Abstract

The scaled utilization of cultivated land has enhanced agricultural development and productivity. Quantifying its spatial distribution is essential for optimizing agricultural decision-making. Xinjiang, a vital grain production region in China, holds paramount study significance due to its distinct geographical location and fragile natural environment. However, most studies on cultivated land fragmentation rely on outdated raster datasets. In this study, we introduce a cultivated land dataset of Xinjiang in a vector form with higher boundary accuracy, and more suitable for cultivated land statistics. A novel parcel extraction method that integrates the Swin Transformer for multi-scale semantic information and DiffusionEdge for capturing fine boundary details is proposed, which enhances the accuracy of land parcel extraction from 10-meter resolution Sentinel-2 imagery, obtained from the Copernicus Open Access Hub. Finally, we present a practical and up-to-date vector dataset of cultivated land. The Technical Validation analysis substantiates the reliability and applicability of the dataset. Through this study, we contribute to developing a replicable methodology for robust cultivated land extraction and parcel-wise cultivated land analysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

The large-scale utilization of cultivated land offers numerous advantages. It enables unified planning and layout of agricultural production, significantly improving labor productivity1 and facilitating the rapid adoption of new technologies and crop varieties2. However, owing to the rapid advancement of urbanization and industrialization, as well as the adjustment of ecological construction and agricultural cropping patterns, the large-scale utilization of cultivated land has been impeded3. A large amount of high-quality arable land has been converted to non-agricultural uses, resulting in a reduction and fragmentation of arable land resources4. This more fragmented and isolated fragmentation pattern negatively impacts production efficiency, technological efficiency, and scale efficiency5,6. Therefore, accurately assessing the degree of scale utilization and fragmentation of cultivated land is crucial for maintaining the stability of cultivated land area and formulating optimized utilization patterns of cultivated land7.

Xinjiang is one of the key agricultural production bases in China8,9, particularly in producing grains, cotton, fruits, and vegetables. Therefore, studying the fragmentation of arable land in Xinjiang is of significant practical importance. The quality10 and expansion patterns11 of farmland in Xinjiang have become focal points of academic research. At the same time, management measures such as agricultural land transfer12,13, and land restoration14 are also being actively explored. With the continuous advancement of Earth observation technologies, remote sensing has become a key tool for global land resource investigation and monitoring due to its wide coverage and relatively low cost15,16. Research on changes in cultivated land in Xinjiang, based on remote sensing technologies and related products, has achieved numerous results. However, most of the research data currently focus on periods up to 2020 or earlier17,18,19, and often rely on low-resolution remote sensing data19,20,21. Moreover, specialized studies on the fragmentation and scaling characteristics of cultivated land in Xinjiang remain relatively scarce. Therefore, conducting in-depth investigations into the fragmentation and scale characteristics of cultivated land in Xinjiang is particularly crucial, especially using the latest high-resolution remote sensing data for analysis.

This study uses Sentinel-2 remote sensing imagery with a resolution of 10 m in 2019 and 2023 and a cultivation land extraction algorithm to generate a vector data set at the parcel level in Xinjiang22. This dataset is used to assess the region’s fragmentation and scale characteristics of cultivated land. The findings will provide a scientific basis for optimizing land resource allocation and enhancing agricultural productivity, thereby supporting decision-making that balances cultivated land use and ecological conservation within the region. The results of this study are of significant importance for promoting sustainable agricultural development in Xinjiang.

Methods

Study area

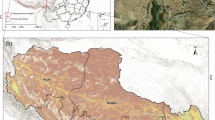

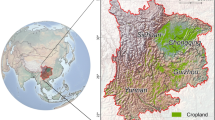

Xinjiang is located in the arid and semi-arid region of northwest China. Its vast territory covers approximately 1.66 million square kilometers, accounting for about one-sixth of China’s total land area23. Its unique geographical location and natural environment make it highly representative and distinctive for research on cultivated land.

On the one hand, Xinjiang is characterized by the Tianshan, Altai, and Kunlun mountain ranges, as well as the Tarim and Junggar basins, forming a unique geomorphological pattern of “three mountains and two basins” (as shown in Fig. 1)24. The Tianshan Mountain range divided the regions into northern and southern parts, and the resulting topographical differences led to significant variations in the natural environment and cultivated land distribution between northern and southern Xinjiang25. Northern Xinjiang has relatively abundant water resources, with higher precipitation and an average annual temperature of 8.5 °C, receiving 222.9 mm of precipitation. This area primarily cultivates crops like wheat, corn, and sugar beet, with a high degree of agricultural mechanization and farmland centralization. In contrast, southern Xinjiang is more arid, with an average annual temperature of 13.4 °C and only 88.6 mm of annual precipitation26. Southern Xinjiang agriculture relies heavily on irrigation systems, with farmland mainly concentrated in oasis areas and is dominated by cotton cultivation27. The characteristics of farmland distribution in northern and southern Xinjiang reflect regional differences in water resources and climate conditions, highlighting the distinct agricultural management needs between the two areas. Given Xinjiang’s complex geographical and climatic conditions, the fragmentation and scale of cultivated land have become key factors influencing farm productivity and sustainable development.

On the other hand, it is located in arid and semi-arid zones with a relatively fragile ecosystem28. Accelerating urbanization29, industrialization30, ecological construction31, and the adjustment of agricultural planting structures32 put even more pressure on the reduction and fragmentation of cultivated land resources. The changes in cultivated land, driven by the intertwined effects of natural and human factors, provide valuable samples for exploring cultivated land fragmentation and its scaled utilization.

Data sources

-

Xinjiang Administrative Boundary Data and Military Grid Reference System (MGRS)

Xinjiang Administrative Boundary Data refers to geographic information that delineates the spatial extent of administrative divisions at various levels within the Xinjiang region, typically provided as polygon features33. In this study, the data were obtained from the National Catalog Service for Geographic Information (http://www.webmap.cn), based on the latest administrative division standards. These data provide an authoritative spatial reference framework for defining the study area and ensuring consistency in subsequent geospatial operations.

To facilitate seamless coverage and systematic processing of Sentinel-2 imagery, we further adopted a global grid system based on the Military Grid Reference System (MGRS), which divides the Earth’s surface using a UTM-based scheme34,35. A total of 237 MGRS tiles were selected to cover the entire Xinjiang region (as shown in Fig. 1), aligning precisely with the administrative boundaries. The MGRS grid data were downloaded from the official MGRS Data website (https://mgrs-data.org). This grid-based partitioning enabled systematic tiling of the study area, enhancing spatial organization and ensuring consistency in geolocation, which mosaicking of remote sensing imagery.

