Abstract

Due to scarcity of data and complex hydrological conditions in the Tianshan region, long-term and complete streamflow data are lacking. This study produced a multi-basin streamflow dataset, named Tianshan watershed streamflow (TSWS) dataset, by comparing the results of Hydrologiska Byråns Vattenavdelning and Long Short-Term Memory models, and analyzed spatiotemporal variation of streamflow.TSWS dataset provides daily streamflow data for 56 watersheds and monthly streamflow data for 89 watersheds in the Tianshan Mountains in 1901–2019. The streamflow simulations of 40 watersheds (daily scale) and 70 watersheds (monthly scale) passed the S-tests (Nash-Sutcliffe efficiency ≥0.5, percent bias ≤25%, and ratio of the root-mean-square error to the standard deviation of measured data ≤0.7). The dataset showed an overall increasing trend of streamflow, especially from 1990 to 2019; spatially, it showed higher streamflow in the west and south, and lower streamflow in the east and north. The dataset provides the first comprehensive simulation and its long time series will provide an important reference for climatic and hydrological studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Lack of financial resources and barriers to data access have led to the current lack of data on river streamflow1,2, especially in high-altitude or high-latitude areas. With the launch of the Global Runoff Data Centre (GRDC)3, more research institutes and researchers are focusing on monitoring and missing streamflow data2. However, the results of previous studies showed that streamflow is not monitored in many river watersheds worldwide4, and the number of monitoring instruments in river watersheds with monitoring hydrological stations is decreasing5,6,7,8. Therefore, the availability and completeness of river runoff data remains a focus of current water resources research.

The modelling and reconstruction of streamflow databases have received widespread attention in recent years9, with a corresponding call from the International Association of Hydrological Sciences (IAHS) for predictions for ungauged basins (PUB)3. Researchers have also developed advanced data acquisition and modelling methods1,10, and model development has shown continuity and diversity11. Examples include the SHETRAN12, WaterGAP213, SWAT14,15, and Hydrologiska Byråns Vattenavdelning (HBV) models16,17. Most researchers are focusing on model improvement and evaluation to better simulate and produce complete time series of river streamflow data suitable for regional studies18,19,20.

With the development and application of computer and machine learning techniques, their ability to deal with non-linearities and non-stationarity has been gradually applied to the modelling of river flows6,21,22. The Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) model achieves an accurate simulation by learning the long-term correlation between input and output data provided23. In addition, Fan et al.24, Hu et al.25, Kratzert et al.23, and Van et al.22 demonstrated that the LSTM performs better than conceptual and physically based traditional hydrological models in simulating rainfall streamflow, highlighting the great potential of the LSTM in large-scale streamflow simulations.

The Tianshan region, the Central Asian Water Tower (CAWT)26, is the source zone of Central Asian rivers and provides water resources for ecological protection and economic development in semi-arid regions27. The results of previous studies revealed a continuous increase in river streamflow in most areas of Tianshan Mountains since 196026,28. Hydrological modelling and machine learning techniques have been extensively explored to simulate hydrological data in the Tianshan Mountains. Yang and Bai26 improved the HBV model to quantify the effects of different streamflow components in the Manas River Basin. Liang et al.29 confirmed that the LSTM simulates flow better than hydrological and other machine-learning models in the Kaidu River Basin. Daily streamflow data are important indicators of hydrological climate change in Central Asia30, and the reliable simulation results of models such as HBV and LSTM will provide data support for the study of streamflow changes in CAWT. However, there are several challenges in streamflow simulation in the Tianshan Mountains at present:

-

(1)

The Tianshan region encompasses many countries and regions, and obtaining comprehensive streamflow observation data is challenging;

-

(2)

Due to scarcity of observation data and complex terrain and climate conditions, the simulation accuracy of hydrological models in this region is limited;

-

(3)

Although some studies have used improved hydrological models and machine learning methods to simulate streamflow, they are limited to individual watersheds, and multi-watershed streamflow simulation on daily scale is especially lacking.

Therefore, this study integrated data from domestic and international stations to reconstruct streamflow observations in the Tianshan Mountains using improved HBV and LSTM models. We produced the TSWS dataset, which includes daily streamflow data from 56 watersheds and monthly streamflow data from 89 watersheds in Tianshan Mountains in 1901–2019. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive and long-term streamflow modelling and data reconstruction at the watershed scale in Tianshan Mountains. The results of this study compensate for the lack of comprehensive coverage of small-basin streamflow data in Tianshan, and provide a systematic data support for water resource management and climate change impact assessment in the region.

Methods

The technology roadmap of this study, including relevant data, methodology, and the main structural framework, is shown in Fig. 1. Considering the advantages of the HBV hydrological model in physical interpretability and long-term hydrological simulation, and the wide application of LSTM model in capturing nonlinear relationships and hydroclimatic simulation, we use these two models to reconstruct and compare streamflow in the Tianshan region, respectively. First, we evaluated and preprocessed the input data required by the two models, and then used the two models to reconstruct the daily and monthly streamflow in the Tianshan region, compared the simulation results of the two models during the training and testing periods, and finally generated a dataset to describe the current status of streamflow.

Hydrological observation data

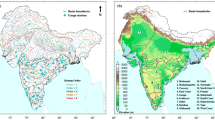

Hydrological monitoring was established in the former Soviet Union at the beginning of the 20th century and became common in the 1980s31. In this study, hydrological observation data of Tianshan Mountains in China were collected from inland rivers and lakes in the Annual Hydrological Report of the People’s Republic of China (HRC)32 and hydrological observation data outside the country were selected from the GRDC dataset33. HRC stations in which the hydrological stations are located in the CAWT region are shown in Table S1, and the Global Runoff Data Centre (GRDC; https://grdc.bafg.de/) stations are listed in Table S2. A total of 56 daily-scale streamflow observations were obtained for the CAWT region. In addition, 89 monthly-scale streamflow station data were obtained, including 56 daily-scale station data composited to the monthly scale (Fig. 2). The shortest of these time series is eight years, which meets the time requirements for the training period in the hydrological model; the longest is 66 years, with 80% of the stations being over 15 years old. We divided available data into training, validation, and testing periods for the subsequent simulation. Specific period divisions for each station are listed in Tables S3 and S4.

