Abstract

Gypsophila vaccaria Sm., a member of the Caryophyllaceae family, is known for its dry mature seeds, which are widely used in traditional Chinese medicine as “Wang Bu Liu Xing”. This study presents a high-quality, chromosome-scale genome assembly of G. vaccaria, integrating Hi-C technology with PacBio and Illumina sequencing data. The final assembled genome measures 1.09 Gb in total length, with a contig N50 of 9.73 Mb and a scaffold N50 of 73.3 Mb, and complete benchmarking universal single-copy orthologs (BUSCO) for the genome and protein modes were 95.9% and 94.9%. Notably, 99.93% of the sequences are anchored to 15 pseudo-chromosomes. A total of 21,795 protein-coding genes were predicted, and repetitive elements were found to constitute 80.43% of the assembled genome. This chromosome-level genome assembly serves as an invaluable resource for future research, including functional genomics and molecular breeding of G. vaccaria.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

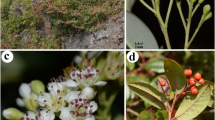

Gypsophila vaccaria Sm., an annual herbaceous plant in the Caryophyllaceae family1, is known in traditional Chinese medicine as “Wang Bu Liu Xing” for its dry mature seeds, which are used to treat amenorrhea, urinary tract infections and to stop bleeding2,3 (Fig. 1). The bioactive constituents of G. vaccaria seeds include triterpenoid saponins, cyclic peptides, flavonoids, and crude polysaccharides4,5,6. According to the 2010 edition of the Pharmacopoeia of China, vaccarin is the primary bioactive ingredient in the seeds and is used as the defining marker of Wang Bu Liu Xing2.

Most medical research on G. vaccaria has focused on the extraction, isolation, and characterization of its main medicinal ingredient, vaccarin, along with studies on its pharmacology, toxicology, and the development and quality evaluation of new drugs7,8. Based on the acquisition of genomes and genetic information of genes, a series of difficult problems faced in the research of traditional Chinese medicine can be solved through the research and development of gene functions9,10,11. However, the lack of high-quality genomic data for G. vaccaria has hindered research into the biosynthesis and accumulation of its essential medicinal components, as well as the identification of the relevant pathways and genes involved in these processes. This gap limits the production and broader application of this important traditional Chinese medicine. Therefore, investigating the genome of G. vaccaria is crucial for analyzing its genetic background and understanding the biological mechanisms behind its medicinal properties. This knowledge can subsequently inform the selection of superior varieties of Chinese herbal medicines and facilitate genetic enhancement.

A high-quality, chromosome-level genome of G. vaccaria (2n = 30) was obtained by generating approximately 26.79 Gb of PacBio HiFi data and 14.07 Gb of transcriptome data based on the Illumina platform. We also integrated the 120.6 Gb of high-throughput chromosome conformation capture (Hi-C) sequencing data. This well-annotated genome offers valuable insights into the biosynthesis of the medicinal components of G. vaccaria and lays the groundwork for future studies on genetic improvement.

Methods

Sample collection and genome sequencing

Fresh leaves of G. vaccaria were collected from a healthy plant cultivated at Hexi Corridor Medicinal Plant Plantation (Fig. 1a,b). The leaves were washed with distilled water, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C until sequencing. Genomic DNA was extracted to construct a library using the SMRTbell Express Template Prep Kit, following the manufacturer’s protocol. Genome sequencing was conducted on the PacBio Revio platform (BerryGenomics, Beijing, China), yielding 26.79 Gb of data with an average read length of 15.3 kb and an N50 of 15.1 kb (Table 1). Additionally, whole-genome sequencing was performed on the Illumina HiSeq2500 platform, generating 21.77 Gb of short reads for genome survey analysis (Table 1).

To accurately annotate the G. vaccaria genome, transcriptome sequencing was conducted on the fresh leaves using the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform. Low-quality reads were filtered out by using fastp12, a total of 14.07 Gb of clean data were obtained. Additionally, fresh leaves were used to construct a library for Hi-C sequencing13. The Hi-C library was prepared according to standard procedures and sequenced on the Illumina Novaseq 6000 platform, generating 120.6 Gb of raw data with approximately 110 × genome coverage (Table 1).