-

Sentinel-2 imagery

The primary dataset utilized in this study is the Sentinel-2 optical remote sensing imagery provided by the European Space Agency (ESA) via the Copernicus Open Access Hub (https://dataspace.copernicus.eu). The Sentinel-2 mission consists of two structurally identical satellites, Sentinel-2A and Sentinel-2B. They operate on the same sun-synchronous orbit, but with a phase difference of 180°, enabling complementary observations. This dual-satellite configuration reduces the revisit cycle for the equatorial region from 10 days with a single satellite to 5 days, significantly enhancing the temporal and spatial resolution36. Each satellite is equipped with a MultiSpectral Instrument (MSI) capable of capturing imagery across 13 spectral bands, covering the visible, near-infrared (VNIR), and shortwave infrared (SWIR) regions of the electromagnetic spectrum. These include four bands at 10-meter spatial resolution (B2–B4 in the visible range and B8 in the near-infrared), six bands at 20-meter resolution (B5–B7, B8a, B11, B12), and three atmospheric correction bands at 60-meter resolution37. In this study, we primarily employed the 10-meter resolution bands, which strike a favorable balance between spatial detail and spectral sensitivity. By focusing on these high-resolution bands, we ensured the preservation of fine-scale spatial structures while maintaining sufficient spectral information to support accurate delineation of cultivated land boundaries, particularly in heterogeneous agricultural landscapes typical of the Xinjiang region.

To ensure exhaustive spatial coverage of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, we selected a total of 237 Military Grid Reference System (MGRS) tiles, fully encompassing the diverse agro-ecological zones across the region without spatial discontinuities (as shown in Fig. 1). Regarding temporal coverage, the imagery was acquired from the growing seasons of 2019 and 2023, with a specific focus on the summer months (July and August) of each year. These months represent the peak phenological stage of most crops in Xinjiang, characterized by dense vegetative cover and strong spectral separability from other land cover types, which may enhance the accuracy of cultivated land boundary delineation. Table 1 shows the main information and sources of all data used in this study.

Technical solutions

The overall framework is divided into four main steps (Fig. 2): (1) Obtain Sentinel-2 imagery of the study area. (2) Sentinel-2 imagery pre-processing. It is applied to guarantee the quality of the remote sensing image. (3) Train models and build the parcel-level vector dataset in Xinjiang. (4) Apply the parcel-level vector dataset22.

Definition of a parcel

This study defines a parcel as the smallest land unit with homogeneous attributes and distinct boundaries, typically separated by natural or man-made features such as field ditches and roads. From an image analysis perspective, parcels in large-scale farmland typically have regular shapes and simple geometric structures, while fragmented farmland often consists of smaller land units or complex obstacles. To accurately delineate these parcels, we used Sentinel-2 imagery with a 10 m resolution to identify parcel boundaries and features.

During the labeling process of samples, it is necessary to ensure the semantic integrity and boundary details of the cultivated land parcels of the sample. Therefore, as shown in Fig. 3, straight lines should be used to draw the outlines of the cultivated land parcels as precisely as possible. Two lines are required to accurately represent rigid boundaries (e.g., field ridges separating different parcels). In contrast, a single line suffices for soft boundaries (e.g., internal field ridges within a single parcel). This approach ensures that the parcels’ semantic and boundary details are effectively captured.

Sentinel-2 imagery and pre-processing

The pre-processing workflow of Sentinel-2 remote sensing data covers several key steps to ensure a high-quality generated image. Through steps such as:

Firstly, with the MGRS grid, the Sentinel-2 image data within the corresponding range are collected from the Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem (https://dataspace.coperni-cus.eu). We select the data for the summer period. The reason is that crops grow vigorously in summer, which enables more precise identification of parcel features. Meanwhile, to reduce the impact of cloud cover on remote sensing observations, images with a cloud cover threshold of no more than 30% were selected as the baseline during the data filtering process. In this manner, the impact of cloud interference on observations can be effectively mitigated, ensuring high-quality data and providing a robust foundation for subsequent research.

Secondly, the Sen2Cor v238,39 software is used for radiometric calibration and atmospheric correction. Next, band synthesis operations are performed on the four bands, each with a resolution of 10 meters, to create panchromatic image data. Subsequently, cloud masking is applied to the images. The Scene Classification Layer (SCL) single-band mask classification file in Sentinel-2 removes pixels in invalid areas, such as clouds and cloud shadows. Then, the data from each location are stacked chronologically, with earlier data given higher priority. If any invalid areas are found, they are filled with later data, and this process continues until a complete image without any invalid regions is obtained. Subsequently, PCI Geomatica 201840 is employed for image mosaicking and stitching. This process seamlessly combines multiple images into one complete image that covers the entire research area, removing inconsistencies in the overlapping regions and generating continuous surface observation data. The mosaicked imagery (in Fig. 4), with a spatial resolution of 10 meters and enhanced spectral consistency, clearly represents the distribution and morphology of cultivated land within the study area. The large volume of the imagery, occupying approximately 380 GB of storage space, reflects the substantial data size resulting from its high resolution and rich information content. Finally, to reduce storage space and improve computational efficiency, the pixel depth of the imagery was converted from 16-bit to 8-bit to meet the requirements for subsequent analysis and processing.

Train models and build the parcel-level vector dataset in Xinjiang

The third step involves training the model and building the Xinjiang dataset. This step is divided into four sub-steps: (1) Building the sample set: The sample set is constructed by selecting representative samples annotated in parcel form. (2) Model training: The Swin Transformer and DiffusionEdge models are independently trained to obtain their respective weights. The algorithm’s details will be introduced in the following subsection. (3) Vectorization and technical validation: The trained models are used for information fusion and vectorization on the test set. After vectorization, technical validation is conducted to assess the results. Based on the feedback from this validation, the models are further optimized to improve performance. (4) Building the parcel-level vector dataset in Xinjiang22: Once the vectorization results of the test set meet the predefined criteria, the semantic and boundary information of each cultivated land parcel within Xinjiang will be extracted and vectorized, and finally, the parcel-level vector dataset will be constructed.

