Abstract

Genome assembly and structural variation analysis of strawberry varieties are essential for understanding the genetic basis of fruit quality traits, such as fruit texture, organic acid content and aroma. In this study, we employed PacBio HiFi reads and Hi-C sequencing to generate a haplotype-resolved chromosome-level genome assembly of the improved strawberry cultivar ‘Yuexin’, which was selected from the crossing of ‘0362’ (‘Camarosa’ × ‘Akihime’) × ‘Sachinoka’. The assembly sizes of the primary assembly and two haplotypes were 875.84 Mb, 867.93 Mb and 823.17 Mb, with N50 length of 27.6 Mb, 27.3 Mb and 27.6 Mb respectively. Comprehensive genome comparison with its parent, cultivar ‘Camarosa’, identified numerous structural variants, which are positioned in the promoter or gene body regions. Some of these genes are involved in pathways related to cell wall, malate metabolism and fruit aroma. This dataset comprises the assembled genome sequence, annotations, and identified structural variants, providing new insights into the genetic basis of improved fruit quality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Cultivated strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch.) has substantial economic importance as one of the most widely consumed fruits globally. Based on FAO reports, the worldwide production of strawberries exceeded 9.18 million tonnes in 2021(https://www.fao.org). Packed with vitamins, especially vitamin C, manganese, and antioxidants, strawberries also offer a range of health benefits. The Fragaria genus comprises 22 wild species with diverse ploidy levels, ranging from diploid (2n = 2x = 14) to decaploid (2n = 10x = 70). Cultivated strawberry is a complex allo-octoploid (2n = 8x = 56) originated from the natural interspecific hybridization of two octoploid species, Fragaria chiloensis and Fragaria virgniana, in 18th-century Europe1,2. Advances in genomics have enabled scientists to better understand and manipulate traits, building on a history of selective breeding to produce varieties that can withstand environmental challenges and appeal to diverse markets3. Initial genome sequencing efforts focused on the Fragaria vesca (wild strawberry) due to its simpler diploid structure4. One of the main breakthroughs came in 2019 with the release of the first chromosome-level genome of F. × ananassa cv. Camarosa5. With this reference genome in hand, scientists have begun to map genes responsible for desirable agronomic traits, such as flavor profiles, color, firmness, and shelf life. In recent years, driven by advances in sequencing technology, more and more octoploid strawberry genomes have been sequenced and published5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13. The genomes of cultivars such as ‘Reikou’6, ‘Wongyo 3115’7, and ‘FL 15.89-25’8 have provided valuable resources for genetic and genomic studies. Notably, haplotype-resolved assemblies of cultivars such as ‘Benihoppe’9, ‘Yanli’10, ‘Florida Brilliance’11, ‘Chulian’12 have captured extensive heterozygosity and haplotype diversity, enabling more accurate analysis of allelic variations and their functional impacts. The fully phased genome of the ‘EA78’ cultivar13 has advanced our understanding of centromeric satellite evolution in octoploid strawberry. These advancements in strawberry genomics have not only enhanced our understanding of genome structure and evolution but also provided powerful tools for improving strawberry breeding and fruit quality.

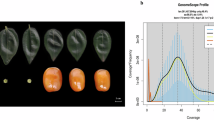

Strawberry breeding has undergone considerable advancements over the past few centuries, shaping the fruit to meet specific agricultural, commercial, and consumer demands. Cultivar ‘Camarosa’ is a common variety in the U.S.A., producing large, firm and sweet berries. Cultivar ‘Yuexin’ has emerged as a primary variety in Zhejiang Province China, notable for its superior fruit characteristics, along with its good storage capabilities and disease resistance14. ‘Yuexin’ was selected from the crossing of ‘0362’ (‘Camarosa’ × ‘Akihime’) × ‘Sachinoka’14, and thus has a close genetic background to ‘Camarosa’. However, the fruits of ‘Yuexin’ are softer and more aromatic than ‘Camarosa’. Comparing the genome of ‘Yuexin’ with ‘Camarosa’ could shed light on the genetic variants underlying the phenotypic variation in fruit quality. Furthermore, in the era of pan-genomics, a single reference genome is no longer sufficient to capture the full genetic diversity within a species. The construction of a pan-genome, which integrates genomic information from multiple individuals, has become essential for a comprehensive understanding of species-level variation. ‘Yuexin’ genome assembly would help to enrich and expand the collective pan-genome framework.

