Abstract

Traditional nighttime light (NTL) research has largely focused on urban areas, neglecting approximately 80% of Earth’s low-light or dark sky regions. This oversight may result in a significant underestimation of light pollution, especially in global protected areas that are often biodiversity hotspots. Our study employs a novel approach combining a residual neural network with a raster function model to tackle key challenges, including NTL restoration in high-latitude regions, long-term data continuity, and gap alignment across different sensor types. For the first time, we enable continuous calibration and temporal extension of global DVNL and DMSP/OLS data. Our dataset outperforms similar products by offering greater explanatory power for economic activities, enhanced temporal stability, and improved spatial distribution accuracy. Furthermore, it exhibits heightened sensitivity to subtle changes in low-light areas across global, national, urban, and protected scales, making it especially valuable for monitoring human activities and assessing environmental impacts in critical regions like World Heritage Sites, Dark Sky Preserves, and national parks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Since Elvidge C. D. et al. (1997) first used digital data to create urban lighting maps1, nighttime light (NTL) data has proven to be a key indicator of human activity, demonstrating significant research value in urbanization, economic activity monitoring, and environmental assessment. However, over the past 12 years, the annual growth rate of light pollution due to artificial lighting has reached a staggering 10%, a rate far exceeding the previously estimated 2%2, causing severe erosion of natural darkness in global Protected Areas (PAs)3.According to Combs and Miller (2023), application research based on NTL is currently concentrated on urban and high-brightness areas, with insufficient attention paid to the approximately 80% of the globe consisting of low-light areas (LLAs) or dark sky areas (DSAs), which represent only 5% of the total literature4.These areas include not only important PAs and biodiversity hotspots but also critical zones for global ecosystem quality. Against this backdrop, researchers are gradually shifting their focus from early studies on urbanization and city expansion5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12, social and population research13,14,15,16, economic activity and GDP estimation17,18,19,20, electricity supply and energy consumption21,22,23,24,25,26, environmental monitoring and pollution research27,28,29,30,31,32, and disaster emergency and recovery33,34,35, to interdisciplinary fields such as light pollution36,37,38,39 and natural resource conservation40,41,42,43,44.

However, globally consistent long-term NTL data with stable spatiotemporal structure remain scarce. Currently, authoritative global NTL datasets include DMSP/OLS V4 dataset (1992-2013), NPP/VIIRS dataset (2012-present), Black Marble (2012-present), DMSP Nighttime Lights Extension (2012-2021), and DVNL dataset (2013-2019). The DMSP/OLS dataset is the earliest NTL dataset1,45, providing global NTL information from 1992 to 2013. Despite its lower resolution (approximately 1 kilometer) and issues such as missing radiometric calibration, it has played a foundational role in early studies of urbanization and economic activity. NPP/VIIRS data, available since 201246, offer significantly improved spatial resolution (approximately 500 meters) and effectively address NTL saturation issues, greatly enhancing research depth and breadth in global urban space and industrial development47,48,49,50,51; The Black Marble dataset is a calibrated version of VIIRS data52, further improving data consistency and accuracy and being widely used across various fields53,54,55,56; Since 2013, the Earth Observation Group (EOG) has used global NTL data from DMSP/OLS series F15 and F16 satellites, collected between 1:30 AM and 4:30 AM, to generate the DMSP Nighttime Lights Extension series57. However, due to the differences in bridge time, this dataset is primarily used for studying variations in artificial light sources at different times58,59,60; Nechaev et al. (2021) utilized a residual neural network algorithm to achieve mutual calibration of DMSP and VIIRS lighting data61, extending DMSP-like NTL data to 201962,63,64. These NTL datasets provide rich data support for monitoring and analyzing socioeconomic activities globally and are important research directions in modern geographic information science and remote sensing technology.

Although nearly 97% of related research globally utilizes DMSP/OLS and NPP/VIIRS datasets4,their applications are consistently limited by spatial resolution quality and available time spans. To obtain NTL data with stable spatiotemporal dynamics, scholars worldwide have conducted extensive research addressing issues such as sensor consistency and data fusion for these datasets65,66,67,68,69, dynamic range and saturation problems69,70,71,72,73, and time series continuity57,74,75,76,77,– 78. Mainstream methods include regression models, function models (such as power functions, Sigmoid functions, and raster functions), geographically weighted regression models, machine learning, and deep learning. In recent research, Nechaev et al. (2021) utilized residual neural networks to calibrate DMSP/OLS and NPP/VIIRS NTL data and generated the DVNL (2013-2019) NTL dataset61. This is a significant and noteworthy achievement but also has issues. Although the trend fitting of DVNL 2013 aligns closely with DMSP/OLS F18 2013 and F15 2013, it did not resolve continuity issues with DMSP/OLS V4 data, leading to a significant decrease in all data (DN total, mean) in 2013 (Fig. 1B). Additionally, DVNL data was missing in high-latitude regions of the Northern Hemisphere in 2013 (Fig. 1AI-III). Zhao et al. (2022) used regression models and radiometric calibration data (SARMRC) to generate the global NTL dataset (CCNL, 1992-2013), addressing major quality issues with DMSP/OLS data79. Li and Cao (2023), building on Zhao et al.’s research, used raster functions to generate a pixel-level calibrated dataset (PCNL, 1992-2021) to improve spatiotemporal consistency80. However, the SARMRC method relies on radiometric calibration data from a limited number of years (e.g., 1996, 1999, 2000, 2003, 2004, 2006, and 2010), which may not fully reflect spatial variations in other years (e.g., 1992-1995 and 2011-2013), leading to spatiotemporal errors. Moreover, both datasets face issues such as sparsity, high noise, over-smoothing, localized error amplification, and lack of stable reference points when processing NTL data in LLAs or DSAs, potentially affecting the accurate calibration of NTL intensity changes. Li et al. (2020) used kernel density methods and Sigmoid functions to convert NPP/VIIRS data into DMSP/OLS-like data, resulting in the Harmonized DMSP/OLS/VIIRS NTL dataset (Li-NTL, 1992-2021)81. Although this method helps improve spatial consistency, the high dynamic range of NPP/VIIRS data may lead to signal compression or loss in LLAs areas. The difference in acquisition times may also affect the accuracy of LLAs data due to seasonal variations (e.g., the summer midnight sun phenomenon in high-latitude regions) (Fig. 2). Additionally, kernel density methods may cause weak NTL pixels to be overshadowed by brighter surrounding pixels, leading to an underestimation of NTL intensity in these areas. Chen et al. (2021) used cross-sensor calibration and an AE model to fuse DMSP/OLS and NPP/VIIRS data from 2000 to 2023, generating the LongNTL dataset (Chen-NTL, 2000-2022)82, demonstrating excellent spatiotemporal consistency. However, the AE model may focus more on high-intensity light source areas, leading to larger reconstruction errors and loss of some data information in LLAs or DSAs (Fig. 3). Despite the AE model’s excellent performance in many cases, there is still room for improvement when handling LLAs. Given these issues, globally consistent long-term NTL data with stable spatiotemporal dynamics, particularly those capable of sensitively reflecting dynamic changes in LLAs, still hold extensive application prospects and significant research potential.

The study aims to reassess the often-overlooked low-light areas within global NTL data, emphasizing their research value as equal to that of high-light regions. Using authoritative NTL datasets (DMSP/OLS, NPP/VIIRS, and DVNL), we have conducted pixel-level restoration, extension, alignment, and continuous calibration of long-term nighttime light data on a global scale. This shift in research focus, particularly the in-depth examination of the spatiotemporal dynamics of low-light and dark areas worldwide, offers new insights into understanding the impact of human activities on Earth’s environment. The findings are crucial not only for addressing global light pollution37 but also for advancing global sustainable development goals.