Algorithm details

This study proposes a cultivated land parcel extraction approach based on semantic and boundary information integration. Semantic information is derived through semantic segmentation, and boundary information is obtained through boundary detection. Then, the semantic and boundary information are combined to acquire concise and closely adhering polygonal vectors of parcels.

Semantic segmentation and boundary detection are critical steps in generating semantic and boundary information for the parcels. To this end, the Swin Transformer41 and DiffusionEdg42 models are implemented.

Semantic information is processed using the Swin Transformer. The Swin Transformer was chosen due to its superior performance in remote sensing image segmentation tasks43. Its hierarchical structure enables feature extraction at multiple scales44, making it suitable for capturing complex, large-scale parcel features. Additionally, Swin’s local attention mechanism captures rich details within parcels, effectively enhancing boundary clarity and texture coherence across regions. Specifically, image patches are progressively fed into the network, where the local attention module of the network effectively captures detailed features of the cultivated land regions in the imagery, while its hierarchical structure preserves global contextual semantic information. Ultimately, the semantic segmentation results of the farmland regions are obtained.

After obtaining semantic information, DiffusionEdge is used for boundary detection. The DiffusionEdge model employs an autoencoder to encode the input image into the latent space. Subsequently, the model adopted a decoupled diffusion model to perform iterative denoising operations in the latent space. During this process, the denoising U-Net collaborates with the adaptive Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) filter to adjust the features, thereby highlighting the edge information. Finally, the denoised latent code is decoded into an edge map in the image space. Compared to traditional deep learning-based boundary detection methods, DiffusionEdge has provided higher precision in boundary extraction. It distinguishes boundaries between different parcels, resulting in finer and more precise boundary maps42. This method requires minimal post-processing to accurately extract fine boundaries, thereby significantly streamlining the subsequent parcel extraction process.

During the training phase, we fine-tuned the Swin Transformer and DiffusionEdge models using manually annotated samples based on preprocessed 10-meter resolution Sentinel-2 imagery from 2019 and 2023. The cultivated land samples were manually labeled in this study and are not derived from any publicly available datasets. To ensure the representativeness of the training data, samples were selected from diverse agricultural regions across Xinjiang, covering a wide range of geographic locations and farming practices (as illustrated in Fig. 7). This fine-tuning approach, informed by previous empirical studies45, not only accelerated the training process but also significantly enhanced the models’ performance in extracting features of cultivated land parcels.

During the prediction phase, we employed a “border-ignored prediction” sliding window46 strategy to address the issues of insufficient boundary information and mosaic artifacts at image stitching seams. In the prediction process, the sliding window method ignores the boundary regions and stitches together only the valid areas of the predictions, thereby ensuring smoother transitions at image edges, reducing blurriness at tile boundaries, and ultimately improving the accuracy of parcel extraction.

The key parameters significantly affecting model performance and computational efficiency are the window size and the size of the valid area46. The window size was set according to the model’s input-output dimensions (512 × 512 pixels) to maximize model performance. The valid area size was determined through simple comparative experiments. To evaluate the impact of the algorithm on model performance, we randomly selected 26 sample images with a resolution of 1024 × 1024 pixels for the experiments, using the Swin model as the network. Intersection over union (IOU), overall accuracy (OA), and F1 score (Eqs. 6, 7, and 8) were adopted as performance evaluation metrics47, while Frames Per Second (FPS) was used as the speed evaluation metric48. Let N denote the number of images processed during inference and T the total inference time (in seconds, s); the FPS can then be calculated as follows:

The relevant experimental results are shown in Table 2. According to the results, when the valid area size is set to 384 × 384 pixels, the model achieves high accuracy (with superior IOU, OA, and F1 scores) while also maintaining an ideal inference speed. It is worth noting that a smaller FPS value indicates slower inference speed; therefore, an appropriate balance between accuracy and efficiency was achieved under this configuration.

Next, we fuse the semantic and boundary information of the cultivated land parcels. First, a non-maximum suppression (NMS) operation is applied to refine the boundary results49. Although the DiffusionEdge model can extract relatively fine and accurate boundaries, in some cases the output boundaries may exceed one pixel in width. This can lead the subsequent 8-neighborhood search to fall into local optima, hindering the achievement of a globally optimal solution. Moreover, further refinement of the boundaries helps to clearly delineate the boundaries between land parcels, thereby facilitating effective integration with the semantic information.

In the process of fusing semantic and boundary information, we adopt a conditional probability modeling approach. The underlying assumption of this method is that boundaries typically occur where there is an abrupt change in semantic information, indicating a strong correlation between boundary information and semantic distribution. Based on this idea, we model the probability of boundary occurrence conditioned on the known semantic segmentation results, thereby establishing a mechanism in which semantic information provides both constraints and supplementary support for boundary prediction.

Specifically, let S represent the semantic segmentation results generated by the Swin Transformer, D denote the boundary results extracted by DiffusionEdge, and GT(E) represent the ground truth annotations of the boundaries. The objective is to maximize the similarity between the predicted boundaries and the ground truth boundaries, given the semantic segmentation results, i.e.:

The above formula indicates that, given the semantic segmentation result S, the goal is to maximize the similarity between the fused boundary result P(D|S) and the ground truth boundary GT(E). This modeling approach transforms the challenging task of directly extracting accurate boundary information from remote sensing imagery into a conditional probability problem of inferring boundaries based on semantic regions. Through this fusion process, semantic and boundary information are effectively integrated in a complementary and unified manner.

Finally, we obtain the vectorization results based on the fused boundary information. The specific implementation steps are as follows: First, the boundary pixels obtained through information fusion are traversed, and based on the number of boundary pixels within an 8-neighborhood, they are classified into three categories: (1) breakpoints: where the 8-neighborhood contains only one boundary pixel; (2) connection points: where the 8-neighborhood contains two boundary pixels; and (3) key points: where the 8-neighborhood contains three or more boundary pixels. Breakpoints are removed, leaving only the connection and key points. Then, starting from the key points, the boundary paths are tracked following the 8-neighborhood search rules until another key point or a path endpoint is reached, thereby completing the identification of boundary paths for the land parcels. Based on the extracted nodes and edges, a graph model of the land parcel boundaries is constructed, and the minimum closed paths are extracted from the model to generate closed polygon vector results, thereby achieving a precise representation of the spatial characteristics of the land parcels.