Genomic characteristics estimation

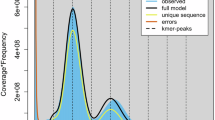

The genome size and heterozygosity of G. vaccaria were estimated using two complementary methods. First, root tips of G. vaccaria, along with those of reference species Solanum lycopersicum and Zea mays, were stained, and the nuclear suspensions were analyzed using a flow cytometer14. The genome size of G. vaccaria was calculated based on fluorescence intensity, resulting in estimates of 1.11 Gb and 1.16 Gb when using the two reference species (Table 2). The second estimation method involved k-mer analysis. The k-mer distribution of both short reads and HiFi reads was calculated using Jellyfish with the parameter “-k 19”15. GenomeScope (v2.0)16 was then used to analyze the k-mer distribution, providing estimates for genome size and heterozygosity rate. This analysis yielded estimated genome sizes of 962 Mb and 874 Mb, with heterozygosity rates of 0.0971% and 0.74%, respectively (Fig. 2).

Genome assembly and scaffolding

The PacBio HiFi reads were assembled using Hifiasm with default parameters17. The initial contigs were aligned to the HiFi reads using Minimap218 with the parameter “-xasm20”, and the results were used to calculate the sequencing depth of each contig. Simultaneously, the initial contigs were compared against organelle genomes using BLASTn with the parameters “-evalue 1e-5 -perc_identity 0.8 -task megablast”19. Contigs with high sequencing depth (>150×) and high organelle genome coverage (>85%) were removed. The remaining contigs were then aligned both to the HiFi reads and to themselves to eliminate haplotigs using Purge_Dups v1.2.6 with default parameters20. This analysis resulted in an assembly size of 1,089.9 Mb and an N50 length of 9.73 Mb (Table 3). Following the removal of redundancy, Hi-C paired-end reads were employed to construct pseudo-chromosomes using Haphic21. The chromosome-scale pseudomolecules were subsequently gap-filled and polished using TGS-GapCloser222 and NextPolish223. The final genome assembly was organized into 15 pseudo-chromosomes, resulting in a total genome size of 1.09 Gb and an N50 length of 73.3 Mb (Table 3, Fig. 3).

To evaluate the completeness of the genome assembly, different strategies were employed. Short reads and HiFi reads were mapped to the assembled genomes using BWA and Minimap2 to estimate mapping rates and genome coverage18,24. The results indicate that over 99% of the short reads and HiFi reads could be mapped back to the genome (Table 4). Merqury and LAI analyses were conducted to assess the quality of the genome assembly, revealing that each pseudo-chromosome has high QV values (Table 5) and an overall LAI value of 17.33 for the entire genome25,26. These assessment results suggest a high quality for the G. vaccaria genome. Moreover, Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (embryophyta_odb10) were used to calculate the completeness of the assembled genome and the subsequent annotations of protein-coding genes27. The completeness values for the genome and protein modes were 95.9% and 94.9%, respectively, demonstrating the high accuracy of the genome assembly and gene prediction (Fig. 4).

Annotation of repetitive elements

Transposable elements in the genome were annotated using a combination of ab initio prediction and homology searching. A consensus sequence library was built using LTR_FINDER28, RepeatScout29, and RepeatModeler30. Repeat regions were annotated using Repeatmasker31 based on the aforementioned library and the RiTE database32. Repeat sequences at the protein level were identified using RepeatProteinMask, while tandemly repeated sequences were identified using Tandem Repeats Finder (TRF)33. Overall, 80.43% of the whole genome was annotated as repetitive elements using both homology-based and de novo prediction methods. This included 54.5% retrotransposons (594.0 Mb) and 6.0% DNA transposons (65.4 Mb) (Fig. 5, Table 6).