In this study, we present a high-quality haplotype-resolved chromosome-level genome assembly of strawberry cultivar ‘Yuexin’ combining PacBio long-read, Illumina short-read, and Hi-C sequencing technologies. The assembly exhibits high contiguity and completeness, providing a solid foundation for subsequent comparative genomic analyses. Through genome comparison analysis, we identified numerous structural variations between ‘Yuexin’ and ‘Camarosa’. This work provides a valuable genomic resource for strawberry breeding.

Methods

Sample collection

The strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa) cultivar ‘Yuexin’ (2n = 8x = 56) was used for genome sequencing. Plants were grown in the greenhouse of the Zijingang Campus at Zhejiang University (Zhejiang, China). Young and tender leaves were ground with liquid nitrogen and stored in a −80 °C freezer for PacBio HiFi (High fidelity), Hi-C and Illumina library preparation and sequencing. ‘Yuexin’ receptacles at the red stage were collected for RNA-Seq (RNA sequencing). The receptacles were also ground with liquid nitrogen and stored in a −80 °C freezer. Three biological replicates were performed with each replicate pooled from 12 receptacles. The sequencing services were performed by Biomarker Technologies (Beijing, China).

DNA extraction and sequencing

The genomic DNA (gDNA) was isolated from young leaf tissue of ‘Yuexin’ using the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method15. The quantity and quality of the extracted DNA was assessed using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) and a Qubit fluorometer (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA), respectively. The high-quality DNA was then fragmented by g-TUBE (Covaris) and used to prepare the sequencing library using the SMRTbell Template Prep Kit according to the manufacturer’s (PacBio, Menlo Park, CA, USA) instructions. Three SMRT cells were performed on the PacBio Sequal II platform, generating a total of 1,142.25 Gb of subreads. After calling consensus sequences from subreads, a total of 73.25 Gb of HiFi reads were generated (Table 1). A high-throughput chromosome conformation capture (Hi-C) library was prepared following the proximo Hi-C protocol (Phase Genomics, Seattle, WA, USA) and sequenced using the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), resulting a total of 95.4 Gb paired-end reads (Table 1). For short-read sequencing, one paired-end library was constructed using the Illumina TruSeq DNA sample preparation kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions, and sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform, which generated a total of 55.89 Gb of raw data (Table 1).

RNA extraction and sequencing

Transcriptome sequencing was conducted to aid gene prediction. The ‘Yuexin’ receptacles were ground with liquid nitrogen and 50 mg samples were used to extract total RNA using the CTAB15 method. The quantity and quality of RNA was assessed using NanoDrop (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) and Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies Inc., CA, USA). The library was constructed using the Dual-mode mRNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (Hieff NGS Ultima) and subsequently sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). A total of 21.54 Gb paired-end reads were generated (Table 1). RNA-Seq data from other tissues of cultivated strawberry were downloaded from NCBI SRA databases (Supplementary Table S1).

De novo genome assembly

Before assembling the genome, we first estimated the genome size using the k-mer method described in Chen et al.16, i.e. “Estimated genome size (bp) = total number of k-mer/peak value of k-mer depth distribution”. Illumina reads were performed to remove adapters and low quality sequences by Trimmomatic v0.3617. The frequency of K-mers was extracted using Jellyfish v2.2.1018, and the genome size was estimated to be 845.38 Mb with a heterozygosity rate of 0.86% (Supplementary Figure S1 and Table S2).