Building the dataset

To construct the vector dataset of cultivated land in Xinjiang, a systematic pre-processing workflow was first applied to Sentinel-2 remote sensing imagery. This included radiometric calibration, atmospheric correction, band synthesis, cloud removal, and image mosaicking, ensuring radiometric consistency and spatial continuity across the input imagery. These steps laid a high-quality data foundation for subsequent cultivated land extraction.

Subsequently, training samples were extensively selected based on the diverse agro-ecological zones of Xinjiang. An iterative optimization strategy was adopted to train the models, aiming to enhance its generalization capability for cultivated land extraction. Once the vectorization results on an independent test set reached the predefined accuracy threshold, the models were deployed for large-scale extraction across the entire Xinjiang region.

During the feature extraction stage, the trained Swin Transformer model was used to obtain semantic segmentation results for pixel-level classification of cultivated land. Simultaneously, the DiffusionEdge model was employed to extract high-precision field boundaries. Although DiffusionEdge effectively delineates field contours, in some regions the boundary width may exceed one pixel. To improve boundary sharpness and facilitate effective integration with semantic features, a non-maximum suppression algorithm was introduced for boundary refinement49.

To integrate semantic and boundary information, this study employed a conditional probability-based fusion method. Under the condition of known semantic segmentation, the method estimates the likelihood of boundary occurrence, thereby enabling semantic constraints and supplementing the boundary results. Subsequently, polygon vectorization was applied to the fused results, generating individual cultivated land parcel vectors characterized by spatial closure and semantic consistency.

After vectorization, the dataset underwent a series of systematic post-processing and quality control procedures using ArcGIS 10.2 to ensure spatial accuracy and attribute consistency. These procedures included: (1) Geometric validation: ArcGIS tools were employed to verify the integrity and validity of vector geometries, ensuring that all parcels are free from self-intersections, duplicate vertices, empty geometries, and other topological anomalies50; (2) Area calculation: To facilitate subsequent spatial analysis, parcel areas were computed based on a consistent map projection. The final vector dataset was projected using the Albers Equal-Area Conic Projection51, with parameters defined as follows: central meridian at 85°E, standard parallels at 35°N and 45°N, and the China Geodetic Coordinate System 2000 (CGCS2000) as the reference coordinate system; (3) Small fragment removal: Parcels smaller than 0.4 hectares were excluded, as such fragments are typically attributed to model misclassification or boundary over-refinement during vectorization; (4) Attribute consistency checks: A detailed review was conducted to ensure that all attribute fields, such as parcel identifiers and area values, were complete and consistent in all data.

Finally, all vector data were organized into a standardized structure by year, forming the Xinjiang cultivated land vector dataset22, which is now publicly available to support applications in regional agricultural research, policy development, and resource management.

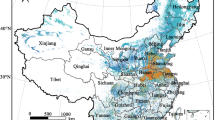

Data Records

The dataset is available at Figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28210715)22. It presents the first publicly released cultivated land vector dataset based on 10 m resolution imagery for the Xinjiang region in 2019 and 2023. The data is provided in Shapefile (SHP) format, with a spatial reference system based on the CGCS2000 coordinate system. It can be loaded into GIS software, such as ArcGIS and QGIS52, for data visualization and spatial analysis. Figure 5 illustrates the spatial distribution of the cultivated land dataset constructed in this study across the entire Xinjiang region, highlighting the coverage characteristics and overall distribution patterns of cultivated land in different geographical areas.

Covering the entire Xinjiang region, the dataset22 includes over 670,000 cultivated land parcels for 2019 and over 690,000 parcels for 2023. Compared to existing raster-based datasets, this vector dataset offers more precise parcel boundaries and maintains accurate topological relationships. As a result, it provides a more detailed and reliable representation of the spatial distribution and structural characteristics of cultivated land in the region. To better demonstrate this advantage, we have specifically zoomed in on the results from four local areas, as shown in Fig. 6.

(a) Sample located in southern Xinjiang, with a longitude of 81° 12′ 15.49′′ E and a latitude of 40° 39′29.48′′ N; (b) Sample located in southern Xinjiang, with a longitude of 80° 18′ 57.96′′ E and a latitude of 40° 27′ 19.80′′ N; (c) Sample located in northern Xinjiang, with a longitude of 84° 31′ 37.20′′ E and a latitude of 44° 25′ 46.20′′ N; (d) sample located in northern Xinjiang, with a longitude of 85° 50′ 31.92′′ E and a latitude of 44° 30′ 30.23′′ N.

This dataset22 provides a robust foundation for analyzing the fragmentation and scale of cultivated land in Xinjiang. In addition, it can be utilized to formulate agricultural strategies, optimize irrigation and fertilization, and provide support for land use planning and decision-making. Furthermore, it can offer guidance for determining the direction of cultivated land consolidation and optimization, thereby supporting the transformation and upgrading of agricultural production structures.

Technical Validation

Assessing the accuracy of the dataset22 is a crucial step in validating the reliability of its application in relevant fields. To ensure the effectiveness of the dataset, we employed three evaluation methods: pixel-level accuracy comparison, object-level accuracy comparison, and prediction bias analysis.

Firstly, the pixel-level accuracy comparison evaluates the classification accuracy at the individual pixel level. This involves calculating the classification results for each pixel and comparing the predicted outcomes with the ground truth labels. We use metrics such as precision, recall, F1 score, intersection over union (IoU), and overall accuracy (OA)53,54 to assess the model’s performance at the pixel level.

Secondly, the object-level accuracy comparison evaluates the spatial structure of the extracted results from a broader perspective. We utilize Global Over-Classification (GOC), Global Under-Classification (GUC), and Global Total-Classification (GTC)55 for this purpose. GOC measures over-segmentation, where a single ground truth parcel is incorrectly segmented into multiple predicted parcels. A higher GOC value indicates greater over-segmentation. GUC measures under-segmentation, merging multiple ground truth parcels into a single predicted parcel. A higher GUC value suggests greater under-segmentation. GTC combines both GOC and GUC to provide a comprehensive evaluation of global classification quality.

Finally, the prediction bias analysis evaluated the algorithm’s prediction performance56. By comparing biases in metrics such as the number of cultivated land parcels, total cultivated land area, and average parcel area, the reliability of the dataset was further validated.