Gene prediction and functional annotation

Protein-coding gene prediction was performed using a combined approach of homology-based, ab initio, and RNA-Seq-assisted predictions. First, two transcriptomes derived from G. vaccaria leaves were mapped to the genome using HISAT234, and the aligned RNA-Seq reads were processed with Samtools35 to generate BAM files. These BAM files were used in a genome-guided transcriptome assembly with StringTie236. The transcriptome assemblies provided RNA evidence for BRAKER37, which utilized both AUGUSTUS38 and GeneMark-ET39 to refine gene predictions by training models on RNA-Seq hints, improving gene structure accuracy. For homology-based evidence, a comprehensive protein database, including odb10_plants (3,510,742 proteins) as well as proteins from three Caryophyllaceae species—Saponaria officinalis (GCA_040167595.1)40, Silene conica (GCA_0292556 85.2)41, and Gypsophila paniculata (GCA_032274805.1)42-was used to enhance the annotation through protein sequence alignment and homology-informed model training in AUGUSTUS38. Ab initio prediction was carried out using trained models from RNA-Seq and protein evidence data, allowing BRAKER37 to perform gene structure inference with minimal manual intervention. Finally, the combined results from these strategies produced a comprehensive annotation, identifying a total of 21,795 protein-coding genes and 24,568 transcripts for G. vaccaria.

For functional annotation, protein-coding genes were compared with homologs in the SwissProt and NR databases using BLASTP (e-value = 10−5)43. Domains and gene ontology terms were annotated through sequence comparisons using HMMER44 with the Pfam45 and GO databases46. KEGG pathway annotations were derived from comparisons with homologs in the KEGG databases47. Over 97% of total predicted proteins were found to have homologs with functional annotations (Table 7).

For non-coding genes, rRNA genes were predicted using Barrnap v0.9 (https://github.com/tseemann/barrnap), identifying 15,477 rRNA features. Additionally, 1,287 candidate tRNA genes were predicted using tRNAscan-SE48. Other non-coding RNA genes were identified by searching against Rfam.cm database49, with clan information provided by Rfam.clanin to group related families using Cmscan, resulting in the identification of 5,724 candidate genes.

Data Records

Technical Validation

To ensure the quality and validity of our data, we implemented rigorous quality control measures during sequencing, assembly, and annotation.

Quality control for sequencing data

For Illumina DNA sequencing, raw reads were filtered to remove adaptors and low-quality sequences (quality score < 20), retaining 95.90% of the original reads as high-quality reads. This resulted in 21.67 Gb of clean data, corresponding to approximately 19.2 × genome coverage. Similarly, for Hi-C DNA sequencing, after quality filtering (quality score < 20), 97.34% of reads were retained, generating 116.18 Gb of clean data (~101.9× genome coverage). For HiFi sequencing, the N50 read length reached 15.12 Kb, with the longest read spanning 40.9 Kb and an average read length of 15.27 Kb. Additionally, for transcriptome sequencing, two datasets were obtained, with Q20 values of 97.48% (6.54 Gb) and 98.30% (6.84 Gb), respectively. These high-quality sequencing data ensure the accuracy and reliability of the subsequent genome assembly and analyses.

Genome assembly quality assessment

We assessed the genome assembly based on contiguity, completeness, and correctness. The assembled genome exhibited a scaffold N50 of 73.29 Mb, with 15 chromosomal-level scaffolds successfully obtained. Completeness was evaluated using BUSCO analysis with the ‘embryophyta_odb10’ database, revealing a high completeness score of 97.96%, with 95.79% of sequences classified as complete and 2.17% as fragmented. To verify the accuracy of the genome assembly, we mapped both Illumina and HiFi sequencing reads to the assembled genome, achieving mapping rates of 99.03% and 99.99%, respectively. Furthermore, transcriptome data were mapped to the genome, yielding mapping rates of 96.74% and 95.38%. These results, along with phylogenomic analysis, collectively demonstrate the high quality and accuracy of the assembled genome.

Code availability

All software and pipelines were implemented in full compliance with the manuals and protocols specified by the respective published bioinformatics tools. No custom programming or coding was employed.

References

Li, J. Flora of China. Harvard Papers in Botany 13, 301–302 (2007).

Pharmacopoeia, C. N. Pharmacopoeia of People’s Republic of China Part 1. (China Medical Science Press, Beijing, 2000).

Mao, X. et al. Crude polysaccharides from the seeds of Vaccaria segetalis prevent the urinary tract infection through the stimulation of kidney innate immunity. J Ethnopharmacol 260, 112578, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2020.112578 (2020).

Zhou, G., Tang, L., Wang, T., Zhou, X. & Wang, Z. Phytochemistry and pharmacological activities of Vaccaria hispanica (Miller) Rauschert: a review. Phytochemistry Reviews 15, 813–827 (2015).