Methods

Data collection

This study used eight datasets (Table 1). The DMSP/OLS V4 dataset (https://eogdata.mines.edu/products/dmsp) is a cloud-free composite file created from all archived DMSP/OLS smoothed resolution data. The second is the DVNL dataset (https://eogdata.mines.edu/wwwdata/viirs_products/dvnl), which uses a residual U-net convolutional neural network (U-Net CNN) for cross-sensor calibration, converting NPP/VIIRS NTL data to a lower resolution to create DVNL data. The third is the Annual VNL V21 and V22 dataset (https://eogdata.mines.edu/nighttime_light/annual/) for the years 2013 and 2020-2022, released by the Earth Observation Group (EOG). This dataset employs a new method to produce global annual NPP/VIIRS NTL time series data, with the 2013 Annual VNL NTL data used to synthesize missing high-latitude NTL data, and data from other years used to synthesize DVNL data post-2019. The fourth through sixth datasets include GDP (https://api.worldbank.org/v2/en/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?downloadformat=excel), census data (https://api.worldbank.org/v2/en/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL?downloadformat=excel), and electric power consumption data (https://api.worldbank.org/v2/en/indicator/EG.USE.ELEC.KH.PC?downloadformat=excel), which are used to validate the temporal consistency of the dataset. The last two datasets are long-time series NTL datasets named Chen-NTL (10.7910/DVN/YGIVCD) and Li-NTL (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.9828827.v2), which were used to validate the spatial consistency and temporal stability of our dataset.

Framework

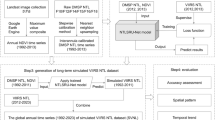

As shown in Fig. 4, our study is implemented through four steps: (1) We repair and extend the official DVNL data using a residual neural network, generating the C-DVNL (2013-2022) dataset. (2) By employing a linear trend registration approach combined with raster function models, we aligned and mosaicked the C-DVNL (2014-2022) data with the official DMSP/OLS (1992-2013) data at the pixel level, generating the LR-DVNL (1992-2022) dataset. (3) We perform an annual continuity correction on the LR-DVNL (1992-2022) data using raster functions to generate a global long-time series DMSP-like NTL data, called LRCC-DVNL (1992-2022). (4) We perform cross-comparison validation and a comprehensive accuracy assessment of our results against authoritative NTL data.

Repair and Extension of DVNL Data

In 2022, the Earth Observation Group (EOG) officially released a revised global Annual VNL V2 dataset, addressing the missing NTL data in the high-latitude regions of the Northern Hemisphere for 2013. We used the Residual U-Net code provided by Nechaev et al.61 to convert the NPP/VIIRS NTL annual data for 2013, 2020, 2021, and 2022 into corresponding DVNL NTL data. During this stage, the Residual U-Net algorithm demonstrates significant advantages in processing NTL values of LLAs through dynamic training strategies, local context modeling, and nonlinear feature learning. By employing a quantile filter to dynamically control the radiance range of training data, the network can specifically learn features of low-radiance regions (e.g., rural areas). The architectural design of the algorithm preserves local spatial information of input images through multi-level feature fusion and skip connections, enabling the network to predict values in LLAs by incorporating contextual information from surrounding pixels rather than performing simple pixel-level regression. This nonlinear processing approach significantly improves detail reconstruction capability in LLAs. Furthermore, instance normalization within residual blocks enhances the network’s learning stability for low-radiance areas. Although minor deviations exist when predicting extremely low values due to DMSP’s original data processing (which zeroes such values), the overall distribution maintains high consistency with ground-truth data. This process repaired the 2013 global high-latitude NTL data gap and extended the DVNL NTL dataset for 2020-2022. We combined the updated DVNL (2013, 2020-2022) with the official DVNL (2014-2019) to generate the Calibrated DVNL (C-DVNL) dataset from 2013-2022.

Linear trend registration of DMSP/OLS and C-DVNL data

The DVNL NTL dataset generated by Nechaev et al. (2021) using a residual neural network algorithm maintains a high interannual spatiotemporal correlation (0.96 < R2 < 0.99) with NPP/VIIRS NTL in terms of pixel radiance61, addressing the global data continuity issue of DMSP after 2013. This provides new possibilities for achieving interannual alignment between DMSP /OLS and NPP/VIIRS NTL data over longer time series. Notably, since both datasets have a minimum temporal resolution of one year, only linear trends (slope and intercept) exist between consecutive years, whether at the pixel scale or larger spatial scales. Based on this key perspective, all linear trend registrations between adjacent years in this study were implemented by individually calculating the linear variation trends between the corresponding two years.Considering the complexity and diversity of global-scale NTL variations, and referencing the “logic combination and diagnostic rule-based consistency method” proposed by Zheng et al.75, we established raster function calculation rules corresponding to five distinct NTL change trends during pixel-level registration: “constant (0 → 0 or n → n), growth in persistently lit areas (n → n+i), transition from dark to lit areas (0 → n), decline in persistently lit areas (n → n-i), and transition from lit to dark areas (n → 0)”. These rules were applied to perform segmented calculations on both the first-year and subsequent-year AC-DVNL data.

For the initial year (2014) The methodological workflow consists of: (1) applying a pixel-based linear trend registration approach to derive per-pixel trends from 2013-2014 C-DVNL data, generating pixel-level raster trend functions; followed by (2) utilizing DMSP F18 2013 data as the baseline to apply these raster trend functions to 2014 C-DVNL NTL data, thereby producing the first-year AC-DVNL dataset calibrated to align with the 2013-2014 C-DVNL linear trends. This process is computed according to Eq. (1):

If the DN values of C-DVNL 2013 and C-DVNL 2014 at pixel i are equal, the trend is considered unchanged. Regardless of the conditional value being zero, the DN value of AC-DVNL 2014 will directly take the value of DMSP 2013 at pixel i Eq. (1a). If the DN value of C-DVNL 2013 is greater than C-DVNL 2014 at pixel i, it indicates a decreasing trend and follows the slope calculation formula according to Eq. (1b). This captures both subtle and pronounced light attenuation trends, even when the DN values of C-DVNL 2014 at pixel i are 0. If the DN value of C-DVNL 2013 is less than C-DVNL 2014 at pixel i, an increasing trend is identified. Two scenarios require consideration: (1) if the DN value of C-DVNL 2013 at pixel i is 0, or the DN value of DMSP 2013 at pixel i is 0, the intercept calculation method according to Eq. (1c,d) is employed to prevent zero-value pixel outcomes. (2) otherwise, if the DN value of DMSP 2013 at pixel i is greater than 0, the standard slope calculation formula is applied (Eq. (1e)). It is important to note that to ensure the aligned AC-DVNL data remains consistent with the value range of DMSP/OLS data and to avoid extreme outliers, we applied a value range limit of [0,63] in the raster functions.

For intermediate years (2015-2022) Similarly, we implemented a nested conditional loop within the raster function (Eq. (2)). The output from the first calculation step (AC-DVNL 2014) was subsequently processed through the second calculation step, generating AC-DVNL 2015 NTL data that maintains consistency with the linear variation pattern between C-DVNL 2014 and C-DVNL 2015. This iterative process continued by feeding AC-DVNL 2015 into the second calculation step to produce AC-DVNL 2016 data, and so forth. Through this chained application of both calculation steps to annual C-DVNL 2013-2022 data, we achieved long-term temporal alignment of NTL data relative to the DMSP F18 2013 baseline, using consecutive two-year linear trend computations throughout the entire time series.

Where, n represents the year 2014, 2015..., 2021. C-DVNL (n, i) and AC-DVNL (n, i) represent the DN values of the year n and the pixel i for different datasets.

