets, and trials. Neurotherapeutics 11, 508–526, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-014-0279-9 (2014).

Pitkänen, A. & Sutula, T. P. Is epilepsy a progressive disorder? prospects for new therapeutic approaches in temporal-lobe epilepsy. The Lancet Neurology 1, 173–181, https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(02)00073-x (2002).

Kim, H. et al. Structural and functional alterations at pre-epileptic stage are closely associated with epileptogenesis in pilocarpine-induced epilepsy model. Experimental neurobiology 26, 287, https://doi.org/10.5607/en.2017.26.5.287 (2017).

Elger, C. E. & Hoppe, C. Diagnostic challenges in epilepsy: seizure under-reporting and seizure detection. The Lancet Neurology 17, 279–288, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30038-3 (2018).

Ryvlin, P., Rheims, S., Hirsch, L. J., Sokolov, A. & Jehi, L. Neuromodulation in epilepsy: state-of-the-art approved therapies. The Lancet Neurology 20, 1038–1047, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00300-8 (2021).

Englot, D. J., Chang, E. F. & Auguste, K. I. Vagus nerve stimulation for epilepsy: a meta-analysis of efficacy and predictors of response: a review. Journal of neurosurgery 115, 1248–1255, https://doi.org/10.3171/2011.7.JNS11977 (2011).

Fisher, R. et al. Electrical stimulation of the anterior nucleus of thalamus for treatment of refractory epilepsy. Epilepsia 51, 899–908, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02536.x (2010).

Heck, C. N. et al. Two-year seizure reduction in adults with medically intractable partial onset epilepsy treated with responsive neurostimulation: final results of the rns system pivotal trial. Epilepsia 55, 432–441, https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.12534 (2014).

Nair, D. R. et al. Nine-year prospective efficacy and safety of brain-responsive neurostimulation for focal epilepsy. Neurology 95, e1244–e1256, https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000010154 (2020).

Skarpaas, T. L., Jarosiewicz, B. & Morrell, M. J. Brain-responsive neurostimulation for epilepsy (rns® system). Epilepsy research 153, 68–70, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2019.02.003 (2019).

Kandratavicius, L. et al. Animal models of epilepsy: use and limitations. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment 1693–1705, https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S50371 (2014).

Lévesque, M., Avoli, M. & Bernard, C. Animal models of temporal lobe epilepsy following systemic chemoconvulsant administration. Journal of neuroscience methods 260, 45–52, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2015.03.009 (2016).

Yang, Y., Zhang, F., Gao, X., Feng, L. & Xu, K. Progressive alterations in electrophysiological and epileptic network properties during the development of temporal lobe epilepsy in rats. Epilepsy & Behavior 141, 109120, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2023.109120 (2023).

Rübel, O. et al. The neurodata without borders ecosystem for neurophysiological data science. Elife 11, e78362, https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.78362 (2022).

Magland, J., Soules, J., Baker, C. & Dichter, B. Neurosift: Dandi exploration and nwb visualization in the browser. Journal of Open Source Software 9, 6590, https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.06590 (2024).

Curia, G., Longo, D., Biagini, G., Jones, R. S. & Avoli, M. The pilocarpine model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Journal of neuroscience methods 172, 143–157, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.04.019 (2008).

André, V. et al. Pathogenesis and pharmacology of epilepsy in the lithium-pilocarpine model. Epilepsia 48, 41–47, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01288.x (2007).

Marchi, N. et al. Antagonism of peripheral inflammation reduces the severity of status epilepticus. Neurobiology of disease 33, 171–181, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2008.10.002 (2009).

Zhang, F. et al. Efficacy of different strategies of responsive neurostimulation on seizure control and their association with acute neurophysiological effects in rats. Epilepsy & Behavior 143, 109212, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2023.109212 (2023).

Racine, R. J. Modification of seizure activity by electrical stimulation: Ii. motor seizure. Electroencephalography and clinical neurophysiology 32, 281–294, https://doi.org/10.1016/0013-4694(72)90177-0 (1972).

Paxinos, G. & Watson, C.The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates: hard cover edition (Elsevier, 2006).

Zheng, Y. et al. Acute seizure control efficacy of multi-site closed-loop stimulation in a temporal lobe seizure model. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 27, 419–428, https://doi.org/10.1109/TNSRE.2019.2894746 (2019).

Haoqi, N. et al. Dataset of long-term multi-site lfp activity with spontaneous chronic seizures recorded in temporal lobe epilepsy rats, https://doi.org/10.48324/dandi.001044/0.240905.0159 (2024).

Rübel, O. et al. Nwb: N 2.0: an accessible data standard for neurophysiology. BioRxiv 523035, https://doi.org/10.1101/523035 (2019).

Makaram, N., von Ellenrieder, N., Tanaka, H. & Gotman, J. Automated classification of five seizure onset patterns from intracranial electroencephalogram signals. Clinical Neurophysiology 131, 1210–1218, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2020.02.011 (2020).

Lagarde, S. et al. The repertoire of seizure onset patterns in human focal epilepsies: determinants and prognostic values. Epilepsia 60, 85–95, https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.14604 (2019).

Lopantsev, V. & Avoli, M. Participation of gabaa-mediated inhibition in ictallike discharges in the rat entorhinal cortex. Journal of neurophysiology 79, 352–360, https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.1998.79.1.352 (1998).

Lai, N., Li, Z., Xu, C., Wang, Y. & Chen, Z. Diverse nature of interictal oscillations: Eeg-based biomarkers in epilepsy. Neurobiology of Disease 177, 105999, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2023.105999 (2023).

Reynolds, A. et al. Prognostic interictal electroencephalographic biomarkers and models to assess antiseizure medication efficacy for clinical practice: a scoping review. Epilepsia 64, 1125–1174, https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.17548 (2023).

Conrad, E. C. et al. Spatial distribution of interictal spikes fluctuates over time and localizes seizure onset. Brain 143, 554–569, https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awz386 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by STI 2030-Major Projects (2021ZD0200405), National Natural Science Foundation of China (82272112), Outstanding Youth Program of Zhejiang Natural Science Foundation (LR23H180002), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2021KYY600403-0001), the Starry Night Science Fund of Zhejiang University Shanghai Institute for Advanced Study (SN-ZJU-SIAS-002), and 5510 Project of the second affliated hospital of zhejiang university school of medicine. The funders had no role in the design or analysis of the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Junming Zhu and Kedi Xu designed the experiments. Yufang Yang, Fang Zhang, Yongte Zheng, Yuting Sun and Haoqi Ni conducted the experiments. Yongte Zheng and Fang Zhang designed the neurostimulator. Yufang Yang, Haoqi Ni and Yuting Sun performed data analysis. Haoqi Ni standardized and transformed the raw data into the dataset. Haoqi Ni and Kedi Xu wrote the manuscript. All of the authors reviewed the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ni, H., Yang, Y., Zhang, F. et al. Dataset of long-term multi-site LFP activity with spontaneous chronic seizures in temporal lobe epilepsy rats. Sci Data 12, 709 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05023-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05023-7