Map of the study area including hydrological stations, river systems, boundaries of large and small watersheds, elevations, and locations. HRC stations are hydrological observation stations recorded in the Annual Hydrological Report of the People’s Republic of China, and GRDC stations are derived from the Global Runoff Data Centre. (The standard map number is GS (2021) 5443, the base map is not modified, the following is the same).

We divided the study area into nine river systems: Kashgar River, Aksu River, Weigan & Dina River, Kaidu & Kongque River, Rivers in the northern Tianshan Mountains, Ebinur Lake, Ili River, Syr Darya, and Amu Darya (Fig. 2). The nine river systems were then divided into 89 watersheds (i.e., watersheds delineated by hydrological stations), 43 hydrological stations from the GRDC that directly used the GRDC’s officially published level 4 and 5 watershed ranges, and 46 hydrological stations from the Annual Hydrological Report of the People’s Republic of China that referenced the GRDC results and relied on the ArcGIS analysis tool to extract basin extents. Detailed river system and watershed information can be found in Tables S1 and S2.

Meteorological datasets

Regarding the selection of meteorological datasets, we mainly considered the long time series, multivariate, and scientific nature of the data. Variables such as precipitation, mean temperature, maximum temperature, minimum temperature, wind speed, barometric pressure, solar radiation, relative humidity, and potential evapotranspiration, were required to perform the simulation reconstruction of streamflow data. We calculated the potential vapor dispersion mainly based on the Penman formula recommended by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Details about the methodology are provided in Allen et al.34. We selected the third-round climate simulation datasets35 introduced by the Inter-Sectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project (ISIMIP; https://www.isimip.org/). The project contains multiple datasets and can cater to the long-term and multivariate nature of the study36. To ensure the scientific and rigorous nature of the study, we compared data from the historical period of the three datasets, that is, 20CRv3-ERA5, 20CRv3-W5E5, and GSWP3-W5E535, with daily Global Historical Climatology Network (GHCN; https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/data/) data. The evaluation indices used for meteorological datasets were the mean absolute error (MAE), NSE, relative bias (PBIAS), determination coefficient (R2), root-mean-square error (RMSE), ratio of the RMSE to the standard deviation of measured data (RSR), and comprehensive rating index (CRI), as described by Li et al.37 and in Methods “Streamflow simulation assessment criteria”. The results of the evaluation are presented in Tables S5 and S6, Figures S1–S3, and Text S1. Based on the results of the final assessment, we selected the 20CRv3-W5E5 dataset as an alternative to meteorological data as the input data for the next streamflow simulation.

HBV hydrological model

The HBV model17 is a semi-distributed hydrological model with a good hydrological simulation26,38,39,40,41. The HBV hydrological model consists of snowmelt, soil, response, and catchment modules in the main body38. Different modules, such as a glacier module, can be added depending on the status of the study area. In this study, the command-line version of the HBV-light model published by Seibert42,43 at the University of Zürich, Switzerland, was selected to simulate the major watersheds of Tianshan Mountains.

Preprocessing of input data

First, we divided the watersheds into different combinations based on the Digital Elevation Model (DEM) delineation of each subbasin using elevation bands, land use types, and slope orientation data. Figure S4a shows that the region was divided into 14 elevation bands and most of the area ranged between 1000–4000 m. The highest altitude is >6000 m, accounting for 0.02% of the total area of the Tianshan Mountains, mainly located in the Middle Tianshan Mountains. Land-use types were divided into three categories, with ~71.5% of the area covered by vegetation and only 2.52% of the area covered by glaciers (mainly at high altitudes). Glaciers cover a small area but represent large freshwater reserves (Figure S4b). In addition, three main slope directions were identified, that is, north, south, and east–west, with a balanced share of 30.58%, 31.22%, and 38.20%, respectively (Figure S4c). Combining the results of the three data classifications, for example, the percentage of area with a north-slope orientation in the vegetation cover within the 500–1000 m elevation band.

Other input data, such as precipitation, temperature (Tmax, Tmin), and potential evapotranspiration (PET), were interpolated to the center of mass of each elevation band. Raster data within the basin were then area-weighted to obtain average precipitation, temperature, and PET data at the spatial scale of the basin, a practice that corresponds well with the streamflow data.

Model setup

In this study, the snowy and glacial landscapes of the Tianshan Mountains were considered, and a glacier module was added to the standard modules (snowmelt, soil, response, and catchment modules) to simulate the streamflow from each basin on both daily and monthly scales. The model contains 26 main parameters that must be tuned. Table 1 lists the parameter names and information such as the range of values. Simultaneously, we used the Monte Carlo sampling method to rate 26 HBV parameters, set the maximum number of simulations to 3000, and set NSE > 0.3 to judge if the rate passed the test. Table 1 lists the parameters and rate ranges.

LSTM model

Neural networks are powerful black-box models that can be used to determine the numerical relationship between dependent and independent variables; however, they cannot reveal the physical mechanism between the two. The LSTM is a well-established neural network model that captures complex patterns and dependencies in time-series data44. It consists of four main parts45: (1) the input gate determines the importance of the input information, (2) the forgetting gate discards irrelevant information, (3) the state of the memory cell is updated, and (4) the output gate controls the current information of the memory cell and outputs the simulation results of the streamflow. Its main advantage is that it can overcome the problems of gradient vanishing and explosion in long time-series data46. Its superiority in streamflow simulation has been verified in many studies47. The LSTM was introduced in this study to simulate the runoff from all measured watersheds in Tianshan Mountains. Specific descriptions are provided by Li et al.44 and Xiang et al.48.