Sang, S., Lao, A., Chen, Z., Uzawa, J. & Fujimoto, Y. Chemistry and bioactivity of the seeds of Vaccaria segetalis. ACS Symposium series 859, 279–291 (2003).

Tian, M. et al. Vaccaria segetalis: A Review of Ethnomedicinal, Phytochemical, Pharmacological, and Toxicological Findings. Front Chem 9, 666280, https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2021.666280 (2021).

Yan, L. Auricular Pressing Therapy in the Treatment of Hypertension for 30 Cases. Chinese Medicine Modern Distance Education of China (2018).

Shoemaker, M., Hamilton, B., Dairkee, S. H., Cohen, I. & Campbell, M. J. In vitro anticancer activity of twelve Chinese medicinal herbs. Phytother Res 19, 649–651, https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.1702 (2005).

Chen, S. et al. Herbal genomics: Examining the biology of traditional medicines. Science 347, S27–S29, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.2015.347.6219.347_337c (2015).

Chen, S. et al. Genome sequence of the model medicinal mushroom Ganoderma lucidum. Nat Commun 3, 913, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1923 (2012).

Liu, X. et al. The Genome of Medicinal Plant Macleaya cordata Provides New Insights into Benzylisoquinoline Alkaloids Metabolism. Mol Plant 10, 975–989, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molp.2017.05.007 (2017).

Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y. & Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, i884–i890, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560 (2018).

Belton, J. M. et al. Hi-C: a comprehensive technique to capture the conformation of genomes. Methods 58, 268–276, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymeth.2012.05.001 (2012).

Dolezel, J. & Bartos, J. Plant DNA flow cytometry and estimation of nuclear genome size. Ann Bot 95, 99–110, https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mci005 (2005).

Marcais, G. & Kingsford, C. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics 27, 764–770, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btr011 (2011).

Ranallo-Benavidez, T. R., Jaron, K. S. & Schatz, M. C. GenomeScope 2.0 and Smudgeplot for reference-free profiling of polyploid genomes. Nat. Commun 11, 1432–1442, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-14998-3 (2020).

Cheng, H., Concepcion, G. T., Feng, X., Zhang, H. & Li, H. Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nat Methods 18, 170–175, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-020-01056-5 (2021).

Li, H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 34, 3094–3100, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty191 (2018).

Camacho, C. et al. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 10, 421, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-10-421 (2009).

Guan, D. et al. Identifying and removing haplotypic duplication in primary genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 36, 2896–2898, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa025 (2020).

Zeng, X. et al. Chromosome-level scaffolding of haplotype-resolved assemblies using Hi-C data without reference genomes. Nat Plants 10, 1184–1200, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-024-01755-3 (2024).

Xu, M. et al. TGS-GapCloser: A fast and accurate gap closer for large genomes with low coverage of error-prone long reads. Gigascience 9 https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giaa094 (2020).

Hu, J. A.-O. et al. NextPolish2: A Repeat-aware Polishing Tool for Genomes Assembled Using HiFi Long Reads. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 22 https://doi.org/10.1093/gpbjnl/qzad009 (2024).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324 (2009).

Rhie, A., Walenz, B. P., Koren, S. & Phillippy, A. M. Merqury: reference-free quality, completeness, and phasing assessment for genome assemblies. Genome Biol 21, 245, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-020-02134-9 (2020).

Ou, S., Chen, J. & Jiang, N. Assessing genome assembly quality using the LTR Assembly Index (LAI). Nucleic Acids Res 46, e126-e126, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky730 (2018).

Manni, M., Berkeley, M. R., Seppey, M., Simao, F. A. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO Update: Novel and Streamlined Workflows along with Broader and Deeper Phylogenetic Coverage for Scoring of Eukaryotic, Prokaryotic, and Viral Genomes. Mol Biol Evol. 38, 4647–4654, https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msab199 (2021).

Xu, Z. & Wang, H. LTR_FINDER: an efficient tool for the prediction of full-length LTR retrotransposons. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W265–W268, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkm286 (2007).

Price, A. L., Jones, N. C. & Pevzner, P. A. De novo identification of repeat families in large genomes. Bioinformatics 21, I351–I358, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bti1018 (2005).