Continuity calibration of LR-DVNL data

Following official recommendations, we used the method proposed by Li et al. (2017) and Cao et al. (2020) to perform annual continuity calibration on the LR-DVNL data from 1992-2022 (including DMSP F18 2013 and AC-DVNL 2014-2022, named LR-DVNL 1992, 1993......2022)81,83, generating the global long-term Linear trend Registration Continuous Calibrated DVNL (LRCC-DVNL, 1992-2022) dataset. It is noteworthy that this method relies on an implicit assumption that NTL values are only permitted to remain stable or increase over time, while decreases are not allowed. Although this logic smoothens the time series and reduces noise, it may potentially suppress genuine declines caused by urban shrinkage, disasters, energy shortages, or socio-political events. To validate the rationality of this assumption, we selected several typical regions affected by major events for spatiotemporal data verification. The results demonstrate that the research data can effectively reflect real-world dynamics, including negative trends. Specifically, the Aleppo region in Syria exhibited a cliff-like decline in total NTL during the 2012-2015 war, with DN values plummeting from 6,591 to 6,017—the most significant drop in the city’s 31-year observation records. Yingxiu Town, the epicenter of the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake in China, showed a marked decrease in total NTL (DN values dropping from 242 to 140), followed by a gradual recovery during post-disaster reconstruction. Similarly, negative dynamics were observed in Kabul, Afghanistan between 1992 and 1995. While the methodological assumption of this study may somewhat limit the dataset’s generalizability (particularly in terms of sensitivity to negative dynamics), empirical analysis confirms its applicability for most global regions unaffected by exceptional events. The annual calibration is divided into three stages: 1992 (Eq. (3)), 1993-2021 (Eq. (4)), and 2022 (Eq. (5)), and calculated sequentially:

-

First step: Continuity calibration for the initial year (1992)

$${\rm{LRCC}} \mbox{-} {{\rm{DVNL}}}_{(1992,i)}=\left\{\begin{array}{l}0,\,{\rm{LR}} \mbox{-} {{\rm{DVNL}}}_{(1993,i)}=0\\ {\rm{LR}} \mbox{-} {{\rm{DVNL}}}_{(1992,i)},{\rm{eles}}\end{array}\right.$$(3) -

Second step: Continuity calibration for intermediate years (1993-2021)

$${\rm{LRCC}} \mbox{-} {\rm{DVNL}}{{\rm{DVNL}}}_{(n,i)}=\left\{\begin{array}{l}0,\,{\rm{LR}} \mbox{-} {\rm{DVNL}}{{\rm{DVNL}}}_{(n+1,i)}=0\\ {{\rm{LRCC}} \mbox{-} {\rm{DVNL}} \mbox{-} {\rm{DVNL}}}_{(n \mbox{-} 1,i)},{\rm{LR}} \mbox{-} {{\rm{DVNL}}}_{(n+1,i)}\\ > 0\,and\,{{\rm{LRCC}} \mbox{-} {\rm{DVNL}}}_{(n \mbox{-} 1,i)}\ge {\rm{LR}} \mbox{-} {{\rm{DVNL}}}_{(n,i)}\\ {\rm{LR}} \mbox{-} {{\rm{DVNL}}}_{(n,i)},{\rm{eles}}\end{array}\right.$$(4)Where, n represents the year 1993, 1994..., 2021. LR-DVNL (n, i) and LRCC-DVNL (n, i) represent the DN values of the year n and the pixel i for different datasets.

-

Third step: Continuity calibration for the final year (2022)

Data Records

We provide two freely accessible NTL datasets available at Harvard Dataverse84 (https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/15IKI5): (1) the corrected global C-DVNL data (2013-2022), comprising repaired 2013 data and extended 2020-2022 data, and (2) the long-term series LRCC-DVNL NTL data from 1992 to 2022. All data have been converted to the WGS 1984 Equal Earth Greenwich projection coordinate system (WKID: 8857) with a spatial resolution of 1000 meters and are stored in compressed files (20 MB to 80 MB) for each year’s data. By extracting the 7z files, the annual NTL data are provided in GeoTIFF format (30 MB to 2 GB). These data can be processed using open-source software such as QGIS. We also offer five data tables in Microsoft Excel XLSX format. The first table contains approximately 100,000 sample points and global NTL average intensity statistics for nine NTL datasets, used to validate the repair and extension results of high-latitude NTL data (Figs. 5–7). The second and third tables are used for the linear fitting analysis of the LRCC-DVNL data with GDP, POP, and EC at global and national scales (Fig. 11), and for the comparative analysis of fitting results between LRCC-DVNL, Li-NTL, and Chen-NTL datasets (Fig. 13). The last two tables are used for time series stability (ANDI) comparison analysis between different NTL data products (Fig. 14) and for analyzing spatial profile change trends of NTL data (Figs. 16–18).

Technical Validation

Repair and extension of NTL data in global high-latitude regions

To validate the repair and extension results of the C-DVNL data, we conducted spatial distribution probability and temporal trend fitting tests for the years 2013 and 2020-2022.

Spatial Distribution Probability Validation. We selected six representative regions globally for validation, including four urban areas (Los Angeles, USA; Guangzhou, China; St. Petersburg, Russia; São Paulo, Brazil) and two high-brightness areas (Maturin, Venezuela; gas flares in the Persian Gulf). To ensure sufficient valid pixels, all verification areas were expanded from urban built-up areas (over 6000 km2). The results show that the repaired C-DVNL data for 2013 maintains a high similarity in spatial distribution probability with the official DMSP data across different latitudes(0.90 ≤ R2 ≤ 0.96), with very small pixel-level errors (2.12 ≤ RMSE ≤ 6.56) (Fig. 5A–F).

Temporal Trend Consistency Validation. Due to the lack of DMSP data after 2013, we fitted the global NTL mean change trends using the extended C-DVNL data and Annual VNL V2 NTL data. As shown in Fig. 6, the two datasets exhibit a high degree of consistency in the change trends from 2013 to 2022 (Fig. 6A) and a strong correlation (R2 = 0.958, RMSE = 0.001) (Fig. 6B). Ultimately, using the Annual VNL V2 NTL data and the C-DVNL data generated by the Residual U-Net, we successfully repaired high-latitude NTL data for 2013 and effectively enhanced the global NTL mean. Specifically, Fixed DVNL2013 corrected the high-latitude data gaps in the original data (DVNL 2013.tif) (compare Fig. 7AI-III with Fig. 7BI-III), and Extended DVNL 2020-2022 updated the DVNL data for subsequent years based on the official data (Fig. 7C).

Spatial and temporal NTL data repair and extension results of C-DVNL data. Includes: (AI-III) NTL data gaps in high-latitude regions of the official DVNL data for 2013, (BI-III) data repair of C-DVNL in the problem areas for 2013, and (C) NTL data extension achieved by C-DVNL for the years 2020-2022.

However, it is important to note that there are still significant data gaps between the C-DVNL data and the official DMSP/OLS data for 2013 (Fig. 7C). Additionally, the NTL intensity of the C-DVNL data from 2013 to 2022 is generally lower than that of the DMSP data from 1992 to 2013, which does not align with the actual global NTL change trends. Therefore, addressing the data alignment issue between these two NTL datasets for 2013 is crucial.

Addressing the 2013 NTL data discontinuity issue

We used the raster function model and linear trend registration algorithm described in Section 3.2 to achieve pixel-level alignment with the official DMSP/OLS NTL data for 2013, resulting in the AC-DVNL (2013-2022) NTL data. We then conducted a statistical time series comparison between the C-DVNL and AC-DVNL. These two NTL datasets maintained almost identical change trends from 2013 to 2022 (R2 = 0.99) (Fig. 8C), with a global NTL mean increase of approximately 32.11% (Table 2). The datasets achieved seamless integration for the year 2013 (Fig. 8A,B).