Input data

The LSTM model only requires meteorological data as independent variables. Therefore, based on the HBV model, meteorological data such as precipitation, maximum temperature, minimum temperature, average temperature, relative humidity, barometric pressure, solar radiation, wind speed and potential evapotranspiration, were interpolated to the altitudinal band of each watershed according to the delineated extent of each sub-basin, and then summed based on area weighting to obtain the average meteorological panel dataset of each basin to be used as the input data for the LSTM model.

In addition, considering the lagged response of the streamflow to meteorology, we included the meteorological “step length” parameter in the LSTM model. The range of the parameter step length is 0–7, that is, a value of 0 indicates that only the meteorological data of the day were introduced to the LSTM for the simulation and a value of 7 implies that meteorological data of the day and the previous seven days were used for the simulation.

Model setup

The LSTM can be a good black-box simulation of streamflow, but the parameter settings (e.g., the selection, number and order of network layers; choice of training method; and learning rate and loss rate in the training process) are very important because they affect the simulation results. Choosing a training method and tuning these parameters is more difficult and takes considerable amount of time. Bayesian optimization is a well-suited algorithm for optimizing the parameters of LSTM neural network models. It functions similarly to the Monte Carlo sampling method for the HBV hydrological model, both of which search for optimal parameters. The difference is that the Bayesian optimization, which considers the results of previous parameter choices, allows the next parameter optimization to approximate optimal parameters with greater probability.

Therefore, Bayesian optimization was applied in this study to LSTM neural network models to determine the optimal parameters and training methods for the LSTM. The optimization passes a threshold of NSE > 0.3 and uses a parallel approach to speed up the computation. The parameter descriptions and rate ranges are listed in Table 2.

Recorrection of simulation results

Re-correction of the streamflow data simulated by the LSTM improves the accuracy of the streamflow volume simulation. Commonly used correction methods include linear and nonlinear correction, quantile correction based on specific distributions and empirical distribution quantile correction. The correction methods adapted to Tianshan Mountains include linear scaling (LS)49, local intensity scaling (LOCI)50, power transformation (PT)51, gamma distribution mapping (DM), and quantile mapping (QM)52,53. Based on existing studies, gamma DM was selected in this study for the first correction of the simulated streamflow volume. The corrected runoff volume was then used as the volume to be corrected for LS. The first correction focuses on the statistical distribution of the data and the second correction removes the bias in the modelled data that exists in the multi-year monthly means. Please refer to Fang et al.53 study for specifications regarding both methods.

Streamflow simulation assessment criteria

In this study, statistical criteria (i.e., S-test) proposed by Moriasi et al.54 were used to assess the performance of the streamflow data simulated by the two models in the Tianshan Mountains: NSE ≥ 0.5, PBIAS ≤ 25%, and RSR ≤ 0.7. If the modelling results meet or exceed the criterion, the modelled data have a high level of confidence and can be used for streamflow-related studies. This standard is now widely used in assessment studies of hydrometeorological data modelling54,55. The NSE56 reflects the overall fitting effect of the streamflow data57. The closer the value of NSE is to 1, the better is the simulation effect. Values between 0 and 1 are considered as acceptable. Simulation results between -∞ and 0 are often not recognized. PBIAS58 presents deviations from the modelled data as a percentage result and clearly indicates areas in which modelling is less effective59. RSR was proposed by Singh et al.60 standardized the RMSE by the standard deviation of the observed data and clarified the definition of “low.” The lower the RMSE is, the better is the simulation effect54. A lower RSR represents a smaller RMSE, indicating better simulation of the data. The relevant equations are as follows:

where \({X}_{{mi}}\) denotes the ith simulated value, \({X}_{{oi}}\) is the ith observation, \(\bar{X}\) is the mean of the observations, and n is the total number of observations.

Data Records

TSWS dataset can be found on the National Tibetan Plateau Data Center61. It has 2 folders and a table file named “basins.xlsx”.

File 1: basins.xlsx. This file describes basic information on basins, e.g. basins’ name, source, outlet position, area, and so on. It also contains the S-test results of every daily and monthly simulation. The “TRUE” means passing the S-test and the empty means the opposite.

Folder 1: daily. The daily folder contains the code of daily LSTM model and a folder named ‘Data upload’ in Chinese. It has 56 table files (*.csv) and each one contains a basin’s daily streamflow simulation data. The 1st column is date and the 2nd column is the simulated streamflow (m³/s).

Folder 2: monthly. The monthly folder is the same as the daily folder but contains the code of monthly LSTM model and the monthly streamflow simulation data (89 table files [*.csv]).

Technical Validation

Simulation and recorrection of LSTM models during the training period

Evaluation of daily-scale simulation and recorrection results of LSTM model

We evaluated the results of streamflow simulations at the daily scale of the LSTM model for 56 watersheds in Tianshan Mountains using data measured during the training period. The spatial distribution of NSE, RSR, PBIAS, and S-test for the LSTM daily-scale simulation in the training period are shown in Fig. 3. The results show that, overall, the LSTM performs better in streamflow simulation compared with the HBV hydrological model. Among the 56 watersheds, 37 simultaneously met all three assessment criteria. From an NSE perpective, a total of 38 river basins have NSE above 0.5. The highest NSE was observed for the MOUTH OF KASHKASU basin in the Chu River system (NSE = 0.87), followed by eight other watersheds; that is, AHeYaZi, PoChengZi, LaMaMiao, BaJiaHu, ShiMenZi, QingShuiHeZi, MeiYao, and TALGAR, with NSE > 0.8. These watersheds are mainly located in the central sub-basin of Tianshan, and rivers in the northern Tianshan Mountains. In total, 37 watersheds passed the RSR evaluation test and were included in the watersheds that passed the NSE test. Note that the PBIAS of 53 and 43 watersheds remained within ranges of -0.25 to 0.25 and -0.1 to 0.1, respectively. Figure 3d shows that the total number of watersheds that simultaneously satisfied all three evaluation criteria (i.e., passed the S-test) was 37, with a range of basin sizes. Overall, the simulation of the LSTM was better, and 66.07% of the streamflow data of the watersheds could be reconstructed better. Please refer to Table S7 and Text S2 for the optimal parameter setting and description of the LSTM model. The simulation results of daily-scale data of HBV hydrological model during the training period are shown in Figure S5, the optimal parameter settings are shown in Table S8, and detailed descriptions are shown in Text S4.