We then utilized PacBio HiFi reads and Hi-C reads for de novo genome assembly and haplotype phasing using Hifiasm version 0.16.1-r37519 in ‘Hi-C integrated’ mode. The resulting contigs were compared against the NCBI NT database (nonredundant comprehensive nucleotide database) using BLAST + v2.10.020 with the parameters “–dust yes –max_target_seqs. 10 –evalue 1e–5 –outfmt ‘6 qseqid sseqid pident mismatch gapopen qstart qend sstart send evalue staxids sscinames sskingdoms’“ to identify contamination based on taxonomy. Sequences that had over 80% coverage with non-plant sequences were removed. The remaining contigs were then compared with themselves using BLAST + v2.10.020. Contigs with over 80% identity and 80% coverage to other contigs were considered as redundant and removed. Finally, we corrected potential sequence errors using uniquely mapped short reads by Pilon v1.2421. Both the primary assembly and the haplotype assemblies were corrected for three rounds. The primary assembly contained 1,331 contigs with a total size of 835.67 Mb (Table 2). Haplotype 1 contained 1,441 contigs with a total size of 834.03 Mb and Haplotype 2 has 643 contigs with a total size of 801.82 Mb (Table 2). The N50 length of the primary assembly, Haplotype 1, and Haplotype 2 were 17.99 Mb, 17.3 Mb and 17.44 Mb, respectively (Table 2).

The clean Hi-C reads was used to anchor the contigs into the pseudo-chromosomes. First, the Hi-C reads were aligned to the draft assembly using Juicer v1.622 with default parameters. Paired reads mapped to different contigs were used for the Hi-C associated scaffolding. Self-ligated, non-ligated, and other invalid reads were filtered out. We then applied 3D-DNA version 18011423 to order and orient the clustered contigs, and used JUICEBOX24 (https://github.com/aidenlab/Juicebox, v1.1108) to adjust and correct chromosome manually (Fig. 1A, Supplementary Figure S2). Finally, we anchored 782.26 Mb of sequences into 28 pseudo-chromosomes with N50 length of 27.62 Mb, representing 93.61% of the total genome size (Fig. 2). A total of 39 gaps with length of 18,407 bp were remained in the assembly (Fig. 2). Employing the same pipeline, we anchored 781.17 Mb and 775.56 Mb of sequences to the pseudo-chromosomes for the two haplotypes, respectively (Table 2). Since the cultivated strawberry is allo-octoploid (2n = 8x = 56), we applied SubPhaser v1.2.525 to phase the subgenomes. SubPhaser uses repetitive kmers as the “differential signatures” to phase subgenomes, which does not depend on the diploid progenitors. Using Subphaser, we successfully phased ‘Yuexin’ genome assembly into four subgenomes (Supplementary Table S3, Supplementary Figure S3).

Genome assembly of ‘Yuexin’. (A) Hi-C interactive heatmap of ‘Yuexin’ primary assembly. (B) Circular view of the chromosome organization of the ‘Yuexin’ genome. Genomic features indicated from outer to inner layers in sliding window of 100 kb. (a) The 28 pseudochromosomes; (b) gene density; (c) repeat density; (d) GC content, (e) syntenic link among homologous chromosomes.

Annotation of repetitive elements

We identified miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements (MITEs) in the ‘Yuexin’ genome assembly using MITE-Hunter26, and collected long terminal repeat (LTR) sequences using LTRharvest27 and filtered by LTRdigest28 as well as GenomeTools version 1.5.929. We then generated a de novo TE (transposable elements) library built by RepeatModeler version 2.0.330. We subsequently employed the ProtExluder.pl script to exclude the protein coding regions in these repeat sequences. Finally, the sequences from MITEs, LTRs and de novo TE libraries were combined and used as the input library of Repeatmasker version 4.1.2-p131 to annotate the repeats in the ‘Yuexin’ assembly. Overall, 51.25% of the ‘Yuexin’ primary genome was identified as repetitive elements (Table 3). The most abundant repeats were LTR, which occupied 22.92% of the genome.