We selected 100,000 random pixels from global data for the years 2014, 2018, and 2022 as validation points and conducted spatial distribution probability comparisons of the two NTL datasets at global, national, and city scales (Fig. 9). At the global scale, the linear fit values (R2) for AC-DVNL and C-DVNL in the three years were 0.91, 0.90, and 0.88, respectively, with root mean square errors (RMSE) of 1.92, 2.19, and 2.55 at a significance level (Fig. 9AI-III), demonstrating a high spatial distribution similarity of NTL intensity at the pixel level between the two datasets. At the national scale, we chose six countries (China, the United States, Brazil, India, Italy, and South Africa) as validation subsets. The accuracy was similarly high (0.93 ≤ R2 ≤ 0.99) (Fig. 9BI-VI), with no significant spatial differences. Italy had the highest accuracy (R2 = 0.99), followed by the United States (R2 = 0.97), and all other countries had accuracy above 0.93, with very small RMSE values (ranging from 1.00 to 1.83). At the smaller urban scale, the linear fit results for the total NTL intensity (sum of NTL within each city) in 3,598 major urbans globally were even better (R2 ≥ 0.97) (Fig. 9CI-III). These results indicate that from the macro global scale to the micro urban scale, the AC-DVNL data’s temporal and spatial distribution trends and intensity are very close to those of the C-DVNL data, with better fitting performance as the spatial scale decreases. The regression-aligned AC-DVNL data not only resolves the critical issue of significant data discontinuities between the official DVNL and DMSP/OLS NTL data in 2013, but also shows considerable potential for NTL data research at smaller spatial scales.

Finally, we concatenated the DMSP/OLS (1992-2013) and AC-DVNL (2013-2022) datasets with 2013 as the connecting point to generate the Linear trend Registration DVNL (LR-DVNL) from 1992-2022. Although the alignment issue between the two NTL datasets in 2013 has been preliminarily addressed, the time continuity of the LR-DVNL dataset still presents problems. These issues are evident in the linear fitting results of LR-DVNL data with global GDP (Fig. 10A), population (POP) (Fig. 10B), and electricity total consumption (EC) (Fig. 10C), with R2 values of 0.76, 0.72, and 0.74, respectively, which are lower than the fitting results of other NTL datasets79,80,81,82,85. Therefore, continuous calibration of long-term NTL data remains necessary.

Achieving time series continuity calibration for LRCC-DVNL data (1992-2022)

Using the method described in Section 3.3, we generated the LRCC-DVNL (1992-2022) NTL dataset. At the global scale, although there are slight variations in the fluctuation trends of LRCC-DVNL and AC-DVNL data from 2013 to 2022 (Fig. 11AI-II), the linear fit R2 values between the two NTL datasets and C-DVNL decreased slightly from 0.99 to 0.96 (Fig. 11AIII). However, the linear fit R2 value with global GDP increased significantly from 0.76 to 0.885 for the period 1992-2022, and the R2 values with POP and EC were also very high (0.941 and 0.929) (Fig. 11AIV-VI). At the national scale, we selected seven representative countries in the global economic development process (China, USA, India, France, South Africa, Thailand, and Italy) as validation areas. For GDP (Fig. 11BI), the R2 values for China (0.962) and India (0.910) exceeded 0.9, while the USA (0.777) and Thailand (0.78) had R2 values close to 0.8. France (0.612), South Africa (0.609), and Italy (0.616) had slightly lower R2 values but maintained good stability overall, showing a high correlation with national economic development trends. For POP (Fig. 11BII), the R2 values for South Africa (0.930), China (0.887), India (0.859), and the USA (0.807) were all above 0.80. France (0.782), Italy (0.752), and Thailand (0.677) had R2 values close to 0.7, indicating a high correlation between NTL and population changes. For EC (Fig. 11BIII), China had the highest R2 value (0.958), while India (0.908), the USA (0.808), France (0.772), and Thailand (0.778) had R2 values above 0.75. Only South Africa (0.460) and Italy (0.457) had slightly lower R2 values. These results indicate that, whether at the global or national scale, the LRCC-DVNL data, after continuity calibration, show good explanatory power and stability across multiple socioeconomic indicators.

We also identified some subtle typical features in the changes of NTL data across global spatial sections. Figure 12 visualizes the spatiotemporal distribution dynamics of LRCC-DVNL data for eight typical time sections from 1992 to 2022. Spatially, the total NTL intensity and distribution span in the Eastern Hemisphere are higher than in the Western Hemisphere (Fig. 12b). The Northern Hemisphere contributes the majority of global NTL intensity, concentrated between 22.5°N and 52.5°N, while the Southern Hemisphere has relatively lower NTL intensity (Fig. 12c). The three main NTL intensity peak regions in the Southern Hemisphere are located along the eastern coast of Brazil, the Johannesburg area of South Africa, and the eastern coast of Australia (Fig. 12aIV-VI). We selected six representative cities and their surrounding areas in regions with concentrated global NTL intensity as subfigures (Fig. 12aI-VI). Our results show more subtle changes of NTL in LLAs and DSAs around cities (Fig. 12aI-VI, the light blue dots), such as small tourist towns, low-grade roads, and rural villages (we will further compare and describe these features with other NTL data in subsequent discussions). Temporally, the NTL intensity in most regions of the world increased steadily from 1992 to 2005, but the 2008 global financial crisis had a direct impact on NTL intensity. Most regions saw little to no change in NTL intensity, and some areas experienced significant declines, which are clearly and subtly depicted (Fig. 12d–f). For example, during 2005-2015, the economically developed eastern regions of China, although affected by the financial crisis, maintained a relatively stable development trend overall (Fig. 12f, blue dashed rectangle). This stability is closely related to China’s proactive financial policies and relatively independent financial system. Meanwhile, in Central and Eastern Europe (including France, Germany, Italy, Turkey, etc.), the total NTL intensity in 2008 was significantly lower than in 2005 (Fig. 12e, light blue dashed circle). Although European NTL intensity increased significantly in 2010, countries on the EU borders such as Turkey, Romania, and Bulgaria showed significant declines in NTL intensity by 2015 compared to 2010 (Fig. 12e, dark blue dashed circle), likely due to the European debt crisis and refugee crisis in 2015. In addition, the NTL intensity in the eastern United States did not show significant changes from 2005 to 2015 but increased significantly from 2015 to 2020 (Fig. 12d, blue dashed circle). The global NTL total growth rate slowed significantly from 2020 to 2022, which aligns with the trends observed in most regions worldwide. This reflects the global economic recovery after the 2008 financial crisis and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the economy in 2020.

Spatiotemporal distribution results of global NTL intensity, including (a) global distribution of NTL intensity in 2022, NTL intensity changes over eight typical years (b) by longitude and (c) by latitude, and subtle interannual variations in (d) the eastern United States, (e) the central Europe, and (f) the eastern China, as well as (A I-VI) the NTL spatial distribution visualization of six typical cities and their surrounding areas in 2022.

Interpretation of economic activities

We conducted cross-comparisons and mutual validations of LRCC-DVNL with other global or regional NTL datasets. Comparing with the validation results of Chen-NTL (2000-2022)82, Li-NTL (1992-2018)86, Zhang-NTL(1992-2013)87,Elvidge et al., Wu-NTL (1992-2019)68 and Cao et al., our LRCC-DVNL dataset not only has a longer time span but also demonstrates better performance in terms of the coefficient of determination (R2) with various socioeconomic indicators both globally and nationally, and more stable trends (Fig. 13). For GDP (Fig. 13A-I),), the R2 values for China (0.96), the USA (0.78), India (0.91), France (0.61), South Africa (0.61), and Italy (0.62) are comparable to or exceed those of other datasets. In particular, France, South Africa, and Italy show substantial improvements, while only Thailand (0.78) has a slightly lower R2, but overall maintains the highest stability (the polylines in Fig. 13A-I). For POP (Fig. 13A-II), South Africa (0.93) and global (0.94) have the highest R2 values among all datasets, except for China (0.92), India(0.86) and Thailand (0.68), which are slightly lower. The USA (0.81), France (0.78), South Africa (0.93), and Italy (0.75) also show significant improvements in R2 (the polylines in Fig. 13A-II). For EC (Fig. 13A-III), except for India (0.91) and Thailand (0.78), which are slightly lower, China (0.96), the USA (0.82), France (0.77), South Africa (0.46), and Italy (0.46) exhibit better correlations. The improvements in R2 are particularly substantial for the USA (188%-198%), France (128%-3509%), South Africa (227%-3538%), and Italy (84%-160%).