To improve the simulation accuracy of the LSTM and resolve the problem of underestimation in the LSTM simulation in the high-value area of streamflow, we first performed gamma DM correction on the LSTM simulation results and then used the corrected streamflow volume as the to-be-corrected volume for LS correction. The results indicate that the recorrection method improves the simulation results of the LSTM (Fig. 4). The evaluation indices of all watersheds increased, particularly the NSE and PBIAS. In addition, the number of watersheds that satisfied all three evaluation criteria (i.e., the S-test) simultaneously increased by five: QiQiaEr in the Aksu River system, BaYinBuLuKe in the Kaidu & Kongque River, SARYTOGAI and QiaFu in the Ili River, and CHINOR in the Amu Darya River. Consequently, 42 (75%) watersheds in Tianshan yielded better LSTM simulation results on a daily scale.

Evaluation of monthly-scale simulation and recorrection results of LSTM model

The spatial distributions of the NSE, RSR, PBIAS and S-tests for the training period of the LSTM model simulating monthly streamflow in 89 watersheds are shown in Fig. 5. In total, 63 watersheds had a NSE above 0.5, and 12 watersheds had a NSE above 0.9 (DUPULI, AHeYaZi, MeiYao, DAVSEAR, TAVILDARA, MOUTH OF KASHKASU, BaJiaHu, QingShuiHeZi, ShiMenZi, TALGAR, YingXiongQiao, and TASH-KURGAN). In 54 watersheds, the RSR was determined to be 0.7 or less, that is, 54 watersheds passed the RSR test, and were included in the 63 watersheds that passed the NSE test. In terms of PBIAS, a total of 86 watersheds remain within -0.15 to 0.15. Only the UCH-TEREK, SUDGINA, and AE watersheds failed to meet the criteria of the S-test. In summary, 77 watersheds simultaneously satisfied all three evaluation indices, that is, passed the S-test. The simulation provides an almost complete and perfect reproduction of the streamflow in Tianshan Mountains. The optimal parameter list of the LSTM model that additionally passed the S-test is shown in Table S9, with an initial learning rate between 0 and 1, L2 regularization factor between 0 and 0.01, gradient threshold between 0 and 3, and loss rate between 0 and 0.5. The best solution for 55% of the watersheds was the rmsprop solution. A 1-layer LSTM network can satisfy the best simulation for 65% of the watersheds. The evaluation results and descriptions of HBV simulated monthly-scale streamflow data are shown in Text S5 and Figure S6. The optimal parameters of monthly-scale simulated streamflow of HBV model are set in Table S10.

In addition we used the same correction method and process for the daily scale to further improve the accuracy of monthly-scale LSTM simulation results. The evaluation results are shown in Fig. 6. The recorrection method improves the simulation results of the LSTM, and the NSE, RSR, and PBIAS of each sub-basin increased. Specifically, the simulations were corrected for the most significant improvement in PBIAS, which was close to 0 in almost all watersheds. The worst PBIAS value was 1.44 × 10−16; therefore, the difference was negligible. The NSE also improved significantly, with 82 watersheds meeting the criteria (in contrast to 79). The RSR and NSE also increased. Based on the correction, 82 watersheds met the test criteria. The number of watersheds that simultaneously fulfill all three evaluation criteria (i.e., the S-test) increased by 5 (QiaQiGa in the Kashgar River system, BaiCheng in the Weigan & Dina River system, KeErGuTi in the Kaidu & Kongque River system, UST. Karakol in the Syr Dinar River system, and SUDGINA in the Amu Dinar River). In total, 82 watersheds passed the standards of the S-test after correction, with a pass rate of 92.13%.

Comparison of simulation results between HBV and LSTM during the testing period

Comparison of daily-scale simulation results between HBV and LSTM

After evaluating the simulation results of the training period, we further examined the simulation of the test period to more accurately determine how well the HBV and LSTM models simulated the streamflow from the small watersheds in Tianshan Mountains. First, we rate-set the daily-scale HBV and LSTM models applied to the testing period (see Table S4 for the testing period). The spatial distributions of the NSE, RSR, PBIAS, and S-tests of the two models for each basin test period are shown in Figure S7, Figure S8, and Fig. 7. Overall, the HBV was still poorly simulated during the test period, whereas the LSTM simulation results were similar to those of the training period and overall performed better. Focusing on the NSE, only 11 watersheds in the HBV met the test, whereas the LSTM had 37 and 40 watersheds with a NSE of 0.5 or higher before and after correction, respectively. In terms of the RSR, 11 watersheds passed the test criteria during the HBV test period, 37 watersheds met the test criteria before correction in the LSTM model, and the number of watersheds that met the criteria increased by four after correction. With respect to PBIAS, only eight watersheds met the test for HBV, whereas 48 watersheds passed the test for LSTM and 54 passed the test after correction. As a result, the numbers of watersheds that passed the S-test for the HBV and LSTM simulations were 7 and 40, respectively, and the LSTM simulation was much better than the HBV simulation. For the daily streamflow data simulation, we selected corrected LSTM simulation results. The results show that approximately 71.4% of the basin streamflow simulations performed better.