Protein-coding gene annotation

The protein-coding genes in the ‘Yuexin’ genome were annotated using the automated pipeline MAKER version 3.1.232. This process integrated the results from ab initio gene predictions with experimental gene evidence and homologous genes to produce a final consensus gene set. The experimental evidences included RNA-Seq in this study and those downloaded from NCBI SRA database (Supplementary Table S1). Raw RNA-Seq reads were processed to remove adapter and low-quality sequences using Trimmomatic17 with the following parameters: SLIDINGWINDOW:4:15; LEADING:3; TRAILING:3; MINLEN:36. The RNA-Seq reads were mapped to the soft-masked ‘Yuexin’ genome using HISAT233 and assembled by StringTie v2.2.134 with default parameters. For the homologous gene evidences, we downloaded reference proteomic sequences of four cultivated strawberry varieties from GDR (https://www.rosaceae.org/), including Benihoppe9, Camarosa v1.a235, Royal Royce, and FL 15.89-2511. We also adopted SwissProt protein sequences downloaded from UniProt protein database (https://www.uniprot.org). All the protein sequence evidences were aligned to ‘Yuexin’ genome assembly using Spaln36 with the default parameters. MAKER ran a battery of trained gene predictors, including BRAKER v2.1.437, AUGUSTUS38 and GeneMark-ES39, and then integrated the RNA and protein evidences to produce evidence-based predictions. In total, 110,776 protein coding genes were predicted in the ‘Yuexin’ primary genome (Table 4). Liftoff v1.6.340 was used to generate the gene annotation of two haplotype assemblies, resulting in 109,798 and 109,706 protein-coding genes, respectively (Table 4).

For functional annotation of the protein-coding genes, we used DIAMOND41 to compare all the proteins with a series of protein databases included the SwissProt database and the reference proteomes of several Rosaceae species, including peach, pear, cherry, apricot, as well as Arabidopsis thaliana and Solanum lycopersicum. The readable function descriptions were assigned to ‘Yuexin’ genes by AHRD (Automated Assignment of Human Readable Descriptions, https://github.com/groupschoof/AHRD) Version 3.3.3. In addition, we used InterProScan Version 5.52–86.042 to annotate the functional protein domains and Gene Ontology (GO) terms for each gene. The pathways in which the genes might be involved were annotated using the eggNOG-mapper43. As a result, 88.76% of the genes were assigned functional annotation (Table 5).

Non-coding RNA annotation

Four types of non-coding RNAs, including transfer RNA (tRNA), microRNA (miRNA), ribosomal RNA (rRNA) and small nuclear RNA (snRNA) were identified through structural features and homology assignments. tRNAs and their secondary structures were predicted by TRANSCAN-SE version 2.0.1144 with default parameters. rRNAs were predicted by Barrnap45 version 0.9. miRNAs and snRNAs were annotated by homology search against the Rfam database (release 14.9)46 using Infernal47 version 1.1.4. A total of 8,248 ncRNAs (1,482 rRNAs, 9,172 tRNAs, 444 miRNAs and 1,341 snRNAs) were identified in the ‘Yuexin’ genome (Supplementary Table S4).

Structural variations between ‘Yuexin’ and ‘Camarosa’ genomes

We compared the ‘Yuexin’ genome assembly with ‘Camarosa’ genome and identified structural variations (SV) between them. In brief, the ‘Yuexin’ assembly was aligned to ‘Camarosa’ genome by minimap2 v2.1748 with parameter ‘-ax asm5 -eqx’. Structural variants were then identified using SyRI v1.6.33749 with default parameters, and plotted by Plotsr v1.1.13850 (Fig. 2).

A total of 2,619,186 SNPs, 416,945 small Indels (<50 bp) and 26,485 SVs (>50 bp) were detected in the ‘Yuexin’ genome. Additionally, we identified 1,567 and 14,053 duplications in ‘Yuexin’ and ‘Camarosa’ genomes, respectively. The majority of SVs (70.0%) were located in intergenic regions, with 26.6% positioned within 2 kb upstream of 5,590 protein-coding genes. Only 29.9% SVs were located in gene bodies, affecting a total of 11,414 protein coding genes. In particular, 23 protein coding genes, whose functions were involved in the cell wall, aroma and organic acid pathway, harbor SVs in either promoter or gene body regions (Supplementary Table S5).