Stability of time series

Generally, the time series curve of the Total Sum of Lights (TSOL) is stable on a large scale. To further validate the time series stability of the data, we calculated the Average of the Normalized Difference Index (ANDI) for the LRCC-DVNL, Li-NTL, and Chen-NTL datasets following the method of Li et al.80 (Fig. 14A,B). ANDI is used to quantify the likelihood of anomalous fluctuations in the data, serving as an important indicator for assessing the time series stability of NTL data products. A larger ANDI indicates a higher likelihood of anomalous fluctuations, while a smaller ANDI indicates more stable time series data. The comparison of ANDI statistics further demonstrates the time series stability of the three NTL products: (1) At the global scale, the ANDI values for LRCC-DVNL, Li-NTL, and Chen-NTL are 0.0141, 0.0411, and 0.0406, respectively, with the ANDI distribution ranges for 248 countries being [00̃.206], [00̃.484], and [000.496], respectively (Fig. 14BI-III). As shown in Fig. 14C I-VIII, the TSOL time series trends in different NTL datasets for the globe and seven selected countries indicate that the stability of Chen-NTL data is slightly better than that of Li-NTL, while our LRCC-DVNL exhibits superior spatiotemporal stability. (2) Compared to other countries, Greenland shows significant anomalous fluctuations in Chen-NTL products. However, in the LRCC-DVNL data, the ANDI for Greenland is 0.017, much lower than that of Li-NTL (0.039) and Chen-NTL (0.420). Similar characteristics are observed in Myanmar, Mongolia, and the areas around the Black Sea, suggesting that LRCC-DVNL not only enhances the stability of the time series data but also effectively captures sensitive anomalous fluctuations. (3) All three NTL products identified data fluctuations in certain countries or regions (Fig. 14AI-III, red circles), such as Afghanistan, Myanmar, North Korea, Nepal, and Papua New Guinea in Asia, and Chad, South Sudan, Kenya, and Guinea in Africa. Most of these countries are significantly affected by special events such as regional conflicts, financial crises, and political disputes, demonstrating the LRCC-DVNL data’s capability to explain global socioeconomic events effectively. (4) Due to the effective repair and extension of NTL data in the high-latitude regions of the Northern Hemisphere during the preprocessing stage, our data also exhibits better stability (Fig. 14AI-III, blue circles).

At a more refined urban spatial scale, we selected four cities (Shanghai, China; Los Angeles, USA; St. Petersburg, Russia; São Paulo, Brazil), one non-urban area (natural gas flares in Maturin, Venezuela), and one mixed area (Sicily, Italy) as validation regions. The results show that our statistical findings demonstrate better stability and explanatory power. As shown in Fig. 15, the total NTL in Shanghai exhibited a steady and rapid growth trend from 1992 to 2022, with a more significant increase after entering the 21st century compared to before 2000 (Fig. 15a). This trend is highly consistent with China’s economic development after joining the WTO in 2001, and all three NTL datasets captured a decrease in NTL intensity in 2009 (Fig. 15a, black dashed line). The total NTL in Los Angeles has remained at a high level with no significant changes over the past 30 years (Fig. 15b), consistent with its highly urbanized economic structure. In St. Petersburg, located in a high-latitude region, the total NTL has grown slowly over the past 30 years (Fig. 15c), with an inflection point in 2010 also identified by the Li-NTL and Chen-NTL datasets (Fig. 15c, green dashed line). However, Li-NTL and Chen-NTL showed values equal to or near zero in 2002, 2015, and 2018 (Fig. 15c, black dashed line), which is related to missing or incomplete NTL data for these years in high-latitude regions for the Li-NTL and Chen-NTL datasets. The results for São Paulo, Brazil (Fig. 15d), the natural gas flares in Maturin, Venezuela (Fig. 15e), and Sicily, Italy (Fig. 15f), also indicate that at the city scale, our LRCC-DVNL data show statistical trends very similar to Li-NTL and more stable than Chen-NTL.

Time series trends of total NTL for LRCC-DVNL (1992-2022), Li-NTL (1992-2021), and Chen-NTL (2000-2022) data in urban areas (a) Shanghai, China; (b) Los Angeles, USA; (c) St. Petersburg, Russia; (d) São Paulo, Brazil; non-urban area (e) natural gas flares in Maturin, Venezuela; and urban-rural mixed area (f) Sicily, Italy.

Rationalization of spatial distribution

To further validate the distribution rationality and usability of the LRCC-DVNL dataset at different spatial scales globally, we selected four highly developed cities with light saturation overflow in 2000 (Shanghai-Suzhou, China; New York, USA; Paris, France; São Paulo, Brazil) as study areas and performed spatiotemporal comparison validation with different NTL datasets. As shown in Fig. 16, our generated LRCC-DVNL data (green line) across different urban spatial profiles reflects similar distribution trends to Li-NTL and Chen-NTL data, with the positions of the peaks and troughs of the curves being largely consistent (Fig. 16A–D). Notably, our results closely match the distribution curves of the Li-NTL data and show significant improvements in local (non-saturated) regions (Fig. 16, orange line and blue dashed line). This is one of the direct reasons why the LRCC-DVNL data outperforms the Li-NTL data in fitting results with GDP, POP, and EC data. Meanwhile, comparing with the Chen-NTL data’s curve (Fig. 16, blue dashed line), although Chen-NTL data achieves light threshold upper limit breakthroughs in urban light-saturated regions due to its higher spatial resolution (500m), the AE model’s limitations significantly lower the NTL values in LLAs. For instance, in the central part of the Shanghai-Suzhou urban development axis, Kunshan (Fig. 16A-IV), the NTL value over nearly 30 km of the spatial profile is zero, whereas this area actually has a high level of urbanization with numerous industrial parks. Similar phenomena are observed in the surrounding areas of New York (Fig. 16B-IV), Paris (Fig. 16C-IV), and São Paulo (Fig. 16D-IV). Comparing the three datasets, the NTL intensity distribution of LRCC-DVNL data shows more continuity without obvious breaks or abrupt changes when transitioning from urban to non-urban areas. This smoother transition more accurately reflects the gradual decrease in light pollution in real-world conditions, demonstrating higher spatial stability and rationality.