Comparison of monthly-scale simulation results between HBV and LSTM

The results of the monthly-scale simulations in the test period were examined similarly. The LSTM and HBV performed similarly in the training period, with the LSTM passing the S-test in far more watersheds than HBV (Figure S9, Figure S10, and Fig. 8). There were a total of 12 watersheds where the HBV simulation results met the NSE criteria (≥0.5), 75 LSTMs, and 76 corrected LSTMs; Passing the RSR test criteria, there were 12 watersheds for HBV, 75 for LSTM, and 76 for corrected LSTM. From the PBIAS test criteria, 8 watersheds passed for HBV, 76 watersheds passed for LSTM, and 81 watersheds passed for corrected LSTM. The final watersheds that passed the S-test had only 5 HBVs and 69 LSTMs, with a corrected LSTM of 70 and a pass rate of 78.7%. Therefore, we chose the simulation results of the corrected LSTM for the monthly-scale streamflow simulation of 89 watersheds, which had a streamflow pass rate of 78.7%, that is, 78.7% of the watersheds had a better streamflow simulation and could be used as the basic data for hydrological studies.

The streamflow simulations of the LSTM model for 40 watersheds (daily scale) and 70 watersheds (monthly scale) passed the S-test, that is, NSE ≥ 0.5, PBIAS ≤ 25%, and RSR ≤ 0.7. The pass rate of streamflow simulation was 71.4% (daily scale) and 78.7% (monthly scale), respectively. The LSTM reproduces the streamflow changes in the Tianshan region well.

Comparison of LSTM simulated data and observed data during the testing period

Comparison of daily-scale simulation results

We further performed time-series (testing period) comparisons of pre- and post-corrected LSTM daily-scale simulated data with the observed data for all watersheds, as shown in Figures S11-S14 and Fig. 9. We observed that the simulation effect before correction in the streamflow low-value area was already extremely close to the observed value, and the effect after correction is not significant. However, the simulated values of LSTM for extreme streamflow are low (Figures S11 and S12). Most of the corrected simulations showed significant improvements in extreme streamflow (Figures S13, S14 and Fig. 9). However, it remained difficult to capture some of the watersheds, especially in the second year of the test period. For example, in the ZhiCaiChang and NianPanZhuang watersheds in Figure S13, corrected streamflow simulation data were already very similar to the observed data in the first high-value area. However, in the second high-value area, the corrected simulation data were lower than the extreme values of the observed data. The sequence of observed data shows that the extreme values in the second year are significantly higher and in larger increments than those in the first year, which may lead to problems in the simulation process of the model, resulting in extreme values being more difficult to simulate. Overall, the LSTM and bias correction methods better simulate streamflow data. However, some gaps remain in the reproduction of extreme streamflow.

Sequence plots of the correction streamflow of daily LSTM simulation results and observed streamflow. The red line represents corrected LSTM simulation data, and the black line refers to observed data. An S-test of “1” and “0” means that the simulated data for the basin passes and fails, respectively.

Comparison of monthly-scale simulation results

Compared with the daily scale, the LSTM is more effective in simulating low and extreme values during streamflow simulations at a monthly scale. Figures S15-S17 show the simulation results of the LSTM before correction compared with the observed data. Figure 10, Figure S18, and Figure S19 show the data after correction in comparison with observed data. Underestimation of extremes remains present in precorrected simulation data including watersheds with an S-test of 1 such as QiaLaBeiLi and YaShi (Figure S19). Contrastingly, although corrected modelled data were also underestimated, they are relatively small and in many watersheds the simulated data are extremely close to the observed data. For example, most of the watersheds in Fig. 10 have simulated values that are extremely close to the low and high observed values. In summary, the monthly streamflow simulation was better than the daily streamflow simulation and the application of correction methods improves the capturing of extreme values.

Sequence plots of the correction streamflow of monthly LSTM simulation results and observed streamflow. Otherwise same as Fig. 11.

Uncertainty analysis

Considering most stations with daily records are limited to pre-2011, and no stations have monthly records after 1995, the biases and uncertainties must be considered. The Generalized likelihood uncertainty estimation (GLUE) method is introduced in this study. Excluding the best simulation result, the other results passing the S-test were collected to select 10 randomly. The 5th and 95th percentiles of those 10 results were calculated to show the uncertainties of the dataset. Therefore, we obtained the 5th and 95th percentile uncertainty range of the dataset and we have publicly released the uncertainty range along with the dataset. Figures S20 and S21 show the uncertainty range of all watersheds in the nine river systems at the daily-scale streamflow data during the testing period; and Figures S22–24 show the uncertainty range of the streamflow data at the monthly-scale. Regardless of the daily or monthly scale, the uncertainty range closely aligns with the simulation results. Additionally, we calculated the average uncertainty range at the daily and monthly scales for each watershed from 1901 to 2019. We found that for most sub-watersheds at the daily scale, the PBIAS between the uncertainty range (5th and 95th percentiles) and the best simulation results are within 0.2, while the PBIAS for all watersheds remains within 0.35 (Table S11). The results at the monthly scale are similar to those at the daily scale, with an even smaller PBIAS (Table S12). This indicates that even under simulations with different parameter sets, the simulated values vary within a small range, demonstrating the stability and accuracy of our results. Users can assess the dataset’s accuracy based on their research needs and determine whether to use it.

Characterization of spatial and temporal variability of streamflow

Annual streamflow time series analysis

We calculated and analysed the annual streamflow in the Tianshan region based on the monthly streamflow simulation data from LSTM. We divided the years 1901-2019 into four periods, including T1 (1901–1930), T2 (1931–1960), T3 (1961–1990), and T4 (1991–2019). According to the time series of annual streamflow in the Tianshan region (Fig. 11, Figures S25 and S26), the annual streamflow in most of the watersheds, compared with the T1 period, shows a trend of first rising (T2), then falling (T3), then rising (T4), and the most significant increase in T4 (by t-tests); and the other part of the watershed showed continuous downward or upward trends in T2 and T3, although it showed an upward trend in T4. See Figures S20 and S21 for more information on streamflow changes in the watersheds. In addition, we supplemented the characteristic values of the daily and monthly scale streamflow simulation data of each watershed from 1901 to 2019, including the mean, maximum, and minimum values. For specific characteristics, please refer to Tables S13 and S14.

In addition, the streamflow in most of the watersheds in the Tianshan region mutated in 1990–2000 (Figures S27–S29), and the means of these watersheds’ streamflow in 2000–2019 passed the t-test, i.e., the mean of the streamflow after the mutation differed significantly from the mean of the streamflow in 1901–1990 before the mutation. This result also verifies the streamflow trend in the Tianshan region in the time series.