Flynn, J. M. et al. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117, 9451–9457, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1921046117 (2020).

Tarailo-Graovac, M. & Chen, N. Using RepeatMasker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics Chapter 4, Unit 4.10, https://doi.org/10.1002/0471250953.bi0410s25 (2009).

Copetti, D. et al. RiTE database: a resource database for genus-wide rice genomics and evolutionary biology. Bmc Genomics 16, e538, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-015-1762-3 (2015).

Benson, G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 27, 573–580, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/27.2.573 (1999).

Kim, D., Paggi, J. M., Park, C., Bennett, C. & Salzberg, S. L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat Biotechnol 37, 907–915, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0201-4 (2019).

Li, H. et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352 (2009).

Kovaka, S. et al. Transcriptome assembly from long-read RNA-seq alignments with StringTie2. Genome Biol 20, 278–291, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-019-1910-1 (2019).

KJ, H., A, L., M, B. & M, S. Whole-Genome Annotation with BRAKER. Gene prediction: methods and protocols, 65–95, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-9173-0_5 (2019).

Nachtweide, S. & Stanke, M. Multi-genome annotation with AUGUSTUS. Gene prediction: methods and protocols, 139–160, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-9173-0_8 (2019).

Lomsadze, A., Burns, P. D. & Borodovsky, M. Integration of mapped RNA-Seq reads into automatic training of eukaryotic gene finding algorithm. Nucleic Acids Res 42, e119, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gku557 (2014).

Jo, S. et al. Unlocking saponin biosynthesis in soapwort. Nat Chem Biol 21, 215-226, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-024-01681-7 (2024).

Fields, P. D., Weber, M. M., Waneka, G., Broz, A. K. & Sloan, D. B. Chromosome-Level Genome Assembly for the Angiosperm Silene conica. Genome Biol Evol 15, evad192, https://doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evad192 (2023).

Li, F. et al. The chromosome-level genome of Gypsophila paniculata reveals the molecular mechanism of floral development and ethylene insensitivity. Hortic Res 9, uhac176, https://doi.org/10.1093/hr/uhac176 (2022).

Altschul, S. F. et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res 25, 3389–3402, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/25.17.3389 (1997).

Finn, R. D., Clements, J. & Eddy, S. R. HMMER web server: interactive sequence similarity searching. Nucleic Acids Res 39, W29–W37, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkr367 (2011).

Mistry, J. et al. Pfam: The protein families database in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res 49, D412–D419, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa913 (2021).

Ashburner, M. et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet 25, 25–29, https://doi.org/10.1038/75556 (2000).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 28, 27–30, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.1.27 (2000).

Chan, P. P., Lin, B. Y., Mak, A. J. & Lowe, T. M. tRNAscan-SE 2.0: improved detection and functional classification of transfer RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res 49, 9077–9096, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkab688 (2021).

Kalvari, I. et al. Non‐coding RNA analysis using the Rfam database. Current protocols in bioinformatics 62, e51, https://doi.org/10.1002/cpbi.51 (2018).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRP536556 (2024).

Zhang, C. et al. Gypsophila vaccaria isolate Hexi, whole genome shotgun sequencing project. Genbank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc:JBHZIJ000000000 (2024).

Zhang, C. et al. The annotation of Gypsophila vaccaria (Wang Bu Liu Xing). Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27636726.v1 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Science Fund for Doctoral Start-up Foundation of Hexi University (KYQD2022013; KYQD2020018), CACMS Innovation Fund (CI2021A04118, CI2021B014), President’s Fund Project of Hexi University: Innovative Research on Improving the Quality of Wine in the Characteristic Industry of Hexi Corridor (CXTD001), and Soil moisture, nutrients, and salt transport patterns and the construction of a comprehensive fertility cultivation system under the “water and fertilizer integration model” of plateau summer vegetables (2023CYZC-65).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L. and C.Z. designed the research and managed the project. J.Z. and C.Z. performed the analysis. B.Y., Y.Z., L.Y., E.W. and Y.Z. prepared the plant samples for high-throughput sequencing. J.L., C.Z. and J.Z. wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, C., Zhang, J., Yang, B. et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly and annotation of Gypsophila vaccaria. Sci Data 12, 818 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05121-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05121-6