Sensitivity of NTL data

To further evaluate the performance of the LRCC-DVNL data product in LLAs and DSAs, we selected six World Heritage Sites (WHS): Wulingyuan Scenic and Historic Interest Area of China (WLY) (Fig. 17A), Mount Etna of Italy (ME) (Fig. 17B), Great Smoky Mountains National Park of the USA (GSM) (Fig. 17C), Greater Blue Mountains Area of Australia (GBM) (Fig. 17D), Kenya Lake System in the Great Rift Valley of Kenya(KLS) (Fig. 17E) and Historic Sanctuary of Machu Picchu of Peruas (MP) (Fig. 17F) as study areas, and conducted comparative validations with Li-NTL and Chen-NTL data. As shown in (Fig. 17), the spatial distribution trends of NTL intensity in the four WHS are generally consistent across the three NTL products, with all able to identify the spatial extent of towns near the WHS and DSAs. However, there are noticeable differences in LLAs. (1) Our product shows a spatial distribution trend very similar to Li-NTL, with slightly increased NTL intensity in the peak areas of town centers while carefully preserving the spatial extent of LLAs and DSAs (Fig. 17, red line and blue dashed line). This indicates that our product does not erroneously estimate NTL intensity in the core areas of these PAs. (2) The Chen-NTL data show peak NTL intensities in neighboring towns of WLY, ME, GSM, KLS and MP that are less than 4 nWcm−2sr−2 (the unit of NPP/VIIRS NTL intensity), almost being classified as DSAs (Fig. 17A,B,C,E,F, gray dashed line). However, these three WHS receive more than 10 million visitors annually, and the peak NTL intensity in neighboring towns should not have such significant reductions due to tourism influence, likely related to the learning mechanism of the AE model. Our NTL product, on the other hand, demonstrates better stability and accuracy in these regions. (3) The Wuling Mountain Avenue (a primary tourism road) that opened at the end of 2018 runs through the WLY area, having a slight impact on WLY’s NTL intensity starting in 2019 (Fig. 18A-I, black circle). Spatial distribution results show that the overall intensity of the Chen-NTL data is very low (close to zero) (Fig. 18C-II, black circle). Although Li-NTL data recognized this change, the NTL intensity significantly decreased after 2019, weakening the NTL intensity differences between cities and roads (Fig. 18B-II, black circle). Our product sensitively and accurately captures this feature, more accurately reflecting the real socioeconomic activities in terms of temporal continuity and spatial consistency (Fig. 18A-II, black circle). In summary, our LRCC-DVNL data better captures the subtle changes of NTL in WHS and their neighboring small towns, enhancing it to a more realistic and reasonable threshold range. The LRCC-DVNL data we generated not only preserves the true spatial distribution of LLAs and DSAs, but also reflects the real NTL levels in HLAs to a certain extent.

Finally, we conducted additional validation of low-light sensitivity and tolerance for NTL values across different land cover types. Centered on Lanzhou, China, a third-tier inland city in western China with moderate urbanization levels and developed livestock industry, we delineated a 100km-diameter circular study area. This selection ensures diverse land use types (forest, grassland, barren land, wetland) within the region are potentially influenced by varying NTL intensities, providing opportunities to assess sensitivity in typical LLAs. We performed spatiotemporal resolution adjustments on land cover data for 2014, 2018, and 2022 to ensure accurate pixel DN value extraction. Validation results demonstrate significant inter-annual DN value differences across six land cover types between LRCC-DVNL and comparative datasets (Chen-NTL, Li-NTL) (Fig. 19). Mean DN distributions reflect NTL-urban space coupling degrees (Fig. 19A): while all three datasets show general rationality, Chen-NTL exhibits consistently lower values (Fig. 19AI-III), potentially underestimating regional NTL levels. Minimum DN values indicate low-light tolerance, with LRCC-DVNL and Li-NTL outperforming Chen-NTL (Fig. 19B), though our data shows lower peak values than Li-NTL (Fig. 19BI-III), suggesting absence of overfitting. Standard deviation distributions (Fig. 19C) reveal consistent trends across datasets, yet Chen-NTL displays extreme fluctuations (Fig. 19CI-III), with minimum standard deviations reaching 0 in forest and wetland areas, remaining below 4 for non-urban land types. Comparative analysis of these three metrics confirms LRCC-DVNL’s advantages in LLAs: higher dynamic range, enhanced light sensitivity, and relative rationality.

Usage Notes

The dataset can be processed and analyzed using GIS software such as QGIS or ArcGIS Pro. Researchers can also utilize programming languages like Python and R to conduct custom data processing using the provided raster calculation formulas. For further automation, the GDAL library is recommended, as it supports raster data conversion and resampling.

To maintain consistency with the historical DMSP/OLS time series data, a threshold of 63 was applied in the raster calculation formula (Eq. (1)). While this approach ensures temporal consistency, it may result in saturation overflow in most central urban areas of developed cities. Therefore, for studies focusing on human activity intensity in large and medium-sized urban areas, it is advisable to consider using additional NTL datasets or applying correction techniques.

The dataset’s spatial resolution has been reduced to 1000 meters, which means that areas smaller than 1 km2 or with a narrowest width of less than 1 km may not obtain valid NTL data. Researchers should take this limitation into account when conducting studies at a micro-scale and select data with appropriate spatial resolution based on their research needs.

Although light pollution in heavily saturated areas (DN ≥ 63) cannot be further detected, this dataset demonstrates good temporal stability (Figs. 11, 15), spatial distribution consistency (Figs. 12, 14), and correlation with economic activities (Figs. 13,16,17 and 18) in LLAs and DSAs. Therefore, this dataset is particularly suitable for environmental monitoring in global protected areas and ecologically sensitive regions. Researchers can integrate the LRCC-DVNL dataset with other NTL datasets (e.g., VIIRS/DNB and Chen-NTL82) for a more comprehensive analysis.

It is noteworthy that the interannual NTL data continuity correction method employed in this study (Eqs. (3), (4), (5)) operates under an implicit assumption that “NTL values are only permitted to remain stable or increase over time, but never decrease.” While this logic effectively smooths temporal sequences and reduces noise, it may inadvertently suppress genuine declines caused by urban shrinkage, disasters, energy shortages, or socio-political events. Although this methodological assumption could potentially constrain the dataset’s generalizability, particularly in terms of negative dynamic sensitivity, empirical analyses confirm its applicability to most global regions unaffected by exceptional events. Our ongoing research will implement a comprehensive continuity correction scheme to optimize the dataset, with updated versions being systematically released to support broader academic applications.

Code availability

The residual convolutional neural network (Residual U-Net) algorithm used in this study was developed by Nechaev et al. (2021). The complete Jupyter notebook code is freely available and can be accessed online at GitHub (https://github.com/megavaz/CNN-DMSP-generation/blob/master/notebooks/generate_dmsp.ipynb). The raster function code, which needs to be processed on geographic information software platforms such as QGIS or ArcGIS Pro, can be freely accessed at Harvard Dataverse (https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/15IKI5)by Tang et al.84.

References

Elvidge, C. D., Baugh, K. E., Kihn, E. A., Kroehl, H. W. & Davis, E. R. Mapping city lights with nighttime data from the dmsp operational linescan system. Photogrammetric Engineering and Remote Sensing 63, 727–734 (1997).

Falchi, F. & Bará, S. Light pollution is skyrocketing. Science 379, 234–235 (2023).

Gaston, K. J., Duffy, J. P. & Bennie, J. Quantifying the erosion of natural darkness in the global protected area system. Conservation Biology 29, 1132–1141 (2015).

Combs, C. L. & Miller, S. D. A review of the far-reaching usage of low-light nighttime data. Remote Sensing 15, 623 (2023).

Cao, X., Chen, J., Imura, H. & Higashi, O. A svm-based method to extract urban areas from dmsp-ols and spot vgt data. Remote Sensing of Environment 113, 2205–2209 (2009).

Imhoff, M. L., Lawrence, W. T., Stutzer, D. C. & Elvidge, C. D. A technique for using composite dmsp/ols “city lights” satellite data to map urban area. Remote Sensing of Environment 61, 361–370 (1997).

Ou, J., Liu, X., Liu, P. & Liu, X. Evaluation of luojia 1-01 nighttime light imagery for impervious surface detection: A comparison with npp-viirs nighttime light data. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 81, 1–12 (2019).

Small, C., Pozzi, F. & Elvidge, C. D. Spatial analysis of global urban extent from dmsp-ols night lights. Remote Sensing of Environment 96, 277–291 (2005).