Spatial distribution of mean annual streamflow and trends

From Fig. 12a, the runoff depth in the Tianshan region shows an overall spatial distribution that is higher on the western and southern regions and lower in the eastern and northern regions. This is mainly due to the water vapour from southeastern Asia and Siberia being lost on the way, so that less of it reaches the areas on the eastern and northern sides of the Tianshan. The western and southern areas of the Tianshan are directly exposed to water vapour from the western area of the Eurasian continent, with the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea being its main sources of evaporation. Although this water vapour is lost during transport, it still reaches more to the west and south relative to the east and north of the Tianshan, so that this is the main reason for the larger runoff depth in the western and southern regions of the Tianshan.

From Fig. 12b, the annual runoff depth of the watersheds in the Tianshan region as a whole shows an increasing trend and passes the significant test, and only some watersheds have a small change in the trend or a decreasing trend. The Amu Darya system has the largest mean trend in runoff depth of 0.22 mm/a, with trends ranging from -0.01 to 0.57 mm/a; the trend in multi-year runoff depth in the DAGANA-ATA watershed is -0.01 mm/a (p ≤ 0.01), and the trend in multi-year runoff depth in the ZARCHOB watershed is 0.05 mm/a (p ≤ 0.01).

Based on seasonal scales (Fig. 12c-j), runoff depth in Tianshan region is highest in summer, followed by in spring, and lowest in autumn and winter. The spatial distribution of the four seasons was consistent with the distribution of the annual mean; however, in autumn and winter runoff depth differed less in spatial distribution. Summer runoff depth was less variable and the trends did not pass the significance test in most watersheds. Winter runoff depth did not show significant trends throughout the Tianshan Mountains.

Usage Notes

This study reconstructed daily (monthly) streamflow observations from 56 (89) watersheds in the Tianshan Mountains based on the LSTM model. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive and long-term streamflow modelling and data reconstruction at the watershed scale in Tianshan Mountains. The results of this study compensate for the lack of comprehensive coverage of small-basin streamflow data in Tianshan. Therefore, we strongly recommend using this dataset for research on streamflow variations and component contributions across different temporal and watershed scales in the Tianshan region. At the same time, we acknowledge certain uncertainties in the dataset.

Firstly, although the streamflow simulation data for most watersheds have passed the S-test, users should consider potential uncertainties in any dataset62. Therefore, we have additionally provided 10 sets of simulated results, offering an uncertainty range as a reference for users. Additionally, it is critical to recognize the limitations of LSTM model63. Although it has great advantages in addressing complex time series problems23,48, we must acknowledge that they primarily rely on historical data for training, making it challenging to accurately simulate and extrapolate streamflow extremes64, especially at the daily scale. Finally, beyond the limitations of the model itself, there are uncertainties related to the data, such as observational errors, input data errors, data export errors, and errors in the data management process9. In future, we will continue to collect more streamflow observation data and integrate hydrological models, optimization algorithms, and machine learning approaches to improve the accuracy of streamflow simulations65.

Code availability

Codes for data and result analysis are freely available at https://cstr.cn/18406.11.Terre.tpdc.301422.

References

Ghiggi, G., Humphrey, V., Seneviratne, S. I. & Gudmundsson, L. G-RUN ENSEMBLE: A Multi-Forcing Observation-Based Global Runoff Reanalysis. Water Resour. Res. 57, e2020WR028787, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020WR028787 (2021).

Lian, H. et al. CN-China: Revised runoff curve number by using rainfall-runoff events data in China. Water Res. 177, 115767, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2020.115767 (2020).

Lorenz, C., Tourian, M. J., Devaraju, B., Sneeuw, N. & Kunstmann, H. Basin-scale runoff prediction: An Ensemble Kalman Filter framework based on global hydrometeorological data sets. Water Resour. Res. 51, 8450–8475, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014WR016794 (2015).

Bettadpur, S. UTCSR level-2 processing standards document for level-2 product release 0005. GRACE Rep. 327, 742 (2012).

Fekete, B. M., Looser, U., Pietroniro, A. & Robarts, R. D. Rationale for Monitoring Discharge on the Ground. J. Hydrometeorol. 13, 1977–1986, https://doi.org/10.1175/JHM-D-11-0126.1 (2012).

Ghiggi, G., Humphrey, V., Seneviratne, S. I. & Gudmundsson, L. GRUN: an observation-based global gridded runoff dataset from 1902 to 2014. Earth Syst. Sci. Data. 11, 1655–1674, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-11-1655-2019 (2019).

Laudon, H. et al. Save northern high-latitude catchments. Nat. Geosci. 10, 324–325, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2947 (2017).

Milzow, C., Krogh, P. E. & Bauer-Gottwein, P. Combining satellite radar altimetry, SAR surface soil moisture and GRACE total storage changes for hydrological model calibration in a large poorly gauged catchment. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 15, 1729–1743, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-15-1729-2011 (2011).

McMillan, H. K., Westerberg, I. K. & Krueger, T. Hydrological data uncertainty and its implications. Wires Water 5, e1319, https://doi.org/10.1002/wat2.1319 (2018).

Gudmundsson, L. & Seneviratne, S. I. Observation-based gridded runoff estimates for Europe (E-RUN version 1.1). Earth Syst. Sci. Data. 8, 279–295, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-8-279-2016 (2016).

Zaherpour, J. et al. Worldwide evaluation of mean and extreme runoff from six global-scale hydrological models that account for human impacts. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 65015, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aac547 (2018).

Birkinshaw, S. J., James, P. & Ewen, J. Graphical user interface for rapid set-up of SHETRAN physically-based river catchment model. Environ. Modell. Softw. 25, 609–610, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2009.11.011 (2010).

Müller Schmied, H. et al. Variations of global and continental water balance components as impacted by climate forcing uncertainty and human water use. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 20, 2877–2898, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-20-2877-2016 (2016).