Sample construction for training and testing

The quantity and distribution of samples are crucial in constructing training and testing datasets. This study includes 204 samples, including 180 positive and 24 negative samples, with each sample standardized to a size of 1024 × 1024 pixels. Among them, a large number of positive samples facilitates the model’s all-round and in-depth learning of the diverse characteristics of cultivated land, thus improving the accuracy of cultivated land identification. Meanwhile, an appropriate number of negative samples assist the model in quickly and accurately distinguishing between cultivated and non-cultivated land in the presence of complex geographical images, reducing misjudgments57.

For the construction of negative samples, we selected a variety of land cover types that are commonly confused with cultivated land in remote sensing classification, including forests, grasslands, barren land, water bodies, urban areas, and wetlands58. These negative samples were carefully selected from diverse geographic regions across Xinjiang to encompass a wide range of non-cultivated land types with spectral characteristics similar to cultivated land, thereby enhancing the model’s ability to distinguish non-cultivated areas. To mitigate potential class bias during training, several strategies were adopted to improve the fairness and robustness of the learning process. Specifically, we employed an iterative optimization approach to progressively incorporate representative negative samples during the training of the models59. Meanwhile, we maintained a balanced distribution of negative sample types, ensuring that each category contained at least three base samples. In addition, data augmentation techniques, including geometric transformations such as flipping and rotation, were applied to the negative samples to enhance sample diversity and mitigate the risk of overfitting, thereby improving the robustness of the model60.

Figure 7 shows the sample distribution, with points spread widely across different regions, particularly near key areas and characteristic points. This sampling strategy reflects the diversity of the data and aims to ensure that the model can be trained under variable environmental conditions, thereby improving its generalization ability. Regional differences have been thoroughly taken into account during the sample selection. Thus, 114 samples were chosen from northern Xinjiang, and 90 were selected from southern Xinjiang, demonstrating a prudent consideration of geographical and cultivated land characteristics.

To train the models, we adopted an iterative optimization strategy to gradually enrich the sample set and improve model performance. During training, the Adam optimizer was used, with an initial learning rate set to 5 × e−5, a batch size of 2, and 100 training epochs, while an early stopping strategy was applied to prevent overfitting. To further optimize the training process, we introduced a learning rate decay schedule, gradually reducing the learning rate as training progressed. To increase sample diversity and mitigate overfitting, a suite of data augmentation techniques—including geometric transformations such as horizontal flipping, vertical flipping, and random rotation—was applied60. Given the high cost and labor intensity of manual annotation, an overlapping cropping strategy with 20% overlap was employed to maximize the effective utilization of annotated regions and reduce labeling waste. All training patches were uniformly resized to 512 × 512 pixels to maintain consistency across the dataset.

To validate the effectiveness of the constructed dataset, we randomly selected 26 test samples (shown in Fig. 7), covering a total cultivated land area of 65,306.19 hectares and comprising 4,973 parcels. The sample size further demonstrates the diversity and representativeness of the selected samples, enabling comprehensive inference and validation of the dataset’s effectiveness.

Pixel-level accuracy comparison

In the pixel-level accuracy comparison, precision evaluation involves quantifying the intersected area corresponding to the True Positive (TP) pixel count. This is combined with the cumulative sum of TP, False Positive (FP), and False Negative (FN) pixels. Specifically, TP represents the pixels correctly identified as cultivated land, FP refers to those incorrectly classified as cultivated land, and FN indicates the misclassified non-cultivated land pixels. Five standard metrics are used for the evaluation: precision, recall, F1 score, intersection over union (IoU), and overall accuracy (OA)53,54. More specifically, precision reflects the false alarm rate, and recall reflects the false positive rate of the model.On the other hand, F1 considers both indices; therefore, a more significant score indicates a better model. IoU measures the overlap ratio between the detected class on the detection map and the ground truth, serving as a critical metric for evaluating spatial resolution accuracy. OA refers to the overall accuracy of pixel classification. It represents the proportion of correctly classified samples among all samples. The higher the OA value, the more accurate the classification results. The calculation methods for these five metrics are as follows:

The results are shown in Table 3. The table presents multi-dimensional evaluation metrics that reflect the performance of the model. Specifically, the precision is 91.40%, demonstrating that the model effectively minimizes false positives, thereby reducing the likelihood of misclassifying non-cultivated pixels as cultivated land. The recall rate for the test set is 97.26%, indicating that the model successfully identifies the most cultivated pixels. The F1 score reaching 94.17% signifies that the model has effectively balanced the two aspects, representing a superior overall performance. The IoU is 89.11%, reflecting the model’s high spatial accuracy in pixel recognition. In addition, the OA of 94.69% indicates the model’s overall classification accuracy at the pixel level, ensuring strong reliability in practical applications. However, we recognize that the model’s performance is, to some extent, limited by the intrinsic characteristics of remote sensing imagery in the Xinjiang region. Specifically, the 10-meter spatial resolution of Sentinel-2 imagery may be inadequate for reliably distinguishing between spectrally similar land cover types in certain areas, leading to the occurrence of mixed pixels—where a single pixel contains spectral information from multiple categories61. Furthermore, in parts of southern Xinjiang, cultivated land exhibits pronounced spatial heterogeneity, characterized by intercropping practices, sparse vegetation cover, and fragmented field patterns. Collectively, these factors introduce considerable challenges to achieving accurate pixel-level classification across the region, particularly in areas with indistinct boundaries or complex agricultural structures.

Object-level accuracy comparison

The object-level accuracy evaluation is designed to assess how well the predicted segments align with ground truth objects in terms of shape and spatial extent62. This evaluation relies on two fundamental types of segmentation errors: over-segmentation and under-segmentation55.

Let Si be a predicted object and Oi be its corresponding ground truth object with the maximum area of overlap. The areas of these objects are denoted by area(Si) and area(Oi), and their intersection is area(Si ∩ Oi). Based on these definitions, we compute the following error metrics:

Over-segmentation error (OC): Quantify the extent to which a true land parcel is erroneously segmented into multiple predicted parcels.

Under-segmentation error (UC): Quantifies the extent to which multiple true land parcels are erroneously merged into a single predicted parcel.

Total Classification Error (TC): Represents the overall error level by computing the root mean square of OC and UC.

To comprehensively assess the segmentation performance of the entire dataset, we compute the area-weighted averages of the three error metrics OC, UC, and TC resulting in the following three global evaluation indicators.