Xue, X. et al. Delineating urban boundaries using landsat 8 multispectral data and viirs nighttime light data. Remote Sensing 10, 799 (2018).

Ye, Y. et al. Spatiotemporal characteristics of urbanization in the taiwan strait based on nighttime light data from 1992 to 2020. Remote Sensing 15, 3226 (2023).

Yu, B. et al. Urban built-up area extraction from log-transformed npp-viirs nighttime light composite data. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 15, 1279–1283 (2018).

Zhang, Q. & Seto, K. C. Mapping urbanization dynamics at regional and global scales using multi-temporal dmsp/ols nighttime light data. Remote Sensing of Environment 115, 2320–2329 (2011).

Chen, X. & Nordhaus, W. D. Using luminosity data as a proxy for economic statistics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108, 8589–8594 (2011).

Elvidge, C. D. et al. Night-time lights of the world: 1994–1995. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 56, 81–99 (2001).

Henderson, J. V., Storeygard, A. & Weil, D. N. Measuring economic growth from outer space. American economic review 102, 994–1028 (2012).

Lu, D., Tian, H., Zhou, G. & Ge, H. Regional mapping of human settlements in southeastern china with multisensor remotely sensed data. Remote Sensing of Environment 112, 3668–3679 (2008).

Bennett, M. M. & Smith, L. C. Advances in using multitemporal night-time lights satellite imagery to detect, estimate, and monitor socioeconomic dynamics. Remote Sensing of Environment 192, 176–197 (2017).

Che, M. & Gamba, P. Intra-urban change analysis using sentinel-1 and nighttime light data. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 12, 1134–1142 (2019).

Chen, J. & Li, L. Regional economic activity derived from modis data: A comparison with dmsp/ols and npp/viirs nighttime light data. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 12, 3067–3077 (2019).

Zhao, Z. et al. Analysis of the spatial and temporal evolution of the gdp in henan province based on nighttime light data. Remote Sensing 15, 716 (2023).

Hu, T. et al. Modeling the spatiotemporal dynamics of global electric power consumption (1992–2019) by utilizing consistent nighttime light data from dmsp-ols and npp-viirs. Applied Energy 322, 119473 (2022).

Liu, H., Ma, L. & Xu, L. Estimating spatiotemporal dynamics of county-level fossil fuel consumption based on integrated nighttime light data. Journal of Cleaner Production 278, 123427 (2021).

Shi, K. et al. Detecting spatiotemporal dynamics of global electric power consumption using dmsp-ols nighttime stable light data. Applied energy 184, 450–463 (2016).

Amaral, S., Câmara, G., Monteiro, A. M. V., Quintanilha, J. A. & Elvidge, C. D. Estimating population and energy consumption in brazilian amazonia using dmsp night-time satellite data. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems 29, 179–195 (2005).

Xiao, H. et al. Spatio-temporal simulation of energy consumption in china’s provinces based on satellite night-time light data. Applied Energy 231, 1070–1078 (2018).

Yang, W. et al. A new global anthropogenic heat estimation based on high-resolution nighttime light data. Scientific data 4, 1–11 (2017).

Du, X., Yu, Y., Ahenkora, B. F. & Pang, Y. Decoupling economic growth from building embodied carbon emissions in china: A nighttime light data-based innovation approach. Sustainable Production and Consumption 43, 34–45 (2023).

Lv, Q., Liu, H., Wang, J., Liu, H. & Shang, Y. Multiscale analysis on spatiotemporal dynamics of energy consumption co2 emissions in china: Utilizing the integrated of dmsp-ols and npp-viirs nighttime light datasets. Science of the Total Environment 703, 134394 (2020).

Sun, L. et al. Investigating the direct and spillover effects of urbanization on energy-related carbon dioxide emissions in china using nighttime light data. Remote Sensing 15, 4093 (2023).

Wang, G., Peng, W., Xiang, J., Ning, L. & Yu, Y. Modelling spatiotemporal carbon dioxide emission at the urban scale based on dmsp-ols and npp-viirs data: A case study in china. Urban Climate 46, 101326 (2022).

Zhang, W. et al. Effects of urbanization on airport co2 emissions: A geographically weighted approach using nighttime light data in china. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 150, 104454 (2019).

Zuo, C. et al. Correlation analysis of co2 concentration based on dmsp-ols and npp-viirs integrated data. Remote Sensing 14, 4181 (2022).

Lan, T. et al. Quantifying spatiotemporal changes in human activities induced by covid-19 pandemic using daily nighttime light data. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 14, 2740–2753 (2021).

Li, F., Liu, J., Zhang, M., Liao, S. & Hu, W. Assessment of economic recovery in hebei province, china, under the covid-19 pandemic using nighttime light data. Remote Sensing 15, 22 (2022).

Wang, C. et al. Impacts of covid-19 on urban networks: Evidence from a novel approach of flow measurement based on nighttime light data. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems 107, 102056 (2024).

Beeco, J. A. et al. Support for management actions to protect night sky quality: Insights from visitors to state and national park units in the us. Journal of Environmental Management 345, 118878 (2023).

Levin, N. et al. Remote sensing of night lights: A review and an outlook for the future. Remote Sensing of Environment 237, 111443 (2020).

Riza, L. S. et al. Data analysis techniques in light pollution: A survey and taxonomy. New Astronomy Reviews 95, 101663 (2022).

Yan, Z. & Tan, M. Changes in light pollution in the pan-third pole’s protected areas from 1992 to 2021. Ecological Informatics 75, 102016 (2023).

Mård, J., Di Baldassarre, G. & Mazzoleni, M. Nighttime light data reveal how flood protection shapes human proximity to rivers. Science Advances 4, eaar5779 (2018).

Shi, K., Huang, C., Chen, Y. & Li, L. Remotely sensed nighttime lights reveal increasing human activities in protected areas of china mainland. Remote Sensing Letters 9, 467–476 (2018).

Xu, P., Wang, Q., Jin, J. & Jin, P. An increase in nighttime light detected for protected areas in mainland china based on viirs dnb data. Ecological Indicators 107, 105615 (2019).

Zhao, Y. et al. Effects of human activity intensity on habitat quality based on nighttime light remote sensing: A case study of northern shaanxi, china. Science of the Total Environment 851, 158037 (2022).

Jin, X., Li, X., Feng, Z., Wu, J. & Wu, K. Linking ecological efficiency and the economic agglomeration of china based on the ecological footprint and nighttime light data. Ecological Indicators 111, 106035 (2020).

Baugh, K., Elvidge, C. D., Ghosh, T. & Ziskin, D. Development of a 2009 stable lights product using dmsp-ols data. Proceedings of the Asia-Pacific Advanced Network 30, 114 (2010).

Elvidge, C. D., Zhizhin, M., Ghosh, T., Hsu, F.-C. & Taneja, J. Annual time series of global viirs nighttime lights derived from monthly averages: 2012 to 2019. Remote Sensing 13, 922 (2021).

Chen, H., Zhang, X., Wu, R. & Cai, T. Revisiting the environmental kuznets curve for city-level co2 emissions: based on corrected npp-viirs nighttime light data in china. Journal of Cleaner Production 268, 121575 (2020).

Chen, Z., Xu, W. & Zhao, Z. The assessment of industrial agglomeration in china based on npp-viirs nighttime light imagery and poi data. Remote Sensing 16, 417 (2024).

Liu, S., Shi, K. & Wu, Y. Identifying and evaluating suburbs in china from 2012 to 2020 based on snpp–viirs nighttime light remotely sensed data. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 114, 103041 (2022).

Yuan, M., Li, X., Li, D. & Wu, J. An analysis of environmental effect on viirs nighttime light monthly composite data at multiple scales in china. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 16, 825–840 (2022).