Data Records

The raw sequencing data (Illumina reads, PacBio HiFi reads, and Hi-C reads) that were used for the genome assembly have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under BioProject number PRJNA1032212. The RNA-Seq for receptacle at red stage are available under accession number SRR287644651, SRR2857644752 and SRR2857644853. The genomic PacBio sequencing data can be found in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database under the accession numbers SRR2857644954, SRR2857645055 and SRR2857645156. Hi-C sequencing data refers to accession numbers SRR2857645257 in the SRA database. The genomic Illumina sequencing data are available under accession number SRR2857645358.

The final genome assembly was deposited in the GenBank under the accession number: GCA_045269825.159, and the haplotype-1 and haplotype-2 genome assembly were deposited in GenBank under the accession: GCA_045516675.160 and GCA_045516685.161. The genome annotation GFF is available under accession number GWHERLF0000000062 in the National Genomics Data Center (NGDC).

Moreover, the gene structure annotation files of ‘Yuexin’ genome and the variant call format (VCF) file containing genomic variations identified between ‘Yuexin’ and ‘Camrosa’ strawberry cultivars have been deposited at the Figshare63 database.

Technical Validation

High quality of genome assembly

We employed several approaches to assess the completeness of ‘Yuexin’ genome assembly. We first used BUSCO to compare the genome assembly against the embryophyta_odb10 core gene database. Results revealed that 99.07% of BUSCO genes were successfully detected, suggesting high quality and completeness (Table 2). We then aligned the genome sequencing reads to the assembly. The PacBio HiFi reads and Illumina short reads were aligned to the assembly using Minimap2 v2.1748 and BWA v0.7.17-r118864, respectively. More than 99.5% of reads were successfully mapped back to the ‘Yuexin’ genome assembly (Supplementary Table S6). We also mapped RNA-Seq reads to the ‘Yuexin’ genome using HISAT2 v2.1.033 and the mapping rate of ‘Yuexin’ receptacle RNA-Seq was higher than 97% (Supplementary Table S1). For the assessment of continuity, LTR Assembly Index (LAI) was calculated using LTR_retriever v2.9.065 with default parameters and the result was 15.8 (Table 2). Furthermore, the kmer-based consensus quality value (QV) was reported as 47.1 by Merqury v1.366 with 19-mers extracted from the Illumina reads, revealing a high single-base accuracy for the ‘Yuexin’ genome assembly (Table 2). All these features together indicate that the ‘Yuexin’ genome assembly in this study is of high quality.

Validation of structural variants by PCR amplification

We performed experimental validation of the SVs between ‘Yuexin’ and ‘Camarosa’ using PCR amplification across 6 randomly selected SVs. For each candidate SV, we designed flanking primers bridging the SV region (Supplementary Table S7). PCR amplification was performed using Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific), followed by agarose gel electrophoresis to assess the product sizes. SVs were validated as the PCR product size matched the predicted fragment size of SVs (Supplementary Figure S4).

Code availability

All software and pipelines were executed according to the manuals and protocols of the published bioinformatics tools. The versions and code/parameters of software have been described in Methods.

References

Hancock, J. F. Strawberries. (CABI Publishing, 1999).

Darrow, G. M. The Strawberry: History, Breeding and Physiology. (Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1996).

Whitaker, V. M. et al. A roadmap for research in octoploid strawberry. Hortic Res. 7, 33 (2020).

Shulaev, V. The genome of woodland strawberry (Fragaria vesca). Nat Genet. 43, 109–116 (2011).

Edger, P. P. et al. Origin and evolution of the octoploid strawberry genome. Nat Genet. 51, 541–547 (2019).

Shirasawa, K. et al. Whole genome assembly in a Japanese strawberry cultivar, ‘Reikou’, and comparison with wild Fragaria genomes. Acta Hortic. 175–180 (2021).

Lee, H. E. et al. Chromosome level assembly of homozygous inbred line ‘Wongyo 3115’ facilitates the construction of a high-density linkage map and identification of QTLs sssociated with fruit firmness in octoploid strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa). Front Plant Sci. 12, 696229 (2021).