The results are shown in Table 4. The table demonstrates the model’s performance through three global metrics: GOC, GUC, and GTC. The analysis of these metrics indicates that the model performs exceptionally well in the cultivated land extraction task. Specifically, the GOC value of 0.12 indicates a minimal level of over-segmentation in the test set. The GUC value of 0.15 suggests that under-segmentation is rare throughout the dataset. In addition, the GTC value of 0.17 is relatively low. Overall, these results highlight the model’s ability to reduce over-segmentation and under-segmentation, achieving high classification accuracy and precise delineation of cultivated parcels. However, we acknowledge that certain types of errors still persist. For instance, over-segmentation may occur in irregularly shaped or elongated parcels, particularly when there is significant spectral heterogeneity within a single field. Conversely, under-segmentation is more likely to happen in adjacent fields that exhibit similar spectral features or where the boundary contrast is weak.

Prediction bias

In this study section, we evaluate the algorithm’s performance in predicting the total number and overall area of cultivated land parcels. To assess the precision of the predictive model, a comparison was made between the predicted results and the actual sample data. Table 5 presents three crucial indicators: quantity, total area, and mean cultivated land area. For each indicator, the specific values of both the sample results and the predicted results, along with the percentage variation between them, are enumerated in the table, and this percentage variation represents the prediction bias56.

The analysis reveals that the prediction model exhibited some bias in estimating the total area of cultivated land. Specifically, the predicted cultivated land area was 70.5 thousand hectares, while the actual sample area was 65.3 thousand hectares, resulting in a prediction bias of 7.79%. Regarding the mean area of the cultivated land, the predicted value was 14.05 hectares, compared to the actual sample value of 13.13 hectares, resulting in a prediction bias of 7.01%. Regarding the number of cultivated land parcels, the predicted value was 5,016 parcels. In comparison, the actual sample number was 4,973 parcels, resulting in a minor deviation of 0.8% between the predicted and sample results.

In general, the predicted results for the amount of cultivated land, the total area, and the mean area of cultivated land were slightly higher than the sample results, suggesting that the prediction model exhibited a relatively optimistic bias.

This relatively optimistic bias may stem from several factors. First, the spectral similarity between cultivated land and adjacent vegetation or field bunds can lead the model to misclassify marginal areas as cultivated land. This issue is further exacerbated by the mixed-pixel phenomenon, in which a single pixel captures signals from multiple land cover types, thereby reducing classification precision. Second, minor inaccuracies in the reference data, such as the underrepresentation of small or fragmented parcels, may also contribute to the discrepancy between the predicted and actual results. The overall deviation is relatively small; however, this bias may have implications for downstream applications that require precise area statistics, such as precision agriculture management or crop yield prediction63. The overestimation of cultivated land area may lead to slightly inflated estimates, which could affect the rational allocation of agricultural resources or the optimization of irrigation system decisions.

Usage Notes

This study provides a parcel-level cultivated land vector dataset22 for Xinjiang in 2019 and 2023, which can be used for various applications and research. Here, we provide a detailed overview of several application options.

Firstly, this dataset22 can be spatially integrated with a regular fishnet grid to quantitatively analyze the spatial distribution patterns and fragmentation characteristics of cultivated land across different regions64. By calculating the number of cultivated parcels or their average area within each grid cell, the granularity and spatial clustering of cultivated land can be revealed. To better illustrate the application of this method, ArcGIS 10.2 software was used to construct a 10 km × 10 km fishnet grid65 that covers the entire Xinjiang cultivated land vector dataset. The “Spatial Join” tool was then applied to extract the number of cultivated parcels and their average area within each grid cell. Subsequently, attribute filtering was used to remove invalid or noisy grid cells with very few cultivated land parcels. As shown in Fig. 8, the grid-based statistical results can be further transformed into heat maps or choropleth maps, intuitively displaying spatial differences in cultivated land structure. This method effectively highlights the distributional differences between southern and northern Xinjiang, as well as between oasis margins and core areas, helping to identify spatial hotspots and problem zones. This, in turn, provides effective spatial support for communicating research findings to non-specialist audiences, such as policymakers66.

Secondly, based on the cultivated land vector dataset22, a variety of spatial structural metrics—such as shape index, mean plot area, area-weighted mean shape index, and mean nearest neighbor distance—can be calculated to quantitatively characterize the fragmentation of cultivated land67,68. These indicators facilitate the assessment of spatial distribution patterns, land use efficiency, and the potential for land consolidation. For instance, small and irregularly shaped parcels often indicate a high degree of fragmentation, making them priority targets for land consolidation and reorganization. Through spatial analysis techniques, highly fragmented areas can be effectively identified, thereby providing spatial evidence to support land consolidation efforts and the promotion of appropriately scaled farming operations. Compared to raster data, vector datasets offer higher spatial precision and more accurate geometric representations, enabling more refined spatial analysis and visualization. This supports structural comparisons and planning decisions across multiple spatial scales.

In addition to the aforementioned research applications, this dataset is also well-suited for a wide range of spatial analysis tasks. However, it is important to note that its performance is still influenced by the inherent characteristics of remote sensing imagery. First, the 10-meter spatial resolution of Sentinel-2 imagery may lead to mixed-pixel issues in small-scale or geometrically complex areas, where a single pixel can capture spectral information from multiple land cover types, thus reducing the accuracy of parcel boundary delineation. Second, regional differences in the characteristics of cultivated land may further exacerbate this problem. Specifically, certain regions in southern Xinjiang are characterized by complex cropping patterns, and spectral similarities between cultivated land and surrounding non-cultivated land, all of which increase the uncertainty in image interpretation. Despite these limitations, the vector dataset demonstrates notable strengths in accurately capturing cultivated land boundaries, preserving parcel geometry, and maintaining topological relationships. It serves as a high-quality spatial data foundation for land resource monitoring, agricultural structure analysis, cultivated land fragmentation assessment, and policy-making, offering significant potential for research and practical applications.

Code availability

The code is publicly available: https://github.com/K-28X/data-production-code.

References

Li, H., Zhang, X., Zhang, X. & Wu, Y. Utilization benefit of cultivated land and land institution reforms: Economy, society and ecology. Habitat Int. 77, 64–70 (2018).

Ewert, F., Baatz, R. & Finger, R. Agroecology for a sustainable agriculture and food system: from local solutions to large-scale adoption. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 15, 351–381 (2023).