Zhou, Y., Li, C., Zheng, W., Rong, Y. & Liu, W. Identification of urban shrinkage using npp-viirs nighttime light data at the county level in china. Cities 118, 103373 (2021).

Román, M. O. et al. Nasa’s black marble nighttime lights product suite. Remote Sensing of Environment 210, 113–143 (2018).

Li, T. et al. Continuous monitoring of nighttime light changes based on daily nasa’s black marble product suite. Remote Sensing of Environment 282, 113269 (2022).

Martinez, J. F., MacManus, K., Stokes, E. C., Wang, Z. & de Sherbinin, A. Suitability of nasa’s black marble daily nighttime lights for population studies at varying spatial and temporal scales. Remote Sensing 15, 2611 (2023).

Xiao, Q. et al. Artificial light at night and social vulnerability: An environmental justice analysis in the us 2012–2019. Environment international 178, 108096 (2023).

Zhang, Y., Li, X., Huang, J., Guan, H. & Huang, H. A novel framework for urban land cover change detection with nasa’s black marble nighttime lights product. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 61, 1–9 (2023).

Ghosh, T. et al. Extending the dmsp nighttime lights time series beyond 2013. Remote Sensing 13, 5004 (2021).

Bluhm, R. & McCord, G. C. What can we learn from nighttime lights for small geographies? measurement errors and heterogeneous elasticities. Remote Sensing 14, 1190 (2022).

Joseph, I.-L. The effect of natural disaster on economic growth: Evidence from a major earthquake in haiti. World Development 159, 106053 (2022).

Zhang, X. & Gibson, J. Using multi-source nighttime lights data to proxy for county-level economic activity in china from 2012 to 2019. Remote Sensing 14, 1282 (2022).

Nechaev, D. et al. Cross-sensor nighttime lights image calibration for dmsp/ols and snpp/viirs with residual u-net. Remote Sensing 13, 5026 (2021).

Elvidge, C. D. et al. Fifty years of nightly global low-light imaging satellite observations. Frontiers in Remote Sensing 3, 919937 (2022).

Huang, R., Wu, W. & Yu, K. Building consistent time series night-time light data from average dmsp/ols images for indicating human activities in a large-scale oceanic area. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 114, 103023 (2022).

Zhou, Y., He, X. & Zikirya, B. Boba shop, coffee shop, and urban vitality and development-a spatial association and temporal analysis of major cities in china from the standpoint of nighttime light. Remote Sensing 15, 903 (2023).

Hsu, F.-C., Baugh, K. E., Ghosh, T., Zhizhin, M. & Elvidge, C. D. Dmsp-ols radiance calibrated nighttime lights time series with intercalibration. Remote Sensing 7, 1855–1876 (2015).

Ma, J., Guo, J., Ahmad, S., Li, Z. & Hong, J. Constructing a new inter-calibration method for dmsp-ols and npp-viirs nighttime light. Remote Sensing 12, 937 (2020).

Tu, Y. et al. A novel cross-sensor calibration method to generate a consistent night-time lights time series dataset. International Journal of Remote Sensing 41, 5482–5502 (2020).

Wu, Y., Shi, K., Chen, Z., Liu, S. & Chang, Z. Developing improved time-series dmsp-ols-like data (1992–2019) in china by integrating dmsp-ols and snpp-viirs. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 60, 1–14 (2021).

Zheng, Q., Weng, Q. & Wang, K. Developing a new cross-sensor calibration model for dmsp-ols and suomi-npp viirs night-light imageries. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 153, 36–47 (2019).

Huang, X., Shi, K., Cui, Y. & Li, Y. A saturated light correction method for dmsp-ols nighttime stable light data by remote and social sensing data. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 14, 1885–1894 (2021).

Ma, L., Wu, J., Li, W., Peng, J. & Liu, H. Evaluating saturation correction methods for dmsp/ols nighttime light data: A case study from china’s cities. Remote Sensing 6, 9853–9872 (2014).

Shen, Z., Zhu, X., Cao, X. & Chen, J. Measurement of blooming effect of dmsp-ols nighttime light data based on npp-viirs data. Annals of GIS 25, 153–165 (2019).

Zhang, Q., Zheng, Z., Wu, Z., Cao, Z. & Luo, R. Using multi-source geospatial information to reduce the saturation problem of dmsp/ols nighttime light data. Remote Sensing 14, 3264 (2022).

Chakraborty, S. & Stokes, E. C. Adaptive modeling of satellite-derived nighttime lights time-series for tracking urban change processes using machine learning. Remote Sensing of Environment 298, 113818 (2023).

Zheng, Z. et al. Logic combination and diagnostic rule-based method for consistency assessment and its application to cross-sensor calibrated nighttime light image products. Remote Sensing of Environment 318, 114598 (2025).

Gibson, J. & Boe-Gibson, G. Nighttime lights and county-level economic activity in the united states: 2001 to 2019. Remote Sensing 13, 2741 (2021).

Zhao, N., Liu, Y., Cao, G., Samson, E. L. & Zhang, J. Forecasting china’s gdp at the pixel level using nighttime lights time series and population images. GIScience & Remote Sensing 54, 407–425 (2017).

Zou, Y. et al. Monitoring urban clusters expansion in the middle reaches of the yangtze river, china, using time-series nighttime light images. Remote Sensing 9, 1007 (2017).

Zhao, C., Cao, X., Chen, X. & Cui, X. A consistent and corrected nighttime light dataset (ccnl 1992–2013) from dmsp-ols data. Scientific Data 9, 424 (2022).

Li, S. et al. Developing a pixel-scale corrected nighttime light dataset (pcnl, 1992–2021) combining dmsp-ols and npp-viirs. Remote Sensing 15, 3925 (2023).

Li, X. & Zhou, Y. A stepwise calibration of global dmsp/ols stable nighttime light data (1992–2013). Remote Sensing 9, 637 (2017).

Chen, Z. et al. An extended time-series (2000-2023) of global npp-viirs-like nighttime light data. Harvard Dataverse https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/YGIVCD (2020).

Cao, Z., Wu, Z., Mi, S. & Yang, K. A method for classified correction of stable dmsp/ols nighttime light imagery across china. J. Earth Inf. Sci 22, 246–257 (2020).

Tang, h., Zhong, y. & Xia, h. Lrcc-dvnl: long-term series (1992-2022) of global nighttime light dataset focusing on low-light areas. Harvard Dataverse https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/15IKI5 (2024).

Li, X., Zhou, Y., Zhao, M. & Zhao, X. A harmonized global nighttime light dataset 1992–2018. Scientific data 7, 168 (2020).

Li, X., Zhou, Y., zhao, M. & Zhao, X. Harmonization of dmsp and viirs nighttime light data from 1992-2018 at the global scale. figshare. Dataset. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.9828827.v2 (2020).

Zhang, Q., Pandey, B. & Seto, K. C. A robust method to generate a consistent time series from dmsp/ols nighttime light data. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 54, 5821–5831 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Earth Observation Group for providing the original DMSP/OLS, NPP/VIIRS, and DVNL NTL data. We also want to express our gratitude to Christopher Elvidge, Dmitry Nechaev, and other pioneers in the field for their outstanding contributions. This study was supported by National Forestry and Grassland Administration Sub-organization(Grant no. 210404314). The authors had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.T. designed and developed the methodology and software, performed analysis and validation, and wrote the paper. Y.D.Z. developed the methodology, performed validation, and reviewed the paper. J.Y.D. supported and designed the study and wrote the paper. H.L.X. performed the validation and wrote the paper. J.W. supported and supervised the study. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, H., Zhong, Y., Deng, J. et al. Global nighttime light dataset from 1992 to 2022 with focus on low-light areas. Sci Data 12, 982 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05246-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05246-8