Fan, Z. et al. A multi-omics framework reveals strawberry flavor genes and their regulatory elements. New Phytol. 236, 1089–1107 (2022).

Song, Y. et al. Phased gap-free genome assembly of octoploid cultivated strawberry illustrates the genetic and epigenetic divergence among subgenomes. Hortic Res. 11, uhad252 (2024).

Mao, J. et al. High-quality haplotype-resolved genome assembly of cultivated octoploid strawberry. Hortic Res. 10, uhad002 (2023).

Han, H. et al. A telomere-to-telomere phased genome of an octoploid strawberry reveals a receptor kinase conferring anthracnose resistance. Gigascience. 14, giaf005 (2025).

Zhang, J., Liu, S., Zhao, S., Nie, Y. & Zhang, Z. A telomere-to-telomere haplotype-resolved genome of white-fruited strawberry reveals the complexity of fruit colour formation of cultivated strawberry. Plant Biotechnol J. 23, 78–80 (2025).

Jin, X. et al. A fully phased octoploid strawberry genome reveals the evolutionary dynamism of centromeric satellites. Genome Bio. 26, 17 (2025).

Zhang, Y. H. et al. Yuexin’, a new strawberry cultivar with high quality and disease resistance. Journal of Fruit Science. 32, 1294–1296 (2015).

Inglis, P. W. et al. Fast and inexpensive protocols for consistent extraction of high-quality DNA and RNA from challenging plant and fungal samples for high-throughput SNP genotyping and sequencing applications. PLoS One 13, e0206085 (2018).

Chen, W. et al. Estimation of the whitefly Bemisia tabaci genome size based on k-mer and flow cytometric analyses. Insects. 6, 704–715 (2015).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 30, 2114–2120 (2014).

Marçais, G. & Kingsford, C. A. Fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics. 27, 764–770 (2011).

Cheng, H. et al. Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nat Methods. 18, 170–175 (2021).

Camacho, C. et al. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics. 10, 421 (2009).

Walker, B. J. et al. Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS One 9, e112963 (2014).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicer provides a one-click system for analyzing loop-resolution Hi-C experiments. Cell Syst. 3, 95–98 (2016).

Dudchenko, O. et al. De novo assembly of the Aedes aegypti genome using Hi-C yields chromosome-length scaffolds. Science. 356, 92–95 (2017).

Robinson, J. T. et al. Juicebox.js provides a cloud-based visualization system for Hi-C data. Cell Syst. 6, 256–258.e1 (2018).

Jia, K. H. et al. SubPhaser: a robust allopolyploid subgenome phasing method based on subgenome-specific k-mers. New Phytol. 235, 801–809 (2022).

Han, Y. & Wessler, S. R. MITE-Hunter: a program for discovering miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements from genomic sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, e199 (2010).

Ellinghaus, D., Kurtz, S. & Willhoeft, U. LTRharvest, an efficient and flexible software for de novo detection of LTR retrotransposons. BMC Bioinformatics. 9, 18 (2008).

Steinbiss, S. et al. Fine-grained annotation and classification of de novo predicted LTR retrotransposons. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 7002–7013 (2009).

Gremme, G., Steinbiss, S. & Kurtz, S. GenomeTools: a comprehensive software library for efficient processing of structured genome annotations. IEEE/ACM Trans Comput Biol Bioinform. 10, 645–656 (2013).

Hubley, R., Smit, A. Repeat Modeler Open-1.0, http://www.repeatmasker.org (2008).

Tarailo-Graovac, M. & Chen, N. Using RepeatMasker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 25, 4.10.1–4.10.14 (2009).

Holt, C. & Yandell, M. MAKER2: an annotation pipeline and genome-database management tool for second-generation genome projects. BMC Bioinformatics. 12, 1–14 (2011).

Kim, D., Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods. 12, 357–360 (2015).

Pertea, M. et al. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat Biotechnol. 33, 290–295 (2015).