Wen-guang, C. & Xiang-bin, K. Science and Technology Innovation Strategy for Cultivated Land Conservation of China. Chinese Journal of Soil Science 54, 947–954 (2023).

Busko, M. & Szafranska, B. Analysis of changes in land use patterns pursuant to the conversion of agricultural land to non-agricultural use in the context of the sustainable development of the Malopolska Region. Sustainability 10, 136 (2018).

Latruffe, L. & Piet, L. Does land fragmentation affect farm performance? A case study from Brittany, France. Agric. Syst. 129, 68–80, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2014.05.005 (2014).

Manjunatha, A., Anik, A. R., Speelman, S. & Nuppenau, E. Impact of land fragmentation, farm size, land ownership and crop diversity on profit and efficiency of irrigated farms in India. Land Use Policy 31, 397–405, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2012.08.005 (2013).

Liu, Y. & Zhou, Y. Reflections on China’s food security and land use policy under rapid urbanization. Land use policy 109, 105699 (2021).

Tang, K. Agricultural adaptation to the environmental and social consequences of climate change in mixed farming systems: Evidence from North Xinjiang, China. Agric. Syst. 217, 103913 (2024).

Fang, Y., Wu, S., Hou, G. & Long, W. Spatiotemporal Changes and Driving Mechanisms of Cropland Reclamation and Abandonment in Xinjiang. Land 13, 1476 (2024).

Sheng, Y., Liu, W., Xu, H. & Gao, X. The spatial distribution characteristics of the cultivated land quality in the diluvial fan terrain of the arid region: a case study of Jimsar County, Xinjiang, China. Land 10, 896 (2021).

Cai, T. et al. The process-mode-driving force of cropland expansion in arid regions of China based on the land use remote sensing monitoring data. Remote. Sens. 13, 2949 (2021).

Wang, Y., Liu, G. & Liu, X. Spatiotemporal coupling and driving factors of farmland transfer and labor transfer based on big data: the case of Xinjiang, China. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2022, 7604448 (2022).

Yang, F. & Liu, G. Research on spillover effect of urbanization on rural land transfer based on the SDM model of intelligent computing. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2022, 9921309 (2022).

Liao, N., Gu, X., Wang, Y., Xu, H. & Fan, Z. Analysis of ecological and economic benefits of rural land integration in the manas river basin oasis. Land 10, 451 (2021).

Liu, J. et al. Spatiotemporal characteristics, patterns, and causes of land-use changes in China since the late 1980s. J. Geogr. sciences 24, 195–210 (2014).

Joshi, N. et al. A review of the application of optical and radar remote sensing data fusion to land use mapping and monitoring. Remote. Sens. 8, 70 (2016).

Wang, X. Changes in cultivated land loss and landscape fragmentation in China from 2000 to 2020. Land 11, 684 (2022).

Hao, W. et al. The impact of farmland fragmentation in China on agricultural productivity. J. Clean. Prod. 425, 138962 (2023).

Zhang, L. et al. Effects of farmland landscape fragmentation on agricultural irrigation in hotan oasis. Agriculture 12, 1503 (2022).

Wang, C. et al. Evaluation of spatial conflicts of land use and its driving factors in arid and semiarid regions: A case study of Xinjiang. China. Ecol. Indic. 166, 112483 (2024).

Cheng, Y. et al. Assessment and Prediction of Landscape Ecological Risk from Land Use Change in Xinjiang, China. Land 12, 895 (2023).

Wu, W. et al. Parcel-level vector data for scaled land utilization analysis in Xinjiang based on remote sensing image. Figshare, https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28210715 (2025).

Han, C., Zheng, J., Guan, J., Yu, D. & Lu, B. Evaluating and simulating resource and environmental carrying capacity in arid and semiarid regions: A case study of Xinjiang, China. J. Clean. Prod. 338, 130646 (2022).

Yao, J. et al. Recent climate and hydrological changes in a mountain–basin system in Xinjiang, China. Earth-Science Rev. 226, 103957 (2022).

Hu, Q., Zhao, Y., Huang, A., Ma, P. & Ming, J. Moisture transport and sources of the extreme precipitation over northern and southern Xinjiang in the summer half-year during 1979–2018. Front. Earth Sci. 9, 770877 (2021).

Mi, Q., Li, X. & Gao, J. How to improve the welfare of smallholders through agricultural production outsourcing: Evidence from cotton farmers in Xinjiang, Northwest China. J. cleaner production 256, 120636 (2020).

Zhu, Y., Sun, L., Luo, Q., Chen, H. & Yang, Y. Spatial optimization of cotton cultivation in Xinjiang: A climate change perspective. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinformation 124, 103523 (2023).

Yao, J., Zhao, Y., Chen, Y., Yu, X. & Zhang, R. Multi-scale assessments of droughts: A case study in Xinjiang,. China. Sci. Total. Environ. 630, 444–452 (2018).

Kang, L. & Xia, S. Study on Urbanization Sustainability of Xinjiang in China: Connotation, Indicators and Measurement. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 20, 2535 (2023).

Wang, J. & Zhu, X. Study on Development Relations of Xinjiang Industrialization and Urbanization-Under the Background of “The Belt and Road” Strategy. In 2016 International Conference on Economy, Management and Education Technology, 1013–1020 (Atlantis Press, 2016).

Cao, C., Luo, Y., Xu, L., Xi, Y. & Zhou, Y. Construction of ecological security pattern based on InVEST-Conefor-MCRM: A case study of Xinjiang. China. Ecol. Indic. 159, 111647 (2024).

Hai, Y. et al. Evaluating agricultural water-use efficiency based on water footprint of crop values: a case study in Xinjiang of China. J. Arid Land 12, 580–593 (2020).

Chang, Y. et al. Spatial pattern analysis of xinjiang tourism resources based on electronic map points of interest. Int. J.Environ. Res. Public Heal. 19, 7666 (2022).

Bauer-Marschallinger, B. & Falkner, K. Wasting petabytes: A survey of the Sentinel-2 UTM tiling grid and its spatial overhead. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote. Sens. 202, 682–690 (2023).

von Specht, S. & Ziebarth, M. J. The Data-Optimized Oblique Mercator Projection. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote. Sens. (2025).

Belgiu, M. & Csillik, O. Sentinel-2 cropland mapping using pixel-based and object-based time-weighted dynamic time warping analysis. Remote. sensing environment 204, 509–523 (2018).