Arnold, J. G., Srinivasan, R., Muttiah, R. S. & Williams, J. R. Large area hydrologic modeling and assessment part I: model development 1. JAWRA J. American Water Resour. Assoc. 34, 73–89 (1998).

Srinivasan, R., Ramanarayanan, T. S., Arnold, J. G. & Bednarz, S. T. Large area hydrologic modeling and assessment part II: model application. J. American Water Resour. Assoc. 34, 91–101, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-1688.1998.tb05962.x (1998).

Beck, H. E. et al. Global-scale regionalization of hydrologic model parameters. Water Resour. Res. 52, 3599–3622, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015WR018247 (2016).

Bergström, S. The HBV model–its structure and applications: SMHI. https://www.smhi.se/en/publications/the-hbv-model-its-structure-and-applications-1.83591 (2015).

Arheimer, B. et al. Global catchment modelling using World-Wide HYPE (WWH), open data, and stepwise parameter estimation. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 24, 535–559, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-24-535-2020 (2020).

Fowler, K. et al. Simulating Runoff Under Changing Climatic Conditions: A Framework for Model Improvement. Water Resour. Res. 54, 9812–9832, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018WR023989 (2018).

Kumar, A., Singh, R., Jena, P. P., Chatterjee, C. & Mishra, A. Identification of the best multi-model combination for simulating river discharge. J. Hydrol. 525, 313–325, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2015.03.060 (2015).

Baccouche, M., Mamalet, F., Wolf, C., Garcia, C. & Baskurt, A. Sequential deep learning for human action recognition. In Human Behavior Understanding, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 7065, The Netherlands, Proceedings, Springer, 29-39. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-25446-8_4 (2011).

Van, S. P. et al. Deep learning convolutional neural network in rainfall–runoff modelling. J. Hydroinf. 22, 541–561, https://doi.org/10.2166/hydro.2020.095 (2020).

Kratzert, F., Klotz, D., Brenner, C., Schulz, K. & Herrnegger, M. Rainfall–runoff modelling using Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 22, 6005–6022, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-22-6005-2018 (2018).

Fan, H. et al. Comparison of Long Short Term Memory Networks and the Hydrological Model in Runoff Simulation. Water. 12, 175, https://doi.org/10.3390/w12010175 (2020).

Hu, C. et al. Deep learning with a long short-term memory networks approach for rainfall-runoff simulation. Water 10, 1543, https://doi.org/10.3390/w10111543 (2018).

Yang, Z. & Bai, P. Response of runoff and its components to climate change in the Manas River of the Tian Shan Mountains. Adv. Clim. Change Res. 15, 62–74, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accre.2024.01.005 (2024).

Jin, C., Wang, B., Cheng, T., Dai, L. & Wang, T. How much we know about precipitation climatology over Tianshan Mountains–the Central Asian water tower. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 21, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00572-x (2024).

Chen, Y., Li, W., Deng, H., Fang, G. & Li, Z. Changes in Central Asia’s water tower: past, present and future. Sci. Rep. 6, 35458, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep35458 (2016).

Liang, W., Chen, Y., Fang, G. & Kaldybayev, A. Machine learning method is an alternative for the hydrological model in an alpine catchment in the Tianshan region, Central Asia. J. Hydrol.: Reg. Stud. 49, 101492, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrh.2023.101492 (2023).

Chen, F. et al. Ecological and societal effects of Central Asian streamflow variation over the past eight centuries. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 5, 27, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-022-00239-5 (2022).

Shahgedanova, M. et al. Changes in the mountain river discharge in the northern Tien Shan since the mid-20th Century: Results from the analysis of a homogeneous daily streamflow data set from seven catchments. J. Hydrol. 564, 1133–1152, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2018.08.001 (2018).

Hydrology Bureau of the Ministry of Water Resources of the People’s Republic of China. Hydrological Yearbook of the People’s Republic of China: Hydrological Data of Inland Rivers and Lakes. Hydrology Bureau of the Ministry of Water Resources, Beijing (1978–2011).

Global Runoff Data Centre (GRDC). Global River Discharge Dataset. Federal Institute of Hydrology (BfG), Koblenz, Germany. https://www.bafg.de/GRDC (2023).

Allen, R. G., Pereira, L. S., Raes, D. & Smith, M. Crop evapotranspiration-Guidelines for computing crop water requirements-FAO Irrigation and drainage paper 56. Fao, Rome. 300, D5109 (1998).

Lange, S., Mengel, M., Treu, S. & Büchner, M. ISIMIP3a atmospheric climate input data (v1.2). ISIMIP Repository. https://doi.org/10.48364/ISIMIP.982724.2 (2023).

Wei, W. et al. Spatiotemporal variability in extreme precipitation and associated large-scale climate mechanisms in Central Asia from 1950 to 2019. J. Hydrol. 620, 129417, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2023.129417 (2023).

Li, S., Chen, Y., Wei, W., Fang, G. & Duan, W. The increase in extreme precipitation and its proportion over global land. J. Hydrol. 628, 130456, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2023.130456 (2024).

Nonki, R. M., Lenouo, A., Tshimanga, R. M., Donfack, F. C. & Tchawoua, C. Performance assessment and uncertainty prediction of a daily time-step HBV-Light rainfall-runoff model for the Upper Benue River Basin, Northern Cameroon. J. Hydrol.: Reg. Stud. 36, 100849, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrh.2021.100849 (2021).

Radchenko, I., Dernedde, Y., Mannig, B., Frede, H. & Breuer, L. Climate change impacts on runoff in the Ferghana Valley (Central Asia). Water Resour. 44, 707–730, https://doi.org/10.1134/S0097807817050098 (2017).

Seibert, J. & Bergström, S. A retrospective on hydrological catchment modelling based on half a century with the HBV model. Hydrol. Earth. Syst. Sci. 26, 1371–1388, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-26-1371-2022 (2022).