Liu, T. et al. Reannotation of the cultivated strawberry genome and establishment of a strawberry genome database. Hortic Res. 8, 41 (2021).

Gotoh, O. A space-efficient and accurate method for mapping and aligning cDNA sequences onto genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 2630–2638 (2008).

Brůna, T. et al. BRAKER2: automatic eukaryotic genome annotation with GeneMark-EP+ and AUGUSTUS supported by a protein database. NAR Genom Bioinform. 3, lqaa108 (2021).

Stanke, M. et al. Using native and syntenically mapped cDNA alignments to improve de novo gene finding. Bioinformatics. 24, 637–644 (2008).

Lomsadze, A. et al. Gene identification in novel eukaryotic genomes by self-training algorithm. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 6494–6506 (2005).

Shumate, A. & Salzberg, S. L. Liftoff: accurate mapping of gene annotations. Bioinformatics. 37, 1639–1643 (2021).

Buchfink, B., Xie, C. & Huson, D. H. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat Methods. 12, 59–60 (2015).

Quevillon, E. et al. InterProScan: protein domains identifier. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, W116–W120 (2005).

Huerta-Cepas, J. et al. Fast genome-wide functional annotation through orthology assignment by eggNOG-Mapper. Mol Biol Evol. 34, 2115–2122 (2017).

Chan, P. P. et al. tRNAscan-SE 2.0: improved detection and functional classification of transfer RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, 9077–9096 (2021).

Carver, T. J. et al. ACT: the Artemis comparison tool. Bioinformatics. 21, 3422–3423 (2005).

Kalvari, I. et al. Rfam 14: expanded coverage of metagenomic, viral and microRNA families. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D192–D200 (2021).

Nawrocki, E. P. & Eddy, S. R. Infernal 1.1: 100-fold faster RNA homology searches. Bioinformatics. 29, 2933–2935 (2013).

Li, H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 34, 3094–3100 (2018).

Goel, M. et al. SyRI: finding genomic rearrangements and local sequence differences from whole-genome assemblies. Genome Biol. 20, 277 (2019).

Goel, M. & Schneeberger, K. plotsr: visualizing structural similarities and rearrangements between multiple genomes. Bioinformatics. 38, 2922–2926 (2022).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR28576446 (2024).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR28576447 (2024).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR28576448 (2024).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR28576449 (2024).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR28576450 (2024).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR28576451 (2024).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR28576452 (2024).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR28576453 (2024).

NCBI GenBank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.gca:GCA_045269825.1 (2024).

NCBI GenBank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.gca:GCA_045516675.1 (2024).

NCBI GenBank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.gca:GCA_045516685.1 (2024).

NGDC Genome Warehouse https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gwh/Assembly/83959/show (2024).

Lu, J. Haplotype-resolved chromosome-level genome assembly of Fragaria × ananassa Duch. cv. ‘Yuexin’. Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28675166.v3 (2025).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 26, 589–595 (2010).

Ou, S. & Jiang, N. LTR_retriever: A Highly Accurate and Sensitive Program for Identification of Long Terminal Repeat Retrotransposons. Plant Physiol. 176, 1410–1422 (2018).

Rhie, A. et al. Merqury: reference-free quality, completeness, and phasing assessment for genome assemblies. Genome Biol. 21, 245 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U23A20215), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (nos. 226-2024-00063) and the 111 project (B17039).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wenbo Chen and Kunsong Chen conceived the study. Xiaofang Yang raises the plants. Huazhao Yuan provided the ‘Camarosa’ leaves. Jiao Lu and Longwen Makun processed the samples and extracted the genomic DNA and RNA. Jiao Lu processed genome assemble, annotation and all the data analysis. Wenbo Chen and Jiao Lu wrote the manuscript. Wenbo Chen, Kunsong Chen, and Donald Grierson revised the manuscripts.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, J., Makun, L., Yang, X. et al. Haplotype-resolved chromosome-level genome assembly of Fragaria × ananassa Duch. cv. ‘Yuexin’. Sci Data 12, 974 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05322-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05322-z