Chaves, M. E. D., Picoli, M. C. A. & Sanches, I. D. Recent applications of Landsat 8/OLI and Sentinel-2/MSI for land use and land cover mapping: A systematic review. Remote. Sens. 12, 3062 (2020).

Louis, J. et al. Sentinel-2 Sen2Cor: L2A processor for users. In Proceedings living planet symposium 2016, 1–8 (Spacebooks Online, 2016).

Müller-Wilm, U., Devignot, O. & Pessiot, L. S2 MPC Sen2Cor configuration and user manual (2017).

Puliti, S. et al. Modelling above-ground biomass stock over Norway using national forest inventory data with ArcticDEM and Sentinel-2 data. Remote. Sens. Environ. 236, 111501 (2020).

Liu, Z. et al. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 10012–10022 (2021).

Ye, Y., Xu, K., Huang, Y., Yi, R. & Cai, Z. DiffusionEdge: Diffusion Probabilistic Model for Crisp Edge Detection. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, vol. 38, 6675–6683 (2024).

Xu, Z., Zhang, W., Zhang, T., Yang, Z. & Li, J. Efficient transformer for remote sensing image segmentation. Remote. Sens. 13, 3585 (2021).

Yuan, W. & Xu, W. MSST-Net: A multi-scale adaptive network for building extraction from remote sensing images based on swin transformer. Remote. Sens. 13, 4743 (2021).

Wang, D., Zhang, J., Du, B., Xia, G.-S. & Tao, D. An empirical study of remote sensing pretraining. IEEE Transactions on Geosci. Remote. Sens. 61, 1–20 (2022).

Wang, Z., Zhou, Y., Wang, S., Wang, F. & Xu, Z. House building extraction from high resolution remote sensing image based on IEU-Net. J. Remote. Sens 25, 2245–2254 (2021).

Liu, B., Wang, W., Wu, Y. & Gao, X. Attention Swin Transformer UNet for Landslide Segmentation in Remotely Sensed Images. Remote. Sens. 16, 4464 (2024).

He, X. et al. Swin transformer embedding UNet for remote sensing image semantic segmentation. IEEE transactions on geoscience remote sensing 60, 1–15 (2022).

Sun, C. & Vallotton, P. Fast linear feature detection using multiple directional non-maximum suppression. J. Microsc. 234, 147–157 (2009).

Wadembere, I. et al. Validation of GIS vector data during geo-spatial alignment. Int. J. Geoinformatics, (2014).

Yildirim, F., Kadi, F. & Kurtipek, A. Determination of an appropriate projection system for forest areas in Turkey. Geod. cartography 46, 41–47 (2020).

Khan, S. & Mohiuddin, K. Evaluating the parameters of ArcGIS and QGIS for GIS Applications. Int. J. Adv. Res. Sci. Eng 7, 582–594 (2018).

Liu, Z., Li, N., Wang, L., Zhu, J. & Qin, F. A multi-angle comprehensive solution based on deep learning to extract cultivated land information from high-resolution remote sensing images. Ecol. indicators 141, 108961 (2022).

Xu, L. et al. Delineation of cultivated land parcels based on deep convolutional networks and geographical thematic scene division of remotely sensed images. Comput. Electron. Agric. 192, 106611 (2022).

Li, M., Long, J., Stein, A. & Wang, X. Using a semantic edge-aware multi-task neural network to delineate agricultural parcels from remote sensing images. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote. Sens. 200, 24–40 (2023).

Mavrogiorgos, K., Kiourtis, A., Mavrogiorgou, A., Menychtas, A. & Kyriazis, D. Bias in Machine Learning: A Literature Review. Appl. Sci. 14, 8860 (2024).

Johnson, J. M. & Khoshgoftaar, T. M. Survey on deep learning with class imbalance. J. big data 6, 1–54 (2019).

Anderson, J. R. A land use and land cover classification system for use with remote sensor data, vol. 964 (US Government Printing Office, 1976).

Sung, K.-K. Learning and example selection for object and pattern detection. AI Technical Report AITR-1572, MIT libraries (1996).

Shorten, C. & Khoshgoftaar, T. M. A survey on image data augmentation for deep learning. J. big data 6, 1–48 (2019).

Hsieh, P.-F., Lee, L. C. & Chen, N.-Y. Effect of spatial resolution on classification errors of pure and mixed pixels in remote sensing. IEEE Transactions on Geosci. Remote. Sens. 39, 2657–2663 (2001).

Persello, C. & Bruzzone, L. A novel protocol for accuracy assessment in classification of very high resolution images. IEEE transactions on geoscience remote sensing 48, 1232–1244 (2009).

Sishodia, R. P., Ray, R. L. & Singh, S. K. Applications of remote sensing in precision agriculture: A review. Remote. sensing 12, 3136 (2020).

Zhao, Y. & Feng, Q. Identifying spatial and temporal dynamics and driving factors of cultivated land fragmentation in Shaanxi province. Agric. Syst. 217, 103948 (2024).

Xiao, Y., Huang, M., Xie, G. & Zhen, L. Evaluating the impacts of land use change on ecosystem service values under multiple scenarios in the Hunshandake region of China. Sci. Total. Environ. 850, 158067 (2022).

Attah, R. U., Gil-Ozoudeh, I., Garba, B. & Iwuanyanwu, O. Leveraging geographic information systems and data analytics for enhanced public sector decision-making and urban planning. Magna Sci Adv Res Rev 12, 152–63 (2024).

Wang, X. et al. Spatial-temporal characteristics of cropland distribution and its landscape fragmentation in China. Farming Syst. 2, 100078 (2024).

Hou, X., Liu, J., Zhang, D., Zhao, M. & Yin, Y. Effect of landscape-scale farmland fragmentation on the ecological efficiency of farmland use: a case study of the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 26935–26947 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Third Xinjiang Scientific Expedition Program (Grant No. 2021xjkk1300).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wei Wu, Liao Yang and Shuangyan Huang conceived the experiments, Yikai Zhao, You Zeng, Rui Liu, and Weisheng Wang conducted the experiments, Xiande Wu and Yikai Zhao analyzed the results and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, W., Zhao, Y., Yang, L. et al. Parcel-level vector data for scaled land utilization analysis in Xinjiang based on remote sensing image. Sci Data 12, 1010 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05359-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05359-0