Seibert, J. & Vis, M. J. P. Teaching hydrological modeling with a user-friendly catchment-runoff-model software package. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 16, 3315–3325, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-16-3315-2012 (2012).

Seibert, J. Estimation of Parameter Uncertainty in the HBV Model. Hydrol. Res. 28, 247–262, https://doi.org/10.2166/nh.1998.15 (1997).

Seibert, J. HBV light version 2, user’s manual. Department of Earth Sciences, Uppsala University, Uppsala (2005).

Li, W., Kiaghadi, A. & Dawson, C. High temporal resolution rainfall–runoff modeling using long-short-term-memory (LSTM) networks. Neural Comput. Appl. 33, 1261–1278, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-020-05010-6 (2021).

Liu, Y., Zhang, T., Kang, A., Li, J. & Lei, X. Research on Runoff Simulations Using Deep-Learning Methods. Sustain. 13, 1336, https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031336 (2021).

Han, H., Choi, C., Jung, J. & Kim, H. S. Deep Learning with Long Short Term Memory Based Sequence-to-Sequence Model for Rainfall-Runoff Simulation. Water 13, 437, https://doi.org/10.3390/w13040437 (2021).

Peng, A., Zhang, X., Xu, W. & Tian, Y. Effects of Training Data on the Learning Performance of LSTM Network for Runoff Simulation. Water Resour. Manag. 36, 2381–2394, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-022-03148-7 (2022).

Xiang, Z., Yan, J. & Demir, I. A Rainfall-Runoff Model With LSTM-Based Sequence-to-Sequence Learning. Water Resour. Res. 56, e2019WR025326, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019WR025326 (2020).

Lenderink, G., Buishand, A. & van Deursen, W. Estimates of future discharges of the river Rhine using two scenario methodologies: direct versus delta approach. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 11, 1145–1159, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-11-1145-2007 (2007).

Schmidli, J., Frei, C. & Vidale, P. L. Downscaling from GCM precipitation: a benchmark for dynamical and statistical downscaling methods. Int. J. Climatol. 26, 679–689, https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.1287 (2006).

Teutschbein, C. & Seibert, J. Bias correction of regional climate model simulations for hydrological climate-change impact studies: Review and evaluation of different methods. J. Hydrol. 456-457, 12–29, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2012.05.052 (2012).

Themessl, M. J., Gobiet, A. & Heinrich, G. Empirical-statistical downscaling and error correction of regional climate models and its impact on the climate change signal. Clim. Change. 112, 449–468, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-011-0224-4 (2012).

Fang, G., Yang, J., Chen, Y. & Zammit, C. Comparing bias correction methods in downscaling meteorological variables for a hydrologic impact study in an arid area in China. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 19, 2547–2559, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-19-2547-2015 (2015).

Moriasi, D. N. et al. Model Evaluation Guidelines for Systematic Quantification of Accuracy in Watershed Simulations. Trans. Asabe. 50, 885–900, https://doi.org/10.13031/2013.23153 (2007).

Jia, Y. et al. Characteristics of glacier ice melt runoff in three sub-basins in Urumqi River basin, eastern Tien Shan. J. Hydrol.: Reg. Stud. 53, 101772, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrh.2024.101772 (2024).

Nash, J. E. & Sutcliffe, J. V. River flow forecasting through conceptual models part I—A discussion of principles. J. Hydrol. 10, 282–290, https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1694(70)90255-6 (1970).

Wen, L. et al. Factors influencing calibration of a semi-distributed mixed runoff hydrological model: A study on nine small mountain catchments in China. J. Hydrol.: Reg. Stud. 47, 101418, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrh.2023.101418 (2023).

Zhang, H., Huang, G., Wang, D. & Zhang, X. Multi-period calibration of a semi-distributed hydrological model based on hydroclimatic clustering. Adv. Water Resour. 34, 1292–1303, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advwatres.2011.06.005 (2011).

Gupta, H. V., Sorooshian, S. & Yapo, P. O. Status of automatic calibration for hydrologic models: Comparison with multilevel expert calibration. J. Hydrol. Eng. 4, 135–143, https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1084-0699(1999)4:2(135) (1999).

Singh, J., Knapp, H. V. & Demissie, M. Hydrologic modeling of the Iroquois River watershed using HSPF and SWAT. J. American Water Resour. Assoc. 41, 343–360, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-1688.2005.tb03740.x (2004).

Li, S., Wei, W., Chen, Y., Duan, W., Fang, G. The Tien Shan watersheds streamflow dataset (TSWS) (1901–2019). National Tibetan Plateau / Third Pole Environment Data Center, https://doi.org/10.11888/Terre.tpdc.301422 (2024).

Hu, X., Shi, S., Zhou, B. & Ni, J. A 1 km monthly dataset of historical and future climate changes over China. Sci. Data. 12, 436 (2025).

Dong, W. et al. A global urban tree leaf area index dataset for urban climate modeling. Sci. Data. 12, 426 (2025).

Deng, H., Chen, W. & Huang, G. Deep insight into daily runoff forecasting based on a CNN-LSTM model. Nat. Hazards. 113, 1675–1696 (2022).

Xu, Y. et al. Research on particle swarm optimization in LSTM neural networks for rainfall-runoff simulation. J. Hydrol. 608, 127553, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2022.127553 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (W2412135, 42130512) and the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB0720203). The authors would also like to acknowledge the Annual Hydrological Report of the People’s Republic of China, the Global Runoff Data Centre (GRDC; https://grdc.bafg.de/), and the Inters-Sectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project (ISIMIP; https://www.isimip.org/) for publicly available data. The authors also thank the National Tibetan Plateau Data Center (TPDC) for providing the data platform.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Shuai Li: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft. Wei Wei: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft. Yaning Chen: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Weili Duan: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Gonghuan Fang: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, S., Wei, W., Chen, Y. et al. TSWS: An observation-based streamflow dataset of Tianshan Mountains watersheds (1901–2019). Sci Data 12, 708 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05046-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05046-0